Abstract

How can we explain exceptional advancement by disadvantaged immigrants’ children? Extending segmented assimilation theory, this article traces the structural and relational attributes of high schools attended by young adults who reached their late twenties in 2000. Hypotheses are derived from theories in sociology of education and tested with four waves of data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS). The authors offer three major findings. First, an overwhelming majority of disadvantaged students attend public schools; some relational attributes are typical in public schools attended by disadvantaged students. Second, children’s upward mobility is shaped by the structural and relational attributes of their high schools. Most school effects are the same for disadvantaged and advantaged youngsters, and student-educator bonds and curriculum structure have even stronger positive effects for the disadvantaged. Finally, mobility patterns differ widely among Chinese, Mexicans, and whites. Mexicans are less likely to be exposed to favorable school attributes.

Keywords: immigrant children, upward mobility, high school effects, segmented assimilation, immigrants and education, structural and relational attributes, Mexican, Chinese

As large immigrant flows to the United States continue primarily from Latin America and Asia, the socioeconomic assimilation of newcomers into mainstream society becomes a critical issue. Today, immigrants face a bifurcated labor market that limits ascent to middle-level occupations (Portes and Zhou 1993). Most Hispanic and a substantial proportion of Asian adult immigrants are unskilled laborers. Can children of immigrant parents in low social positions achieve upward mobility? If so, what are the conditions under which upward mobility occurs?

A large body of literature on immigrants’ children concerns educational outcomes in secondary schools, in part because most children of post-1965 immigrants had not reached young adulthood when those studies were conducted. While academic achievement; school abandonment; and other cognitive, behavioral, and emotional outcomes in secondary schools are important, they do not directly speak to social mobility. Since a large proportion of immigrants’ children are now reaching young adulthood, it is timely to examine outcomes such as educational attainment, fields of postsecondary study, and attachment to the labor force. These outcomes not only indicate relative social positions among young adults but also predict future earnings and occupational prestige—key indicators of assimilation.

Immigrants are more likely to be disadvantaged than natives. The reception of immigrants by the U.S. government, the American population, and the local labor market can be positive, neutral, or negative, depending on national origins. Families, coethnic communities, and schools can facilitate or hinder the cognitive and social development of disadvantaged immigrants’ children (Portes and Fernández-Kelly 2008 [this volume]; Zhou et al. 2008 [this volume]). The school is the least studied of these factors. In this article, we identify school attributes that foster upward mobility among disadvantaged immigrants’ children.

Our research advances the understanding of intergenerational mobility in three ways. First, earlier work on the subject focuses on socioeconomic status attainment in full adulthood (Featherman and Hauser 1978). We extend that tradition to focus on an earlier life stage that precedes full adulthood, thus helping unpack the black box of intergenerational mobility. Second, social mobility is often characterized by vertical differentiation; often ignored is horizontal differentiation, which is salient in postsecondary studies. For example, different fields of study among college graduates have profound effects on earnings and occupational prestige. Our study treats fields of postsecondary study as a dimension of social mobility, particularly for young adults who are laying the foundations for their work life. Third, intergenerational mobility is shaped by the socialization of the young in the family, school, and community. However, the literature on social mobility has not addressed the school as a socialization agent. Our study fills this gap.

This study takes a quantitative approach, supplemented by summary descriptions of individual cases. We use the National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS: 88) that followed a nationwide representative sample of eighth-grade students for twelve years from 1988 to 2000 until they were aged twenty-six or twenty-seven. We ask, What school attributes raise young people’s social position? Do disadvantaged students benefit from school attributes as much as advantaged students? How do disadvantaged immigrant children differ in their schooling experience and subsequent status attainment? Together, our quantitative analysis and summary description of individual cases illustrate similarities and differences in the effects of the school on social mobility among low- and high-socioeconomic-status (SES) students of white, Mexican, and Chinese backgrounds.

The Role of the School in Assimilation and Social Mobility

According to Portes and Zhou (1993), lower class position and minority status make immigrants’ children vulnerable to downward assimilation through the influence of inner-city school peers who react to discrimination by rejecting education and other normative paths to upward mobility. Parents’ human capital, family structure, and mode of reception can shield children from downward assimilation. Similarly, strong coethnic communities may protect children from negative peer influence (Zhou and Bankston 1998). Building on segmented assimilation theory, we highlight the importance of school, where children spend a large amount of their waking hours. Variations in school attributes within public and private schools may influence upward mobility among disadvantaged children. We propose that the positive structural and relational aspects of schools can help overcome the obstacles faced by disadvantaged children.

Previous literature on the new second generation highlights the importance of parental human capital, family structure, and modes of incorporation (e.g., Kao and Tienda 1995; Hao and Bonstead-Bruns 1998; Portes and Rumbaut 2001), school peer influences (e.g., Portes and Zhou 1993; Portes and MacLeod 1996), and community and neighborhood (e.g., Zhou and Bankston 1998; Pong and Hao 2007). In their comprehensive study of immigrants’ children, Portes and Rumbaut (2001) stress the pivotal role of external support beyond the family in fostering upward mobility among immigrants’ children. “Significant others” are key factors connecting disadvantaged students to the institutional resources of schools and communities (Stanton-Salazar and Dornbusch 1995; Portes and Fernández-Kelly 2008). Less attention has been paid to school curricula, college-bound programs, and student-educator relations in public schools.

Individuals’ status attainment is typically measured by their occupational prestige, income earned, and years of schooling completed. Rapid technological advance in the new economy places a premium on high-tech skills. This, in turn, turns fields of study into significant paths leading to differing slots in the labor force (Grogger and Eide 1995). Specialty training matters because it has strong implications for youngsters’ occupational attainment in full adulthood. Thus, conceptualizations of the “social position” of young adults should include specialty training in fields of postsecondary study.

There may be concerns about whether young adulthood can fully capture the social mobility of the disadvantaged, who may take longer to achieve than the advantaged. The life course perspective suggests the importance of age-appropriate, on-track transitions (e.g., earning a bachelor’s degree in engineering by age twenty-six) in initiating a full potential for growth, whereas a delayed, off-track transition can only realize part of that growth (Elder 1998). Economic studies about sources of lifetime inequality (Huggett, Ventura, and Yaron 2007) find that, at age twenty, differences in initial conditions account for more of the variation in lifetime earnings and wealth than do differences in growth over a lifetime. Among initial conditions, variations in human capital are most important.

The Role of the School in Student Outcomes

Because middle and high school academic outcomes predict postsecondary education attainment (Adelman 1999, 2006), we draw on the sociology of education literature to understand the social mobility of disadvantaged immigrants’ children. The school as an institution has two salient aspects: structure and social relations. Structural features include sector (public, Catholic, and other private schools), curriculum (tracking, ability grouping, and content), specific programs (college-bound for all students and for disadvantaged students in particular), and other attributes (enrollment size and demographic composition). Relational attributes include collective responsibility (teachers and administrators sharing responsibility for student learning), academic standards, and student-educator bonds (teachers’ interest in students’ learning and college attendance). Schools’ structural and relational aspects differ not only when comparing sectors but also when comparing schools within the same sector. These variations affect students’ opportunity to learn.

Sectors stratify schools and produce different student outcomes by offering varying learning opportunities. Much research has focused on the advantages provided by Catholic schools. Practices and policies in those schools—strong content curriculum, strict discipline, communal spirit—are conducive to student learning (Hoffer, Greeley, and Coleman 1985), as are teachers’ beliefs that all students can learn in challenging courses (Bryk, Lee, and Holland 1993). Sector differences in the composition of ability groups, determinants of placement, and cross-group mobility largely explain the superior academic achievement of Catholic school students. For example, in Catholic schools, most students are placed in the regular-level ability group while only a small proportion of students are placed in either the advanced or low-level ability group. By contrast, public school students are distributed evenly in advanced, regular, and low-level ability groups. Some argue that the higher achievement of Catholic school students may be attributed to selection factors, such as high-SES family background and rigid Catholic school admission standards. However, a recent study using the propensity-score matching method finds that Catholic school unambiguously enhances students who have lower propensity to self-select into such schools (Morgan 2001).

Before the 1980s, tracking in secondary schools was ubiquitous. Students were separated by achievement or ability for instruction. This created and supported educational inequality on the basis of race/ethnicity and social class (Oakes 1985). Concomitant with the decline of de jure tracking over the past two decades, de facto tracking has emerged. Nearly half of students in public schools are still taking different courses in similar subjects (Lucas 1999).

