Abstract

Background

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) medications have been inconsistently shown to be associated with osteoporotic fractures. The objective was to examine the association of PPI use with bone outcomes (fracture, bone mineral density [BMD])

Methods

This prospective analysis included 161,806 postmenopausal women ages 50 to 79 years without history of hip fracture enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study and Clinical Trials with a mean (SD) follow-up of 7.8 (1.6) years. Analyses were conducted on 130,487 women with complete information. Medication information was taken directly from drug containers during in-person interviews (baseline, year 3). Main outcome measures were self-reported fractures (hip [adjudicated], clinical spine, lower arm or wrist, and total fractures) and for a subsample (3 densitometry sites), 3-year change in BMD.

Results

During 1,005,126 person-years of follow-up, 1500 hip fractures, 4881 lower arm or wrist fractures, 2315 clinical spine fractures and 21247 total fractures occurred. The multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios for current PPI use were 1.00 (95% CI, 0.71 to 1.40) for hip fracture, 1.47 (CI 1.18–1.82) for clinical spine fracture, 1.26 (CI, 1.05 to 1.51) for lower arm or wrist fracture, and 1.25 (CI, 1.15 to 1.36) for total fractures. BMD measurements did not vary between PPI users and nonusers at baseline. PPI use was associated with only a marginal effect on 3-year BMD change at the hip (p=0.05) but not at other sites.

Conclusion

PPI use was not associated with hip fractures, but was modestly associated with clinical spine, lower arm or wrist and total fractures.

INTRODUCTION

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the most potent gastric acid suppressing medications available. These agents have dramatically transformed the management of acid-related disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Millions of PPI prescriptions are dispensed annually in the US and world-wide, with long-term therapy needed by many to manage the chronic symptoms of GERD.1, 2 Omeprazole was ranked 15th of all generic prescriptions and esomeprazole ranked 2nd of all brandname prescriptions dispensed in the US during 2008.1, 2

Long-term chronic PPI therapy and its attendant potent acid suppressive properties have generated concern regarding the potential deleterious affect on calcium absorption and fracture risk. Several large epidemiological studies suggest that PPI use is associated with increased osteoporotic fracture risk.3– 6 In contrast, PPI use was not associated with increased risk for hip fracture in those without fracture risk factors7 or in the analyses by Yu et al. when limiting the outcome to hip fractures.6 Histamine -2-receptor antagonists (H2RA), less potent acid suppressive agents, have also been implicated with increased risk for hip fracture to a lesser extent.4, 8

Osteoporotic fractures, with hip fractures in particular, are associated with high morbidity, mortality, and cost.9 Thus, further exploration of the association of PPI use with fracture risk is warranted, particularly since medication use may be a modifiable risk factor. Data are limited regarding the association between PPI use and change in bone mineral density (BMD) and information in this area may provide insight into the biological plausibility of the PPI-fracture association. This prospective study uses data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), which studied an ethnically and racially diverse population of postmenopausal women, to examine associations of PPI use with fracture risk (hip, clinical spine, lower arm or wrist, and total fractures) and changes in 3-year BMD (total hip, posterior-anterior spine and total body).

METHODS

Study Population

The WHI includes an observational study (OS; n = 93,676) and clinical trials (CT; n = 68,132) of hormone therapy, dietary modification, and/or calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Women were recruited between October 1, 1993, and December 31, 1998, at 40 clinical centers in the United States and were eligible if they were aged 50 – 79 years, were postmenopausal, planned to remain in the area where they lived at recruitment, and had an estimated survival of at least 3 years. Study methods have been described in detail elsewhere.10, 11 This analysis included women enrolled in the WHI-OS (n=93675) and WHI-CT (n=68,131) who had no prior hip fracture. Follow-up for this report is through September 18, 2005, for a mean (SD) of 7.8 (1.6) years. All protocols were approved by institutional review boards at participating institutions.

Outcome Ascertainment

Fracture

Total fractures were defined as all reported clinical fractures other than those of the ribs, sternum, skull or face, fingers, toes, and cervical vertebrae. Self-reported clinical fractures were collected annually (WHI-OS) or semiannually (WHI-CT) by mail and/or telephone questionnaires. Hip fractures were adjudicated by central review of radiology reports in both CT and OS cohorts. Non-hip fractures were centrally adjudicated in the CT cohort but not in the OS cohort. When self-reported fractures were confirmed by physician review, self-report was reasonably accurate for forearm/wrist (81%) and overall fractures (71%) and less so for spine fractures (51%).12 The fracture outcomes for this analysis included hip, clinical spine, arm/wrist and total fractures.

Measurement of BMD

BMD at the total hip, posterior–anterior spine, and total body was measured at baseline at 3 clinical centers among 10833 women (97% of participants enrolled in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Birmingham, Alabama; and Phoenix and Tucson, Arizona) with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry using a Hologic QDR densitometer (Hologic, Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts). Standard protocols for positioning and analysis were used by trained technicians and ongoing quality assurance program was conducted.13 Owing to missing data on BMD, PPI use and other variables, complete case analyses for hip, spine and total body were 6695, 6629, and 6677 participants respectively.

