Abstract

Reevesioside F, isolated from Reevesia formosana, induced anti-proliferative activity that was highly correlated with the expression of Na+/K+-ATPase α3 subunit in several cell lines, including human leukemia HL-60 and Jurkat cells, and some other cell lines. Knockdown of α3 subunit significantly inhibited cell apoptosis suggesting a crucial role of the α3 subunit. Reevesioside F induced a rapid down-regulation of survivin protein, followed by release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). Further examination demonstrated the mitochondrial damage in leukemic cells through Mcl-1 down-regulation, Noxa up-regulation and an increase of the formation of truncated Bid, tBim and a 23-kDa cleaved Bcl-2 fragment. Furthermore, reevesioside F induced an increase of mitochondria-associated acetyl α-tubulin that may also contribute to apoptosis. The caspase cascade was profoundly activated by reevesioside F. Notably, the specific caspase-3 inhibitor z-DEVD-fmk significantly blunted reevesioside F-induced loss of ΔΨm and apoptosis, suggesting that caspase-3 activation may further amplify mitochondrial damage and apoptotic signaling cascade. In spite of being a cardiac glycoside, reevesioside F did not increase the intracellular Ca2+ levels. Moreover, CGP-37157 which blocked Na+/Ca2+ exchanger on plasma membrane and mitochondria did not modify reevesioside F-mediated effect. In summary, the data suggest that reevesioside F induces apoptosis through the down-regulation of survivin and Mcl-1, and the formation of pro-apoptotic fragments from Bcl-2 family members. The loss of ΔΨm and mitochondrial damage are responsible for the activation of caspases. Moreover, the amplification of caspase-3-mediated signaling pathway contributes largely to the execution of apoptosis in leukemic cells.

Keywords: Reevesioside F, Na+/K+-ATPase α3 subunit, Survivin, Mitochondrial damage, Bcl-2 family of protein

1. Introduction

Several members of cardiac glycosides, a class of naturally derived compounds that bind to and block Na+/K+-ATPase, have long been in clinical therapy for the treatment of atrial arrhythmia and heart failure [1,2]. Recently, the inhibitors of Na+/K+-ATPase have attracted much interest in anticancer research. A variety of human cancers have been found to differentially express varying levels of Na+/K+-ATPase subunit isoforms. Certain isoforms have been demonstrated to be up-regulated in specific cancers [3–5]. Moreover, numerous findings reveal that particular Na+/K+-ATPase isoforms may be a marker for the progression of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cancers [6], suggesting that Na+/K+-ATPase can be a target for anticancer therapy. Consistent to the notion, a lot of preclinical data demonstrate that cardiac glycosides display anti-proliferative as well as apoptotic activities in various cancers, including prostate, breast, lung, leukemia and colorectal cancers [2–4,7,8]. Furthermore, cardiac glycoside-based anticancer drugs are currently under clinical trials [2,9].

Cardiac glycosides induce anticancer activity through various mechanisms, including an increase of intracellular Ca2+ levels, up-regulation of death receptors, down-regulation of survivin, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), induction of p21Cip1 and inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α synthesis [10–13]. It is noteworthy that although some of the mechanisms are Ca2+-dependent activities that are attributed to the inhibition of Na+/K+-ATPase, cardiac glycosides can also regulate numerous cellular processes via mechanisms that are beyond the well-established role in ion homeostasis [2]. The anti-leukemic activities of cardiac glycosides have also been documented through a blockade of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway, resulting in decreased expression levels of pro-survival proteins, induction of mitochondrial stress and activation of caspase cascades [8,14]. Although cardiac glycosides show anticancer potential, the therapeutic window is limited by the cardiotoxic effects, including arrhythmogenic effects [15]. However, the toxic effects are dependent on the dosage, the characters of the cardiac glycosides and the selectivity between cancer cells and cardiac cells. It is, therefore, anticipated that novel chemotherapeutics specifically targeting leukemic cells can be successfully developed.

Recently, the bioassay-guided fractionation of the root of Reevesia formosana led to the isolation of new cardiac glycosides in our work [16]. The present study showed that reevesioside F displayed potent activity against several leukemia cell lines, including HL-60 (human promyelocytic leukemia cells), CCRF-CEM (human acute lymphocytic leukemia cells) and Jurkat (human acute lymphocytic leukemia cells). Therefore, the anti-proliferative and apoptotic signaling pathways of reevesioside F have been identified.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

RPMI-1640 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin, and all other tissue culture regents were obtained from GIBCO/BRL Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Antibodies to GAPDH, Na+/K+-ATPase α3 subunit, Bcl-2, Bid, Bak, Bax, Mcl-1, Noxa, Bim, cytochrome c and anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgGs were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies to α-tubulin, poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP), acetyl histone H3Lys9, γ-H2A.X, calnexin and caspase-3, -7, -8 and -9 were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Boston, MA). Methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), propidium iodide (PI), phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), leupeptin, dithiothreitol (DTT), Triton X-100, RNase, aprotinin, sodium orthovanadate and all of the other chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Reevesioside F (Fig. 1A) was isolated from the root of Reevesia formosana. The purification and identification of reevesioside F were published elsewhere [16].

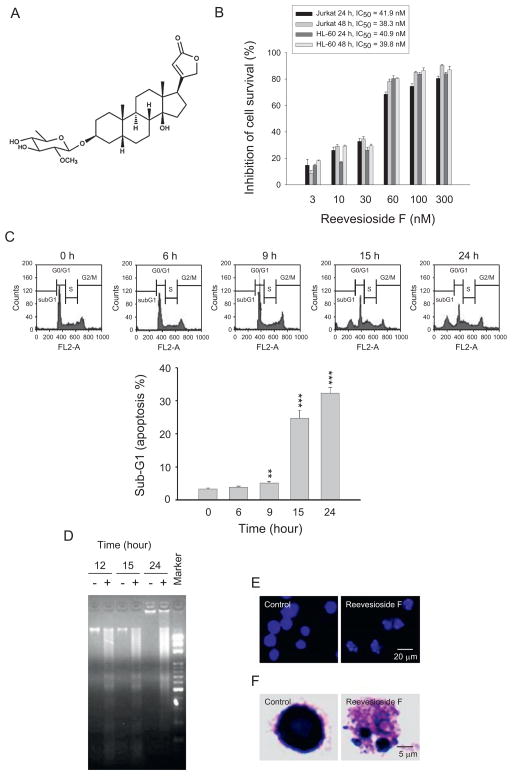

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of reevesioside F and identification of apoptotic effect. (A) Chemical structure of reevesioside F. (B) Graded concentrations of reevesioside F were added to the cells for 24 or 48 h. The cytotoxic effect was determined by MTT assay. (C) HL-60 cells were treated in the absence or presence of reevesioside F (100 nM) for the indicated times. After the treatment, the cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide to analyze DNA content by FACScan flow cytometer. (D) HL-60 cells were treated in the absence or presence of reevesioside F (100 nM) for the indicated times. DNA was electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel and stained with SYBRGreen. (E and F) HL-60 cells were treated with or without reevesioside F (100 nM) for 24 h. Microscopic examination was performed to detect apoptosis by nuclear staining with DAPI and Giemsa stain, respectively. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three to five independent experiments. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with the control.

