Background: Expression of Drosophila melanogaster nucleoside kinase (Dm-dNK) in mice causes deoxyribonucleotide (dNTP) pool imbalances.

Results: Long term Dm-dNK expression rescued thymidine kinase 2 (Tk2)-deficient mice without lethal side effects.

Conclusion: Dm-dNK is a candidate to treat TK2 deficiency.

Significance: The results highlight mechanisms involved in the in vivo regulation of dNTP pools.

Keywords: Gene Therapy, Mitochondrial Disease, Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), Nucleoside/Nucleotide Metabolism, Nucleoside/Nucleotide Transport, Thymidine Kinase 2

Abstract

Mitochondrial DNA depletion caused by thymidine kinase 2 (TK2) deficiency can be compensated by a nucleoside kinase from Drosophila melanogaster (Dm-dNK) in mice. We show that transgene expression of Dm-dNK in Tk2 knock-out (Tk2−/−) mice extended the life span of Tk2−/− mice from 3 weeks to at least 20 months. The Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice maintained normal mitochondrial DNA levels throughout the observation time. A significant difference in total body weight due to the reduction of subcutaneous and visceral fat in the Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice was the only visible difference compared with control mice. This indicates an effect on fat metabolism mediated through residual Tk2 deficiency because Dm-dNK expression was low in both liver and fat tissues. Dm-dNK expression led to increased dNTP pools and an increase in the catabolism of purine and pyrimidine nucleotides but these alterations did not apparently affect the mice during the 20 months of observation. In conclusion, Dm-dNK expression in the cell nucleus expanded the total dNTP pools to levels required for efficient mitochondrial DNA synthesis, thereby compensated the Tk2 deficiency, during a normal life span of the mice. The Dm-dNK+/− mouse serves as a model for nucleoside gene or enzyme substitutions, nucleotide imbalances, and dNTP alterations in different tissues.

Introduction

Nucleotides required for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)2 are supplied by de novo synthesis of nucleotides in the cytosol and subsequent transport into the mitochondria and/or by salvage of deoxyribonucleosides within the mitochondria by the enzymes thymidine kinase 2 (TK2) and deoxyguanosine kinase (DGUOK). TK2 and DGUOK are mitochondrial enzymes phosphorylating deoxythymidine (dThd), deoxyuridine (dUrd) and deoxycytidine (dCyt), and deoxyguanosine (dGuo) and deoxyadenosine (dAdo), respectively. Deletions or mutations in the TK2 gene has been associated with myopathic and encephalomyopathic forms of mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome (1, 2). Tk2 knock-out (Tk2−/−) mice survive for only 2–4 weeks and die with signs of severe mtDNA depletion in various tissues, such as skeletal muscle, brain, liver, heart, and spleen, and show pronounced loss of hypodermal fat (3). The mtDNA depletion in these mice is believed to be a result of depletion of the mitochondrial dTTP pool, caused by the lack of the salvage pathway enzyme that contributes to most of the dTTP in non-replicating cells. In a strategy to reverse the phenotype of Tk2 deficiency, and to compensate for the loss of Tk2, we used a nucleoside kinase from Drosophila melanogaster (Dm-dNK) that phosphorylates all four deoxyribonucleosides with high catalytic activity and that has been previously expressed at high levels in mammalian cells (4–7). Expression of Dm-dNK was shown to compensate for the loss of dTTP and reverse the mtDNA depletion in Tk2-deficient mice (8). Dm-dNK expressing Tk2 knock-out mice (Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/−) appeared as wild-type (wt) mice with respect to growth and behavior for a period of 6 months. The Dm-dNK expressing mice had >100-fold higher dTTP levels compared with the wt mice but this increase did not affect the fidelity of DNA synthesis for up to 6 months (8).

The present study was initiated to investigate the total life span of the Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice as well as the long term effects of Dm-dNK expression. The results show that Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− and Dm-dNK+/− mice survive as long as wt mice and maintain normal mtDNA levels until they are 20 months. The Dm-dNK transgene was constitutively expressed and able to compensate for the dTTP loss caused by TK2 deficiency in most tissues. Gene expression analysis revealed increased mRNA levels of the nucleoside catabolizing enzymes thymidine phosphorylase (Tymp) and purine nucleoside phosphorylase (Pnp) in the Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice. The only phenotypic differences observed were that the Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice were smaller than the wt and Dm-dNK+/− mice and had reduced subcutaneous and visceral fat.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

Three groups of mice were used in this study: C57BL/6 (wt), Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/−. The Dm-dNK+/− transgene was designed with a His6 tag, driven by the expression of the CMV promoter. The transgene was injected into fertilized oocytes of female C57BL/6 mice. The Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice were obtained by inter-crossing and genotyped as previously described (8) The mice were further classified in three age groups: 6, 12, and 18–20 months. All animal experiments were compliant with the guidelines of the local ethical committee (S104-09, S135-11).

Generation of Antibody against Dm-dNK

An anti-Dm-dNK polyclonal antibody was developed in rabbit (Agrisera, Vännäs, Sweden) and purified using HiTrap NHS-activated HP affinity columns (GE Healthcare). The antibody was re-purified using affinity columns embedded with total protein extracts from tissues of Dm-dNK−/− (wt) mice.

Dm-dNK Protein Expression

Total protein was extracted from the indicated tissues using RIPA buffer and Western blot was performed as previously described (8). Presence of the Dm-dNK protein was detected using the polyclonal rabbit anti-Dm-dNK antibody (1:3000) and donkey anti-rabbit IgG linked to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:5000). ECL (GE Healthcare) was used as a substrate for the HRP. The membranes were stripped using RestoreTM PLUS Western blot stripping buffer (Thermo Scientific) and re-probed with mouse anti-β-actin antibody (1:3000; Sigma) and HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (1:3000; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and developed using ECL.

Enzyme Activity Assays

Tissues were homogenized (Qiagen tissue ruptor) and suspended in extraction buffer as previously described (7). The lysate was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected and stored at −80 °C for further use. Protein concentrations were measured with Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a concentration standard. The enzymatic assays were performed in a 50-μl reaction mixture as described (8) with 3 μm [methyl-3H]thymidine (2 Ci/mmol; Moravek, Brea, CA), and 7 μm unlabeled thymidine, and the radioactivity was quantified by scintillation counting.

Preparation of Mitochondria

Mitochondria from fresh liver of wt and Dm-dNK+/− mice were extracted as described (9). Briefly, fresh whole liver was rapidly excised, washed twice in ice-cold PBS, and transferred to cold isolation buffer (210 mm mannitol, 70 mm sucrose, 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.2 mm EGTA, and 0.5% BSA). The liver was cut into small pieces and homogenized using a glass homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 2 min and the supernatant was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 2 min. The pellet was washed with 1 ml of isolation buffer and centrifuged again at 13,000 × g for 2 min. The pellet was re-suspended in 1 ml of isolation buffer (without BSA) and 100 μl was saved for determination of protein. The suspension was centrifuged again at 13,000 × g for 2 min and the pellet was stored in −80 °C for dNTP extraction.