What courses students take greatly affects their academic success (Stevenson, Schiller, and Schneider 1994) because courses vary by academic content and expectations for performance. Because the structure of the curriculum determines course availability and sequence, disadvantaged students are especially harmed by a highly differentiated curriculum. Narrow curricula and strong academic focus that benefit low-income and minority students (Lee and Smith 1993) are typical in Catholic schools. Public schools with similar attributes tend to be more successful than other public schools (Bryk, Lee, and Holland 1993). When the curriculum is highly differentiated, as found in many public schools, diversity in race/ethnicity and SES is more likely to be associated with race- and class-based de facto tracking (Lucas and Berends 2002). Public school students are more likely to be de facto tracked than those in private schools.

Institutions serving an affluent and able clientele tend to offer rigorous and enriched programs of study. Demographic diversity within schools may create inequality of access to advanced courses. For these reasons, studies of student performance often control for school demographic composition, such as aggregate SES and proportion of racial, ethnic, and language minorities. High schools with a large enrollment may alienate and discourage students from learning (Bryk, Lee, and Holland 1993; Lee and Smith 1996; Rosenholtz 1991). Although some push for downsizing schools (National Association of Secondary School Principals 1996), others stress the resources and opportunities available in large schools (Schneider, Wyse, and Keesler 2006–2007).

The relational attributes of schools have long been recognized as important factors affecting student achievement. The expectations of institutional agents, like teachers, counselors, and principals, influence students’ motivation to learn. Pallas et al. (1994) find that teachers view students in high-ability groups as more competent than those in low-ability ones. When low expectations are conveyed to students, their self-esteem diminishes and their motivation decreases. Catholic schools are successful in educating disadvantaged children because they have high expectations even for students in low-ability groupings. Teachers’ expectations notwithstanding, the emotional bonds between teachers/counselors and students are crucial to engage and motivate youngsters. Conceptualizing such emotional bonds as a form of social capital, Stanton-Salazar and Dornbusch (1995) find that within-school social capital is not as critical to students with middle- to high-income backgrounds as it is to their lower-income counterparts who do not have parents to help them access resources in school.

In schools characterized by “collective responsibility”—that is, when school personnel share accountability for youngsters’ total development—student outcomes tend to be better than in schools with low levels of collective responsibility (Lee, Smith, and Croninger 1997). In schools with high collective responsibility, teachers tend to have greater job satisfaction and higher morale, and students are less likely to cut classes or drop out. Greater collective responsibility for learning increases gains for everyone, and more so for low-SES students. In addition, high academic standards have positive effects for everyone (Bryk and Driscoll 1988; Bryk, Lee, and Holland 1993; Lee and Smith 1993, 1996; Lee, Smith, and Croninger 1997).

As a whole, research on schools as institutions stresses structural and relational attributes. Such attributes govern the capacity of students to participate and make progress in learning. Day-to-day school experiences accumulate and shape students’ academic outcomes in high school and their access to and performance in postsecondary institutions.

Hypotheses

We contend that schools have a long-lasting influence on individuals’ life chances and propose two hypotheses. First, positive structural and relational attributes of schools influence students’ social position in young adulthood. We conceptualize positive school attributes as lesser racial or class differentiation, academically rigorous curricula, regular and advanced curricula provided to most students, strong sense of collective responsibility, high academic emphasis, and robust student-educator bonds. Second, positive structural and relational attributes of schools should benefit every student regardless of family background. We also determine empirically which positive structural and relational attributes benefit students from disadvantaged backgrounds more than their advantaged counterparts.

Because of the small sample size of disadvantaged immigrant children in NELS, we are unable to test statistically whether such children gain more benefits from mobility-promoting school attributes than do other students. Instead, we resort to summary descriptions of individual cases of disadvantaged students of Mexican and Chinese origins.

Data and Measures

Our analysis draws from four waves of data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS: 88). The NELS base year survey provides information on country of origin, date of arrival, generational status, family background, and academic background in 1988 when students were in the eighth grade. The first follow-up survey in 1990 provides information about the respondent’s high school. The second follow-up survey in 1992 contains measures of college-bound programs and relational attributes of twelfth-grade schools as well as students’ position in the curriculum structure. To gauge the long-term effect of high schools, we use data from the fourth follow-up survey of 12,144 respondents in 2000. Available information includes educational attainment, fields of postsecondary study, and employment status. By 2000, most respondents were aged twenty-six or twenty-seven. These data suit our purposes given the twelve-year follow-up of a large national sample, which includes a subsample of immigrants’ children.

We consider students as disadvantaged if their parents had very low socioeconomic status in eighth grade: specifically, if the family SES was below the 20th percentile and the parents had less than twelve years of schooling. This restrictive definition of disadvantage pertains to only 1,045 cases (8.6 percent) of the 2000 NELS sample. We focus on three dimensions of a young adult’s social position:

Educational attainment that vertically differentiates young adults’ potential productivity in the labor market. We specify four levels of school attainment—no postsecondary education, some college without a degree, associate’s degree or certificate, and bachelor’s degree and above. We do not further differentiate educational attainment below postsecondary education because postsecondary education is now the standard for economic well-being.

Field of postsecondary study among those who gained a postsecondary degree. If we differentiate workers horizontally, field of postsecondary study predicts individual future earnings and occupational prestige. We highlight two major fields: science and engineering (se) and business and professional (bp). All other fields are grouped in a third category.

Employment status (working or not working) among those without a postsecondary degree. Because of the rising demand for postsecondary education, we omit labor force attachment among those with postsecondary degrees in this analysis.

Combining these three dimensions, our dependent variable is an ordinal variable of ten categories from low to high: no postsecondary education, not working (nopse-nowk); no postsecondary education, working (nopse-wk); some college, not working (sc-nowk); some college, working (sc-wk); associate’s degree or certificate, other fields (aa/ct-ot); associate’s degree or certificate, business or professional fields (aa/ct-bp); associate’s degree or certificate, science and engineering fields (aa/ct-se); bachelor’s degree or higher, other fields (ba-ot); bachelor’s degree or higher, business or professional fields (ba-bp); and bachelor’s degree or higher, science and engineering fields (ba-se).1

Students enter high school with factors (family background, individual demographics, and academic background) that influence their high school learning and preparation for postsecondary education. We measure those features in eighth grade. Students’ social class is indicated by their parents’ SES, which, in NELS, is a standardized composite variable based on parental education, income, and occupation. For immigrants’ children, country of origin and generation status are important. We combine race, ethnicity, and country of origin to construct an eleven-category variable (with an extra category to indicate missing national origin). Given the smaller proportion of whites and blacks among immigrant children, we include all whites in a category and all blacks in another category. Among Hispanics, we identify Mexicans, Cubans, Puerto Ricans, and other Hispanics. Among Asians, we identify Chinese, Filipino, Korean, and other Asians. Mexicans (n = 946), Chinese (n = 165), and Filipinos (n = 140) are the three largest national-origin groups.

In multivariate analysis, we include all groups. In our descriptive analysis and summary descriptions, we highlight Mexican and Chinese because very few Filipinos (four) and no Cubans fit our definition of disadvantage. The first generation refers to foreign-born children with foreign-born parents; the second generation includes children born in the United States with at least one parent born abroad. Third or higher-order generations are native-born children with native-born parents.

Students’ high school learning is also conditioned by their academic preparation and motivation, which is commonly measured by previous achievement. Thus, we use grade retention up to eighth grade to indicate lack of academic preparation. Students’ own educational expectations in eighth grade capture their motivation before entering high school.

We measure a set of school structural variables in the tenth grade. School sectors distinguish between public and Catholic or other private schools. School demographic composition includes percentage of language minorities and percentage of students participating in the free or low-cost lunch program. The location of school can be urban, suburban, and rural. Curriculum content is measured by the number of regular math courses offered. Another set of school structural variables is measured in twelfth grade. Students’ position in the curriculum structure is measured in twelfth grade because that information is not available for the tenth grade. Students reported whether they were placed in a college preparation program, regular program, or vocational program. In addition, programs of college information dissemination and application assistance capture systematic arrangements in schools. We also include the level of participation in federally funded programs that promote college attendance of disadvantaged students, such as Upward Bound and the Talent Search programs.2 We create a composite to measure the level of student involvement in such endeavors.