2.2. Cell lines and cell culture

HL-60 (promyelocytic leukemia) and Jurkat (T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia) were from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS (v/v) and penicillin (100 U/ml)/streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in 5% CO2/95% air.

2.3. Mitochondrial MTT reduction activity assay

Cells were incubated in the absence or presence of the compound for the indicated concentrations and times. After the treatment, the mitochondrial MTT reduction activity was assessed. MTT was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 5 mg/ml and filtered. From the stock solution, 10 μl per 100 μl of medium was added to each well, and plates were gently shaken and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. After the loading of MTT, the medium was replaced with 100 μl acidified β-isopropanol and was left for 5–10 min at room temperature for color development. The 96-well plate was read by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (570 nm) to get the absorbance density values.

2.4. Flow cytometric assay of DNA content

After the treatment of cells with the indicated agent, the cells were harvested by trypsinization, fixed with 70% (v/v) alcohol at 4 °C for 30 min and washed with PBS. After centrifugation, cells were incubated in 0.1 ml of phosphate-citric acid buffer (0.2 M NaHPO4, 0.1 M citric acid, pH7.8) for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the cells were centrifuged and resuspended with 0.5 ml PI solution containing Triton X-100 (0.1% v/v), RNase (100 μg/ml) and PI (80 μg/ml). DNA content was analyzed with FACScan and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

2.5. DNA fragmentation assay

After the treatment, cells were collected in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 7.0 and 250 mM sucrose on ice. Total DNA was extracted by Genomic DNA kits (Geneaid, Taiwan). DNA was subsequently subjected to electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels containing SYBR® green I (1:250 dilution of stock in TE buffer) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and visualized under UV light.

2.6. Confocal microscopic examination with DAPI staining

After the treatment, the cells were fixed with 100% methanol at −20 °C for 5 min and incubated in 1 μg/ml DAPI for nuclear staining, or in the indicated antibodies for the detection of specific proteins. The cells were analyzed by a confocal laser microscopic system (Leica TCS SP2).

2.7. Microscopic observation of cell morphology

After the treatment, cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in 200 μl of PreserveCyt solution (PBS plus methanol). The suspension was passed through a Thinprep processing machine, and the cells were collected. The slides were fixed in 95% alcohol and then stained with Wright-Giemsa for 5 min at room temperature. Stained cells from each treatment group were examined under an Olympus fluorescence microscope.

2.8. Transfection of HL-60 cells with α3 subunit siRNA

Protein expression in HL-60 cells was induced using electroporation. Cells were resuspended in 250 μl of BTXpress Solution (BTX Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Cells were placed in an Eppendorf tube and α3 silencing RNA (50 nM; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added; cells were then transferred into a 4-mm gap cuvette and electroporated with a BTX ECM 830 using a single pulse at 275 V, 950 μF for 14 ms. Cuvette contents were transferred to a six-well plate, media was removed and replaced. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with 100 nM of reevesioside F for 24 h. The cells were harvested for flow cytometric analysis of PI staining or the protein was collected for Western blot analysis.

2.9. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)

JC-1, a mitochondrial dye staining mitochondria in living cells in a membrane potential-dependent fashion, was used to determine ΔΨm. Cells were treated in the absence or presence of the indicated agent. Thirty minutes before the termination of incubation, the cells were incubated with JC-1 (final concentration of 2 μM) at 37 °C for 30 min. The cells were finally harvested and the accumulation of JC-1 was determined using flow cytometric analysis.

2.10. Western blotting

After the treatment, cells were harvested with trypsinization, centrifuged and lysed in 0.1 ml of lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 50 mM NaF and 100 μM sodium orthovanadate. In some experiments, the mitochondrial/cytosol fractionation kit (Biovision, Mountain View, CA) was used to separate mitochondrial and cytosolic fraction. Total protein was quantified, mixed with sample buffer and boiled at 90 °C for 5 min. Equal amount of protein (30 μg) was separated by electrophoresis in 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes and detected with specific antibodies. The immunoreactive proteins after incubation with appropriately labeled secondary antibody were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK).

2.11. Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ level

After incubation with fluo-3/AM (5 μM) for 30 min, cells were washed twice and incubated in fresh medium. Vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or reevesioside F was added to cells and intracellular Ca2+ level was measured by flow cytometric analysis.

2.12. Data analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM for the indicated number of separate experiments. Statistical analysis of data for multiple groups is performed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Student’s t-test is applied for comparison of two groups. P-values less than 0.05 are statistically considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Reevesioside F induces anti-proliferative and apoptotic activity

HL-60 (human promyelocytic leukemia cells) and Jurkat (human acute lymphocytic leukemia cells) were used to determine the anti-proliferative and apoptotic activity of reevesioside F. The data by MTT assay showed that reevesioside F induced a potent inhibition of cell survival with IC50 values in ten nanomolar range (Fig. 1B). Flow cytometric analysis of DNA staining showed that reevesioside F induced a time-dependent increase of hypodiploid (sub-G1) DNA content (Fig. 1C). The programmed cell death was also examined using DNA fragmentation assay (Fig. 1D) and microscopic examination of DAPI and Wright-Giemsa staining (Fig. 1E and F). The data revealed that reevesioside F induced a potent apoptotic activity in leukemic cells.

