Abstract

Our understanding of fungal cellulose degradation has shifted dramatically in the past few years with the characterization of a new class of secreted enzymes, the lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMO). After a period of intense research covering structural, biochemical, theoretical and evolutionary aspects, we have a picture of them as wedge-like copper-dependent metalloenzymes that on reduction generate a radical copper-oxyl species, which cleaves mainly crystalline cellulose. The main biological function lies in the synergism of fungal LPMOs with canonical hydrolytic cellulases in achieving efficient cellulose degradation. Their important role in cellulose degradation is highlighted by the wide distribution and often numerous occurrences in the genomes of almost all plant cell-wall degrading fungi. In this review, we provide an overview of the latest achievements in LPMO research and consider the open questions and challenges that undoubtedly will continue to stimulate interest in this new and exciting group of enzymes.

Keywords: AA9, GH61, cellobiose dehydrogenase, oxidative cellulose degradation

INTRODUCTION

It is not often seen in the biochemical literature that enzymes are described as enigmatic, elusive, puzzling or mysterious. Yet, until recently all these terms have been used by researchers to describe an enzyme family that we now know plays an important role, together with classical cellulases, in the degradation of crystalline polysaccharides. The enzymes are the lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs), a term coined by Horn et al. [1]. LPMOs comprise three families, although examples from only two families have been characterized in detail. One family contains only fungal enzymes belonging to the former glycoside hydrolase family 61 (GH61). The second family, formerly known as carbohydrate-binding module 33 (CBM33), is dominated by enzymes of bacterial and viral origin but is also reported to encompass a few enzymes from eukaryotes, namely, the fungus Sporisorium reilianum and the fern Tectaria macrodonta (Carbohydrate Active Enzymes database; http://www.cazy.org) [2]. The third LPMO family has only been described recently and shares important structural features with the two previously characterized families [3]. The only characterized member so far originates from Aspergillus oryzae and was shown to possess chitinolytic activity. A search in genome databases reveals that related sequences are widespread in genomes from ascomycetes but less common in basidiomycetes [3]. In the CAZy database, LPMOs are now classified as auxiliary activity family 9 (AA9, formerly GH61), family 10 (AA10, formerly CBM33) and family 11 (AA11) [2, 4, 5]. We will use in this review the AA terms, as they have been widely adopted in the contemporary literature, but we are not renaming characterized enzymes that have been coined using the old system. Table 1 lists the LPMO members that have their structure solved and/or have been biochemically characterized.

Table 1:

Overview of characterized AA9, AA10 and AA11 enzymes

| Organism | Uniprot ID | GenBank ID | Other names | PDB ID | Reaction type | Regio-selectivity | Modularity | Products (degree of polymerization) and References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | ||||||||

| A. oryzae | Q2UA85 | BAE61530 | AoAA11 | 4MAI | chitinolytic | C1 | AA11-X278 | 5–10 [3] |

| M. thermophila | G2QI82 | AEO60271 | MYCTH_112089 | cellulolytic | C1 | AA9 | 4–8 [6] | |

| M. thermophila | G2QAB5 | AEO56665 | MYCTH_92668 | cellulolytic | C1 | AA9 | 2–8 [6] | |

| N. crassa | Q7RWN7 | EAA26873 | NcLPMO9E | cellulolytic | C1 | AA9–CBM1 | 2–8 [6, 7] 3–7 [8] | |

| N. crassa | Q1K8B6 | EAA32426 | NcLPMO9D | 4EIR | cellulolytic | C4 | AA9 | 2–8 [6–8] |

| N. crassa | Q7SA19 | EAA33178 | NcLPMO9M | 4EIS | cellulolytic | C1, C4 | AA9 | 2–4 [6, 7] |

| N. crassa | Q7SHI8 | EAA36362 | NcLPMO9C | cellulolytic hemicellulolytic | C4 | AA9–CBM1 | 2–3 [9] 2–4 [6] | |

| N. crassa | Q1K4Q1 | EAA26656 | NcLPMO9F | cellulolytic | C1 | AA9 | 2–8 [6] | |

| N. crassa | Q7SCJ5 | EAA34466 | NCU00836 | cellulolytic | C1 | AA9-CBM1 | 2–6 [6] | |

| N. crassa | Q7S439 | EAA30263 | NCU02240 | cellulolytic | C4 | AA9-CBM1 | 2–5 [6] | |

| N. crassa | Q7S111 | EAA29018 | NCU07760 | cellulolytic | C1, C4 | AA9-CBM1 | 2–7 [6] | |

| P. chrysosporium | H1AE14 | BAL43430 | PcLPMO9D | 4B5Q | cellulolytic | C1 | AA9 | 4–10, 2–6 [10, 11] |

| P. anserina | B2B629 | CAP73254 | PaGH61A | cellulolytic | C1a, C4a | AA9-CBM1 | 2–5 [12] | |

| P. anserina | B2AVF1 | CAP68375 | PaGH61B | cellulolytic | C1a, C4a | AA9-CBM1 | 2–5 [12] | |

| T. aurantiacus | G3XAP7 | ABW56451 | TaGH61A | 3ZUD | cellulolytic | C1 | AA9 | 3–8 [13] |

| T. terrestris | G2RGE5 | AEO71030 | 3EJA | cellulolytic | n.d. | AA9 | n.d [14, 15] | |

| T. reesei | Q7Z9M7 | AAP57753 | 2VTC | cellulolytic | n.d. | AA9 | n.d. [16] | |

| Bacteria | ||||||||

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | E1UUV3 | CBI42985 | 2YOY | n.d. | n.d | AA10 | n.d [17] | |

| Bacillus licheniformes | Q62YN7 | AAU22121 | chitinolytic | C1 | AA10 | 6–9 [18] | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis | Q838S1 | AAO80225 | EfLPMO10A | 4A02 4ALC | chitinolytic | C1 | AA10 | 4–8 [19, 20] |

| Serratia marcescens | O83009 | AAU88202 | SmLPMO10A | 2BEM 2LHS | chitinolytic | C1 | AA10 | 6–9 [21–23] |

| Streptomyces coelicolor | Q9RJC1 | CAB61160 | ScLPMO10B | 4OY6 | cellulolytic chitinolytic | C1, C4 | AA10 | 2–9 [24] |

| Streptomyces coelicolor | Q9RJY2 | CAB61600 | ScLPMO10C | 4OY7 | cellulolytic | C1 | AA10-CBM2 | 3–7 [25] 6–8 [23] 2–7 [24] |

| Thermobifida fusca | Q47QG3 | AAZ55306 | TfLPMO10A | 4GBO | cellulolytic chitinolytic | C1, C4 | AA10 | 3–9 [24] |

| Thermobifida fusca | Q47PB9 | AAZ55700 | TfLPMO10B | cellulolytic | C1 | AA10-CBM2 | 6–9, 3–10 [23, 24] | |

| V. cholerae O1 | Q9KLD5 | AAF96709 | VcLPMO10B | 2XWX | n.d. | n.d. | AA10b | n.d. [26] |

Note. n.d. = not determined; aproducts reported in the presence of cellobiose dehydrogenase; bAdjacent to three C-terminal uncharacterized domains.

