Abstract

Aim:

To evaluate and compare the clinical effects of topical subgingival application of 2% whole turmeric gel and 1% chlorhexidine gel as an adjunct to scaling and root planing (SRP) in patients suffering from chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

Fifteen patients with localized or generalized chronic periodontitis with a pocket depth of 5-7 mm were selected. In each patient, on completion of SRP, three non-adjacent sites in three different quadrants were randomly divided into three different groups, that is, Group I: Those receiving 2% turmeric gel, Group II: Those receiving 1% chlorhexidine gel (Hexigel), and Group III: SRP alone (control site). Plaque index, gingival index, probing depth, and clinical attachment levels were determined at baseline, 30 days, and 45 days.

Results:

Group II as a local drug system was better than Group III. Group I showed comparable improvement in all the clinical parameters as Group II.

Conclusions:

The experimental local drug delivery system containing 2% whole turmeric gel helped in reduction of probing depth and gain of clinical attachment levels.

Keywords: Chlorhexidine, chronic periodontitis, turmeric gel

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases in the world, with the primary etiological agent being pathogenic bacteria that reside in the subgingival area.[1]

Conventional periodontal therapy consists of mechanical debridement to disrupt the subgingival microbiota. However, comprehensive mechanical debridement of sites with deep periodontal pockets is difficult to accomplish. This has led to the adjunctive use of antimicrobial agents delivered either systemically or locally. As the systemic use of antimicrobial agents may cause several side effects like hypersensitivity, resistant strains, and superinfections, their local administration has received considerable attention.[2]

Local drug delivery systems allow the therapeutic agents to be targeted to the disease site. Thus, the dose can be minimized, reducing the systemic absorption and subsequent risk of adverse side effects. Higher concentration of a therapeutic agent can be attained in subgingival sites by local drug delivery compared with a systemic drug regimen.

For subgingival application, various antimicrobial agents have been tried, including tetracycline, metronidazole, and chlorhexidine, either on their own or in combination with scaling and root planing (SRP). Chlorhexidine is a highly effective antimicrobial agent that is extensively studied and shown to be effective as a mouthrinse[3] and also as a subgingival irrigant. It shows broad spectrum of topical antimicrobial activity, substantivity, effectiveness, safety, and lack of toxicity.[4]

Chlorhexidine is one of the most effective topical agents, which has long been used as an effective antimicrobial agent.[5] The first sustained release dosage form of chlorhexidine diacetate for topical use was developed by Friedman and Golomb,[6] which had shown effectiveness in reducing the periodontal probing depth, clinical attachment loss, and bleeding on probing.

India has a rich history of using plants for medicinal purposes. Turmeric (haldi), a rhizome of Curcuma longa, is a common antiseptic used in traditional system of Indian medicine. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane), the main yellow bioactive component of turmeric, has been shown to have a wide spectrum of biological actions.[7] Literature reports have shown that curcumin has anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities, suggesting its potential to be used as a subgingival agent.[2,7]

Safety evaluation studies have indicated that both turmeric and curcumin are well tolerated at a very high dose without any toxic effects.[7]

Also, it is more acceptable, inexpensive, and a viable option for common man. Thus, the present investigations evaluated and compared the efficacy of two local drug delivery systems containing 2% whole turmeric gel and 1% chlorhexidine (Hexigel) in patients with chronic periodontitis.

Aim and objective

To evaluate and compare the clinical effects of topical subgingival application of 2% whole turmeric gel and 1% chlorhexidine gel as an adjunct to SRP in patients suffering from chronic periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fifteen patients (12 males and 3 females, aged 21-55 years) suffering from localized or generalized chronic periodontitis[8] were selected from amongst those visiting the outpatient Department of Periodontology and Oral Implantology, National Dental College and Hospital, Derabassi (Punjab).

Subject selection

Inclusion criteria

Patients with a pocket depth of 5-7 mm in at least three non-adjacent sites in different quadrants of the mouth

Systemically healthy patients

Cooperative patients who could be motivated for further oral hygiene instructions

Patients with more than or equal to 20 teeth

Patients who consented to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients on antibiotic therapy from the past 1 month

Pregnant or lactating women

Patients smoking tobacco

Patients giving a history of allergy to chlorhexidine.