We also measure a full set of school relational variables in tenth grade. School collective responsibility is a composite based on 5-point scale answers to eleven questions for teachers, such as “I can get through to the most difficult student,” “Teachers are responsible for keeping students from dropping out of class and school,” and “I would change approach if students are not doing well.” We use the school mean of this composite to tap the level of collective responsibility and its standard deviation to control for the variation of teachers’ responsibility in student learning. “Academic press,” a phrase used in the education literature (e.g., Lee and Bryk 1988), refers to the academic climate fostered by the school and teachers to emphasize a high standard for student achievement. It is a composite based on several 5-point scale answers to five items for school administrators, such as “Teachers press students to achieve,” “Students are expected to do homework,” and “Teacher morale is high.” (For details of the composites of collective responsibility and academic press, see Lee, Smith, and Croninger 1997.) Information on collective responsibility and academic press is unavailable for the twelfth grade. The variables describing student-educator bonds are constructed from students’ reports on teachers’ interest in the student’s learning and the level of encouragement offered by educators for college education. These two variables are measured in both tenth and twelfth grades.

Analytic Strategies

We use a quantitative approach supplemented with descriptions of individual cases of disadvantaged immigrant students taken from NELS. The descriptive analysis documents social mobility patterns of disadvantaged students of white, Mexican, and Chinese origin. We then analyze the associations between patterns of structural and relational attributes of high schools and status attainment in young adulthood.

The observed relationship between school attributes and social mobility may be confounded with family background because the latter influences school selection. In addition, the structural and relational attributes of the school may be correlated and confound each other. To test our hypotheses regarding the role of the school in young adults’ social mobility, we use an ordered logit model to analyze the ordinal ten-category dependent variable. For individual i, let Bi denote a vector of background variables (family background, individual demographics, and academic background); S10i denote tenth-grade school variables, S12i denote twelfth-grade school variables, and Cki denote the cumulative probability of mobility for each category of the dependent variable, k = 1, …, 9. The ordered logit model is expressed as

| (1) |

We estimate equation (1) with a set of incremental models by entering subsets of each block of variables sequentially to aid our understanding of the degree to which these variables are confounded.

Equation (1) is the main-effect model where we assume that the school institution effects are the same for the whole population, regardless of their disadvantaged status. To test whether the identified mobility-promoting institutional arrangements more strongly benefit disadvantaged than advantaged students, we specify an indicator for disadvantaged status Di and the interaction terms between this indicator and selected school variables. The interaction-effect models enable us to test our hypotheses regarding differential school effects by disadvantaged statuses.

As with all follow-up longitudinal surveys, missing data is a persistent problem that is even more prominent in a study like ours where many variables (more than eighty original variables and forty-eight constructed variables) at different levels (individual, family, and school) are involved. NELS does a relatively good job in making the sample in each wave representative for the study population with appropriate longitudinal weights. The complete sample for the 2000 wave (fourth follow-up) is 12,144. However, only student ID and gender have no missing values; all other original variables have small to moderate missing cases ranging from 2.7 percent (e.g., age) to 15.7 percent (e.g., students’ placement in curriculum structure).

We adopt a state-of-the-art multiple imputation technique to account for missing data (Rubin 1987; Royston 2004). Traditional imputation typically replaces missing values with the mean, mode, or regression prediction based on nonmissing values. That approach is now regarded as inadequate. For statistical inference to be valid, it is essential to include the correct amount of randomness into the imputations and to incorporate that uncertainty when computing standard errors and confidence intervals for parameters of interest. In multiple imputations, missing observations are assumed to be missing at random. Multiple imputation takes an iterative procedure in which each variable is imputed based on complete cases, and the imputed values of this variable are used in the next variable. This procedure is carried on until all missing values are imputed.3

The basic idea of data analysis with multiple imputations is to deal with missing data by random draws from the multivariate probability distribution of variables in the data. Instead of only one sample, multiple imputations create a number of simulated versions of the sample, each of which contains imputed values for the missing cases and is analyzed separately. In this study, we use five such samples. Estimated parameters for a particular variable are averaged to give a single estimate. Standard errors are computed according to the “Rubin rules,” devised to allow for the between- and within-imputation components of variation in the parameter estimates.4

Descriptive Results

Young adult outcomes

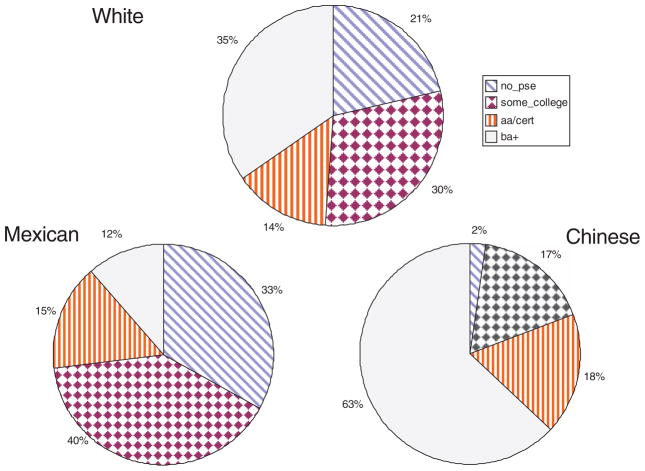

Racial/ethnic disparities in social position among young adults in our data reflect racial divides but also reveal many nuances. Here, we focus on the two largest immigrant groups, Mexican-origin and Chinese-origin, and compare them with whites. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of one dimension of social position—educational attainment. Among those with postsecondary education, the racial/origin divide is sharp by the late twenties: 37 percent of whites, 12 percent of Mexicans, and 63 percent of Chinese had received a bachelor’s degree or above. However, the percentage of associate’s degrees or certificates does not differ as much: 14 percent for whites, 15 percent for Mexicans, and 18 percent for Chinese. A large percentage (40 percent) of Mexicans had some college education without a degree, compared with 30 percent of whites and 17 percent of Chinese. The percentage of our longitudinal sample of respondents without postsecondary education is larger for Mexicans (33 percent) than either whites (21 percent) or Chinese (2 percent).

FIGURE 1. EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT AMONG WHITE, MEXICAN, AND CHINESE YOUNG ADULTS.

NOTE: View the slices from 12 o’clock, clockwise. no_pse = no postsecondary education; aa/cert = associate’s degree or certificate; ba+ = bachelor’s degree or above.

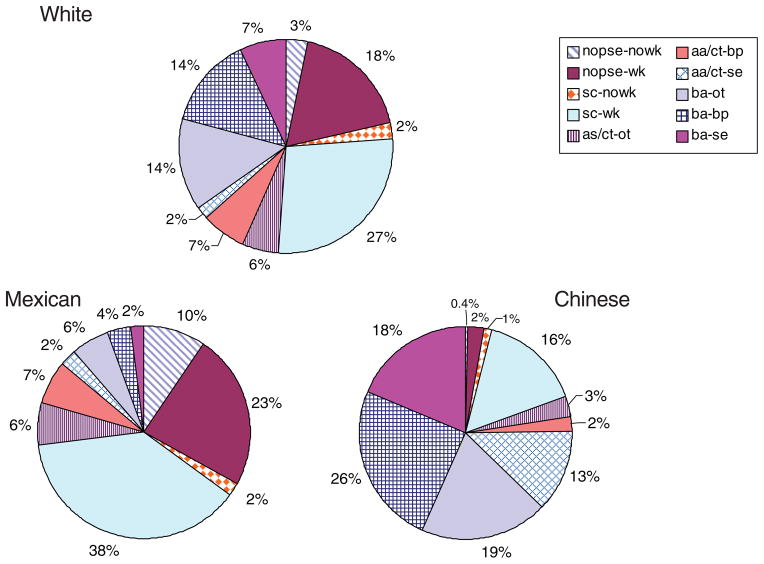

Social position is determined by more than educational attainment. For young adults, specialty training for the higher educated and workforce attachment for the lower educated are key to human capital accumulation. Figure 2 shows that labor force detachment among people without a postsecondary education is low (3 percent of whites, 10 percent of Mexicans, and zero among Chinese). The relative proportion of labor force detachment within the some-college group is very small and similar for all three groups. Chinese with an associate’s degree or certificate account for a relatively high percentage in science and engineering (13 percent). Among college graduates, a similar percentage distribution of study fields is found between whites and Mexicans, who have a smaller proportion in science and engineering than Chinese. Chinese take the lead in providing 18 percent of their group for the science and engineering fields, as compared to 7 percent of whites and 2 percent of Mexicans.