In the past 4 years, LPMOs have received steadily increasing attention as is evident from the burgeoning number of publications about them [27, 28]. An indication of their industrial importance lies in the fact that many key findings were first described in the patents literature before they were reported in peer-reviewed journals. Although the origin of interest in these enzymes stemmed from their ability to stimulate biomass hydrolysis by cellulase cocktails, given their diversity and widespread distribution there is much to be learned about the roles they play in carbon cycling. While several review articles covering LPMOs have been published in the past few years [29–31], fast-paced progress by several research groups warrants frequent re-evaluation of the status of this interesting group of enzymes.

With an estimated annual production of 1.5 × 1012 tons, cellulose is the most abundant natural polymer on earth, and the vast majority is of plant origin [32]. It consists of a chain of anhydrous glucose units, linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds. In plant cell walls, inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds contribute to the enormous tensile strength of cellulose fibrils. Both, degree of polymerization (DP) and degree of substitution (DS) contribute to the physicochemical characteristics of cellulose. Bundles of elementary cellulose fibrils form insoluble crystalline microfibrils that are surrounded and protected by hemicellulose and an amorphous lignin matrix, rendering them recalcitrant to microbial digestion. Cellulose chains contain highly ordered crystalline regions and less-ordered amorphous regions.

The high recalcitrance of plant cell walls stems from the properties and interlinkages of its primary components, cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin, hindering the use of lignocellulose-rich feedstocks in the fermentation process [33]. Cost-efficient conversion of polymeric compounds into fermentable sugars is a main obstacle to operating second-generation biorefineries economically [34]. The quest to improve the enzyme cocktails used in the industry is ongoing and has already led to a considerable reduction in operating costs of modern biorefineries. A key part of the strategy has been the use of LPMOs, which has allowed for reduced enzyme loading without reduced conversion rate [35].

This review highlights the recent developments that have changed considerably our understanding of cellulose degradation by filamentous fungi through the discovery of oxidative enzymes that attack polysaccharides, including cellulose. We focus specifically on the recently discovered fungal LPMOs, which were formerly termed GH61.

CELLULOSE DEGRADATION BY FUNGAL ENZYMES

Textbook knowledge about cellulose degradation identifies three types of enzyme activities, which are endo-acting cellulase (EC 3.2.1.4, endoglucanase), exo-acting cellulases (EC 3.2.1.91 and EC 3.2.1.176, cellobiohydrolase) and cellobiase (EC 3.2.1.21, β-glucosidases) [36]. These enzymes have in common that they all hydrolyze the β-1,4-glycosidic bond connecting d-glucose units. Theoretically, this enzyme assemblage is sufficient to degrade cellulose completely into glucose, and commercial cellulase mixtures typically include these enzymes in varying proportions. However, the crystalline portion of cellulose is only partially attacked by hydrolytic enzymes, and in practice, its degradation proceeds slowly and is incomplete. It was postulated early in cellulose degradation research that additional components must be present to achieve complete hydrolysis. Reese introduced in the 1950s the C1-Cx two-enzyme concept, recognizing that the terminal hydrolyzing step (‘Cx’ activity) creating small soluble molecules, such as glucose, depends on the action of a component (‘C1’) that renders native cellulose more accessible to the hydrolytic enzyme by shortening cellulose without generating soluble cellulo-oligomers [37, 38]. At the time both enzyme components were unknown; however, multiple hydrolyzing components had been identified and they were collectively labeled as ‘Cx’ [39]. Later, the concept was expanded by pointing out the role of an unknown oxidative enzyme disrupting the crystalline cellulose structure [40].

The enzymes ultimately identified as responsible for oxidation were incorrectly classified as endoglucanases and assigned to a new glycoside hydrolase family, GH61, based on a weak endoglucanase activity that was observed for one family member, EGIV from Trichoderma reesei, encoded by the gene egl4 [41, 42]. Weak endoglucanase activity was furthermore observed in related enzymes [43–45] but was found to be absent in another family member [46]. However, from the beginning there was some uneasiness about the assigned endoglucanase function, as the activity was several orders of magnitude lower than what had been observed in other endoglucanases. It seemed unlikely that a fungus encoding a diverse collection of powerful cellulases would depend on such a weak catalytic partner. Suggestions were even made that the reported activity was perhaps an artifact because of contamination with a conventional cellulase. Thus, although experiments measuring gene transcription in response to cellulose pointed to a role for AA9 family enzymes in its degradation, just what part they played in vivo remained something of a mystery for many years [42].

STRUCTURE

The publication of the first crystal structure of a fungal LPMO was an important step in resolving the functional nature of this protein family [16]. This structure, from the second identified AA9 from T. reesei, then called GH61B, lacks the C-terminal CBM present on GH61 enzymes investigated up to that point, including T. reesei GH61A. Its structure closely resembles that of the bacterial CBP21 protein from Serratia marcescens, obtained a few years earlier and then thought to be a non-catalytic chitin-binding protein [21]. Both structures share a fibronectin type III β-sandwich fold consisting of two antiparallel twisted β-sheets creating an immunoglobulin-like topology [16].