PPI Exposure

Participants were asked to bring all current prescription medications to the baseline and 3 year visit. Clinic interviewers entered each medication name directly from the containers into the WHI database, which assigned drug codes using Medispan software (First DataBank, Inc., San Bruno, California). Women reported duration of use for each current medication. Drugs in the PPI class include: esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole. Drugs in the H2RA class include: cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine, and ranitidine. Duration of use was examined in three categories (<1 year, 1 to 3 years, or >3 years). Information on dose was not recorded. Participants using both classes of medications were classified as PPI users since this medication has stronger acid suppressive effects.

Potential covariates

Information on all covariates was obtained by self-report at baseline. Baseline questionnaires ascertained information on race or ethnicity, history of fracture, and current and past smoking. Information was collected on self-report of several physician-diagnosed conditions. Physical function was measured by using the 10-item Medical Outcomes Study scale (>90 defines higher function).14 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from measured weight in kilograms and measured height in meters squared. Self-reported physical activity was measured as metabolic equivalent tasks (METs hours/week).15 Medication covariates included psychoactive medication (sum of individual agents: anxiolytics, hypnotics, antidepressants, antipsychotics and antiepileptic agents), corticosteroids, hormone replacement therapy and bisphosphonates. Dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D was measured by using a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire.16 Total calcium or vitamin D intake was defined as the sum from diet and supplements.

Statistical Analysis

The characteristics of women taking a PPI and/or H2RA at baseline were compared with those of nonusers of both medications by chi-square tests (for categorical variables) or two-sample t tests (for continuous variables). All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Multivariate analyses were conducted on participants with no missing covariate data (n=130487). Hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for fracture among PPI users or H2RA users versus nonusers were computed from Cox proportional hazards survival models for each fracture outcome. Women contributed follow-up time until the occurrence of fracture, death, or end of follow-up, whichever came first. Two models were fitted for each fracture outcome to examine the effect of potential confounding. Model 1 adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, BMI, randomization assignment for WHI-CTs, and an indicator for OS vs CT cohorts. Model 2 further adjusted for variables predictive of hip fracture from a prior WHI analysis (e.g. smoking, physical activity, general health, parent broke hip after 40, treated diabetes, history of fracture age 55+, and corticosteroid use)17 and variables that might be confounders based on a review of the literature (physical function score, medical conditions, osteoporosis, number of psychoactive medications, use of hormone therapy and bisphosphonate).4, 5, 7 Change in PPI use over time was evaluated by entering PPI use as time-dependent exposure. In addition to the main models, a similar series of proportional hazards models were run to examine associations of longer durations of use on the fracture outcomes. An a priori plan of analysis specified selected subgroup analyses for associations of PPI use on the outcomes of hip fracture and total clinical fractures by age, hormone therapy use, BMI, osteoporosis, prior non-hip fracture, calcium intake and presence of ulcer/heartburn. For the survival modeling, the proportional hazards assumption was evaluated by examining plots of the baseline hazard as a function of the exposure variables of interest as well as testing an interaction term of PPI use by log follow-up time. As a sensitivity analysis, we reran the models for baseline PPI exposure using only adjudicated fractures (spine, wrist/arm, total) from the WHI CT.

The mean BMDs according to PPI use are presented with standard errors. Multivariable linear regression methods were used to assess the association of baseline BMD with any PPI use and duration of PPI use, as well 3-year changes in BMD. To further evaluate the differences in BMD according to PPI use, the change in BMD from baseline years 3 and 6 was examined using repeated measures models adjusted for WHI trial participation and intervention and subsequently, all variables in Model 2 and a time-dependent PPI exposure.

RESULTS

Among the 161,806 women in the total cohort at baseline, 3396 (2.1%) were currently using a PPI medication and 10016 (6.2%) were using a H2RA only. Of those using a PPI medication at baseline 392 (11.5%) had used their PPI for more than 3 years, 1520 (44.8%) for 1 to 3 years, and 1484 (43.7%) for less than 1 year. Omeprazole (n=2875, 1.78%) and lansoprazole (n=521, 0.003%) were the only PPIs used. PPI users were more likely than nonusers to be obese; have osteoporosis and history of fractures; have treated diabetes or history of several health conditions; use of certain medications (e.g psychoactive medications, hormone use); have poorer physical function and poor/fair self-reported health.(Table 1)

Table 1.

| Non-user (n=148394) |

PPI User (n=3396) |

H2RA Only User (n=10016) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, years | 63.1(7.3) | 64.8 (7.0) | 64.3 (7.1) |

| Body-mass index, kg/m2 | |||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 1344 (0.9) | 10 (0.3) | 44 (0.4) |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 52024 (35.1) | 645 (19.0) | 2267 (22.6) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 50926 (34.3) | 1231 (36.2) | 3523 (35.2) |

| Obese (>30) | 42776 (28.8) | 1481 (43.6) | 4108 (41.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 122278 (82.4) | 2852 (84.0) | 8410 (84.0) |

| Black | 13354 (9.0) | 306 (9.0) | 957 (9.6) |

| Hispanic | 5985 (4.0) | 140 (4.1) | 359 (3.6) |

| American Indian | 643 (0.4) | 17 (0.5) | 53 (0.5) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4047 (2.7) | 38 (1.1) | 105 (1.0) |

| Unknown | 2087 (1.4) | 43 (1.3) | 132 (1.3) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 75042 (50.6) | 1628 (47.9) | 4759 (47.5) |

