Abstract

Introduction

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition introduced major changes in the staging of lung cancer, including Tumor (T), Node (N), Metastasis (M) (TNM) system and new stage/prognostic site-specific factors (SSFs), collected under the Collaborative Stage Version 2 (CSv2) Data Collection System. The intent was to improve the stage precision which could guide treatment options and ultimately lead to better survival. This report examines stage trends, the change in stage distributions from the AJCC 6th to the 7th edition, and findings of the prognostic SSFs for 2010 lung cancer cases.

Methods

Data were from the November 2012 submission of 18 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program population-based registries. A total of 344 797 cases of lung cancer, diagnosed in 2004–2010, were analyzed.

Results

The percentages of small tumors and early stage lung cancer cases increased from 2004 to 2010. The AJCC 7th edition, implemented for 2010 diagnosis year, subclassified tumor size and reclassified multiple tumor nodules, pleural effusions, and involvement of tumors in the contralateral lung, resulting in a slight decrease in stage IB and stage IIIB and a small increase in stage IIA and stage IV. Overall about 80% of cases remained the same stage group in AJCC 6th and 7th editions. About 21% of lung cancer patients had separate tumor nodules in the ipsilateral (same) lung, and 23% of the surgically resected patients had visceral pleural invasion, both adverse prognostic factors.

Conclusion

It is feasible for high quality population-based registries such as the SEER Program to collect more refined staging and prognostic SSFs that allows better categorization of lung cancer patients with different clinical outcomes and to assess their survival.

Keywords: Lung cancer, collaborative stage, AJCC, prognostic site-specific factors

INTRODUCTION

Lung and bronchus cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths and the second most common cancer among American men and women. It is estimated that there will be 224 210 new cases of lung and bronchus cancer diagnosed and 159 260 deaths from this malignancy in 2014.1 The 2006–2010 incidence rates from the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program’s18 geographic regions (SEER-18) were 74.3 per 100 000 among men and 51.9 per 100 000 among women. The corresponding death rates for lung cancer in the United States (US) were 63.5 for men and 39.2 for women. The higher rates among males were consistently observed for both incidence and mortality and in all racial and ethnic groups, including whites, blacks, Asians and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics.2

The SEER incidence trends showed a steady and significant decline in lung cancer among males since 1991 but only since 2007 among females, a lag of 16 years.2 Mortality showed similar trends, with decreasing US death rates observed in men beginning in 1995. The death rate among women did not start to trend downward until 2004, reflecting the gender-specific smoking patterns in the US population.3–5

Although the US has made great strides in primary prevention of lung cancer (reducing the smoking rate by preventing the initiation or cessation of smoking, as well as reducing exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and occupational carcinogens), progress in secondary and tertiary prevention has lagged behind. It was only after the reduced lung cancer mortality from the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) was established6 that the key professional organizations recommended annual screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) in “high risk” individuals.7–11 Only 15% of all lung cancer cases diagnosed in 2003–2009 in the SEER Program were localized disease, 22% were diagnosed with regional involvement, and 57% with distant metastases.2 Among patients with small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC, which accounted for 13.6% of all lung cancer cases), the statistics were even more dismal, with more than 90% of cases diagnosed in late stages (21% regional and 72% distant).2 The overall 5-year relative survival rate for lung cancer in the SEER-9 areas for 2003 to 2009 was 17.5%, with slightly better outcomes among females than males, whites than blacks, and non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) than SCLC; but all of these groups experienced 5-year relative survival rates of less than 20%.2 Furthermore, survival rates have improved only slightly from 12.2% in 1975–1977 to 17.5% in 2003–2009 in the SEER-9 areas (where long -term survival trends are available), in contrast to more substantial improvement in survival for breast and prostate cancers2.

Studies have shown, however, that lung cancer patients with operable tumors experienced more favorable outcomes; their 5-year survival rate ranged from 20%–70%, in contrast to the overall rate of 16%.12,13 Unfortunately, less than one-quarter of lung cancer patients received any surgical resection in 2010 (unpublished data from the SEER 2012 November data submission). Therefore, refined staging of tumors in lung cancer is critical for identifying patients suitable for surgery, especially for NSCLC patients, and for exploring treatment options and predicting prognosis.

Based on extensive analyses and evidence from a large international database (more than 100 000 lung cancer cases from more than 19 countries),14 the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) made recommendations for improved lung cancer staging.15–19 These recommendations were accepted by the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC, formerly named International Union Against Cancer) and became the primary source for the revisions of the lung cancer chapter in the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging Manual.20 The AJCC 7th edition also introduced new data variables that were intended to support more refined staging, allow for more accurate prediction of prognosis, and better guide lung cancer treatment options. Several cancer organizations, including the American College of Surgeons (ACoS), the NCI, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), adopted this new edition through updates to Collaborative Stage (CS) Data Collection System Version 2 (CSv2) and used them as guidelines for data collection in their respective cancer surveillance programs: the National Cancer Data Base, SEER, and the National Program of Cancer Registries. These additional data items for staging, prognosis, and clinical significance are referred to as site-specific factors (SSFs) in the CS Data Collection System.21

Objectives

The objectives of this chapter are to: (1) examine the trends in stage distribution for lung cancer based on data from 18 SEER Program registries from 2004 to 2010 by CS-derived AJCC 6th edition T (Tumor), N (Node), M (Metastasis) descriptors and stage, as well as derived SEER Summary Stage-2000, a staging system developed by the SEER Program which classifies the extent of disease into: in situ, localized, regional (with lymph node or extension or both) and distant metastasis22; (2) describe the differences in lung cancer staging between the AJCC 6th23 and 7th editions and examine how these changes impact stage distributions of the 2010 cases; and (3) assess the completeness and quality of lung cancer SSFs for 2010 cases, recorded according to the CSv2.