3.2. Levels of Na+/K+ ATPase α3 subunit correlate well with reevesioside F-induced activity

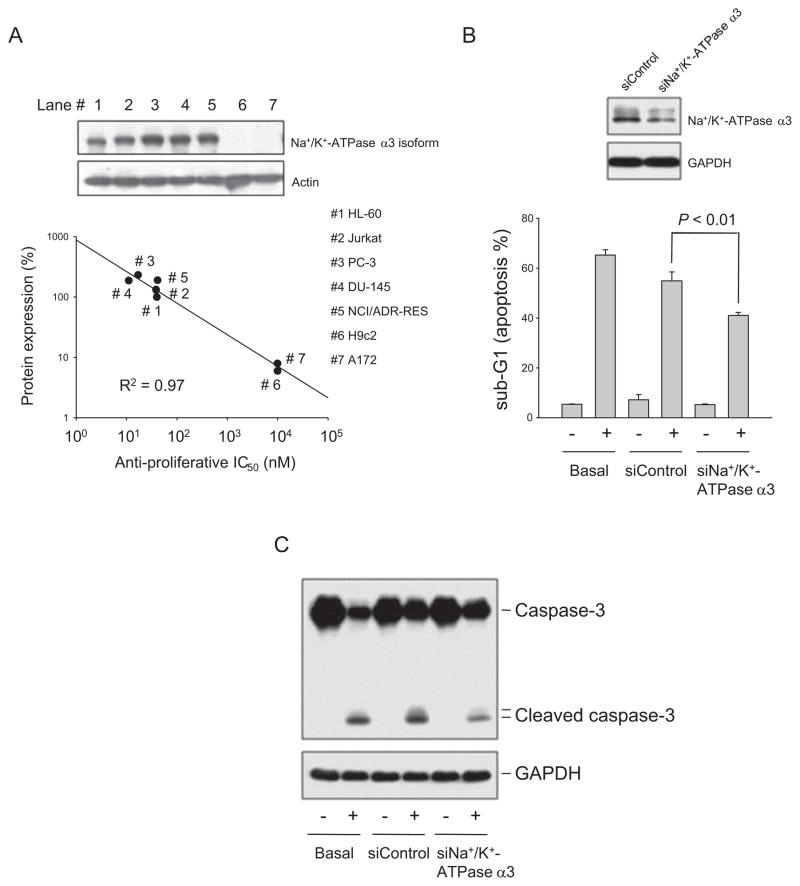

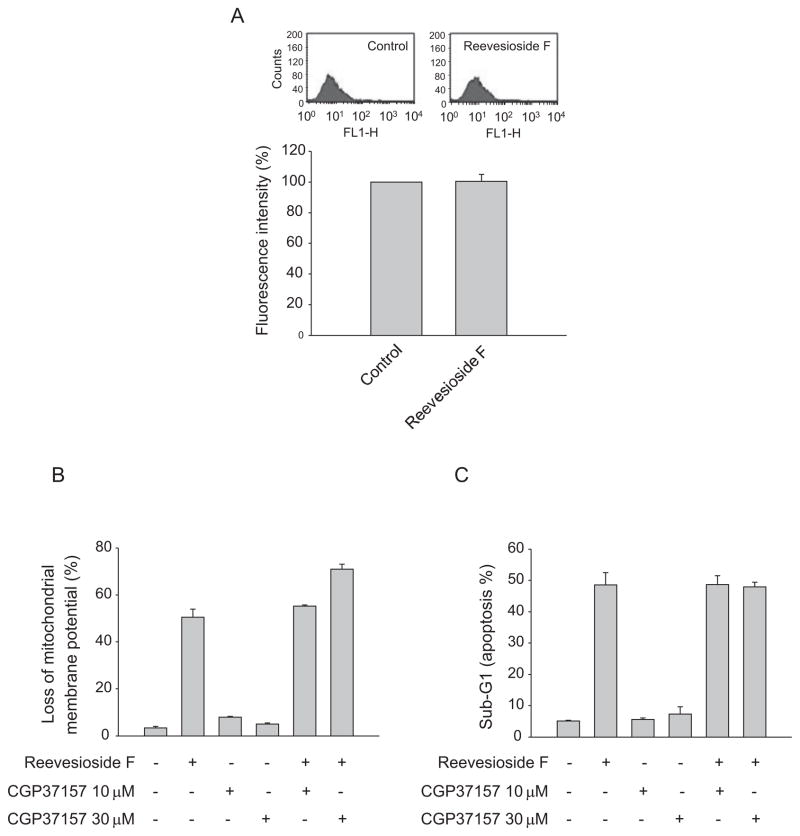

Cardiac glycosides have been documented to bind to and block Na+/K+-ATPase, leading to the accumulation of intracellular Na+ which in turn triggers an increase of intracellular Ca2+ levels through the activation of Na+/Ca2+ exchanging system. In addition to ion pumping activity, certain subunit of Na+/K+-ATPase has been reported to conduct non-pumping functions [3,5]. After the examination of protein expression of Na+/K+-ATPase subunits and anti-proliferative activity of reevesioside F in several cancer cell lines, the data revealed that the expression levels of α3 subunit highly correlated with the anti-proliferative activity (Fig. 2A). The knockdown of Na+/K+-ATPase α3 subunit significantly rescued reevesioside F-induced apoptosis and the cleavage of caspase-3 (Fig. 2B and C). However, reevesioside F did not modify the intracellular Ca2+ concentration using flow cytometric analysis of fluo-3 staining (Fig. 3A). Further functional identification using the specific inhibitor CGP-37157, which blocks Na+/Ca2+ exchanger on plasma membrane and mitochondria, showed that CGP-37157 did not inhibit reevesioside F-mediated effects, including the loss of ΔΨm (Fig. 3B) and apoptotic cell death (Fig. 3C). The data suggested that reevesioside F induced the apoptotic effect through the signaling pathway independent of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization.

Fig. 2.

Identification of the functional role of Na+/K+-ATPase α3 subunit. (A) The expression of Na+/K+-ATPase α3 subunit was detected using Western blot analysis. The anti-proliferative IC50 values were determined using SRB assays except for HL-60 and Jurkat cells by MTT assays. (B and C) The parent and α3 subunit knockdown HL-60 cells were treated with or without reevesioside F (100 nM) for 24 h. The cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide to analyze DNA content by FACScan flow cytometer (B) or the cells were harvested and lysed for the detection of the protein expression by Western blot (C). The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of four independent experiments.

Fig. 3.

