Abstract

BACKGROUND: This is a follow up to a study done at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH) 11 years ago on the management of prostate cancer.

AIMS: To assess the current pattern in the management of prostate cancer in Port Harcourt, Nigeria and the impact of changes in diagnosis and treatment.

METHODS: All the case notes of prostate cancer presenting in the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital between January 2003 and December 2012 were reviewed. Data on demography, clinical presentations, co-morbidities, investigations, treatment, complications and outcome of treatment were extracted and analyzed using SPSS 20.0 0

RESULTS: A total of 294 histologically confirmed patients with cancer of the prostate were treated within the study period. Out of these, 216 (73.5%) case notes were analysed. The mean age was 69.9 years (51 -90 years). All the patients had lower urinary tract symptoms, 30 (14.0%) had haematuria while 19(8.8%) presented with paraplegia. The prostate specific antigen (PSA) ranged from 0.5 - 760ng/ml. Two hundred and five (95%) received androgen deprivation therapy. Of these, 123 (60%) had bilateral subcapsular orchidectomy and anti androgen, 3 (1.4%) had abiraterone. Five (2.3%) had radical prostatectomy, 22 (10.2%) had chemotherapy while 16(7.4%) had radiotherapy. Seventy-two (33.5%) died within 2 years of diagnosis while 49(30.2%) survived more than 5 years.

CONCLUSION: There is rising prevalence of carcinoma of the prostate in this centre. Many patients presented late. There has been expansion in diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities with attendant improvement in patients’ survival. Co-morbidities adversely affected the outcome of treatment.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Radical prostatectomy , Androgen deprivation therapy, Port-Harcourt , Nigeria

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the leading cause of morbidity among aging men1. It is the leading cause of cancer-related death in men 40 years and above2,3. While the disease has low prevalence in South East Asia, high rates have been reported in men of African descent4,5. Variation exists in incidence rates even within Africa2,6.

There have been recent advances in the scope of diagnostic and therapeutic measures targeted at the improvement in the management of prostate cancer. The advent of prostate specific antigen (PSA) has made a significant impact on diagnosis and treatment of the disease. Various imaging techniques are available for staging cancer of the prostate7,8. Radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy have led to successful treatment of early stages of the disease9,10. Newer modalities of treatment are also available for advanced disease10,11. In spite of these treatment modalities, a new complication of treatment, castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) has emerged. These patients have lost the ability to respond to medical or surgical castration.

University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH) is the major tertiary hospital serving the Rivers State and the adjourning Southern Nigerian states of Imo, Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Delta and Abia. The hospital receives patients from public and private health facilities within these states. A study conducted in Port Harcourt in 2002 reported our experience in the pre-PSA era12. It reported the clinical features and outcome of treatment of prostate cancer. In this PSA era, the scope of diagnostic and therapeutic armamentaria has expanded. Public awareness campaigns on the radio and television have become regular features in Rivers State. We hereby report a retrospective review of the current pattern in the diagnosis, treatment and outcome of treatment of prostate cancer in Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

Materials

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective study of all patients with histologically confirmed prostate cancer managed at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH) over ten years (2003-2012).

The total number of adult men coming to UPTH was obtained from the Medical records department of the Hospital. The case notes of those with histologically confirmed cancer of the prostate were retrieved from the Medical Records Department, outpatient clinics, ward and theatre registers for this study. Information about biodata, clinical features, treatment administered and outcome of treatment were extracted.

Clinical evaluation of the patients included a history of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), digital rectal examination (DRE), serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) estimation, and transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) of the prostate. Where DRE, PSA and or TRUS suggested features of cancer of the prostate, digitally-guided Tru-CutR needle biopsy of the prostate was carried out. Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole were administered orally as prophylaxis against infection. Chest X-ray, ECG, full blood count, serum electrolytes, urea, creatinine and lumbosacral spine X-ray were evaluated for each patient. CT-scan of the abdomen, isotope bone scan, MRI of the pelvis and other investigations were carried out as indicated.

The mode of treatment was assigned to each patient based on clinical Stage determined by a combination the PSA, DRE, histopathological grade and radiological findings. The age of the patients, presence of co-morbidities, and patients’ choice were also taken into consideration. Early stage disease was treated by radical prostatectomy or radical radiotherapy/ brachytherapy. Late stages were treated by androgen deprivation therapy using either bilateral orchidectomy or gonadotrophin releasing hormone agonist or antagonist. Some patients also had anti-androgens using bicalutamide, flutamide, or cypoterone acetate. Castration resistant cases were treated with low dose diethyl stilbesterol, steroids, Ketoconazole, chemotherapy and abiraterone as indicated. Patients with bony metastasis received external beam radiotherapy and biphosphonates.