FIGURE 2. THREE-DIMENSIONAL SOCIAL POSITION AMONG WHITE, MEXICAN, AND CHINESE YOUNG ADULTS.

NOTE: View the slices from 12 o’clock, clockwise. Categories are no postsecondary education, not working (nopse-nowk); no postsecondary education, working (nopse-wk); some college, not working (sc-nowk); some college, working (sc-wk); associate’s degree or certificate, other fields (aa/ct-ot); associate’s degree or certificate, business or professional fields (aa/ct-bp); associate’s degree or certificate, science and engineering fields (aa/ct-se); bachelor’s degree or higher, other fields (ba-ot); bachelor’s degree or higher, business or professional fields (ba-bp); and bachelor’s degree or higher, science and engineering fields (ba-se).

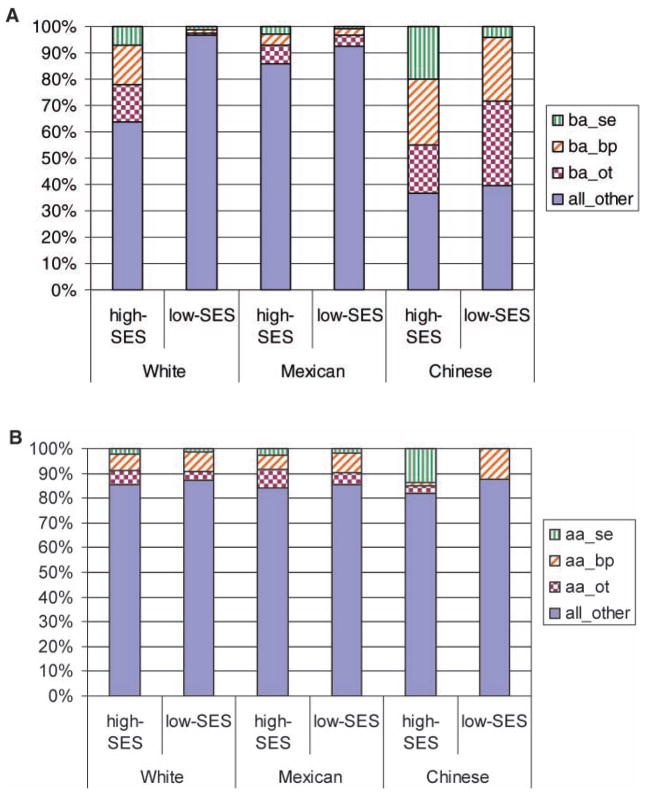

We are interested in how disadvantaged students advance or fail to advance from their parents’ low socioeconomic status. Figure 3 compares educational attainment and fields of study between the disadvantaged and the advantaged among whites, Mexicans, and Chinese. Figure 3(a) is for bachelor’s degree or above (BA) and 3(b) for associate’s degree or certificate (AA/Ct). The top three sections of each bar indicate the proportions of the three types of fields and the bottom section combines all those whose education is lower than BA.

FIGURE 3. FIELDS OF STUDY AMONG WHITE, MEXICAN, AND CHINESE YOUNG ADULTS: (A) BACHELOR’S FIELDS OF STUDY BY SES BACKGROUND; (B) ASSOCIATE’S/CERTIFICATE FIELDS OF STUDY BY SES BACKGROUND.

NOTE: ba_se = bachelor’s degree or higher, science and engineering fields; ba_bp = bachelor’s degree or higher, business or professional fields; ba_ot = bachelor’s degree or higher, other fields; aa_se = associate’s degree or certificate, science and engineering fields; aa_bp = associate’s degree or certificate, business or professional fields; aa_ot = associate’s degree or certificate, other fields. SES = socioeconomic status.

Figure 3(a) shows that the difference in BA and fields of study between low SES and high SES is most striking for whites and least for Chinese. Although Mexicans as a whole exhibit a lower level of college graduation, disadvantaged Mexican students are more likely than disadvantaged white students to earn a bachelor’s degree. It is likely that immigrant drive profoundly conveyed in Portes and Fernández-Kelly (2008) is operating among the disadvantaged. Interestingly, low-SES students of both Mexican and Chinese groups are less likely to study science and engineering than business or other fields, suggesting that the study of science and engineering is associated more with SES than with race/ethnicity. Science and engineering subjects require a strong math background. Our results question the popular belief that Asians tend to be uniformly good at math. Rather, math skills appear to be related to family SES.

Figure 3(b) shows very different SES subpatterns among AA/Ct grantees. The proportion of AA/Ct grantees is similar between low-SES and high-SES for whites and Mexicans but lower for low-SES than high-SES among Chinese. For low-SES AA/Ct grantees of all three groups, business and professional fields are most attractive, particularly for Chinese, as compared with their high-SES counterparts.

Background characteristics

What background characteristics do students bring into high school? Table 1 lists the distribution of background variables by SES within three racial-origin groups. We find substantial differences in the distribution of generational status. While the overwhelming majority of whites are third or higher generation for both high- and low-SES statuses, about 60 percent of high-SES Mexicans and only 17 percent of low-SES Mexicans are third or higher generation. Among Chinese, few are third generation and the majority are first generation, regardless of high- or low-SES status. Overall, the vast majority of low-SES Mexican and Chinese students are first or second generation.

TABLE 1.

WEIGHTED DISTRIBUTION OF FAMILY AND ACADEMIC BACKGROUNDS: BY THREE GROUPS AND LOW SES

| Variable | White

|

Mexican

|

Chinese

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High SES | Low SES | High SES | Low SES | High SES | Low SES | |

| First generation | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.073 | 0.303 | 0.509 | 0.764 |

| Second generation | 0.045 | 0.034 | 0.330 | 0.526 | 0.397 | 0.236 |

| Third or higher generation | 0.947 | 0.952 | 0.597 | 0.171 | 0.094 | 0.000 |

| SES in eighth grade | 0.125 | −1.329 | −0.413 | −1.363 | 0.296 | −1.314 |

| Male | 0.503 | .478 | 0.503 | 0.371 | 0.618 | 0.399 |

| Age | 26.3 | 26.9 | 26.4 | 26.6 | 26.3 | 26.7 |

| Ever repeated a grade | 0.153 | 0.425 | 0.189 | 0.321 | 0.076 | 0.050 |

| Student expectation in eighth grade | 15.6 | 13.7 | 15.1 | 14.3 | 16.1 | 15.9 |

| Observations | 7,924 | 398 | 608 | 338 | 151 | 14 |

| Percentage Low SES | 5.23 | 40.21 | 8.74 | |||

SOURCE: Authors’ compilation based on National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS; 1988–2000). SES = socioeconomic status.

Turning to the SES composite, although we find little group differences in the mean SES of the low-SES category, the mean SES in the high-SES category is highest for Chinese and lowest for Mexicans, reflecting the unique low human capital and negative mode of incorporation among Mexican parents (Portes and Rumbaut 2001). The gender distribution is uneven among low-SES students: many more women than men, especially for Mexican and Chinese groups. A possible explanation is that low-SES male students, particularly minorities, are more likely to be drawn to delinquent activities and drop out of school early. Whether a student ever repeated a grade by eighth grade is greater for low-SES students than for high-SES students among whites and Mexicans but not Chinese.

Distribution of high school variables

Students of different socioeconomic backgrounds are exposed to different school environments (see Table 2). In tenth grade, white students in the high-SES category are more likely to attend Catholic and other private schools, while the vast majority of low-SES students attended public schools, regardless of their race/ ethnicity (99.2 percent for whites, 98.4 percent for Mexicans, and 100 percent for Chinese). Percentage language minority and percentage lunch program are also class based. We can see the concentration of low-SES Mexican and Chinese students in high language-minority schools. Virtually all low-SES students attend schools with a high proportion of students in the free/reduced-priced lunch program. Curriculum content measured by the number of regular math courses, however, does not exhibit differences between low- and high-SES students within all three racial/origin groups. Regarding tenth-grade school relational attributes, we see that the school mean of collective responsibility is actually lower for high-SES Mexican and Chinese students than for their high-SES counterparts. Similarly, low-SES Mexican and Chinese students are exposed to higher academic press and greater teachers’ interest and educators’ college encouragement. Turning to twelfth-grade school variables, we observe a largely class-based pattern in students’ position in curriculum structure with the exception of Chinese students: more high-SES students are placed in college preparation programs and uniformly more low-SES students are placed in vocational programs. Also, a return to a class-based pattern is observed for twelfth-grade student-educator bonds, which was consistently higher for high-SES students than for low-SES students.

