Abstract

Objective

To study whether neonatal and infant mortality, after adjustments for differences in case mix, were independent of the type of hospital in which the delivery was carried out.

Data

The Medical Birth Registry of Norway provided detailed medical information for all births in Norway.

Study Design

Hospitals were classified into two groups: local hospitals/maternity clinics versus central/regional hospitals. Outcomes were neonatal and infant mortality. The data were analyzed using propensity score weighting to make adjustments for differences in case mix between the two groups of hospitals. This analysis was supplemented with analyses of 13 local hospitals that were closed. Using a difference-in-difference approach, the effects that these closures had on neonatal and infant mortality were estimated.

Principal Finding

Neonatal and infant mortality were not affected by the type of hospital where the delivery took place.

Conclusion

A regionalized maternity service does not lead to increased neonatal and infant mortality. This is mainly because high-risk deliveries were identified well in advance of the birth, and referred to a larger hospital with sufficient perinatal resources to deal with these deliveries.

Keywords: Program evaluation, risk adjustment for clinical outcomes, determinants of health, obstetrics/gynecology

Specialized medicine has become a strong impetus for hospital centralization. Use of specialized medical expertise and advanced technology are extremely costly. Health care professionals and politicians claim that all patients should have access to the best services available. Consequently, centralization is required to ensure that hospitals serve sufficiently large patient populations. At the same time, closure of local hospitals is highly contentious. All over the world, plans for restructuring trigger vigorous protests from local patient organizations, hospital employees, and community action groups. Few policy issues are more politically sensitive than proposals to shut down local maternity units.

The crux of the matter is whether prospective mothers and their infants benefit from hospital centralization. We investigated this research question using maternity care in Norway. In Norway, maternity care is decentralized. Low-risk deliveries are carried out at local hospitals (level I units), while high-risk deliveries are referred to central or regional hospitals with neonatal departments (level II and III units). The question we raise is whether neonatal and infant mortality, after adjustments for differences in case mix, are independent of the type of hospital in which the delivery is carried out.

The challenge with this type of study is to control for the fact that central/regional hospitals have a higher proportion of mothers and infants with risk factors compared with local hospitals. Our data contained a large number of variables about the health status of the mother and child. This made it possible to make proper adjustments for differences in case mix between hospitals by using propensity score weighting. We also carried out an analysis of the local hospitals that were closed down from 1979 and onward. Here, we used a difference-in-difference approach to study whether these closures had an influence on neonatal and infant mortality.

Below we first describe the background for the study—among other things the effect that a decentralized maternity service may have on neonatal and infant mortality. We describe the way maternity and perinatal services in Norway are organized. We then describe the data and our two main analyses—the propensity score weighting and the difference-in-difference approach to the study of local hospital closure. Finally, we describe and discuss our results.

Background—Decentralization of Maternity Services

High-risk infants have better health outcomes in hospitals with neonatal departments—typically located at central or regional hospitals (level II and level III units). In a review encompassing 41 publications, including randomized clinically controlled trails, cohort, and case-control studies published between 1979 and 2008, Lasswell et al. (2010) conclude: “for VLBW (birthweight <1,500 g) and VPT (less than 32 weeks' gestation) infants, birth outside of a level III hospital is significantly associated with increased likelihood of neonatal or predischarge death.” Seen in isolation, this could indicate that centralization of deliveries to large units is beneficial.

However, it can be argued that local maternity units should be kept open if there are appropriate and effective referral routines for high-risk deliveries to central or regional hospitals. One condition is that high-risk deliveries can be identified well in advance of the birth. With effective screening and good routines for referral, small local maternity units can then provide a service for low-risk deliveries. This gives mothers with low-risk pregnancies the possibility to give birth in their own local communities, without having to travel great distances to a central or a regional hospital. Traditionally, this has also been the reasoning behind organization of maternity care in several countries (Hein 2004; Yu and Dunn 2004; Zeitlin, Papiernik, and Bréart 2004).

In the 1970s, the concept of regionalization of perinatal care was introduced in the United States (Berger, Gillings, and Siegel 1976). Hospitals were classified into three levels of care in relation to the services they could provide for high-risk mothers and babies (Committee on Perinatal Health 1976). Guidelines for referral and transport systems were set up between the different levels. At the end of the previous century, perinatal care was regionalized in about 30 states (Shaffer 2001).

Several western European countries have decentralized maternity services that ensure good access independent of place of residence, while at the same time ensuring safe care for mothers and infants by selection of mothers according to risk (Yu and Dunn 2004). For example, in Norway the overall aim for maternity care is that women shall have access to decentralized maternity services of a high professional standard at each maternity unit (Ministry of Health and Care Services 2009). As a general rule, mothers shall give birth at the maternity unit they belong to, according to the hospital's catchment area. There is little competition between hospitals for women giving birth. The country is divided into hospital areas in which the capacity of maternity units is planned according to the expected number of births within the catchment area.

High-risk mothers who live in the catchment area of a local hospital or a maternity clinic shall be referred to central or regional hospitals which have their own neonatal department for dealing with high-risk deliveries. These mothers are identified at antenatal check-ups in good time before the expected date of delivery. Deliveries are identified as high-risk deliveries on the basis of medical criteria, developed by the Norwegian Directorate of Health (Norwegian Directorate of Health 2010; Grytten, Monkerud, and Sørensen 2012). From week 9 in the pregnancy until the expected date of delivery, mothers have seven antenatal check-ups, which are free, with a health visitor and a doctor (Norwegian Directorate of Health and Social Affairs 2005). All hospitals, where nearly all deliveries take place, are publically owned and financed, with obstetricians who receive a fixed salary. Everyone has free health care at the point of delivery (Ministry of Health 2002; Grytten, Skau, and Sørensen 2011).