| Past | 61107 (41.2) | 1539 (45.3) | 4463 (44.6) |

| Current | 10306 (6.9) | 177 (5.2) | 659 (6.6) |

| Physical function score > 90 | 56093 (37.8) | 546 (16.1) | 1990 (19.9) |

| Parent broke hip after 40 | 18991 (12.8) | 456 (13.4) | 1260 (12.6) |

| Fracture on or after age 55 | 18191 (12.3) | 584 (17.2) | 1443 (14.4) |

| Physical activity (METS) hours/wk | |||

| 0 (Inactive) | 21777 (14.7) | 673 (19.8) | 2012 (20.1) |

| < 5 | 29314 (19.8) | 868 (25.6) | 2314 (23.1) |

| 5–12 | 33709 (22.7) | 772 (22.7) | 2286 (22.8) |

| ≥ 12 | 56636 (38.2) | 1021 (30.1) | 2953 (29.5) |

| Fair/Poor self-rated health | 12167 (8.2) | 793 (23.4) | 1733 (17.3) |

| Treated diabetes | 6312 (4.3) | 239 (7.0) | 618 (6.2) |

| Myocardial infarction/ angina | 8812 (5.9) | 518 (15.3) | 1269 (12.7) |

| Asthma or emphysema | 14063 (9.5) | 658 (19.4) | 1501 (15.0) |

| Arthritis | 67433 (45.4) | 2314 (68.1) | 6444 (64.3) |

| Osteoporosis | 10711 (7.2) | 503 (14.8) | 1061 (10.6) |

| Stomach or duodenal ulcer | 7335 (4.9) | 901 (26.5) | 2228 (22.2) |

| Moderate/severe heartburn | 10571 (7.1) | 1048 (30.9) | 3416 (34.1) |

| Psychoactive medication usec | 13962 (9.4) | 927 (27.3) | 2147 (21.4) |

| Bisphosphonate use | 2841 (1.9) | 116 (3.4) | 205 (2.0) |

| Corticosteroid use | 1104 (0.7) | 100 (2.9) | 202 (2.0) |

| Hormone therapy use | |||

| Never used | 66093 (44.5) | 1199 (35.3) | 3728 (37.2) |

| Past user | 23451 (15.8) | 606 (17.8) | 1872 (18.7) |

| Current user | 58847 (39.7) | 1591 (46.8) | 4416 (44.1) |

| Total baseline calcium intake | |||

| < 600 mg | 28607 (19.3) | 677 (19.9) | 1950 (19.5) |

| 600 – 1200 mg | 55321 (37.3) | 1271 (37.4) | 3830 (38.2) |

| > 1200 mg | 60022 (40.4) | 1331 (39.2) | 3903 (39.0) |

| Calcium supplement use | 33303 (22.4) | 658 (19.4) | 2178 (21.7) |

| Total baseline vitamin D intake | |||

| < 400 IU | 80920 (54.5) | 1792 (52.8) | 5341 (53.3) |

| 400 – 600 IU | 35346 (23.8) | 784 (23.1) | 2463 (24.6) |

| > 600 IU | 27684 (18.7) | 703 (20.7) | 1879 (18.8) |

| Vitamin D supplement use | 5887 (4.0) | 126 (3.7) | 359 (3.6) |

| WHI participation | |||

| Hormone therapy trial | 25285 (17.0) | 476 (14.0) | 1586 (15.8) |

| Dietary Modification trial | 44806 (30.2) | 932 (27.4) | 3096 (30.9) |

| Calcium vitamin D trial | 33599 (22.6) | 608 (17.9) | 2075 (20.7) |

| Observational study | 85727 (57.8) | 2124 (62.5) | 5824 (58.1) |

PPI=proton pump inhibitor; H2RA=histamine 2 receptor antagonist; METs=metabolic equivalent tasks

Data represented as n (%) unless otherwise stated.

All p values comparing differences among groups are p<.001 with exception of DM trial assignment and calcium supplement use (p= 0.002); calcium intake p=.023

Psychoactive medications include antipsychotic, antiseizure, anxiolytic, hypnotic, and antidepressant use

Fractures

During 1,005,126 person-years of follow-up, 1500 hip fractures, 4881 lower arm or wrist fractures, 2315 clinical spine fractures and 21247 total fractures occurred. The annualized rates of hip fractures were 0.147% for nonusers and 0.188% for PPI medication users.

In the fully adjusted models, PPI use was not related to risk for hip fracture (HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.40), but was related to clinical spine, lower wrist/arm and total fractures (Table 2). Those using PPIs had a 47% increased risk for clinical spine fracture (HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.18–1.82), a 26% increased risk for lower wrist/arm fractures (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.05–1.51) and a 25% increased risk for total fractures (HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15–1.36). There was no association between H2RA use and hip fracture, clinical spine, or wrist/arm but use was associated with a minimal increase in total fractures (HR 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.14). Examination of the relative hazard of hip, wrist or total fracture by duration of PPI use at baseline (Table 3) revealed no consistent trend.