DATA DESCRIPTION

Schema of Lung Cancer and Exclusion Criteria

The data source corresponds to the November 2012 submission from 18 SEER registries. Case definition of lung cancer for the CSv2 schema is almost the same as the traditional SEER site recode, based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3).24 The ICD-O-3 topographies for lung are C34.0–C34.3, C34.8–C34.9, excluding lymphomas.

Because this analysis included a comparison of AJCC stage between the 6th and 7th editions, cases of histology groupings that are not staged in either of these editions were excluded. For example, carcinoids, staged under the AJCC 7th edition but not in the AJCC 6th edition, were ineligible. Lymphomas, sarcomas, and other rare tumors such as mesothelioma and pulmonary blastoma occurring in the lung also were excluded. In addition, cases diagnosed at autopsy or death certificate only (DCO) were excluded, as these cases often contain little information (Table 1). In 2004–2010, lung cancer cases identified by DCO or at autopsy represented only 2% of total lung cancer cases.

TABLE 1.

Lung Cancer: Exclusion Criteria, Years of Diagnosis, and Number of Cases for Analysis Cohorts, SEER-18

| Stage Trends | AJCC 6th & 7th Comparison | SSFs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective 1 | Objective 2 | Objective 3 | |

| Exclusion Criteria: | |||

| In situ cases | no | no | yes |

| Autopsy or death certificate only cases | yes | yes | yes |

| Histologies for which AJCC 6th or 7th edition stages are not defineda | yes | yes | yes |

| Code 988, blank for each SSF | no | no | yes |

| Year of Diagnosis | 2004–2010 | 2010 | 2010 |

| Final Sample Size | 344797 | 48315 | 48263 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; SSF, site-specific factor.

AJCC 6th or 7th editions derived stage = Not applicable (NA) for undefined histologies

Source: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington.

Analysis Cohorts

To examine the trends of CS-derived AJCC 6th edition stage, including TNM and SEER Summary Stage-2000 (objective #1), all lung cancer cases—including both in situ and invasive—diagnosed between 2004 and 2010 were selected (N = 344 797). For objective #2, our analysis was limited to lung cancer cases diagnosed in 2010 (N = 48 315). When assessing the SSFs for quality and completeness in objective #3, we used only invasive cases (N = 48 263) diagnosed in 2010, when the SSFs for lung cancer were collected for the first time. Only 52 lung cancer cases (0.12%) were diagnosed with in situ disease in 2010 (Table 1).

Key Changes in AJCC Staging in the 7th Edition

Several major changes occurred between the AJCC 6th and 7th editions, as summarized below:

-

Tumor (T) classification is divided into more refined subgroups:

T1 (≤3 cm) is subdivided into T1a (≤2 cm) and T1b (>2 cm to ≤ 3 cm).

T2 (>3 to 7 cm) is subdivided into T2a (>3 cm to ≤5 cm) and T2b (>5 cm to ≤7 cm).

T2 (>7 cm) is reclassified into T3.

The subdivision of the T1 tumor size into T1a and T1b does not affect stage. However, cases with tumor size greater than 3 cm and no lymph node involvement or distant metastases that were classified as stage IB in the AJCC 6th edition were reclassified as stages IB, IIA, and IIB in the AJCC 7th edition, corresponding to T2a, T2b, and T3. When tumor size is greater than 3 cm with lymph node involvement but no distant metastases, AJCC 7th edition stage varies compared to the AJCC 6th edition based on tumor size (T2a, T2b, or T3) and nodal status (N1, N2, or N3).

-

Multiple tumor nodules

Separate tumor nodules in the same lobe were reclassified (downstaged) from T4 to T3.

Separate tumor nodules in a different lobe of the ipsilateral (same) lung were reclassified (downstaged) from M1 to T4/M0.

T4 with or without nodal involvement and no distant metastasis (M0) was classified in the AJCC 6th edition as stage IIIB; in the AJCC 7th edition, it is subdivided into stage IIIA with N0 or N1 and remains stage IIIB with N2 or N3.

-

Distant metastasis (M) is redefined in the AJCC 7th edition:

M1 is subdivided into M1a and M1b.

Malignant pleural and pericardial effusions are reclassified (upstaged) from T4/M0 in the AJCC 6th edition to M1a in the 7th edition.

Separate tumor nodules in a contralateral lung are considered M1a, and distant metastases in extra-thoracic organs are classified as M1b. Both M1a and M1b are considered stage IV.

In the AJCC 6th edition, the MX category and its cases were staged as “unknown”; in the 7th edition, however, MX is treated as M0, and other staging information can be used to stage these cases.

