Abstract

Objective

To better understand the issue of inappropriate pediatric Emergency Department (ED) visits in Italy, including the impact of the last National Health System reform.

Study Design

A retrospective cohort study was conducted with five health care providers in the Veneto region (Italy) in a 2-year period (2010–2011). ED visits were considered “inappropriate” by evaluating both nursing triage and resource utilization, as addressed by the Italian Ministry of Health in 2007. Factors associated with inappropriate ED visits were identified. The cost of each visit was calculated.

Principal Findings

In total, 134,358 ED visits with 455,650 performed procedures were recorded in the 2-year period; of these, 76,680 (57.1 percent) were considered inappropriate ED visits. Patients likely to make inappropriate ED visits were younger, female, visiting the ED during night or holiday, when the primary care provider (PCP) is not available.

Conclusion

The National Health System reform aims to improve efficiency, effectiveness, and costs by opening PCP offices 24 hours a day and 7 days a week. This study highlights the need for a deep reorganization of the Italian Primary Care System not only providing a larger time availability but also treating the parents' lack of education on children's health.

Keywords: Nonurgent, inappropriate, pediatric emergency department, health expenditure, reorganization

The aim of the Emergency Department (ED) is to address emergent or urgent health problems, whose treatment has to be immediate. ED utilization is continuously rising (Ben-Isaac et al. 2010): in the United States the number of visits increased from 96 million in 1995 to 119 million in 2006. Patients from 0 to 18 years of age account for about 25 percent of the total number of ED visits (Mistry et al. 2006). The high level of utilization of ED services is overwhelmed by an inappropriate and heavy access for nonurgent conditions. The percentage of access to ED for nonurgent reasons mainly ranges from 24 percent to 40 percent of total accesses, with peaks up to 90 percent (Carret, Fassa, and Domingues 2009). This is due also to a misperception of patients, who sometimes tend to recognize as nonurgent their health conditions: in a recent survey, figures suggest that almost 52 percent of patients and parents state that their ED visit was due to somewhat urgent or minor health problems (Haltiwanger, Pines, and Martin 2006).

Many studies have attempted to understand parents' motivations for bringing their children to the ED, although their conditions were not urgent. Accessibility problems with the primary care provider (PCP) are the most common ones, both because of the opening time and the proximity of the facility (Fieldston et al. 2012). One of the most frequent motivations is the parents' real perception of the severity of the illness (Brousseau et al. 2011), even if this proves to be different from the physician's judgment of the real urgency: 31 percent of the accesses deemed urgent by the parents are not so according to the physician (Kalidindi et al. 2010). Another reason is that EDs offer greater availability of both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

Nonurgent visits have several negative consequences not only on the patients but also on the ED and the health system. Frequent nonurgent accesses may give poor continuity of care, especially for patients with a chronic illness (Berry et al. 2008; Tsai, Liang, and Pearson 2010). ED overcrowding causes longer waiting time, leading both patients and health personnel to dissatisfaction (Carret, Fassa, and Kawachi 2007). Furthermore, highly qualified and skilled personnel in a specialized environment treat patients with nonurgent conditions who resort to ED to tackle routine pediatric medical problems at higher costs (Yoffe et al. 2011).

In Italy, primary care for children is provided by the PCP free of charge for the family: the PCP can be, on the choice of the family either a primary care pediatrician or a general practitioner who provides care for all age groups. PCPs are employed by the National Health System (NHS) and they are reimbursed on a capitation basis so that all visits to the PCP are provided at no cost for the patient's family (Farchi et al. 2010). Since the NHS separately reimburses all the health services provided by the Italian ED, a major burden is created by all those visits that could have been referred to the PCP but have been seen instead by the ED.

Several interventions have been done to try to reduce the number of nonurgent ED visits: in 2011 in Texas (US) parents were given a booklet with instructions to deal with some simple health problems at home and to make better decisions on when emergency services may be needed (Yoffe et al. 2011). In Japan a night-time telephonic triage appears to be effective in reassuring parents and avoiding night ED visits for nonurgent conditions (Maeda et al. 2009). Some factors can positively affect the number of nonurgent ED visits: high-quality primary care and primary care providers organized in a group or net of pediatricians are both associated with a decrease in the number of nonurgent ED visits (Brousseau et al. 2007; Farchi et al. 2010). In Italy, the most important corrective policy has been introducing copayments for deferrable care, to discourage inappropriate demand for ED services (Lega and Mengoni 2008).