Table 2.

| Non use (n= 119804) |

PPI use (n= 2731) |

H2RA use only (n=7952) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Hip (n=1500) | |||

| Model 1 | 1 (reference) | 1.21 (0.87–1.69) | 1.24 (1.02–1.50) |

| Model 2 | 1 (reference) | 1.00 (0.71–1.40) | 1.07 (0.87–1.30) |

| Clinical Spine (n=2315) | |||

| Model 1 | 1 (reference) | 2.04 (1.65–2.51) | 1.30 (1.12–1.51) |

| Model 2 | 1 (reference) | 1.47 (1.18–1.82) | 1.02 (0.87–1.20) |

| Wrist/Arm (n=4881) | |||

| Model 1 | 1 (reference) | 1.31 (1.10–1.57) | 1.07 (0.95–1.20) |

| Model 2 | 1 (reference) | 1.26 (1.05–1.51) | 1.05 (0.93–1.19) |

| Total Fractures (n=21247) | |||

| Model 1 | 1 (reference) | 1.44 (1.32–1.56) | 1.19 (1.13–1.25) |

| Model 2 | 1 (reference) | 1.25 (1.15–1.36) | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) |

PPI=proton pump inhibitor; H2RA=histamine 2 receptor antagonist; CI=confidence intervals; METs=metabolic equivalent tasks

All proportional hazards models are stratified by age group at screening and WHI Intervention arms

Model 1 adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, body mass index, enrollment in clinical trial status, indicator for cohort.

Model 2 further adjusted for smoking, physical activity (METS), general health, parent broke hip after 40, treated diabetes, history of fracture age 55+, corticosteroid use, physical function score, history of MI or angina, asthma or emphysema, arthritis, stomach or duodenal ulcer, moderate/severe heartburn, osteoporosis, number of psychoactive medications, use of hormone therapy and bisphosphonate.

Table 3.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios Relating Duration of PPI or H2RA Use to Incidence of Hip, Clinical Spine, Wrist/Arm and Total Fracturea,b

| Hip | Clinical Spine | Wrist/Arm | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of Use | Number | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

| PPI Use | |||||

| Non-user | 127756 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| < 1 year | 1204 | 1.00 (0.60–1.67) | 1.67 (1.22–2.27) | 1.55 (1.21–1.98) | 1.27 (1.13–1.44) |

| 1 – 3 years | 1218 | 0.98 (0.59–1.61) | 1.40 (1.02–1.92) | 0.92 (0.67–1.26) | 1.19 (1.05–1.35) |

| > 3 years | 309 | 1.01 (0.42–2.43) | 1.11 (0.59–2.07)c | 1.45 (0.90–2.34) | 1.30 (1.03–1.64) |

| H2RA use | |||||

| Non-user | 122350 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| < 1 year | 2326 | 1.19 (0.85–1.66) | 1.07 (0.82–1.41) | 1.02 (0.82–1.26) | 1.09 (0.99–1.20) |

| 1 – 3 years | 3331 | 0.78 (0.55–1.10) | 0.91 (0.71–1.16) | 1.09 (0.92–1.30) | 1.08 (1.00–1.18) |

| > 3 years | 2480 | 1.30 (0.96–1.75) | 1.07 (0.83–1.37) | 1.05 (0.86–1.28) | 1.06 (0.96–1.16) |

PPI=proton pump inhibitor; H2RA=histamine 2 receptor antagonist; CI=confidence intervals; METs=metabolic equivalent tasks

All proportional hazards models are stratified by age group at screening and WHI Intervention arms

Models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, body mass index, enrollment in clinical trial status, indicator for cohort, smoking, physical activity (METS), general health, parent broke hip after 40, treated diabetes, history of fracture age 55+, and corticosteroid use, physical function score, history of MI or angina, asthma or emphysema, arthritis, stomach or duodenal ulcer, moderate/severe heartburn, osteoporosis, number of psychoactive medications, use of hormone therapy and bisphosphonate.

p=0.003 for trend

Among the 140,388 women who had completed a year 3 clinic visit (87%), 68% of current PPI users at baseline were still using a PPI (1971 of 2881) 3 years later. Among the 137,507 not taking a PPI at baseline, 6211(4.5%) were taking a PPI at year 3 clinic visit. Hazard ratios for PPI use derived from time dependent Cox proportional hazards models were 1.01 (95% CI, 0.80 to 1.29) for hip fracture, 1.21 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.44) for clinical spine fracture, 1.18 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.35) for lower arm/wrist fracture and 1.19 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.27) for total fracture.

For hip fractures, there was no evidence of effect modification in the subgroups examined. For total fractures, we found an interaction between PPI use and age group (p=0.02) and history of non-hip fracture (p=0.02). The increased risk for total fractures with PPI use appeared in the age groups below 70 (HR 1.31 to 1.52), whereas women aged 70–79 years had a HR of 1.05 compared to nonusers (95% CI 0.90 to 1.22). In those with no history of fracture, risk for fracture was 32% higher in PPI users (HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.46) compared to non-users. In contrast, in those with a history of fracture, PPI users had a HR of 1.04 compared to nonusers (95% CI 0.87 to 1.24).