Materials

-

2% Whole turmeric gel

Preparation

The gel was prepared in the Department of Pharmacology, National Dental College, Derabassi. The composition of the gel was 2% turmeric extract, 20% (approx.) pluronic polymer, and water q.s. Pluronic polymer was triturated till an emulsion-like consistency was obtained. To this, turmeric extract was added gradually and triturated well. The mixture was then heated and the gel was thereafter procured. The preparation was then refrigerated and delivered into the selected sites.

Gel containing 1% chlorhexidine (Hexigel).

Clinical parameters

The following clinical parameters were recorded:

Plaque scores using Plaque Index (PI; Silness and Loe, 1964)

Gingivitis using Gingival Index (GI; Loe and Silness, 1963)

Probing depth: Measured by UNC-15 probe

Clinical attachment level: Determined by measuring the distance between base of the pocket and the cemento-enamel junction.

Methods

History was recorded for the selected patients. All the clinical parameters were recorded at the baseline which was followed by SRP. In each patient, on the completion of SRP, selected sites with probing depths between 5 and 7 mm were randomly divided into three groups, each in different quadrant:

Group I: Those receiving 2% turmeric gel

Group II: Those receiving 1% chlorhexidine gel (Hexigel)

Group III: SRP alone (control site).

Both the turmeric gel and chlorhexidine gel were delivered into the selected sites in Group I and Group II, respectively, using a syringe with a needle attached to it. Then these sites including the control site (Group III) were covered with periodontal pack (COE Pack). The patients were instructed to continue with the regular oral hygiene measures and were also informed about symptoms like feeling of pressure, pain, or irritation in the area. They were asked to report to the department if any of the above symptoms developed. All the subjects were recalled after 7 days for pack removal and evaluation for any clinical sign of inflammatory response. They were then recalled after 30 days and 45 days of placement of the local drug to record the clinical parameters. Data so collected were put to statistical analysis to draw conclusions.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Intragroup comparisons between different time intervals in various clinical parameters were analyzed by paired t-test. Intergroup comparisons between the three groups were analyzed by Mann–Whitney test.

RESULTS

A total of 45 sites in 15 patients were treated. In each patient, on completion of SRP, three selected sites with probing depths between 5 and 7 mm were randomly divided into three groups, each in different quadrant, as follows: Group I- Those receiving 2% turmeric gel, Group II- Those receiving Hexigel, and Group III: SRP alone (control site).

