ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mandates disclosure of large-scale adverse events to patients, even if risk of harm is not clearly present. Concerns about past disclosures warranted further examination of the impact of this policy.

OBJECTIVE

Through a collaborative partnership between VA leaders, policymakers, researchers and stakeholders, the objective was to empirically identify critical aspects of disclosure processes as a first step towards improving future disclosures.

DESIGN

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants at nine VA facilities where recent disclosures took place.

PARTICIPANTS

Ninety-seven stakeholders participated in the interviews: 38 employees, 28 leaders (from facilities, regions and national offices), 27 Veteran patients and family members, and four congressional staff members.

APPROACH

Facility and regional leaders were interviewed by telephone, followed by a two-day site visit where employees, patients and family members were interviewed face-to-face. National leaders and congressional staff also completed telephone interviews. Interviews were analyzed using rapid qualitative assessment processes. Themes were mapped to the stages of the Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication model: pre-crisis, initial event, maintenance, resolution and evaluation.

KEY RESULTS

Many areas for improvement during disclosure were identified, such as preparing facilities better (pre-crisis), creating rapid communications, modifying disclosure language, addressing perceptions of harm, reducing complexity, and seeking assistance from others (initial event), managing communication with other stakeholders (maintenance), minimizing effects on staff and improving trust (resolution), and addressing facilities’ needs (evaluation).

CONCLUSIONS

Through the partnership, five recommendations to improve disclosures during each stage of communication have been widely disseminated throughout the VA using non-academic strategies. Some improvements have been made; other recommendations will be addressed through implementation of a large-scale adverse event disclosure toolkit. These toolkit strategies will enable leaders to provide timely and transparent information to patients and families, while reducing the burden on employees and the healthcare system during these events.

KEY WORDS: adverse events, Veterans, qualitative, communication, partnered-based research

INTRODUCTION

The Veterans Health Administration (VA) has strived to become a learning healthcare system, working towards getting the right care to patients when they need it, and then analyzing the results in order to foster improvements.1 The Institute of Medicine identified several strategies for building learning healthcare systems, such as creating new clinical research paradigms, public engagement, science-driven progress and enhanced leadership.1 However, certain types of healthcare learning are more challenging than others, and none are more challenging than studying care breakdowns such as large-scale adverse events.2,3 Disclosure of large-scale adverse events is a formal process by which healthcare system officials assist with coordinating the notification to multiple patients that they may have been affected by a system issue during their care.4 Efforts to improve these disclosure processes are where this new research paradigm is most needed (Fig. 1).

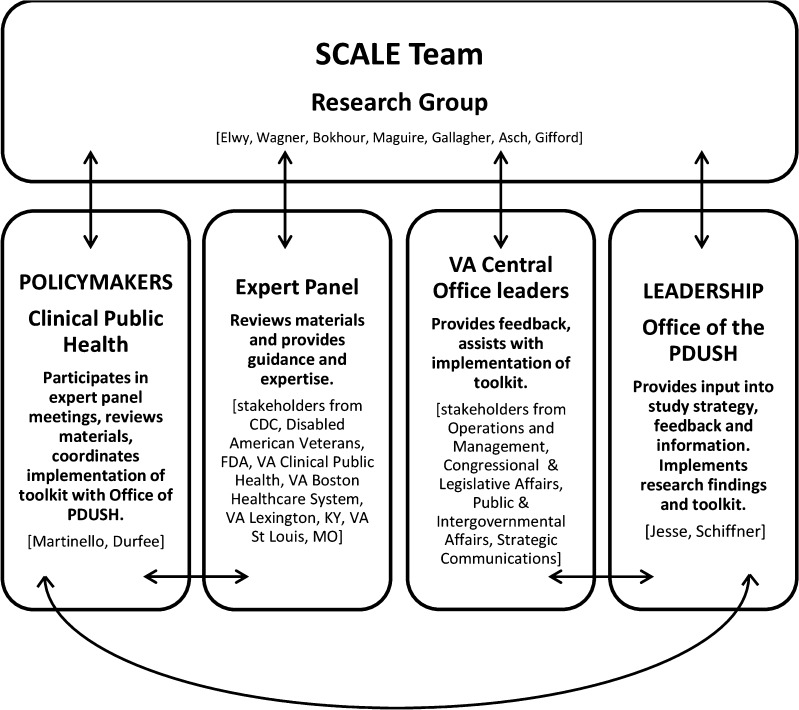

Figure 1.