Effect of reevesioside F on intracellular Ca2+ concentration. HL-60 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of reevesioside F (100 nM) for 30 min (A), or treated with the indicated agents for 24 h (B and C). After the treatment, the cells were harvested for the detection of intracellular Ca2+ levels, ΔΨm and apoptosis using flow cytometric analysis of the staining with fluo-3 AM, JC-1 and propidium iodide, respectively. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

3.3. Reevesioside F regulates the expression of Bcl-2 family proteins and induces the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential

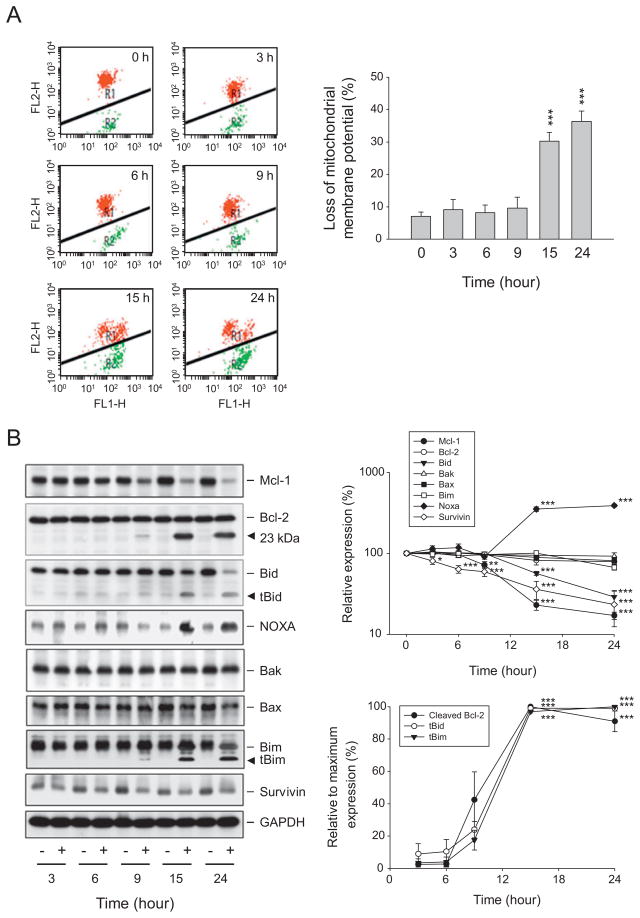

Mitochondria, the major source supplying cellular energy, are involved in numerous cellular functions, including differentiation, cell growth, cell death and the control of cell cycle [17–19]. The ΔΨm was determined using JC-1 staining to determine the integrity of mitochondrial membrane. JC-1 aggregates (red fluorescence) prefer higher ΔΨm in cells under normal condition. In response to the loss of ΔΨm, the JC-1 monomers are dominant with green fluorescence. As a result, a profound increase of green fluorescence was induced after a 15-hour exposure to reevesioside F (Fig. 4A). The data demonstrated the loss of ΔΨm and indicated the mitochondrial damage in leukemic cells responsive to reevesioside F.

Fig. 4.

Effect of reevesioside F on ΔΨm and related protein expression. HL-60 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of reevesioside F (100 nM) for the indicated times. Cells were incubated with JC-1 for the detection of ΔΨm using FACScan flow cytometric analysis (A), or cells were harvested and lysed for the detection of the indicated protein expression by Western blot (B). The expression was quantified using the computerized image analysis system ImageQuant (Amersham Biosciences). The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three to four independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with the control.

Bcl-2 family members are key regulators of the integrity of mitochondrial membrane [19,20]. Bcl-2 and Mcl-1 are two central anti-apoptotic relatives, preventing apoptosis through antagonizing pro-apoptotic family members, including Bax and Bak. The BH3-only family proteins, including Bid, Bim and Noxa, are able to block anti-apoptotic members or directly stimulate Bax or Bak [20]. Reevesioside F resulted in the down-regulation of Mcl-1, up-regulation of Noxa and an increase of formation of truncated Bid (tBid) and tBim (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, reevesioside F also induced the formation of a 23-kDa cleaved Bcl-2 fragment, a product displaying pro-apoptotic activity [21] (Fig. 4B). The data correlated well with the loss of ΔΨm, indicating that reevesioside F posed a stress and damage to the mitochondria.

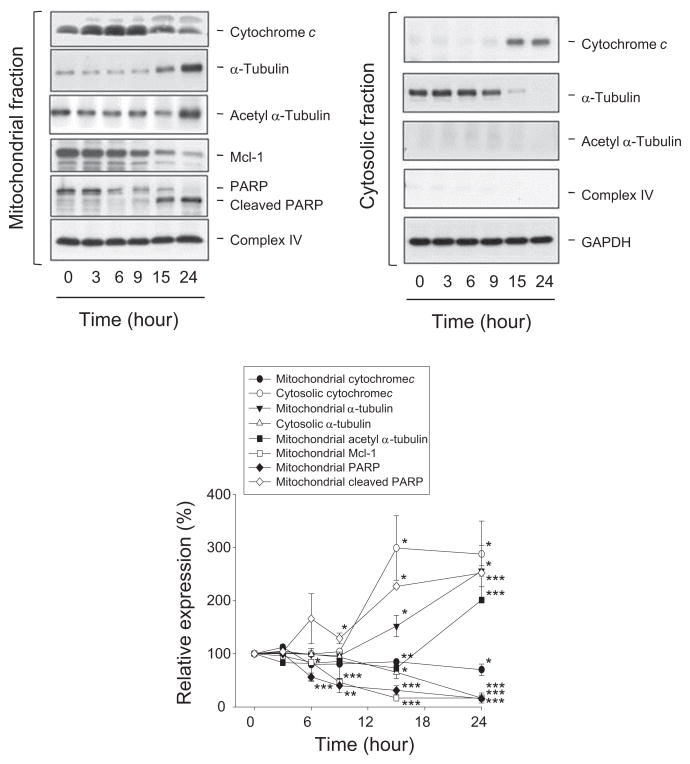

3.4. Reevesioside F induces cytochrome c release into cytosol and causes association of several factors with mitochondria

The release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria to the cytosol is a critical process for the formation of apoptosome, a multimeric complex composed of Apaf-1, cytochrome c, ATP and pro-caspase-9 for the activation of mitochondrial apoptotic pathway [22,23]. Reevesioside F induced a dramatic down-regulation of mitochondrial Mcl-1 and an increase of cytosolic cytochrome c, which confirmed the mitochondrial stress and the subsequent apoptotic cell death (Fig. 5). Furthermore, recent studies have suggested that mitochondrial PARP plays a crucial role in the repair of mitochondrial DNA [24,25]. The detection of mitochondrial PARP revealed that reevesioside F induced the cleavage of mitochondrial PARP (Fig. 5). The effect might result in the damage of mitochondrial DNA and contribute to apoptosis.