Extraction of dNTPs

dNTPs were extracted from skeletal muscle, as previously described (8), and mitochondria (9). Briefly skeletal muscle samples were homogenized on ice using a Qiagen tissue-ruptor in 10 volumes (w/v) of cold MTSE buffer and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 3 min. The supernatants were precipitated with 60% methanol in −20 °C for 1–3 h and centrifuged at 20,670 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was heated in a boiling water bath for 3 min and centrifuged at 20,670 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was evaporated to dryness and the pellet was re-suspended in 0.2 ml of distilled water.

Similarly, dNTPs from the mitochondrial pellet was extracted with 2 ml of 60% methanol as described above. The dried pellet was re-suspended in 0.15 ml of distilled water and stored in −80 °C until further use.

dNTP Assay

For whole cell extracts from skeletal muscle, dNTP pools were quantified as described (10, 11). Briefly, 100-μl reaction volumes were generated with 10 μl of sample or standard and 90 μl of reaction buffer containing 40 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm DTT, 0.25 μm of specific oligonucleotide template, 0.25 μm [2,8-3H]dATP (15.2 Ci/mmol for dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP determinations; Moravek) or [5-3H]dCTP (23.5 Ci/mmol for dATP determinations; Moravek) and 0.2 units of Klenow DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs). After a 45-min incubation at 37 °C, 10 μl of the reaction mixture was spotted on Whatman DE-81 filter discs. After drying, the filters were washed (3 × 10 min) in 5% Na2HPO4, once in distilled water and once in 95% ethanol (10 min each). The filters are completely dried, and the retained radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting.

dNTPs from the mitochondria was extracted as described (9). Briefly, a 20-μl reaction volume containing 10 μl of sample or standard and 10 μl of reaction buffer was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. 19 μl of reaction mixture was then spotted on Whatman DE-81 filter discs and the dNTP pools were measured as described above.

The oligonucleotide templates and primers for measurement of dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP pools are as described (10) with a slight modification in the dATP template as described in Table 1 (Sigma). All experiments were performed in duplicates and dNTP pools were determined in picomole of dNTP/mg of tissue (for whole cell extracts) and in picomole dNTP/mg of mitochondria (for mitochondrial extracts).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide templates and primer for dNTP pool determination

| dNTP | Sequence |

|---|---|

| dTTP | TTATTATTATTATTATTAGGCGGTGGAGGCGG |

| dCTP | TTTGTTTGTTTGTTTGTTTGGGCGGTGGAGGCGG |

| dGTP | TTTCTTTCTTTCTTTCTTTCGGCGGTGGAGGCGG |

| dATP | GGGTGGGTGGGTGGGTGGGTGGCGGTGGAGGCGG |

| Primer | CCGCCTCCACCGCC |

Gene Expression Analysis

The mRNA levels of various genes were quantified. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and cDNA was synthesized using the high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The expression analysis of all genes was done with specific primers in the ABI 7500 Fast machine (Applied Biosystems), using the endogenous GAPDH gene as reference gene for quantitative PCR normalization. KAPA SYBR Fast qPCR kit (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA) was used to analyze genes involved in deoxyribonucleotide catabolism and TaqMan Fast Universal PCR mix (Invitrogen) with specific probes (MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany) were used to analyze genes involved in deoxyribonucleotide anabolism. The primers and probes for all the genes studied are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

TABLE 2.

Primer sequences

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Gene expression analysis | ||

| Tk1 | TCA AGA TGC TGC CGA AAG C | CCA ACG AGG GCA AGA CAG TAA |

| Tk2 | AGC ATG GTG AGC TGC ACG TA | CCA TGG CCA TAA CCC TCT GA |

| dCk | CCT CAG AGG CTT GCT TTA GGA TAT | GGA CCC GCA TCA AGA AGA TC |

| Dguok | GCT CTG CAT TGA AGG CAA CA | CCG GGT GAG TTT TCA TGA GTA AC |

| Rrm2 | GCT TAT TAG CAG AGA CGA GGG TTT | TCC GCT GGC TTG TGT ACC A |

| Rrm2b | GAC GAA CCG TCG GGA ACT C | TGG GCG ACC CGG AAA |

| Gapdh | TGT GTC CGT CGT GGA TCT GA | CCT GCT TCA CCA CCT TCT TGA |

| Tymp | TAC CCT GGA GGT GGA AGA AG | GCC TCC TAG CCT AAT GAC CA |

| Pnp | AAG TGG CTT CTG CAA CAC AC | GTG ACC TTG CAC TGT GCT TT |

| Ada | TTG AGG TGT TGG AGC TGT GT | TTC TTT ACT GCG CCC TCA TA |

| Cda | GAT CTT CTC TGG GTG CAA CA | ATG GCA ATA GCC CTG AAA TC |

| Gda | TGA GCC ACC ATG AGT TCT TC | TCC AGC AAA GGC ATA CTG AG |

| Upp1 | TTT GGA GAC GTG AAG TTT GTG | GGG ATA TTC CTT CCC TGG AT |

| Upp2 | TGA GAG CTG CTG TGG TCT GT | GAT TAG AAG CTG TGG CCG TT |

| Upb1 | AAT CAC TGC TTC ACC TGT GC | CAT GGT GAG CTT TCT TTC CA |

| Xdh | ACA GCA GGA AGG GTG AGT TT | TCA CCT TGG CAA TGT CAT CT |

| Samhd1 | TTG CCA GAG ACT GTC ACC AT | CGA ACA AAT GTG CTT CAC CT |

| mtDNA copy number | ||

| Rpph1 | GGA GAG TAG TCT GAA TTG GGT TAT GAG | CAG CAG TGC GAG TTC AAT GG |

| mt-Nd1 | TCG ACC TGA CAG AAG GAG AAT CA | GGG CCG GCT GCG TAT T |

| Mutation analysis | ||

| mt-Cytb | TTTGAGCTCTTTCTACACAGCATTCAACTG | TTTGAGCTCGTCTGGGTCTCCTAGTATG |

| Hprt | TTTGAGCTCGGCTTCCTCCTCAGACCG | TTTACTAGTGGACTCCTCGTATTTGCAGA |

TABLE 3.