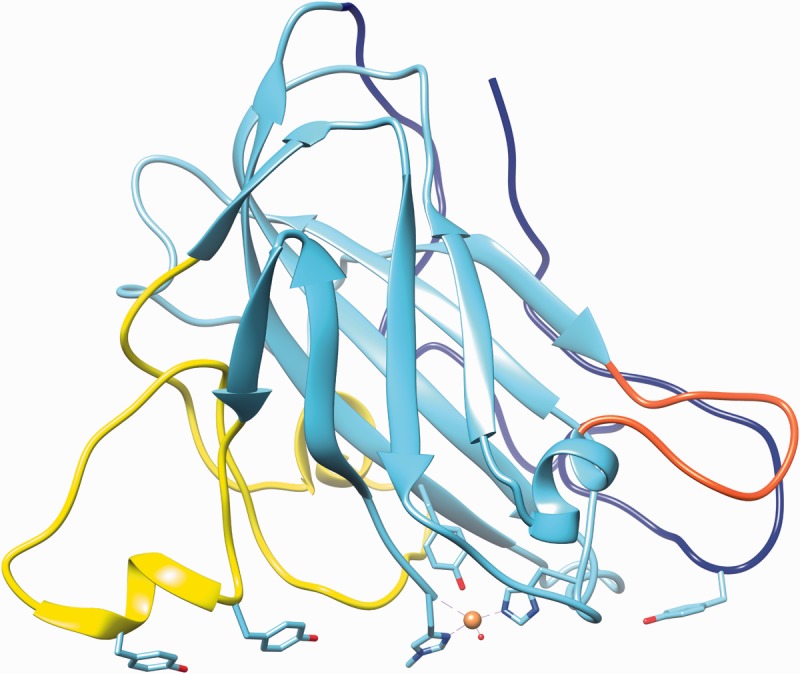

In the next years, five more AA9 structures were resolved [10, 13, 14, 47], and five more AA10 structures have been published [17, 19, 24, 26]. The structure of Neurospora crassa Q7SA1 is representative of AA9 enzymes (Figure 1). The LPMOs with solved structures are all single domain proteins, with the exception of an unusual Vibrio cholerae protein that contains three uncharacterized domains with similarities to cell wall and chitin-binding domains in addition to the AA10 domain [26]. Approximately 20% of the fungal AA9 proteins have a C-terminal cellulose-binding motif CBM1 [14]. Furthermore, the fungal chitin-binding domain CBM18 and uncharacterized domains with similarity to carbohydrate-binding domains are present in some LPMO proteins [27].

Figure 1:

Representative AA9 LPMO from N. crassa selected for lowest average RMSD value among Protein Data Bank models. The structure shown is Q7SA19 [47], and the highlighted loops and residues also incorporate information from [10]. Highlighted in yellow, blue and red are the loops L2, the C-terminal and the short loop, respectively. The copper atom is shown as a sphere with the coordinating residues (two histidines) and the axial tyrosine in stick representation. The three tyrosines of loops L2 and the C-terminal loop, presumed to interact with cellulose substrate, are also indicated in stick representation. The image was created using PDB entry 4EIS with the UCSF Chimera package developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco [48]. (A colour version of this figure is available online at: http://bfg.oxfordjournals.org)

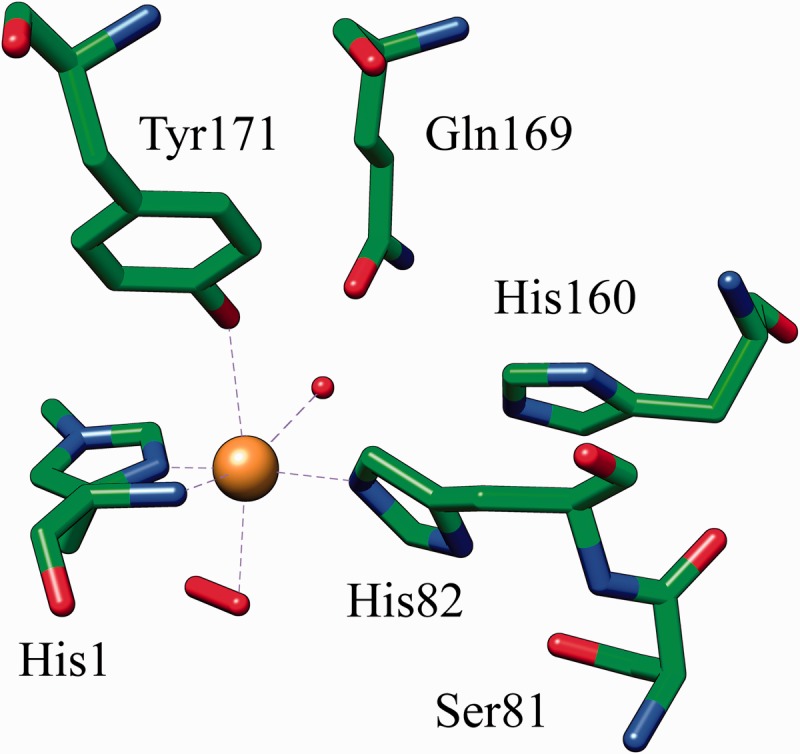

Residues previously presumed to play a role in catalysis are buried inside the structures, and no tunnel, cleft or binding pocket typical of glycoside hydrolases is present. Instead, a planar surface with several aromatic and polar residues that form a CBM1-like cellulose-binding patch are a characteristic feature of LPMOs [14]. Furthermore, LPMOs share a conserved copper ion-binding site that is solvent exposed on the planar surface [13]. Copper is ligated by a ‘histidine brace’ formed by two conserved histidine residues; a conserved tyrosine residue and water molecules further participate in the type II copper hexacoordination in the fungal AA9 LPMOs resulting in an overall octahedral coordination geometry with Jahn–Teller distortion [13, 14] (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

The histidine brace in N. crassa Q7SA19 (PDB ID: 4EIS). Six amino-acids surrounding the metal-binding site are shown in stick representation. Copper is shown as a sphere. Octahedral copper coordination is indicated by dashed lines. The solvent exposed axial ligand is modeled as a hydrogen peroxide (stick) and the fourth equatorial ligand is water (sphere).

An unusual posttranslational modification, methylation of the N-terminal histidine at the imidazole Nε, seems to be present in all AA9 enzymes but is absent from family AA10 LPMOs. Although it has been hypothesized that this modification might influence LPMO reactivity, confirmation of any functional significance is still lacking. The histidine methylation is carried out only in filamentous fungi. The AA9 produced heterologously in yeast lacks the histidine methylation, and yet, it is apparently fully functional [10]. The slight reduction in activation energy reported by Kim et al. [49] for proteins carrying the modification, based on discrete Fourier transform calculations and the assumption of an oxyl radical rather than a superoxyl radical, may or may not be biologically relevant.