The present economic crisis and the subsequent cut-spending reviews emphasized the nonurgent ED visits issue that appears to consistently affect the NHS. The Ministry of Health recently (September 13, 2012) enacted a law to reorganize the Primary Care System, whose aim is to improve efficiency, effectiveness, and costs by opening PCP offices 24 hours a day and 7 days a week (Monti and Balduzzi 2012). This study aims to evaluate the dimension of this problem in Veneto (Italy) and whether the changes introduced in the NHS organization might be able to reduce the number of nonurgent ED visits.

Materials and methods

Population

This study was conducted with five health care providers (Health Care Unit 8: Asolo; 9: Treviso; 12: Venezia; 16: Padova; 18: Rovigo) in the Veneto region (Italy). A health care provider, called health care unit (HCU), includes one or more general hospitals where EDs are located. Only Padova has a pediatric hospital with a pediatric ED. Data on a HCU population were collected by visiting the region's website (Direzione Sistema Statistico Regionale 2012).

Data Source

A retrospective cohort study was conducted on administrative data indicating access to ED by patients aged from 0 to 18 years over the period from January 2010 to December 2011. The data were obtained from the Accounting and Management Control Department of each HCU, with the consent of each Hospital Direction, and then were analyzed following the Italian policy on privacy and health data management. Each Accounting and Management Control Department has a different database and a particular way to collect and encode administrative data. The requested variables were the patient's gender and age, the time and date of the access, the triage code, the diagnosis, the performed procedure, and the outcome. After being received, the data were processed to be made consistent and to create two databases: one reporting each procedure performed to the single patient, and the other one containing personal and medical data.

Criteria for Defining Inappropriate ED Use

In 2007 the Italian Ministry of Health developed an algorithm to judge an ED visit as “inappropriate”(Progetto Mattoni 2007a). An ED visit is considered “inappropriate” when it meets one of the following criteria:

nursing triage code “white” (noncritical, nonurgent patients; Progetto Mattoni 2007b) and outcome “home discharge” or “leave during medical examinations” or “leave without being seen by the physician”;

nursing triage code “green” (low urgency and priority, deferrable care; Progetto Mattoni 2007b) and outcome “home discharge” or “leave during medical examinations” or “leave without being seen by the physician” with “general pediatric visit” as single procedure.

In 2008 Mistry, Brousseau, and Alessandrini, in an urgency classification methods study, stated that one of the best ways to judge an ED access as inappropriate is to link nurse triage and resource utilization methods (Mistry, Brousseau, and Alessandrini 2008).

Criteria for Defining Primary Care Provider Availability

In this study, the PCP is considered “available” in the following time period: a pediatrician or a general practitioner is in general, by contract, available during office hours (PCPa: from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., workdays), but a PCP is surely not available during the rest of the time (PCPna: from 6 p.m. to 12 a.m., from 12 a.m. to 8 a.m. and holidays).

Statistical Analysis

Frequency distribution was used to describe the demographic characteristics and the distribution of each variable. A generalized linear model was performed to identify those factors associated with inappropriate ED visits (Dobson 1990). Odds ratio (OR) and 95 percent confidence interval (CI) were calculated. Restricted cubic splines (Hastie and Tibshirani 1990; Harrell 2012) were used to model the nonlinear effect of workdays or holidays on the number of visits. The cost of each visit was calculated on the basis of the regional outpatient services price list (Regione del Veneto 2011); 95 percent CI were calculated using a bootstrap (Efron and Tibshirani 1993) sample of size 2,000. The presence of cyclic trends in the number of visits was tested by working out the ratio between the highest and the lowest seasonal peaks (Nam 1995), 95 percent CIs are also provided. All data were managed and analyzed using the R system, version 2.15.1 and RMS libraries (Harrell 2012; R Development Core Team 2012).

Results

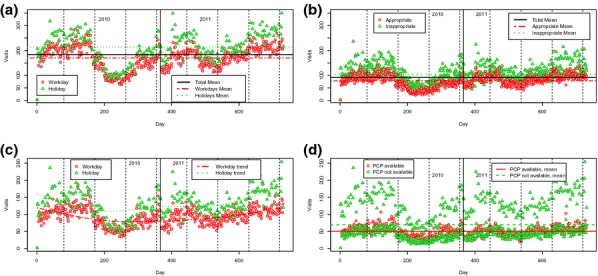

In total, 134,358 ED visits with 455,650 performed procedures were recorded in the 2-year period. Of these, 56.3 percent were made by male patients, the mean age was 6.6 years (SD = 5.5), and 0–3 is the most represented class of age (41.2 percent). Table 1 shows demographic and access characteristics. The percentage on the referral HCU population of each variable for 2010 is displayed in Table 1. Figure1a reports workday and holiday numbers of visits.

Table 1.