SSFs

NCI’s SEER Program and hospitals with the ACoS Commission on Cancer-approved cancer program are required to collect SSFs using the CS Data Collection System. In 2004 when CS Version 1 (CSv1) was first implemented, no SSFs were defined for lung cancer. Two SSFs that relate to stage and prognosis, however, have been collected for lung cancer cases diagnosed in 2010 and after.

Table 2 shows the two SSFs for lung cancer that SEER registries have been collecting since 2010 under the CSv2 schema. A more detailed description of these SSFs is presented below.

TABLE 2.

Lung Cancer: SSFs and Their Description, Codes, and Applicability, SEER-18, 2010

| SSF | Not Applicable | Among Applicable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Known | Unknown | Total | ||||||||

| Codes | N | % | Codes | N | % | Codes | N | % | N | |

| 1. Separate Tumor Nodules - Ipsilateral Lung | 988, blanks | 0 | 0.0 | 000, 010, 020, 030, 040 | 42491 | 88.0 | 999 | 5772 | 12.0 | 48263 |

| 2. PL by H&E or Elastic Stains | 988, blanks | 0 | 0.0 | 000, 010, 020, 030, 040 | 15230 | 31.6 | 998, 999 | 33033 | 68.4 | 48263 |

| 2a. Surgical resection only (Surgical codes 20–24, 30–80) | 988, blanks | 0 | 0.0 | 000, 010, 020, 030, 040 | 8799 | 88.9 | 998, 999 | 1097 | 11.1 | 9896 |

Abbreviations: PL, Pleural/Elastic Layer Invasion; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results; SSF, site-specific factor; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin

Source: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington

Separate Tumor Nodules in the Ipsilateral Lung (SSF1)

The presence of separate tumor nodules (same lobe, different lobe, or both) in the ipsilateral lung is collected in SSF1 for CSv2. For cases coded prior to CSv2, information on separate tumor nodules is in the CS Extension and CS Mets fields. This SSF is used together with Tumor Size, Extension, and Metastasis at diagnosis to determine T and M in the AJCC 6th and 7th editions and SEER Summary Stage-2000. Information on separate tumor nodules in the ipsilateral lung can be obtained from imaging (clinical) or pathology reports. According to the coding instructions in the CS manual, if no separate tumor nodules are noted or mentioned in the imaging or pathology report, it is assumed that they are absent.21

Visceral Pleural Invasion/Elastic Layer (SSF2)

Visceral pleural invasion (VPI) is the invasion by tumor of one or more layers of the pleura covering the lung. Recognizing the importance of precise staging in identifying treatment options and predicting outcomes, the AJCC included a newly standardized definition of VPI for lung cancer in its 7th edition.

According to the CS Manual, “VPI is relevant for peripheral lung tumors. The presence of visceral pleural invasion by tumors smaller than 3 cm changes the T category from pT1 to pT2 and increases the stage from IA to IB in patients with no nodal disease and from stage IIA to IIB in patients with peribronchial or hilar nodes.”21 Studies have shown that tumors smaller than 3 cm that penetrate beyond the elastic layer of the visceral pleura behave similarly to similar-size tumors that extend to the visceral pleural surface.25 Therefore, in assessing VPI, pathologists should consider not only tumors that extend to the visceral pleural surface, but also tumors that penetrate beyond the elastic layer of the visceral pleura.

Four categories define VPI in the CSv2 system.21

PL0–The tumor is surrounded by lung parenchyma or invades superficially into the pleural connective tissue beneath the elastic layer but does not completely traverse the elastic layer of the pleura (not classified as pleural invasion for staging).

PL1–The tumor invades beyond the elastic layer (classified as T2 if the tumor size is <7cm).

PL2–The tumor extends to the surface of the visceral pleura (classified as T2 if the tumor size is <7cm).

PL3–The tumor invades the parietal pleura (classified as T3).

Information on VPI can be obtained only from pathology reports and thus applies only to lung cancer cases that have been surgically resected (surgery codes = 20–24, 30–80).26 Limited information on VPI also is collected in the CS Extension (for those cases that have no further extension); it is the information from the CS Extension that is used in the algorithm to derive the AJCC 6th and 7th edition T codes.

RESULTS

Trends in Stage Distributions for Lung Cancers, 2004–2010

A total of 344 797 lung cancer cases were diagnosed during 2004–2010. These cases were included in evaluating stage distribution trends using CS-derived AJCC 6th edition TNM and stage as well as CS-derived SEER Summary Stage-2000.

Trends in CS-Derived AJCC 6th Edition TNM Descriptors

Between 2004 and 2010, the percentages of CS-derived AJCC 6th edition T1 and T2 cases increased (with T1 showing the largest increase of 22%), whereas T3 cases declined slightly (Figure 1a). The percentages of T0, Tis, and T4 cases remained relatively stable during the 7-year period, and the “unknown” category decreased over time. When unknown T cases were excluded, the trend patterns remained similar, with the exception of T2 and T4 (Figure 1b). The increasing trend for T2 cases was no longer observed, and there was a slight decrease in the percentage of T4 cases, from 44% to 41%.

Figure 1.