Structural differences observed among the different AA9 LPMOs relate to three variable loop regions involved in forming the extended flat substrate-binding surface (Figure 1). The highest variability is seen in the region between strands S1 and S3 known as the L2 loop region, which is much longer in some forms (N. crassa, Q7SA19, NcrPMO-3; Thermoascus aurantiacus, G3XAP7, TaGH61A; T. reesei, Q7Z9M7, HjeGH61B) than in others (N. crassa, Q1K8B6, NcrPMO-2; Thielavia terrestris, G2RGE5, TteGH61E; Phanerochaete chrysosporium, H1AE14, PchGH61D) [10]. A semi-conserved tyrosine residue implicated in substrate binding is part of this loop in those proteins with an extended L2 loop. Two shorter loops closer to the C-terminal end are less variable. Molecular dynamics simulations suggest that far more residues than just the CBM type A-mimicking tyrosine residues are involved in interactions with cellulose, some of which are part of the two fairly flexible shorter loops [13]. Although one might intuitively assume that AA9 enzymes interact with the substrate along the cellulose fibrils and not perpendicular to them, the orientation is still unknown and has been modeled either way [10, 47].

FUNCTION

The 3D structure of an AA9 LPMO confirmed the unlikeliness that these proteins function as conventional endoglucanases. Furthermore, hydrolytic activity was found to be negligible in a careful and thorough study of two AA9 proteins from T. terrestris, ThiteGH61B and ThiteGH61E, using 16 different substrates: no significant amounts of reducing sugars were produced above background levels [14]. However, these and other GH61 proteins were clearly shown to be capable of enhancing cellulose degradation when acting in synergy with the canonical T. reesei cellulases on dilute-acid pretreated corn stover, steam-exploded wheat and rice straw and organosolv-pulped lodgepole pine, but not on relatively pure cellulosic substrates such as Avicel, carboxymethylcellulose or phosphoric acid swollen cellulose without addition of external reductants [14]. It has recently been demonstrated that the synergism between LPMOs and canonical cellulases depends to a large extent on the substrate, specifically on the accessibility of crystalline cellulose and the type of cellulose [50].

The next important step toward the elucidation of AA9 LPMO function actually came from work done on the bacterial counterpart, the AA10 (CBM33) enzyme. Vaaje-Kolstad et al. [22] demonstrated that the CBM33 from S. marcescens possesses catalytic activity that is dependent on molecular oxygen, bivalent cations, addition of reductants and the presence of crystalline substrate, i.e. chito-oligomers with a DP>6. The enzyme alone degrades chitin in an endo-type fashion under these conditions, albeit not completely. However, if a conventional chitinase is added to the mixture, the AA10 enzyme performs a boosting function, leading to an overall increase in chitinolytic activity.

Similar observations were subsequently reported for the fungal AA9 enzymes. Under appropriate conditions, these proteins were shown to perform oxidative cleavage of the crystalline parts of cellulose, releasing mostly oxidized, and to a much lesser extent, native cello-oligosaccharides obtained by activity of C1 oxidizing enzymes close to the reducing chain ends [11]. However, in contrast to the AA10 enzymes characterized so far, which are active on chitin and/or cellulose and mostly oxidize the C1 carbon of glycosidic bonds and release mainly even-numbered products, AA9 enzymes are only active on cellulose, and seem to be more versatile in terms of which carbon atom is oxidized. Release of both even- and odd-numbered cello-oligomers by the same AA9 enzyme has been reported; C1 and C4 oxidized products have been detected in activity assays for different enzymes. More recently, C4 oxidation has been demonstrated by two bacterial cellulolytic AA10 enzymes [24]. In the first papers published, product analysis revealed reducing-end oxidation at C1 leading to an aldonolactone, which undergoes spontaneous ring opening to form aldonic acid, and this seems to be the main activity for AA9 LPMOs [7, 13]. C4 oxidation producing a 4-ketoaldose, that is stable as its ketal, has been subsequently demonstrated for some AA9 enzymes and a few enzymes are capable of oxidizing either at the C1 or C4 position [6, 8]. Whether other AA9s also oxidize at C6 is currently still under debate. C6 oxidation has been claimed for T. aurantiacus TaGH61A (G3XAP7) and Podospora anserina PaGH61B (B2AVF1) based on mass spectrometry results [12, 13]. However, mass spectrometry results alone are not sufficient to establish the identity of the products, and attempts to verify the nature of the non-reducing end oxidation of N. crassa NcrPMO-3 (Q7SA19) by NMR spectroscopy have only confirmed C4 oxidation activity [9]. N. crassa NcrPMO-3 is distinguishable from other AA9 proteins by its ability to efficiently oxidize soluble cello-oligomers from DP5 [9] and its hemicellulolytic activity [51]. It thus remains to be shown whether non-reducing end oxidation is in general limited to 4-ketal formation on the C4 atom participating in the glycosidic bond.

Earlier it was shown that AA9 enzymes depend on a reducing cofactor for activity that is absent in pure cellulose [13]. Several reductants, such as ascorbic acid, reduced glutathione and gallic acid have been used in in vitro studies, and no clear preference of AA9 enzymes for any of these electron donors could be detected [11, 13, 22, 25]. Whether any of these reducing agents are also active in vivo is presently unknown. Gallic acid is a wood component [52], and glutathione and ascorbate can be produced by fungi [53, 54]. They are thus viable candidates as electron donors. Furthermore, noncarbohydrate components of complex substrates, such as lignin, have been suggested to serve as electron donor [55, 56].

In addition to these reductants, cellobiose dehydrogenase (CDH) has also been shown to be competent in this role. CDH is secreted by many white-rot fungi, but only by a few brown-rot species [57]. In gene expression studies, CDHs and AA9s are often co-expressed, suggesting that they may work in unison [58–61]. A clear indication for actual synergism between the enzymes was obtained when it was shown that a combination of T. aurantiacus AA9 and Humicola insolens CDH greatly enhances cellulose degradation by canonical cellulases. Even β-glucosidase alone contributes to cellulose degradation in the presence of AA9 and CDH [15]. Furthermore, a cdh deletion mutant in N. crassa drastically reduces cellulolytic activity compared with wild-type, which could be restored by adding purified Myceliophthora thermophila CDH [7]. In addition, only the combination of heterologously produced AA9 and CDH led to the formation of oxidized products from phosphoric acid swollen cellulose, whereas their production was negligible when only one enzyme was added to the reaction mixture [12].

