Abstract

Background:

The current cross-sectional questionnaire survey was conducted to assess the oral health-related knowledge, attitude and practices among eunuchs (hijras) residing in Bhopal city, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Materials and Methods:

Based on a convenient non-probability snow ball sampling technique, all the self-identified eunuchs residing in the city of Bhopal who were present at the time of study and who fulfilled the selection criteria were approached. A cross section of the general population was also surveyed. An interviewer-based, predesigned, structured, close-ended 18-item questionnaire that had been designed based on the primary objective of the study was used. All the obtained data were analyzed using software, Statistical Package for Social Science version 20.

Results:

According to 188 (86.2%) males, 187 (87.4%) females and 168 (81.2%) eunuchs, good oral health can improve the general health. Most of the study participants including 211 (98.6%) females, 210 (96.3%) males and 205 (99%) eunuchs use either tooth paste or tooth powder to clean their teeth. While, a majority of eunuchs, i.e., 113 (54.6%), were having habit of chewing smokeless tobacco containing products such as betel nut, betel quid, gutkha, etc., The difference in use of tobacco products was statistically significant.

Conclusion:

The information presented in this study adds to our understanding of the common oral hygiene practices which are performed among eunuch population. Efforts to increase the awareness of oral effects of tobacco use and to eliminate the habit are needed to improve oral and general health of this population.

Keywords: Eunuchs, hijras, oral health, oral hygiene practices, periodontitis

INTRODUCTION

Prevalence and severity of periodontal diseases vary from individual to individual and are affected by age, gender, education and socioeconomic status. Most of the chronic periodontal pathologies are directly related to lifestyle and are considered as a major public health problem due to its high prevalence and significant social impact.[1] Chronic periodontitis typically leads to tooth loss, and in some cases has physical, emotional and economic impacts: Physical appearance and diet are often worsened, and the patterns of daily life and social relations are often negatively affected.[2] These impacts lead in turn to reduced welfare and quality of life.[1]

Most of the periodontal conditions are plaque induced and are often can be reversed if improved oral hygiene measures are introduced. Hence, to minimize the negative impacts of periodontal diseases, there is thus a clear need to reduce harmful oral hygiene habits. Such a reduction can be achieved through appropriate health education programs.[1,2] The KAP (knowledge, attitude and practice) model of behavioral changes is solidly embedded within the traditional focus of health education. It is a model with a positive vision of science, treating the behavioral change as a logical individual decision.[1]

Knowledge is the ‘expertise and skills acquired by a person through experience or education’.[3] Knowledge acquisition involves complex cognitive processes: Perception, learning, communication, association and reasoning.[3] The term knowledge is used to mean the confident understanding (theoretical or practical) of a subject with the ability to use it for a specific purpose.[4] An attitude is a relatively enduring organization of beliefs around an object, subject or concept which pre-disposes one to respond in some preferential manner.[4,5] Attitude is considered as an acquired characteristic of an individual. Attitude naturally reflects people's own experiences, cultural perceptions, familial beliefs, and other life situations and they strongly influence the oral health behavior.[6] Health behavior as defined by Steptoe and colleagues is ‘the activities undertaken by people in order to protect, promote or maintain health and to prevent disease’.[7] The broad categories of factors that may influence health behavior include: Knowledge, beliefs, values, attitudes, skills, finance, materials, time and the influence of family members, friends, co-workers, opinion leaders and even health workers themselves.[8]

The affected population needs to receive information on periodontal diseases, risk factors and measures that can be adopted to prevent them. Such campaigns will typically aim not only to impart knowledge, but also to improve attitudes regarding oral health, and to facilitate the transformation of these attitudes into practice.[9]

People who are disadvantaged by socioeconomic status experience greater levels of periodontal diseases than those from more affluent groups.[10] Socioeconomically disadvantaged groups rate their oral health poorer than more advantaged groups.[11] In India, there are multiple socioeconomic disadvantages that members of particular group experience which limits their access to health and healthcare.[10] Eunuchs are one of these neglected special vulnerable groups in India, where special attention is required to improve the periodontal and ultimately the overall oral health scenario of the country.

