Abstract

Aim:

The present study was undertaken to evaluate patient response and recurrence of pigmentation following gingival depigmentation carried out with a surgical blade and diode laser.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty patients who were esthetically conscious of their dark gums and requested treatment for the same were selected for this study. Complete phase I therapy was performed for all the patients before performing the gingival depigmentation procedures with laser and scalpel on a split-mouth basis. Patients were evaluated for pain (1 day, 1 week), wound healing and melanin repigmentation (Melanin Pigmentation Index) immediately and at 1 week, 1 month and 3 months, respectively.

Results:

The final results were statistically analyzed and significance was evaluated. The results of this study indicated that both scalpel and laser were efficient for gingival depigmentation. Comparative pain assessment (P = 0.148) and repigmentation scores (P = 0.288) at various time intervals between the two groups did not show any statistical significance.

Conclusion:

Both the procedures did not result in any post-operative complications and the gingiva healed uneventfully. When compared, both the techniques were found to be equally efficacious. Care must be taken to assess the gingival biotype and the degree of pigmentation in deciding which technique is to be used.

Clinical Significance:

Various methods of depigmentation are available with comparable efficacies. Depigmentation is not a clinical indication but a treatment of choice where esthetics is a concern and is desired by the patient.

Keywords: Diode lasers, gingiva, melanin pigmentation, pathologic, physiologic, scalpel surgery

INTRODUCTION

The harmony of smile is determined not only by the shape, the position and the color of the teeth but also by the gingival tissue.[1] Gingival health and appearance are essential components for an attractive smile, and removal of unsightly pigmented gingiva is the need for a pleasant and confident smile.[2] Melanin, a brown pigment, is the most common natural pigment contributing to endogenous pigmentation of the gingiva. It is a non–hemoglobin-derived pigment formed by cells called melonocytes that are dentritic cells of neuroectodermal origin in the basal and spinous layers.[3]

Oral pigmentation occurs in all races of man. There are no significant differences in oral pigmentation between males and females. The intensity and distribution of racial pigmentation of the oral mucosa is variable, not only between races but also between different individuals of the same race and within different areas of the same mouth. Physiologic pigmentation is probably genetically determined, but, as suggested by Dummett (1946),[4] the degree of pigmentation is partially related to mechanical, chemical and physical stimulation. In darker skinned people, oral pigmentation increases but there is no difference in the number of melanocytes between fair-skinned and dark-skinned individuals. The variation is related to differences in the activity of melanocytes. There has been controversy about the relationship between age and oral pigmentation. Steigmann and Shulamit (1965) stated that all kinds of oral pigmentation appear in young children.[5] Prinz (1932), on the other hand, claimed that physiologic pigmentation did not appear in children and was clinically visible only after puberty.[6]

Demand for cosmetic therapy of gingival hyperpigmentation is common. Various methods such as chemicals, gingivectomy, gingivectomy with free gingival autografting, acellular dermal matrix allografts, electrosurgery, cryosurgery, abrasion with diamond bur and various types of lasers have been used in the treatment of gingival melanin depigmentation with varied degrees of success.[7]

The first and foremost indication for depigmentation is patient demand for improved esthetics. The selection of technique should be based on clinical experience and individual preferences.[3] The present study was aimed to evaluate and compare the patient response and the duration of reappearance of gingival pigmentation following laser and scalpel gingival depigmentation techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sample

Twenty patients, 11 male and nine female, within an age range of 15-35 years reporting for the treatment of gingival melanin hyperpigmentation were selected from the outpatient Department of Periodontology, SGT Dental College, Hospital and Research Institute, Gurgaon. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee on Human Research of Pandit B D Sharma University of Health Sciences, Rohtak. (Patients were briefed about the surgical procedure and informed consent was taken. The patients included in the study were aged at least 15 years, had moderate to severe physiologic gingival melanin hyperpigmenation (as given by Dummett Gupta in 1964),[8] with well-maintained oral hygiene, with esthetic concern, systemically healthy and those willing to undergo minor surgical procedures [Figure 1]).

Figure 1.

Pre-operative

The patients excluded from the study were with any systemic disease associated with pathological hyperpigmentation or improper delayed wound healing (uncontrolled diabetes, autoimmune diseases, etc.), with non-treated periodontal disease, chronic smokers and non-compliant patients.

Method

Appropriate medical and dental history concerning the absolute and relative contraindications were procured for further evaluation of the subject.

