Abstract

Purpose

We previously demonstrated that 48% of patients with pain at sites of previously irradiated bone metastases benefit from reirradiation. It is unknown whether alleviating pain also improves patient perception of quality of life (QOL).

Patients and Methods

We used the database of a randomized trial comparing radiation treatment dose fractionation schedules to evaluate whether response, determined using the International Consensus Endpoint (ICE) and Brief Pain Inventory pain score (BPI-PS), is associated with patient perception of benefit, as measured using the European Organisation for Resesarch and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) and functional interference scale of the BPI (BPI-FI). Evaluable patients completed baseline and 2-month follow-up assessments.

Results

Among 850 randomly assigned patients, 528 were evaluable for response using the ICE and 605 using the BPI-PS. Using the ICE, 253 patients experienced a response and 275 did not. Responding patients had superior scores on all items of the BPI-FI (ie, general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work, relations with other people, sleep, and enjoyment of life) and improved QOL, as determined by scores on the EORTC QLQ-C30 scales of physical, role, emotional and social functioning, global QOL, fatigue, pain, and appetite. Similar results were obtained using the BPI-PS; observed improvements were typically of lesser magnitude.

Conclusion

Patients responding to reirradiation of painful bone metastases experience superior QOL scores and less functional interference associated with pain. Patients should be offered re-treatment for painful bone metastases in the hope of reducing pain severity as well as improving QOL and pain interference.

INTRODUCTION

Radiation therapy is an effective treatment in painful bone metastases.1 Because improvements in systemic and supportive therapies have increased the life expectancy of patients with advanced cancer, pain may recur, and patients therefore require repeat radiation treatment.2 Although radiation treatment to bone metastases offers no increase in overall survival, many patients benefit from repeat irradiation for symptom relief. In the NCIC Clinical Trials Group Symptom Control (SC.20) randomized controlled trial, we previously reported that among patients previously irradiated for painful osseous metastases, 45% of those receiving a single 8-Gy treatment and 51% treated with 20 Gy in multiple fractions had an overall pain response to repeat irradiation.3

Patients requiring reirradiation often have a more extensive disease burden.2 Thus, it has been questioned whether reirradiation as a local treatment to painful bone metastases has the potential to improve these patients' functional activity and quality of life (QOL). As our primary aim, we performed a secondary analysis of the SC.20 database to determine the impact of reirradiation on changes in QOL and functional independence.

In SC.20, pain response was assessed using the International Consensus Endpoint (ICE), which combines the constructs of pain relief and opioid requirement.4–6 This end point requires greater investment in that data regarding opioid use need to be systematically collected. Several previous bone pain trials have employed pain score only (ie, without accounting for changes in opioid use) to define treatment end point.7,8 As a secondary aim, we again used the SC.20 database to determine if the addition of daily opioid use in the ICE was more closely associated with QOL changes compared with using pain score only.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The SC.20 trial randomly assigned patients to receive either a single- or multiple-fraction treatment for reirradiation of painful bone metastases. The primary end point was overall pain response as measured by the ICE at 2 months after radiation therapy. Results of the primary end point have been previously published.3 Patients were also asked to complete the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) and Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) at baseline and 2 months after reirradiation treatment, consistent with the primary end point of the study.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 was employed to assess patients' QOL. This questionnaire contains five multiple-item subscales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning), six single-item symptom scales (sleep disturbance, constipation, diarrhea, dyspnea, appetite loss, and financial issues), three multiple-item symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and nausea) and a two-item global health status scale.9 All items are rated on a 4-point Likert type scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much), with the exception of the two-item global health status scale, which is rated from 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent). Each subscale is linearly converted to a score ranging from 0 to 100, where a higher score indicates better functioning for the functional scales or greater severity of symptoms for the symptom scales. As part of validation, we analyzed how the responses in both ICE and pain score–only methods were associated with the domains in the EORTC QLQ-C30.

Clinical changes in QOL scores were calculated in accordance with the published guideline for reporting health-related QOL in randomized controlled clinical trials.10 Changes of at least 10 points from the baseline (scale of 0 to 100) were selected to represent a clinically meaningful change in the mean value of the QOL parameter. For functional domains, a mean increase in ≥ 10 points would mean a moderate improvement in average score, whereas a mean decrease of ≥ 10 points would indicate worsening. For symptom domains, the opposite relationship holds (mean decrease by ≥ 10 points would mean moderate improvement). Individual patients were classified as either improved or not based on a 10-point change from baseline. Mean changes of > 20 points were classified as large effects.11 Mean changes of < 10 points were considered not clinically significant. However, in patients with advanced cancer, the magnitude of mean change may not be as large as in patients with early cancer. Therefore, we defined mean change of ≥ 5 but < 10 points as modest improvement. For the BPI, improvement or deterioration by ≥ 2 points was categorized as improved or worsened, respectively. Other changes were categorized as stable.12

The BPI includes an 11-point scale (scores from 0 to 10) to assess pain severity. Patients were to indicate their worst pain (BPI-PS) at the treatment area in the past 3 days. The BPI also includes questions on a scale of 0 to 10 pertaining to functional interference (BPI-FI), asking patients how pain has affected their general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work, relations with other people, sleep, and enjoyment of life.13 We chose to validate the ICE instrument through use of the BPI-FI.

The ICE instrument was used to assess pain severity and analgesic consumption and to categorize patients treated per protocol as responders or nonresponders to reirradiation.5 A complete response to re-treatment was defined as a BPI worst-pain score of 0, with no associated increase in daily oral morphine equivalent consumption (OMEC). A partial response was defined as pain that persisted after re-treatment, either with a worst-pain score reduction of ≥ 2 with no increase in daily OMEC or no increase in pain and a reduction of at least 25% in daily OMEC. Responders included those who achieved complete and partial responses. Nonresponders referred to those who did not fit into these two categories, including patients with pain progression, which was defined as an increase in a worst-pain score of ≥ 2 without decreased daily OMEC or no change in worst-pain score with an increase in daily OMEC of at least 25%. Responders and nonresponders were compared with assess differences in QOL and functional interference after reirradiation.

Statistical Analysis

We previously reported the results of comparing ICE response and changes in BPI-FI and EORTC QLQ-C30 scores at 2 months after radiation therapy in the two randomized arms of the SC.20 trial and concluded that no important differences in outcome were observed between the two randomized groups.3 Therefore, we pooled these two groups to perform all analyses.

The mean and standard deviation of BPI and QOL scores at baseline and the changes from baseline to 2-month follow-up were calculated; 95% CIs were calculated for changes at 2-month follow-up. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the two groups in terms of baseline and changes at 2-month follow-up from baseline.14

For our first objective, we calculated the proportion of patients with clinically meaningful improvement on each domain of the QOL and BPI scales. For each domain, a χ2 test was then performed to compare the proportion of patients who improved between the responders and nonresponders. P value less than .05 indicated statistical significance.