Demographic and Access Characteristics per Year

| 2010 | %2010 | 2011 | %2011 | %pop HCUs* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 62,972 | 46.9 | 71,386 | 53.1 | 22.2 (283,911) |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 27,582 | 43.8 | 31,145 | 43.6 | 9.7 |

| Male | 35,390 | 56.2 | 40,241 | 56.4 | 12.5 |

| Age | M 6.8 (SD = 5.6) | M 6.3 (SD = 5.4) | M 8.8 (SD = 5.5) | ||

| 0–3 | 25,167 | 40 | 30,238 | 42.4 | 8.9 |

| 4–6 | 9,904 | 15.7 | 11,798 | 16.5 | 3.5 |

| 7–11 | 12,169 | 19.3 | 13,512 | 18.9 | 4.3 |

| 12–14 | 7,202 | 11.4 | 7,927 | 11.1 | 2.5 |

| 15–18 | 8,530 | 13.6 | 7,911 | 11.1 | 3 |

| Triage | |||||

| White | 29,389 | 46.7 | 30,663 | 43 | 10.4 |

| Green | 30,128 | 47.8 | 37,212 | 52.1 | 10.6 |

| Yellow | 3,203 | 5.1 | 3,282 | 4.6 | 1.1 |

| Red | 252 | 0.4 | 229 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Outcome | |||||

| A | 51,575 | 81.9 | 60,830 | 85.2 | 18.2 |

| B | 4,836 | 7.6 | 4,694 | 6.6 | 1.7 |

| C | 3,520 | 5.6 | 3,188 | 4.5 | 1.2 |

| D | 2,242 | 3.6 | 1,875 | 2.6 | 0.8 |

| E | 509 | 0.8 | 562 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| Other | 288 | 0.5 | 237 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Health care unit | |||||

| HCU 8 (Asolo) | 6,574 | 10.4 | 14,873 | 20.8 | 13† |

| HCU 9 (Treviso) | 17,743 | 28.2 | 15,918 | 22.3 | 22.8† |

| HCU 12 (Venezia) | 18,890 | 30 | 13,442 | 18.8 | 40.3† |

| HCU 16 (Padova) | 11,278 | 17.9 | 18,536 | 26 | 13.6† |

| HCU 18 (Rovigo) | 8,487 | 13.5 | 8,617 | 12.1 | 32.8† |

| Access time | |||||

| 8–18 | 35,597 | 56.5 | 39,020 | 54.7 | 12.5 |

| 18–24 | 21,363 | 33.9 | 24,441 | 34.2 | 7.5 |

| 0–8 | 6,012 | 9.6 | 7,925 | 11.1 | 2.1 |

| Week day | |||||

| Workday | 40,849 (160.8) | 64.9 | 45,064 (179.5) | 63.1 | 14.4 |

| Holiday | 22,123 (197.5) | 35.1 | 26,322 (226.9) | 36.9 | 7.8 |

| Month | |||||

| January | 5,724 | 9.1 | 4,553 | 6.4 | 2 |

| February | 6,322 | 10 | 5,832 | 8.2 | 2.2 |

| March | 6,628 | 10.5 | 6,411 | 9 | 2.3 |

| April | 6,941 | 11 | 6,081 | 8.5 | 2.4 |

| May | 7,279 | 11.6 | 4,843 | 6.8 | 2.6 |

| June | 5,648 | 9 | 4,284 | 6 | 2 |

| July | 3,886 | 6.1 | 5,701 | 8 | 1.4 |

| August | 2,796 | 4.4 | 5,821 | 8.2 | 1 |

| September | 2,773 | 4.4 | 6,300 | 8.8 | 1 |

| October | 4,260 | 6.8 | 7,142 | 10 | 1.5 |

| November | 4,916 | 7.8 | 6,996 | 9.8 | 1.7 |

| December | 5,799 | 9.2 | 7,422 | 10.4 | 2 |

| Season | |||||

| Spring | 20,647 | 32.8 | 16,167 | 22.7 | 7.3 |

| Summer | 10,020 | 15.9 | 16,807 | 23.5 | 3.5 |

| Autumn | 13,620 | 21.6 | 21,230 | 29.7 | 4.8 |

| Winter | 18,685 | 29.7 | 17,182 | 24.1 | 6.6 |

Referred to the 0- to 18-year-old population in 2010 resident in the considered health care units (HCU).

Referred to the 0- to 18-year-old population in 2010 resident in the same health care unit.

A = Home discharge; B = Discharge to outpatient facilities; C = Hospital admission; D = Leave during medical examinations; E = Leave without being seen by the physician; M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation.

Figure 1.