Fig. 5.

Effect of reevesioside F on mitochondria-associated proteins. HL-60 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of reevesioside F (100 nM). The cells were harvested to separate mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions for Western blot analysis and subsequently, the expression was quantified using the computerized image analysis system ImageQuant (Amersham Biosciences). The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with the control.

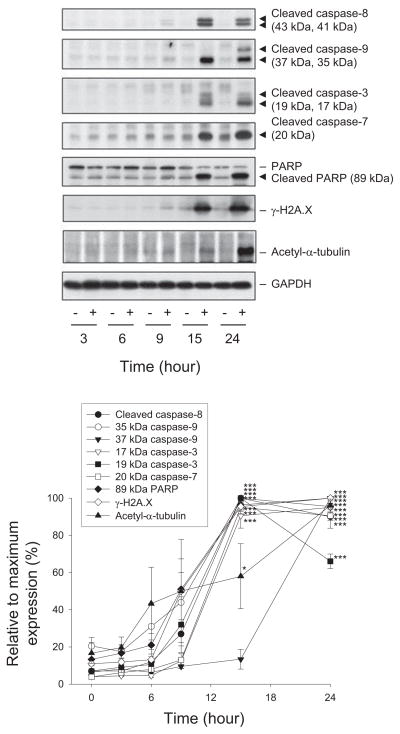

3.5. Reevesioside F induces survivin down-regulation, α-tubulin acetylation and activation of caspase cascade

Caspase family of cysteine-aspartic proteases plays a central role in both initiation and execution of cell apoptosis. The data in Fig. 6 demonstrated that reevesioside F induced a profound increase of cleaved fragments of both initiator caspases (e.g., caspase-8 and -9) and executioner caspases (e.g., caspase-3 and -7). PARP, a substrate of both caspase-3 and -7, was also cleaved in response to reevesioside F (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the formation of activated H2A.X (γ-H2A.X) indicated the activation of a DNA damage response (Fig. 6). Altogether, the data suggest the caspase-dependent DNA damage in reevesioside F-mediated apoptotic cell death. Moreover, both intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and extrinsic death receptor apoptotic pathway were triggered, because the responsible caspases (e.g., caspase-9 and -8, respectively) were activated. However, reevesioside F had no effect on the protein expressions of death receptors (e.g., Fas, DR4 and DR5) and death ligands (e.g., FasL and TRAIL) (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Effect of reevesioside F on the expression of caspases and several proteins. HL-60 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of reevesioside F (100 nM) for the indicated times. The cells were harvested and lysed for the detection of the indicated protein expression by Western blot analysis. The expression was quantified using the computerized image analysis system ImageQuant (Amersham Biosciences). The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 compared with the control.

Fig. 7.