To compare the evaluative and discriminative properties of the consensus end point, the analyses were repeated using the alternate study end point of the BPI-PS only to define responders and nonresponders to treatment. A reduction in the worst pain score of ≥ 2 on the BPI indicated a response to treatment. All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

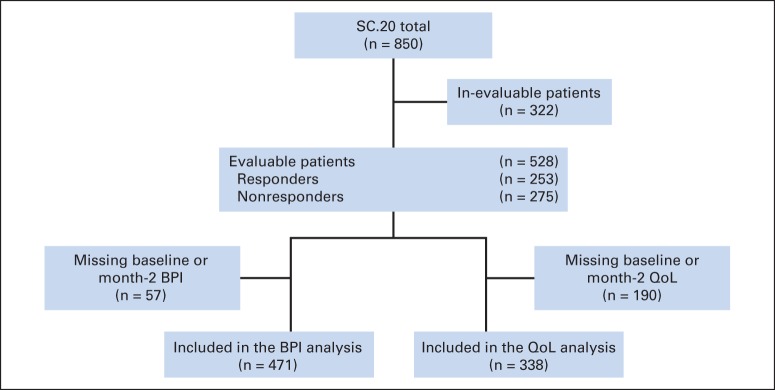

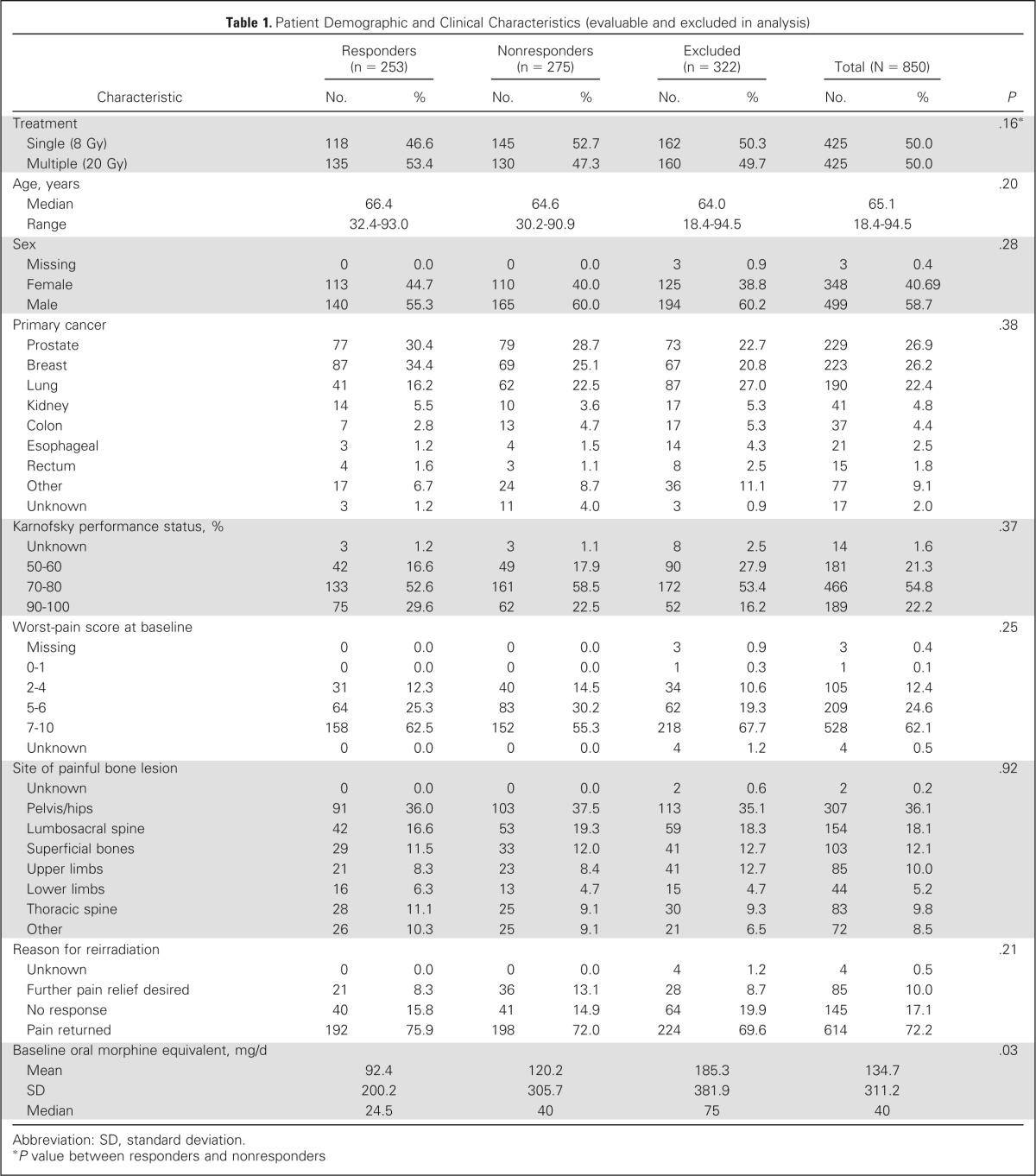

Among 850 randomly assigned patients, 528 were evaluable based on intention-to-treat population for protocol-defined consensus response to re-treatment at 2 months (Fig 1). There were 253 patients (48%) in the responder group and 275 (52%) in the nonresponder group. Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups (Table 1). Two-month follow-up data were complete for the BPI in 471 and for the QLQ-C30 in 338 patients and included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics of patients completing the BPI and QLQ-C30 at 2 months were similar (Data Supplement).

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram. BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; QoL, quality of life; SC.20, NCIC Clinical Trials Group Symptom Control trial.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (evaluable and excluded in analysis)

| Characteristic | Responders (n = 253) |

Nonresponders (n = 275) |

Excluded (n = 322) |

Total (N = 850) |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Treatment | .16* | ||||||||

| Single (8 Gy) | 118 | 46.6 | 145 | 52.7 | 162 | 50.3 | 425 | 50.0 | |

| Multiple (20 Gy) | 135 | 53.4 | 130 | 47.3 | 160 | 49.7 | 425 | 50.0 | |

| Age, years | .20 | ||||||||

| Median | 66.4 | 64.6 | 64.0 | 65.1 | |||||

| Range | 32.4-93.0 | 30.2-90.9 | 18.4-94.5 | 18.4-94.5 | |||||

| Sex | .28 | ||||||||

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.4 | |

| Female | 113 | 44.7 | 110 | 40.0 | 125 | 38.8 | 348 | 40.69 | |

| Male | 140 | 55.3 | 165 | 60.0 | 194 | 60.2 | 499 | 58.7 | |

| Primary cancer | .38 | ||||||||

| Prostate | 77 | 30.4 | 79 | 28.7 | 73 | 22.7 | 229 | 26.9 | |

| Breast | 87 | 34.4 | 69 | 25.1 | 67 | 20.8 | 223 | 26.2 | |

| Lung | 41 | 16.2 | 62 | 22.5 | 87 | 27.0 | 190 | 22.4 | |

| Kidney | 14 | 5.5 | 10 | 3.6 | 17 | 5.3 | 41 | 4.8 | |

| Colon | 7 | 2.8 | 13 | 4.7 | 17 | 5.3 | 37 | 4.4 | |

| Esophageal | 3 | 1.2 | 4 | 1.5 | 14 | 4.3 | 21 | 2.5 | |

| Rectum | 4 | 1.6 | 3 | 1.1 | 8 | 2.5 | 15 | 1.8 | |

| Other | 17 | 6.7 | 24 | 8.7 | 36 | 11.1 | 77 | 9.1 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 1.2 | 11 | 4.0 | 3 | 0.9 | 17 | 2.0 | |

| Karnofsky performance status, % | .37 | ||||||||

| Unknown | 3 | 1.2 | 3 | 1.1 | 8 | 2.5 | 14 | 1.6 | |

| 50-60 | 42 | 16.6 | 49 | 17.9 | 90 | 27.9 | 181 | 21.3 | |

| 70-80 | 133 | 52.6 | 161 | 58.5 | 172 | 53.4 | 466 | 54.8 | |

| 90-100 | 75 | 29.6 | 62 | 22.5 | 52 | 16.2 | 189 | 22.2 | |

| Worst-pain score at baseline | .25 | ||||||||

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.4 | |

| 0-1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| 2-4 | 31 | 12.3 | 40 | 14.5 | 34 | 10.6 | 105 | 12.4 | |