The procedure was carried out in the maxillary anterior sextant (divided into two segments) -

Segment 1: Right anterior segment (Scalpel procedure) [Figure 2]

Figure 2.

Segment 1 - Scalpel side with blade

Segment 2: Left anterior segment (Laser procedure).

Scalpel procedure

Local anesthesia was obtained with infiltration (2% Lidocaine with Adrenaline 1:2,00,000) in relation to the surgical site (for segment 1). The gingival epithelium was excised with Bard Parker blade number 15 and 11 [Figures 3 and 4]. The excision involved the entire pigmented area extending from the free gingival margin to the mucogingival junction from the mid line extending up to the first premolar, with the blade placed almost parallel to the long axis of the teeth with care taken not to expose the underlying bone. The entire epithelium was removed in one piece. Orban's knife was used to remove the residual epithelium in the interdental areas. This was followed by careful examination of the exposed connective tissue surface and any remaining tissue tags were removed by surgical scissors. Bleeding was controlled using a pressure pack and, once hemostasis was achieved, the site was covered by periodontal dressing for a period of 1 week.[9]

Figure 3.

Segment 1 - Scalpel side procedure complete

Figure 4.

Segment 1 - Slice of pigmented tissue removed

Laser Procedure (FONA Diode Laser™, Sirona Germany)

The procedure was started with the application of topical anesthesia (Lidocaine Topical Aerosol - LOX™ 10% spray) in segment 2. The fiberoptic laser tip having a 320 μm diameter at 2.5 W power was kept in contact with the pigmented area and laser was emitted in a gated pulsed mode [Figures 5 and 6] and operated between the wavelengths of 800 and 980 nm. Depigmentation was performed with short light paint brush strokes in a horizontal direction to remove the epithelial lining. The area to be depigmented was wiped with gauze soaked in saline solution and the same procedure was repeated till no pigments remained. Following the procedure, no periodontal pack was given and no antibiotics were administered.[10]

Figure 5.

Segment 2 - Laser tip placed

Figure 6.

Segment 2 - Laser side procedure complete

The post-surgical evaluation protocol was conducted by a second examiner (YS) for assessing wound healing, Melanin Pigmentation Index and pain perception using Visual Analog Scale (VAS) at the following time intervals.

Immediately after surgery

Patients were evaluated immediately after surgery for healing of wound and Melanin Pigmentation Index [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Immediate post-op - COE PAKTM periodontal dressing placed on Segment 1 (scalpel side)

One day after surgery

Patients were evaluated for pain using the VAS [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

One day post-operative

One week after surgery

Patients were evaluated after 1 week of surgery for healing of wound, Melanin Pigmentation Index and VAS [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

1 week post-operative

One month after surgery

Patients were evaluated after 1 month of surgery for healing of wound, Melanin Pigmentation Index and VAS [Figure 10].

Figure 10.

One month post-operative

Three months after surgery

Patients were evaluated after 3 months of surgery for healing of wound, Melanin Pigmentation Index and VAS [Figure 11].

Figure 11.

Three months post-operative

Wound healing was evaluated as per the list of clinical observations and patient responses prepared by Sharon et al. (2000)[11] and Tal et al. (2003).[12] Each parameter was evaluated as:

Complete epithelization

Incomplete epithelization

Ulcer

Tissue defect or necrosis.

The VAS was used to evaluate the subjective pain level experienced by each patient. It consists of a horizontal line 100 mm (10 cm) long, starting at the left end with the descriptor “no pain” and ending at the right end with “unbearable pain.” Patients were asked to mark the severity of their pain. The distance of this point, in millimeters, from the left end of the scale was recorded and used as the VAS score). Score 0 was recorded as no pain, scores between 1 and 30 were recorded as slight pain, scores between 31 and 60 were considered as moderate pain and scores of 61-100 were recorded as severe pain.[13]

Pre-operative and 3 months’ post-operative comparisons are shown in Figures 1 and 11, respectively.

The data obtained were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 19, for Windows OS. Mean and standard deviations were calculated for the clinical parameter (pain). Student's t-test was employed to determine the difference between the mean values of pain between the two groups. The Chi square test was employed to determine the difference between wound healing and melanin pigmentation.