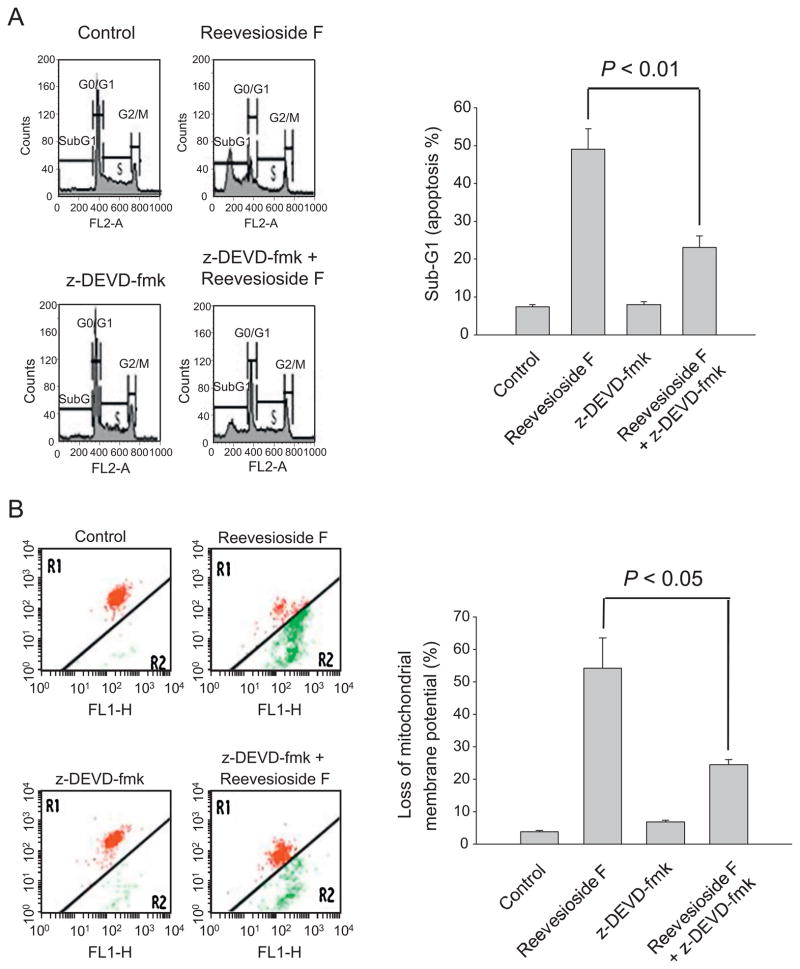

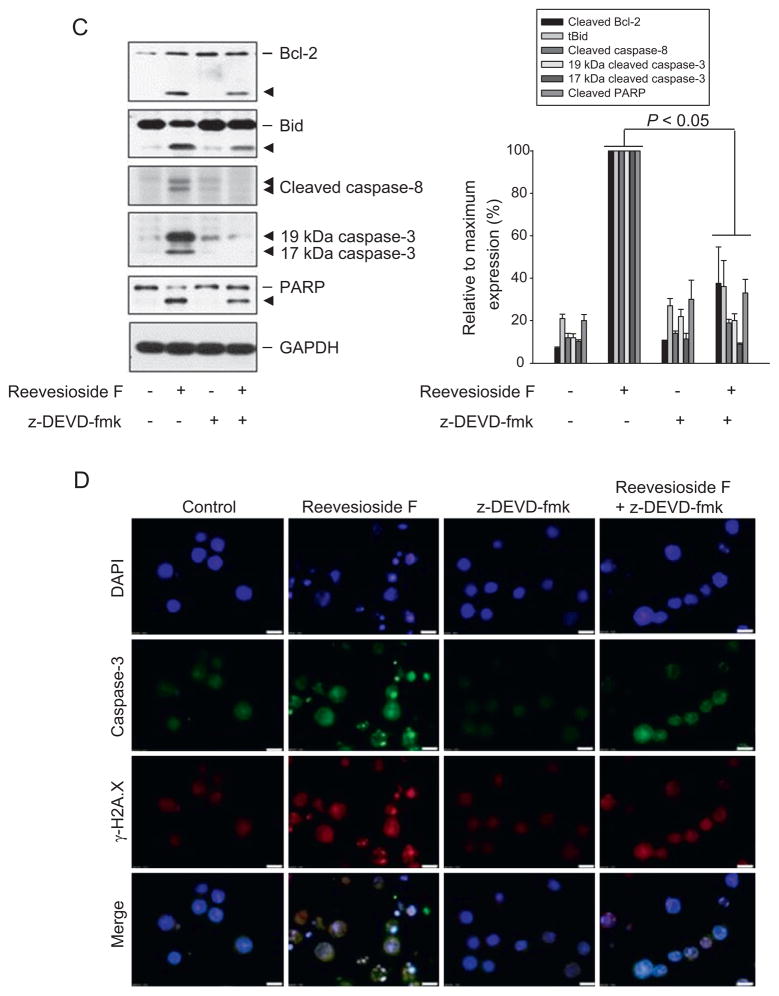

Effect of z-DEVD-fmk on reevesioside F-induced apoptosis, loss of ΔΨm and caspase expression. HL-60 cells were treated in the absence or presence of reevesioside F (100 nM) or z-DEVD-fmk (50 μM) for 24 h. After the treatment, the cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide to analyze DNA content (A), or the cells were incubated with JC-1 for the detection of ΔΨm using flow cytometric analysis. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (B). After the treatment of the indicated agent for 24 h, the cells were harvested and lysed for the detection of the indicated protein expression by Western blot analysis. The data are representative of three independent experiments (C). Double immunofluorescent staining for caspase 3 (green) and γ-H2A.X (red) was performed using fluorescence microscopic examination. DAPI staining was applied for identification of nuclei (D). Bar, 20 μm.

Survivin, the smallest and structurally unique member of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family, serves as an endogenous inhibitor of caspase activation, thereby leading to negative regulation of apoptosis. The survivin protein is highly expressed in a wide variety of cancer cells, including leukemic cells [26]. The detection of survivin protein levels showed that reevesioside F induced a time-dependent decrease of survivin expression (Fig. 4B). It could contribute to the activation of caspase cascade. Notably, the overexpression of survivin significantly rescued reevesioside F-induced apoptosis (56.8 ± 5.1% vs. 39.7 ± 4.3%, n = 3, P < 0.05), confirming the crucial role of survivin. Furthermore, survivin has been suggested to regulate the stability of tubulin [27]. Western blotting showed that α-tubulin was significantly acetylated (Fig. 6) and translocated to the mitochondria (Fig. 5) after the exposure to reevesioside F. This activity may be responsible to apoptosis because there are studies providing evidence to support that tubulin association with mitochondria is part of apoptotic mechanism [28,29]. Histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) has emerged as a major deacetylase to cause α-tubulin deacetylation [30]. However, an HDAC activity assay demonstrated that reevesioside F did not display inhibitory activity against HDACs, including HDAC6 (data not shown).

3.6. Caspase-3 activity plays a major role in reevesioside F-mediated effect

Caspase-3 is the key executioner caspase in apoptotic cascade and, once activated, this enzyme cleaves a broad spectrum of substrates, committing the cell to apoptotic death [31]. To determine the functional role of caspase-3, the specific inhibitor z-DEVD-fmk was used. z-DEVD-fmk significantly blunted reevesioside F-induced apoptosis (Fig. 7A). Similar inhibitory effect also occurred to reevesioside F-mediated loss of ΔΨm (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, z-DEVD-fmk significantly inhibited the formation of cleaved Bcl-2 and tBid, and blocked the activation of caspases and PARP cleavage (Fig. 7C). Confocal immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that z-DEVD-fmk profoundly inhibited reevesioside F-induced caspase-3 activation and γ-H2A.X nuclear localization (Fig. 7D). The data indicated that caspase-3 activity served as a central switch for the apoptotic signaling cascade.

4. Discussion

Cardiac glycosides are known to inhibit the Na+/K+-ATPase, leading to an increase of intracellular Na+ concentration which in turn triggers the exchange between intracellular Na+ and extracellular Ca2+, and ultimately results in an increase of calcium influx. The signaling pathway explains the increase of intracellular Ca2+ levels and contractility in cardiac muscle cells. However, reevesioside F did not increase the intracellular Ca2+ levels in leukemia cells. Furthermore, CGP-37157 (an inhibitor of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger) did not rescue reevesioside F-mediated effects. The data indicated that reevesioside F-induced anti-proliferative and apoptotic activities were not attributed to the inhibition of ion pumping activity by Na+/K+-ATPase. Accumulating evidence suggests that certain subunits of Na+/K+-ATPase may conduct non-pumping functions [3,5]. Both α1 and β1 subunits play a pump-independent role in epithelial junction formation and the regulation of tracheal tube-size [32]. β1 subunit has been suggested to inhibit anchorage independent growth and block tumor formation in immunocompromised mice [33]. The present study showed that the α3 subunit of Na+/K+-ATPase may play a central role on signaling the pump-independent anti-proliferative as well as apoptotic activities.

Mitochondria involve in a wide variety of cellular processes and functions, including energy production, lipid metabolism, storage of calcium ions, formation of hormones and synthesis of steroids. Therefore, mitochondria have been extensively documented to play a critical role in cell growth, survival, differentiation and apoptosis [17,18], and are considered as potential cellular targets in anticancer strategy to trigger cancer cell death [19]. Reevesioside F induced a dramatic loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and subsequent apoptosis identified by the detection of chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation, indicating the apoptotic stress caused by mitochondrial damage. The mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is dependent on Bcl-2 family of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members that interact in a complex way to regulate the integrity of mitochondrial membrane [19,20]. Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, such as Bcl-2 and Mcl-1, reside on outer mitochondrial membrane and prevent apoptosis through antagonizing pro-apoptotic family members, including Bax and Bak. The BH3-only family members (e.g., Bid, Bim and Noxa) can either block anti-apoptotic proteins or directly trigger Bax or Bak [20]. Reevesioside F induced the down-regulation of Mcl-1 protein and a profound up-regulation of Noxa, which led to the damage of outer mitochondrial membrane and triggered the release of cytochrome c to the cytoplasm, initiating the activation of caspase cascade and the execution of apoptosis [20,22].