The word EUNUCH is derived from a Greek word meaning “keeper of the bed.”[12] These transgender communities historically exist in many cultural contexts, known as bakla in the Philippines, xaniths in Oman, serrers among the Pokot people of Kenya, and kinnars, jogappas, jogtas, or shiv-shaktis in South Asia.[12]

In India, eunuchs are also called as ‘Hijra’, which actually refers to third gender or ‘male-to-female’ transgender people, most see themselves as neither men nor women.[13] According to Telegraph report, India has an estimated 1.5 million eunuchs.[14] But the census data on them does not exist, so to make an accurate enumeration is impossible as they continue to persist as a marginalized and secretive community.[13] Many hijra come from other sexually ambiguous backgrounds: They may be born inter-sexed, be born male or female and fail to develop fully at puberty, or be males who choose to live as hijra without ever undergoing the castration procedure.[12] They generally live together by forming a group called as ‘Gharana’ (familial house to which they owe allegiance), which is headed by a Guru (most senior member) and other members are as ‘Chelas’ (followers).[13] Their sources of livelihood mainly include performing at marriage and birth celebrations, badhai (ritual performing) basti/mangti (begging) for alms and prostitution.[15]

Unlike in other parts of the world, the attitude toward a hijra in Indian society is discriminatory and biased in general. The hijra claim that mainstream society does not understand their culture, gender, and sexuality. They are considered as the most vulnerable, frustrated, and insecure community of the country.[12] They are also denied general, oral health and psychological assistance.[10] In India, the accessibility to medical and dental facilities for the eunuchs is nearly non-existent. There is every possible chance that this neglected special group of population may have heavy stress and indulge in alcoholism, gutkha-pan chewing and other pernicious habits. These factors may cause many oral health problems especially those related to periodontal health, which can make their lives worse.

The complete absence of published literature on oral health-related aspects of this special group has prompted us to take up the present study to explore the oral hygiene-related knowledge, attitude and practices of Eunuchs (Hijras) residing in the Bhopal city, Madhya Pradesh, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and settings

A cross-sectional questionnaire survey was conducted among the eunuchs of Bhopal city, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Source of data

The study subjects consisted of all the self-identified eunuchs residing in Bhopal city and the matched general population residing in the same locality where these eunuchs live.

Sampling design and sample selection

Based on the convenient non-probability snow ball sampling technique, all the self-identified eunuchs residing in the city of Bhopal who were present at the time of study and who fulfilled the selection criteria were included. Based on interviews with local informants, four prominent localities of the city where most of the eunuchs reside were identified. All the identified areas were visited and eunuchs residing in these areas were contacted. The eunuchs who consented to become part of the study guided us to the similar samples they knew about. The subjects were explored till saturation occurs and no new cases were identified.

A cross section of the general population (males and females) residing in the same locality where these eunuchs live was also included. All the eligible males and females were matched with eunuchs for pertinent variables like age, socioeconomic status and geographical distribution.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Eunuchs: All the self-identified eunuchs available during the study period were considered for the study

The matched controls with the eunuchs for certain pertinent variables like age, socioeconomic status and geographical distribution

Participants who gave informed consent to participate at the time of study.

Exclusion criteria

Participants with history of medication for any systemic illness (medically compromised patients)

Participants not willing to participate in the study

Participants affected with mental retardation, physically and mentally handicapped, orthopedic defects, etc.

Information about study areas

Based on interviews with local informants, four prominent localities of the city where most of the eunuchs reside were identified. The list of identified areas is as follows:

Mangalwara: Ward number-18, Bhopal. (Pre-determined Area code 11)

Budhwara: Ward number-21, Bhopal. (Pre-determined Area code 12)

Patra: Ward number-34, Bhopal. (Pre-determined Area code 13)

Ahamadpurkala: Ward number-53, Bhopal. (Pre-determined Area code 14).

Sample size

A total of 639 subjects including 207 eunuchs, 218 males and 214 females participated in the study.

Ethical clearance

The detailed proposed study protocol was submitted and approved by the ethical committee of Peoples University, Bhopal.

Informed consent

A brief study protocol was explained and written informed consent was obtained from each study subject.

Schedule of the survey

A survey was systematically scheduled to cover all the identified areas of the Bhopal city. The survey period extended for a period of 3 months from April to June 2013.

Pilot study

A preliminary pilot testing of questionnaire was done on 26 Eunuch subjects. The purpose behind this was to know the practical and communication difficulties while surveying this group of subjects.

Method of collection of Data

Assessment and structure of a questionnaire

To assess the oral health-related knowledge, attitude and practice of study subjects an interviewer based, predesigned, structured, close-ended 18 item questionnaire, which had been designed based on the primary objective of the study was used. The interview was conducted in regional language (Hindi). The questionnaire was initially prepared in English, translated into Hindi language and the re-translated back to English to check for consistency. Test retest reliability of questionnaire at the interval of 2 days yielded Intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.90.

The details of the questionnaire are as follows:

Oral health knowledge: The assessment of participant's oral health knowledge included 5 questions (items) on importance of oral health, cause of tooth decay, identification of tooth decay, cause of cancer, dental facilities available in the area

Oral health attitude: 5 questions (items) on attitude toward condition of mouth, regular dental visits, reason of visit and preferred treatment for deeply decayed teeth

Oral health practice: The assessment of participant's oral health behavior included 8 questions (items) on brushing habits, frequency of sugar consumption, tobacco-related habits.