From Left Upper Corner. (a) Number of Visits per Day: Workday/Holiday. (b) Number of Visits per Day: Appropriate/Inappropriate. (c) Number of Inappropriate Visits: Workday/Holiday. (d) Number of Inappropriate Visits: Primary Care Provider (PCP) Available/Not Available

When the Italian Ministry of Health algorithm was applied, the result was 76,680 (57.1 percent) inappropriate ED visits (Figure1b). Values of inappropriateness results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inappropriate Visits Demographic and Access Characteristics per Year

| 2010 |

2011 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inappropriate (N; %) | Inappropriate (N; %) | |||

| Total | 36,647 | 58.2 | 40,033 | 56.1 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 16,059 | 58.2 | 17,575 | 56.4 |

| Male | 20,588 | 58.2 | 22,458 | 55.8 |

| Age | ||||

| 0–3 | 14,622 | 58.1 | 17,831 | 59 |

| 4–6 | 5,917 | 59.7 | 6,740 | 57.1 |

| 7–11 | 6,872 | 56.5 | 7,098 | 52.5 |

| 12–14 | 4,156 | 57.7 | 4,046 | 51 |

| 15–18 | 5,080 | 59.5 | 4,318 | 54.6 |

| Triage | ||||

| White | 26,188 | 89.1 | 27,441 | 89.5 |

| Green | 10,459 | 34.7 | 12,592 | 33.8 |

| Yellow | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Red | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Outcome | ||||

| A | 34,591 | 67.1 | 38,104 | 62.6 |

| B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 1,588 | 70.8 | 1,428 | 76.2 |

| E | 468 | 91.9 | 501 | 89.2 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Health care unit | ||||

| HCU 8 (Asolo) | 4,648 | 70.7 | 8,543 | 57.4 |

| HCU 9 (Treviso) | 9,827 | 55.4 | 8,349 | 52.5 |

| HCU 12 (Venezia) | 11,776 | 62.3 | 8,838 | 65.7 |

| HCU 16 (Padova) | 6,365 | 56.4 | 10,369 | 55.9 |

| HCU 18 (Rovigo) | 4,031 | 47.5 | 3,934 | 45.7 |

| Access time | ||||

| 8–18 | 21,020 | 59.1 | 21,990 | 56.4 |

| 18–24 | 12,081 | 56.5 | 13,317 | 54.5 |

| 0–8 | 3,546 | 59 | 4,726 | 59.6 |

| Week day | ||||

| Workday | 22,754 (89.9)* | 55.7 | 24,003 (95.6)* | 53.3 |

| Holiday | 13,893 (124)* | 62.8 | 16,030 (138.2)* | 60.9 |

| Month | ||||

| January | 3,221 | 56.3 | 2,478 | 54.4 |

| February | 3,642 | 57.6 | 3,180 | 54.5 |

| March | 3,727 | 56.2 | 3,513 | 54.8 |

| April | 3,943 | 56.8 | 3,356 | 55.2 |

| May | 4,165 | 57.2 | 2,779 | 57.4 |

| June | 3,291 | 58.3 | 2,524 | 58.9 |

| July | 2,356 | 60.6 | 3,179 | 55.8 |

| August | 1,782 | 63.7 | 3,259 | 56 |

| September | 1,650 | 59.5 | 3,337 | 53 |

| October | 2,497 | 58.6 | 4,217 | 59.1 |

| November | 2,890 | 58.8 | 3,867 | 55.3 |

| December | 3,483 | 60.1 | 4,344 | 58.5 |

| Season | ||||

| Spring | 11,874 | 57.5 | 9,132 | 56.5 |

| Summer | 6,045 | 60.3 | 9,328 | 55.5 |

| Autumn | 8,065 | 59.2 | 12,062 | 56.8 |

| Winter | 10,663 | 57.1 | 9,511 | 55.4 |

Daily mean.

A = Home discharge; B = Discharge to outpatient facilities; C = Hospital admission; D = Leave during medical examinations; E = Leave without being seen by the physician.

Factors associated with inappropriate ED visits are reported in Table 3. In the evaluated sample seasonality appears to be present: a seasonality test shows a statistically significant difference between the highest visits number in spring and lowest number of visits in summer, both in the whole sample (ratio: 1.37, CI: 1.36–1.38) and in the inappropriate ED visits sample (ratio: 1.37, CI: 1.36–1.39).

Table 3.