Partnerships and communication patterns involved in the study. Lines indicate communication patterns across partner groups. PDUSH Principal Deputy Undersecretary for Health; CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; FDA Food and Drug Administration; VA Department of Veterans Affairs.

The VA has several advantages as a healthcare system to improve disclosure of large-scale events. It has a well-developed system for detecting and analyzing potential adverse events.5 It also has an explicit policy on adverse event disclosures stating an obligation to disclose to patients adverse events that have been sustained in the course of their care.4 Finally, the VA has a strong history of improvement partnerships between researchers and system leaders.6

The VA recognized the challenges it has faced during large-scale disclosures, specifically around timely decision-making and effective communication with internal and external stakeholders. Because of these challenges, the Office of the Principal Deputy Under Secretary for Health, the equivalent of a private sector Chief Executive Officer, and Clinical Public Health policymakers (the VA’s equivalent to state and local departments of public health) sought a partnership with health services researchers, patients and families to facilitate a deeper understanding of the obstacles of current disclosure processes resulting in lack of trust from many stakeholders, and to guide process improvement. Through a request for proposals and peer review process, our proposal was funded; it outlined four interlocking studies to examine past disclosures and consequences of these, guided by the Crisis and Effective Risk Communication (CERC) model.7 We chose the CERC model because it combines effective crisis and effective risk communication principles into one model that views communication as a series of five developmental stages. These stages consist of pre-crisis (a research or strategy stage), initial event, maintenance, resolution and evaluation (Table 1).

Table 1.

CERC Model Stages and Descriptions

| CERC Model Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Pre-Crisis | Communication campaigns targeted to both the public and the response community to facilitate: •Public preparation for the possibility of an adverse event •Alliances and cooperation with stakeholders •Message development and testing for subsequent stages |

| Initial Event | Rapid communication to the public and to affected groups seeking to establish: •Reassurance and reduction in emotional turmoil •General understanding of the crisis circumstances, consequences, and anticipated outcomes •Reduction of crisis-related uncertainty •Understanding of self-efficacy/personal response activities |

| Maintenance | Communication seeking to facilitate: •Understanding of background factors and issues •Ongoing explanation and reiteration of self-efficacy/personal response activities •Feedback from affected public and correction of any misunderstandings or rumors |

| Resolution | Public communication seeking to: •Inform about ongoing remediation and recovery •Facilitate broad-based, open discussion and resolution of issues regarding cause and adequacy of response |

| Evaluation | Communication directed toward agencies and the response community to: •Evaluate responses •Document and communicate lessons learned |

This paper describes the partnership required and the methods needed for carrying out one study to improve disclosures of large-scale adverse events: a qualitative interview study with a range of stakeholders at nine facilities to address four research questions: 1) What processes are effective as part of the disclosure process and are effective for minimizing unintended effects?; 2) What processes are effective after disclosure for reducing adverse events arising from notification?; 3) What is the impact of disclosure on employees working at the facilities where the adverse events took place?; and 4) What is the impact of disclosure on patients and their family members?

In line with the VA’s Strategic Plan 2014–2020, Objective 2.2, to enhance the VA’s partnership with other federal agencies and Veterans Service Organizations.8—organizations akin to patient advocacy groups—our partnership team was enhanced by the creation of an Expert Panel to guide all aspects of the study. This Panel included communication experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, other divisions of the VA, and the Disabled American Veterans Service Organization.