The outcomes of treatment were judged by clinical improvement in symptoms and by laboratory profiles. The patients were followed up at the outpatient clinics. The patients who died within the study period were noted. The intervals between presentation and death were recorded for those dead. The patients alive for 5 years from time of diagnosis to time of study were subjected to further statistical analysis to determine the effect of age, PSA value, co-morbidities, Gleason score and type of treatment on patients’ survival.

The data obtained from these records were analysed using SPSS version 20.00 and presented as charts, tables and figures.

Reports

RESULTS

From the records, 517,241 adult men were treated in UPTH within the study period. A total of 294 patients had histologically confirmed diagnosis of cancer of the prostate. Out of the 294, case notes of 216 (73.5%) patients were available for analysis. The mean age was 69.9 years (51 – 90) years. Of the 216 analyzed, 154 (72%) were within age group 60 – 79 years. Two patients were aged 90 years, while 25 (11.6%) were aged less than 60 years. The age distribution is shown in Table 1.

The mode of presentation is shown in Table 2. All patients presented with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), 30 (13.9%) presented with haematuria, while 19 (8.8%), 10 (4.6%), 10 (4.6%) and 6 (2.8%) also had paraplegia, acute urine retention, anaemia and bone pain respectively. Ten patients presented as incidental prostate cancer. These 10 patients had clinical and laboratory features suggestive of benign prostatic enlargement but histology from the specimens was reported as prostate cancer. One hundred and twenty two patients (56.48%) did not present with any complications.

Among the 216 study patients, 106 (49.1%) had associated co-morbidities as shown in Table 3. Of these co-morbidities, hypertension was seen in 78 (73.3%) patients, 8 (7.5%) patients had diabetes mellitus and 4 (3.7%) had both hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Five (4.7%) had congestive cardiac failure, 3 (2.8%) had chronic renal failure and 8 (7.5%) had other morbidities such as inguinal hernia, arthritis, haemorrhoids and hydrocoele.

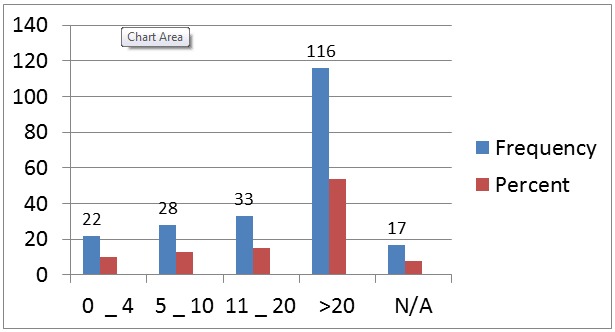

The PSA ranged from 0.5 to 760 ng/ml. All the patients had transrectal ultrasound scan of the prostate. Only 20 patients had PSA less than 4ng/ml. Most of the patients had PSA values more than 20ng/ml; the PSA values are as shown in Figure 1.

Twenty (9.3%) patients had isotope bone scan for suspected metastatic bone disease. Patients for bone scan were referred to University College Hospital Ibadan or National Hospital Abuja for the tests. MRI of the pelvis was carried out in 11 patients, while abdominal CT scan was done on 8 patients. Analysis of the histological patterns revealed that 40 patients (18.5%), 23 (10.6%) and 22 (10.2%) were diagnosed as well, moderately and poorly differentiated carcinoma of the prostate respectively. One hundred and thirty one patients (60.6%) were reported as adenocarcinoma without indicating the degree of differentiation.

Regarding the Gleason scores of these patients’ histological specimens, 77 (35%) had Gleason score recorded. Of the 77, 2 (2.6%) had Gleason score 2-4, 43 (55.8%) had Gleason score 5-7 while 32 (41.6%) had Gleason score 8-10.

Twelve (5.6%) patients had curative treatment: 5 (2.3%) had radical prostatectomy (1 had laparoscopic radical prostatectomy outside Nigeria), 5 (2.3%) had radical radiotherapy in India, while 2 had brachytherapy in South Africa. In addition, 9 (4.2%) patients had palliative radiotherapy at the National Hospital, Abuja and Eko Hospital, Lagos while 22 (10.2%) had chemotherapy for metastatic disease using docetaxel.

Two hundred and five (95%) out of 216 had androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Out of these, 123 (60%) had both bilateral subcapsular orchidectomy and anti androgen (Flutamide or Bicalutamide) while 18 (8.8%) and 17 (8.3%) had bilateral subcapsular orchidectomy (BSO) and anti-androgen alone respectively as shown in Table 4. Twenty nine patients (14.1%) had luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist (Zoladex and leuporellin) and anti-androgen, 15 (7.3%) had LHRH agonist alone and 1 (0.4%) had LHRH antagonist (degarelix). Forty three (19.9%) patients of the 216 developed castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Among the CRPC patients, 14 (6.5%) received diethylstilboesterol, 9(4.2%) had additional radiotherapy, 22 (10.2%) had chemotherapy and 3 (1.4 %) had abiraterone.