Lung Cancer: Trends of Derived AJCC 6th Tumor (T), SEER-18 registries, 2004–2010 Data source: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington.

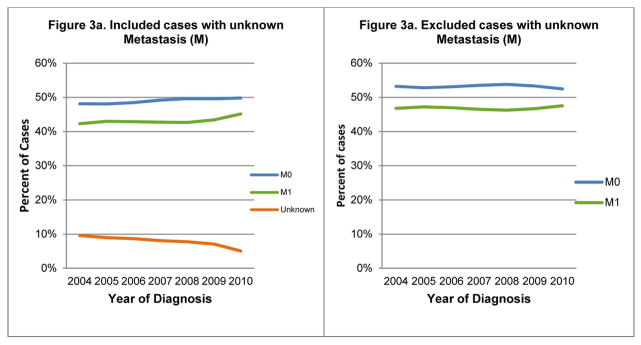

Although the percentages of N0 and N3 cases increased steadily and NX cases decreased overtime, N1 and N2 percentages remained level (Figure 2a). The trends remained similar after excluding the unknown N cases (Figure 2b). Figure 3a shows a slight increase in the percentages of M0 and M1 cases over time; MX (unknown distant metastasis status) decreased. The increasing trends for the M0 and M1 cases, however, were no longer observed after excluding unknown M cases (Figure 3b).

Figure 2.

Lung Cancer: Trends of derived AJCC 6th Node (N), SEER 18-registries, 2004–2010 Data source: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington.

Figure 3.

Lung Cancer: Trends of derived AJCC 6th Metastasis (M), SEER 18-registries, 2004–2010

Data source: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington.

Trends in AJCC 6th Edition Stage

Overall, changes in AJCC 6th edition stage distributions from 2004 to 2010 were not substantial. Percentages remained similar for the majority of stage groups except stages IA, IV, and unknown. The percentage increased from 9.0% to 11.7% for stage IA and from 42.3% to 45.1% for stage IV. In contrast, the percentage of cases classified as unknown decreased steadily, from 10.9% to 6.0% (Table 3; Figure 4a). When excluding unknown-stage cases, the trend remained similar for stage IA, but the increasing trend for stage IV was less obvious (Figure 4b).

TABLE 3.

Lung Cancer: Distribution of AJCC 6thEdition Stage by Year (2004–2010) and Comparison with AJCC 7th (2010 only), SEER-18

| Case Counts | AJCC 6th | AJCC 7th | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2010 |

| 0 | 27 | 33 | 35 | 31 | 36 | 33 | 52 | 52 |

| IA | 4316 | 4558 | 4847 | 5153 | 5379 | 5782 | 5643 | 5669 |

| IB | 3858 | 4059 | 4026 | 4275 | 4326 | 4426 | 4100 | 2957 |

| II NOSa | 38 | |||||||

| IIA | 492 | 477 | 533 | 494 | 526 | 472 | 461 | 1761 |

| IIB | 1597 | 1624 | 1571 | 1571 | 1659 | 1477 | 1508 | 1791 |

| III NOS | 691 | |||||||

| IIIA | 4275 | 4224 | 4281 | 4322 | 4241 | 4342 | 4083 | 5655 |

| IIIB | 7242 | 7270 | 7455 | 7347 | 7509 | 7353 | 7130 | 2699 |

| IV | 20368 | 21010 | 21207 | 21214 | 21294 | 21854 | 21806 | 23831 |

| Occult | 741 | 721 | 698 | 767 | 696 | 682 | 642 | 702 |

| Unknown | 5255 | 4910 | 4807 | 4472 | 4274 | 3958 | 2890 | 2469 |

| Total | 48171 | 48886 | 49460 | 49646 | 49940 | 50379 | 48315 | 48315 |

| Percent Distribution | AJCC 6th | AJCC 7th | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2010 |

| 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| IA | 9.0 | 9.3 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 10.8 | 11.5 | 11.7 | 11.7 |

| IB | 8.0 | 8.3 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 8.7 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 6.1 |

| II NOS | 0.1 | |||||||

| IIA | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 3.6 |

| IIB | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.7 |

| III NOS | 1.4 | |||||||

| IIIA | 8.9 | 8.6 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 11.7 |

| IIIB | 15.0 | 14.9 | 15.1 | 14.8 | 15.0 | 14.6 | 14.8 | 5.6 |

| IV | 42.3 | 43.0 | 42.9 | 42.7 | 42.6 | 43.4 | 45.1 | 49.3 |

| Occult | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| Unknown | 10.9 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.0 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 6.0 | 5.1 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; NOS = not otherwise specified; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Blank denotes 0 counts or percentages.

Source: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington.

Figure 4.

Lung Cancer: Trends of CS-derived AJCC stage 6th edition, SEER 18 registries, 2004–2010

Data source for all figures: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington.

Trends for CS-Derived SEER Summary Stage-2000

The percentages of in situ disease and distant stage were level over time (Figure 5a). About 55% of lung cancer cases had distant metastasis at diagnosis. The trends for localized disease and regional disease mirrored each other at about 20%, suggesting a shift from regional to localized stage. After excluding cases of unknown stage, the trends for SEER Summary Stage-2000 distributions remained similar (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Lung Cancer: Trends of CS derived SEER Summary Stage 2000, SEER 18 registries, 2004–2010

Abbreviation: SS2000= Summary Stage 2000

Data source: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington.