The Figure illustrates the groups and interactions involved in our leadership, policymaker, research, and stakeholder partnership. All members of the research and policymaker teams met monthly, and the Expert Panel was convened four times for feedback and problem solving. Our leadership partners brought other VA central office groups into our partnership to ensure implementation of research results. Seven presentations to these VA leadership teams took place to present preliminary results, encourage early feedback, discuss methods for implementing early results in practice, and to alleviate any organizational concerns.

METHODS

Nine large-scale disclosures of adverse events between 2009 and 2013 were selected for study, because they represented different types of events and offered patients follow-up bloodborne pathogen testing (HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C) following disclosure. This allowed the team to examine patients’ behaviors in response to disclosure communication. Bloodborne pathogen testing was recommended because of improper cleaning of medical equipment or equipment reuse. Events included unanticipated system errors, as well as errors made by individual providers. Our original proposal identified six disclosures for study. However, during the study, the leadership and policymaker teams asked researchers to add three, recent disclosures to the protocol. Although two of these disclosures (Sites 7 and 9) did not involve bloodborne pathogen testing, our partners believed that important information on the effects of these disclosures on staff and patients would be uncovered through our examination. Table 2 provides information on the nine disclosures examined and the CERC model stage of disclosure each site was in at the time of study.

Table 2.

Description of Nine Large-Scale Adverse Events for Analysis

| Facility/CERC model stage | Exposure description | Number of patients included in disclosure | Date of disclosure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 Evaluation stage |

Improperly reprocessed ENT endoscopes | 1,104 | February 2009 |

| Site 2 Evaluation stage |

Improper disinfection of auxiliary water tubing system used during colonoscopy reprocessing | 6,805 | February 2009 |

| Site 3 Evaluation stage |

Improper disinfection of auxiliary water tubing system used during colonoscopy reprocessing | 2,531 | March 2009 |

| Site 4 Evaluation stage |

Improper reprocessing of dental equipment | 1,812 | June 2010 |

| Site 5 Evaluation stage |

Improper infection control practices and techniques performed by a particular dentist over the course of several years | 535 | February 2011 |

| Site 6 Resolution stage |

Needle reuse as a result of drug diversion from one radiology technician | 168 | July 2012 |

| Site 7 Evaluation stage |

Clinic-use–only prescription inappropriately prescribed for at home use with side effects of birth defects | 982 | March 2012 |

| Site 8 Resolution stage |

Improper insulin pen reuse (needles were changed) | 716 | January 2013 |

| Site 9 Maintenance stage |

Improper surgeries by a particular podiatrist over the course of several years | 286 | January 2013 |

Institutional Review Board approval for the study was provided by the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital. We conducted semi-structured interviews to assess stakeholders’ understanding of the important elements in the disclosure process (all groups), examine their perceptions of the disclosure and how these impacted future health-seeking behavior (patients and families), explore how disclosures impacted staff morale, perceptions and communication about the event with patients (employees and leaders), and to identify potential improvements for future implementation (all groups).

Procedure for Leadership Interviews

Researchers first contacted facility and regional leaders, to invite them to participate in phone interviews prior to a site visit. All but one leader who was invited to participate in a phone interview did so, and many encouraged the team to contact other facility and regional leaders as well. National leaders were invited to participate in telephone interviews. Because healthcare system leaders were part of our team, we limited the distribution of their names to reduce perceived coercion for participation in the study. The research team did not audiorecord these leadership interviews, in order to encourage as much honesty and transparency about the disclosure process as possible. Extensive handwritten notes were taken during the interview.

Procedure for VA Employee Interviews

Facility and regional leaders gave the team permission to visit the site and conduct face-to-face interviews with employees willing to participate in a confidential interview. The team emailed employees in advance of the two-day site visit to invite their participation in the study. Follow-up emails were sent as needed. We sought to interview up to ten employees at each site.