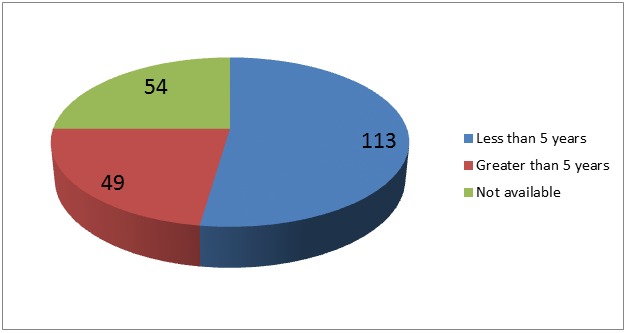

Figure 2 shows the survival pattern for the patients. Among those who survived, 113 (69.8%) had less than five year overall survival and 49 (30.2%) had greater than five year overall survival. Results of survival in 54 patients (25%) patients were not available. Seventy-two patients (33.2%) died within 2 years of diagnosis and treatment. There was no correlation between age or PSA level at presentation and survival. However, 75 patients with co-morbidity survived less than 5 years, while 31 of them survived more than 5 years. Using Levene’s test for equality of variance, there is correlation between absence of co-morbidity and survival beyond 5 years. But it was not statistically significant (P value= 0.065).

Discussion

The cause of prostate cancer is not known. Several genetic and environmental risk factors have been recognized13,14. Life style factors have also been reported to have impact on the risk associated with prostate cancer15. Biological differences in tumorogenesis may be a factor in the course of the disease among different races16. It has been suggested that the heterogeneity of genes expression patterns is responsible for the attendant disparity in incidence and aggressiveness of prostate cancer13,17.

The stage at diagnosis, tumour aggressiveness and treatment modality affect the outcome of treatment. Caucasian men have been reported to have better survivals than men of African descent 7. Unrecognized interactions of host and environmental factors have been suggested to contribute to differential survival outcomes by races in gender-specific malignancies like prostate cancer18. It will be necessary to study the impact of the expansion of our diagnostic and therapeutic abilities on the management of cancer of the prostate.

Prostate cancer is common in the developed world, with increasing rates in developing world 19. The burden of prostate cancer among adult males of Port Harcourt has been reported to be high 20. Unlike South East Asia and some parts of Europe where low incident rates have been reported, a previous report suggested a high prevalence in Nigeria 21. In our previous study 12, we reported a hospital prevalence of 114/100,000 among men 40 years and above. It is now accepted that there is high prevalence of prostate cancer in Nigeria 2,12.The observed high incidence among Nigerians and other men of African origin can be attributed to a host of genetic and environmental factors 13,15,17.

The number of patients diagnosed with prostate cancer in this study was 294. This is almost double our previous report of 177 within the same interval of ten years12. This may be explained by the fact that we now carry out public enlightenment campaigns on Radio and Television as well as PSA evaluation for patients with suspected cancer of the prostate, and to a limited extent screening. Whether this is a true rise in incidence or better diagnostic capability cannot truly be determined as no previous population based epidemiological study has been carried out in our centre. A rising incidence of cancer of the prostate has also been reported in other studies in Nigeria, Asia, Europe and America 4,7,22,23. These authors attributed the rise mainly to increased surveillance, especially with PSA screening.

Prostate cancer tends to develop in men over the age of 50 years 24, old age being a risk factor for cancer of the prostate2. The mean age of patients in this study was 69.9 years, with 88.4% of the patients aged between 60 and 80 years. This confirms the assertion that prostate cancer is strongly related to aging. This was similar to our previous report of 71.6 years and 71.4 years reported by Ogunbiyi in Ibadan2,12.

Prostate cancer has diverse modes of presentation. It may be asymptomatic or symptomatic. It has also been known to be incidental, occult or latent. While early prostate cancer may be asymptomatic, others may present with lower urinary tract symptoms. Miller and colleagues reported that a third of their patients were asymptomatic while two thirds had symptoms at presentation8. Late presentation has been reported among Nigerian men with prostate cancer 2,12,25. In the present study, all the patients had lower urinary tract symptoms(LUTS), a feature of late presentation. In addition, 34.5% presented with complications such as urinary retention, haematuria, renal failure and recurrent urinary tract infection. This late presentation is the pattern in most African countries and among African Americans6,25. Factors associated with late presentation include ignorance, poor health seeking behaviour, lack of routine medical checkups, superstition and wrong assumption that lower urinary tract symptoms are part of normal aging process6,25.