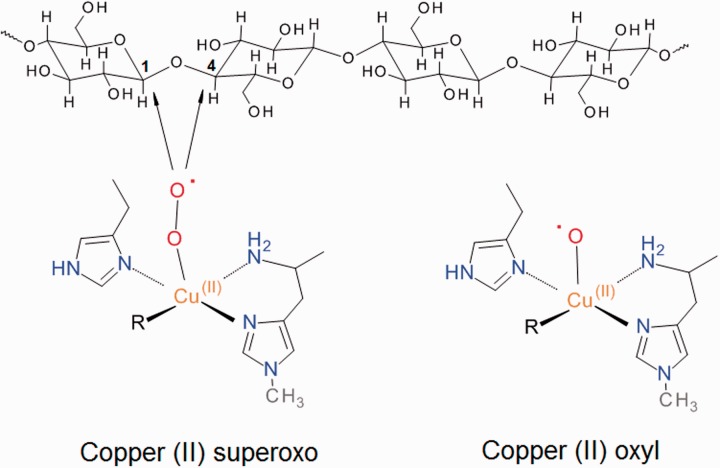

How does CDH support catalytic activity by AA9 LPMOs? It has been proposed that the heme domain of CDH serves as electron donor to reduce the AA9 bound Cu(II) to Cu(I), which then binds O2 similar to copper monooxygenases, and undergoes intramolecular rearrangements to form a copper(II)-superoxo intermediate that attacks the cellulose substrate at the C1 or C4 position [7]. A copper(II)-oxyl radical instead of a copper(II)-superoxo complex has also been suggested for substrate oxygenation [49]; both suggested copper complexes are shown in Figure 3. Kim and colleagues investigated the energetic landscapes for two alternative enzyme-copper radical complexes using density functional theory (DFT) computations. They concluded that the copper(II)-superoxo radical proposed to interact with the substrate has a much higher energy barrier and is thus less likely realized than the alternative, a copper(II)-oxyl radical [49]. Contrary to this conclusion, the recent investigation by Kjaergaard et al. [62], which combines spectroscopic data with DFT calculations, favors a mechanism involving the copper(II)-superoxo radical. As both of these studies model intermediates in the absence of bound polysaccharide, the full mechanism of LPMO is still a matter of speculation.

Figure 3:

Proposed reactive oxygen species generated by LPMO enzymes. The arrows indicate the sites of attack on cellulose observed for different LPMOs.

EVOLUTIONARY ASPECTS

Although much progress has been made in understanding structural and functional properties of LPMOs, there are still many unresolved questions about them. Some of these questions revolve around evolutionary aspects, such as the dramatic gene number expansions in some species [14]. In their seminal paper, Harris and colleagues included a phylogenetic analysis of ∼300 AA9 sequences available at the time, and observed that AA9 LPMOs are widely distributed among the filamentous fungi and largely absent in yeasts [14]. Moreover, they concluded that the AA9 LPMOs must have diversified >600 Myr ago, before the split of Dikarya in ascomycetes and basidiomycetes, as is apparent from the scattered distribution of sequences from these two phyla throughout the phylogenetic tree. This observation is supported by further analyses that include more basidiomycetes representing both white- and brown-rot species [57].

A striking feature of AA9s is the extreme expansion in genes encoding these proteins observed in some genomes, which can reach >30 homologous gene models per species [14, 57, 63]. The reason for this redundancy is still unknown. Harris and colleagues [14] deduced from their phylogenetic analysis that some duplications may be a relatively recent event as exemplified by Coprinopsis cinereus, a fungus with a high species-specific duplication rate. On the other hand, species such as Chaetomium globosum and Parastagonospora nodorum, that are not closely related, have high numbers of AA9-encoding genes which are present throughout the tree, indicating a preponderance of ancient duplications dating back to their common ancestor [14]. The lower numbers of AA9 gene models observed in some fungal groups, such as the Aspergilli, are explained by lineage-specific loss events. An analysis by Floudas et al. [57] focusing more specifically on gene duplication and loss patterns came to different conclusions depending on the methods used. In this study, the authors used the programs CAFÉ [64] and Notung [65, 66] to elucidate duplication/loss patterns for various plant biomass-degrading fungal enzyme families, including AA9 genes. They estimated the AA9 family gene number for the Dikarya node either at 1 or 13 genes, depending on the method used and concluded that ‘the diversification of the [AA9] family predates the separation of Dikarya’ [57]. The results may indicate that an important duplication phase of AA9-encoding genes occurred just at the time of the appearance and early evolution of the Dikarya, ∼650 Myr ago, and is thus intrinsically linked with the appearance of the regularly septated dikaryotic hyphae.

Despite persisting uncertainties regarding the dynamics of the early evolution in the AA9 gene family, some trends are obvious. Among the wood-rot fungi, white-rot fungi have a higher number of AA9-encoding genes than brown-rot fungi because of expansions of AA9 homologs in the former and losses in the latter group [57, 67]. Plant pathogenicity may also be associated with a higher number of AA9 family genes, as suggested in the case of the Dothideomycetes species pair P. nodorum and Mycosphaerella graminicola; the former is the more aggressive pathogen and has 30 genes, whereas the latter houses only two genes for AA9 [68]. However, this may not be a universal trend, as it has been pointed out that among white-rot fungi the basidiomycete phytopathogen Heterobasidion irregulare maintains a lower AA9 gene number than saprothrophic non-pathogenic basidiomycetes [61]. A putative role for AA9 LPMOs in host invasion has been suggested for an AA9 enzyme of the phytopathogen Pyrenochaeta lycopersici, a member of the plant pathogen rich Dothideomycetes, following tomato root infections [69]. Strong induction of P. lycopersici AA9 Plegl1 transcription at 96 h after infection of tomato roots coincides with the switch from biotrophic to necrotrophic fungal growth and hints at a possible role in disease development, which includes tomato root collapse [69, 70].

Most basal fungal groups seem to lack AA9 LPMOs, including Microsporidians [71], Neocallimastigomycota [72], Chytridiomycota [73] and Mucoromycotina [74]. AA9-encoding genes are, with a single exception, also absent in the ascomycetous yeasts (Schizosaccharomycetes and Saccharomycetes), animal pathogens (Onygenales and basidiomycetous yeasts, with the exception of two Cryptococcus species) and, somewhat surprisingly, from the Ustilaginales, a basidiomycete order that includes many plant pathogens [14, 75].