Procedure for Patient and Family Interviews

Facilities compiled a list of patients (with addresses and phone numbers) who had been notified of the large-scale adverse event. Patients were excluded if they were involved in a formal complaint process or had died since the disclosure. Invitational letters, along with a screening survey and stamped envelope, were sent via mail to patients’ homes.10 We contacted patients by telephone to schedule interviews if patients returned the screening survey and indicated that they were interested in participating in a research interview. Patients’ travel time to the VA facility was often more than 2 h, and in these cases, telephone interviews were scheduled instead of face-to-face visits. We sought to interview up to five patients and five family members at each site.

Procedure for Congressional Staff Member Interviews

During interviews with leaders, we learned that both local and national members of Congress and their staff played significant stakeholder roles during and after the disclosure process, similar to a private sector’s Board of Directors. Our Expert Panel supported our decision to add this group to the study protocol. Congressional staff members with an interest in Veterans’ affairs were contacted, and asked if they would participate in a voluntary, confidential telephone interview. Congressional interviews were not audiorecorded, following the same procedure as leadership interviews. We sought to interview congressional staff members until we reached thematic saturation.11

Interviews

Separate, semi-structured interview guides were constructed for leadership, employee, patient, family member and congressional interviews. Table 3 includes example questions from the guides. Each leader was asked about the unfolding of events, including how she/he was informed of the event, the processes of informing others, and the disclosure to patients and the media. Patient and family interviews involved asking how each found out about the event, what actions they took in response to notification, how concerned they were, and whether the disclosure impacted their perceptions of risk of harm, anxiety, distress or trust in VA. We also probed regarding their exposure to media reports about the event and how this affected their perceptions of the event, the implications for their health and the VA. Employees were asked how they first heard about the event, what their reaction was to this, how prepared they were to handle patients’ questions and what their experiences were with patients during this time. Employee, Veteran and family interviews that took place in person involved written informed consent and participants’ agreement to be audiorecorded. Interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Table 3.

Example Interview Questions by Interview Type

| Question | Interview Type |

|---|---|

| What kind of communication did you receive regarding this event? | L, E, P, F, C |

| What did you do when you found out? | L, E, P, F, C |

| What went well with the disclosure process? | L, E, C |

| What needs improvement? | L, E, C |

| What would you have done differently when communicating with patients and the public if you had to repeat this event again? | L, E |

| Who else outside of the VA did you communicate with about the event? | L, E |

| What other ways did you hear about the event? | E, P, F |

| Do you feel you had an opportunity to share your thoughts with the VA? | P, F |

| How do you feel about the VA now? | P, F |

| How important do you think it was that you were told about this event? | P, F |

| What kind of support did you feel you needed but did not receive? | L, E |

L leadership; E employee; P patient; F family member; C Congressional staff member

Analysis of Interviews

Field notes were taken on all participants’ interviews, and were used together with the interviewer notes or transcriptions in the analysis. We conducted grounded thematic analyses of all interviews at each site within 2 weeks of the site visit.11, 12 We used rapid assessment procedures, an anthropological approach for assessing real-time processes and procedures to rapidly inform policy development.13 We examined the data for evidence of the important elements of disclosure that should be included with each notification, leaders’, patients’, employees’ and congressional staff members’ perceptions of how disclosure impacted patients’ perceptions of risk of harm, anxiety, distress, trust in VA, and how the disclosure process impacted Veterans’ self-efficacy in carrying out needed tasks, such as scheduling blood tests and follow-up visits. We also coded for instances where participants discussed the impact of media coverage on their perceptions of disclosures, and for suggestions they reported for future disclosures procedures.

RESULTS

Below, we present results from the qualitative data analyses as well as our observations of the partnership process.