Generalized Linear Model for Inappropriate ED Visits. All Variables Entered in the Model

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.03 | 1.00–1.06 | <.05 |

| Male | CG | – | |

| Age | |||

| 0–3 | 2.94 | 2.78–3.09 | <.0001 |

| 4–6 | 2.32 | 2.18–2.45 | <.0001 |

| 7–11 | 1.53 | 1.44–1.61 | <.0001 |

| 12–14 | 1.17 | 1.10–1.24 | <.0001 |

| 15–18 | CG | – | |

| Health care unit | |||

| HCU 8 (Asolo) | CG | – | |

| HCU 9 (Treviso) | 0.43 | 0.40–0.44 | <.0001 |

| HCU 12 (Venezia) | 0.55 | 0.53–0.58 | <.0001 |

| HCU 16 (Padova) | 1.38 | 1.32–1.44 | <.0001 |

| HCU 18 (Rovigo) | 0.48 | 0.46–0.51 | <.0001 |

| Access time | |||

| 8–18 | CG | – | |

| 18–24 | 1.19 | 1.15–1.22 | <.0001 |

| 0–8 | 1.47 | 1.41–1.54 | <.0001 |

| Week day | |||

| Workday | CG | – | |

| Holiday | 1.39 | 1.35–1.43 | <.0001 |

| PCP availability | |||

| PCPa | CG | – | |

| PCPna | 1.2 | 1.13–1.27 | <.0001 |

| Season | |||

| Spring | 1.01 | 0.97–1.05 | |

| Summer | 0.86 | 0.82–0.9 | <.0001 |

| Autumn | CG | – | |

| Winter | 1.05 | 1.01–1.09 | <.05 |

OR = Odds ratio; CI = Confidence interval; CG = Comparison group.

Costs are lower in those periods when PCPs are available (PCPa: from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., workdays) than in those periods when PCPs are not available (PCPna: from 6 p.m. to 12 a.m., from 12 a.m. to 8 a.m. and holidays) as shown in Table 4. The entire 0- to 18-year-old population of the selected HCUs in 2010 accounts for 283,911 persons (Direzione Sistema Statistico Regionale 2012). Of those, 22.2 percent had an ED visit in 2010 and overall 12.9 percent were inappropriate.

Table 4.

ED Visits Costs

| €2010 | 95% CI | €2011 | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2,846,725 | 2,821,647–2,871,041 | 3,548,871 | 3,517,335–3,581,652 |

| Inappropriate | 1,288,847 | 1,274,500–1,303,079 | 1,469,676 | 1,453,994–1,485,876 |

| Appropriate | 1,557,878 | 1,534,559–1,580,867 | 2,079,195 | 2,049,452–2,109,785 |

| Inappropriate (PCPa) | 481,266 | 471,884.5–490,644.9 | 515,355.8 | 504,055.9–525,798.9 |

| Inappropriate (PCPna) | 807,580.9 | 795,865.6–819,220.3 | 954,319.9 | 941,764.3–966,726.4 |

| Appropriate (PCPa) | 596,918.7 | 582,246.1–612,570.8 | 758,049.6 | 737,943.2–780,268 |

| Appropriate (PCPna) | 960,959.7 | 942,583.7–979,413.6 | 1,321,146 | 1,297,316–1,345,295 |

CI = Confidence interval; PCPa = Primary care provider available; PCPna = Primary care provider not available.

By applying these two percentages to the whole Veneto region's pediatric population (880,045; Direzione Sistema Statistico Regionale 2012), ED visits in 2010 are roughly estimated to be 195,195, 113,595 of which could be inappropriate. Health expenditure for pediatric ED visits in the whole Veneto region is calculated to be approximately € 8,824,054,of which € 3,995,067 are spent on inappropriate ED visits.