There are few well-designed studies where the effect of decentralized maternity care on infant health outcomes has been evaluated. Most of the existing studies have been carried out using high-risk deliveries (for a review see Lasswell et al. 2010). There are few studies that have investigated which is the safest place for women with a low-risk pregnancy to give birth, and the studies that have been carried out show conflicting results. Some show that it is safer, or just as safe, for low-risk mothers to give birth in a small hospital as in a large hospital (Hemminki 1985; Rosenblatt, Reinken, and Shoemack 1985; Paneth et al. 1987; Lumley 1988; Mayfield et al. 1990; LeFevre et al. 1992; Viisainen, Gissler, and Hemminki 1994; Cole and Macfarlane 1995; Tracy et al. 2006). A few studies show the opposite (Albers and Savitz 1991; Moster, Lie, and Markestad 1999; Heller et al. 2002). Most research within this area is based on small samples within a limited period of time, and where the samples are not necessarily representative of the population of mothers who give birth. Typically, they have often been carried out in a small geographical area with few hospitals.

A basic problem with many of the studies is that hospital level is not well defined, and often insufficiently reported (Blackmon, Barfield, and Stark 2009). Hospitals are most often grouped according to the number of births—for example, <100, 100–200, and so on. However, this classification may not reflect the level of perinatal resources of the hospitals. This makes comparisons between studies difficult. This also creates doubt about whether differences between hospitals in infant health outcomes are related to differences in perinatal resources or not.

Material and Methods

The Source of the Data and Key Variables

The analyses were carried out on data from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway (MBRN) (http://www.fhi.no). All maternity units are required to report all births to MBRN (Irgens 2000).

Outcomes were measured as neonatal mortality (the infant died within the first month after birth) and infant mortality (died within the first year after birth). Hospitals were classified into two groups: those with their own neonatal department for dealing with high-risk deliveries (central and regional hospitals), and those that did not have their own neonatal department (local hospitals and maternity clinics).1 This classification also reflects differences in obstetric competence between the hospitals. Throughout the whole study period the number of hospitals with their own neonatal department was 22. The number of local hospitals fell from 43 in 1979 to 26 in 2005. Less than 1 percent of all deliveries are carried out in maternity clinics. During the period 1980–1994, the number of maternity clinics fell from 30 to 10 (Schmidt et al. 1997; Nilsen, Daltveit, and Irgens 2001).

Propensity Score Weighting

Following Angrist and Pischke (2009), we adjust for differences in case mix between local hospitals/maternity clinics versus central/regional hospitals by using propensity score weighting. Propensity score weighting is done by weighting up subjects that have a relatively low probability of receiving treatment, and by weighting down subjects that have a relatively high probability of receiving treatment (Hirano 2001; Kurth et al. 2006; Leslie and Thiebaud 2007; Harder, Stuart, and Anthony 2010). These weights are then used in a subsequent regression analysis with treatment status (central/regional hospitals vs local hospitals/maternity clinics) as the explanatory variable. With successful weighting the two groups of hospitals should not differ in any systematic way with respect to observed risk factors. In that way, weighting should assure that any potential bias from a selection of mothers into one particular type of hospital is adjusted for (Robins, Hernán, and Brumback 2000; Hirano, Imbens, and Ridder 2003).

Propensity score weighting proceeds in two steps. First, for each year we estimated the probability of delivery in a central or regional hospital (CR = 1) by way of a binary logistic (logit) regression:

| (1) |

such that we obtained the estimated probability of delivery at a central or regional hospital of

| (2) |

We then computed the inverse probability of treatment weight for each individual delivery (Hirano 2001; Kurth et al. 2006; Leslie and Thiebaud 2007; Harder, Stuart, and Anthony 2010):

| (3) |

where P is the probability of delivery in the actual place of delivery if the mother gives birth in a central or regional hospital and 1 − P is the probability of delivery in the actual place of delivery if the mother gives birth in a local hospital or maternity clinic. The factors in square brackets ensure that the weights in treatment groups (CR = 1, CR = 0) sum to the actual number of observations (i.e., to nCR=1 and nCR=0 respectively).

In the second step of the analysis we estimated the relationship:

| (4) |

in a weighted logistic regression using w as weight. For comparison, we also estimated the unweighted version of Equation (4).

The following risk factors were used: mother's age, immigrant status, level of education, marital status, and predisposing medical factors (asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, heart disease, chronic hypertension, chronic kidney failure, rheumatoid arthritis, preeclampsia, bleeding during pregnancy) and characteristics of the birth (birthweight, gestation length, abnormal presentation, single baby birth, previous Caesarean section, infant boy).

Local Hospital Closures—The Difference-in-Difference Analyses

During the period 1979–2005, altogether 17 maternity wards in local hospitals were closed down. For 13 of these wards, the catchment area after closure belonged to a central/regional hospital.2 The question is whether infant health outcomes improved after the closure. If this was the case, this indicates that too few high-risk deliveries were referred to central/regional hospitals before closure. We specified the following equation:

| (5) |

Equation (5) expresses a basic difference-in-difference design with two groups and two periods (Woolridge 2002). The first group, the treatment group, contained births in the catchment areas that were affected by the hospital closure (Closure = 1). The second group, the control group, contained births in the catchment areas for all the local hospitals that were not closed down (Closure = 0). We defined a preclosure period and a postclosure period. Each period was limited to 5 years before closure (Period = 0) and to 5 years after closure (Period = 1). For each catchment area that was affected by a hospital closure, we estimated two separate models: one in which neonatal mortality (=1) was the dependent variable, and one in which infant mortality (=1) was the dependent variable. All variables in Equation (5) are discrete; hence, a linear probability model can be used for the estimation (Angrist 2001).

The coefficient β2 represents the trend effect. This is a change in infant health outcomes that would have happened without the closure. This effect was estimated for the local hospitals that were not closed down. The coefficient β3 measures the effect of hospital closure on infant health outcomes. This was done by comparing the difference in infant health after and before the closure for hospitals that were affected by the closure, to the same difference for hospitals that were not affected. We expect a negative sign of β3 if infant health outcomes improved after the closure. The coefficient β3 was adjusted for the fact that the two groups of hospitals could have had a different level of infant health outcomes before the closure. This last effect was measured by the coefficient β1. We included all risk factors that measure the characteristics of the health status of the mother and the child into Equation (5). In this way, we controlled for observed differences in risk factors between the control group and the treatment group.