It is noteworthy that reevesioside F induced the formation of truncated Bid (tBid). tBid contains the BH3 domain, serving as an active form of Bid and inducing the release of cytochrome c and apoptosis much more efficiently than that of Bid [34]. Notably, Mcl-1 can serve as a potent tBid-binding partner. It has been revealed that BH3 domain of tBid is necessary for Mcl-1 binding. In contrast, all three domains (BH1, BH2 and BH3) of Mcl-1 are essential for tBid binding [35]. However, reevesioside F caused a dramatic down-regulation of Mcl-1. This effect could allow more free tBid to undergo apoptotic program. The exposure to reevesioside F also induced the formation of truncated Bim (tBim). It has been reported that tBim is more potent than full length Bim protein in targeting Bcl-2 and inducing apoptosis [36,37]. Recent work has suggested that Bcl-2 activity can be regulated by its proteolytic cleavage fragment, a 23-kDa product with pro-apoptotic activity [21]. Reevesioside F resulted in the generation of 23-kDa Bcl-2 fragments as well. These data indicate that the truncated forms or active fragments of Bcl-2 family members may contribute to the amplification of apoptotic signaling cascade. Moreover, z-DEVD-fmk (a cell-permeable inhibitor of caspase-3), was able to blunt the formation of these active fragments. The data suggest that the executioner caspase-3 plays a central role in the positive feedback of apoptotic amplification in response to reevesioside F.

IAP family members bind to specific regions within caspase-3, -7 and -9 to block their activity. Survivin belongs to the IAP family. Some studies have reported the similar activity of survivin to suppress caspase-3, -7 and -9 but not caspase-8 [38], while others have shown that survivin can inhibit the release of mitochondrial apoptotic factors, such as cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) [39]. Because of the role on inhibiting apoptosis, survivin has been suggested to be a potential target for cancer chemotherapy. Importantly, elevated protein levels of survivin have been detected in a lot of primary myeloid leukemia samples [38,40]. Moreover, survivin expression in acute myeloid leukemia has been documented to positively correlate with chemotherapy resistance [38,41]. These studies provide a rationale for the development of survivin-targeted therapies. In the present work, reevesioside F induced a profound down-regulation of survivin protein expression that happened prior to the activation of caspase cascade, suggesting that survivin served as an upstream regulator in the signaling pathway.

PARP is a predominantly nuclear enzyme that is involved in DNA repair in response to a wide variety of stresses and helps cells maintain their viability. PARP is one of the major cleavage targets for caspase-3 and the cleavage of PARP normally serves as an indication of cells undergoing apoptosis [42]. Recent work on investigating the role of PARP in mitochondria has demonstrated that the abrogation of mitochondrial localization of PARP leads to the accumulation of mitochondrial DNA damage. The study provides evidence suggesting that PARP binds to different regions throughout mitochondrial DNA and plays a role in mitochondrial DNA damage signaling and repair [24,25]. In this study, reevesioside F induced the cleavage of mitochondrial PARP. The effect may, at least partly, contribute to the apoptotic mechanism.

Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization is crucial for the release of pro-apoptotic mediators from mitochondria. The permeability transition pore is responsible for mitochondrial permeability. It has been suggested that mitochondrial tubulin may participate in the mechanism from cytoskeleton to mitochondria through voltage-dependent anion channel and act as a regulator of permeability transition pore. It is, therefore, suggested that mitochondrial tubulin contributes to cell apoptosis [28,29]. The data showed that reevesioside F induced an increase of α-tubulin translocation to mitochondria. The time-dependent effect was well correlated with apoptotic cell death. Furthermore, it has been revealed that, as compared with cellular tubulin, mitochondrial tubulin is enriched in acetylated α-tubulin [29]. Similarly, our data showed that reevesioside F induced an increase of mitochondria-associated acetylated α-tubulin, which was also in a good correlation with the undergoing of apoptosis. Taken together, the formation of acetylated α-tubulin and its mitochondrial association may be involved in reevesioside F-mediated apoptosis. However, whether these effects participate in the regulation of mitochondrial permeability transition pore warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, the data suggest that reevesioside F induces apoptosis in leukemia cells independent of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization. It results in the stress and damage to the mitochondria as well as the down-regulation of Mcl-1 and survivin proteins. The execution of apoptosis is achieved through a series of signaling pathways in which the activation of caspase-3 plays a critical role. The increased caspase-3 activity induces the formation of truncated Bcl-2 family members, which are more pro-apoptotic than the parent proteins, and triggers further mitochondrial damage, leading to the amplification of caspase cascades and apoptosis in leukemia cells.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support provided by the National Science Council of the Republic of China (NSC100-2320-B-002-006-MY3 and 101-2320-B-002-018-MY3) and by the National Taiwan University (10R71809). The support by the Center for Innovative Therapeutics Discovery at National Taiwan University is also acknowledged.