RESULTS

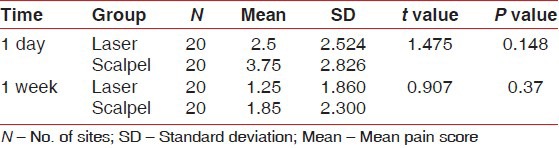

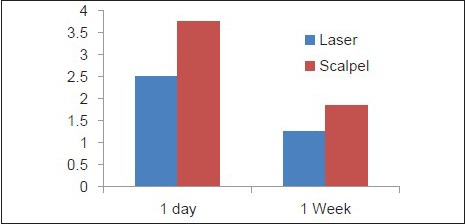

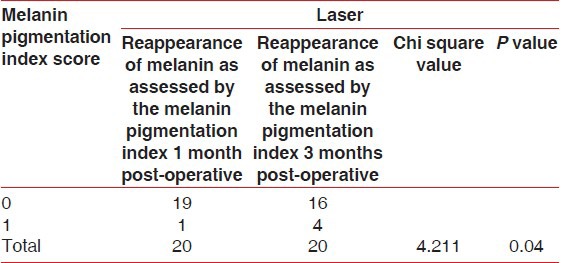

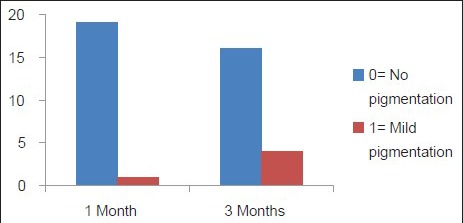

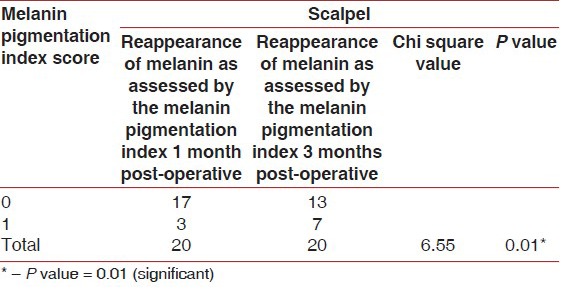

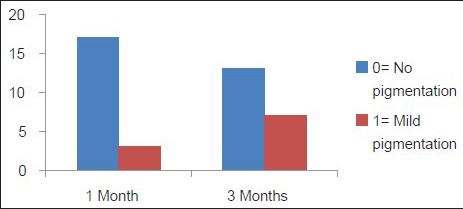

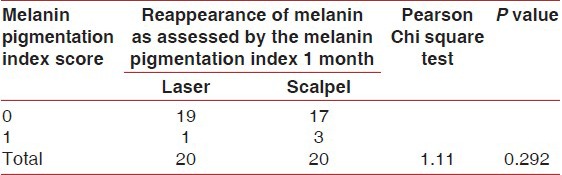

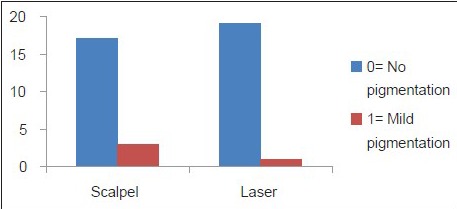

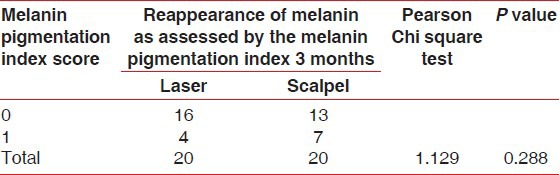

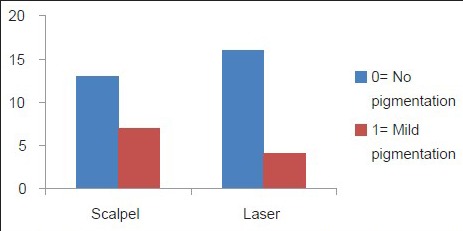

The final results were statistically analyzed and significance evaluated. Difference in pain was assessed using VAS scores in both the groups after 1 day and 1 week. No statistically significant difference was found between the groups (P value = 0.148, 0.37) [Table 1 and Graph 1]. On comparison in the laser group, a statistically significant difference was found between melanin repigmentation between 1 month and 3 months (P value = 0.04) [Table 2 and Graph 2]. On comparison in the scalpel group, a statistically significant difference was found between melanin repigmentation between 1 month and 3 months (P value = 0.01) [Table 3 and Graph 3]. On comparison of melanin reappearance at 1 month, between the scalpel and the laser groups, no statistically significant difference was found (P = 0.292) [Table 4 and Graph 4]. On comparison of melanin reappearance at 3 months, between the scalpel and the laser groups, no statistically significant difference was found (P = 0.288) [Table 5 and Graph 5]. Results of other parameters could not be evaluated statistically because one of the parameters was constant in either group.

