Abstract

Anatomically the pulp and periodontium are connected through apical foramen, and the lateral, accessory, and furcal canals. Diseases of one tissue may affect the other. In the present case report with two cases, a primary periodontal lesion with secondary endodontic involvement is described. In both cases, root canal treatment was done followed by periodontal therapy with the use of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) as the regenerative material of choice. PRF has been a breakthrough in the stimulation and acceleration of tissue healing. It is used to achieve faster healing of the intrabony defects. Absence of an intraradicular lesion, pain, and swelling, along with tooth stability and adequate radiographic bone fill at 9 months of follow-up indicated a successful outcome.

Keywords: Combined lesion, endo-perio lesion, intrabony defect, platelet-rich fibrin, regeneration, sole filling material

INTRODUCTION

The tooth, the pulp tissue within it, and its supporting structures should be viewed as one biologic unit. The interrelationship between periodontal and endodontic diseases has aroused much speculation, confusion, and controversy. The relationship between the periodontium and the pulp was first discovered by Simring and Goldberg in 1964.[1] The periodontium and pulp have embryonic, anatomic, and functional interrelationship. Ectomesenchymal cells proliferate to form the dental papilla and follicle, which are the precursors of the periodontium and the pulp, respectively. This embryonic development gives rise to anatomic connections, which remain throughout life.[2]

Etiologic factors such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses, as well as various contributing factors such as trauma, root resorptions, perforations, and dental malformations play an important role in the development and progression of endo-perio lesion. The endo-perio lesion is a condition characterized by the association of periodontal and pulpal disease in the same dental element. The term “perio-endo lesion” is used to describe lesions formed due to inflammatory products found in varying degrees in both periodontium and pulpal tissues.[3]

Other than these microbial findings, similarities in the composition of cellular infiltrates also suggest the existence of communication between the pulp and the periodontal tissues.[4,5] The possible pathways for the ingress of bacteria and their products into these tissues can broadly be divided into: Anatomic and physiological pathways.[6] The causative agents of periodontal disease are found in the sulcus and are continually challenged by host defenses. An immunologic or inflammatory response is elicited in response to this microbiologic challenge. When periodontal disease extends from the gingival sulcus toward the apex, the inflammatory products attack the elements of the periodontal ligament and the surrounding alveolar bone.[7]

Periodontal therapy is performed to remove the local factors, which leads to resolution of inflammation in the supporting structures of the tooth. It predominantly involves scaling and root planing as a main therapy, combined with hard and soft tissue surgery. With proper postoperative maintenance care, resolution of inflammation occurs, leading to arrest of disease progression.[8]

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

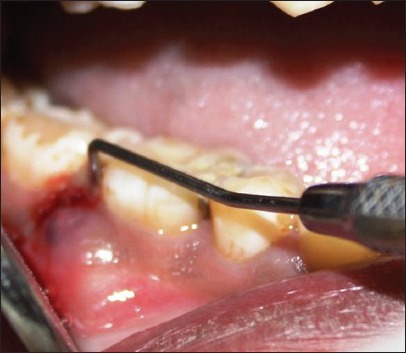

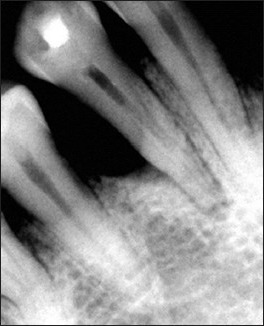

A 24-year-old male patient reported to the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics with the chief complaint of pain in the lower right back tooth region since 1 month. The medical history was non-contributory. On clinical examination, there was inflammation of attached gingiva, pus discharge, and pain on percussion with a probing depth of about 10 mm in relation to 46 [Figure 1]. Pulp sensitivity testing was performed using hot and cold tests in which the tooth gave a negative response indicating it to be non-vital. Radiographic examination revealed severe bone loss around the distal aspect of the tooth [Figure 2], diagnosed as primary periodontal lesion with secondary endodontic involvement. The initial phase of treatment comprised drainage of abscess, and scaling and root planing; also, antibiotics (amoxicillin 500 mg, 3 times a day for 5 days) and analgesics (ibuprofen 400 mg, 3 times a day for 3 days) were prescribed. Initially, root canal therapy was performed [Figure 3]. After 3 months, the patient was recalled and regenerative surgical procedure was planned for the treatment of intrabony defect using platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) as the regenerative material of choice which served as a filling material as well as a membrane [Figures 4-8]. After a follow-up period of 9 months, the probing depth reduced from 10 to 4 mm and radiographically there was considerable bone formation [Figures 9 and 10].

Figure 1.

Preoperative clinical situation showing 46, 47

Figure 2.

Preoperative radiograph of tooth 46 showing intrabony defect at the distal aspect radiolucency extending till the apical third

Figure 3.

Obturation radiograph

Figure 4.

Flap reflection

Figure 8.

PRF as GTR membrane

Figure 9.