Thematic Analyses

We interviewed 38 employees, 28 leaders, 27 patients and family members and four congressional staff members. Ten overall themes describing what went well and what needed to improve in previous disclosures emerged through analysis of the 97 interviews. We mapped each theme according to the stage of the CERC model in which it fit best, to develop strategies to address these disclosure challenges in the future, and to emphasize evidence of disclosure effectiveness when it was present. The ten themes included a need for better facility preparation (pre-crisis stage); creating rapid communications, modifying language as part of the disclosure, addressing perceptions of harm, reducing complexity in the disclosure process, and seeking assistance from others (initial event stage); managing communication with others (maintenance stage); decreasing effects on staff, improving trust (resolution stage); and addressing identified needs (evaluation stage). In the themes below organized by CERC model stage, we provide representative quotes on what went well and what needs improving for each theme, across the variety of stakeholders in the study. Table 4 contains more extensive quotes, providing evidence for each theme.

Table 4.

Interview Themes and Quotes by CERC Model Stage

| CERC model stage | Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Crisis | Better facility preparation | Regional leader: “When this happens, it feels like everyone is scrambling. We need to figure out an approach and have it in place for when endoscopes or dental service or Katrina happened.” |

| Initial event | Creating rapid communications | Patient: “I was just surprised that the letter took so long and then the info in the letter was the same as what we had talked about on the phone—there was nothing new. I was expecting it to tell me when my appointment was.” |

| Modifying language | Patient: “The first paragraph, last sentence, they say ‘discovered’ which seems like it was something new they just found out about. It had been going on for a long time. Then the last sentence ‘While we are deeply regret…’ that’s B.S. They’re trying to make like it was all one guy at fault but they covered it up for years. It took the VA a long time to get the right people to work on it.” | |

| Addressing perceptions of harm | Patient: “That was one of those that the first question pops in your mind. And the, you know, how ‘bout if it on me? Did I get, did I get contaminated or not? You know, that’s how you got scared…It is important that, you know, they got their record, they went through the process to find out who was and who was not. I think that was the right, the right procedure.” | |

| Reducing complexity | Facility leader: “One of the things is having one point of contact. There was a day when I gotten calls asking for the same piece of information. If there was one contact, I could have saved a lot of time responding to requests and only answered once.” | |

| Seeking assistance from others | Facility staff: “I reached out to.facility] because there was some stuff on the Sharepoint that [facility] had put together, but it really wasn’t enough detail to help us with the nuts and bolts of how to put this data plan together. So we kinda in secret called the clinical application coordinator at [facility] and said, you know, ‘what should we be looking out for, what are we not thinking about, how can you help us?’ And they were very helpful, incredibly helpful.” | |

| Maintenance | Managing communication with others (media, elected officials, service organizations) | Facility leader: “We had a conference call for those who couldn’t join the in person meeting. I gave a full briefing and gave them firsthand information. We gave the bullet points on a handout. It was very helpful, more open. We had the right people at the table to answer their questions. There was no time limit for the meeting; I wanted to be sure they had all the info they needed |

| Resolution | Decreasing effect on staff | Facility staff: “The first m–, uh, month I had an enormous amount of anxiety. Um, I had no idea what I was doing. I was in a system that I was unfamiliar with and I just was overwhelmed. I was working probably 10 to 12 h a day 5 days a week and, um, it affected my home life.” |

| Improving trust | Facility staff: “My feeling was that we did more harm to patients than we did good for them um, because the anxiety they went through the, and, and, and really big harm is the loss in trust in the facility.” | |

| Evaluation | Addressing identified needs | Facility staff: “We’ve just bashed our head against the wall so many times with this and it’s just silly that, you know, we, that there isn’t a central clearing house of information—a set of, you know, recommendations everyone can follow.” |

CERC Model: Pre-Crisis; Theme: Better Facility Preparation

Facilities that had developed a culture of open communication between leaders and employees before a crisis occurred reported more positive communication during and after the adverse event. As one facility leader said, reflecting on what went well with communication at his facility, “Staff felt they could be open. They were coming up to my office and they weren’t afraid anything would happen to them.”

Problems occurred when facilities did not have a pre-existing culture of open communication and transparency. We learned from many participants about the various ways in which facilities and leaders can strengthen the VA’s approach to disclosure in the pre-crisis stage by improving its relationship with the media, transparency with its employees and patients, and by developing in-house communication expertise.