Table 1.

Difference in pain after 1 day and 1 week in individuals treated with laser and scalpel

Graph 1.

Difference in pain after 1 day and 1 week in individuals treated with laser and scalpel

Table 2.

Difference in melanin reappearance in the laser group at 1 month and 3 months

Graph 2.

Difference in melanin reappearance in the laser group at 1 month and 3 months

Table 3.

Difference in melanin repigmentation between 1 month and 3 months

Graph 3.

Difference in melanin repigmentation between 1 month and 3 months

Table 4.

Difference in melanin reappearance after 1 month in individuals treated with laser and scalpel

Graph 4.

Difference in melanin reappearance after 1 month in individuals treated with laser and scalpel

Table 5.

Difference in melanin reappearance after 3 months in individuals treated with laser and scalpel

Graph 5.

Difference in melanin reappearance after 3 months in individuals treated with laser and scalpel

DISCUSSION

Oral pigmentation occurs in all races of man, and the gingiva is the most frequently pigmented intraoral site (Dummett and Gupta 1964).[8] This pigmentation may be seen across all races and at any age, and it is without a gender predilection. Melanin pigmentation of the gingiva is completely benign and does not present a medical problem. Complaints of “black gums” are common and a demand for depigmentation is usually made for esthetic reasons.[14] Many techniques have been tried in the past to treat gingival pigmentation, which include chemical cauterization, gingivectomy, abrasion of the gingiva, cryotherapy, free gingival autograft and laser therapy.[7]

Gingival depigmentation performed in this study with a blade was precise, definite and under control. With this technique, it was possible to appreciate the depigmented areas immediately and did not leave room for any residual pigments. However, this technique required the use of local anesthesia, resulted in hemorrhage and required immense care while excising the epithelium in order not to expose the bone or to create gingival recession. It was necessary to cover the surgical site with periodontal dressing for 7-10 days to protect the site from food debris, foreign irritants, thermal stimuli and infection. Comparatively, the use of the scalpel technique for depigmentation is the most economical as compared with other techniques that require more advanced armamentarium.[15]

Recently, laser ablation has been recognized as one of the most effective, comfortable and reliable techniques for gingival depigmentation.[16] The word laser is an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation. Maiman (1960) developed the first working laser. The first application of a laser to dental hard tissue was reported by Goldman et al. (1964)[17] and Stern and Sognnaes (1972)[18] described the effects of the ruby laser on enamel and dentin.

The diode laser of 800 - 980 nm and 8 W (Sirona Diode System™, Germany) was used in this study as it has a near-optimal absorption in melanin and hemoglobin.[19] The procedure was started with the application of topical anesthesia (Lidocaine Topical Aerosol - LOX™ 10% spray) in segment 2 and the fiberoptic laser tip having 320 μm diameter at 2.5 W power kept in contact with the pigmented area and laser was emitted in gated pulsed mode and operated between the wavelengths of 800 and 980 nm to the adjacent and underlying tissues. Higher power (>2.5 W) would manifest as discomfort and pain during the post-operative period and, moreover, could delay the healing time. Therefore, as a rule, a low-power setting (≤2.5) was used during the procedure.[20]

Laser was used in the gated pulsed mode. Taking into account the undue heating that could be caused to the surrounding normal and pink tissues where the melanin pigmentation was absent, a gated pulsed mode provided the necessary thermal relaxation as against using a continuous pulse mode.[20]

The post-operative experience of pain is a complex phenomenon, influenced by psychological, environmental and physical factors. VAS is a reliable method to assess pain in clinical settings when compared with the verbal rating scale. VAS scores are sensitive to treatment effects and the data derived can be analyzed using parametric statistical techniques.[15] The pain perception was less in the laser group as protein coagulum is formed on the wound surface, which serves as a biological wound dressing and seals the ends of the sensory nerves.[15]

There was no significant correlation seen between the pain levels and gender.

The present study did not show any significant difference in healing of depigmented areas of the gingiva, although mild pain and inflammatory changes were seen in the surgical excision area but were statistically not significant.

In both the procedures, evaluation on 30 days revealed restoration of normal features of the gingiva without any scar formation. Thus, the healing of the depigmented gingiva was uneventful irrespective of the techniques used.