Six months postoperative view showing reduced pocket depth

Figure 10.

Six months follow-up radiograph

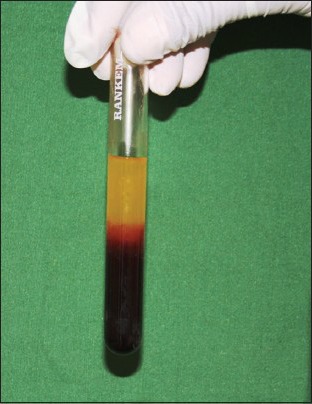

Figure 5.

PRF gel with different layers

Figure 6.

PRF

Figure 7.

PRF as the sole filling material

Case 2

A 32-year-old female patient reported to the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics with the chief complaint of pain in the lower right back tooth region since 2 months. The medical history was non-contributory. On clinical examination, there was grade I mobility and pain on percussion with a probing depth of 8 mm in relation to 44. Pulp sensitivity testing was performed in which the tooth gave a negative response indicating it to be non-vital. Radiographic examination revealed severe bone loss around the distal aspect of the tooth 44 [Figure 11], diagnosed as primary periodontal with secondary endodontic lesion. The initial phase of treatment consisted of complete scaling and root planing. Initially, root canal therapy was performed in relation to 46. Three months later, the patient was recalled for management of intrabony defect using PRF as the material of choice for regeneration of tissues [Figures 12 and 13]. After 9 months follow-up period, there was an evidence of bone formation and the probing depth reduced to 3 mm [Figure 14.]

Figure 11.

Preoperative radiograph of tooth 44 showing intrabony defect on the distal aspect

Figure 12.

Flap reflection

Figure 13.

PRF as the sole filling material

Figure 14.

Nine months follow-up radiograph

DISCUSSION

Perio-endo lesions develop by either periodontal destruction combining apically with an existing periapical lesion or an endodontic lesion combining with an existing periodontal lesion.[3] Seltzer et al.[9] concluded that an established endodontic lesion could progress through the main or accessory canals to produce periodontal breakdown. A more controversial hypothesis has also been suggested, which is the spread of infection from a periodontal pocket into the root canal system itself.[10] True-combined lesions are treated initially as for primary endodontic lesions with secondary periodontal involvement. Periodontal surgical procedures are almost always called for. The prognosis of a true-combined perio-endo lesion is often poor or even hopeless, especially when periodontal lesions are chronic with extensive loss of attachment.[11] The prognosis of an affected tooth can also be improved by increasing the bony support, which can be achieved by bone grafting[12] and guided tissue regeneration (GTR)[13] and the application of polypeptide growth factors to the surgical wound. These are some of the commonly used techniques to promote periodontal regeneration. This is due to the most critical determinant of prognosis being loss of periodontal support. These advanced treatment plans are based on responses to conventional and endodontic treatment over an extended time period.

El-sharkawy et al.[14] studied the regenerative potential of PRF and suggested that the administration of growth factors may be combined with tissue regeneration techniques in the repair of intrabony defects, furcations, and cyst cavities. To improve the outcome of these treatments, clinicians and scientists are investigating the use of PRF in dentistry as a way to enhance the body's natural wound healing mechanisms.

PRF is a regenerative material that was first developed by Choukroun et al. in France in 2001.[15] It belongs to the new generation of platelet concentrates which is in the form of a platelet gel. It is made from autologous blood and is used to deliver growth factors in high concentration to the site of a bone defect, offering several advantages including promoting wound healing, bone growth, maturation, graft stabilization, wound sealing, and hemostasis.[15]

PRF has been shown to be superior over traditionally prepared platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Its advantages include ease of preparation and lack of biochemical handling of blood which makes this preparation strictly autologous. The step in which bovine-derived thrombin is added to promote conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin in PRF is eliminated. The elimination of this step considerably reduces the risk associated with the use of bovine-derived thrombin. The conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin takes place slowly with small quantities of physiologically available thrombin present in the blood sample itself. Thus, the physiological architecture that is very favorable to the healing process is obtained due to this slow polymerization process.[15]

It consists of a fibrin matrix polymerized in a tetramolecular structure with incorporation of platelets, leukocytes, cytokines, and circulating stem cells.[16] The intrinsic incorporation of cytokines within the fibrin mesh allows for their progressive release over time (7-10 days) as the network of fibrin disintegrates.[16] According to Simonpieria et al.,[15] the use of this platelet and immune concentrate offers the following four advantages. First, the fibrin clot plays an important mechanical role, with the PRF membrane maintaining and protecting the grafted biomaterials and PRF fragments serving as biological connectors between bone particles. Second, the integration of this fibrin network into the regenerative site facilitates cellular migration, particularly for the endothelial cells necessary for neoangiogenesis, vascularization, and survival of the graft. Third, the platelet cytokines [platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor (TGF), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)] are released gradually as the fibrin matrix gets resorbed, thus creating a perpetual process of healing. Lastly, the presence of leukocytes and cytokines in the fibrin network can play a significant role in the self-regulation of inflammatory and infectious phenomenon within the grafted material.[17]

Anderegg et al.[18] showed that the vertical component of the defect can predict the extent of osseous repair following regenerative surgery.