Study Population

Our main analyses were done for all deliveries, that is, the samples included both low- and high-risk deliveries. In addition, in the propensity score weighting, we carried out analyses on a subsample that contained high-risk deliveries only. The subsample was limited to babies with a birthweight of 2,500 g or less.3 Low birthweight is one of the risk factor that contributes most to infant mortality and poor health outcomes later in life (McCormick 1985). The hospital closure analysis was done for all deliveries, and separately for each hospital. There were not enough high-risk births in these hospitals to carry out a separate analysis for these.

Results

The Distribution of Deliveries According to Type of Hospital

Throughout the whole period 1980 to 2005, there were nearly 1.5 million deliveries in Norway (Table 1). About 75 percent of these were in central or regional hospitals, and the rest in local hospitals or maternity clinics. There was a marked fall in the percentage of deliveries in local hospitals and maternity clinics, from 35.2 percent in 1980 to 19.5 percent in 2005. This reduction was offset by a corresponding increase in the number of deliveries in central and regional hospitals.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics. Percentage of Deliveries According to Type of Hospital and Year

| All Deliveries |

Deliveries with Birthweight ≤2,500 g |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Central/Regional Hospitals (%) | Local Hospitals/Maternity Clinics (%) | Total (N) | Central/Regional Hospitals (%) | Local Hospitals/Maternity Clinics (%) | Total (N) |

| 1980 | 64.8 | 35.2 | 50,915 | 77.1 | 22.9 | 2,098 |

| 1981 | 66.0 | 34.0 | 50,564 | 77.5 | 22.5 | 2,148 |

| 1982 | 67.3 | 32.7 | 51,133 | 77.4 | 22.6 | 2,167 |

| 1983 | 67.9 | 32.1 | 49,780 | 80.2 | 19.8 | 2,240 |

| 1984 | 67.7 | 32.3 | 50,134 | 81.1 | 18.9 | 2,263 |

| 1985 | 70.0 | 30.0 | 51,002 | 81.4 | 18.6 | 2,407 |

| 1986 | 71.5 | 28.5 | 52,469 | 81.8 | 18.2 | 2,426 |

| 1987 | 72.5 | 27.5 | 53,949 | 84.4 | 15.6 | 2,585 |

| 1988 | 73.8 | 26.2 | 57,519 | 87.3 | 12.7 | 2,745 |

| 1989 | 75.3 | 24.7 | 59,257 | 87.6 | 12.4 | 2,843 |

| 1990 | 75.3 | 24.7 | 61,069 | 81.5 | 18.5 | 3,149 |

| 1991 | 75.1 | 24.9 | 60,936 | 82.5 | 17.5 | 3,251 |

| 1992 | 75.4 | 24.6 | 60,211 | 83.0 | 17.0 | 3,072 |

| 1993 | 75.7 | 24.3 | 59,766 | 84.5 | 15.5 | 2,973 |

| 1994 | 75.7 | 24.3 | 59,830 | 89.7 | 10.3 | 2,984 |

| 1995 | 75.5 | 24.5 | 59,808 | 89.6 | 10.4 | 2,881 |

| 1996 | 76.4 | 23.6 | 60,432 | 90.4 | 9.6 | 2,910 |

| 1997 | 76.5 | 23.5 | 59,266 | 91.4 | 8.6 | 2,853 |

| 1998 | 76.4 | 23.6 | 57,776 | 90.1 | 9.9 | 2,786 |

| 1999 | 77.9 | 22.1 | 59,421 | 90.8 | 9.2 | 3,073 |

| 2000 | 78.4 | 21.6 | 59,382 | 92.0 | 8.0 | 3,095 |

| 2001 | 78.9 | 21.1 | 56,841 | 91.8 | 8.2 | 2,995 |

| 2002 | 79.1 | 20.9 | 55,912 | 92.8 | 7.2 | 2,938 |

| 2003 | 79.2 | 20.8 | 57,111 | 92.7 | 7.3 | 2,960 |

| 2004 | 79.2 | 20.8 | 57,493 | 92.7 | 7.3 | 2,922 |

| 2005 | 80.5 | 19.5 | 56,421 | 93.4 | 6.6 | 2,915 |

Throughout the period 1980–2005, 4.9 percent of babies had a birthweight of 2,500 g or less. At the beginning of the 1980s, nearly 25 percent of these deliveries took place in local hospitals or maternity clinics. This percentage fell to less than 10 percent from 1996 and onwards. This is less than 300 deliveries per year for all the local hospitals in our study. At that time well over 90 percent of all deliveries of babies with a low birthweight took place in central or regional hospitals.

The Distribution of Risk Factors According to Type of Hospital before and after Weighting

A simple check for whether the propensity score weighting was successful is to look at differences in case mix before and after weighting for each group of hospital. Appendix 1 shows weighted and nonweighted results for the year 1990.

On many counts, characteristics of the mothers and of the birth were different between the central/regional hospitals and the local hospitals/maternity clinics before weighting. For example, central/regional hospitals had more than twice as many deliveries by nonwestern immigrant mothers than did local hospitals/maternity clinics. The difference was highly significant in a chi-square test (p < .001). Moreover, unadjusted differences between the hospitals with respect to predisposing factors of the mother and characteristics of the birth were statistically significant for most factors (p < .05 for 8 out of 15 predisposing factors and characteristics of the birth).

The propensity score weighting effectively and substantially leveled out the case mix differences between the two groups of hospital (p > .05). For instance, adjusted proportions of deliveries by nonwestern immigrant mothers were in practical terms the same in both groups. This was also the case for all the other risk factors after the adjustments. The same pattern was evident for the analogous analyses for the remaining years in the period of study (not reported).