Melanin is produced by specialized pigment cells in the gingiva called melanocytes. They are located primarily in the basal layer of the epithelium. Hence, it is necessary to remove the entire epithelium. The wound healing takes place by proliferation of cells present along the periphery of the wound. These cells migrate and help in reepithelialization of the wound. Thus, oral repigmentation refers to the clinical reappearance of melanin pigment after a period of clinical depigmentation of the oral mucosa.[2]

In 11 cases, four laser and seven scalpel, a patchy repigmentation was observed at the end of 3 months, which could be a result of the ongoing process of repigmentation. The decreased intensity of pigmentation may be due to the lesser production of pigments. The intensity may increase with time and may reach to pre-treatment level as it depends on the racial background of the patient. The results are consistent with the finding of Bergamaschi et al., who demonstrated that permanent results cannot be offered when gingival depigmentation procedures are performed for cosmetic reasons.[21]

Also, Perlmutter and Tal[22] reported the case of one patient in whom gingival repigmentation occurred 7 years after removal of gingival tissues. Dummet and Bolden (1963)[23] observed partial recurrence of hyperpigmentation in six out of eight patients after gingivectomy at 1-4 months.

Nakamura et al.[24] described depigmentation with CO2 laser in 10 patients. No repigmentation was seen in the 1st year, but four patients showed repigmentation by 24 months. The recurrence of pigmentation can be due to the nature of the melanocytes. These cells arise from the neural crest ectoderm and enter the epithelium as melanocytes from about the 8th gestational week and, by the 14th week, these cells may have reached densities of 2000/mm2 in some regions.

Melanocytes have a reproductive self-maintaining system of cells. When locally depleted, they repopulate and keratinocyte-derived growth factors Fibroblast Growth Factor-β act as a mitogen. These cells lack desmosomes and possess long dendritic processes that extend between keratinocytes. Melanin is synthesized in the melanocytes in small structures called melanosomes. These melanosomes are injected into the keratinocytes by the dendritic processes. All individuals, whether lightly or darkly pigmented, have the same number of melanocytes in any given region of the mucosa. But, it has been observed that cells with melanin are present in connective tissue in the case of individuals who have a very high melanin pigment. These cells are actually macrophages that have engulfed the melanin pigment.[23]

In case of surgical excision, there was repigmentation in four patients at the end of 30 days, and seven of 20 patients had developed specks of repigmentation at the end of 90 days post-operative. The remaining 13 patients did not develop any repigmentation until the entire study period. In case of laser, there was repigmentation in one patient at the end of 30 days, and four of 20 patients had developed specks of repigmentation at the end of 90 days post-operative. The remaining 16 patients did not develop any repigmentation until the entire study period. In earlier studies by Ginwalla,[25] Dummett[23] and Pal,[26] occurrence of repigmentation following 24, 33 and 15 days, respectively, has been reported.

The mechanism of repigmentation is not understood, but according to the migration theory, active melanocytes from the adjacent pigmented tissues migrate to the treated areas, causing failure. Reports of repigmentation are quite limited and varied. Studies by Ginwalla et al.[25] showed repigmentation of 50% of the cases by using the abrasion technique after 24 -56 days.[13] Pal et al.[26] showed that repigmentation occurred in 19% of the cases following gingival depigmentation by surgical bur.

The laser procedure was more acceptable to the patient as the procedure took less time and was more comfortable as the area did not require injecting local anesthesia and absence of post-operative pain and hemorrhage. Also, from the operator's point of view, the laser technique was easier and faster to perform than the epithelial excision technique. Ribeiro et al.[27] and Simşek Kaya et al.[20] found similar results: That the subjects experienced a higher extent of discomfort/pain on the side treated by the scalpel technique as compared with the diode laser-treated side during the first post-therapy week. Also, the use of a diode laser presented advantages in terms of less discomfort/pain during the post-therapy period and a reduction of treatment chair time.

The success of the depigmentation procedure may be weighed only by the extent of depigmentation achieved and by the time taken for reappearance of pigments, prolonged follow-up is necessary. As the post-operative follow-up of the present study was short, it is proposed that further studies be taken up for a longer period of monitoring along with histopathological assessment to understand the process of repigmentation.