Probe sequences

| Gene | Probe |

|---|---|

| Gene expression analysis | |

| Tk1 | FAM-TCC CAT CCA GCG CTG CCA CA-TAMRA |

| Tk2 | FAM-AGG CCC CAT CGG CTG GCA TC-TAMRA |

| dCk | FAM-ACA AAC GTT GAC TTC CCA GCA GCG A-TAMRA |

| Dguok | FAM-CGC TGT GGG CAA ATC CAC CTT TGT-TAMRA |

| Rrm2 | FAM-CAC TGT GAC TTT GCC TGC CTG ATG TTC A-TAMRA |

| Rrm2b | FAM-CCT CAC CAC ATT TTC TTC TGT CTC CGA ACA-TAMRA |

| Gapdh | FAM-TGC CGC CTG GAG AAA CCT GCC-TAMRA |

| mtDNA copy number | |

| Rpph1 | FAM-CCGGGAGGTGCCTC-TAMRA |

| mt-Nd1 | FAM-AATTAGTATCAGGGTTTAACG-TAMRA |

Quantification of mtDNA Copy Number

mtDNA copy number was measured by quantitative PCR as previously described (8). Briefly, total genomic DNA was purified from mouse tissues using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen). 10–20 ng of DNA was used in each reaction. For each DNA sample, the mitochondrial encoded NADH dehydrogenase 1 (mt-Nd1) and nuclear-encoded ribonuclease P RNA component H1 (Rpph1) were quantified separately using primers and probes designed for this purpose (Tables 2 and 3).

Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Point Mutation Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from skeletal muscle of 12-month-old mice and cDNA was synthesized as described before. Using cDNA as template 741-bp fragments of mouse nuclear Hprt exons were amplified by high-fidelity PCR. Total DNA was extracted from skeletal muscle of 12-month-old mice and fragments of the mt-Cytb gene (883 bp) were amplified by high fidelity PCR.

The PCR products (of both genes) were cloned into pGEM®-T vector (Promega) after A-tailing according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmids of multiple clones obtained were sequenced, and point mutations and mutation rates were calculated as previously described (8). The primers for the genes are listed in Table 2.

Histopathology

Selected tissue samples from two mice per genotype were fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde and transferred to 70% ethanol after 24 h. After routine processing and paraffin embedding, 4-μm thick sections were mounted on glass slides, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and viewed using brightfield microscopy.

Immunohistochemistry

The presence of the Dm-dNK was evaluated by immunohistochemistry with the use of a polyclonal antibody raised in mouse against histidine (His6 tag of the Dm-dNK protein; mouse pAb) as described in Ref. 12. Briefly, the slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated and antigen unmasking was performed using 0.01 m citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave. After cooling, tissue sections were treated with 3% H2O2 for 10 min, and washed in 1 time in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.6). The slides were incubated with primary antibody, mouse anti-His tag (1:100), overnight at 4 °C using the vector® M.O.M.TM immunostaining kit (Vector Laboratories, Stockholm, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions and detected using a diaminobenzidine staining reaction.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Small pieces from different tissues were fixed in fixation buffer, 2% glutaraldehyde, 0.5% paraformaldehyde, 0.1 m sodium cacodylate, 0.1 m sucrose, and 3 mm CaCl2 (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 30 min, and stored in the fixative at 4 °C. Specimens were rinsed in a buffer containing 150 mm sodium cacodylate and 3 mm CaCl2 (pH 7.4), postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide, 70 mm sodium cacodylate, 1.5 mm CaCl2 (pH 7.4) at 4 °C for 2 h, dehydrated in ethanol followed by acetone, and embedded in LX-112 (Ladd, Burlington, VT). Semi-thin sections (0.5 μm) were cut and stained with toluidine blue for light microscopy. Ultra-thin sections (50–70 nm) from selected areas were then cut and examined in a Tecnai 10 transmission electron microscope (FEI company, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at 80 kV. Digital images were taken using a Veleta camera (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions, GmbH, Münster, Germany) (13). Volume density (Vv) measurements of mitochondria were performed as described earlier (14).

Statistical Analysis

All experimental data are represented as mean ± S.E. (shown as error bars). Student's t test was used to analyze the differences between the means and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Life Span, Phenotype and Enzyme Activity of Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− Mice at 6–20 Months of Age

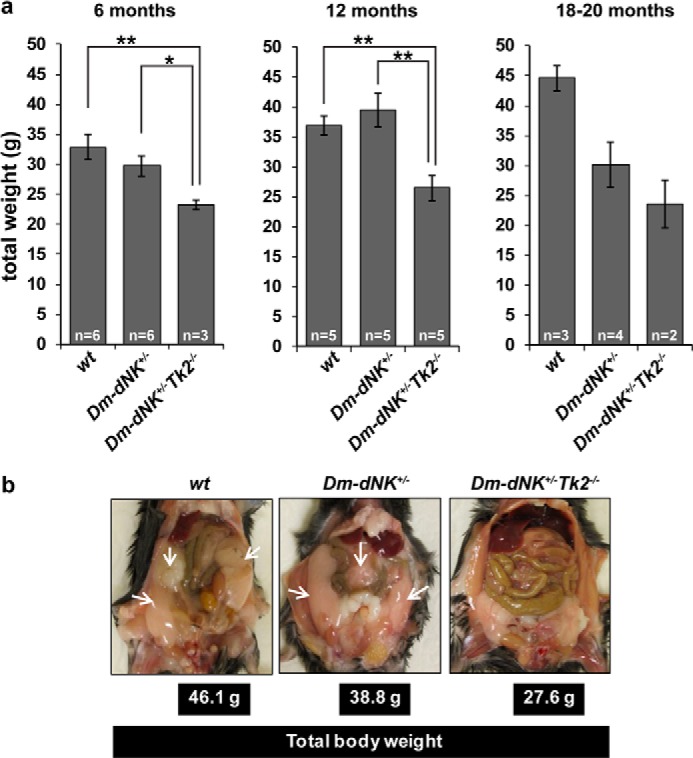

The life span of Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice was similar to that of wt and Dm-dNK+/− mice. All groups were similar with regards to behavior up to 18 months and were not kept longer than 20 months. Total body weight of the mice were analyzed at 6, 12, and 18–20 months. The Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice had significantly lower total body weight as compared with wt and Dm-dNK+/− (*, p < 0.05) mice at all ages (Fig. 1a). The lower body weight was a result of less visceral and subcutaneous fat in the Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice as compared with wt and Dm-dNK+/− mice and this was observed in mice of all ages analyzed (Fig. 1b).

FIGURE 1.

Total body weights of Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice. a, comparison of total body weights of wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice that are 6, 12, and 18–20 months. All data are represented as mean ± S.E. b, visceral fat content (white arrows) in wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice.