The apparent low functional diversity of AA9s in terms of reactions catalyzed makes it difficult to annotate strongly supported clades in gene trees in terms of functional differences observed among AA9s based on biochemical characterization. Attempts to achieve this have been conducted recently, demonstrating that three major clades distinguish AA9s according to the preferred site of oxidation, with one clade (PMO1) oxidizing the C1, another one (PMO2) the C4 and the third (PMO3) at either the C1 or C4 carbon atom [8]. A different bioinformatic approach was undertaken by Busk and Lange [76] who developed a peptide pattern recognition algorithm to detect and cluster short conserved sequence motifs in protein families and analyzed >750 AA9 proteins. Based on their criteria, AA9 proteins can be divided into 16 subfamilies, of which only six contain characterized members. However, more than one-third of the sequences were too diverged to fall into one of the 16 subfamilies, attesting to a high level of evolutionary rate changes. Interestingly, the few characterized enzymes with demonstrated regioselectivity differences belong to separate subfamilies in this classification also. A recent study gives credence to previous speculations that AA9 proteins might have activity on substrates other than cellulose by demonstrating activity by a specific enzyme from N. crassa (NcLPMO9C) against xyloglucan and 1,3-1,4-β-d-glucan [51]. This discovery, together with the possibility that some LPMOs will be found to be active against other substrates such as xylan, pectin and starch [51, 59] will likely reduce the apparent redundancy and may explain at least partially the AA9 gene expansions in some plant cell wall degrading fungal species.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Recent discoveries in enzymology and biomass degradation research continue to reinforce the view that the hallmark of efficient breakdown of the highly recalcitrant plant cell wall complex is the synergistic activity of many enzymes. Oxidative LPMOs are the most recently recognized players, acting in concert with cellobiose dehydrogenase to introduce strand breaks in cellulose and hemicellulose, thereby enhancing the hydrolytic activity of cellulases and hemicellulases.

That fungi are the only organisms in which all three LPMO families AA9-AA11 can be found is an indication of the importance of LPMOs to these organisms and their lifestyles. The newly described AA11 family has so far been only reported from fungi. Previously, a single fungal AA10 member, a sequence from the Ustilaginomycete S. reilianum, has been recognized by the CAZy database as belonging to this LPMO family [2]. Recent releases of additional genomes from this important phytopathogenic fungal group reveal that this seemingly isolated occurrence of an AA10 gene in the fungi is not because of contamination but is shared by the related genera Ustilago and Pseudozyma in the Ustilaginomycotina [77–83]. However, AA10-encoding genes are absent from the animal pathogens (Malasezziales) in the Ustilaginomycotina [84, 85]. In a previous review, we argued that the sequence similarities between AA9 and AA10 are so low that evolutionary relationship should not be assumed despite striking functional and structural similarities [31]. However, in the light of the recent discoveries of a new LPMO family and a less obvious taxonomic divide between fungal AA9 and bacterial/viral AA10 enzyme families, the evolutionary history including the question of whether there is any homology among the LPMO families should be revisited.

The novel and exciting LPMO discoveries discussed above underline the importance and usefulness of conducting whole genome sequencing efforts even in taxonomic groups that are already represented by a finished genome sequencing project. For comparative purposes, solid coverage of gene families is needed to unravel evolutionary trends that might help direct us toward biological innovations that can contribute to biotechnological breakthroughs, for example, development of cheaper enzymes for biofuels, advancement in the production of commodity and high-value chemicals and further improvement in established biomass degrading applications, such as the food, feed and pulp and paper industries.

Advanced bioinformatics-based evolutionary studies of single LPMO families, and possibly the combined AA9, AA10, and AA11 families, are needed to address remaining open questions about the diversity of these interesting oxidative enzymes. With the ongoing discovery of new classes of LPMOs, it becomes increasingly evident that oxidative biomass degrading enzymes are as important and common as their long-known hydrolytic counterparts.

Key Points.

Structures of known AA9 proteins are strongly conserved but contain three semi-conserved loop regions, which appear to be relevant for substrate binding.

The characterized AA9 proteins have been shown to be oxidative enzymes that generate C1 reducing end, and C4 non-reducing end oxidized products.

Numbers of AA9 encoding genes in fungal genomes varies widely, and they are present in all plant cell wall degrading fungi with the exception of phytopathogenic Ustilaginales, which have acquired instead genes encoding AA10 proteins.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Quy Vo for assistance in preparation of the protein structure illustrations.

Biographies

Ingo Morgenstern is a postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Structural and Functional Genomics at Concordia University. His research is centered around evolutionary aspects of fungal lignocellulose decaying enzymes.

Justin Powlowski is a founding member of Concordia University’s Centre for Structural and Functional Genomics. He has more than 30 years of experience working with enzymes involved in microbial biodegradation pathways.

Adrian Tsang is the director of the Centre for Structural and Functional Genomics at Concordia University. His research focusses on fungal genomics and the production and characterization of biomass-degrading enzymes.

FUNDING

Research on lignocellulose-active proteins at Concordia University is supported by funding from Genome Canada, Génome Québec and the Bioconversion Network of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