Discussion

The number of pediatric ED visits and the subsequent ED overcrowding is a concern in many nations (Ryan et al. 2005; Maeda et al. 2009; Ben-Isaac et al. 2010; Benahmed et al. 2012; Eroglu et al. 2012; Ng and Lewena 2012; Tropea et al. 2012). ED use for nonurgent conditions consistently affects the total number of visits. The percentage of access for nonurgent reasons mainly ranges from 24 to 40 percent of total accesses with peaks up to 90 percent (Carret, Fassa, and Domingues 2009). In this study, the percentage of inappropriate pediatric ED visits ranges from 58.2 percent in 2010 to 56.1 percent in 2011 (Figure1a), with a somewhat relevant variability across Local Health Units participating to the study. Although over the 2-year period most ED visits were made by males (56.2 and 56.4 percent), in this study—as in others (Carret, Fassa, and Domingues 2009)—females show higher odds of inappropriately visiting EDs (OR: 1.031; CI: 1.003–1.060; p < .05). Many authors found age as a predicting factor for inappropriate ED visits (Carret, Fassa, and Kawachi 2007; Berry et al. 2008; Carret, Fassa, and Domingues 2009; Ben-Isaac et al. 2010; Davis et al. 2010; Brousseau et al. 2011; Benahmed et al. 2012). In this study, the age class of 0- to 3-year-old patients proved to be the most likely to visit EDs for nonurgent conditions (OR: 2.935; CI: 2.784–3.085; p < .001). This probably reflects higher anxiety and need for reassurance in newborns' parents. Only few studies evaluate time and day of ED visits: in this study day time overall consultation (8 a.m. to 6 p.m.) turns out to be similar to other studies (Tsai, Liang, and Pearson 2010; Khan et al. 2011; Benahmed et al. 2012). Night time is found to be associated with higher risk of inappropriate access, as shown in another pediatric sample study (Benahmed et al. 2012). On the other hand, in a study whose sample is the whole population day time is associated with higher risk of inappropriate ED access (Tsai, Liang, and Pearson 2010). As for the day, this study shows greater access during holidays (Saturday, Sunday, or other public holidays), as shown in Figure1c. This difference can also be seen in the inappropriate ED visit group (Figure1c). Holiday ED visits are more likely to be inappropriate (OR: 1.393; CI: 1.353–1.433; p < .001). Many qualitative studies considered PCP time availability as one of the most important parental reasons to take their children to ED for nonurgent reasons (Haltiwanger, Pines, and Martin 2006; Berry et al. 2008; Carret, Fassa, and Domingues 2009; Stockwell et al. 2010; Fieldston et al. 2012; Salami, Salvador, and Vega 2012). This study also reveals that PCP availability is an important factor associated with inappropriateness: when PCPs are not available (PCPna; 6 p.m. to 8 a.m. and the whole day on Saturday, Sunday, or other holidays), ED visits are more likely to be inappropriate (Figure1d). Seasonality results show that an ED visit is nearly 37 percent more likely to be made in spring than in summer both for the whole sample and for the inappropriate ED visits group. Further investigations are needed to understand seasonality by including the patient's diagnosis and national data on viral or allergic diseases.

The Italian government has recently undertaken a spending review that is consistently affecting the National Health System. A recently enacted law should improve Primary Care System efficiency, effectiveness, and costs by opening PCP offices 24 hours a day and 7 days a week (Monti and Balduzzi 2012). This has been the first study to attempt to understand the economic impact of such a reorganization concerning the pediatric population. When considering the evaluated sample, by increasing PCP availability periods, the Primary Care System could receive up to 66.8 percent of patients making inappropriate ED visit. In terms of costs it means that in the five considered HCUs, costs could be decreased up to 27.5 percent per year (about € 350,000 per HCU). A rough cost estimation indicates that for the entire Veneto region health expenditure could decrease by € 2,426,000 or so. Understanding which is the most efficient Primary Care Model is a relevant issue to guarantee both greater time availability and improved parental education. Many authors reported that one of the most important reasons for parents to take their children to ED, after PCP time availability, is the need for reassurance and misperception of urgency (Berry et al. 2008; Carret, Fassa, and Domingues 2009; Stockwell et al. 2010; Khan et al. 2011; Fieldston et al. 2012). In 2008, parents expressed a need for education on the urgency of pediatric problems (Berry et al. 2008). In 2011, a 40 percent reduction in the number of inappropriate ED visits was observed after a parental educational program was carried out: this program basically consisted of a booklet with some instructions on how to deal with some simple health problems at home and how to make better decisions on when emergency services may be needed (Yoffe et al. 2011). By joining PCP complete time availability and permanent educational programs (starting during pregnancy), the Primary Care System might also be able to face the problem of inappropriate ED visits when PCPs are available. This aspect is not considered in the text of the law. To respond both to cost containment and educational needs, it is therefore necessary to consider not only the time availability of PCPs but also the content of the care they provide.

Study Limitations

Many studies on inappropriate ED visits use the New York University algorithm (NYU) to assess whether an ED visit is inappropriate or not (Ballard et al. 2010; Ben-Isaac et al. 2010; Tsai, Chen, and Liang 2011). This algorithm (recently validated) uses the ICD9-CM international diagnosis code to determine the probability of an ED visit to be a nonemergency, a primary care treatable emergency, a preventable or avoidable emergency, or a nonpreventable or avoidable emergency (Ballard et al. 2010). It was not possible to apply this widely used algorithm to the evaluated sample because the diagnosis code was missing in two of five HCUs databases.

Due to the anonymous transfer of data from each ED participating in the study, a sample-based validation of quality of data has not been possible. For the same reason, it has not been possible to understand if a single patient had more than one ED visit in the 2-year period: this was also done because the ID of the ED visits in the public administrative recording system is referred to the visit, not to the patient. This may affect the estimations of both the percentage of the HCU population that made an ED visit and the estimates of their standard errors (Williams 1982).