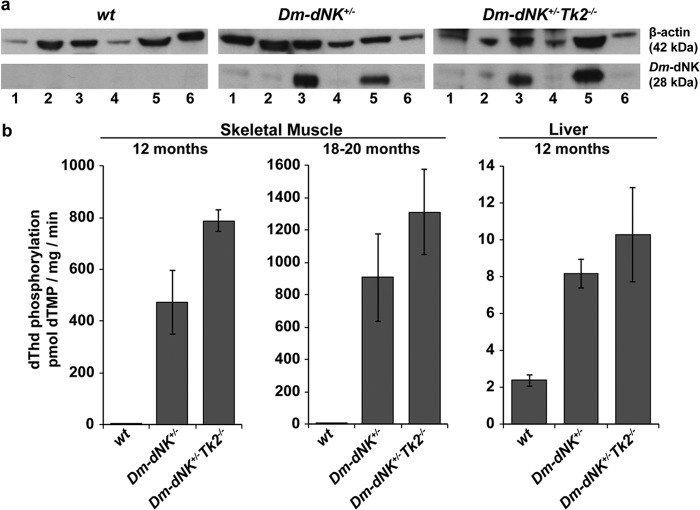

The Dm-dNK protein (28 kDa) was detected at high levels in skeletal muscle and kidney of 6-month-old Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− samples, and at lower levels in brain, liver, and white and brown adipose tissue (WAT and BAT), using Western blot analysis (Fig. 2a).

FIGURE 2.

Dm-dNK expression and activity. a, Western blot of Dm-dNK protein (28 kDa) in lanes 1, brown adipose tissue; 2, brain; 3, kidney; 4, liver; 5, skeletal muscle, and 6, WAT of wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice (6 months). Loading control was β-actin (42 kDa). b, dThd phosphorylating activity of wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice; skeletal muscle of 12-month (n = 3 each) and 18–20-month-old (n = 5 each) mice, and, liver of 12-month-old mice (n = 3 each). All data are represented as mean ± S.E.

The dThd phosphorylating activity was observed to be >100-fold higher in skeletal muscle of 12- and 18–20-month-old Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice as compared with wt mice. In the liver the dThd phosphorylating activity was 3–4 times higher in the Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice than in wt mice (Fig. 2b).

Levels of mtDNA, dNTP Pools, and Expression Profiles of Genes Involved in Nucleotide Metabolism

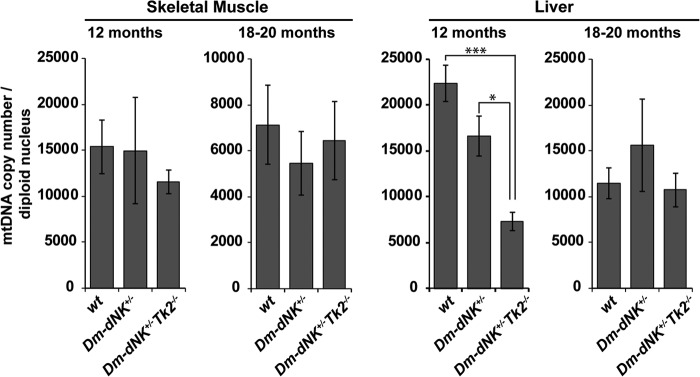

The mtDNA copy number was measured in liver and skeletal muscle samples from 12- and 18-month-old mice (Fig. 3). No significant difference was observed between skeletal muscle of the wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− samples. A decrease in mtDNA copy number in liver of Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice was observed at 12 months of age (*, p < 0.05). At 18 months there was a general decrease of mtDNA in all samples but no significant difference between the mouse lines.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of mtDNA copy number between wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice. mtDNA copy number in liver and skeletal muscle of 12- and 18–20-month-old mice (n = 3–5 each). All data are represented as mean ± S.E., p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.005 (***).

Intracellular dNTP pools were measured in whole cell extracts of skeletal muscle of 12-month-old wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice (Table 4). dTTP levels were >100-fold higher in Dm-dNK+/−TK2−/− mice as compared with wt mice (***, p < 0.005). Similarly dCTP, dGTP, and dATP levels were, respectively, 5-, 2-, and 2-fold higher in Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice than wt mice. The dTTP and dCTP pools in Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− were approximately 2 times higher than in Dm-dNK+/− mice and the dGTP and dATP pools were approximately 1.5 times higher in Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− than Dm-dNK+/− mice. Mitochondrial dNTP pools were measured in liver of 4–18-month-old wt and Dm-dNK+/− mice (data not shown). No significant difference was observed in all 4 dNTP pools in wt and Dm-dNK+/− mice.

TABLE 4.

dNTP pools in skeletal muscle of 12-month-old mice

Data represent mean ± S.E. of respective dNTPs measurements in whole cell skeletal muscle extracts from three mice of each group.

| dNTPs | dNTP concentration |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Dm−dNK+/− | Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− | |

| pmol of dNTP/mg tissue | |||

| dTTP | 0.19 ± 0.07 | 18.7 ± 1.2 | 40.0 ± 4.5 |

| dCTP | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 0.50 ± 0.07 | 1.02 ± 0.23 |

| dGTP | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.45 ± 0.1 | 0.71 ± 0.09 |

| dATP | 0.18 ± 0.10 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.33 ± 0.07 |

DNA point mutations were determined in the coding region of the nuclear Hprt gene and in the mitochondrial mt-Cytb gene in skeletal muscle of 12-month-old wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice (Table 5). There was no difference in mutation frequencies in both the Hprt gene (1.7, 2.0 and 2.4 mutations/10 kb) and the mt-Cytb gene (2.2, 1.66, and 1.48 mutations/10 kb) (p > 0.05) in wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice, respectively.

TABLE 5.

Mutation analysis of nuclear and mitochondrial genes

Mutation analysis of coding region of the nuclear Hprt gene and mt-Cytb gene in skeletal muscle of 12-month-old mice.

| Mouse (genotype) | Number of mutations/base pairs sequenced |

Mutation frequency (per 10 kb) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hprt-coding region | mt-Cytb | Hprt-coding region | mt-Cytb | |

| wt-1 | 0/8514 | 1/8340 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| wt-2 | 0/9267 | 2/8132 | 0.0 | 2.5 |

| wt-3 | 2/8160 | 0/8340 | 2.5 | 0.0 |

| wt-4 | 0/6552 | 1/8340 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| wt-5 | 5/8998 | 5/8256 | 5.6 | 6.1 |

| Dm-dNK+/−-1 | 1/8215 | 1/7458 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Dm-dNK+/−-2 | 0/8134 | 0/7091 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Dm-dNK+/−-3 | 2/8679 | 3/5182 | 2.3 | 5.8 |

| Dm-dNK+/−-4 | 2/8275 | 0/8340 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| Dm-dNK+/−-5 | 3/7593 | 1/8340 | 4.0 | 1.2 |

| Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/−-1 | 1/6855 | 2/5896 | 1.5 | 3.4 |

| Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/−-2 | 2/8291 | 0/5789 | 2.3 | 0.0 |

| Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/−-3 | 0/7149 | 0/8340 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/−-4 | 2/7182 | 3/7507 | 2.8 | 4.0 |

| Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/−-5 | 4/8303 | 0/7506 | 4.8 | 0.0 |