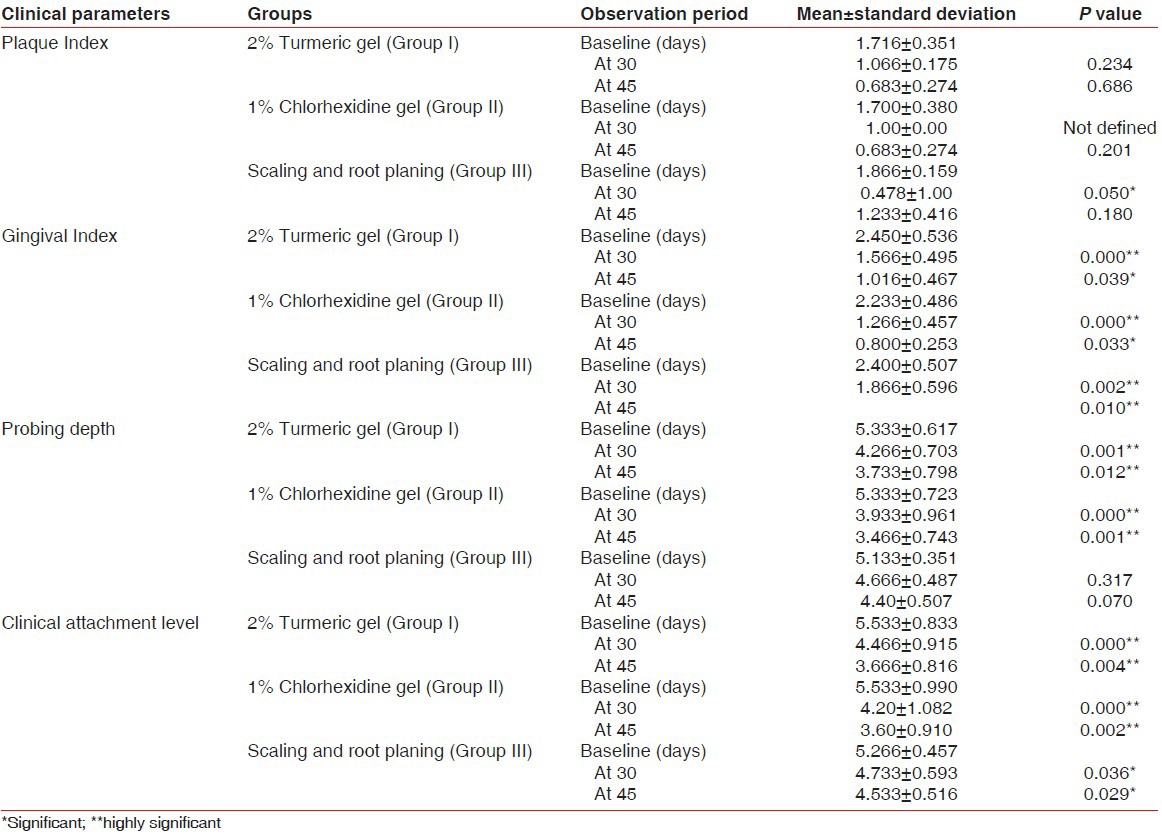

Plaque index

The mean PI scores at baseline, 30 days, and 45 days were observed to be 1.716 ± 0.351, 1.066 ± 0.175, and 0.683 ± 0.274, respectively, for Group I, 1.700 ± 0.380, 1.00 ± 0.00, and 0.683 ± 0.274, respectively, for Group II, and 1.866 ± 0.159, 0.478 ± 1.00, and 1.233 ± 0.416, respectively, for Group III [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of clinical parameters at different time intervals

In Group I, the mean PI scores at 30 days and 45 days from baseline were found to be statistically nonsignificant (P = 0.234 and P = 0.686, respectively). In Group II, a statistically nonsignificant difference was observed in the mean PI scores at 45 days from baseline (P = 0.201). However, this difference from baseline was statistically significant at 30 days (P = 0.050) and nonsignificant at 45 days (P = 0.180) in Group III Table 1.