The subjects were asked to respond to each item according to the response format provided in the questionnaire. Response format included multiple choice questions in which the subjects were asked to choose an appropriate response from provided list of options. The investigator recorded the responses of the subjects in the printed format. The completed response format was carefully checked by the investigator. Along with the questionnaire, information on demographic characteristics like age, sex, occupation, educational level, and socioeconomic status was also collected.

Statistical analysis

All the obtained data was entered into a personal computer on Microsoft excel sheet and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, IBM, USA) version 20. The statistically significant level was set at less than 0.05 with confidence interval of 95%. The Chi-square test was used to compare the proportions.

RESULTS

The population under study (eunuchs) consisted mainly of individuals living in isolated settlements away from the general population. A total of 639 subjects were examined. Of these 218 (34.1%) were males, 214 (33.5%) were females and 207 (32.4%) were eunuchs.

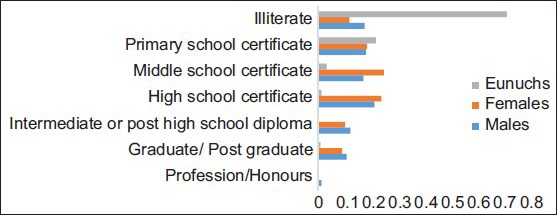

Figure 1 shows the distribution of educational level according to gender. Majority of eunuchs, i.e., 149 (72%), were illiterate followed by 39 (17.9%) males and 26 (12.1%) females. Highest number of males, i.e., 47 (21.6%) attended high school, whereas 54 (25.2%) females attended middle school. The difference in the distribution of educational level among males, females and eunuchs was statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Distribution of educational level of subjects according to gender

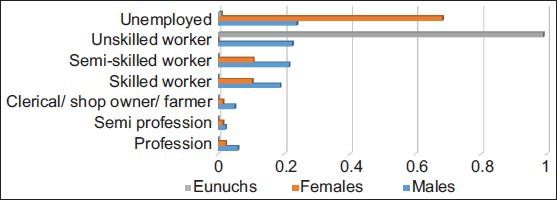

Figure 2 shows distribution of occupation according to gender. Among the study participants, 146 (68.2%) females, 52 (23.9%) males and 2 (1%) eunuchs were unemployed. However, 205 (99%) eunuchs, 49 (22.5%) males and 12 (5.6%) females were unskilled workers. The difference in distribution of occupation among the gender was statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Distribution of occupation according to gender

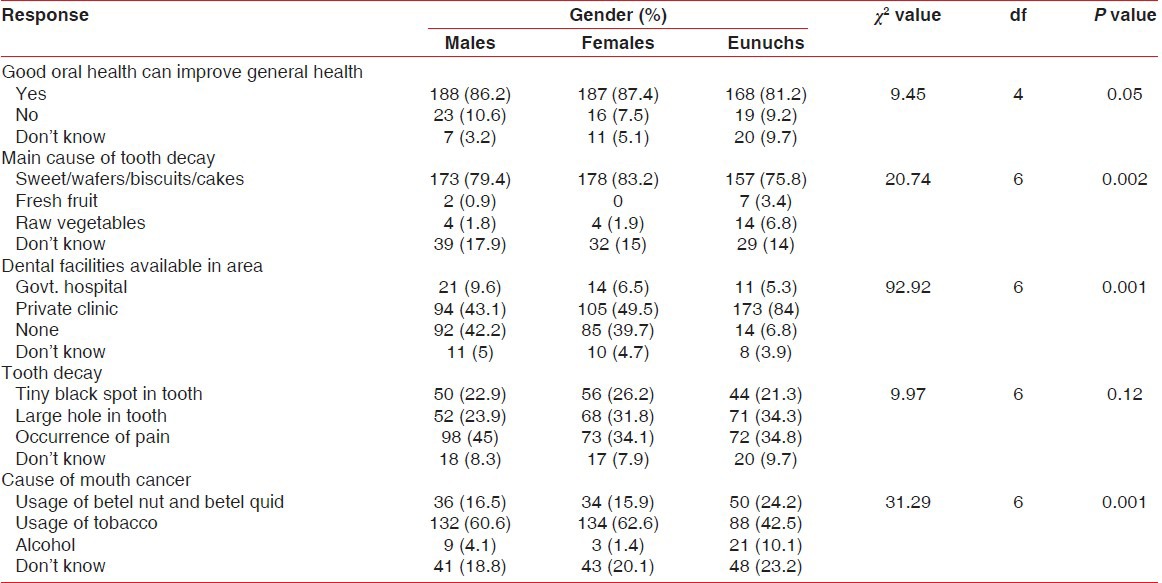

Knowledge

Table 1 shows the knowledge of subjects related to oral health and diseases. According to 188 (86.2%) males, 187 (87.4%) females and 168 (81.2%) eunuchs, good oral health can improve the general health. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.05).

Table 1.