Infant Health Outcomes According to Type of Hospital—Propensity Score Weighting

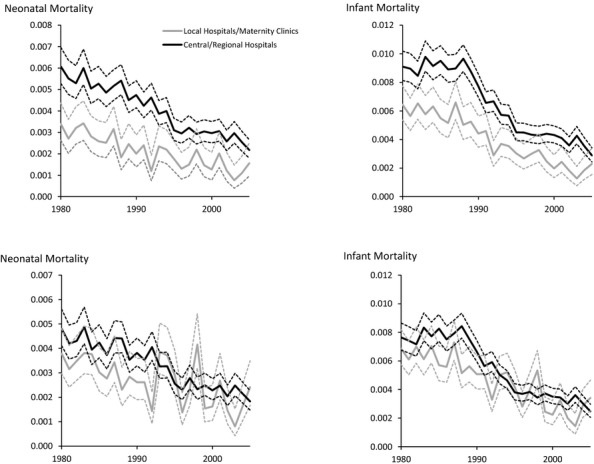

In the analyses of all deliveries without adjustments for risk factors, both neonatal and infant mortality were higher in central/regional hospitals than in local hospitals/maternity clinics for most of the years (Figure1 top). For example, the 95 percent confidence interval for the probability of dying within 1 month after birth did not overlap between the two types of hospitals for 21 of the 26 years (Appendix 2). For both types of hospital, there was a marked reduction in both neonatal and infant mortality from 1980 to 2005 (Figure1).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted (Top) and Adjusted (Bottom) Effects of Type of Hospital on Neonatal and Infant Mortality According to Year.Notes. All deliveries 1980–2005. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are given by dotted lines.

There was no statistically significant difference in neonatal mortality between the two types of hospital for 22 of the 26 years after adjusting for risk factors (Figure1 bottom and Appendix 2). For 3 of the 4 years where the confidence intervals did not overlap (1988, 1992, and 2003), the neonatal mortality was lower in local hospitals/maternity clinics compared with central/regional hospitals.

For infant mortality the confidence intervals overlapped for 21 of the 26 years after the adjustments (Appendix 3). For 4 of the 5 years where the confidence intervals did not overlap (1985, 1988, 1992, and 2003), infant mortality was lower in local hospitals/maternity clinics compared with central/regional hospitals.

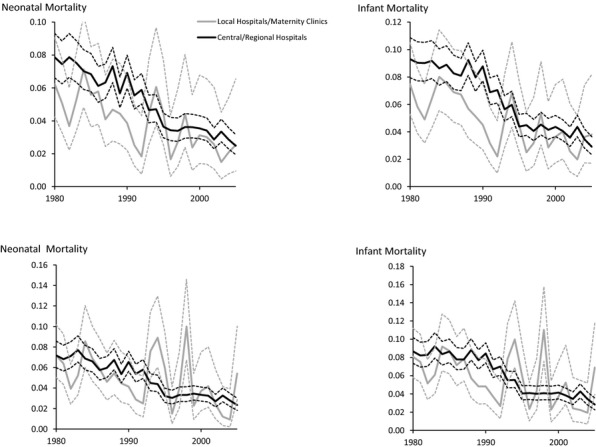

For babies with a birthweight of 2,500 g or less, there was a tendency for both neonatal and infant mortality to be higher in central/regional hospitals than in local hospitals/maternity clinics in the analyses without adjustments for risk factors (Figure2 top). However, for most years the difference in mortality between the two types of hospital was not statistically significant. With case mix adjustments, the confidence intervals for neonatal mortality did not overlap for only 2 of the 26 years (1994 and 1998) (Appendix 4). For infant mortality the confidence intervals did not overlap for 3 of the 26 years (1992, 1994, and 1998) (Appendix 5).

Figure 2.

Unadjusted (Top) and Adjusted (Bottom) Effects of Type of Hospital on Neonatal and Infant Mortality According to YearNotes. Deliveries with birthweight ≤ 2,500 g. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals given by dotted lines.

Hospital Closure

Table 2 shows the number of births 5 years before and 5 years after the closure for the catchment areas that were affected by a local hospital closure. One hospital (M) that was closed had over 4,000 deliveries from its catchment area. Five hospitals had between 2,869 and 1,131 deliveries, while the rest had fewer than 1,000 deliveries. The number of deliveries from the catchment areas that were not affected by a local hospital closure varied from 26,437 (Hospital E) to 32,684 (Hospital K).

Table 2.

Number of Deliveries Five Years before and Five Years after Local Hospital Closure for the Catchment Areas That Were Affected and Not Affected, by Local Hospital Closure

| Catchment Area That Was Affected by Local Hospital Closure (Treatment Group) |

Catchment Area That Was Not Affected by Local Hospital Closure (Control Group) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Identification | Date for Local Hospital Closure | Number of Deliveries 5 years before Closure | Number of Deliveries 5 years after Closure | Number of Deliveries 5 years before Closure | Number of Deliveries 5 years after Closure |

| A | July 1979 | 1,131 | 1,108 | 28,010 | 26,432 |

| B | March 1980 | 189 | 214 | 27,625 | 26,394 |

| C | July 1982 | 353 | 364 | 26,683 | 27,036 |

| D | July 1982 | 264 | 305 | 26,683 | 27,036 |

| E | October 1985 | 733 | 745 | 26,437 | 30,364 |

| F | July 1986 | 1,860 | 2,212 | 26,684 | 31,264 |

| G | September 1988 | 2,869 | 3,204 | 28,046 | 32,570 |

| H | September 1988 | 1,599 | 1,784 | 28,046 | 32,570 |

| I | September 1988 | 1,382 | 1,589 | 28,046 | 32,570 |

| J | October 1988 | 281 | 307 | 28,124 | 32,576 |

| K | July 1994 | 605 | 607 | 32,684 | 32,020 |

| L | July 1995 | 849 | 882 | 32,628 | 32,156 |

| M | June 1999 | 4,182 | 4,059 | 32,040 | 30,448 |

The main impression from the difference-in-difference analyses is that hospital closure had no impact on infant health (Table 3).4 For neonatal mortality, none of the 13 regression coefficients for the interaction term between Closure and Period (β3) was statistically significant at conventional levels. Six of the coefficients had a negative sign, indicating that neonatal mortality improved after closure. However, little confidence should be placed on this result, as the coefficients were far from statistically significant at conventional levels.