The cases presented here were more amenable to regenerative therapy than root resection. Lack of mobility and presence of good bone support on the buccal side were the factors that favored the use of regenerative procedures instead of root resection. Periodontal therapy deals with many aspects of the supporting structures, including the prevention and repair of lesions of the gingival sulcus. Endodontic therapy deals primarily with diseases of the pulp and periapical tissues. The success of both periodontal and endodontic therapy depends on the elimination of both disease processes, whether they exist separately or as a combined lesion. The relationship between periodontal and endodontic disease has been a subject of speculation for many years.

In the cases discussed here, endodontic therapy was performed first, followed by periodontal therapy after 3 months. This sequence of treatment allows sufficient time for initial tissue healing and better assessment of the periodontal condition. It also reduces the potential risk of infection with bacteria and their by-products in the initial healing phase.[17] Here, PRF is used as both a graft material as well as a membrane. The postoperative radiograph taken at the 9 months follow-up examination showed complete resolution of the periapical lesion and bone fill of the intrabony defect. Endodontic therapy resulted in resolution of the endodontic lesion, but had little effect on the periodontal lesion. Therefore, it is essential that the periodontal problem is also treated to obtain the optimal therapeutic outcome.

CONCLUSION

Results of the cases presented here show that the combined treatment approach with PRF was effective in treating the intrabony defects as well as combined perio-endo lesions. Ideal ratios of the components of PRF preparation are still being investigated, and more clinical researches are required to assess the long-term effectiveness of this combined therapy as an adjunct to endodontic therapy in the treatment of combined defects.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Simring M, Goldberg M. The pulpal pocket approach: Retrograde periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1964;35:22–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandel E, Machton P, Torabinejad M. Clinical diagnosis and treatment of endodontic and periodontal lesions. Quintessence Int. 1993;24:135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh P. Endo-perio dilemma: A brief review. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2011;8:39–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kipioti A, Nakou M, Legakis N, Mitis F. Microbiological findings of infected root canals and adjacent periodontal pockets in teeth with advanced periodontitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:213–20. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergenholtz G, Lindhe J. Effect of experimentally induced marginal periodontitis and periodontal scaling on the dental pulp. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:59–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1978.tb01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zehnder M, Gold SI, Hasselgren G. Pathologic interactions in pulpal and periodontal tissues. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:663–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunitha VR, Emmadi P, Namasivayam A, Thyegarajan R, Rajaraman V. The periodontal-endodontic continuum: A review. J Conserv Dent. 2008;11:54–62. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.44046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon JH, Glick DH, Frank AL. The relationship of endodontic periodontic lesions. J Periodontol. 1972;43:202–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.4.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seltzer S, Bender IB, Nazimov H, Sinai I. Pulpitis induced interradicular periodontal changes in experimental animals. J Periodontal. 1967;38:124–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meister F, Jr, Lommel TJ, Gerstein H, Davies EE. Endodontic perforations which resulted in alveolar bone loss. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;47:463–70. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christie WH, Holthuis AF. The endo-perio problem in dental practice: Diagnosis and prognosis. J Can Dent Assoc. 1990;56:1005–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zubey Y, Kozlovsky A. Two approaches to the treatment of true combined periodontal-endodontal lesions. J Endod. 1993;19:414–6. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tseng CC, Harn WM, Chen YH, Huang CC, Yuan K, Huang PH. A new approach to the treatment of true-combined endodontic-periodontic lesions by the guided tissue regeneration technique. J Endod. 1996;22:693–6. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(96)80067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-sharkawy H, Kantarci A, Deady J, Hasturk H, Liu H, Alshahat M, et al. Platelet rich plasma: Growth factors and pro- and anti-inflammatory properties. J Periodontol. 2006;78:661–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corso MD, Toffler M, Ehrenfest DM. Use of an autologous leukocyte and plate let-rich fibrin (L-PRF) membrane in post – avulsion sites: An overview of Choukroun's PRF. J Implant Adv Clin Dent. 2010;9:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kathuria A, Chaudhry S, Talwar S, Verma M. Endodontic management of single rooted immature mandibular second molar with single canal using MTA and platelet-rich fibrin membrane barrier: A case report. J Clin Exp Dent. 2011;3:e487–90. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Del Corso M, Diss A, Mouhyi J, Charrier JB. Three-dimensional architecture and cell composition of a Choukroun's platelet-rich fibrin clot and membrane. J Periodontol. 2010;81:546–55. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderegg CR, Martin SJ, Gray JL, Mellonig JT, Gher ME. Clinical evaluation of the decalcified freeze dried bone allograft with guided tissue regeneration in the treatment of molar furcation invasions. J Periodontol. 1991;62:264–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.4.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]