Knowledge of subjects related to oral health and diseases

A majority of the study participants, i.e., 178 (83.2%) females, 173 (79.4%) males, and 157 (75.8%) eunuchs, felt that consumption of sweet/wafers/biscuits/cakes causes a tooth decay. However, 39 (17.9%) males, 32 (15%) females and 29 (14%) eunuchs were unaware about the cause of tooth decay. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.002).

In response to a question related to dental facilities available in the area, a majority of eunuchs, i.e., 173 (84%), followed by 105 (49.5%) females, and 94 (43.1%) males, said that there is an availability of private dental clinic in their area. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

A majority of the study participants including 98 (45%) males, 72 (34.8%) eunuchs and 71 (34.1%) females believed that tooth decay can be identified when there is an occurrence of pain. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.12).

In a reply to the question related to cause of cancer, 134 (62.6%) females, 132 (60.6%) males, and 88 (42.5%) eunuchs said that usage of tobacco is the main cause of cancer. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

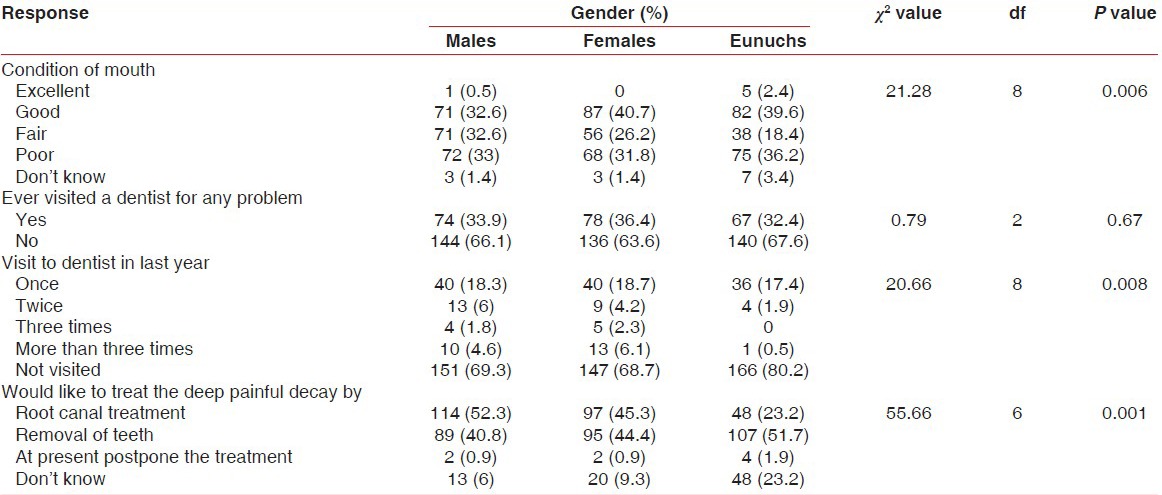

Attitude

Table 2 shows attitude of subjects toward oral health and hygiene. A majority of females, i.e., 87 (40.7%), followed by 82 (39.6%) eunuchs and 71 (32.6%) males believed that condition of their mouth was good. However, 75 (36.2%) eunuchs, 72 (33%) males, and 68 (31.8%) females thought condition of their mouth was poor. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.006).

Table 2.

Attitude of subjects towards oral health and hygiene

Most of the females, i.e., 78 (36.4%) have previously visited a dentist. However, 140 (67.6%) eunuchs and 144 (66.1%) males have never visited a dentist. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.67).

In response to a question related to visit to a dentist in last year, 166 (80.2%) eunuchs followed by 151 (69.3%) males and 147 (68.7%) females said that they have not visited a dentist in last year. The difference in a visit was statistically significant (P < 0.008).

Highest of 114 (52.3%) males and 97 (45.3%) females said that they would like to prefer a root canal treatment to treat a deep painful decay. While highest of 107 (51.7%) eunuchs said that they would like to remove the tooth. The difference in choice of treatment was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Practice