Comparison of AJCC Stage Distributions in the 6th and 7th Editions

A comparison of staging according to the AJCC 6th versus 7th editions for 48 315 lung cancer cases diagnosed in 2010 is presented in Table 3 (last 2 columns). Briefly, no differences were noted between the two classification schemes for stage 0. There was a slight decrease in stage I (20.2% vs. 17.8%) and stage III (23.3% vs. 18.7%) cases because substantially fewer cases were classified as stage IB and IIIB, respectively, by the 7th edition compared to the 6th edition. In contrast, there were increases in stage IIA (1.0% to 3.6%) and stage IV (45.1% to 49.3%) cases using the 7th edition guidelines compared with stage distribution under the AJCC 6th edition.

A more detailed illustration of stage changes between the two AJCC editions is presented in Table 4, which shows both upstage and downstage migration within and between stage groups. Overall, the application of the AJCC 6th and 7th editions resulted in the same stage for 81% of the cases. All cases staged as 0, IA, and Occult according to the 6th edition remained in the same stage under the 7th edition.

TABLE 4.

Lung Cancer: Summarized Comparison of AJCC 6th and 7th Edition Case Counts by Stage Groups and Subgroups, SEER-18, 2010

| Case Counts | AJCC 7th-2010 Cases | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AJCC 6th-2010 Cases | 0 | IA | IB | II NOS | IIA | IIB | III NOS | IIIA | IIIB | IV | Occult | Unknown | Total |

| 0 | 52 | 52 | |||||||||||

| IA | 5,643 | 5643 | |||||||||||

| IB | 2920 | 702 | 311 | 167 | 4100 | ||||||||

| IIA | 458 | 3 | 461 | ||||||||||

| IIB | 36 | 587 | 792 | 93 | 1508 | ||||||||

| IIIA | 454 | 3629 | 4083 | ||||||||||

| IIIB | 665 | 37 | 1267 | 2108 | 3043 | 10 | 7130 | ||||||

| IV | 43 | 511 | 464 | 20788 | 21,806 | ||||||||

| Occult | 642 | 642 | |||||||||||

| Unknown | 26 | 37 | 2 | 14 | 23 | 157 | 155 | 127 | 60 | 2289 | 2890 | ||

| Total | 52 | 5669 | 2957 | 38 | 1761 | 1791 | 691 | 5655 | 2699 | 23831 | 702 | 2469 | 48315 |

| Percent Distribution | AJCC 7th-2010 Cases | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AJCC 6th-2010 Cases | 0 | IA | IB | II NOS | IIA | IIB | III NOS | IIIA | IIIB | IV | Occult | Unknown | Total |

| 0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||||||||

| IA | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||||||||

| IB | 71.2 | 17.1 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 100.0 | ||||||||

| IIA | 99.3 | 0.7 | 100.0 | ||||||||||

| IIB | 2.4 | 38.9 | 52.5 | 6.2 | 100.0 | ||||||||

| IIIA | 11.1 | 88.9 | 100.0 | ||||||||||

| IIIB | 9.3 | 0.5 | 17.8 | 29.6 | 42.7 | 0.1 | 100.0 | ||||||

| IV | 0.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 95.3 | 100.0 | ||||||||

| Occult | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||||||||

| Unknown | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 4.4 | 2.1 | 79.2 | 100.0 | ||

| Total | 0.1 | 11.7 | 6.1 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 1.4 | 11.7 | 5.6 | 49.3 | 1.5 | 5.1 | 100.0 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; NOS, not otherwise specified; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Blank denotes 0 counts or percentages. Bold indicates agreement between the AJCC 6th and 7th editions. Underlined italics indicates migration between stage groups.

Source: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington.

There was a shift from the “unknown” stage in the AJCC 6th edition to specific stages in the 7th edition, primarily due to MX having been changed to M0; about 21% (N = 601) of the “unknown” stage cases were reassigned into a specific stage under the 7th edition guidelines. Conversely, fewer cases (N = 180) that were classified as a specific stage according to the 6th edition became unstaged according to 7th edition. Upstage migration (between stage groups) was observed among patients with stages IB and IIB tumors according to the 6th edition. The subdivision of T2 tumors into T2a and T2b, and the creation of T3 for tumors greater than 7 cm, resulted in about one-quarter of the cases that would have been staged as IB under the 6th edition moving to IIA (17.1%) and IIB (7.6%) under the 7th edition. In addition, about 6% of the cases staged as IIB according to the 6th edition became stage IIIA under the 7th edition, depending on regional lymph node status. In addition, the reclassification of malignant pleural and pericardial effusions and separate tumor nodules in contralateral lungs as M1a caused a substantial shift (42.7%) in tumors classified as stage IIIB under the 6th edition to stage IV under the 7th edition.

The revision of staging guidelines in the AJCC 7th edition also caused some downstaging. The reclassification of multiple tumor nodules in the same lobe from T4 to T3 resulted in about 9% of cases that would have been staged as IIIB according to the 6th edition being reclassified as stage IIB under the 7th edition. Similarly, the reclassification of multiple tumor nodules in the same lung but different lobes from M1 to T4 caused about a 5% shift from stage IV to stage III.