| 5-6 | 64 | 25.3 | 83 | 30.2 | 62 | 19.3 | 209 | 24.6 | |

| 7-10 | 158 | 62.5 | 152 | 55.3 | 218 | 67.7 | 528 | 62.1 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.2 | 4 | 0.5 | |

| Site of painful bone lesion | .92 | ||||||||

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.2 | |

| Pelvis/hips | 91 | 36.0 | 103 | 37.5 | 113 | 35.1 | 307 | 36.1 | |

| Lumbosacral spine | 42 | 16.6 | 53 | 19.3 | 59 | 18.3 | 154 | 18.1 | |

| Superficial bones | 29 | 11.5 | 33 | 12.0 | 41 | 12.7 | 103 | 12.1 | |

| Upper limbs | 21 | 8.3 | 23 | 8.4 | 41 | 12.7 | 85 | 10.0 | |

| Lower limbs | 16 | 6.3 | 13 | 4.7 | 15 | 4.7 | 44 | 5.2 | |

| Thoracic spine | 28 | 11.1 | 25 | 9.1 | 30 | 9.3 | 83 | 9.8 | |

| Other | 26 | 10.3 | 25 | 9.1 | 21 | 6.5 | 72 | 8.5 | |

| Reason for reirradiation | .21 | ||||||||

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.2 | 4 | 0.5 | |

| Further pain relief desired | 21 | 8.3 | 36 | 13.1 | 28 | 8.7 | 85 | 10.0 | |

| No response | 40 | 15.8 | 41 | 14.9 | 64 | 19.9 | 145 | 17.1 | |

| Pain returned | 192 | 75.9 | 198 | 72.0 | 224 | 69.6 | 614 | 72.2 | |

| Baseline oral morphine equivalent, mg/d | .03 | ||||||||

| Mean | 92.4 | 120.2 | 185.3 | 134.7 | |||||

| SD | 200.2 | 305.7 | 381.9 | 311.2 | |||||

| Median | 24.5 | 40 | 75 | 40 | |||||

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

P value between responders and nonresponders

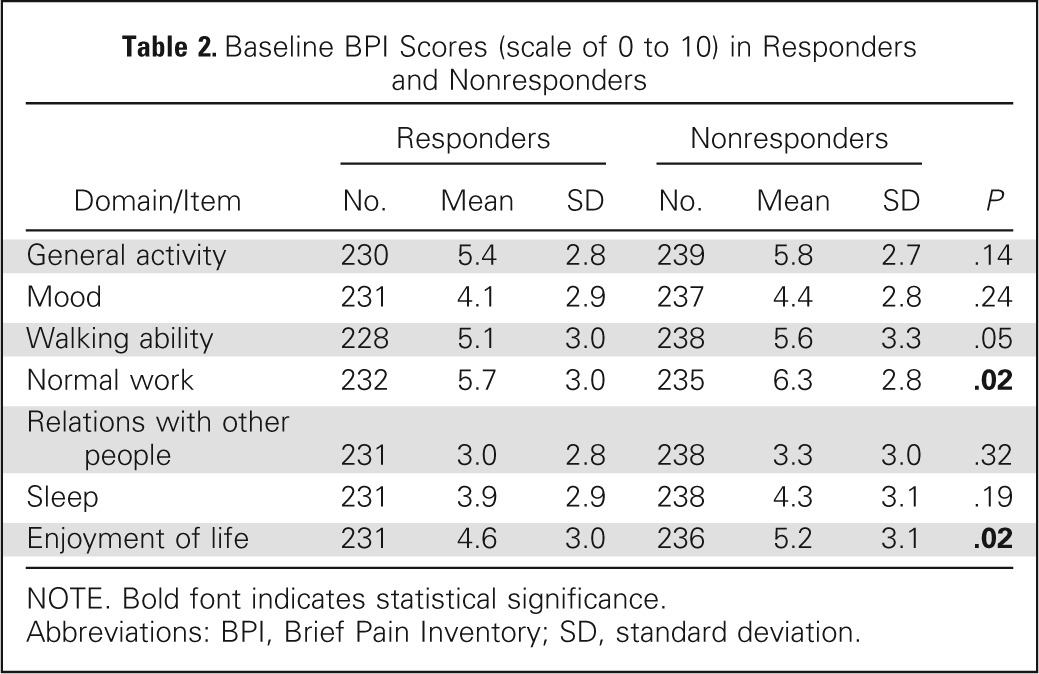

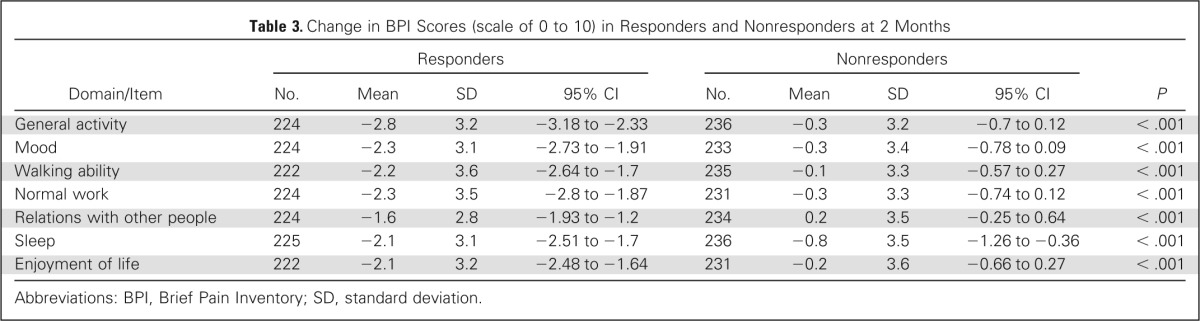

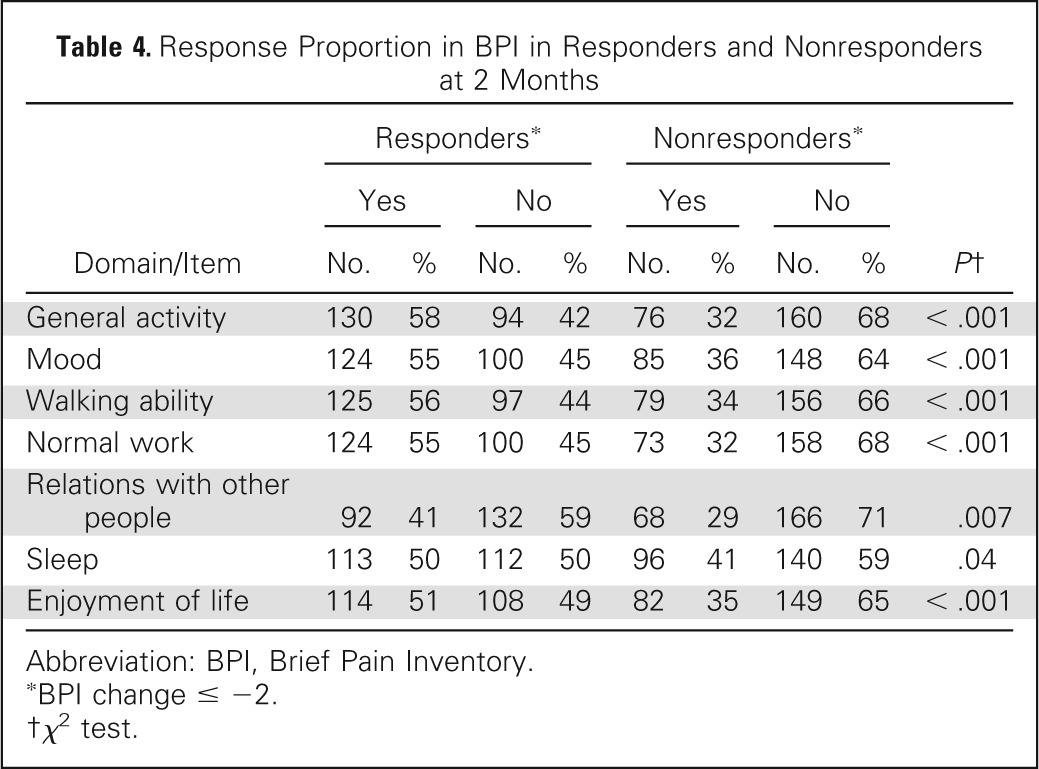

The baseline BPI-FI scores were similar between the ICE responder and nonresponder groups except in normal work and enjoyment of life, indicating that baseline pain in responders was less likely to interfere with work or enjoyment of life. There was a trend (P = .05) for improved walking ability at baseline in responders (Table 2). At 2 months, greater reductions in scores for all BPI-FI items as compared with baseline scores were observed in the ICE responder group as compared with the nonresponder group. Responders had mean reductions of ≥ 2 points on all items except relations with other people; mean reduction scores were < 1 point in all domains for nonresponders (Table 3; Appendix Fig A1, online only). Comparing the proportion of clinically meaningful changes between the ICE responders and nonresponders with improvement by ≥ 2 points, all seven BPI-FI items were all statistically different in favor of the responders (Table 4).

Table 2.

Baseline BPI Scores (scale of 0 to 10) in Responders and Nonresponders

| Domain/Item | Responders |