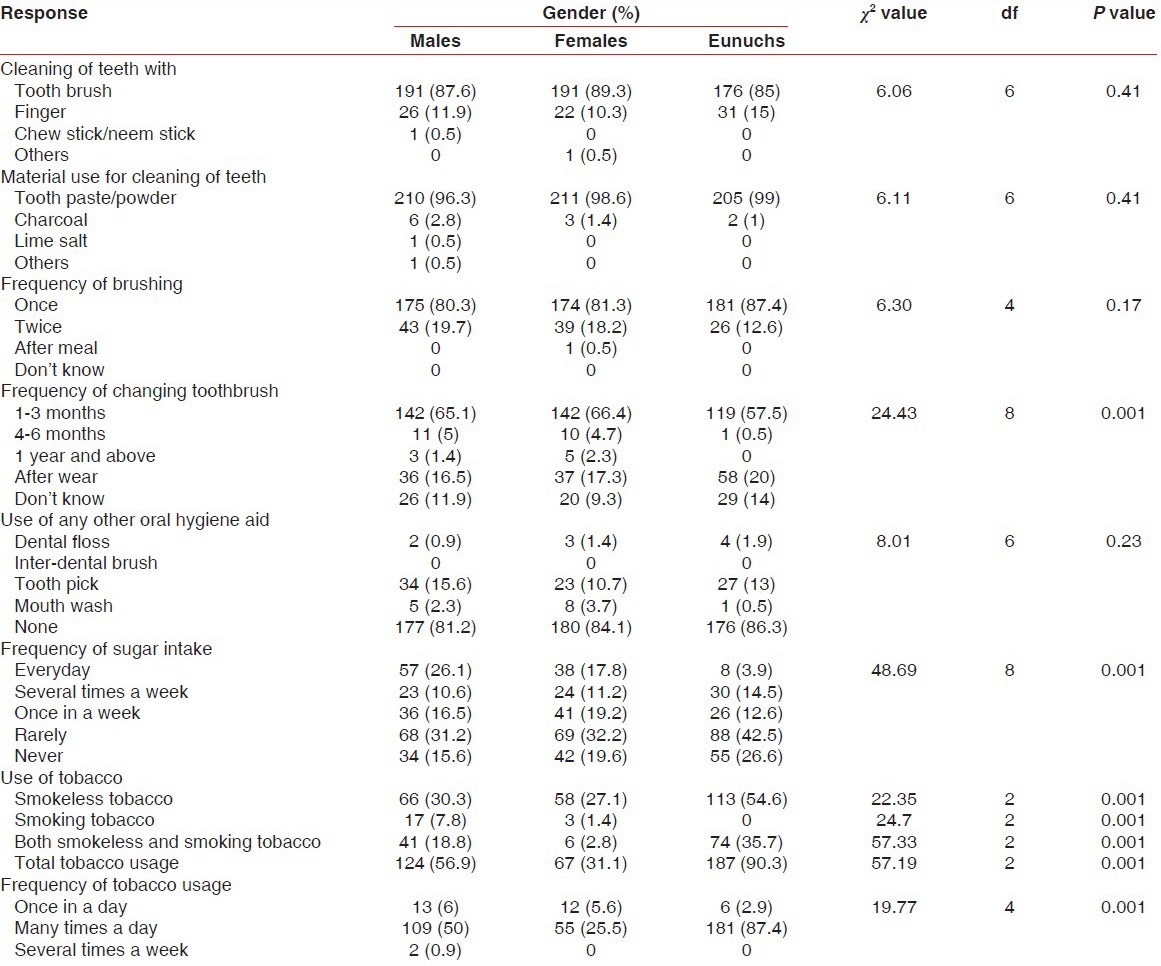

Table 3 shows oral hygiene practices among subjects. The highest number of participants, i.e., 191 (89.3%) females, 191 (87.6%) males and 176 (85%) eunuchs clean their teeth with a toothbrush. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.41).

Table 3.

Oral hygiene practices among subjects

Most of the study participants including 211 (98.6%) females, 210 (96.3%) males and 205 (99%) eunuchs use either tooth paste or tooth powder to clean their teeth. There difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.41).

A total of 181 (87.4%) eunuchs followed by 174 (81.3%) females and 175 (80.3%) males brush their teeth daily once. The difference in frequency of brushing was not statistically significant (P = 0.17).

Among all study participants, 142 (66.4%) females and 142 (65.1%) males followed by 119 (57.5%) eunuchs change their toothbrush within 1-3 months. However, 58 (20%) eunuchs, 37 (17.3%) females and 36 (16.5%) males change their toothbrush after it wears. The difference in changing the toothbrush among gender was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Other than toothbrush, 34 (15.6%) males, 27 (13%) eunuchs and 23 (10.7%) females use tooth pick to clean their teeth. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

In a reply to a question related to frequency of sugar intake, a majority of eunuchs, i.e., 88 (42.5%) followed by 69 (32.2%) females and 68 (31.2%) males, were taking sugary food rarely. While 57 (26.1%) males, 38 (17.8%) females, and 8 (3.9%) eunuchs were consuming sugar-containing food every day. The difference in frequency of sugar intake was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

A majority of eunuchs, i.e., 113 (54.6%), were having habit of chewing smokeless tobacco containing products such as betel nut, betel quid, gutkha, etc., this was followed by 66 (30.3%) males and 58 (27.1%) females. However, 74 (35.7%) eunuchs, 41 (18.8%) males and 6 (2.8%) females were habitual to both smokeless and smoking tobacco products. The difference in use of tobacco products was statistically significant. (P < 0.001)

In a response to frequency of tobacco usage; 181 (87.4%) eunuchs, 109 (50%) males and 55 (25.5%) females said that they were taking tobacco many times a day. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The current cross-sectional, questionnaire survey was conducted with the aim of assessing oral health-related knowledge, attitude, and practices among eunuchs residing in Bhopal city. This was the unique, first of its kind, pioneering study which revealed the oral health-related information of eunuch/Hijra/third gender community. A total of 639 subjects comprising of 207 eunuchs, 218 males and 214 females were recruited in the study.