In addition to changes between AJCC stage groups, we also observed within-stage group migration (see Table 4) resulting from the staging revisions in the AJCC 7th edition.

SSFs

Separate Tumor Nodules in the Ipsilateral Lung (SSF1)

A total of 48 263 cases of invasive lung cancer diagnosed in 2010 were eligible for use in evaluating this SSF. Only 12% of the cases were coded as “unknown” for assessing separate tumor nodules in the same lung (see Table 5). About one-fifth (20.9%) of cases had separate tumor nodules present in the same lung at the time of diagnosis: 7.0% in the same lobe, 5.6% in a different lobe, 4.3% in both the same and a different lobe, and 4.0% had multiple nodules in the same lung but it was unknown whether they were in the same or a different lobe. The remaining 67.2% of cases had either no separate nodules or there was no mention of such involvement in either imaging or pathology reports.

TABLE 5.

Lung Cancer: SSF1—Separate Tumor Nodules in the Ipsilateral Lung, SEER-18, 2010

| Code | Description | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 48263 | 100.0 | |

| 000 | No separate nodules noted | 32454 | 67.2 |

| 010 | Separate tumor nodules in ipsilateral lung, same lobe | 3355 | 7.0 |

| 020 | Separate tumor nodules in ipsilateral lung, different lobe | 2706 | 5.6 |

| 030 | 020+010 Separate tumor nodules, ipsilateral lung, same and different lobe |

2068 | 4.3 |

| 040 | Separate tumor nodules, ipsilateral lung, unknown if same or different lobe | 1908 | 4.0 |

| 999 | Unknown if separate tumor nodules Separate tumor nodules cannot be assessed Not documented in patient record |

5772 | 12.0 |

Abbreviations: SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; SSF, site-specific factor.

Source: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington.

VPI/Elastic Layer (SSF2)

Surgical resection was performed in less than 3% (N = 171) of the 6131 SCLC cases and in 23.3% (N = 9725) of the 42 132 patients with NSCLC diagnosed in 2010 (Table 6). Among the resected SCLC patients (surgical codes = 20–24, 30–80), 20.5% had no or unknown assessment of VPI. More than half (56.1%) of cases showed no evidence of pleural invasion (PL0), 3.5% had tumors that invaded beyond the elastic layer but did not involve the surface of the pleura (PL1), 7.6% had tumors that extended to the surface of the visceral pleura (PL2), and 1.8% had tumors that extended to the parietal pleura (PL3). Approximately one-tenth of the cases had pleural invasion, not otherwise specified. Of the one-quarter of NSCLC patients who underwent surgical resection, only 10.9% did not have a recorded assessment of VPI. About 66% of cases had no evidence of invasion (PL0), 14% had invasion from PL1 to PL3, and 9.3% had pleural/visceral invasion noted with layer of invasion unknown.

TABLE 6.

Lung Cancer: SSF2—PL by Histologic Cell Type, SEER-18, 2010

| Code | Description | Small cell carcinoma | Non-small cell carcinoma | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical resectiona | No/Unknown surgical resectionb | Surgical resectiona | No/Unknown surgical resectionb | ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Total | 171 | 100.0 | 5960 | 100.0 | 9725 | 100.0 | 32407 | 100.0 | 48263 | 100.0 | |

| 000 | PL0: No evidence of visceral pleural invasion; Tumor does not completely traverse the elastic layer | 96 | 56.1 | 770 | 12.9 | 6406 | 65.9 | 4295 | 13.3 | 11567 | 24.0 |

| 010 | PL1: Invasion beyond the visceral elastic pleura, but limited to the pulmonary pleura; Tumor extends through the elastic layer | 6 | 3.5 | 8 | 0.1 | 638 | 6.6 | 74 | 0.2 | 726 | 1.5 |

| 020 | PL2: Invasion to the surface of the pulmonary pleura; Tumor extends to the surface of the visceral pleura | 13 | 7.6 | 11 | 0.2 | 478 | 4.9 | 76 | 0.2 | 578 | 1.2 |

| 030 | PL3: Tumor extends to the parietal pleura | 3 | 1.8 | 19 | 0.3 | 242 | 2.5 | 134 | 0.4 | 398 | 0.8 |

| 040 | Invasion of pleura, NOS | 18 | 10.5 | 139 | 2.3 | 899 | 9.2 | 905 | 2.8 | 1961 | 4.1 |

| 998 999 |

No histologic examination of pleura/Unknown if PL present | 35 | 20.5 | 5013 | 84.1 | 1062 | 10.9 | 26923 | 83.1 | 33033 | 55.2 |

Abbreviations: NOS, not otherwise specified; PL, visceral pleural/elastic layer invasion; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; SSF, site-specific factor.

Surgical resection included surgical codes 20–24, 30–80.

No or unknown surgical resection.

Source: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program: SEER 18 geographic areas: States of Connecticut, New Mexico, Utah, California (4 areas: San-Francisco, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Greater California), Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Georgia (3 areas: Atlanta, Rural Georgia, and remainder of the state), Alaska Native Registry, and metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle (Western Washington), Washington.