Sensitivity Analyses

When considering only adjudicated fractures for spine (n=628), wrist/arm (n=1791) and total fractures (n=6580) from the CT cohort, the adjusted HRs were 1.65 (95% CI 1.10–2.49), 1.11 (95% CI 0.80–1.56) and 1.27 (95% CI 1.08–1.49), respectively. Adjusting for psychoactive medications individually rather than as total number had a minimal change in effect size (e.g. hip fracture HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.72, 1.45). Further adjustment for several other medication classes associated with fracture risk (thyroid hormone replacement, thiazide diuretics, coumarin anticoagulants, loop diuretics, and beta blockers) also had a minimal effect on the effect size (e.g. hip fracture HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.71–1.39).

Bone Mineral Density

At baseline, women using PPIs had similar BMD at the hip (adjusted mean 0.87 vs 0.87 gm/cm), spine (adjusted mean 0.99 vs 0.98), and total body (adjusted mean 1.03 vs 1.02 gm/cm) compared to non-users (Table 4). Baseline BMD did not vary significantly according to duration of PPI use at any site (data not shown).

Table 4.

Three Year Changes in Mean BMD according to Baseline PPI Use

| PPI User | PPI Non-user | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Meana (SE) | N | Meana (SE) | P-Valuea | Adjusted P-Valueb | |

| Total hip (n=6695)c | ||||||

| Initial, g/cm2 | 142 | 0.865 (0.014) | 7905 | 0.869 (0.008) | 0.70 | 0.27 |

| Final, g/cm2 | 121 | 0.867 (0.015) | 6653 | 0.883 (0.009) | 0.22 | 0.06 |

| Change, % | 118 | 0.618 (0.448) | 6577 | 1.364 (0.251) | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Total spine (n=6629)c | ||||||

| Initial, g/cm2 | 134 | 0.987 (0.017) | 7671 | 0.979 (0.010) | 0.57 | 0.67 |

| Final, g/cm2 | 113 | 1.008 (0.020) | 6466 | 1.012 (0.011) | 0.83 | 0.25 |

| Change, % | 111 | 3.131 (0.580) | 6418 | 3.037 (0.322) | 0.85 | 0.94 |

| Total body (n=6677)c | ||||||

| Initial, g/cm2 | 142 | 1.025 (0.011) | 7906 | 1.018 (0.006) | 0.39 | 0.76 |

| Final, g/cm2 | 121 | 1.037 (0.012) | 6626 | 1.034 (0.007) | 0.81 | 0.58 |

| Change, % | 118 | 2.296 (0.404) | 6559 | 1.337 (0.227) | 0.005 | 0.08 |

METs=metabolic equivalent tasks

Adjusted for WHI trial participation and intervention

Adjusted for age, ethnicity, body mass index, smoking, physical activity level (METS), self-reported health, parental history of hip fractures, diabetes, history of fractures (fracture at age 55+), corticosteroid use, physical function construct, history of MI/Angina, history of asthma/emphysema, arthritis, osteoporosis, psychoactive medications use, past/current use of HT, bisphosphonates, moderate/severe stomach ulcers, moderate/severe heartburn, WHI trial participation and intervention.