TABLE 2.

DISTRIBUTION OF STRUCTURAL AND RELATIONAL ATTRIBUTES OF SCHOOLS: BY THREE GROUPS AND LOW SES

| Variable | White

|

Mexican

|

Chinese

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High SES | Low SES | High SES | Low SES | High SES | Low SES | |

| Structural in tenth grade | ||||||

| School sector | ||||||

| Public | 0.893 | 0.992 | 0.944 | 0.984 | 0.926 | 1.000 |

| Catholic | 0.062 | 0.008 | 0.033 | 0.014 | 0.040 | 0.000 |

| Private | 0.045 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.034 | 0.000 |

| Language minority | ||||||

| 0 percent | 0.375 | 0.523 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.070 | 0.126 |

| 1–10 percent | 0.534 | 0.354 | 0.354 | 0.158 | 0.503 | 0.320 |

| 11+ percent | 0.091 | 0.124 | 0.608 | 0.813 | 0.427 | 0.555 |

| Lunch program | ||||||

| 0 percent | 0.123 | 0.026 | 0.055 | 0.025 | 0.088 | 0.036 |

| 1–10 percent | 0.436 | 0.321 | 0.188 | 0.064 | 0.460 | 0.253 |

| 11–50 percent | 0.397 | 0.522 | 0.454 | 0.501 | 0.233 | 0.389 |

| 51+ percent | 0.044 | 0.132 | 0.304 | 0.411 | 0.219 | 0.322 |

| Location | ||||||

| Urban | 0.538 | 0.725 | 0.713 | 0.649 | 0.529 | 0.622 |

| Suburban | 0.462 | 0.275 | 0.287 | 0.351 | 0.471 | 0.378 |

| Rural | 0.330 | 0.626 | 0.252 | 0.216 | 0.042 | 0.126 |

| Number of regular math courses | 4.164 | 4.203 | 4.110 | 3.948 | 4.224 | 4.713 |

| Relational in tenth grade | ||||||

| School collective responsibility | ||||||

| School mean | 0.090 | −0.028 | 0.257 | 0.343 | 0.176 | 0.235 |

| School SD | 0.535 | 0.577 | 0.714 | 0.649 | 0.678 | 0.761 |

| School academic press | −0.012 | −0.146 | −0.200 | −0.055 | 0.300 | 0.942 |

| Student-educator bonds | ||||||

| Teachers’ interest | 0.758 | 0.718 | 0.731 | 0.755 | 0.790 | 0.847 |

| Educators’ college encouragement | ||||||

| Low | 0.331 | 0.447 | 0.329 | 0.250 | 0.381 | 0.340 |

| Medium | 0.190 | 0.194 | 0.218 | 0.200 | 0.135 | 0.213 |

| High | 0.479 | 0.359 | 0.453 | 0.550 | 0.484 | 0.447 |

| Structural in twelfth grade | ||||||

| Student position in curriculum structure | ||||||

| College prep | 0.494 | 0.184 | 0.349 | 0.287 | 0.581 | 0.734 |

| Regular | 0.366 | 0.600 | 0.505 | 0.475 | 0.370 | 0.207 |

| Vocational | 0.140 | 0.216 | 0.146 | 0.238 | 0.049 | 0.059 |

| School programs assisting college going | 2.805 | 2.157 | 2.598 | 2.510 | 3.709 | 3.110 |

| Federal programs for disadvantaged | 0.960 | 1.058 | 1.270 | 1.328 | 1.533 | 1.698 |

| Relational in twelfth grade | ||||||

| Student-educator bonds | ||||||

| Teachers interest | 0.822 | 0.810 | 0.846 | 0.843 | 0.863 | 0.794 |

| Educators’ college encouragement | ||||||

| Low | 0.292 | 0.646 | 0.324 | 0.436 | 0.137 | 0.210 |

| Medium | 0.132 | 0.091 | 0.136 | 0.111 | 0.139 | 0.151 |

| High | 0.576 | 0.263 | 0.540 | 0.453 | 0.724 | 0.639 |

SOURCE: Authors’ compilation based on National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS; 1988–2000).

NOTE: SES = socioeconomic status.

Multivariate Results

Effects of background characteristics

Our first multivariate analysis examines race/origin, family and individual background, tenth-grade school variables, and twelfth-grade school variables in four incremental models shown in Table 3. The “race/origin model” (model 1) shows that Cubans are similar to whites. Blacks, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and other Hispanics fare worse than whites, whereas all Asian groups fare better. The negative Mexican effect (−.735) is significantly greater than the negative black effect (−.480), consistent with numerous previous findings about the persistent Mexican disadvantage in educational attainment shaped by parents’ low human capital and negative reception (e.g., Portes and Rumbaut 2001; Perlmann 2005). After family SES, generation status, individual demographics, and academic background are included in the “background model” (model 2), Mexicans’ disadvantage reduces by a half but nonetheless remains sizable and significant. The “tenth-grade school model” (model 3) and the “twelfth-grade school model” (model 4) yield little additional change in race/origin coefficients. The persistent, negative Mexican effect is consistent with previous findings about the impact of negative mode of incorporation of Mexican parents when SES is held constant.

TABLE 3.

EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND ON THREE-DIMENSION SOCIAL POSITION AMONG YOUNG ADULTS

| Variable | Race/Origin (1) | Background (2) | Tenth-Grade School (3) | Twelfth-Grade School (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity/national-origin | ||||

| Black | −0.480*** (0.055) | −0.089 (0.058) | −0.074 (0.060) | −0.118 (0.060) |

| Mexican | −0.735*** (0.059) | −0.327*** (0.071) | −0.279*** (0.075) | −0.312*** (0.075) |

| Cuban | 0.271 (0.221) | −0.067 (0.227) | −0.103 (0.230) | 0.015 (0.233) |

| Puerto Rican | −0.641*** (0.144) | −0.482*** (0.158) | −0.390** (0.160) | −0.299 (0.164) |

| Other Hispanic | −0.226** (0.102) | −0.262** (0.110) | −0.209 (0.111) | −0.164 (0.112) |

| Chinese | 1.299*** (0.137) | 0.609*** (0.156) | 0.696*** (0.158) | 0.579*** (0.161) |

| Filipino | 0.311** (0.149) | −0.490*** (0.161) | −0.429*** (0.163) | −0.547*** (0.167) |

| Korean | 0.951*** (0.174) | −0.208 (0.188) | −0.098 (0.188) | −0.114 (0.186) |

| Other Asian | 0.848*** (0.099) | 0.171 (0.113) | 0.221 (0.114) | 0.236** (0.117) |

| Generation status | ||||

| Second generation | −0.213** (0.090) | −0.223** (0.089) | −0.188** (0.092) | |

| Third or higher generation | −0.705*** (0.085) | −0.698*** (0.089) | −0.638*** (0.094) | |

| Parental SES | 0.859*** (0.026) | 0.783*** (0.029) | 0.680*** (0.029) | |

| Male | −0.030 (0.033) | −0.028 (0.033) | −0.016 (0.034) | |

| Age | −0.101*** (0.034) | −0.100*** (0.034) | −0.044 (0.034) | |

| Ever repeated a grade | −0.733*** (0.057) | −0.718*** (0.057) | −0.495*** (0.059) | |

| Student expectation in eighth grade | 0.256*** (0.010) | 0.235*** (0.010) | 0.163*** (0.010) | |

NOTE: Estimates are based on the full sample of 12,144 respondents. Model 1 enters only race/ethnicity/national origin indicators. Model 2 adds family background, individual characteristics, and academic background. Model 3 adds tenth-grade school variables. Model 4 adds twelfth-grade school variables. Standard errors are in parentheses. SES = socioeconomic status.

Significant at 5 percent.

Significant at 1 percent.

Moving to the bottom panel of Table 3, we notice that the first generation fares better than the second generation, which, in turn, fares better than the third generation. This monotonic decline in mobility provides evidence to support the relationship between “immigrant drive” and time passage in the United States. Soon after arrival, immigrant parents have high expectation for their children and push them to succeed (Portes and Fernández-Kelly 2008). Generational status reflects the length of time the immigrant family has been in the United States. The passage of time brings about relentless acculturation, which progressively weakens immigrant drive (Portes and Rumbaut 2001). These generational effects are fairly stable across incremental models, suggesting that generational status does not confound with school structural and relational attributes. The expected parental SES effect exhibits small and steady declines as tenth- and twelfth-grade school variables are included, suggesting that the school structural and relational attributes are at most only weakly related to social class. We find no gender difference in young adults’ social position, which echoes the increasing empirical evidence that shows the catching up of women with men. However, because our dependent variable consists of three dimensions, women’s edge in educational attainment and their falling behind in science and engineering may cancel each other out.