A different sampling technique, i.e., “snowball sampling” was adopted for this study. As eunuch (Hijra) community is highly secretive and hidden community, very little is known about them. Such kind of ‘Hidden populations’ have two characteristics: First no sampling frame exists, so the size and boundaries of the population are unknown; and second, there exist strong privacy concerns, because membership involves stigmatized or illegal behavior, leading individuals to refuse to co-operate or give unreliable answers to protect their privacy.[16] Traditional methods, such as household surveys, cannot produce reliable samples, and they are inefficient, because most hidden populations like eunuchs are rare. Accessing such populations is difficult because standard probability sampling methods produce low response rates and responses that lack candor.[17] Because of these reasons snowball sampling was the best method available for our study.

The major problem we faced while comparing the data was lack of literature on eunuchs. So we have made sincere efforts to compare the results of other studies on general population.

In the present study, an interviewer-based 18-item, close-ended questionnaire was used to assess subject's knowledge, attitude and behavior related to oral health and diseases. The awareness on the causative factors for periodontal and other dental diseases, the attitude, oral health-related habits, and behaviors plays a vital role in determining the oral health status of individuals.[18,19] The scientific literature offers conflicting results on the impact of oral health knowledge, attitude and oral health behavior on oral diseases. However, collection of such data has been helpful in planning preventive oral health education programs targeted toward health professionals.

It was found that the level of knowledge was high among genders with more than 80% believed that oral health affects general health. This vital concept was for the first time highlighted by the World Health Organization to educate the public about the manner in which oral health influences the overall health.[20] Females (83.2%) slightly have a more knowledge of food that causes dental caries, this coincides with results showed by Basser et al.[21] However, eunuchs (96%) were more aware of the dental facilities available in their area. This could be correlated with the way of earning of eunuch community. As all of them earn through ‘basti’ or ‘mangti’ (kind of begging), for this they always explore and visit nearby places. It can be observed that majority of eunuchs (58.5%) were unaware of tobacco as a cause of cancer. Tobacco has also been found to be a major environmental factor associated with generalized forms of severe periodontitis in several studies.[2,5,20] The low awareness of tobacco as a risk factor among eunuchs could be attributed to their low level of education. A similar factor was assessed in studies conducted by Lawoyin et al.[22] and Horowitz et al.[23]

In general, females were having relatively more oral health-related knowledge but the difference between males and females was not statistically significant. This finding is similar with results reported by Khami et al.[24] in which males and females showed no differences. However, our study also revealed that there was statistically significant difference between knowledge of males, females as compared with eunuchs, which suggested that eunuchs have lower oral health-related knowledge in comparison with males and females. This can be attributed to level of education, as majority of the eunuchs were illiterate (72%).

Attitude toward professional dental care varied among the gender. Higher number of females and eunuchs showed a positive attitude toward condition of their mouth. However, all three genders showed a negative attitude toward regular visit to dentist. These findings are similar to the study conducted by Zhu et al.[25] in which significant proportions of study participant had never seen a dentist. Similar finding also showed that significantly higher proportion of eunuchs, i.e., 80.2% have not visited a dentist in last year. Overall, majority of, i.e., 60% of population said that toothache was the driving factor for visiting the dentist and there was no statistically significant difference found among gender. This finding coincides with the study reported by Zhu et al.[25] in which toothache was the major driving force for visit to dentist. This was attributed to lower socioeconomic status of individuals. The high cost of sophisticated dental services may discourage the subjects in the lower class not to have a dental visit on a routine basis. They reserve the dental visit for an acute problem when all other possible methods to alleviate the existing problem have completely failed.[26] This in the long run may result in the development of a negative attitude toward dentist and dental procedures among the people in lower classes. This suggests a bidirectional adverse relationship between attitude, dental visits, and awareness on the causative factors for dental diseases. Other finding related to attitude was: Majority of eunuchs (51.7%) believed that treatment of painful tooth is extraction. However, a higher percentage of male and female population believed that the extraction of a painful tooth is not the ultimate remedy for pain relief. This shows that they may be aware of other available treatment options for curing tooth pain compared to eunuchs. This perception was found to be significantly associated with education level of the participants which shows that they are better informed about oral health issues.[25]