Nonresponders |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | No. | Mean | SD | ||

| General activity | 230 | 5.4 | 2.8 | 239 | 5.8 | 2.7 | .14 |

| Mood | 231 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 237 | 4.4 | 2.8 | .24 |

| Walking ability | 228 | 5.1 | 3.0 | 238 | 5.6 | 3.3 | .05 |

| Normal work | 232 | 5.7 | 3.0 | 235 | 6.3 | 2.8 | .02 |

| Relations with other people | 231 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 238 | 3.3 | 3.0 | .32 |

| Sleep | 231 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 238 | 4.3 | 3.1 | .19 |

| Enjoyment of life | 231 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 236 | 5.2 | 3.1 | .02 |

NOTE. Bold font indicates statistical significance.

Abbreviations: BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Change in BPI Scores (scale of 0 to 10) in Responders and Nonresponders at 2 Months

| Domain/Item | Responders |

Nonresponders |

P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | 95% CI | No. | Mean | SD | 95% CI | ||

| General activity | 224 | −2.8 | 3.2 | −3.18 to −2.33 | 236 | −0.3 | 3.2 | −0.7 to 0.12 | < .001 |

| Mood | 224 | −2.3 | 3.1 | −2.73 to −1.91 | 233 | −0.3 | 3.4 | −0.78 to 0.09 | < .001 |

| Walking ability | 222 | −2.2 | 3.6 | −2.64 to −1.7 | 235 | −0.1 | 3.3 | −0.57 to 0.27 | < .001 |

| Normal work | 224 | −2.3 | 3.5 | −2.8 to −1.87 | 231 | −0.3 | 3.3 | −0.74 to 0.12 | < .001 |

| Relations with other people | 224 | −1.6 | 2.8 | −1.93 to −1.2 | 234 | 0.2 | 3.5 | −0.25 to 0.64 | < .001 |

| Sleep | 225 | −2.1 | 3.1 | −2.51 to −1.7 | 236 | −0.8 | 3.5 | −1.26 to −0.36 | < .001 |

| Enjoyment of life | 222 | −2.1 | 3.2 | −2.48 to −1.64 | 231 | −0.2 | 3.6 | −0.66 to 0.27 | < .001 |

Abbreviations: BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; SD, standard deviation.

Table 4.

Response Proportion in BPI in Responders and Nonresponders at 2 Months

| Domain/Item | Responders* |

Nonresponders* |

P† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| General activity | 130 | 58 | 94 | 42 | 76 | 32 | 160 | 68 | < .001 |

| Mood | 124 | 55 | 100 | 45 | 85 | 36 | 148 | 64 | < .001 |

| Walking ability | 125 | 56 | 97 | 44 | 79 | 34 | 156 | 66 | < .001 |

| Normal work | 124 | 55 | 100 | 45 | 73 | 32 | 158 | 68 | < .001 |

| Relations with other people | 92 | 41 | 132 | 59 | 68 | 29 | 166 | 71 | .007 |

| Sleep | 113 | 50 | 112 | 50 | 96 | 41 | 140 | 59 | .04 |

| Enjoyment of life | 114 | 51 | 108 | 49 | 82 | 35 | 149 | 65 | < .001 |

Abbreviation: BPI, Brief Pain Inventory.

BPI change ≤ −2.

χ2 test.