We contend that early academic background captures readiness for high school learning. Low levels of academic preparedness, indicated by grade repetition and low initial expectations, harm youngsters’ mobility prospects. The strength of academic preparedness is reduced but remains statistically significant even after twelfth-grade school variables are included in the model.

Effects of tenth-grade school variables

The effects of tenth-grade school variables from models 3 and 4 are shown in Table 4. In model 3, Catholic and private schools predict higher social position among young adults. When sectors are controlled, most school structural variables, with the exception of a high percentage of language minorities, do not affect social mobility outcomes. We have also tested and found that other demographic features, such as percentage of whites and percentage of single-parent families, do not matter. A possible reason is that school sector almost overlaps with demographic composition. For instance, no Catholic and private schools have more than 10 percent of students who participate in free or reduced-cost lunch programs. The lead of Catholic and private school, however, disappears as twelfth-grade school variables measuring structural and relational attributions are introduced in model 4.

TABLE 4.

EFFECTS OF TENTH-GRADE SCHOOL STRUCTURAL AND RATIONAL ATTRIBUTES ON THE THREE-DIMENSION SOCIAL POSITION AMONG YOUNG ADULTS

| Variable | Tenth-Grade School (3) | Twelfth-Grade School (4) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural in tenth grade | ||

| Catholic, private (public as the reference) | 0.306*** (0.088) | 0.127 (0.089) |

| Language minority (0 percent as the reference) | ||

| 1–10 percent | −0.051 (0.040) | −0.016 (0.041) |

| 11+ percent | −0.120** (0.060) | −0.119 (0.061) |

| Lunch program (0 percent as the reference) | ||

| 1–10 percent | 0.115 (0.090) | 0.151 (0.092) |

| 11–50 percent | 0.058 (0.091) | 0.112 (0.092) |

| 51+ percent | 0.032 (0.108) | 0.090 (0.111) |

| Location (urban as the reference) | ||

| Suburban | 0.016 (0.045) | −0.001 (0.046) |

| Rural | 0.059 (0.049) | −0.013 (0.051) |

| Number of regular math courses | 0.033 (0.019) | 0.017 (0.022) |

| Relational in tenth grade | ||

| School collective responsibility | ||

| School mean | 0.099** (0.041) | 0.091** (0.041) |

| School SD | −0.063 (0.048) | −0.066 (0.049) |

| School academic press | 0.092*** (0.030) | 0.044 (0.031) |

| Teachers’ interest | 0.261*** (0.039) | 0.114*** (0.042) |

| Educators’ college encouragement | ||

| Medium | 0.129*** (0.049) | −0.029 (0.051) |

| High | 0.352*** (0.040) | 0.067 (0.043) |

NOTE: Estimates are based on the full sample of 12,144 respondents. Models 3 and 4 include race/national-origin, family background, individual characteristics, and academic background. Model 3 enters tenth-grade school variables in three steps. Model 4 adds twelfth-grade school variables. Standard errors are in parentheses.

Significant at 5 percent.

Significant at 1 percent.

As hypothesized, a strong sense of collective responsibility among teachers significantly improves students’ social position at young adulthood. Also as hypothesized, strong academic press is positively associated with higher social position in young adulthood. Whether teachers are interested in a student’s learning and whether teachers and counselors encourage the student to pursue a college education promote the fortunes of young adults.

Thus, results from model 3 show the important role of tenth-grade education. Although public schools as a whole fall behind Catholic or private schools in promoting future social positions, high levels of collective responsibility and academic press in public schools can reduce differences in mobility outcomes between school sectors. In addition, student-educator bonds play an independent, yet important role in transmitting institutional resources to students and neutralizing sectoral differences. Good relational attributes in a public school can brighten students’ futures. This is especially significant for low-SES students.

The significant effects of many of the tenth-grade school variables, except collective responsibility and teachers’ interest, are overridden by twelfth-grade school variables. The reason is that students’ placement in the twelfth-grade curriculum structure is largely determined by the tenth-grade school factors. In addition, educators’ college encouragement is more closely related to college decision in twelfth grade than in tenth grade.

Effects of twelfth-grade school variables

Estimates for twelfth-grade school variables from model 4 are shown in Table 5. Placement of students in upper tracks should have a clear consequence for their high educational attainment and the field of study. That is what we found. The premium of the college preparation program is especially strong. College-bound programs also have a promoting effect. Federal programs for the disadvantaged such as Upward Bound have an overall small negative effect. The student-educator bond variables in twelfth grade are important for young adult outcomes, stronger than the effects of these variables in tenth grade.

TABLE 5.

EFFECTS OF TWELFTH-GRADE SCHOOL STRUCTURAL AND RELATIONAL ATTRIBUTES ON THREE-DIMENSION SOCIAL POSITION AMONG YOUNG ADULTS

| Variable | Twelfth-Grade School (4) |

|---|---|

| Structural in twelfth grade | |

| Student position in curriculum structure (vocational as the reference) | |

| College prep | 1.103*** (0.054) |

| Regular | 0.356*** (0.049) |

| School programs assisting college going | 0.149*** (0.016) |

| Federal programs for disadvantaged | −0.058** (0.026) |

| Relational in twelfth grade | |

| Teachers’ interest | 0.148*** (0.045) |

| Educators’ college encouragement | |

| Medium | 0.468*** (0.060) |

| High | 0.726*** (0.050) |

NOTE: Estimates are based on the full sample of 12,144 respondents. Model 4 includes race/ethnicity/national-origin indicators, family background, individual characteristics and academic background, and tenth-grade school variables. Standard errors are in parentheses.

Significant at 5 percent.

Significant at 1 percent.

In sum, model 4 (the last column of Tables 3 through 5) shows, first, that Mexican and Filipino students fall behind white students, but Chinese and other Asian students fare better. Second, first-generation students perform better than second-generation students, who, in turn, perform better than the third generation. Third, parental SES remains significantly strong, and academic background and early educational expectations continue to predict young adult outcomes. Fourth, among tenth-grade school variables, collective responsibility and teachers’ interest in student learning remain important predictors. Finally, all twelfth-grade school variables are significant in shaping youth’s future social positions

Differential school effects by disadvantaged status

Do the identified factors differ by SES background? We use model 3 to test the differential effects of tenth-grade school variables, and we use model 4 to test the differential effects of twelfth-grade school variables. No differential effects are found for tenth-grade school sector and demographic composition and twelfth-grade teachers’ interest and educators’ college encouragement. This is an important finding because disadvantaged students can thrive under favorable school attributes.

Table 6 reports results of the interaction between student SES, on one hand, and school’s relational attributes in tenth grade and structural attributes in twelfth grade, on the other. We find significant differential effects for low- and high-SES students along disparate values of school variables. Because of the small number (1,045) of disadvantaged students in our sample (given our strict definition), we consider a statistical level of .10 for testing an interaction effect. Columns 1 and 3 repeat the estimates from the previous main-effect models for comparison. Column 2 reveals that, besides the beneficial high level of student-educator bonds, the educators’ medium level of college encouragement (from either teacher or counselor but not both) is advantageous only for low-SES students. Any external support, even from one teacher, will help transmit institutional resources to low-SES students. As Stanton-Salazar and Dornbusch (1995) suggest, school relations may be the only channel for resource transmission for low-SES students. More generally, this finding is in line with the identification of a “really significant other” as a decisive factor in producing educational success (Portes and Fernández-Kelly 2008).

TABLE 6.