CERC Model: Initial Event; Theme: Creating Rapid Communications

There were issues with the execution of rapid communications to affected groups during the initial event phase. Most facilities in the study first sent certified letters to patients instead of making phone calls. One patient explained, “I don’t like to get certified mail, because, I don’t know, maybe it’s psychological, but it always seems that it’s always bad news.” Patients and family members expressed having a difficult time with disclosure when it became apparent that the disclosure had been delayed. As one patient stated: “I did think it was weird that it took them a whole year to come up and contact us about this. I asked about that over the phone and she said she didn’t know why it took so long. I wanted to know quicker, at least within a couple of months.”

CERC Model: Initial Event; Theme: Addressing Perceptions of Harm

Participants identified minimizing patients’ and family members’ perceptions of harm and increasing trust as important aspects of the disclosure. Facilities developed hotlines to answer patient questions during the initial event. They also planned testing clinics where patients could meet with providers to discuss the event and be tested. The goals of these processes were to provide reassurance and reduce anxiety. One patient described his experience coming in to the testing clinic: “They gave you a pamphlet and booklet. There was a presentation and then a nurse talked to you. It was real good.”

CERC Model: Initial Event; Theme: Modifying Language

Some facilities made phone calls to patients before sending a letter, with language modified for phone purposes, which was appreciated by patients. As one patient stated, “I was glad I got the call first. With a letter, you see one word and it can upset you. Like seeing ‘HIV.’ When I talk with someone on the phone, they were able to reassure me.”

CERC Model: Initial Event; Theme: Reducing Complexity

The complexity of the disclosure process, and the layers of approvals required from VA officials, often led to disclosure delays. One regional network director stated, “When we had information ready for the media, a lot of layers of [VA] Central Office had to go through the process of approving those communications. When that happened, we had to wait. So by waiting we’re not able to be as responsive to congressional staff and to the media. When those things happen, people start wondering: Why don’t we know about this? What’s happening? And that was a problem.”

CERC Model: Maintenance; Theme: Managing Communication with Others

Employees and leaders detailed the extensive steps they took to communicate with patients and provide options for testing during this stage. Communication with all employees was one area for improvement. Employees who were not part of the disclosure team did not receive ongoing updates. Patients asked questions of all employees during this time, leaving many in a difficult position of having no information to provide patients. Reflecting on this, one facility leader described ongoing communications to assure that all employees were aware of the situation at all times: “All staff should be up to date on the event, send out a blanket email or have a town hall meeting, so they all know what has happened and are ready to help the Veterans.”

CERC Model: Resolution; Theme: Minimizing Effects on Staff

Our interviews showed that leaders had spent time reflecting on the adequacy of the organization’s response to the event. Two of the sites were in the resolution stage and had identified the impact of events on employees and patients’ trust. However, recovery from issues has not been reached at many facilities. One leader expressed enduring issues: “Devastation, and it’s still ongoing. They tried to address it by turning over leadership…the really sad part is the lasting impact on staff. We’re not even sure if anything was really contracted as a result—and no one outside the VA understands that. It is ongoing. We really need to identify a few people who can develop expertise in this and support the process.”

CERC Model: Resolution; Theme: Improving Trust

Many employees discussed patients’ potential loss of trust through the disclosure process and indicated that some groups of patients, especially those with pre-existing experiences or conditions that make them wary of VA services, may require tailored disclosure notifications: “In military sexual trauma, I think we saw a number of the most difficult disclosures. There were only really a handful with people who had a strong military sexual trauma and sort of victimized, they had been victimized and they saw this [the disclosure] in that context—and it was harder for them.”

CERC Model: Evaluation; Theme: Addressing Identified Needs

All who were interviewed had examples of lessons learned from these disclosures. Congressional staff members, who often directly communicate with both leaders and the media, offered suggestions on how the organization could establish better relationships with stakeholders through the media, in what would be described as pre-crisis activities: “VA sometimes gets unfairly beat up in the media, but they do it to themselves too. They should reach out to the media about positive stuff. VA has good, successful programs that are liked by Veterans and families, but they don’t help themselves out by talking about those programs.”