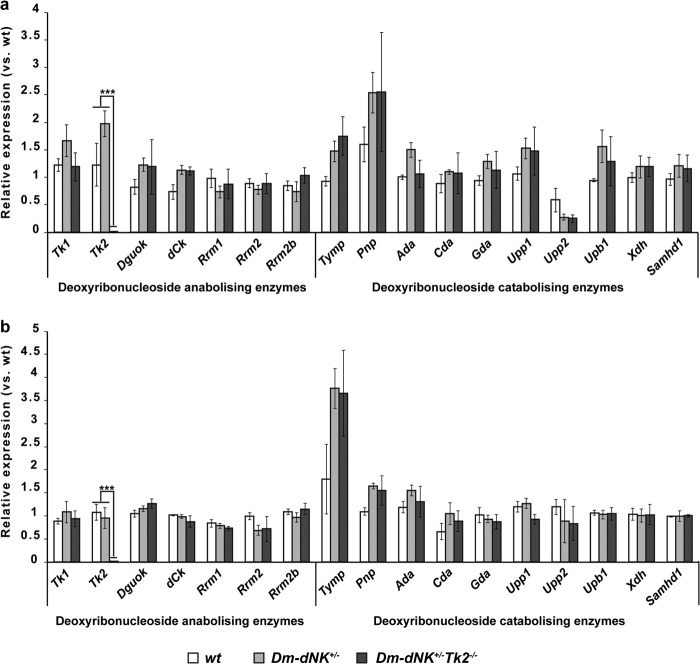

mRNA levels of several deoxyribonucleoside metabolizing enzymes were compared in skeletal muscle (Fig. 4a) and liver (Fig. 4b) of 12-month-old wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice. Tk2 was knocked down in Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice. The deoxyribonucleotide catabolizing enzymes Tymp, Pnp, and Ada were observed to be up-regulated in the Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice as compared with the wt mice. No significant difference was observed in expression levels of other deoxyribonucleotide metabolizing enzymes.

FIGURE 4.

Gene expression analysis of genes involved in deoxyribonucleotide metabolism (anabolism and catabolism) in skeletal muscle (a) and liver (b) of 12-month-old mice. Tk1, thymidine kinase 1; Tk2, thymidine kinase 2; Dguok, deoxyguanosine kinase; dCk, deoxycytidine kinase; Rrm1, ribonucleotide reductase M1; Rrm2, ribonucleotide reductase M2; Rrm2b, ribonucleotide reductase M2b (p53 inducible); Tymp, thymidine phosphorylase; Pnp, purine nucleoside phosphorylase; Ada, adenosine deaminase; Cda, cytidine deaminase; Gda, guanine deaminase; Upp, uridine phosphorylase (1 and 2); Upb1, β-ureidopropionase; Xdh, xanthine dehydrogenase; Samhd1, sterile α motif and HD-domain containing protein 1. All data are represented as mean ± S.E.; p < 0.005 (***).

Histopathology, Immunohistochemistry, and Electron Microscopy

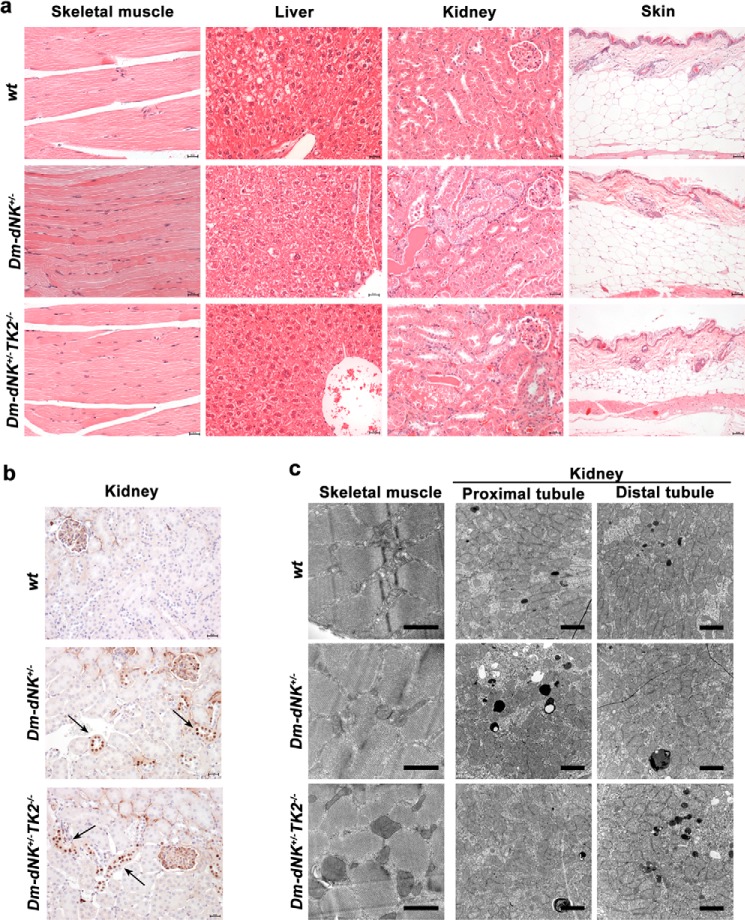

Histological analysis of tissues from 12- and 18–20-month-old wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice (three mice of each group) showed no major abnormalities in the Dm-dNK expressing mice as compared with wt mice in liver, heart, and spleen. Skeletal muscle showed an increased number of muscle cross-section and centralization of nuclei in the Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice, indicating thinner fibers and an attempt to regeneration. Kidneys showed thickening of the glomerular membranes and scattered tubular protein casts, as well as mild tubular degeneration in the Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice. Mild focal cortical mononuclear infiltration was also observed in all the mice. The 18–20-month-old mice were investigated for their subcutaneous fat content and showed substantial reduction compared with the wt and Dm-dNK+/− mice (Fig. 5a).

FIGURE 5.

Histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. a, histopathology of various tissues from wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice (18–20 months old). Each picture is representative of three independent mice of each group; skin histopathology sections are representative of two mice from each group (skeletal muscle, liver, and kidney, original magnification ×20 and scale bar, 25 μm; skin, original magnification ×10 and scale bar, 50 μm). b, immunohistochemistry on kidney sections of 12-month-old mice. Arrows indicate regions of histidine-tagged Dm-dNK expression (original magnification ×20 and scale bar, 25 μm). c, electron microscopy of skeletal muscle and kidney (proximal and distal tubules) mitochondria from 18–20-month-old mice. Each picture is a representative image from one of three independent mice in each group. Bars represent 1 μm (skeletal muscle) and 2 μm (kidney).