SELECTED INTERACTIVE EFFECTS OF SCHOOL STRUCTURAL AND RELATIONAL ATTRIBUTES AND LOW-SES INDICATOR

| Variable | Tenth-Grade School (3) | (3a) | Twelfth-Grade School (4) | (4a) | (4b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenth grade | |||||

| Teachers’ interest | 0.261*** (0.039) | 0.268*** (0.041) | |||

| Teachers’ Interest × Low SES | −0.082 (0.105) | ||||

| Educators’ college encouragement (medium) | 0.130*** (0.049) | 0.088 (0.050) | |||

| Educators’ College Encouragement (Medium) × Low SES | 0.416*** (0.147) | ||||

| Educators’ college encouragement (high) | 0.352*** (0.040) | 0.333*** (0.041) | |||

| Educators’ College Encouragement (High) × Low SES | 0.175 (0.140) | ||||

| Twelfth grade | |||||

| College prep program | 1.103*** (0.054) | 1.078*** (0.056) | |||

| College Prep Program × Low SES | 0.277* (0.164) | ||||

| Regular program | 0.356*** (0.049) | 0.344*** (0.051) | |||

| Regular Program × Low SES | 0.071 (0.114) | ||||

| School program assisting college-going | 0.149*** (0.016) | 0.151*** (0.016) | |||

| School Program Assisting College-Going × Low SES | −0.047 (0.040) | ||||

| Federal programs for disadvantaged | −0.058** (0.026) | −0.070** (0.028) | |||

| Federal Programs for Disadvantaged × Low SES | 0.146* (0.087) | ||||

NOTE: Estimates are based on the full sample of 12,144 respondents. Models 3 and 4 in this table are the same as those in previous models. Model 3a introduces a set of interaction terms to model 3. Models 4a and 4b introduce interaction terms to model 4 one set at a time. Standard errors are in parentheses. SES = socioeconomic status.

Significant at 10 percent.

Significant at 5 percent.

Significant at 1 percent.

Model 4a shows the bonus effect of being in a college preparatory program for low-SES students (p < .10) and a uniform effect of being in a regular program. Since placement of students in the curriculum structure is often associated with students’ social class, the positive effect of college preparatory programs for low-SES students points to directions for policy intervention. Model 4b in column 5 shows that federal programs for the disadvantaged benefit low-SES students (.146 – .070 = .076), while the negative effect for high-SES students is relatively small. These results provide population-level evidence for the critical role of external support for children whose immigrant parents were negatively received in the host country (see Portes and Rumbaut 2001).

Disadvantaged Immigrants’ Children Who Achieved Upward Mobility: Some Examples

Thus far, we have focused on upward mobility among disadvantaged children at the aggregate level. Nonetheless, we face the problem of small sample size of successful cases from disadvantaged backgrounds. Customized studies such as the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study (CILS) have the same problem (Portes and Fernández-Kelly 2008). Therefore, we use summary descriptions to illustrate major findings from our quantitative analysis. We narrow the scope of success to bachelor’s degrees and lucrative fields of study.

First, we outline the basic mobility patterns for Mexicans and Chinese and compare them with those of third-generation whites. By our definition, the percentage of Mexicans with disadvantaged background (40 percent) was more than four times higher than the percentage for Chinese (9 percent) and about eight times higher than the percentage for whites (5 percent). The rate of gaining a bachelor’s degree among disadvantaged students is about 7 percent for Mexicans, 60 percent for Chinese, and 3 percent for third-generation whites. In comparison, bachelor’s degree rates among the advantaged are 14.3 percent for Mexicans, 63.3 percent for Chinese, and 36.3 percent for third-generation whites. These patterns are generalizable for Mexicans and whites but not for Chinese because the subsample size of disadvantaged Chinese is fourteen, which is too small for statistical use.

From the Mexican and Chinese groups we selected a few students who had a low-SES background but achieved upward social mobility. We present two (out of eleven) successful first-generation Mexicans, one (out of sixteen) successful second-generation Mexican student, and one (out of eight) first-generation Chinese student. No disadvantaged Chinese students are second or third generation.

First-generation Mexicans

Rosa, a Mexican immigrant girl, came to the United States at age four. Neither of her parents completed high school. Her parental socioeconomic status was very low, within the bottom 3 percent of the NELS sample. Rosa had high expectations for college education in eighth grade. Although her English proficiency was low, she did not repeat any grade or take any remedial reading or remedial math courses. Rosa’s tenth-grade high school was public, small, and rural. More than 50 percent of the student body encompassed racial or ethnic minorities, almost all students participated in the free lunch program, and more than 10 percent did not have English proficiency. Despite these adverse conditions, the school exhibited desirable structural and relational attributes: collective responsibility in the top quartile of all NELS schools and academic press in the top quintile. Rosa’s teachers were very interested in her learning, and the school counselor and teachers strongly encouraged her to go to college. In twelfth grade, Rosa was placed in a college preparatory program. Upon graduation, she was admitted to a public four-year university. She majored in business and earned her bachelor’s degree in business management and administration in 1996. In 1999, Rosa became a manager. She feels that she has considerable autonomy and decision-making capacity in her job.

Juan came from Mexico to the United States when he was five years old in 1978. His Mexican parents’ SES was in the 10th percentile of the NELS parental SES distribution. In eighth grade, Juan’s parents hoped that he would graduate from college, and Juan harbored the same hope. Although his English proficiency was low and his reading test score was in the bottom quartile, he did not have to take any remedial English classes and was never held back. At the same time, Juan exhibited high achievement in math, ranking in the 95th percentile. In tenth grade, he entered a public high school in a suburban area. The school was large and diverse in terms of race, SES, and language minorities. Collective responsibility and academic press were at about the median level among NELS schools. The school offered four regular math courses and two Advanced Placement (AP) math courses. Juan’s teachers were very interested in his learning; educators at the school who knew Juan strongly encouraged him to pursue college admission. His expectations grew higher when he was in tenth grade. In twelfth grade, Juan was in a college preparation program. He continued to benefit from strong bonds with teachers and counselors. Upon high school graduation, he was admitted to a four-year public university where he majored in art-speech/drama. He received a bachelor’s degree in 1996. In 2000 Juan was an office manager.

Second-generation Mexicans

Jose was born in the United States in the 1970s. His Mexican immigrant parents’ SES was below the 4th percentile among NELS parents. However Jose and his parents hoped that he would obtain a graduate degree. Born in the United States, he was fluent in English. His eighth-grade test score in reading was above average, but his math score was below the 40th percentile. In 1989, Jose attended a large urban public school. Its curriculum was rigorous, offering five regular math courses and five college-level courses. The school organized college information fairs and provided advice on how to finance a higher education. The school also actively participated in the federally funded Upward Bound Program. In his senior year, Jose was placed in a technical education program, but he also participated in Upward Bound, which nurtured his college aspirations. Teachers collectively held high responsibility. Jose’s teachers in his tenth and twelfth grades had strong interest in his learning. In the twelfth grade, school counselors and teachers strongly supported Jose’s pursuit of a college education. He was admitted to a four-year public university in 1992. He majored in electrical and computer engineering and was awarded a bachelor’s degree in engineering. Jose was a computer system analyst in 2000.

First-generation Chinese

Ying, a five-year-old girl, arrived in the United States from China with her parents in the late 1970s. Without high school education, her parents were in the bottom quintile of the SES distribution. In eighth grade, Ying’s reading and math standardized test scores were above the 80th percentile. Both Ying and her parents expected Ying to earn a graduate-level degree. In 1989, she entered a suburban public high school, where 20 percent of students participated in the free lunch program. The school had a large and diverse student body. The school’s collective responsibility was about average. Academic press, however, was in the top 20 percent among NELS schools. Ying reported that her teachers were very interested in her, and the school counselor and teachers strongly encouraged her to pursue a college education. In twelfth grade, Ying was placed in one of several college preparation programs. Ying’s bonds with her teachers and other educators remained strong in twelfth grade. Upon graduation, Ying was admitted to a four-year public college where she majored in biology. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in biological science. Currently, she is working as a medical practice professional while continuing to pursue a higher degree.

Similarities among cases

A first commonality in these students is their public school attendance. Only 11 out 1,045 disadvantaged students in NELS attended Catholic or private schools. Among 338 low-SES Mexican-origin students who achieved upward mobility, only 3 attended Catholic schools and 1 attended a private school. Thus, by our definition, school sector cannot be a determinant for upward mobility among the disadvantaged. A second commonality is immigrant drive, exemplified by high parental expectations and constant push for children’s academic success. An outstanding similarity, however, entails the structural and relational features of the schools attended by those disadvantaged children—they all experienced a rigorous curriculum, high levels of collective responsibility, strong academic press, college-bound programs, and close bonds with teachers and other educators. Two or more of these conditions served as important forces promoting upward mobility and helping students overcome barriers. Readers can find strong parallels of our selected cases with those described by Zhou et al. (2008).