CONCLUSION

As per this study, no statistical significance was seen in the comparison of both techniques in terms of efficiency and repigmentation. The results of this study indicated that both scalpel as well as laser were efficient for depigmentation of the gingiva. Both the procedures did not result in any post-operative complication and the gingiva healed uneventfully. Choice of technique to be used mainly depends on the gingival biotype and the degree of pigmentation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deepak P, Sunil S, Mishra R, Sheshadri Treatment of gingival pigmentation: A case series. Indian J Dent Res. 2005;16:171–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doshi Y, Khandge N, Byakod G, Patil P. Management of gingival pigmentation with diode laser: Is it a predictive tool? Int J Laser Dent. 2012;2:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thangavelu A, Elavarasu S, Jayapalan P. Pink esthetics in periodontics-gingival depigmentation: A case series. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2012;4(Suppl 2):186–90. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.100267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dummett CO. Physiologic pigmentation of the oral and cutaneous tissues in the negro. J Dent Res. 1946;25:421–32. doi: 10.1177/00220345460250060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steigmann S. The relationship between physiologic pigmentation of the skin and oral mucosa in Yemenite jews. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;19:32–8. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermann P. Pigmentations of the oral mucous membranes The The Dental Cosmos is only name available and can be verified from this link: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/d/dencos/0527912.0074.001/608:446rgn?=full+text; view=image . 1932;74:554–61. Available from: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/d/dencos/0527912.0074.001/608:446?rgn=full+text;view=image . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roshna T, Nandkumar K. Anterior esthe. tic gingival depigmentation and crown lenthening: Report of a case. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cicek Y, Ertas U. The normal and pathological pigmentation of oral mucous membrane: A review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2003;4:76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humagain M, Nayak DG, Uppoor AS. Gingival depigmentation: A case report with review of literature. J Nepal Dent Assoc. 2009;10:53–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozbayrak S, Dumlu A, Ercalik-Yalcinkaya S. Treatment of melanin-pigmented gingiva and oral mucosa with CO2 laser. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:14–5. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.106396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharon E, Azaz B, Ulmansky M. Vaporization of melanin in oral tissues and skin with carbon dioxide laser: A canine study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:1387–94. doi: 10.1053/joms.2000.18272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tal H, Oegiesser D, Tal M. Gingival depigmentation by erbium: YAG laser: Clinical observations and patient responses. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1660–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.11.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagdive S, Doshi Y, Marawar PP. Management of gingival hyperpigmentation using surgical blade and diode laser therapy: A comparative study. J Oral Laser Applications. 2009;9:41–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dummett CO, Gupta OP. Estimating the epidemiology of oral pigmentation. J Natl Med Assoc. 1964;56:419–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaarthikeyan G, Jayakumar ND, Padmalatha O, Varghese S, Kapoor R. Pain assessment using a visual analog scale in patients undergoing gingival depigmentation by scalpel and 970 nm diode laser surgery. J Laser Dent. 2012;20:20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berk G, Attici K, Berk N. Treatment of gingival pigmentation with Er, Cr: YSGG laser. J Oral Laser Applications. 2005;5:249–53. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldman L, Hornby P, Meyer R, Goldman B. Impact of the laser on dental caries. Nature. 1964;203:417. doi: 10.1038/203417a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stern RH, Sognnaes RF. Laser inhibition of dental caries suggested by first tests in vivo. J Am Dent Assoc. 1972;85:1087–90. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1972.0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Academy of Laser Dentistry. Featured wavelength: Diode-the diode laser in dentistry (Academy report) Wavelengths. 2000;8:13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simşek Kaya G, Yapici Yavuz G, Sümbüllü MA, Dayi E. A comparison of diode laser and Er: YAG lasers in the treatment of gingival melanin pigmentation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:293–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergamaschi O, Kon S, Doine AI, Ruben MP. Melanin repigmentation after gingivectomy: A 5-year clinical and transmission electron microscopic study in humans. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1993;13:85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perlmutter S, Tal H. Repigmentation of the gingiva following surgical injury. J Periodontol. 1986;57:48–50. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dumett CO, Bolden TE. Post surgical clinical repigmentation of the gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1963;16:353–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura Y, Hossain M, Hirayama K, Matsumoto K. A clinical study on the removal of gingival melanin pigmentation with the CO (2) laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1999;25:140–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1999)25:2<140::aid-lsm7>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ginwalla TM, Gomes BC, Varma BR. Surgical removal of gingival pigmentation. J Indian Dent AssocJournal of Indian Dental Association. 1966;38:147–50. passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pal TK, Kapoor KK, Parel CC, Mukharjee K. Gingival melanin pigmentation: A study on its removal for esthetics. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 1994;3:52–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribeiro FV, Cavaller CP, Casarin RC, Casati MZ, Cirano FR, Dutra-Corrêa M, et al. Esthetic treatment of gingival hyperpigmentation with Nd: YAG laser or scalpel technique: A 6-month RCT of patient and professional assessment. Lasers Med Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10103-012-1254-5. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]