Although leaders and employees all shared lessons learned, they also identified the need for a formal process to share these lessons with others. One regional leader expressed a desire for more training based on these lessons: “We have not done case studies for network directors and we have many new network directors and a lot of them have not been involved with an institutional disclosure. We could develop case studies and talk to network directors about what goes right and what goes wrong, and be candid about the process.”

Observations on the Partnership

Often with research, findings are written into manuscripts and presented at academic meetings. However, through our close relationship with leaders and policymakers, we have presented these results and suggestions for improvements through a White Paper.9 and seven presentations to VA leaders and policymakers including national staff of the Office of Public Health, Department-level offices outside of healthcare who also seek improvements in communication patterns, and to private sector consulting groups working with the VA on improving disclosure processes. Our Expert Panel became both users of the study results, as well as guiding the study. Some improvements have already been implemented and have become part of routine practice. In the 2013 disclosures, all patients received a phone call first, to notify them of the event, and this was then followed by a regular U.S. mail letter, instead of a certified letter, detailing the information about the adverse event and suggesting follow-up care. The recommendations presented below are scheduled to be implemented through implementation of our disclosure of a large-scale adverse event toolkit, the final phase of our study. Dissemination efforts recently began through telephone and in-person meetings with various stakeholders to create leadership support, buy-in and communication networks so critical for successful national implementation efforts.15

Having a team consisting of diverse partners encouraged methodological decision-making not usually considered in research paradigms, such as the valuable decision to not audiorecord leadership interviews. One leader specifically stated, “because you are not recording this, I will tell you…”. An aspect of the tension of the new research partnership paradigm is the need for research to be implementation-ready at an early stage in the process. As one leader attending a presentation stated, “I don’t have time to wait for the final products, we’re implementing these results now.” Researchers, who are accustomed to the steady track of finishing projects, preparing final reports and disseminating results through peer-reviewed publications, may feel slightly unnerved about such a rapid decision to implement preliminary results. However, to encourage learning healthcare systems, we want the organization to respond to our empirical results in such a manner. Becoming familiar with this new paradigm and recognizing the shortened time frame in the research process will enable greater comfort and responsiveness from all sides of the partnership.

DISCUSSION

Many lessons learned emerged through our stakeholder interviews, resulting in an evaluation that provides direction for future disclosure decision-making and links to the pre-crisis stage of preparation. All patients indicated that although the disclosure initially caused distress, the VA did the right thing in notifying them of potential exposures and offering testing and follow-up care. Employees felt that more harm than good came to patients as a result of disclosure, primarily because employees felt that patients no longer placed trust in the VA. These feelings may have arisen because employees often took the brunt of patients’ harsh reactions when adverse events occurred, while not feeling prepared for these reactions because employees were not always notified of the adverse events in a timely way. Keeping all employees, but especially the front-line employees responsible for outreach and communication with patients, fully informed from the initial awareness of the adverse event through the resolution stage, will help employees understand the organizations’ response to the adverse event. Seeking frequent employee feedback and creating a culture of transparency will help as well.

Findings from this qualitative study of 97 participants at nine sites have resulted in the following five recommendations for future disclosures of adverse events, to be implemented in our toolkit. Importantly, our recommendations are in line with a recent report advocating for improved communication throughout the VA healthcare system.14 While the issues of access to VA services and VA integrity prominent in current public conversation are not directly related to the disclosure of adverse events in patient care, we feel that the findings from our study are very relevant to the VA as these internal problems are defined and analyzed and the VA works to resolve these issues and regain the public’s trust.

1. Preparation is needed in the pre-crisis stage to identify processes and support needed for facilities to conduct disclosures. These preparations could involve case study training for leaders, developing a database of exemplar practices created by previous sites who have undergone disclosures, training public affairs officers and others responsible for communication on effective risk communication principles, and establishing strong relationships with the community in advance of any crisis by working with the media to highlight popular programs at VA facilities and Veterans’ appreciation of them.