Oral hygiene practices have often been closely intertwined with religion and ritual practices, especially in widely diverse country like India. These practices are the activities undertaken by people to protect, promote or maintain health and to prevent chronic diseases. Generally, dental health behaviors have been categorized according to “brushing behavior” and “complex dental behavior.”[27] The effective tooth-cleaning practices are indicative of positive oral health behavior, whereas frequent consumption of improper food represents negative health behavior (risk behavior).[28]

Appropriate use of mechanical plaque control aids is significantly associated with prevention of gingival and periodontal diseases. In the present study, more than 85% of the study subjects used toothpaste and toothbrush to clean their teeth. The percentage is lower compared to study reported by Sharda and Shetty[29] and Doshi et al.[30] in which 96.7% and 100% of the participants were using tooth brush and toothpaste. Higher level of oral hygiene practices in our study would have been observed if oral health education, promotion and preventive programs had been carried out in communities that lack access to care. This helps in ‘developing personal skills’[31] of individuals and the society, which can be achieved by the help of community healthcare professionals. In relation to the frequency of brushing, more than 80% subjects brushed their teeth once in the morning every day and there was no statistically significant difference found among gender. A high percentage of subjects brushed their teeth twice daily in previous studies[32,33] when compared with the present study. Among the users of other oral hygiene aids, the highest use of mouthwash was done by 3.7% of females, while, 15.2% males used toothpick and 1.4% eunuchs used dental floss. These findings indicate very low usage of other oral hygiene aids among study subjects. Reason behind this can be attributed to low socioeconomic status of individuals. Besides, the lack of affordability to buy the oral hygiene aids may prompt the people in the lower classes to escape from use of oral hygiene aids.

The frequency of sugar exposure among study participants was very low especially, among eunuchs population. More than 69% eunuchs either took sugar rarely or never, this was followed by 51% females and 47% males. The difference in sugar intake was statistically significant among gender. This result is in contrast with results of Zhu et al.[25] which showed higher frequency of daily eating sweets in urban population (55%). Low socioeconomic status can be a major factor behind this.

This study revealed an important finding that there was a marked rise in consumption of tobacco (smoking and non-smoking) and associated products (gutkha, paan masala, khaini, areca nut, etc.) among eunuch (90.3%) and male (56.9%) population. Similarly, the frequency of consuming these products many times a day was found most among eunuchs, i.e., 87.4% followed by 50% males. The higher usage of tobacco among eunuchs and males can be correlated with occupation. It has been shown that occupation influences individual's tobacco use. A large proportion of the females in this sample were homemakers while males and eunuchs were the major working groups. Individuals working are found to be highly associated with the habit, as they felt that it reduces the tiredness and brought in excitement in the body after heavy labor work.[34] Similarly, psychosocial stress due to an unfavorable social position, the lack of awareness on the ill effects of these habits, scarce material resources, and poor material conditions may have a contributing role behind a very high use of tobacco products among eunuchs. These findings indicate a need for awareness of the risk factors of periodontitis requires wide-ranging educational interventions which should be directed toward the less-educated eunuch population.

In general, the level of dental health knowledge, positive dental health attitude, and dental health behaviors are interlinked and positively associated with the level of education as an educated individual gains the requisite knowledge from multiple sources.[35,36] So, there is an immediate need of developing both promotive and preventive strategies directed toward eunuchs which may facilitate in improving their periodontal as well as other dental health knowledge. This in turn will drive this socially stigmatized community to have a positive dental health attitude and behavior.