Immunohistochemistry staining was performed on kidney sections to determine localization of the His6-Dm-dNK protein using anti-histidine antibody and nuclear localization of the protein was observed in Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice. Dm-dNK was expressed in the some cells of the glomeruli and tubules, but not constitutively expressed at detectable levels in other cell types of the kidney (Fig. 5b).

Mitochondrial structure and density (number of mitochondria per cell cross-section) were examined in skeletal muscle and kidney (proximal and distal tubules). There was no significant difference in the relative mitochondrial volume (%) in kidney or skeletal muscle of 18–20-month-old wt, Dm-dNK+/−, and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice (Table 6). The mitochondria in the Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice were observed to be intact (Fig. 5c) unlike in Tk2−/− mice (3, 15).

TABLE 6.

Mitochondrial density in 18–20-month-old mice

Data represent mean ± S.E. of mitochondrial density from three mice of each group.

| Mouse (genotype) | Relative volume (%) Kidney |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal muscle | Proximal | Distal | |

| WT | 6.2 ± 1.0 | 48 ± 2 | 57 ± 3 |

| Dm-dNK+/− | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 48 ± 3 | 57 ± 2 |

| Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 46 ± 4 | 53 ± 3 |

DISCUSSION

In the present study we have investigated the long term effects of Dm-dNK expression in Tk2-deficient mice. Interestingly, the Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice survived equally long as wt and Dm-dNK+/− mice and showed no behavioral alterations. The only apparent gross difference observed in the Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice was a reduction of total body fat, illustrated by lack of fat tissue in the abdomen as well as decreased subcutaneous fat. The Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice were not observed to eat less, or have less access to food, as compared with the other mice. The absence of fat was similar to what was observed in the Tk2−/− mice and therefore we speculate that this was a result of insufficient mitochondrial function (3, 14). However, there was no clear mtDNA depletion detected in the tissues investigated although a slight decrease in liver mtDNA in 12-month-old mice could indicate that mtDNA synthesis is not fully compensated for by Dm-dNK expression in these mice. The observation that the Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice lived as long as the wt mice, with the only sign of possible dysfunctional mitochondria resulting in altered fat metabolism, suggests that Dm-dNK compensated mitochondria can support vital functions, if not completely reverting to a wt phenotype in certain tissues. An ordered decline in mitochondrial function with altered storage of fat as an early sign would be in agreement with the phenotype of a normal and healthy aging process in humans. Previous studies suggest a mechanistic relationship between the lack of fat tissue and deficient mitochondrial function that becomes severe when the mtDNA levels in the liver drop below a threshold and cause insufficient mitochondrial function in the liver (14). No significant difference in mtDNA copy number was observed in skeletal muscle of all ages, suggesting that the high Dm-dNK expression in skeletal muscle was able to compensate for mtDNA synthesis to a larger extent as compared with tissues with low Dm-dNK expression, such as liver and adipose tissues.

The activity of Dm-dNK enzyme was consistent at all time points investigated during the 20 months of study. The expression level differed between different tissues because of the CMV promoter (16), and although the Dm-dNK expression was higher in skeletal muscle and kidney as compared with brain and liver, these tissues developed normally due to the compensatory transgene. The dThd phosphorylating activity, mainly derived from Dm-dNK activity, in 12- and 18–20-month-old mice was similar to that observed in 1–6-month-old mice (>100-fold higher activity compared with wt) in support of a stable expression of Dm-dNK. Although the Dm-dNK activity in liver extracts of Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice was ∼25 times lower than in skeletal muscle or kidney, a direct comparison of enzyme activity between different tissues is difficult because the determinations were performed in crude tissue extracts, with a large mixture of other enzymes present in the assay.

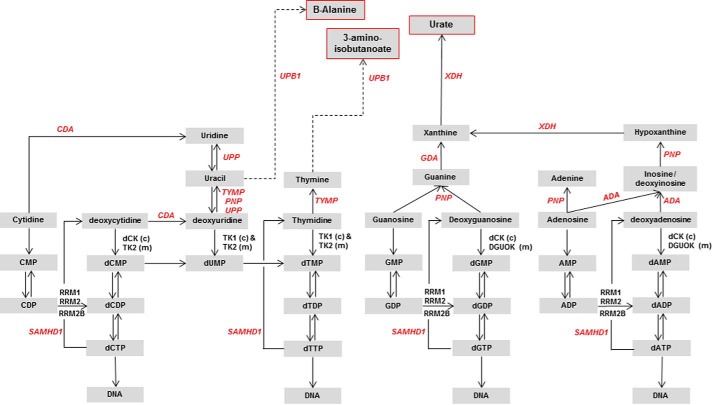

The high catalytic activity of Dm-dNK results in a very special intracellular composition of the dNTP pools. Normally the dNTP pool sizes are regulated by anabolic and catabolic pathways (Fig. 6). The 5′-nucleotidases (cytosolic and mitochondrial) are involved in dephosphorylation of deoxyribonucleoside monophosphates to deoxyribonucleosides that are further catabolized by specific phosphorylases and deaminases such as TYMP, uridine phosphorylase (UPP), PNP, and adenosine deaminase (ADA) to their respective bases (17–19). Recently, a triphosphohydrolase, sterile α motif HD-domain containing protein 1 (SAMHD1) has been shown to catabolize the dNTPs to their respective nucleosides (20, 21). Deficiencies of specific enzymes in these pathways lead to accumulation of toxic metabolites and cause severe diseases (22–25). In our mouse model the regulation of the dNTP pools was altered due to the expression of Dm-dNK, which resulted in a very large increase of the dTTP pool. However, liver mitochondrial dNTP pools remain unaltered in Dm-dNK+/− mice compared with wt mice, showing a strict regulation of dNTP pool balance in the mitochondria. To our knowledge the Dm-dNK mouse model is the first living model of a pronounced dNTP pool imbalance and therefore our observation that the mice are quite unaffected by the alteration throughout their life span, and also that DNA synthesis is without increased mutations in both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, is remarkable. Our findings are in agreement with previous studies demonstrating that a decrease, or absence, of any of the deoxyribonucleotides has adverse effects on the mtDNA levels and affect the fidelity of DNA synthesis (26–29), but do not have any lethal effects with increased dNTP pools. However, presently observed alterations in nucleotide catabolizing enzyme levels should be regarded as a tentative response to the high levels of dNTPs in the Dm-dNK expressing mice. The Tymp gene was up-regulated in the Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice in both skeletal muscle and liver, indicating increased catabolism of dThd to thymine. An increase in mRNA levels of some of the other catabolic enzymes such as Pnp and Ada (in both liver and skeletal muscle) in Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice as compared with wt mice could also be observed. This indicates a call for increased breakdown of purine and pyrimidine nucleosides, most likely due to increased dNTP pools. The histopathology of kidney samples revealed mild protein casts and glomerular membrane thickening in both Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice that may be caused by a response to break down products of excess purines and/or pyrimidines that are similar to purine and pyrimidine catabolism disorders (30). In addition, skeletal muscle showed increased degenerative/regenerative changes in the fibers with increased nuclei and reduction in thickness of fibers in Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice. We conclude that the alterations found in purine and pyrimidine metabolism were caused by the expression of Dm-dNK because it was observed in both Dm-dNK+/− and Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice, but not in wt mice. There were no changes in mitochondrial structure or density in kidney (proximal and distal tubules) or skeletal muscle.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic representation of purine and pyrimidine metabolism. The enzymes involved in nucleoside/deoxynucleosides anabolism and catabolism are in black and red italics, respectively. End products of purine and pyrimidine catabolism are marked with red boxes. Dotted arrows represent presence of intermediates catalyzed by other enzymes: CDA, cytidine deaminase; RRM1, ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase subunit M1; RRM2, ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase subunit M2; RRM2B, ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase subunit M2 (p53 inducible); SAMHD1, sterile α motif and HD-domain containing protein 1; TK, thymidine kinase (TK1 and TK2); TYMP, thymidine phosphorylase; UPB1, ureidopropionase β 1; UPP, uridine phosphorylase (UPP1 and UPP2); XDH, xanthine dehydrogenase; c, cytosolic; m, mitochondrial.