2. Local and regional facilities should establish procedures for bringing together all people who need to be involved in disclosure in one setting to seek input and approval at one time. This will reduce the complex organizational communication patterns that affect the timing and execution of disclosure to patients and families at the initial event stage.

3.Communication should be tailored to patients who have pre-existing conditions that may impact how they perceive the disclosure, such as those who suffer from military sexual trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder. While it will initially add to the complexity to identify these pre-existing conditions, this tailoring will likely lead to less distress for these patients, family members and the employees who have contact with them during and after the disclosure process.

4. Healthcare systems undergoing disclosures of large-scale adverse events need to work on continued messaging about the event and helping the public understand the risks. This sustained messaging is an essential aspect of the maintenance stage, and offers a time for systems to refute rumors and offer evidence-based information on the cause of the event and the strategies the healthcare system is undertaking to prevent these events in the future.

5. In order for an organization to come to resolution about the event, more internal communications that address these worries need to take place, through leadership’s consistent feedback to all employees. Weekly emails and printed materials updating employees on continued efforts of the organization to improve quality and safety at the hospital, new initiatives undertaken to address these, and seeking employee input will enable resolution to be achieved.

Disclosing adverse events is a highly sensitive undertaking for any healthcare organization. Only through our leadership, policymaker, research and stakeholder partnership was our team able to investigate past disclosures from the perspective of patients, family members, employees, leaders and stakeholders outside the organization, and make disclosure recommendations for any future large-scale adverse events that may occur.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Service, SDR 11–440. The views, opinions, and content of this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Drs. Elwy, Bokhour, Maguire, Asch and Gifford are supported by the HIV/Hepatitis Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, Veterans Health Administration.

Dr. Elwy is also an investigator with the Implementation Research Institute, at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis, through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25 MH080916-01A2) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

RLJ is now in another position with the VHA. SS has retired.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary (IOM Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine). National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.; 2007.

- 2.Dudzinski DM, Hebert PC, Foglia MB, Gallagher TH. The disclosure dilemma—Large scale adverse events. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:978–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhle1003134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prouty CD, Foglia MB, Gallagher TH. Patients’ experiences with disclosure of a large-scale adverse event. J Clin Ethics. 2013;24:353–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration Handbook 1004.08, Disclosure of Adverse Events to Patients, Washington, D.C., October 2, 2012.

- 5.Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Handbook 1050.1 VHA National Patient Safety Improvement Handbook. January 30, 2002.

- 6.Stetler CB, Mittman BS, Francis J. Overview of the VA Quality EnOverview of the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) and QUERI theme articles: QUERI Series. Impl Sci. 2008;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds B, Seeger MW. Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. J Health Comm. 2005;10:43–55. doi: 10.1080/10810730590904571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Veterans Affairs, Strategic Performance Plan, Fiscal Year 2014–2020, Washington, D.C. http://www.va.gov/performance/ Accessed August 26, 2014.

- 9.Elwy AR, Maguire EM, Bokhour BG, Gifford AL, Asch SM, Wagner T, Gallagher T, Burgess J, Durfee JM, Martinello R. Communicating Large Scale Adverse Events: Lessons from Media Reactions to Risk: White Paper. Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service, September 2012.

- 10.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Melani Christian L. Internet, mail and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 3rd ed, 2009.

- 11.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA

- 12.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd ed., Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994.

- 13.Utarini A, Winkvist A, Pelto GH. Appraising Studies in Health Using Rapid Assessment Procedures (RAP): Eleven Critical Criteria. Human Organization. 2001;60(4):390–400. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The American Legion. VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. System Worth Saving Report. November 5–6, 2013. http://www.legion.org/publications/218184/2013-sws-report-va-pittsburgh-healthcare-system Accessed August 26, 2014.

- 15.Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) Impl Sci. 2013;8:51. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]