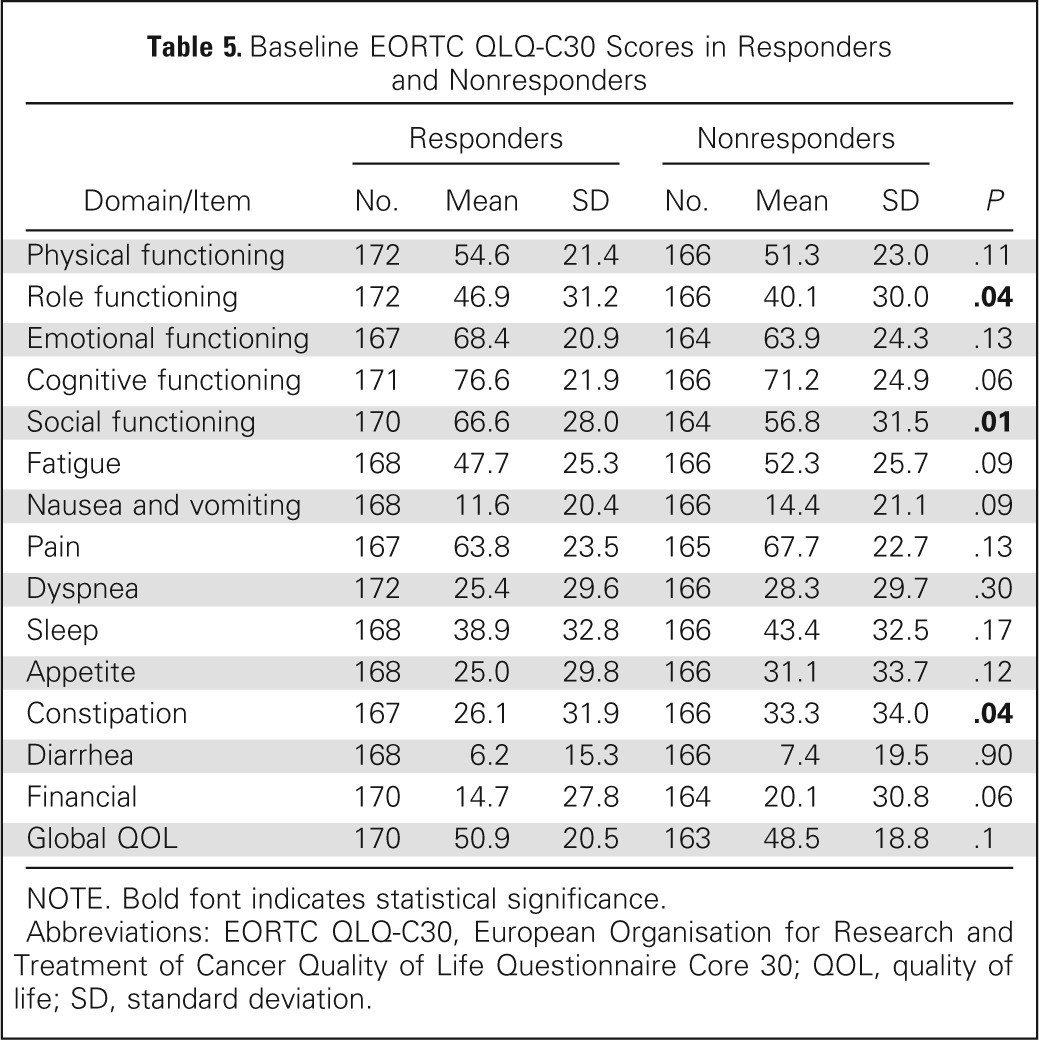

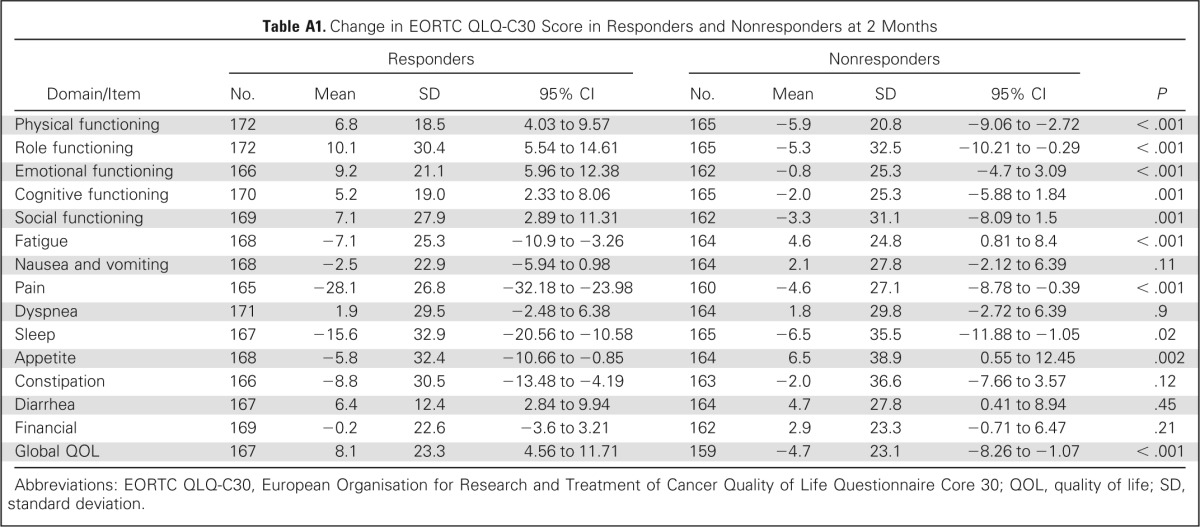

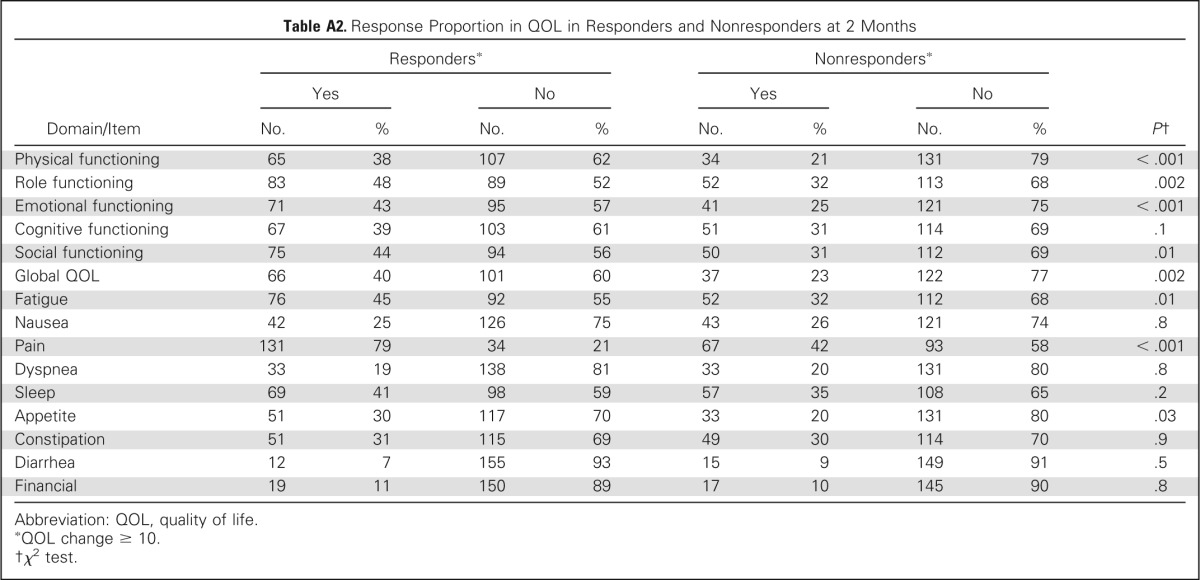

Using the EORTC QLQ-C30, a majority of domains were similar between the two groups at baseline except role functioning, social functioning, and constipation. There was trend of improved cognitive functioning (P = .06) in responders and trends (P = .09) for fatigue, nausea, and financial, which were worse in nonresponders (Table 5). At 2 months, most change scores for items and subscales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 differed between ICE responders and nonresponders. Responders had at least a modest improvement in all items except nausea and vomiting, dyspnea, and financial items, whereas nonresponders improved only in physical and role functioning, sleep, and appetite. Among ICE-responding patients, a large effect size of improvement was seen for the pain item, and a moderate effect size was seen in improvement in sleep and role functioning, whereas none was seen in the nonresponder group (Appendix Table A1; Appendix Fig A2, online only). Comparing the proportion of patients with meaningful change (improvement by ≥ 10 points) between the ICE responders and nonresponders, the items of physical, role, emotional and social functioning, global QOL, fatigue, pain, and appetite were all statistically different in favor of the ICE responders (Appendix Table A2, online only).

Table 5.

Baseline EORTC QLQ-C30 Scores in Responders and Nonresponders

| Domain/Item | Responders |

Nonresponders |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | No. | Mean | SD | ||

| Physical functioning | 172 | 54.6 | 21.4 | 166 | 51.3 | 23.0 | .11 |

| Role functioning | 172 | 46.9 | 31.2 | 166 | 40.1 | 30.0 | .04 |

| Emotional functioning | 167 | 68.4 | 20.9 | 164 | 63.9 | 24.3 | .13 |

| Cognitive functioning | 171 | 76.6 | 21.9 | 166 | 71.2 | 24.9 | .06 |

| Social functioning | 170 | 66.6 | 28.0 | 164 | 56.8 | 31.5 | .01 |

| Fatigue | 168 | 47.7 | 25.3 | 166 | 52.3 | 25.7 | .09 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 168 | 11.6 | 20.4 | 166 | 14.4 | 21.1 | .09 |

| Pain | 167 | 63.8 | 23.5 | 165 | 67.7 | 22.7 | .13 |

| Dyspnea | 172 | 25.4 | 29.6 | 166 | 28.3 | 29.7 | .30 |

| Sleep | 168 | 38.9 | 32.8 | 166 | 43.4 | 32.5 | .17 |

| Appetite | 168 | 25.0 | 29.8 | 166 | 31.1 | 33.7 | .12 |

| Constipation | 167 | 26.1 | 31.9 | 166 | 33.3 | 34.0 | .04 |

| Diarrhea | 168 | 6.2 | 15.3 | 166 | 7.4 | 19.5 | .90 |

| Financial | 170 | 14.7 | 27.8 | 164 | 20.1 | 30.8 | .06 |

| Global QOL | 170 | 50.9 | 20.5 | 163 | 48.5 | 18.8 | .1 |

NOTE. Bold font indicates statistical significance.