Table 3.

The Effect of Local Hospital Closure on Neonatal and Infant Mortality (Risk Factors and Year Fixed Effect Included, But Not Reported)

| Neonatal Mortality |

Infant Mortality |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Identification | Variables | Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE |

| A (N = 55,199) | Intercept | 0.0884* | 0.0039 | 0.1064* | 0.0050 |

| Closure = 1 | −0.0069 | 0.0039 | −0.0101* | 0.0050 | |

| Period = 1 | −0.0025 | 0.0019 | −0.0028 | 0.0024 | |

| Closure × Period | −0.0013 | 0.0030 | 0.0001 | 0.0039 | |

| B (N = 53,072) | Intercept | 0.0849* | 0.0048 | 0.0959* | 0.0062 |

| Closure = 1 | 0.0099 | 0.0055 | 0.0137 | 0.0071 | |

| Period = 1 | 0.0033 | 0.0026 | 0.0038 | 0.0034 | |

| Closure × Period | −0.0127 | 0.0070 | −0.0135 | 0.0090 | |

| C (N = 53,241) | Intercept | 0.0666* | 0.0037 | 0.0849* | 0.0049 |

| Closure = 1 | 0.0075 | 0.0040 | 0.0073 | 0.0053 | |

| Period = 1 | −0.0010 | 0.0018 | −0.0014 | 0.0023 | |

| Closure × Period | −0.0027 | 0.0050 | 0.0023 | 0.0066 | |

| D (N = 53,096) | Intercept | 0.0665* | 0.0037 | 0.0846* | 0.0049 |

| Closure = 1 | 0.0042 | 0.0045 | 0.0010 | 0.0595 | |

| Period = 1 | −0.0008 | 0.0018 | −0.0011 | 0.0024 | |

| Closure × Period | 0.0035 | 0.0056 | 0.0033 | 0.0074 | |

| E (N = 57,219) | Intercept | 0.0503* | 0.0034 | 0.0694* | 0.0046 |

| Closure = 1 | −0.0071 | 0.0038 | −0.0052 | 0.0052 | |

| Period = 1 | 0.0011 | 0.0020 | −0.0005 | 0.0027 | |

| Closure × Period | 0.0034 | 0.0033 | 0.0027 | 0.0044 | |

| F (N = 60,803) | Intercept | 0.0500* | 0.0032 | 0.0702* | 0.0043 |

| Closure = 1 | −0.0022 | 0.0026 | −0.0043 | 0.0036 | |

| Period = 1 | 0.0015 | 0.0016 | −0.0010 | 0.0022 | |

| Closure × Period | 0.0039 | 0.0020 | 0.0074* | 0.0028 | |

| G (N = 65,395) | Intercept | 0.0498* | 0.0029 | 0.0621* | 0.0039 |

| Closure = 1 | −0.0052* | 0.0023 | −0.0065* | 0.0031 | |

| Period = 1 | −0.0001 | 0.0015 | −0.0035 | 0.0020 | |

| Closure × Period | 0.0020 | 0.0017 | 0.0020 | 0.0022 | |

| H (N = 62,713) | Intercept | 0.0511* | 0.0030 | 0.0628* | 0.0040 |

| Closure = 1 | −0.0019 | 0.0035 | 0.0027 | 0.0046 | |

| Period = 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0016 | −0.0002 | 0.0021 | |

| Closure × Period | −0.0012 | 0.0021 | −0.0004 | 0.0028 | |

| I (N = 62,324) | Intercept | 0.0524* | 0.0030 | 0.0640* | 0.0040 |

| Closure = 1 | −0.0018 | 0.0049 | −0.0069 | 0.0064 | |

| Period = 1 | −0.0053 | 0.0016 | 0.0004 | 0.0000 | |

| Closure × Period | 0.0035 | 0.0023 | 0.0059* | 0.0030 | |

| J (N = 60,078) | Intercept | 0.0529* | 0.0032 | 0.0639* | 0.0042 |

| Closure = 1 | 0.0050 | 0.0040 | 0.0076 | 0.0053 | |

| Period = 1 | −0.00003 | 0.0040 | 0.0004 | 0.0024 | |

| Closure × Period | −0.0056 | 0.0049 | −0.0048 | 0.0066 | |

| K (N = 64,524) | Intercept | 0.0459* | 0.0026 | 0.0529* | 0.0033 |

| Closure = 1 | −0.0010 | 0.0026 | 0.0061 | 0.0033 | |

| Period = 1 | −0.0031* | 0.0013 | −0.0026 | 0.0016 | |

| Closure × Period | 0.0009 | 0.0030 | −0.0067 | 0.0038 | |

| L (N = 64,871) | Intercept | 0.0045* | 0.0026 | 0.0535* | 0.0032 |

| Closure = 1 | −0.0014 | 0.0023 | −0.0044 | 0.0029 | |

| Period = 1 | −0.0017 | 0.0013 | −0.0033* | 0.0016 | |

| Closure × Period | −0.0022 | 0.0025 | −0.0001 | 0.0031 | |

| M (N = 67,525) | Intercept | 0.0370* | 0.0025 | 0.0409* | 0.0029 |

| Closure = 1 | −0.0014 | 0.0019 | −0.0002 | 0.0023 | |

| Period = 1 | −0.0018 | 0.0012 | −0.0008 | 0.0014 | |

| Closure × Period | 0.0005 | 0.0011 | 0.0005 | 0.0014 | |

Note. The following risk factors were included in all analyses: mother's age, immigrant status (nonwestern, western), level of education (upper secondary school, university/college), marital status. Predisposing factors of the mother: asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, heart disease, chronic hypertension, chronic kidney failure, rhematoid arthritis, preeclampsia, bleeding during pregnancy. Characteristics of the birth: birthweight ≤2,500 g, gestation length ≤37 weeks, abnormal presentation, single baby birth, previous Caesarean section, infant boy.

p < .05.