CONCLUSION

The results of the present study provide important information about oral health-related knowledge, attitude and practices among eunuch community residing in Bhopal city. The information presented in this study adds to our understanding of the common oral hygiene practices which are performed among eunuch population. It was found that, eunuchs have poor oral health-related knowledge, attitude and practices along with higher prevalence of tobacco-related habits. Efforts to increase the awareness of oral effects of tobacco use and to eliminate the habit are needed to improve oral and general health of this population. The results of this study should serve as the basis for a larger, nation-wide survey of oral lesions among socially deprived communities like eunuchs.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kwan SY, Petersen PE, Pine CM, Borutta A. Health-promoting schools: An opportunity for oral health promotion. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:677–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen PE, Kwan S. Evaluation of community-based oral health promotion and oral disease prevention--WHO recommendations for improved evidence in public health practice. Community Dent Health. 2004;21(Suppl 4):319–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen MS. Children's preventive dental behavior in relation to their mother's socioeconomic status, health beliefs, and dental behaviors. J Dent Child. 1986;53:105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman LA, Mackler IG, Hoggard GJ. A comparison of perceived and actual dental needs of a selected group of children in Texas Community. Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1976;4:89–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1976.tb02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCaul KD, Glasgow RE, Gustafson C. Predicting levels of preventive dental behaviors. J Am Dent Assoc. 1985;111:601–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1985.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright FA. Children's perception of vulnerability to illness and dental disease. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1982;10:29–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1982.tb00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steptoe A, Wardle J, Vinck J. Personality and attitudinal correlates of healthy and unhealthy lifestyles in young adults. Psychol Health. 2004;9:331–43. doi: 10.1080/08870449408407492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharda AJ, Shetty S. A comparative study of oral health knowledge, attitude and behaviour of first and final year dental students of Udaipur city, Rajasthan, India. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:347–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh A, Bharathi MP, Swqueira P, Acharya S, Bhat M. Oral health status and practices of 5 and 12 year old Indian tribal children. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2011;13:32530. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.35.3.c8063171438k4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandrima C, Gunjan S. Hijra status in India. In: Chatterjee C, editor. Vulnerable groups in India. 1st ed. Mumbai: Publisher Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes; 2007. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders AE, Spencer AJ. Social inequality in perceived oral health among adults in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28:159–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2004.tb00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nanda S. The hijra of India. In: Nanda S, editor. Neither man nor woman. 2nd ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing; 1999. pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jennifer L. Borrowing religious identifications: A study of religious practices among the Hijras of India. Polyvocia–The SOAS Journal of Graduate Research. 2011;3:50–67. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Human Rights Defence, Inc; c2005-06. [Last updated on 2005 May 16; Cited on 2011 Sept 22]. Eunuchs of India. Available from: http://www.humanrightsdefence.org/eunuchs-of-india-deprived-of-human-rights.html . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naghma R, Chaudhary I, Shah SK. Socio-sexual Behaviour of Hijras of Lahore. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:380–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heckathorn DD. Respondent- driven sampling: Anew approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44:174–99. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodman LA. “Snowball sampling”. Ann Math Stat. 1961;32:148–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burt BA. Trends in caries prevalence in North American children. Int Dent J. 1994;44:403–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen PE, Christensen LB, Moller IJ, Johansen KS. Continuous improvement of oral health in Europe. J Ir Dent Assoc. 1994;40:105–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheiham A. Oral health, general health and quality of life. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:644. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Omari QD, Hamasha AA. Gender-specific oral health attitudes and behavior among dental students in Jordan. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:107–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawoyin JO, Aderinokun GA, Kolude B, Adekoya SM, Ogundipe BF. Oral cancer awareness and prevalence of risk behaviours among dental patients in South-western Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2003;32:203–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horowitz AM, Moon HS, Goodman HS, Yellowitz JA. Maryland adults’ knowledge of oral cancer and having oral cancer examinations. J Public Health Dent. 1998;58:281–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1998.tb03010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khami MR, Virtanen JI, Jafarian M, Murtomaa H. Prevention-oriented practice of Iranian senior dental students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2007;11:48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2007.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu L, Petersen PE, Wang HY, Bian JY, Zhang BX. Oral health knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of adults in China. Int Dent J. 2005;55:231–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2005.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trihart AH. Understanding the underprivileged child: Report of an experimental workshop. J Am Dent Assoc. 1968;77:880–3. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1968.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rise J, Holund U. Prediction of sugar behavior. Community Dent Health. 1990;7:267–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cynthia MP. Principles of oral health promotion. In: Cynthia MP, editor. Community Oral Health. 2nd ed. Berlin: Reed Educational and Professional Publishing Ltd; 2007. pp. 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharda AJ, Shetty S. A comparative study of oral health knowledge, attitude and behaviour of non-medical, Para-medical and medical students in Udaipur city, Rajasthan, India. Int J Dent Hyg. 2010;8:101–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2009.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doshi D, Baldava P, Sequeira PS, Anup NA. Comparative evaluation of self-reported oral hygiene practices among medical and engineering university students with access to health promotive dental care. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2007;8:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO, Inc; c2000-01. [Last updated on 2000 Jan 16; Cited on 2013 Aug 06]. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en . [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maatouk F, Maatouk W, Ghedira H, Ben Mimoun S. Effect of five years of dental studies on the oral health tunisian dental students. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12:625–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-shammari KF, Al-Ansari JM, Al-Khabbaz AK, Dashti A, Honkala EJ. Self-reported oral hygiene habits and oral health problems of Kuwaiti adults. Med Princ Pract. 2007;16:15–21. doi: 10.1159/000096134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasat V, Joshi M, Somasundaram KV, Viragi P, Dhore P, Sahuji S. Tobacco use, its influences, triggers, and associated oral lesions among the patients attending a dental institution in rural Maharashtra, India. J Int Soc Prevent Communit Dent. 2012;2:25–30. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.103454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Wahadni AM, Al-Omiri MK, Kawamura M. Differences in self-reported oral health behavior between dental students and dental technology/dental hygiene students in Jordan. J Oral Sci. 2004;46:191–7. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.46.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrieshi-Nusair K, Alomari Q, Said K. Dental health attitudes and behaviour among dental students in Jordan. Community Dent Health. 2006;23:147–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]