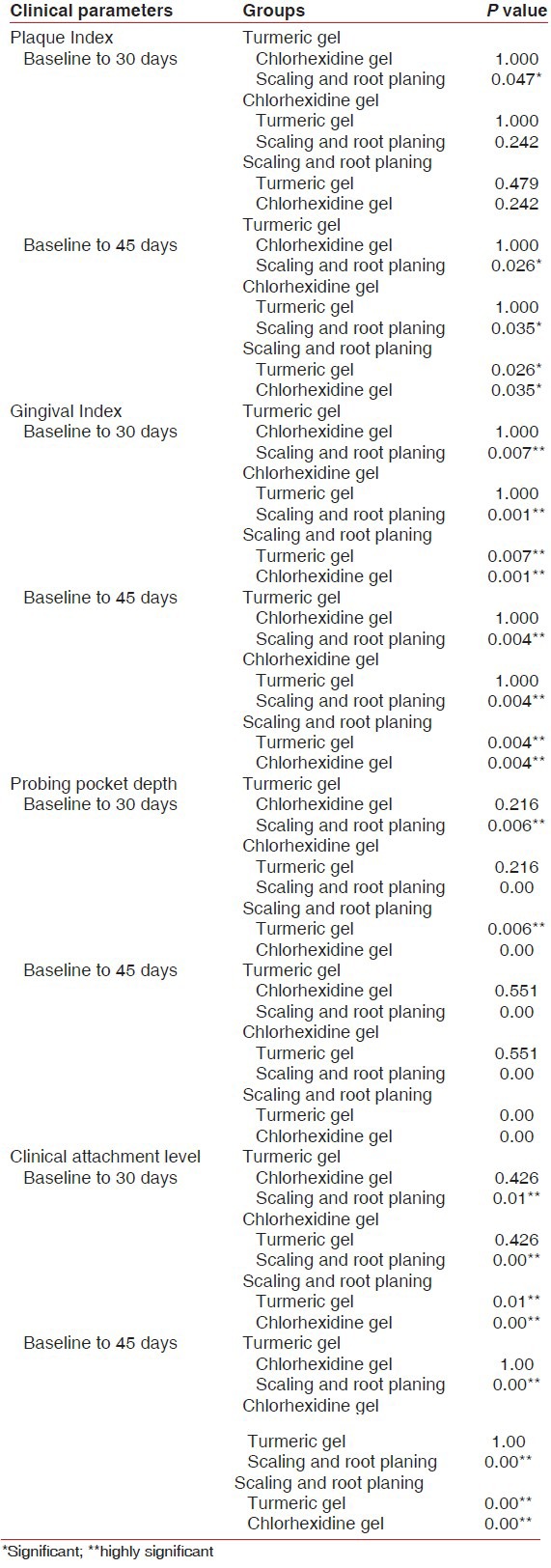

At 45 days from baseline, the mean reduction in PI score was statistically nonsignificant when Groups I and II were compared (P = 1.00). However, this reduction was observed to be statistically significant when Groups I and III (P = 0.026) and Groups II and III were compared (P = 0.035) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Intergroup analysis of clinical parameters at different time intervals

Gingival index

The mean GI scores at baseline, 30 days, and 45 days were observed to be 2.450 ± 0.536, 1.566 ± 0.495, and 1.016 ± 0.467, respectively, for Group I, 2.233 ± 0.486, 1.266 ± 0.457, and 0.800 ± 0.253, respectively, for Group II, and 2.400 ± 0.507, 1.866 ± 0.596, and 1.550 ± 0.613, respectively, for Group III [Table 1].

In Group I, a statistically highly significant difference was found in the mean GI score at 30 days from baseline (P = 0.00) and statistically significant difference was observed from baseline to 45 days (P = 0.039). Similarly, in Group II, the mean GI score at 30 days from baseline was found to be highly significant (P = 0.00) and at 45 days was statistically significant (P = 0.033). However, this difference from baseline was statistically highly significant at 30 days (P = 0.002) and 45 days (P = 0.010) in Group III [Table 1].

At 45 days from baseline, the mean reduction in GI score was statistically nonsignificant when Groups I and II were compared (P = 1.00). However, this reduction was observed to be statistically highly significant when Groups I and II were compared with Group III (P = 0.004) [Table 2].

Probing depth

The mean probing depths at baseline, 30 days, and 45 days were 5.333 ± 0.617, 4.266 ± 0.703, and 3.733 ± 0.798, respectively, for Group I, 5.333 ± 0.723, 3.933 ± 0.961, and 3.466 ± 0.743, respectively, for Group II, and 5.133 ± 0.351, 4.666 ± 0.487, and 4.40 ± 0.507, respectively, for Group III [Table 1].

In Groups I and II, a statistically highly significant difference in the mean probing depth was recorded at 30 days (P = 0.001 and 0.00, respectively) and 45 days (P = 0.012 and 0.001, respectively) from baseline. However, in Group III, a nonsignificant difference at 30 days (P = 0.317) and 45 days (P = 0.070) from baseline was observed [Table 1].

At 45 days from baseline, the mean reduction in probing depth was statistically nonsignificant when Groups I and II were compared (P = 0.055). However, this reduction was observed to be statistically highly significant when Groups I and II were compared with Group III (P = 0.000) [Table 2].

Clinical attachment level

The mean clinical attachment levels at baseline, 30 days, and 45 days were 5.533 ± 0.833, 4.466 ± 0.915, and 3.666 ± 0.816, respectively, for Group I, 5.533 ± 0.990, 4.20 ± 1.082, and 3.60 ± 0.910, respectively, for Group II, and 5.266 ± 0.457, 4.733 ± 0.593, and 4.533 ± 0.516, respectively, for Group III [Table 1].

In Groups I and II, a statistically highly significant difference in the mean clinical attachment level was found at 30 days (P = 0.00 and 0.00, respectively) and 45 days (P = 0.004 and 0.002, respectively) from baseline. However, in Group III, a significant difference at 30 days (P = 0.036) and 45 days (P = 0.029) from baseline was observed [Table 1].

At 45 days, statistically nonsignificant difference in clinical attachment level was observed between Groups I and II (P < 1.00). Statistically highly significant difference was observed when Groups I and II were compared to Group III (P = 0.00) [Table 2].