Complete case analysis sample used to examine 3-year change

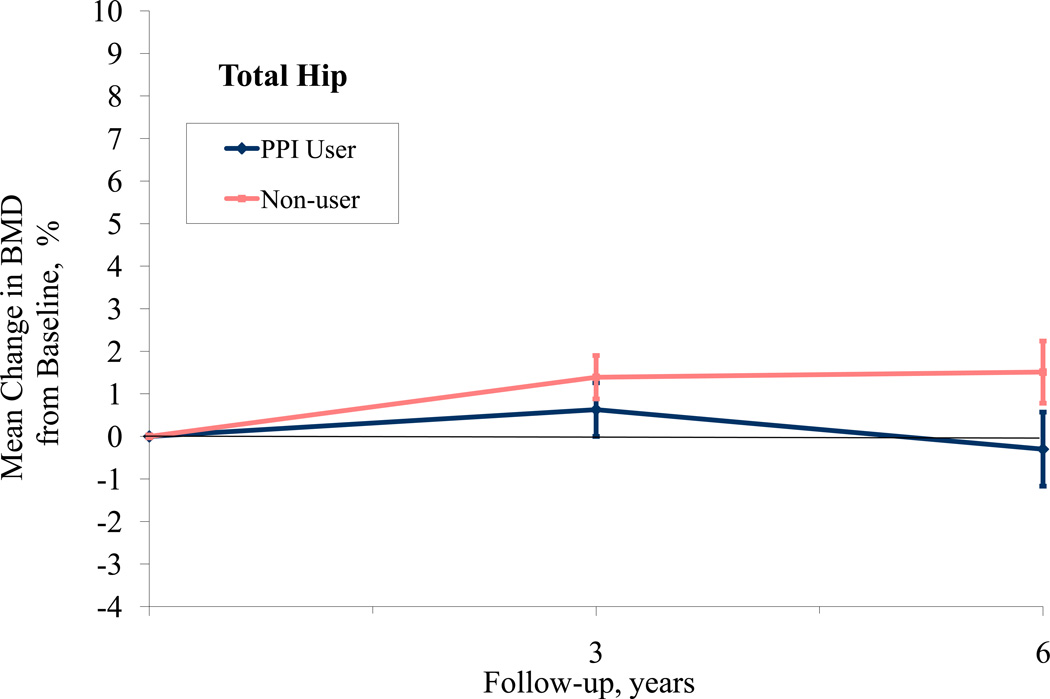

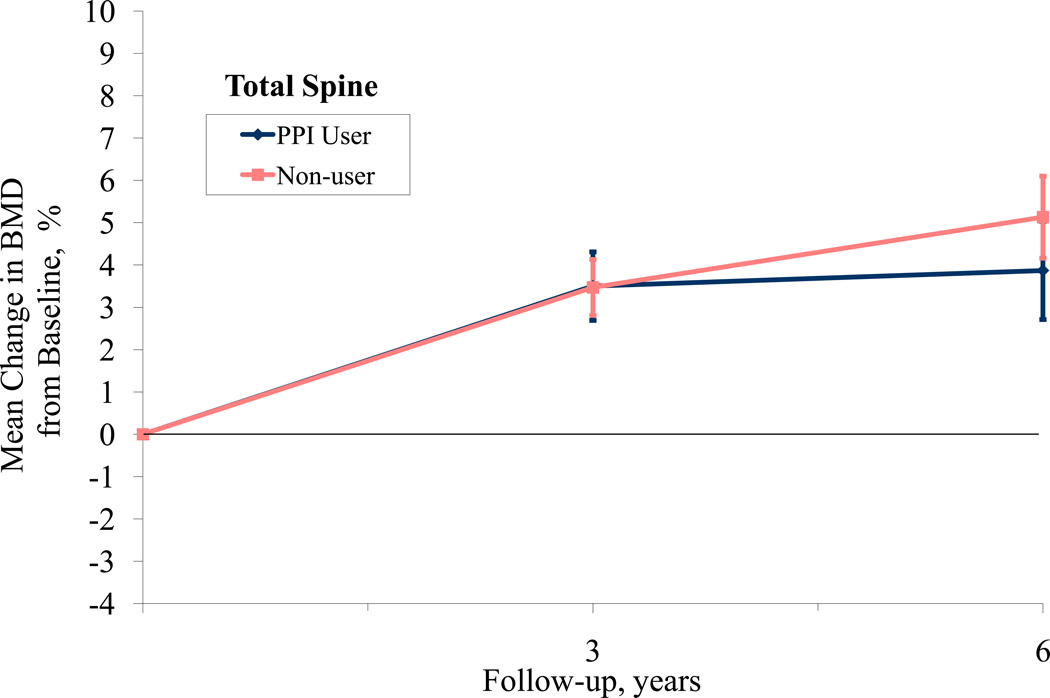

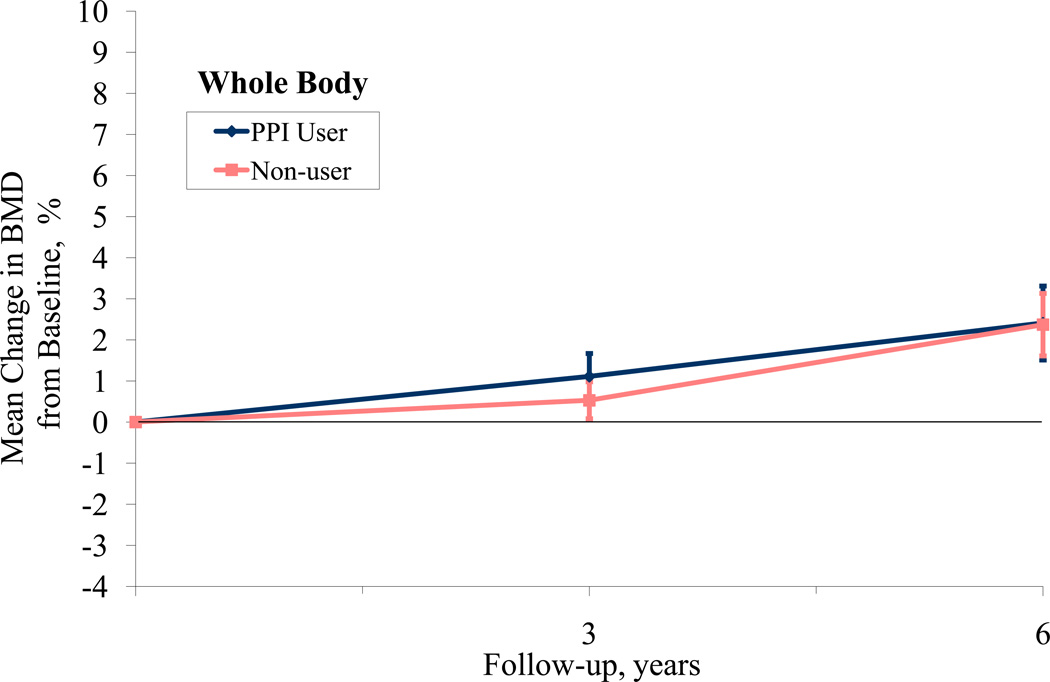

When examining 3-year BMD change from baseline, participants on average experienced small increases in BMD at all sites as some women were participating in active treatment arms in the WHI-CT involving hormone therapy and/or calcium and Vitamin D supplementation (Table 4). The adjusted difference in 3-year hip BMD according to baseline PPI use was 0.74% (95% CI, 0.01 to 1.51), favoring non-use. We did not observe a significant difference in 3-year change in BMD at the spine or total body. Lastly, using a repeated measures model to examine change in BMD from baseline for participants at years 3 and 6, we found that the hip BMD significantly differed between PPI users and non-users over time (p=.001) while spine and total BMD did not (p=0.34, 0.38, respectively, Figure 1). Repeating this analysis using actual BMD, rather than percent change from baseline yielded similar results (hip p=.04, spine p=0.28 and whole body p=0.81). When a time-dependent PPI use variable was used (including year 3), the difference in hip BMD was no longer significant (p= 0.43).