For infant mortality 2 of 13 coefficients (β3) were statistically significant (p < .01) (Hospital F and I). The signs of these two coefficients were positive, indicating that infant health outcomes became worse after closure. Five of the coefficients had a negative sign. However, their levels of statistical significance were so low that little confidence could be placed on this result.

Discussion

The results show that infant health, measured as neonatal and infant mortality, is not higher in local hospitals/maternity clinics compared to in central/regional hospitals. This is a consistent finding, both in the analyses with propensity score weighting and with our difference-in-difference analyses. A strength of the study is that the two different approaches to the analysis gave the same results.

Propensity score weighting was an appropriate method to correct for bias, since we had access to a large number of risk factors that could be used to make the treatment and control groups as similar as possible. To our knowledge, there is only one study where case mix adjustments within the field of maternity care have been done by using propensity score (Mason et al. 2011). Mason et al. (2011) used propensity score adjustments to study the effect of a prenatal program on birth outcomes within a Medicaid population of pregnant women in the United States. The adjustments were based on four variables (state, race, age, and singleton vs. twin births). From the fields outside maternity care we have identified only one study where the effect of hospital closure on health outcomes has been examined (Buchmueller, Jacobsen, and Wold 2006).5 Buchmueller, Jacobsen, and Wold (2006) found that closures led to increased traveling distance to the nearest hospital for parts of the population, which caused higher mortality rates for conditions that required emergency care, such as heart attacks and unintentional injuries.

We cannot exclude the possibility that local hospital closure in Norway may have also led to increased mortality for acute medical conditions for which immediate access to adequate medical treatment is needed. Unfortunately, we do not have access to data to test this. However, our results show that, for medical conditions that are not normally acute, such as maternity care, local hospital closure does not lead to increased mortality. Even the high-risk births that take place at local hospitals seem to go well (Figure2 and Appendices 4–5). This may be because these high-risk births have the lowest risk within the high-risk group. The mean birthweight for babies with a birthweight of 2,500 g or less who were delivered at a local hospital was 2,183 g, compared with 1,943 g for those who were born at a central/regional hospital.

A particular challenge when using propensity score weighting is the choice of the right risk factors. The omission of risk factors that simultaneously determine infant health and type of hospital will lead to biased results. Even though we have many relevant control variables in the propensity score analyses, we cannot exclude the possibility that there may be unobserved confounders. The assumption for the analysis of hospital closure is that such confounders do not influence the estimates. We assume that the intervention is random. This means that poor quality of care at local hospitals/maternity clinics was not the reason for the closure. Given that this condition has been met, we expect that our difference-in-difference analysis has given causal estimates of the effect of hospital closure on infant health outcomes. There are two factors that point in this direction.

First, a review of public documents about closure of local maternity units in the 1980s and 1990s shows that the decision about closure was almost exclusively based on economic arguments (Norwegian Directorate of Health 1991; Nilsen, Daltveit, and Irgens 2001). In Norway, there was a strong migration of the population from rural areas, where the local hospital were located, to urban areas, where the central/regional hospitals were located during the 1980s and 1990s.6 In many local communities, the size of the population became just too small to make it economically justifiable to keep small local maternity units open. At the same time, infrastructure and communication were substantially improved, particularly by building roads. Traveling times were not noticeably longer for the women who, after a hospital closure, had a central or regional hospital as their new maternity hospital.7

Second, our results show that for nearly all hospitals, there was no difference in infant health for the local maternity units that were closed and those that were not closed during the 5-year period before closure (Table 3).8 We also supplemented our main analyses with an additional analysis of whether mortality in the 5-year period before closure had an effect on the actual closure (Appendix 6).9 With two exceptions (Hospital I and K for infant mortality) we found no such effect for any of the local hospitals that were closed.

In Norway, there are no financial incentives, either for the hospital or the doctor, not to refer mothers at high risk. One could argue that obstetricians have incentives to avoid referring high-risk deliveries to maintain a minimum number of deliveries at their local maternity unit. In this way, the risk of the maternity unit being closed down is reduced. This is not likely. High-risk deliveries are only a small percentage of the total number of deliveries (Table 1). Therefore, a small reduction in referrals would be unlikely to strengthen the case of keeping the local maternity unit open. In addition, obstetricians run a high risk of complaints or of being accused of medical negligence if complications occur during a high-risk delivery at a local hospital, for a mother who should have been referred to a hospital with more resources. Obstetricians are probably more concerned about making correct medical assessments to avoid complications and loss of life. They are not likely to deviate from this principle to keep a few high-risk deliveries. Even when local maternity units have been closed down, obstetricians have seldom become unemployed. They could be transferred to the hospital that had taken over care of the mothers in the catchment area of the local hospital that was closed down.

In conclusion, our results show that neonatal and infant mortality are not affected by a regionalized maternity service. Of course, the authorities must continually assess whether it is economically viable to maintain small maternity units. However, our findings indicate that poor quality of local maternity units is not a justification for closing them down. Caution must be used in generalizing the findings to other countries where maternity and perinatal services are organized differently than in Norway. This applies particularly to countries where obstetricians have economic incentive not to refer high-risk deliveries to a central/regional hospital when there are medical indications for doing so.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: We wish to thank Linda Grytten for translation and language correction, and the Medical Birth Registry and Statistics Norway for providing data. This study had Strategic Research Funding from Akershus University Hospital; research grant number 2639002.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

Notes

In maternity clinics, care is provided by midwives with the supervision of general medical practitioners. There are no obstetricians and no facilities for carrying out Caesarean sections.

For four of the local hospitals that were closed down, their catchment area became the catchment area of another local hospital, or the catchment area was divided between a central/regional hospital and another local hospital.