Conclusion

This study joins others in this volume searching for causes of exceptional advancement among disadvantaged immigrants’ children. Analyzing the social positions of young adults in their late twenties in 2000, we traced upward mobility to the structural and relational attributes of the high schools those students attended. Drawing on theories from sociology of education, we tested hypotheses using four waves of data from NELS. We focused on two immigrant groups—Mexican and Chinese—and compared them with third-generation whites.

Three major findings can be drawn from our analysis. First, an overwhelming majority of disadvantaged students attend public schools. Fortunately, the distribution of favorable school attributes, whether structural or relational, is not entirely based on school sector. School relational attributes are much less likely to vary by students’ social class backgrounds. Some relational attributes are even more accessible to disadvantaged children than to their advantaged counterparts. These patterns suggest that policy intervention should aim at strengthening structural and relational attributes. Second, children’s upward mobility is affected by structural and relational attributes in their high schools. Most school effects are the same for disadvantaged and advantaged students. Student-educator bonds and curriculum structure have even stronger positive effects on disadvantaged students. Finally, we find substantial differences in the mobility patterns of Chinese, Mexicans, and whites. Neither Chinese nor Mexicans show convergence toward whites in young-adult social positions, a result consistent with the observations by Zhou et al. (2008). The large gap between Mexicans and whites is particularly worrisome, because Mexicans make up the largest group of children who have immigrant parents. Although we have identified schools’ structural and relational attributes that can help Mexican children succeed, most Mexican children attend schools that do not have those favorable characteristics. Combined with family disadvantage, this factor suggests that downward mobility among second-generation Mexicans may not be reversed without major policy efforts.

Our study suggests that investing in the structural and relational attributes of public schools is part of the solution for disadvantaged children, regardless of national origin, and especially for Mexicans. The upward mobility of first- and second-generation immigrant students appears to be much more dependent on their experiences in high school than that of their higher-generation counterparts.

Acknowledgments

NOTE: This research was supported by the Spencer Foundation Resident Fellows Program in 2007.

Biographies

Lingxin Hao is a professor of sociology at Johns Hopkins University. Her fields of expertise are immigration, social inequality, family, public policy, and quantitative methodology. She has conducted innovative research on the social mobility of immigrant and native-born populations. Her latest projects focus on immigration and health and the impact of migration on sending countries. She is the author of Color Lines, Country Lines: Race, Immigration, and Wealth Stratification in America (Russell Sage Foundation 2007)

Suet-ling Pong is a professor of education and demography and has a courtesy appointment in sociology at Pennsylvania State University. Her research on sociology of education centers on the relationship between family structure and children’s education, parental practices and involvement, and the education of immigrants’ children. She is the recipient of the Willard Waller Award from the Sociology of Education Section of the American Sociological Association

Footnotes

The order of science/technology (se) or business/professional (bp) is debatable. We use a model-base approach to determine which order is optimal from the data. By comparing the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) from the two ordered logit models for the ten-category dependent variable that switch the se and bp position within associate’s degree and bachelor’s degree, we find that the current order leads to a better fit of the model.

The Department of Education provides discretionary grants to institutions of higher education to work with high schools to generate disadvantaged students’ skills and motivation necessary for success in postsecondary education. Provided services included instruction in reading, writing, mathematics, science, study skills, and other subjects. However, prior evaluations of these programs only found sporadic positive effects on a set of student outcomes (U.S. Department of Education 2004).

Missing values of all variables used in the multivariate analysis are imputed using the multiple imputation technique so that the full sample of 12,144 in the 2000 wave is used in model estimations. By twelfth grade, there were 931 dropouts, among whom only 284 dropped out by tenth grade. Since high school dropouts have high school experience, our multiple imputation applies to high school dropouts if their values on high school variables are missing.

We use the Stata command “ice” to create five multiple imputation samples and “micombine” to produce the estimates and their standard errors.

References

- Adelman Clifford. Answers in the tool box: Academic intensity, attendance patterns, and bachelor’s degree attainment. Washington, DC: National Institute on Postsecondary Education, Libraries, and Lifelong Learning, U.S. Department of Education; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Adelman Clifford. The toolbox revisited: Paths to degree completion from high school through college. Washington, DC: Office of Vocational and Adult Education, U.S. Department of Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk Anthony S, Driscoll Mary E. The school as community: Theoretical foundations, contextual influences, and consequences for students and teachers. Madison: National Center on Effective Secondary Schools, University of Wisconsin; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk Antonia, Lee Valerie E, Holland Peter Blakeley. Catholic school and the common good. Boston: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Elder Glen H., Jr The life course as developmental theory. Child Development. 1998;69 (1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherman DL, Hauser R. Opportunity and change. New York: Academic Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Grogger Jeff, Eide Eric. Changes in college skills and the rise in the college wage premium. Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30:280–310. [Google Scholar]

- Hao Lingxin, Bonstead-Bruns Melissa. Parent-child difference in educational expectations and academic achievement of immigrant and native students. Sociology of Education. 1998;71:175–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer Thomas, Greeley Andrew M, Coleman James S. Achievent growth in public and Catholic schools. Sociology of Education. 1985;58:74–97. [Google Scholar]

- Huggett Mark, Ventura Gustavo, Yaron Amir. Sources of lifetime inequality. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2007. NBER Working Paper no. W13224. [Google Scholar]

- Kao Grace, Tienda Marta. Optimism and achievement: the educational performance of immigrant youth. Social Science Quarterly. 1995;76 (1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lee VE, Bryk AS. Curriculum tracking as mediating the social distribution of high school achievement. Sociology of Education. 1988;61:78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Valerie E, Smith Julia B. Effects of school restructuring on the achievement and engagement of middle-grade students. Sociology of Education. 1993;66:164–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Valerie E, Smith Julia B. Collective responsibility for learning and its effects on gains in achievement for early secondary school students. American Journal of Education. 1996;104:103–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lee VE, Smith JB, Croninger RG. How high school organization influences the equitable distribution of learning in mathematics and science. Sociology of Education. 1997;70:128–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas Samuel Roundfield. Tracking inequality: stratification and mobility in American high schools. New York: Teachers College Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas Samuel R, Berends Mark. Sociodemographic diversity, correlated achievement, and de facto tracking. Sociology of Education. 2002;75:328–48. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Stephen L. Counterfactuals, causal effect heterogeneity, and the Catholic school effect on learning. Sociology of Education. 2001;74:341–74. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Secondary School Principals. Breaking ranks: Changing an American institution. Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes J. Keeping track: How schools structure inequality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pallas Aaron M, Entwisle Doris R, Alexander Karl L, Francis Stluka M. Ability-group effects: Instructional, social, or institutional? Sociology of Education. 1994;67:27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Perlmann Joel. Italians then, Mexicans now: Immigrant origins and second-generation progress, 1890 to 2000. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pong Suet-ling, Hao Lingxin. Neighborhood and school factors in the school performance of immigrants’ children. International Migration Review. 2007;41 (1):206–41. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Fernández-Kelly Patricia. No margin for error: Educational and occupational achievement among disadvantaged children of immigrants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2008;620:12–36. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, MacLeod Dag. Educational progress of children of immigrants: The roles of class, ethnicity, and school context. Sociology of Education. 1996;69:255–75. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Rumbaut Ruben G. The legacies. Berkeley: University of California Press; New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Zhou Min. The new second generation: segmented assimilation and its variants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1993;530:74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenholtz Susan J. Teachers’ workplace: The social organization of schools. New York: Longman; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. The Stata Journal. 2004;4(3):227–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for non-response in surveys. New York: John Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Barbara L, Wyse Adam E, Keesler Venessa. Is small really better? Testing some assumptions about high school size. Brookings Papers on Education Policy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2006–2007. pp. 15–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Salazar R, Dornbusch Sanford M. Social capital and the reproduction of inequality: Information networks among Mexican-origin high school students. Sociology of Education. 1995;68 (2):116–35. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson David L, Schiller Kathryn S, Schneider Barbara. Sequences of opportunities for learning. Sociology of Education. 1994;67:184–98. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. The impacts of regular upward bound: Results from the third follow-up data collection. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Min, Bankston Carl L., III . Growing up American: How Vietnamese children adapt to life in the United States. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Min, Lee Jennifer, Vallejo Jody Agius, Tafoya-Estrada Rosaura, Xiong Yan Sao. Success attained, deterred, and denied: Divergent pathways to social mobility in Los Angeles’s new second generation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2008;620:37–61. [Google Scholar]