Based on our findings, we suggest Dm-dNK as a possible gene for substitution of TK2 deficiency. There are several remaining questions to address for a gene therapy approach such as the level of expression sufficient to compensate the dTTP production and if an intermittent local expression would be possible. In earlier gene therapy studies using herpes simplex virus type 1-thymidine kinase 1 (HSV-TK1), bystander effects were commonly reported (31). The bystander effect was believed to be caused by transport of the HSV-TK-phosphorylated compound to cells without HSV-TK expression. Recent studies have demonstrated adeno-associated virus vector-mediated gene therapy to treat MNGIE in murine models (32). An enzyme such as Dm-dNK that has high catalytic activity is hence a possible candidate for therapy because even a short term expression could increase the dTTP pools substantially to rescue the mtDNA depletion. If Dm-dNK expression in a single tissue can sustain mtDNA synthesis in other tissues will be addressed as a next step in our investigation.

The present study contributes to the understanding of how dNTP pool alterations affect living cells and organisms. It is well established by previous studies and clinical observations that a shortage of any dNTP is a severe condition and that a pronounced shortage of any dNTP may not be compatible with life (1, 3, 33–35). It is also well documented that deficiencies in catabolic pathways of nucleotides can cause severe conditions. Loss of function mutations in the TYMP gene are known to cause mitochondrial neuro-gastrointestinal encephalomyopathy (MNGIE) and dysfunction of this enzyme causes elevated dTTP pools (22, 36, 37). However, a decrease in dCTP pools by feedback regulation of TK2 catalyzed dCyt phosphorylation by dTTP is suggested to be the reason for mtDNA depletion in MNGIE (29). Mutations or deletions of PNP and ADA genes also cause severe conditions characterized by progressive and severe combined immunodeficiency affecting the development of T-cells, B-cells, and NK-cells (23).

Our mouse model demonstrates that, with all compensatory pathways functioning, the mice can handle increased dNTP pools and that over-compensating a dNTP deficiency is not a very severe condition. This is in great contrast to the severity of a shortage of substrate for mtDNA synthesis. Another interesting observation in our study is the possible early effects on fat metabolism of a decline in mitochondrial function, most probably in liver or fat tissue. The alteration in fat metabolism was a clear phenotypic difference of the Dm-dNK+/−Tk2−/− mice and therefore should be linked to the genetic deficiency of Tk2 that was only present in these mice. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the mechanisms of a decline of specific mitochondrial functions, whereas keeping other life sustaining mitochondrial functions, in the same organ. Our unique mouse model is well suitable for such future studies related to dNTP imbalance and particularly syndromes characterized or complicated by altered dNTP turnover.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Nicola Solaroli for kind advice with measurement of the dATP pools.

This work was supported by Swedish Cancer Society Grant CAN 2011/1277, Swedish Research Council Grant 2010-2828, and the Karolinska Institutet.