In some studies of high-risk deliveries, the population has been limited to babies with very low birthweight (<1,500 g) and very preterm infants (<32 weeks) (Lasswell et al. 2010). It was not meaningful with our data to do analyses on these populations. The reason is that these babies were nearly always born at a central/regional hospital. For example, in 1980 the total number of babies with a very low birthweight that were born in the 43 local hospitals that then existed was 31; that is, on average less than one baby per hospital. In 2005, only five babies with a very low birthweight were born in local hospitals. The corresponding numbers for very preterm infants (gestation length <32 weeks) were 65 in 1980 and 9 in 2005.

This is also a consistent result for additional analyses where the preclosure and postclosure periods were set to fewer than 5 years (i.e., 4, 3, 2, 1 year(s)).

There are numerous studies on urban hospital closure, mainly from the United States (for a review, see Lindrooth, Lo Sasso, and Bazzoli 2003; Mullner et al. 1989). The focus of these studies is on the supply side of the market: the determinants of closure and the efficiency of the hospitals that remain in the market after the closure.

From 1980 to 2009, the proportion of the population that lived in the most central municipalities in Norway increased from 61 to 67 percent (Statistics Norway 2009).

The mean distance from the local hospital that was closed to the central/regional hospital that was the new maternity hospital was 34 km; that is a journey of about half an hour by car (http://maps.google.com/).

Indicated by the lack of statistical significance for the regression coefficient β1 for most of the hospitals (Table 3).

The dependent variable was equal to 1 for the local hospitals that were closed, and 0 for those that did not close (=the control group).

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Proportions for the Unadjusted and Adjusted Samples, 1990.

Appendix SA2: Unadjusted and Adjusted Effects of Type of Hospital on the Probability of Dying within 1 month after Birth (Neonatal Mortality) According to Year. All Deliveries. Nonoverlapping 95 percent Confidence Intervals in Bold.

Appendix SA3: Unadjusted and Adjusted Effects of Type of Hospital on the Probability of Dying within 1 year after Birth (Infant Mortality) According to Year. All Deliveries. Nonoverlapping 95 percent Confidence Intervals in Bold.

Appendix SA4: Unadjusted and Adjusted Effects of Type of Hospital on the Probability of Dying within 1 month after Birth (Neonatal Mortality) According to Year. Deliveries with Birthweight ≤2,500 g. Nonoverlapping 95 percent Confidence Intervals in Bold.

Appendix SA5: Unadjusted and Adjusted Effects of Type of Hospital on the Probability of Dying within 1 year after Birth (Infant Mortality) According to Year. Deliveries with Birth Weight ≤2,500 g. Nonoverlapping 95 percent Confidence Intervals in Bold.

Appendix SA6: The Effects of Neonatal and Infant Mortality on Local Hospital Closure (=1). Risk Factors and Year Fixed Effects Included, but Not Reported.

Appendix SA7: Author Matrix.

References

- Albers LL. Savitz DA. “Hospital Setting and Fetal Death during Labor among Women at Low Risk”. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;164:868–73. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90531-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angrist JD. “Estimation of Limited Dependent Variable Models with Dummy Endogenous Regressors: Simple Strategies for Empirical Practice”. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics. 2001;19:2–28. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist JD. Pischke J-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics. An Empiricist's Companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2009. pp. 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Berger GS, Gillings DB. Siegel E. “The Evaluation of Regionalized Perinatal Health Care Programs”. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1976;125:924–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmon LR, Barfield WD. Stark AR. “Hospital Neonatal Services in the United States: Variation in Definitions, Criteria and Regulatory Status, 2008”. Journal of Perinatology. 2009;29:788–94. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmueller TC, Jacobsen M. Wold C. “How Far to the Hospital? The Effect of Hospital Closure on Access to Care”. Journal of Health Economics. 2006;25:740–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SK. Macfarlane A. “Safety and Place of Birth in Scotland”. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 1995;17:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Perinatal Health. Toward Improving the Outcome of Pregnancy: Recommendations for the Regional Development of Maternal and Perinatal Health Services. White Plains, NY: March of Dimes National Foundation; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Grytten J, Monkerud L. Sørensen R. “Adoption of Diagnostic Technology and Variation in Caesarean Section Rates: A Test of the Practice Style Hypothesis in Norway”. Health Services Research. 2012;47:2169–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grytten J, Skau I. Sørensen R. “Do Expert Patients Get Better Treatment Than Others? Agency Discrimination and Statistical Discrimination in Obstetrics”. Journal of Health Economics. 2011;20:163–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder VS, Stuart EA. Anthony JC. “Propensity Score Techniques and the Assessment of Measured Covariate Balance to Test Causal Associations in Psychological Research”. Psychological Methods. 2010;15:234–49. doi: 10.1037/a0019623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein HA. “Regionalized Perinatal Care in North America”. Seminars in Neonatology. 2004;9:111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller G, Richardson DK, Schnell R, Misselwitz B, Künzel W. Schmidt S. “Are We Regionalized Enough? Early-Neonatal Deaths in Low-Risk Births by the Size of Delivery Units in Hesse, Germany 1990-1999”. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:1061–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemminki E. “Perinatal Mortality Distributed by Type of Hospital in the Central Hospital District of Helsinki, Finland”. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine. 1985;13:113–8. doi: 10.1177/140349488501300308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K. “Estimation of Causal Effects Using Propensity Score Weighting: An Application to Data on Right Heart Catheterization”. Health Services & Outcomes Research Methodology. 2001;2:259–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K, Imbens GW. Ridder G. “Efficient Estimation of Average Treatment Effects Using the Estimated Propensity Score”. Econometrica. 2003;71:1161–89. [Google Scholar]

- Irgens LM. “The Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Epidemiological Research and Surveillance throughout 30 Years”. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2000;79:435–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth T, Walker AM, Glynn RJ, Chan KA, Gaziano JM, Berger K. Robins JM. “Results of Multivariate Logistic Regression, Propensity Matching, Propensity Adjustment, and Propensity-Based Weighting under Conditions of Nonuniform Effect”. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;163:262–70. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasswell SM, Barfield WD, Rochat RW. Blackmon L. “Perinatal Regionalization for Very Low-Birth-Weight and Very Preterm Infants. A Meta-Analysis”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:992–1000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeFevre M, Sanner L, Anderson S. Tsutakawa R. “The Relationship between Neonatal Mortality and Hospital Level”. The Journal of Family Practice. 1992;35:259–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie SP. Thiebaud P. 2007. “Using Propensity Scores to Adjust for Treatment Selection Bias. SAS Global Forum Paper 184-2007.