Abbreviations: EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30; QOL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation.

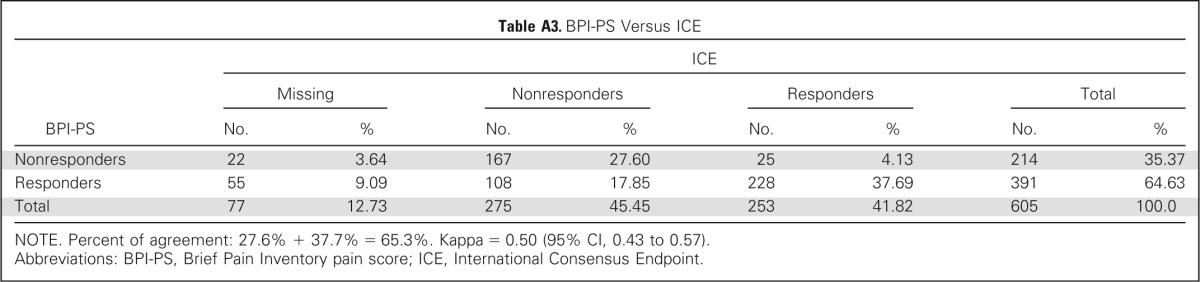

Using the alternate response criteria of BPI-PS only, complete pain score data at baseline and 2-month follow-up were available for analysis in 605 patients. There were 391 patients (65%) in the responder group and 214 (35%) in the nonresponder group. The percent of agreement in response category was 65.3% when compared with consensus end point (Appendix Table A3, online only). Baseline BPI interference scores were similar between the responder and nonresponder groups (Data Supplement). At 2-month follow-up, BPI-PS responders to reirradiation had experienced mean improvement by ≥ 2 points on all items of the BPI-FI except relations with other people and enjoyment of life (Data Supplement). No improvements in BPI-FI scores were seen among BPI-PS nonresponders (Appendix Fig A1, online only). Comparing the proportion of patients with meaningful change (improvement by ≥ 2 points) between BPI-PS responders and nonresponders, all seven BPI-FI items were all statistically different in favor of the responders (Data Supplement).

On the EORTC QLQ-C30, all domains were similar between the two groups at baseline (Data Supplement). At 2-month follow-up, a majority of items and scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 were different between BPI-PS responders and nonresponders (Data Supplement). Responders had at least a modest improvement in role and emotional functioning, pain, sleep, and constipation, whereas nonresponders experienced this only in role functioning and diarrhea. A large effect size of improvement was seen for the pain item, and a moderate effect size of improvement was seen in sleep, but none was seen in the nonresponder group (Appendix Fig A2, online only). Comparing the proportion of meaningful changes between the BPI-PS responders and nonresponders with improvement by ≥ 10 points, the items of physical and role functioning, global QOL, fatigue, pain, and sleep were all statistically different in favor of the responders (Data Supplement).

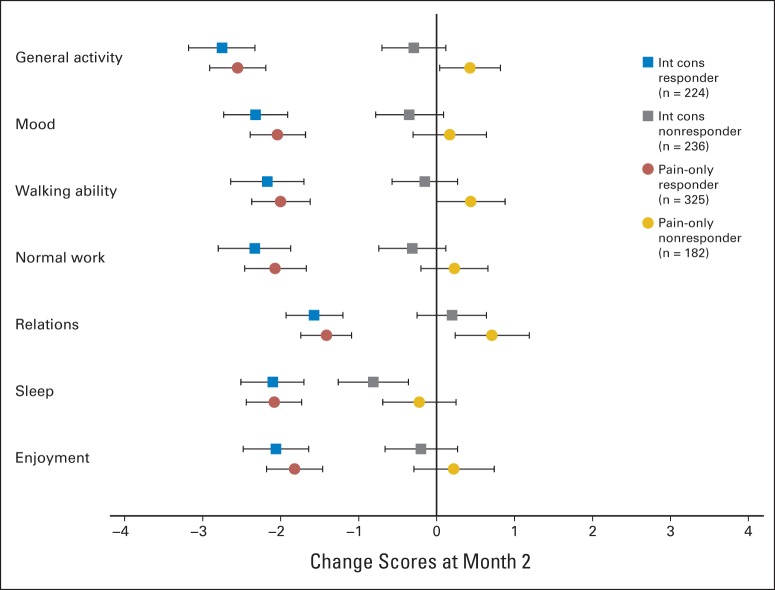

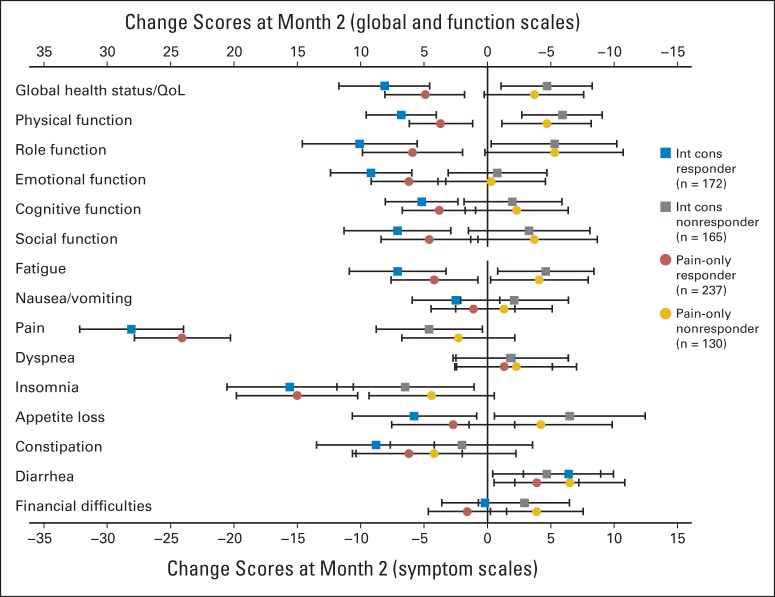

Although mean changes from baseline in BPI-FI and QOL scores were different in responders versus nonresponders regardless of how response was defined, our second objective was to evaluate how these mean change scores differed depending on whether the ICE response definition or BPI-PS definition was used. Appendix Figure A1 (online only) illustrates the point estimates (with 95% CIs) for mean change scores on each BPI-FI domain for responders and nonresponders as determined by using the ICE and BPI-PS. Appendix Figure A2 (online only) shows corresponding data for each QOL function and symptom domain. Statistical comparisons are provided in the Data Supplement. However, Appendix Figures A1 and A2 (online only) illustrate that mean change scores were consistently of greater magnitude in responders using the ICE response definition. For some important domains, such as QOL physical function and global QOL, there was clear discrimination between the magnitude of change scores as a function of response definition.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported that repeat radiation treatment is beneficial for almost half of all evaluable patients with symptomatic bone metastases and that treatment with a single 8-Gy fraction is associated with a noninferior response rate and is less toxic than 20 Gy administered in multiple treatments.3 In this study, response to reirradiation not only resulted in reduction in pain and/or analgesic consumption but also led to superior QOL scores and less functional interference.

In our study, protocol-defined response to reirradiation was associated with clinically significant improvements in general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work, sleep, and enjoyment of life as measured by the BPI-FI scale. No such associations were seen in nonresponders except for sleep. The alternate end point based on BPI-PS score only also provided clear separation of responders from nonresponders, with slightly less discriminative potential in contrast with protocol-defined ICE response schema (Appendix Fig A1, online only).