The unavailability of individual ID affected also the possibility to link each child with the PCP by whom she/he is assisted. This implied that no precise estimation of the availability of her/his PCP has been possible to be made. Nevertheless, the adoption of a strict criteria of availability, as specified above in the manuscript, which covers most if not all practical situation, should have reduced any potential bias in this sense, providing even more conservative estimates of the appropriateness of ED visits.

In Italy, there is not a common ED data collection approach among each Local Unit. Although the recording systems and protocols are largely overlapped for satisfying the needs of a unified health care management by the regional government, biases cannot be excluded. Although such biases have not been reported for the regional system, in principle, if occurring, they may have had an impact on the study estimates, in particular for what concerns the observed variability across local units, which, at the time being, remains unexplained. A wide system vision on data collection and management is needed to improve the quality of the researches on the Italian Health System for what concerns ED recordings.

Conclusions

In the evaluated HCUs the number of pediatric inappropriate ED visits is high (57.1 percent), and in 2010 health expenditure for pediatric ED visits in the whole Veneto region is calculated to be approximately € 8,824,000, of which € 3,995,067 are spent on inappropriate ED visits. Most inappropriate ED visits (66.8 percent) occur at nighttime or during holidays, when PCPs are not available. In terms of costs, providing complete PCPs time availability health expenditure for the entire Veneto region could decrease by about € 2,426,000. Many studies also indicate a parental need for health education as a reason for inappropriate ED visits. This lack of parental knowledge should be considered during the Primary Care System reorganization not only to fulfill the necessity for larger time availability but also to meet the need for children's health education.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: No external funding was secured for this study. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

References

- Ballard DW, Price M, Fung V, Brand R, Reed ME, Fireman B, Newhouse JP, Selby JV. Hsu J. “Validation of an Algorithm for Categorizing the Severity of Hospital Emergency Department Visits”. Medical Care. 2010;48(1):58–63. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd49ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benahmed N, Laokri S, Zhang WH, Verhaeghe N, Trybou J, Cohen L, De Wever A. Alexander S. “Determinants of Nonurgent Use of the Emergency Department for Pediatric Patients in 12 Hospitals in Belgium”. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2012;171(12):1829–37. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1853-y. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1853-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Isaac E, Schrager SM, Keefer M. Chen AY. “National Profile of Nonemergent Pediatric Emergency Department Visits”. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):454–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry A, Brousseau D, Brotanek JM, Tomany-Korman S. Flores G. “Why Do Parents Bring Children to the Emergency Department for Nonurgent Conditions? A Qualitative Study”. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2008;8(6):360–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau DC, Hoffmann RG, Nattinger AB, Flores G, Zhang Y. Gorelick M. “Quality of Primary Care and Subsequent Pediatric Emergency Department Utilization”. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):1131–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau DC, Nimmer MR, Yunk NL, Nattinger AB. Greer A. “Nonurgent Emergency-Department Care: Analysis of Parent and Primary Physician Perspectives”. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e375–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carret ML, Fassa AC. Domingues MR. “Inappropriate Use of Emergency Services: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Associated Factors”. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2009;25(1):7–28. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carret ML, Fassa AG. Kawachi I. “Demand for Emergency Health Service: Factors Associated with Inappropriate Use”. BMC Health Services Research. 2007;7:131. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JW, Fujimoto RY, Chan H. Juarez DT. “Identifying Characteristics of Patients with Low Urgency Emergency Department Visits in a Managed Care Setting”. Managed Care. 2010;19(10):38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Direzione Sistema Statistico Regionale. 2012. “Popolazione Residente nel Veneto” [accessed on April 12, 2012]. Available at http://statistica.regione.veneto.it/jsp/popolazionetot.jsp?anno=2010amp;x1_3=0amp;x2=1.