- Lindrooth RC, Lo Sasso AT. Bazzoli GJ. “The Effect of Urban Hospital Closure on Markets”. Journal of Health Economics. 2003;22:691–712. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumley J. “The Safety of Small Maternity Hospitals in Victoria 1982-84”. Community Health Studies. 1988;12:386–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1988.tb00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MV, Poole-Yaeger A, Lucas B, Krueger CR, Ahmed T. Duncan I. “Effects of a Pregnancy Management Program on Birth Outcomes in Managed Medicaid”. Managed Care. 2011;20:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield JA, Rosenblatt RA, Baldwin L-M, Chu J. Logerfo JP. “The Relation of Obstetrical Volume and Nursery Level to Perinatal Mortality”. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80:819–23. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.7.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick MC. “The Contribution of Low Birth Weight to Infant Mortality and Childhood Morbidity”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1985;31:82–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501103120204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Behovsbasert finansiering av spesialisthelsetjenesten. Oslo, Norway: Ministry of Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Care Services. En gledelig begivenhet. St. meld. nr. 12 (2008-2009) Oslo, Norway: Ministry of Health and Care Services; 2009. pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Moster D, Lie RT. Markestad T. “Relation between Size of Delivery Unit and Neonatal Death in Low Risk Deliveries: Population Based Study”. Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal & Neonatal Edition. 1999;80:F221–5. doi: 10.1136/fn.80.3.f221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullner RM, Rydman RJ, Whiteis DG. Rich RF. “Rural Community Hospitals and Factors Correlated with Their Risk of Closing”. Public Health. 1989;104:315–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen ST, Daltveit AK. Irgens LM. “Fødeinstitusjoner og fødsler i Norge i 1990-årene”. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 2001;121:3208–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Directorate of Health. Småsykehus – fremtidige oppgaver og funksjoner. Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Directorate of Health; 1991. pp. 3–91. Helsedirektoratets utredningsserie. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Directorate of Health. Et trygt fødetilbud. Kvalitetskrav til fødselsomsorgen. Oslo, Norway: Norwegain Directorate of Health; 2010. Veileder IS-1877. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Directorate of Health and Social Affairs. Retningslinjer for svangerskapsomsorgen. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health and Social Affairs; 2005. pp. 58–60. IS-1179. [Google Scholar]

- Paneth N, Kiely JL, Wallenstein S. Susser M. “The Choice of Place of Delivery: Effect of Hospital Level on Mortality in All Singleton Births in New York City”. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1987;141:60–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1987.04460010060024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM, Hernán MA. Brumback B. “Marginal Structural Models and Causal Inference in Epidemiology”. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550–60. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt RA, Reinken J. Shoemack P. “Is Obstetrics Safe in Small Hospitals? Evidence from New Zealand's Regionalised Perinatal System”. The Lancet. 1985;326:429–32. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt N, Abelsen B, Eide B. Øian P. “Fødestuer i Norge”. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 1997;117:823–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer ER. State Policies and Regional Neonatal Care. White Plains, NY: March of Dimes National Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Norway. 2009. “Sentraliseringen fortsetter” [accessed on June 3, 2013]. Available at http://www.ssb.no/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/sentraliseringen-fortsetter.

- Tracy SK, Sullivan E, Dahlen H, Black D, Wang YA. Tracy MB. “Does Size Matter? A Population-Based Study of Birth in Lower Volume Maternity Hospitals for Low Risk Women”. An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113:86–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viisainen K, Gissler M. Hemminki E. “Birth Outcomes by Level of Obstetric Care in Finland: A Catchment Area Based Analysis”. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1994;48:400–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.4.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolridge JM. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2002. pp. 128–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yu VYH. Dunn PM. “Development of Regionalized Perinatal Care”. Seminars in Neonatology. 2004;9:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlin J, Papiernik E. Bréart G The EUROPET Group. “Regionalization of Perinatal Care in Europe”. Seminars in Neonatology. 2004;9:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Proportions for the Unadjusted and Adjusted Samples, 1990.

Appendix SA2: Unadjusted and Adjusted Effects of Type of Hospital on the Probability of Dying within 1 month after Birth (Neonatal Mortality) According to Year. All Deliveries. Nonoverlapping 95 percent Confidence Intervals in Bold.

Appendix SA3: Unadjusted and Adjusted Effects of Type of Hospital on the Probability of Dying within 1 year after Birth (Infant Mortality) According to Year. All Deliveries. Nonoverlapping 95 percent Confidence Intervals in Bold.

Appendix SA4: Unadjusted and Adjusted Effects of Type of Hospital on the Probability of Dying within 1 month after Birth (Neonatal Mortality) According to Year. Deliveries with Birthweight ≤2,500 g. Nonoverlapping 95 percent Confidence Intervals in Bold.

Appendix SA5: Unadjusted and Adjusted Effects of Type of Hospital on the Probability of Dying within 1 year after Birth (Infant Mortality) According to Year. Deliveries with Birth Weight ≤2,500 g. Nonoverlapping 95 percent Confidence Intervals in Bold.

Appendix SA6: The Effects of Neonatal and Infant Mortality on Local Hospital Closure (=1). Risk Factors and Year Fixed Effects Included, but Not Reported.

Appendix SA7: Author Matrix.