DISCUSSION

The primary role of bacteria in the etiology of periodontal diseases is unequivocal. Various treatments have been used for it, yet traditional mechanical debridement to disrupt the subgingival flora and provide clean, smooth, and biologically compatible root surfaces is still the mainstay. Even though the outcome of mechanical debridement usually satisfies in terms of reduction in probing depth and bleeding on probing, difficulties reaching the bottom of the pocket can lead to its failure.[9] As a consequence, supplementary treatment becomes inevitable. Moreover, it has also been demonstrated that the time spent on therapy, the number of sites that require instrumentation,[10] and the experience of the clinician may influence the success of SRP.[11] These findings indicate that SRP is a technique-sensitive method for treating periodontitis. Furthermore, some microbiota simply cannot be mechanically eradicated. Indeed, bacterial invasion in cementum, radicular dentin,[12,13] and the surrounding periodontal tissues[14,15,16,17] has been reported. The idea of subgingivally applying a highly concentrated antimicrobial agent as an adjunct to SRP was to compensate for the shortcomings of the former, thereby improving the treatment outcome. Chlorhexidine has long been the gold standard for subgingival chemical plaque control regimens.[4] Its efficacy as a topical rinse to inhibit dental plaque and gingivitis has been well established without evidence of development of any bacterial resistance.[18] It has been found to be effective against subgingival bacteria when delivered through a sustained release device. Chlorhexidine has been shown to be an effective agent in plaque inhibition[19] as it is well retained (substantivity) in the oral cavity. It is safe and is acceptable in terms of cost and ease of use.

However, it has various side effects like brown discoloration of teeth, dulling of taste sensation, and oral mucosal erosion. Therefore, a need was felt for an alternative antimicrobial agent that could provide a product already enmeshed within the traditional Indian setup and is also safe and economical.

Turmeric, more commonly known as “haldi,” possesses anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties along with antimutagenic and anticoagulant activities.[2,7] It also accelerates wound healing.[2] Due to these reasons, it was felt that promotion of turmeric in dental terrain may prove beneficial.

In terms of taste and acceptance of turmeric gel, there was good biological acceptability without any side effects. It was simple and easy to use; also, its bioadhesive property allowed its better retention.

Hence, the aim of the present investigation was to evaluate and compare the clinical effects of topical subgingival application of 2% whole turmeric gel and chlorhexidine gel as an adjunct to SRP in patients suffering from chronic periodontitis.

Patients with a pocket depth of 5-7 mm in at least three non-adjacent sites in different quadrants of the mouth were selected. This was in accordance with Goodson[20] who pointed out that successful control of periodontal microflora in pockets ≥5 mm requires locally delivered antimicrobials reaching the site of action, that is, the periodontal pocket and its surrounding tissues, thus maintaining minimum effective concentrations for sufficient duration to produce a therapeutic effect.

Clinical parameters (PI, GI, probing depth, and relative attachment level) were recorded at baseline, 30 days, and 45 days in all three groups (Group I: 2% turmeric gel, Group II: 1% chlorhexidine gel, and Group III: SRP).

The results of the present investigation show that chlorhexidine gel as the local drug system in Group II was better than SRP alone in Group III. This could be attributed to the substantivity and antimicrobial property imparted by chlorhexidine. This finding is in accordance with the findings of the studies conducted by Unsal et al.[21] and Vinholis et al.[22] who used 1% chlorhexidine gel in the treatment of periodontal pockets.

However, Group I (turmeric gel) showed comparable improvement in all the clinical parameters as Group II (chlorhexidine gel). These results suggest effective usage of turmeric gel as a potential local drug delivery system which could aid in the treatment of periodontal disease. It proved to be a more effective treatment modality than SRP alone, as demonstrated by the clinical parameters. These results are consistent with those reported by Behal et al.[2]