- mtDNA

- mitochondrial DNA

- DGUOK

- deoxyguanosine kinase

- Dm-dNK

- Drosophila melanogaster nucleoside kinase

- dNK

- deoxyribonucleoside kinase

- Hprt

- nuclear hypoxanthine-phosphoribosyl transferase

- HSV-TK

- herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase

- MNGIE

- mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy

- mt-Cytb

- mitochondrial cytochrome b

- PNP

- purine nucleoside phosphorylase

- TYMP

- thymidine phosphorylase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Saada A., Shaag A., Mandel H., Nevo Y., Eriksson S., Elpeleg O. (2001) Mutant mitochondrial thymidine kinase in mitochondrial DNA depletion myopathy. Nat. Genet. 29, 342–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang L., Saada A., Eriksson S. (2003) Kinetic properties of mutant human thymidine kinase 2 suggest a mechanism for mitochondrial DNA depletion myopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6963–6968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou X., Solaroli N., Bjerke M., Stewart J. B., Rozell B., Johansson M., Karlsson A. (2008) Progressive loss of mitochondrial DNA in thymidine kinase 2-deficient mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 2329–2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Munch-Petersen B., Piskur J., Sondergaard L. (1998) Four deoxynucleoside kinase activities from Drosophila melanogaster are contained within a single monomeric enzyme, a new multifunctional deoxynucleoside kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3926–3931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johansson M., van Rompay A. R., Degrève B., Balzarini J., Karlsson A. (1999) Cloning and characterization of the multisubstrate deoxyribonucleoside kinase of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 23814–23819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Solaroli N., Johansson M., Balzarini J., Karlsson A. (2007) Enhanced toxicity of purine nucleoside analogs in cells expressing Drosophila melanogaster nucleoside kinase mutants. Gene Ther. 14, 86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Solaroli N., Zheng X., Johansson M., Balzarini J., Karlsson A. (2007) Mitochondrial expression of the Drosophila melanogaster multisubstrate deoxyribonucleoside kinase. Mol. Pharmacol. 72, 1593–1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krishnan S., Zhou X., Paredes J. A., Kuiper R. V., Curbo S., Karlsson A. (2013) Transgene expression of Drosophila melanogaster nucleoside kinase reverses mitochondrial thymidine kinase 2 deficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 5072–5079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martí R., Dorado B., Hirano M. (2012) Measurement of mitochondrial dNTP pools. Methods Mol. Biol. 837, 135–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sherman P. A., Fyfe J. A. (1989) Enzymatic assay for deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates using synthetic oligonucleotides as template primers. Anal. Biochem. 180, 222–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferraro P., Franzolin E., Pontarin G., Reichard P., Bianchi V. (2010) Quantitation of cellular deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sheikhi M., Hultenby K., Niklasson B., Lundqvist M., Hovatta O. (2013) Preservation of human ovarian follicles within tissue frozen by vitrification in a xeno-free closed system using only ethylene glycol as a permeating cryoprotectant. Fertil. Steril. 100, 170–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park C. B., Asin-Cayuela J., Cámara Y., Shi Y., Pellegrini M., Gaspari M., Wibom R., Hultenby K., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Falkenberg M., Gustafsson C. M., Larsson N. G. (2007) MTERF3 is a negative regulator of mammalian mtDNA transcription. Cell 130, 273–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou X., Kannisto K., Curbo S., von Döbeln U., Hultenby K., Isetun S., Gåfvels M., Karlsson A. (2013) Thymidine kinase 2 deficiency-induced mtDNA depletion in mouse liver leads to defect β-oxidation. PLoS One 8, e58843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Paredes J. A., Zhou X., Höglund S., Karlsson A. (2013) Gene expression deregulation in postnatal skeletal muscle of TK2 deficient mice reveals a lower pool of proliferating myogenic progenitor cells. PLoS One 8, e53698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schmidt E. V., Christoph G., Zeller R., Leder P. (1990) The cytomegalovirus enhancer: a pan-active control element in transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 4406–4411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gazziola C., Ferraro P., Moras M., Reichard P., Bianchi V. (2001) Cytosolic high K-m 5′-nucleotidase and 5′(3′)-deoxyribonucleotidase in substrate cycles involved in nucleotide metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6185–6190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bianchi V., Spychala J. (2003) Mammalian 5′-nucleotidases. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46195–46198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rampazzo C., Fabris S., Franzolin E., Crovatto K., Frangini M., Bianchi V. (2007) Mitochondrial thymidine kinase and the enzymatic network regulating thymidine triphosphate pools in cultured human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34758–34769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lahouassa H., Daddacha W., Hofmann H., Ayinde D., Logue E. C., Dragin L., Bloch N., Maudet C., Bertrand M., Gramberg T., Pancino G., Priet S., Canard B., Laguette N., Benkirane M., Transy C., Landau N. R., Kim B., Margottin-Goguet F. (2012) SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat. Immunol. 13, 223–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goldstone D. C., Ennis-Adeniran V., Hedden J. J., Groom H. C., Rice G. I., Christodoulou E., Walker P. A., Kelly G., Haire L. F., Yap M. W., de Carvalho L. P., Stoye J. P., Crow Y. J., Taylor I. A., Webb M. (2011) HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature 480, 379–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nishino I., Spinazzola A., Hirano M. (1999) Thymidine phosphorylase gene mutations in MNGIE, a human mitochondrial disorder. Science 283, 689–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hirschhorn R. (1983) Genetic deficiencies of adenosine deaminase and purine nucleoside phosphorylase: overview, genetic heterogeneity and therapy. Birth Defects Orig. Artic. Ser. 19, 73–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haraguchi M., Tsujimoto H., Fukushima M., Higuchi I., Kuribayashi H., Utsumi H., Nakayama A., Hashizume Y., Hirato J., Yoshida H., Hara H., Hamano S., Kawaguchi H., Furukawa T., Miyazono K., Ishikawa F., Toyoshima H., Kaname T., Komatsu M., Chen Z. S., Gotanda T., Tachiwada T., Sumizawa T., Miyadera K., Osame M., Yoshida H., Noda T., Yamada Y., Akiyama S. (2002) Targeted deletion of both thymidine phosphorylase and uridine phosphorylase and consequent disorders in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5212–5221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Franzolin E., Pontarin G., Rampazzo C., Miazzi C., Ferraro P., Palumbo E., Reichard P., Bianchi V. (2013) The deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase SAMHD1 is a major regulator of DNA precursor pools in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 14272–14277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kumar D., Viberg J., Nilsson A. K., Chabes A. (2010) Highly mutagenic and severely imbalanced dNTP pools can escape detection by the S-phase checkpoint. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 3975–3983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Frangini M., Franzolin E., Chemello F., Laveder P., Romualdi C., Bianchi V., Rampazzo C. (2013) Synthesis of mitochondrial DNA precursors during myogenesis, an analysis in purified C2C12 myotubes. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 5624–5635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mathews C. K. (2006) DNA precursor metabolism and genomic stability. FASEB J. 20, 1300–1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. González-Vioque E., Torres-Torronteras J., Andreu A. L., Martí R. (2011) Limited dCTP availability accounts for mitochondrial DNA depletion in mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy (MNGIE). PLoS Genet. 7, e1002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martinon F. (2010) Update on biology: uric acid and the activation of immune and inflammatory cells. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 12, 135–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zheng X., Johansson M., Karlsson A. (2001) Bystander effects of cancer cell lines transduced with the multisubstrate deoxyribonucleoside kinase of Drosophila melanogaster and synergistic enhancement by hydroxyurea. Mol. Pharmacol. 60, 262–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Torres-Torronteras J., Viscomi C., Cabrera-Pérez R., Cámara Y., Di Meo I., Barquinero J., Auricchio A., Pizzorno G., Hirano M., Zeviani M., Martí R. (2014) Gene therapy using a liver-targeted AAV vector restores nucleoside and nucleotide homeostasis in a murine model of MNGIE. Mol. Ther. 22, 901–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Saada A. (2008) Mitochondrial deoxyribonucleotide pools in deoxyguanosine kinase deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 95, 169–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Copeland W. C. (2012) Defects in mitochondrial DNA replication and human disease. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 47, 64–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tyynismaa H., Suomalainen A. (2010) Mouse models of mtDNA replication diseases. Methods 51, 405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Valentino M. L., Martí R., Tadesse S., López L. C., Manes J. L., Lyzak J., Hahn A., Carelli V., Hirano M. (2007) Thymidine and deoxyuridine accumulate in tissues of patients with mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy (MNGIE). FEBS Lett. 581, 3410–3414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. López L. C., Akman H. O., García-Cazorla A., Dorado B., Martí R., Nishino I., Tadesse S., Pizzorno G., Shungu D., Bonilla E., Tanji K., Hirano M. (2009) Unbalanced deoxynucleotide pools cause mitochondrial DNA instability in thymidine phosphorylase-deficient mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 714–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]