DISCUSSION

Despite lung cancer having been the leading cause of cancer death for decades in the US, survival rates have remained dismal and have shown little improvement.2 The major revision of staging in the AJCC 7th edition and the additional SSFs collected under the CSv2 system are intended to improve the precision of staging for lung cancer patients, which could better guide treatment options and ultimately lead to improved survival. In addition, the AJCC revisions arose partly because of differences in the nomenclature for the anatomical locations of lymph nodes between the lymph node maps used in Japan27 and in North America and Europe28 to describe nodal involvement. Adopting the proposed IASLC lymph node map resolved these discrepancies.16 This report is the initial examination of the use of SEER data to assess the impact of major revisions between the AJCC 6th and 7th editions on trends in stage and AJCC stage distributions for lung cancer. The findings will provide guidance to data users and suggest precautions in data interpretation.

All three CS-derived staging systems (TNM, AJCC 6th edition, and SEER Summary Stage-2000) show similar trends and patterns in stage distributions from 2004 to 2010. First, the percentage of cases in the “unknown” category steadily declined. Second, there has been an increase in small tumors at diagnosis, staged as T1 tumors (≤2 cm), AJCC stage IA tumors, and localized disease. Unfortunately, the increase in early stage lung cancer has not been offset by a reduction in stage IV tumors or lung cancer with distant metastases. A contributing factor to this observation could be the increase in the incidental finding of lung cancer by improved medical technology29 but not from the screening for lung cancer with LDCT among high-risk groups which was recommended by key professional organizations after the NLST findings were released in 2011.7–11 The small increase in stage IV lung cancer probably is due to the decrease in percentage of unknown stage cases; once those cases were excluded, the trend became less obvious.

When the 6th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual was introduced in 2002, no changes were made from the previous edition with regard to lung cancer. As a result, the staging of lung cancer cases through the 2000s was based on the AJCC 5th edition30 which was published in 1997 and based on evidence from one single institution with a relatively small database of NSCLC patients who primarily had been treated surgically.31 This staging system subsequently was challenged when better techniques such as CT and positron emission tomography (PET) scans became available for clinical staging. During development of the 7th edition of the AJCC TNM, the necessity of a major revision for lung cancer of both the descriptor (TNM) and stage groupings became evident. The IASLC established a Lung Cancer Staging Project that utilized large databases worldwide to revise both the descriptors and stage groupings, which subsequently were validated.14–19

The AJCC 7th edition reclassifies tumor size into the more refined T subgroups of T1a, T1b, T2a, and T2b and assigns T3 for tumors greater than 7 cm in size, allowing clinicians to select treatment options based on a patient’s tumor size and evaluate their clinical outcomes. The presence of multiple tumor nodules, a negative prognostic factor, has been downstaged from T4 to T3 (if in the same lobe) and from M1 to T4 (if in different lobes of the same lung). In addition, the presence of malignant pleural and pericardial effusion, another adverse prognostic factor, has been upgraded from T4 to M1a. As the SEER Program follows these patients, the appropriateness of the revised staging could be validated by their survival. Because of the major revisions in lung cancer staging in the AJCC 7th edition, researchers and data users must use caution when interpreting the data.

An analysis of multiple tumor nodules showed that about two-thirds of invasive lung cancer cases diagnosed in 2010 did not have separate tumor nodules noted in the same lung. Although the CS Manual instructs that when there is no mention of separate nodules in either imaging or pathology reports it could be interpreted as separate tumor nodules being absent, this assumption may not be true in all cases. Procedures followed in writing reports vary among pathologists, and overestimation of the percentage of lung cancer cases that lack separate tumor nodules is possible. Our analysis of SEER data showed that only 3% of the SCLC patients were treated surgically (the majority of SCLC cases were metastatic at diagnosis), whereas 23% of NSCLC patients underwent various types of surgical resection. The presence and the extent of VPI was recorded in 70–80% of the surgically treated patients, reflecting good adoption of the AJCC 7th edition’s newly standardized definition of VPI by pathologists and the recognition of the importance of precise staging.

In recent years, numerous molecular markers have been explored, and some were found to have prognostic value for lung cancer. For example, EGFR and bcl-2 are favorable prognostic factors; HER2, p53, KRAS, and Ki67, however, are associated with adverse outcomes.32 Although these molecular markers are being used to identify subsets of patients for treatment, none has been given the status of an SSF for inclusion in the population-based surveillance programs.

This report has multiple strengths. First, the data source is a high-quality cancer surveillance program that covers about 26% of the US population. Second, the data suggest the feasibility of collecting more refined staging data that allow better categorization of subgroups of patients with different clinical outcomes, such as patients with various tumor sizes or multiple tumor nodules. Third, the data collected on the two SSFs for lung cancer are quite complete and of good quality, especially when the source of the information is pathology reports.