Figure 1.

PPI Use and Bone Mineral Density at Hip, Spine, and Total Body

Discussion

In this large prospective population-based study of postmenopausal women without history of hip fracture, PPI use was not significantly associated with increased hazard of incident hip fracture. Among PPI users at baseline, the hazard ratio for hip fracture was 1.00 and the confidence intervals indicate that the true hazard ratio may be as high as 1.40 or as low as 0.71. An increased risk for hip fracture was not noted with longer duration of PPI use nor in any subgroup of women classified by age, BMI, current hormone use, calcium intake or history of non-hip fracture. However, we did find that baseline PPI use was associated with an increased risk for other fracture outcomes, including clinical spine, lower wrist/arm and total fractures. The effect size was reduced for these latter fracture outcomes when a time-varying exposure was considered.

Several large epidemiological evaluations suggest that use of PPIs is associated with increased risk for osteoporotic fractures.3–6 In a nested case-control study conducted in a British sample using the General Practice Research Database, PPI use of at least 1 year was associated with a 44% increase in hip fracture, with a greater risk in men and with higher doses.4 However, a second analysis of the same database by other researchers using different epidemiologic methods did not find an association with PPI use and hip fracture.7 In a case-control study in a Canadian sample using administrative claims data, 7 or more years of PPI use was associated with a 92% increase in risk for any osteoporotic fracture and 5 or more years of use was associated with a 62% increase for hip fracture; shorter durations of use did not significantly increase risk.5 In the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, self-reported use of PPIs was associated with a 34% increased risk for nonspine fractures and 16% increased risk for hip fracture, the latter had confidence intervals that included one. The authors noted that the limited number of hip fractures may have precluded finding an association.6 Unlike other studies,4, 5 we did not observe an increased fracture risk with longer duration of use, however few women had durations of use that exceeded 3 years.

Baseline BMD did not vary at any site according to PPI use nor according to duration of baseline PPI use. The adjusted difference in 3-year hip BMD according to baseline PPI use was 0.74% (95% CI, 0.01 to1.51), marginally favoring non-use. However, this association was not present after examining longer follow-up to 6 years and including time-dependent PPI use (year 3). We did not observe an association with baseline PPI use with 3-year BMD change at the spine or total body. PPI use was not related to bone loss in two cohorts of men and women with 4.6 to 4.9 years of follow-up.6

Interestingly, the increased risk for total fractures with PPI use was not mitigated by use of high calcium supplementation. Given the hypothesis that reduced calcium absorption with long-term PPI therapy may mediate the increased fracture risk, we might expect effect modification by baseline calcium intake. It is not clear why women without prevalent non-hip fractures, or those younger than age 70 were at greater risk for total fractures with PPI use. Perhaps PPI use is a risk factor in those at low risk for fractures, whereas other established risk factors for fractures are more important and dampen any potential risk of PPI use in those with established risk factors (such as history of fracture). This finding is in direct contrast to a study reporting that PPI use did not increase risk of hip fractures in a sample of women without known risk factors.7 These findings require confirmation.

The mechanism by which long term PPI use may increase fractures is unknown, but is postulated to be related to profound acid-suppressive effects that may reduce intestinal calcium absorption eventually leading to bone resorption. However, the role of gastric pH in calcium absorption is controversial.18 Calcium absorption is highly variable and is dependent on several factors including vitamin D status, total daily intake, dose, and concurrent food intake. Data are limited with regards to the effect of PPI use on calcium absorption with conflicting results.19–23 Using an indirect measure of calcium absorption, short term studies in healthy men19 and dialysis patients20, 21 indicate that omeprazole treatment blunted the rise in serum calcium following a test meal, suggesting reduced calcium absorption. In contrast, a study using a direct measure of intestinal calcium absorption found that omeprazole did not reduce calcium absorption in healthy individuals.22 Conversely, PPI therapy may have a positive effect on bone through inhibition of the osteoclastic proton transport system leading to reduced bone resorption.24–26 This direct effect on bone could counteract the potential negative impact of calcium malabsorption.

Strengths of the present study include the large sample size, diversity of participants, the adjudication of hip fractures, the large number of fracture events, the availability of data on numerous confounding factors not available in past investigations (including calcium intake), and the ability to assess associations with bone mineral density and fracture in the same study. Because of these strengths, we have been able to extend the findings from past investigations; however, our study as several limitations. PPI users had more chronic health conditions (including osteoporosis) and risk factors for fractures (e.g. older age, history of nonhip fracture). We did our best to adjust for these baseline differences, but like all observational studies, residual or unmeasured confounding could explain increased associations for some fracture types. We had relatively low prevalence of PPI use in the study sample, particularly long-term PPI use. We could not account for PPIs used in the past that were no longer being taken at baseline. Lack of information on dose of PPI medication was another limitation, although the available data did allow examination of duration. Reliance on self-report of nonhip clinical fractures in the Observational Study component is a third limitation, however, sensitivity analyses using only adjudicated fractures from WHI CT confirmed the self-report findings, particularly for spine and total fractures. Furthermore, spine radiographs were not obtained, so we could not examine associations with subclinical spine fractures.