References

- 1.Joubert PH, Grossmann M. Local and systemic effects of Na+/K+ ATPase inhibition. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31(Suppl 2):1–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.0310s2001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prassas I, Diamandis EP. Novel therapeutic applications of cardiac glycosides. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:926–35. doi: 10.1038/nrd2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang P, Menter DG, Cartwright C, Chan D, Dixon S, Suraokar M, et al. Oleandrin-mediated inhibition of human tumor cell proliferation: importance of Na,K-ATPase alpha subunits as drug targets. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2319–28. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang HY, O’Doherty GA. Modulators of Na/K-ATPase: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2012;22:587–605. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.690033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakai H, Suzuki T, Maeda M, Takahashi Y, Horikawa N, Minamimura T, et al. Up-regulation of Na(+), K(+)-ATPase alpha 3-isoform and down-regulation of the alpha1-isoform in human colorectal cancer. FEBS Lett. 2004;563:151–4. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajasekaran SA, Huynh TP, Wolle DG, Espineda CE, Inge LJ, Skay A, et al. Na,K-ATPase subunits as markers for epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer and fibrosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1515–24. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felth J, Rickardson L, Rosén J, Wickström M, Fryknäs M, Lindskog M, et al. Cytotoxic effects of cardiac glycosides in colon cancer cells, alone and in combination with standard chemotherapeutic drugs. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1969–74. doi: 10.1021/np900210m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juncker T, Cerella C, Teiten MH, Morceau F, Schumacher M, Ghelfi J, et al. UNBS1450, a steroid cardiac glycoside inducing apoptotic cell death in human leukemia cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaklavas C, Chatzizisis YS, Tsimberidou AM. Common cardiovascular medications in cancer therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130:177–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McConkey DJ, Lin Y, Nutt LK, Ozel HZ, Newman RA. Cardiac glycosides stimulate Ca2+ increases and apoptosis in androgen-independent, metastatic human prostate adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3807–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frese S, Frese-Schaper M, Andres AC, Miescher D, Zumkehr B, Schmid RA. Cardiac glycosides initiate Apo2L/TRAIL-induced apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells by up-regulation of death receptors 4 and 5. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5867–74. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elbaz HA, Stueckle TA, Wang HY, O’Doherty GA, Lowry DT, Sargent LM, et al. Digitoxin and a synthetic monosaccharide analog inhibit cell viability in lung cancer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;258:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prassas I, Karagiannis GS, Batruch I, Dimitromanolakis A, Datti A, Diamandis EP. Digitoxin-induced cytotoxicity in cancer cells is mediated through distinct kinase and interferon signaling networks. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2083–93. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tailler M, Senovilla L, Lainey E, Thépot S, Métivier D, Sébert M, et al. Antineoplastic activity of ouabain and pyrithione zinc in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2012;31:3536–46. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong C, Li JX, Guo HC, Zhang LN, Guo W, Meng J, et al. The H1–H2 domain of the α1 isoform of Na+-K+-ATPase is involved in ouabain toxicity in rat ventricular myocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;262:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang HS, Chiang MY, Hsu HY, Yang CW, Lin CH, Lee SJ, et al. Cytotoxic cardenolide glycosides from the root of Reevesia formosana. Phytochemistry. 2013;87:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakshminarasimhan M, Steegborn C. Emerging mitochondrial signaling mechanisms in physiology, aging processes, and as drug targets. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:174–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoshan-Barmatz V, De Pinto V, Zweckstetter M, Raviv Z, Keinan N, Arbel NVDAC. A multi-functional mitochondrial protein regulating cell life and death. Mol Aspects Med. 2010;31:227–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gogvadze V, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. Mitochondria as targets for cancer chemotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindsay J, Esposti MD, Gilmore AP. Bcl-2 proteins and mitochondria—specificity in membrane targeting for death. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:532–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortney JE, Hall BM, Bartrug L, Gibson LF. Chemotherapy induces bcl-2 cleavage in lymphoid leukemic cell lines. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:2171–8. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000033024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reubold TF, Eschenburg S. A molecular view on signal transduction by the apoptosome. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1420–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ledgerwood EC, Morison IM. Targeting the apoptosome for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:420–4. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossi MN, Carbone M, Mostocotto C, Mancone C, Tripodi M, Maione R, et al. Mitochondrial localization of PARP-1 requires interaction with mitofilin and is involved in the maintenance of mitochondrial DNA integrity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31616–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Druzhyna N, Smulson ME, LeDoux SP, Wilson GL. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase facilitates the repair of N-methylpurines in mitochondrial DNA. Diabetes. 2000;49:1849–55. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reis FR, Vasconcelos FC, Pereira DL, Moellman-Coelho A, Silva KL, Maia RC. Survivin and P-glycoprotein are associated and highly expressed in late phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Oncol Rep. 2011;26:471–8. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pavlyukov MS, Antipova NV, Balashova MV, Vinogradova TV, Kopantzev EP, Shakhparonov MI. Survivin monomer plays an essential role in apoptosis regulation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:23296–307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.237586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S. The voltage-dependent anion channel: an essential player in apoptosis. Biochimie. 2002;84:187–93. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carré M, André N, Carles G, Borghi H, Brichese L, Briand C, et al. Tubulin is an inherent component of mitochondrial membranes that interacts with the voltage-dependent anion channel. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33664–69. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hubbert C, Guardiola A, Shao R, Kawaguchi Y, Ito A, Nixon A, et al. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature. 2002;417:455–8. doi: 10.1038/417455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timmer JC, Salvesen GS. Caspase substrates. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:66–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paul SM, Palladino MJ, Beitel GJ. A pump-independent function of the Na,K-ATPase is required for epithelial junction function and tracheal tube-size control. Development. 2007;134:147–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.02710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inge LJ, Rajasekaran SA, Yoshimoto K, Mischel PS, McBride W, Landaw E, et al. Evidence for a potential tumor suppressor role for the Na,K-ATPase beta1-subunit. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:459–67. doi: 10.14670/hh-23.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katz C, Zaltsman-Amir Y, Mostizky Y, Kollet N, Gross A, Friedler A. Molecular basis of the interaction between proapoptotic truncated BID (tBID) protein and mitochondrial carrier homologue 2 (MTCH2) protein: key players in mitochondrial death pathway. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:15016–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.328377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clohessy JG, Zhuang J, de Boer J, Gil-Gómez G, Brady HJ. Mcl-1 interacts with truncated Bid and inhibits its induction of cytochrome c release and its role in receptor-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5750–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505688200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen D, Zhou Q. Caspase cleavage of BimEL triggers a positive feedback amplification of apoptotic signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1235–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308050100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng R, Oton A, Mapara MY, Anderson G, Belani C, Lentzsch S. The histone deacetylase inhibitor, PXD101, potentiates bortezomib-induced anti-multiple myeloma effect by induction of oxidative stress and DNA damage. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:385–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fangusaro JR, Caldas H, Jiang Y, Altura RA. Survivin: an inhibitor of apoptosis in pediatric cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:4–13. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu T, Brouha B, Grossman D. Rapid induction of mitochondrial events and caspase-independent apoptosis in survivin-targeted melanoma cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:39–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adida C, Recher C, Raffoux E, Daniel MT, Taksin AL, Rousselot P, et al. Expression and prognostic significance of survivin in de novo acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:196–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Invernizzi R, Travaglino E, Lunghi M, Klersy C, Bernasconi P, Cazzola M, et al. Survivin expression in acute leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:2229–37. doi: 10.1080/10428190412331283251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soldani C, Scovassi AI. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 cleavage during apoptosis: an update. Apoptosis. 2002;7:321–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1016119328968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]