This study also has limitations. The 2010 data are from the first year that CSv2 was introduced and collected by SEER registries, and extensive editing and quality control have not been implemented. In addition, the stage migrations that resulted from revisions in the AJCC 7th edition require backward comparability to interpret trends and survival. Comparison of stage distributions between the AJCC 6th and 7th editions showed good agreement for most stage groups. This, however, should not be used to rationalize combining AJCC 6th and 7th edition stage over time. CS should continue to be mapped to both the AJCC 6th (backward compatibility) and 7th editions so that researchers can use the AJCC 6th edition in evaluating long-term trends. Another limitation is that the primary data source for cancer registries is hospital medical records; therefore, any test results that are available only in physicians’ offices may not be recorded in the SEER database. In addition, although the SEER Program covers about one-quarter of the US population, its patient population may not be representative of those nationwide.

In summary, the initial examination of SEER data for stage distribution trends in lung cancer suggests an increase in small tumors and stage IA lesions. This finding may reflect the increasing use of CT scans, resulting in incidental findings of lung lesions. AJCC 7th edition stage revisions resulted in substantial stage shifts, both within and between stage groups, as well as upstage and downstage migration. Although these changes were intended to produce a more precise analysis of clinical outcome, caution is needed in interpreting the findings. Finally, analysis of the SSFs shows that separate tumor nodules in the ipsilateral lung were present in 21% of cases, and about 23% of the surgically resected lung cancer patients had VPI. As the population-based SEER registries follow these cohorts over the next few years, we hope to determine the impact of these clinically significant factors on relative survival. The collection of these SSFs, however, should take into consideration the current registries’ workload, cost, and resources.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part under NIH/NCI contract number HHSN261201000030C with Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (VWC, BAR, MCH, XCW); NIH/NCI contract number HHSN261201200422P with RiesSearch, LLC (LAR).

The authors are grateful for the review of the manuscript by J. Milburn, Jessup, MD.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: Findings and conclusions are the authors’ and do not necessarily represent the official positions of their affiliations, or those of the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

No financial disclosures for DL.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: Apr, 2013. [Accessed May 27, 2014]. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:175–201. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldron I. Patterns and causes of gender differences in smoking. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:989–1005. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connett JE, Murray RP, Buist AS, et al. Changes in smoking status affect women more than men: results of the Lung Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:973–979. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, Azzoli CG, Berry DA, Brawley OW, et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA. 2012;307:2418–29. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, Field JK, Jett JR, Keshavjee S, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wender R, Fontham ET, Barrera E, Jr, Colditz GA, Church TR, Ettinger DS, et al. American Cancer Society lung cancer screening guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:107–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphrey LL, Deffebach M, Pappas M, Baumann C, Artis K, Mitchell JP, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: a systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:411–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-6-201309170-00690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moyer VA U S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services task Force recommendation statement. Ann Inter med. 2014;160(5):330–8. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birim O, Kappetein AP, Takkenberg JJ, van Klaveren RJ, Bogers AJ. Survival after pathological stage IA nonsmall cell lung cancer: tumor size matters. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1137–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strand TE, Rostad H, Moller B, Norstein J. Survival after resection for primary lung cancer: a population based study of 3211 resected patients. Thorax. 2006;61:710–715. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.056481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstraw P, Crowley JJ. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer International Staging Project on lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:281–286. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rami-Porta R, Ball D, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the T descriptors in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:593–602. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31807a2f81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rusch VW, Crowley J, Giroux DJ, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the N descriptors in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:603–612. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31807ec803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Postmus PE, Brambilla E, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for revision of the M descriptors in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:686–693. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31811f4703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groome PA, Bolejack V, Crowley JJ, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: validation of the proposals for revision of the T, N, and M descriptors and consequent stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:694–705. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812d05d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7. Chicago: Springer-Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collaborative Stage Work Group of the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Published by American Joint Committee on Cancer. Chicago, IL: [Accessed August 15, 2013]. Collaborative Stage Data Collection System User Documentation and Coding Instructions, version 02.04.40. Available from: http://cancerstaging.org/cstage. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young JL Jr, Roffers SD, Ries LAG, Fritz AG, Hurlbut AA, editors. SEER Summary Staging Manual - 2000: Codes and Coding Instructions. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2001. NIH Pub. No. 01-4969. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6. Chicago: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fritz A, Jack A, Parkin DM, et al. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Rami-Porta R, et al. Visceral pleural invasion: pathologic criteria and use of elastic stains: proposal for the 7th edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1384–1390. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818e0d9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. [Accessed April 8, 2013];Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards. Available at: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/fords/FORDS_for_2010d_05012010.pdf.

- 27.Kato H, Kawate N, Kobayashi K. The Japan Lung Cancer Society: Classification of lung cancer. 1. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mountain CF, Dresler CM. Regional lymph node classification for lung cancer staging. Chest. 1997;111:1718–1723. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanashiki M, Satoh H, Ishikawa H, Ohtsuka M, Sekizawa K. Outcome of patients with lung cancer detected incidentally. Oncol Rep. 2004;12:945–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mountain C, Libshitz H, Hermes K. Lung cancer handbook for staging and imaging. 3. Houston: Clifton F. Mountain Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sculier JP, Chansky K, Crowley JJ, Van Meerbeeck J, Goldstraw P. The impact of additional prognostic factors on survival and their relationship with the anatomical extent of disease expressed by the 6th edition of the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors and the proposals for the 7th edition. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:457–466. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31816de2b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]