Prior studies using the BPI questionnaire were reported in first-time radiation treatment. Li et al15 examined 101 patients treated with palliative radiotherapy for painful bone metastases. At 2-month follow-up, all seven functional interference items showed a significant mean reduction when compared with baseline. Of all the items, the four most statistically significant improvements were in general activity, enjoyment of life, sleep, and mood. Relations with others had the least statistically significant improvement among the seven interference items. Comparing responders versus nonresponders at 2 months based on pain response, statistically significant differences were detected for three items: general activity, normal work, and enjoyment of life. Another study by Nguyen et al16 used the BPI to determine functional interference changes at 2 months after radiation treatment in 212 patients with bone metastases. All seven interference items improved after radiotherapy. With respect to responders, pain relief correlated significantly with all functional interference improvements except sleep. Wu et al17 also reported on 109 patients who completed the BPI 4 to 6 weeks after palliative radiotherapy for painful bone metastases. A significant reduction for all seven functional interference items was seen after treatment, with the greatest improvement in general activity.

In an earlier randomized trial of dose fractionation schedules, pain relief and QOL after initial radiotherapy for bone metastases were reported.18 The physicians completed Spitzer's QOL index, including five items concerning activity, daily living, health, support, and outlook, which most closely reflects patient status. Patients also completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression questionnaire to screen for clinically significant levels of anxiety and depression. Prevalence of both anxiety and depression diminished after treatment. QOL as measured by the Spitzer index also improved after treatment. Zeng et al19 analyzed QOL after initial palliative radiotherapy in patients with bone metastases and found that responders to treatment had significantly better physical functioning, role functioning, and pain when compared with nonresponders.

In our study, a large effect size improvement in pain was seen, and a moderate effect size improvement in sleep and role functioning was seen for the protocol-defined responders to reirradiation. No such improvements were seen in the nonresponder group on the EORTC QLQ-C30. Symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, dyspnea, constipation, and diarrhea were not different at 2-month follow-up between the two groups, likely because these symptoms are related to radiation treatment and usually resolve by the 2-month follow-up visit.3

We previously reported that repeat irradiation for painful osseous metastases resulted in improved pain response. In this analysis, we augmented this by demonstrating that the response to pain resulted in clinically meaningful improvements in QOL. This study also provides clinical data that validate the end points recommended by the international bone metastases consensus working party for clinical trials in bone metastases,5 with respect to the evaluative and discriminative properties of the response criteria. However, missing opioid intake data, especially during follow-up, introduce uncertainty in the estimation of treatment response.20 The alternative response criterion by the BPI-PS only, with the cutoff of 2 of 10 points as a measure of response, was confirmed in another cancer pain validation study.21 Because analgesic data are not needed for this end point, more participants from our study were evaluable for response, thus increasing the effective sample size. However, this response criterion does not account for the confounding analgesic effect of opioids and apparently overestimates response to repeat irradiation (65% v 48%).20 In contrast, the consensus-recommended end point, although accounting for the confounding effects of opioids, may underestimate the true proportion of patients who experience pain relief. In the two forest plots for most domains, the point estimate of mean improved score is greater using the consensus criteria. For several important functional domains, the point estimate of the BPI-PS–only defined response is barely within the confidence limits of the ICE-defined response, favoring the latter approach (Appendix Figs A1 and A2, online only). In choosing a treatment end point for a clinical trial in chronic pain, a tradeoff exists in terms of the ease of data collection and the potential error of ascribing outcome effect to one intervention in the presence of cointerventions. Different end points may also result in opposite conclusions regarding the trial interpretation, as has been seen in previous trials.5

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that responders to reirradiation experience clinically important improvements in functional interference and QOL scores. Patients should be offered re-treatment for painful bone metastases in the hope of reducing pain severity as well as improving QOL and pain interference.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank all investigators, clinical research assistants, and patients for participation in this study coordinated by the NCIC Clinical Trials Group.

Appendix

Table A1.

Change in EORTC QLQ-C30 Score in Responders and Nonresponders at 2 Months

| Domain/Item | Responders |

Nonresponders |

P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | 95% CI | No. | Mean | SD | 95% CI | ||

| Physical functioning | 172 | 6.8 | 18.5 | 4.03 to 9.57 | 165 | −5.9 | 20.8 | −9.06 to −2.72 | < .001 |

| Role functioning | 172 | 10.1 | 30.4 | 5.54 to 14.61 | 165 | −5.3 | 32.5 | −10.21 to −0.29 | < .001 |

| Emotional functioning | 166 | 9.2 | 21.1 | 5.96 to 12.38 | 162 | −0.8 | 25.3 | −4.7 to 3.09 | < .001 |

| Cognitive functioning | 170 | 5.2 | 19.0 | 2.33 to 8.06 | 165 | −2.0 | 25.3 | −5.88 to 1.84 | .001 |

| Social functioning | 169 | 7.1 | 27.9 | 2.89 to 11.31 | 162 | −3.3 | 31.1 | −8.09 to 1.5 | .001 |

| Fatigue | 168 | −7.1 | 25.3 | −10.9 to −3.26 | 164 | 4.6 | 24.8 | 0.81 to 8.4 | < .001 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 168 | −2.5 | 22.9 | −5.94 to 0.98 | 164 | 2.1 | 27.8 | −2.12 to 6.39 | .11 |

| Pain | 165 | −28.1 | 26.8 | −32.18 to −23.98 | 160 | −4.6 | 27.1 | −8.78 to −0.39 | < .001 |

| Dyspnea | 171 | 1.9 | 29.5 | −2.48 to 6.38 | 164 | 1.8 | 29.8 | −2.72 to 6.39 | .9 |

| Sleep | 167 | −15.6 | 32.9 | −20.56 to −10.58 | 165 | −6.5 | 35.5 | −11.88 to −1.05 | .02 |

| Appetite | 168 | −5.8 | 32.4 | −10.66 to −0.85 | 164 | 6.5 | 38.9 | 0.55 to 12.45 | .002 |

| Constipation | 166 | −8.8 | 30.5 | −13.48 to −4.19 | 163 | −2.0 | 36.6 | −7.66 to 3.57 | .12 |

| Diarrhea | 167 | 6.4 | 12.4 | 2.84 to 9.94 | 164 | 4.7 | 27.8 | 0.41 to 8.94 | .45 |

| Financial | 169 | −0.2 | 22.6 | −3.6 to 3.21 | 162 | 2.9 | 23.3 | −0.71 to 6.47 | .21 |

| Global QOL | 167 | 8.1 | 23.3 | 4.56 to 11.71 | 159 | −4.7 | 23.1 | −8.26 to −1.07 | < .001 |

Abbreviations: EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30; QOL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation.

Table A2.

Response Proportion in QOL in Responders and Nonresponders at 2 Months

| Domain/Item | Responders* |

Nonresponders* |

P† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Physical functioning | 65 | 38 | 107 | 62 | 34 | 21 | 131 | 79 | < .001 |

| Role functioning | 83 | 48 | 89 | 52 | 52 | 32 | 113 | 68 | .002 |

| Emotional functioning | 71 | 43 | 95 | 57 | 41 | 25 | 121 | 75 | < .001 |

| Cognitive functioning | 67 | 39 | 103 | 61 | 51 | 31 | 114 | 69 | .1 |

| Social functioning | 75 | 44 | 94 | 56 | 50 | 31 | 112 | 69 | .01 |

| Global QOL | 66 | 40 | 101 | 60 | 37 | 23 | 122 | 77 | .002 |

| Fatigue | 76 | 45 | 92 | 55 | 52 | 32 | 112 | 68 | .01 |

| Nausea | 42 | 25 | 126 | 75 | 43 | 26 | 121 | 74 | .8 |

| Pain | 131 | 79 | 34 | 21 | 67 | 42 | 93 | 58 | < .001 |

| Dyspnea | 33 | 19 | 138 | 81 | 33 | 20 | 131 | 80 | .8 |

| Sleep | 69 | 41 | 98 | 59 | 57 | 35 | 108 | 65 | .2 |

| Appetite | 51 | 30 | 117 | 70 | 33 | 20 | 131 | 80 | .03 |

| Constipation | 51 | 31 | 115 | 69 | 49 | 30 | 114 | 70 | .9 |

| Diarrhea | 12 | 7 | 155 | 93 | 15 | 9 | 149 | 91 | .5 |

| Financial | 19 | 11 | 150 | 89 | 17 | 10 | 145 | 90 | .8 |

Abbreviation: QOL, quality of life.