Thus, results of the present study brighten the futuristic aspect of using turmeric gel as a local drug delivery system in subgingival sites. The limitation of the present clinical trial was the small sample size and the short duration for determining the efficacy of the experimental drug. Thus, further longitudinal studies are recommended with larger sample size for the evaluation of the efficacy of this herbal agent in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. The concomitant biochemical and microbial analysis could also help in better interpretation of findings.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of the present study, 2% whole turmeric gel as an adjunct to SRP proved to be effective in the treatment of periodontitis. The bioadhesive property of this local drug delivery system allowed better retention and was biologically accepted without any side effects. Moreover, it was simple to use and required less chairside time. So, it appears as a viable and an inexpensive option for common man and can be incorporated as a treatment modality in day-to-day life.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shifrovitch Y, Binderman I, Bahar H, Berdicevsky I, Zilberman M. Metronidazole-loaded bioabsorbable films as local antibacterial treatment of infected periodontal pockets. J Periodontol. 2009;80:330–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behal R, Mali AM, Gilda SS, Paradkar AR. Evaluation of local drug-delivery system containing 2% whole turmeric gel used as an adjunct to scaling and root planning in chronic periodontitis: A clinical and microbiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:35–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.82264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soskolne WA, Proskin HM, Stabholz A. Probing depth changes following 2 years of periodontal maintenance therapy including adjunctive controlled release of chlorhexidine. J Periodontal. 2003;74:420–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arweiler NB, Boehnke N, Sculean A, Hellwig E, Auschill TM. Difference in efficacy of two commercial 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthrinse solutions: A 4-day plaque re-growth study. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:334–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Divya PV, Nandakumar K. Local drug delivery-periocol in periodontics. Trends Biomater Artif Organs. 2006;19:74–80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinberg D, Friedman M, Soskolne A, Sela MN. A new degradable controlled release device for treatment of periodontal disease: In vitro release study. J Periodontol. 1990;61:393–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.7.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chattopadhyay I, Biswas K, Bandyopadhyay U, Banerjee RK. Turmeric and curcumin: Biological actions and medicinal applications. Curr Sci. 2004;87:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosyn J, Wyn I, De Rouck T, Sabzevar MM. Long-term clinical effects of a chlorhexidine varnish implemented treatment strategy for chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2006;77:406–15. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffiths GS, Smart GJ, Bulman JS, Weiss G, Shrowder J, Newman HN. Comparison of clinical outcomes following treatment of chronic adult periodontitis with subgingival scaling or subgingival scaling plus metronidazole gel. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:910–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027012910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brayer WK, Melloning JT, Dunlap RM, Marinak KW, Carson RE. Scaling and root planing effectiveness: The effect of root surface access and operator experience. J Periodontol. 1989;60:67–72. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adriaens PA, De Boever JA, Loesche WJ. Bacterial invasion in root cementum and radicular dentin of periodontally diseased teeth in humans. A reservoir of periodontopathic bacteria. J Periodontol. 1988;59:222–30. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.4.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adriaens PA, Edwards CA, De Boever JA, Loesche WJ. Ultrastructural observations on bacterial invasion in cementum and radicular dentin of periodontallydiseased human teeth. J Periodontol. 1988;59:493–503. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.8.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allenspach-Petrzilka GE, Guggenheim B. Bacterial invasion of the periodontium; an important factor in the pathogenesis of periodontitis? J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:609–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saglie R, Newman MG, Carranza FA, Jr, Pattison GL. Bacterial invasion of gingiva in advanced periodontitis in humans. J Periodontol. 1982;53:217–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.4.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sreenivasan PK, Meyer DH, Fives-Taylor PM. Requirements for invasion of epithelial cells by Actinobacillusactinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1239–45. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1239-1245.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winkler JR, Matarese V, Hoover CI, Kramer RH, Murray PA. An in vitro model to study bacterial invasion of periodontal tissues. J Periodontol. 1988;59:40–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiott CR, Briner WW, Loe H. Two year oral use of chlorhexidine in man. II. The effect on the salivary bacterial flora. J Periodontal Res. 1976;11:145–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1976.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loe H, Schiott CR, Karring G, Karring T. Two years oral use of chlorhexidine in man. I. General design and clinical effects. J Periodontal Res. 1976;17:135–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1976.tb00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodson JM. Phamacokinetic principles controlling efficacy of oral therapy. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1625–32. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unsal E, Akkaya M, Walsh TF. Influence of a single application of subgingival chlorhexidine gel or tetracycline paste on the clinical parameters of adult periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:351–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinholis AH, de Figueiredo LC, Marcantonio E, Junior, Marcantonio RA, Salvador SL, Goissis G. Subgingival utilization of 1% chlorhexidine gel for treatment of periodontal pockets. A clinical and microbiological study. Braz Dent J. 2001;12:209–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]