- Dobson AJ. An Introduction to Generalized Linear Models. London: Chapman and Hall; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York, London: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu SE, Toprak SN, Urgan O, Onur OE, Denizbasi A, Akoglu H, Ozpolat C. Akoglu E. “Evaluation of Non-Urgent Visits to a Busy Urban Emergency Department”. Saudi Medical Journal. 2012;33(9):967–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farchi S, Polo A, Franco F, Di Lallo D. Guasticchi G. “Primary Paediatric Care Models and Non-Urgent Emergency Department Utilization: An Area-Based Cohort Study”. BMC Family Practice. 2010;11:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieldston ES, Alpern ER, Nadel FM, Shea JA. Alessandrini EA. “A Qualitative Assessment of Reasons for Nonurgent Visits to the Emergency Department: Parent and Health Professional Opinions”. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2012;28(3):220–5. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318248b431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltiwanger KA, Pines JM. Martin ML. “The Pediatric Emergency Department: A Substitute for Primary Care?”. The California Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2006;7(2):26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FEJ. rms: Regression Modeling Strategies (R package version 3.5-0) 2012. [accessed on January 17, 2014]. Available at http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rms. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T. Tibshirani R. Generalized Additive Models. London: Chapman & Hall; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalidindi S, Mahajan P, Thomas R. Sethuraman U. “Parental Perception of Urgency of Illness”. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2010;26(8):549–53. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181ea71b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Y, Glazier RH, Moineddin R. Schull MJ. “A Population-Based Study of the Association between Socioeconomic Status and Emergency Department Utilization in Ontario, Canada”. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2011;18(8):836–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lega F. Mengoni A. “Why Non-Urgent Patients Choose Emergency over Primary Care Services? Empirical Evidence and Managerial Implications”. Health Policy. 2008;88(2–3):326–38. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Okamoto S, Mishina H. Nakayama T. “A Decision Analysis of the Effectiveness of the Pediatric Telephone Triage Program in Japan”. BioScience Trends. 2009;3(5):184–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RD, Brousseau DC. Alessandrini EA. “Urgency Classification Methods for Emergency Department Visits: Do They Measure Up?”. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2008;24(12):870–4. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31818fa79d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RD, Cho CS, Bilker WB, Brousseau DC. Alessandrini EA. “Categorizing Urgency of Infant Emergency Department Visits: Agreement between Criteria”. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006;13(12):1304–11. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti M. Balduzzi R. Conversione in legge del decreto-legge 13 settembre 2012, n. 158. Camera dei Deputati; 2012. [accessed on January 17, 2014]. Available at http://www.camera.it/_dati/lavori/stampati/pdf/16PDL0063150.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nam JM. “Interval Estimation and Significance Testing for Cyclic Trends in Seasonality Studies”. Biometrics. 1995;51(4):1411–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng Y. Lewena S. “Leaving the Paediatric Emergency Department without Being Seen: Understanding the Patient and the Risks”. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2012;48(1):10–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progetto Mattoni. Pronto Soccorso e sistema 118. Milestone 1.2.2 - Analisi dell'attività, descrizione dell'offerta, valutazioni di esito e di appropriatezza. Ministero della Salute; 2007a. [accessed on January 17, 2014]. Available at http://www.mattoni.salute.gov.it/mattoni/documenti/MDS_MATTONI_SSN_milestone_1.2.2_Analisi_attivit_PS_v1.0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Progetto Mattoni. Pronto Soccorso e sistema 118. Milestone 1.3 - Definizione del sistema di valutazione dei pazienti (triage PS e 118) Ministero della Salute; 2007b. [accessed on January 17, 2014]. Available at http://www.mattoni.salute.gov.it/mattoni/documenti/MDS_MATTONI_SSN_milestone_1.3_triage_v1.0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (release 2.15.1,) Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Regione del Veneto. Nomenclatore Tariffario Prestazioni Specialistiche Ambulatoriali. 2011. [accessed on January 17, 2014]. Available at http://bur.regione.veneto.it/BurvServices/Pubblica/Download.aspx?name=61_allegato_178934.pdf&type=9&storico=False. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M, Spicer M, Hyett C. Barnett P. “Non-Urgent Presentations to a Paediatric Emergency Department: Parental Behaviours, Expectations and Outcomes”. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2005;17(5–6):457–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2005.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salami O, Salvador J. Vega R. “Reasons for Nonurgent Pediatric Emergency Department Visits: Perceptions of Health Care Providers and Caregivers”. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2012;28(1):43–6. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823f2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell MS, Findley SE, Irigoyen M, Martinez RA. Sonnett M. “Change in Parental Reasons for Use of an Urban Pediatric Emergency Department in the Past Decade”. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2010;26(3):181–5. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181d1dfc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropea J, Sundararajan V, Gorelik A, Kennedy M, Cameron P. Brand CA. “Patients Who Leave without Being Seen in Emergency Departments: An Analysis of Predictive Factors and Outcomes”. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2012;19(4):439–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JC, Chen WY. Liang YW. “Nonemergent Emergency Department Visits under the National Health Insurance in Taiwan”. Health Policy. 2011;100(2–3):189–95. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JC, Liang YW. Pearson WS. “Utilization of Emergency Department in Patients with Non-Urgent Medical Problems: Patient Preference and Emergency Department Convenience”. The Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2010;109(7):533–42. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA. “Extra-Binomial Variation in Logistic Linear Models”. Applied Statistics. 1982;31:144–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yoffe SJ, Moore RW, Gibson JO, Dadfar NM, McKay RL, McClellan DA. Huang TY. “A Reduction in Emergency Department Use by Children from a Parent Educational Intervention”. Family Medicine. 2011;43(2):106–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.