QOL change ≥ 10.

χ2 test.

Table A3.

BPI-PS Versus ICE

| BPI-PS | ICE |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing |

Nonresponders |

Responders |

Total |

|||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Nonresponders | 22 | 3.64 | 167 | 27.60 | 25 | 4.13 | 214 | 35.37 |

| Responders | 55 | 9.09 | 108 | 17.85 | 228 | 37.69 | 391 | 64.63 |

| Total | 77 | 12.73 | 275 | 45.45 | 253 | 41.82 | 605 | 100.0 |

NOTE. Percent of agreement: 27.6% + 37.7% = 65.3%. Kappa = 0.50 (95% CI, 0.43 to 0.57).

Abbreviations: BPI-PS, Brief Pain Inventory pain score; ICE, International Consensus Endpoint.

Fig A1.

Average change scores after radiotherapy (and 95% CIs) for responders versus nonresponders defined per protocol (international consensus [int cons]) and by Brief Pain Inventory pain score pain-only methods. Negative change score represents average improvement for given item.

Fig A2.

Average quality of life (QoL) change scores (and 95% CIs) after radiotherapy for responders versus nonresponders based on two methods of defining treatment response: international consensus (int cons) and Brief Pain Inventory pain score pain-only methods. Change scores to left of vertical reference line denote improvement.

Footnotes

Listen to the podcast by Dr Salama at www.jco.org/podcasts

Supported by NCIC Clinical Trials Group programmatic grants from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (Canada); by Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Grant No. U10 CA21661 and Community Clinical Oncology Program Grant No. U10 CA37422 from the National Cancer Institute (United States); by a grant for international infrastructure support from Cancer Council Australia and a special purposes fund research grant from Royal Adelaide Hospital (Australia and New Zealand); by the Dutch Cancer Society Grant No. CKTO 2004-06, which funded national data management for Dutch patients (the Netherlands); and by Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris (France).

Clinical trial information: NCT00080912.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Edward Chow, Ralph M. Meyer, Bingshu E. Chen, Yvette M. van der Linden, Daniel Roos, William F. Hartsell, Peter Hoskin, Jackson S.Y. Wu, William F. Demas, Rebecca K.S. Wong, Michael Brundage

Financial support: Ralph M. Meyer

Administrative support: Ralph M. Meyer, Carolyn F. Wilson

Provision of study materials or patients: Edward Chow, Ralph M. Meyer, Yvette M. van der Linden, Daniel Roos, William F. Hartsell, Peter Hoskin, Jackson S.Y. Wu, Abdenour Nabid, Caroline J.A. Tissing-Tan, Bing Oei, Scott Babington, William F. Demas, Rebecca K.S. Wong

Collection and assembly of data: Edward Chow, Ralph M. Meyer, Bingshu E. Chen, Yvette M. van der Linden, Daniel Roos, William F. Hartsell, Peter Hoskin, Jackson S.Y. Wu, Abdenour Nabid, Caroline J.A. Tissing-Tan, Bing Oei, Scott Babington, William F. Demas, Carolyn F. Wilson, Rebecca K.S. Wong

Data analysis and interpretation: Edward Chow, Ralph M. Meyer, Bingshu E. Chen, Yvette M. van der Linden, Daniel Roos, William F. Hartsell, Peter Hoskin, Jackson S.Y. Wu, William F. Demas, Rebecca K.S. Wong, Michael Brundage

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Impact of Reirradiation of Painful Osseous Metastases on Quality of Life and Function: A Secondary Analysis of the NCIC CTG SC.20 Randomized Trial

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Edward Chow

No relationship to disclose

Ralph M. Meyer

No relationship to disclose

Bingshu E. Chen

No relationship to disclose

Yvette M. van der Linden

No relationship to disclose

Daniel Roos

No relationship to disclose

William F. Hartsell

Honoraria: IBA

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: .decimal

Peter Hoskin

No relationship to disclose

Jackson S.Y. Wu

No relationship to disclose

Abdenour Nabid

Consulting or Advisory Role: Sanofi

Speakers' Bureau: Sanofi

Research Funding: AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi

Caroline J.A. Tissing-Tan

Employment: Sirtex Medical (I)

Bing Oei

No relationship to disclose

Scott Babington

No relationship to disclose

William F. Demas

Consulting or Advisory Role: Guidepoint Global

Carolyn F. Wilson

No relationship to disclose

Rebecca K.S. Wong

No relationship to disclose

Michael Brundage

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Chow E, Zeng L, Salvo N, et al. Update on the systematic review of palliative radiotherapy trials for bone metastases. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2012;24:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong E, Hoskin P, Bedard G, et al. Re-irradiation for painful bone metastases: A systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow E, van der Linden YM, Roos D, et al. Single versus multiple fractions of repeat radiation for painful bone metastases: A randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:164–171. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70556-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JS, Bezjak A, Chow E, et al. Primary treatment endpoint following palliative radiotherapy for painful bone metastases: Need for a consensus definition? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2002;14:70–77. doi: 10.1053/clon.2001.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow E, Wu JS, Hoskin P, et al. International consensus on palliative radiotherapy endpoints for future clinical trials in bone metastases. Radiother Oncol. 2002;64:275–280. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow E, Hoskin P, Mitera G, et al. Update of the international consensus on palliative radiotherapy endpoints for future clinical trials in bone metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1730–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Linden YM, Lok JJ, Steenland E, et al. Single fraction radiotherapy is efficacious: A further analysis of the Dutch bone metastasis study controlling for the influence of retreatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:528–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, et al. Randomized trial of short- versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:798–804. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bottomley A, Flechtner H, Efficace F, et al. Health related quality of life outcomes in cancer clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1697–1709. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong K, Zeng L, Zhang L, et al. Minimal clinically important differences in the brief pain inventory in patients with bone metastases. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1893–1899. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1731-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain. 1983;17:197–210. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilcoxon F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biometrics. 1945;1:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li K, Chow E, Chiu H, et al. Effectiveness of palliative radiotherapy in the treatment of bone metastases employing the Brief Pain Inventory. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;2:19–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen J, Chow E, Zeng L, et al. Palliative response and functional interference outcomes using the Brief Pain Inventory for spinal bony metastases treated with conventional radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2011;23:485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.01.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu JS, Monk G, Clark T, et al. Palliative radiotherapy improves pain and reduces functional interference in patients with painful bone metastases: A quality assurance study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2006;18:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaze MN, Kelly CG, Kerr GR, et al. Pain relief and quality of life following radiotherapy for bone metastases: A randomised trial of two fractionation schedules. Radiother Oncol. 1997;45:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng L, Chow E, Bedard G, et al. Quality of life after palliative radiation therapy for patients with painful bone metastases: Results of an international study validating the EORTC QLQ-BM22. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:e337–e342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chow E, Davis L, Holden L, et al. A comparison of radiotherapy outcomes of bone metastases employing international consensus endpoints and traditional endpoints. Support Cancer Ther. 2004;1:173–178. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrar JT, Berlin JA, Strom BL. Clinically important changes in acute pain outcome measures: A validation study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:406–411. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.