In summary, PPI use was not associated with hip fractures, but was associated with clinical spine, arm/wrist and total clinical fractures. A robust association of PPI use with BMD was also not found. Questions remain regarding the potential risk associated with long-term PPI use and fracture risk, thus based on the accumulation of evidence, it is prudent for clinicians to periodically re-evaluate the need for long-term PPI therapy. For those older adults who do require long-term PPI therapy, it is reasonable to focus on using the lowest effective dose, ensuring adequate dietary calcium intake and adding calcium supplements when necessary

Acknowledgement

Shelly Gray and Andrea LaCroix had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding/Support: The WHI Program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of Health, US Public Health Service contract N01-WH-3-2118. The NIH Project Office reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None

References

- 1.2008 Top 200 generic drugs by total prescriptions. Drug Topics. 2009 May 26;:4–6. Accessed at http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/data/articlestandard/drugtopics/192009/597084/article.pdf on 17 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.2008 Top 200 branded drugs by total prescriptions. Drug Topics. 2009 May 26;:10–12. Drug Topics. Accessed at http://drugtopics.modernmedicine.com/drugtopics/data/articlestandard//drugtopics/222009/599845/article.pdf on 17 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Fracture risk associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetylsalicylic acid, and acetaminophen and the effects of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;79:84–94. doi: 10.1007/s00223-006-0020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006;296:2947–2953. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Targownik LE, Lix LM, Metge CJ, Prior HJ, Leung S, Leslie WD. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008;179:319–326. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu EW, Blackwell T, Ensrud KE, et al. Acid-suppressive medications and risk of bone loss and fracture in older adults. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;83:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9170-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaye JA, Jick H. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of hip fractures in patients without major risk factors. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:951–959. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.8.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grisso JA, Chiu GY, Maislin G, Steinmann WC, Portale J. Risk factors for hip fractures in men: a preliminary study. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6:865–868. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650060812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Human Services. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2004 Accessed at http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/bonehealth/content.html on 17 June 2009. [PubMed]

- 10.Langer RD, White E, Lewis CE, Kotchen JM, Hendrix SL, Trevisan M. The women's health initiative observational study: baseline characteristics of participants and reliability of baseline measures. Ann of Epidemiol. 2003;13(Supplement 1):S107–S121. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Design of the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. The Women's Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Z, Kooperberg C, Pettinger MB, et al. Validity of self-report for fractures among a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women: results from the Women's Health Initiative observational study and clinical trials. Menopause. 2004;11:264–274. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000094210.15096.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DXA Quality Assurance. Accessed at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/deca/whios/studydoc/procedur/bone/1.pdf. on 6 July 2009.

- 14.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, et al. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kristal AR, Feng Z, Coates RJ, Oberman A, George V. Associations of race/ethnicity, education, and dietary intervention with the validity and reliability of a food frequency questionnaire: the Women's Health Trial Feasibility Study in Minority Populations. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:856–869. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins J, Aragaki AK, Kooperberg C, et al. Factors Associated With 5-Year Risk of Hip Fracture in Postmenopausal Women. JAMA. 2007;298:2389–2398. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bo-Linn GW, Davis GR, Buddrus DJ, Morawski SG, Santa Ana C, Fordtran JS. An evaluation of the importance of gastric acid secretion in the absorption of dietary calcium. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:640–647. doi: 10.1172/JCI111254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graziani G, Como G, Badalamenti S, et al. Effect of gastric acid secretion on intestinal phosphate and calcium absorption in normal subjects. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:1376–1380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graziani G, Badalamenti S, Como G, et al. Calcium and phosphate plasma levels in dialysis patients after dietary Ca-P overload. Role of gastric acid secretion. Nephron. 2002;91:474–479. doi: 10.1159/000064290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardy P, Sechet A, Hottelart C, et al. Inhibition of gastric secretion by omeprazole and efficiency of calcium carbonate on the control of hyperphosphatemia in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Artif Organs. 1998;22:569–573. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.1998.06200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serfaty-Lacrosniere C, Wood RJ, Voytko D, et al. Hypochlorhydria from short-term omeprazole treatment does not inhibit intestinal absorption of calcium, phosphorus, magnesium or zinc from food in humans. J Am Coll Nutr. 1995;14:364–368. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1995.10718522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connell MB, Madden DM, Murray AM, Heaney RP, Kerzner LJ. Effects of proton pump inhibitors on calcium carbonate absorption in women: a randomized crossover trial. Am J Med. 2005;118:778–781. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farina C, Gagliardi S. Selective inhibition of osteoclast vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:2033–2048. doi: 10.2174/1381612023393369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuukkanen J, Vaananen HK. Omeprazole, a specific inhibitor of H+-K+-ATPase, inhibits bone resorption in vitro. Calcif Tissue Int. 1986;38:123–125. doi: 10.1007/BF02556841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizunashi K, Furukawa Y, Katano K, Abe K. Effect of omeprazole, an inhibitor of H+,K(+)-ATPase, on bone resorption in humans. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;53:21–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01352010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]