References

- 1.Horn SJ, Vaaje-Kolstad G, Westereng B, et al. Novel enzymes for the degradation of cellulose. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lombard V, Golaconda Ramulu H, Drula E, et al. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D490–95. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemsworth GR, Henrissat B, Davies GJ, et al. Discovery and characterization of a new family of lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:122–6. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, et al. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D233–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levasseur A, Drula E, Lombard V, et al. Expansion of the enzymatic repertoire of the CAZy database to integrate auxiliary redox enzymes. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vu VV, Beeson WT, Phillips CM, et al. Determinants of regioselective hydroxylation in the fungal polysaccharide monooxygenases. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:562–5. doi: 10.1021/ja409384b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips CM, Beeson WT, Cate JH, et al. Cellobiose dehydrogenase and a copper-dependent polysaccharide monooxygenase potentiate cellulose degradation by Neurospora crassa. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:1399–406. doi: 10.1021/cb200351y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beeson WT, Phillips CM, Cate JH, et al. Oxidative cleavage of cellulose by fungal copper-dependent polysaccharide monooxygenases. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:890–2. doi: 10.1021/ja210657t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isaksen T, Westereng B, Aachmann FL, et al. A C4-oxidizing lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase cleaving both cellulose and cello- oligosaccharides. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:2632–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.530196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu M, Beckham GT, Larsson AM, et al. Crystal structure and computational characterization of the lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase GH61D from the Basidiomycota fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:12828–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.459396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westereng B, Ishida T, Vaaje-Kolstad G, et al. The putative endoglucanase PcGH61D from Phanerochaete chrysosporium is a metal- dependent oxidative enzyme that cleaves cellulose. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bey M, Zhou S, Poidevin L, et al. Cello-oligosaccharide oxidation reveals differences between two lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (family GH61) from Podospora anserina. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:488–96. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02942-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinlan RJ, Sweeney MD, Lo Leggio L, et al. Insights into the oxidative degradation of cellulose by a copper metalloenzyme that exploits biomass components. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:15079–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105776108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PV, Welner D, McFarland KC, et al. Stimulation of lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysis by proteins of glycoside hydrolase family 61: structure and function of a large, enigmatic family. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3305–16. doi: 10.1021/bi100009p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langston JA, Shaghasi T, Abbate E, et al. Oxidoreductive cellulose depolymerization by the enzymes cellobiose dehydrogenase and glycoside hydrolase 61. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:7007–15. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05815-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karkehabadi S, Hansson H, Kim S, et al. The first structure of a glycoside hydrolase family 61 member, Cel61B from Hypocrea jecorina, at 1.6 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:144–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemsworth GR, Taylor EJ, Kim RQ, et al. The copper active site of CBM33 polysaccharide oxygenases. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:6069–77. doi: 10.1021/ja402106e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forsberg Z, Rohr AK, Mekasha S, et al. Comparative study of two chitin-active and two cellulose-active AA10-type lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Biochemistry. 2014;53:1647–56. doi: 10.1021/bi5000433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaaje-Kolstad G, Bohle LA, Gaseidnes S, et al. Characterization of the chitinolytic machinery of Enterococcus faecalis V583 and high- resolution structure of its oxidative CBM33 enzyme. J Mol Biol. 2012;416:239–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gudmundsson M, Kim S, Wu M, et al. Structural and electronic snapshots during the transition from a Cu(II) to Cu(I) metal center of a lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase by x-ray photoreduction. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:18782–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.563494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaaje-Kolstad G, Houston DR, Riemen AH, et al. Crystal structure and binding properties of the Serratia marcescens chitin-binding protein CBP21. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11313–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaaje-Kolstad G, Westereng B, Horn SJ, et al. An oxidative enzyme boosting the enzymatic conversion of recalcitrant polysaccharides. Science. 2010;330:219–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1192231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aachmann FL, Sorlie M, Skjak-Braek G, et al. NMR structure of a lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase provides insight into copper binding, protein dynamics, and substrate interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:18779–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208822109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forsberg Z, Mackenzie AK, Sorlie M, et al. Structural and functional characterization of a conserved pair of bacterial cellulose-oxidizing lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8446–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402771111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forsberg Z, Vaaje-Kolstad G, Westereng B, et al. Cleavage of cellulose by a CBM33 protein. Protein Sci. 2011;20:1479–83. doi: 10.1002/pro.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong E, Vaaje-Kolstad G, Ghosh A, et al. The Vibrio cholerae colonization factor GbpA possesses a modular structure that governs binding to different host surfaces. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002373. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leggio LL, Welner D, De Maria L. A structural overview of GH61 proteins - fungal cellulose degrading polysaccharide monooxygenases. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2012;2:e201209019. doi: 10.5936/csbj.201209019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris PV, Xu F, Kreel NE, et al. New enzyme insights drive advances in commercial ethanol production. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014;19:162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimarogona M, Topakas E, Christakopoulos P. Recalcitrant polysaccharide degradation by novel oxidative biocatalysts. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:8455–65. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5197-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemsworth GR, Davies GJ, Walton PH. Recent insights into copper-containing lytic polysaccharide mono-oxygenases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:660–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekwe E, Morgenstern I, Tsang A, et al. Non-hydrolytic cellulose active proteins: Research progress and potential application in biorefineries. Ind Biotechnol. 2013;9:123–31. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klemm D, Heublein B, Fink HP, et al. Cellulose: fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:3358–93. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Himmel ME, Ding SY, Johnson DK, et al. Biomass recalcitrance: engineering plants and enzymes for biofuels production. Science. 2007;315:804–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1137016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merino ST, Cherry J. Progress and challenges in enzyme development for biomass utilization. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2007;108:95–120. doi: 10.1007/10_2007_066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cannella D, Hsieh CWC, Felby C, et al. Production and effect of aldonic acids during enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose at high dry matter content. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eriksson K-E, Blanchette RA, Ander P. Microbial and Enzymatic Degradation of Wood and Wood Components. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reese ET, Siu RG, Levinson HS. The biological degradation of soluble cellulose derivatives and its relationship to the mechanism of cellulose hydrolysis. J Bacteriol. 1950;59:485–97. doi: 10.1128/jb.59.4.485-497.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levinson HS, Reese ET. Enzymatic hydrolysis of soluble cellulose derivatives as measured by changes in viscosity. J Gen Physiol. 1950;33:601–28. doi: 10.1085/jgp.33.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reese ET. A microbiological process report; enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose. Appl Microbiol. 1956;4:39–45. doi: 10.1128/am.4.1.39-45.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eriksson KE, Pettersson B, Westermark U. Oxidation: an important enzyme reaction in fungal degradation of cellulose. FEBS Lett. 1974;49:282–5. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(74)80531-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saloheimo M, Nakari-Setala T, Tenkanen M, et al. cDNA cloning of a Trichoderma reesei cellulase and demonstration of endoglucanase activity by expression in yeast. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:584–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karlsson J, Saloheimo M, Siika-Aho M, et al. Homologous expression and characterization of Cel61A (EG IV) of Trichoderma reesei. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:6498–507. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hara Y, Hinoki Y, Shimoi H, et al. Cloning and sequence analysis of endoglucanase genes from an industrial fungus, Aspergillus kawachii. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:2010–13. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bauer S, Vasu P, Persson S, et al. Development and application of a suite of polysaccharide-degrading enzymes for analyzing plant cell walls. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11417–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604632103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koseki T, Mese Y, Fushinobu S, et al. Biochemical characterization of a glycoside hydrolase family 61 endoglucanase from Aspergillus kawachii. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;77:1279–85. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armesilla AL, Thurston CF, Yague E. CEL1: a novel cellulose binding protein secreted by Agaricus bisporus during growth on crystalline cellulose. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;116:293–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li X, Beeson WT, Phillips CM, et al. Structural basis for substrate targeting and catalysis by fungal polysaccharide monooxygenases. Structure. 2012;20:1051–61. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–12. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim S, Stahlberg J, Sandgren M, et al. Quantum mechanical calculations suggest that lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases use a copper- oxyl, oxygen-rebound mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:149–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316609111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu J, Arantes V, Pribowo A, et al. Substrate factors that influence the synergistic interaction of AA9 and cellulases during the enzymatic hydrolysis of biomass. Energy Environ Sci. 2014;7:2308–15. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agger JW, Isaksen T, Varnai A, et al. Discovery of LPMO activity on hemicelluloses shows the importance of oxidative processes in plant cell wall degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:6287–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323629111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laks PE, Hemingway RW. Plant polyphenols-synthesis, properties, significance - concluding remarks. Plant Polyphenol Synth Propert Signif. 1992;59:1035–6. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petrescu S, Hulea SA, Stan R, et al. A Yeast-strain that uses d-galacturonic acid as a substrate for l-ascorbic-acid biosynthesis. Biotechnol Lett. 1992;14:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pocsi I, Prade RA, Penninckx MJ. Glutathione, altruistic metabolite in fungi. Adv Microbial Physiol. 2004;49:1–76. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(04)49001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dimarogona M, Topakas E, Olsson L, et al. Lignin boosts the cellulase performance of a GH-61 enzyme from Sporotrichum thermophile. Bioresour Technol. 2012;110:480–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.01.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cannella D, Hsieh CW, Felby C, et al. Production and effect of aldonic acids during enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose at high dry matter content. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Floudas D, Binder M, Riley R, et al. The Paleozoic origin of enzymatic lignin decomposition reconstructed from 31 fungal genomes. Science. 2012;336:1715–19. doi: 10.1126/science.1221748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wymelenberg AV, Gaskell J, Mozuch M, et al. Comparative transcriptome and secretome analysis of wood decay fungi postia placenta and phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3599–610. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00058-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hori C, Igarashi K, Katayama A, et al. Effects of xylan and starch on secretome of the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium grown on cellulose. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;321:14–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Longoni P, Rodolfi M, Pantaleoni L, et al. Functional analysis of the degradation of cellulosic substrates by a Chaetomium globosum endophytic isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:3693–705. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00124-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yakovlev I, Vaaje-Kolstad G, Hietala AM, et al. Substrate-specific transcription of the enigmatic GH61 family of the pathogenic white-rot fungus Heterobasidion irregulare during growth on lignocellulose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;95:979–90. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4206-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kjaergaard CH, Qayyum MF, Wong SD, et al. Spectroscopic and computational insight into the activation of O2 by the mononuclear Cu center in polysaccharide monooxygenases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8797–802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408115111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berka RM, Grigoriev IV, Otillar R, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of the thermophilic biomass-degrading fungi Myceliophthora thermophila and Thielavia terrestris. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:922–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth JP, et al. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1269–71. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vernot B, Stolzer M, Goldman A, et al. Reconciliation with non-binary species trees. J Comput Biol. 2008;15:981–1006. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2008.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Durand D, Halldorsson BV, Vernot B. A hybrid micro-macroevolutionary approach to gene tree reconstruction. J Comput Biol. 2006;13:320–35. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2006.13.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hori C, Gaskell J, Igarashi K, et al. Genomewide analysis of polysaccharides degrading enzymes in 11 white- and brown-rot Polyporales provides insight into mechanisms of wood decay. Mycologia. 2013;105:1412–27. doi: 10.3852/13-072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ipcho SV, Hane JK, Antoni EA, et al. Transcriptome analysis of Stagonospora nodorum: gene models, effectors, metabolism and pantothenate dispensability. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;13:531–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Valente MT, Infantino A, Aragona M. Molecular and functional characterization of an endoglucanase in the phytopathogenic fungus Pyrenochaeta lycopersici. Curr Genet. 2011;57:241–51. doi: 10.1007/s00294-011-0343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goodenough P, Kempton R. The activity of cell-wall degrading enzymes in tomato roots infected with Pyrenochaeta lycopersici and the effect of sugar concentrations in these roots on disease development. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1976;9:313–20. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pan G, Xu J, Li T, et al. Comparative genomics of parasitic silkworm microsporidia reveal an association between genome expansion and host adaptation. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Youssef NH, Couger MB, Struchtemeyer CG, et al. The genome of the anaerobic fungus Orpinomyces sp. strain C1A reveals the unique evolutionary history of a remarkable plant biomass degrader. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:4620–34. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00821-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Joneson S, Stajich JE, Shiu SH, et al. Genomic transition to pathogenicity in chytrid fungi. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002338. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ma LJ, Ibrahim AS, Skory C, et al. Genomic analysis of the basal lineage fungus Rhizopus oryzae reveals a whole-genome duplication. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Žifčáková L, Baldrian P. Fungal polysaccharide monooxygenases: new players in the decomposition of cellulose. Fungal Ecol. 2012;5:481–9. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Busk PK, Lange L. Function-based classification of carbohydrate-active enzymes by recognition of short, conserved peptide motifs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:3380–91. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03803-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schirawski J, Mannhaupt G, Munch K, et al. Pathogenicity determinants in smut fungi revealed by genome comparison. Science. 2010;330:1546–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1195330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morita T, Koike H, Koyama Y, et al. Genome sequence of the basidiomycetous yeast Pseudozyma antarctica T-34, a producer of the glycolipid biosurfactants mannosylerythritol lipids. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e0006413. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00064-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Konishi M, Hatada Y, Horiuchi J. Draft genome sequence of the basidiomycetous yeast-like fungus Pseudozyma hubeiensis SY62, which produces an abundant amount of the biosurfactant mannosylerythritol lipids. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00409–13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00409-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oliveira JV, Dos Santos RA, Borges TA, et al. Draft genome sequence of Pseudozyma brasiliensis sp. nov. Strain GHG001, a high producer of endo-1,4-xylanase isolated from an insect pest of sugarcane. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00920–13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00920-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lorenz S, Guenther M, Grumaz C, et al. Genome sequence of the basidiomycetous fungus Pseudozyma aphidis DSM70725, an efficient producer of biosurfactant mannosylerythritol lipids. Genome Announc. 2014;2:e00053–14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00053-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Laurie JD, Ali S, Linning R, et al. Genome comparison of barley and maize smut fungi reveals targeted loss of RNA silencing components and species-specific presence of transposable elements. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1733–45. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.097261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kamper J, Kahmann R, Bolker M, et al. Insights from the genome of the biotrophic fungal plant pathogen Ustilago maydis. Nature. 2006;444:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature05248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xu J, Saunders CW, Hu P, et al. Dandruff-associated Malassezia genomes reveal convergent and divergent virulence traits shared with plant and human fungal pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18730–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706756104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gioti A, Nystedt B, Li W, et al. Genomic insights into the atopic eczema-associated skin commensal yeast Malassezia sympodialis. Mbio. 2013;4:e00572–00512. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00572-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]