Prostate specific antigen (PSA) estimation has made an impact in the screening, diagnosis, and prognostication and monitoring of treatment of prostate cancer26. Although PSA is not 100% specific or sensitive, it has an important role in management of prostate cancer 27. In our previous report12, as in Maiduguri in 20066, PSA evaluation was not available. Most of the patients in this study presented with initial PSA levels of more than 20ng/ml. Catalona et al 28 found that over half of the patients with PSA values more that 10ng/m had advanced CaP. Extrapolated, this implies that most of our patients presented late with advanced disease.

One of the variables on which risk-stratification for prostate cancer mortality is based is histological pattern of the disease29. In the previous study, all the 57.4% that had records of histology were diagnosed as adenocarcinoma. This was similar to reports from Calabar, Nigeria 25. In this study, the degree of differentiation was documented in only 44.9% of the biopsies. Among these, most were either well or moderately differentiated

The risk stratification of mortality from cancer of the prostate can be assessed by the Gleason grading system. Gleason grading / scoring system was not available in our centre until recently. The histological pattern of the biopsy specimen revealed that 41.6% of the patients had high scores ≥ 8. This is similar to the pattern in the reports from other Nigerian centres 25,30. Chaux et al reported that the presence of Gleason score ≥ 8 is associated with increased incidence of extraprostatic extension of cancer of the prostate31. This suggests that most of the cancer of the prostate in this study were of the aggressive variant. However, most of the specimens were from Tru –cutR needle biopsies. It has been reported that Gleason scores from prostatectomy samples are more accurate than needle biopsies31,32. According to Stav et al, pre-operative needle biopsies undergraded the Gleason scores in 41% of patients who had radical prostatectomy32.

Prostate cancer is a disease of aging men, who often have co-morbidities. In this study, co-morbidities were recorded in 106(49%) patients. The most common co-morbidities were hypertension, diabetes, congestive cardiac failure, chronic renal failure, obesity, and erectile dysfunction. These co-morbidities have been reported elsewhere30,33. Most of these diseases are age-related. Also some patients presented with similar conditions due to complication of androgen deprivation therapy. Androgen deprivation leads to increased bone resorption and therefore the possibility of osteoporosis34. Testosterone is involved in gluconeogenesis. Absence of testosterone affects insulin response, thereby giving rise to diabetes mellitus. Cardiovascular diseases, dyslipidaemia and diabetes mellitus which are known complications of ADT may be part of the metabolic syndrome associated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)34,35.

Curative management of cancer of the prostate is possible if diagnosis is made early. Palliative treatment is administered to those diagnosed late with advanced disease. In our previous study, all the patients presented late and they were treated with androgen deprivation therapy, principally orchidectomy. A few of those patients had diethylstilbesterol12. In the present study, most of the patients also presented with advanced disease and were treated with androgen deprivation. However, our scope of ADT has expanded. Some had LHRH receptor agonists (goserelin and leuporellin), one patient was treated with degarelix, a LHRH antagonist. These are standard treatments for advanced cancer of the prostate as reported by others 34,36. Some of the patients in this study had palliative radiotherapy as an adjunct therapy for locally advanced disease or for bony metastasis as reported earlier10.

In this study, 12 patients presented early as staged by low PSA levels and organ confinement on MRI/isotope bone scan. They were treated with radical prostatectomy (RP), radical radiotherapy or brachytherapy. Four of the radical prostatectomies were done in our centre by the open retropubic approach, one by laparoscopic radical prostatectomy in USA. The patients who had radical radiotherapy and brachytherapy were treated in India and South Africa respectively. These patients are still alive. However they have been followed up for only one to four years. These methods of treatment are established methods for low-risk, early stage disease 29,37.

Castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) is a major challenge in patients who have advanced disease following relapse after treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). The first line of management in this series was either addition of anti-androgen if not added at the onset or intermittent total androgen blockade. Some of the patients were also managed with addition of steroids, low dose stilboesterol and ketoconazole. This has been recommended treatment for castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) elsewhere11.

Chemotherapy was also used with limited success in 22 of these patients. The therapy included docetaxel with steroids at 3 weekly intervals for 6 weeks based on patient’s tolerability. Two of the patients are currently on abiraterone for CRPC. Others have reported the use of these chemotherapeutic agents37-39. In the short term, there was reduction in PSA level as well as some clinical improvement. However, these drugs were sourced at prohibitive costs.

In our previous report, most of the patients died within 2 years of diagnosis12. Presently 90 (41.7%) patients are alive after 2 years and only 49 (30.2%) patients of the 162 whose survival records were documented were alive after 5 years. This is an improvement in outcome of management compared to the previous decade. The improvement can be explained by the expanded scope of available diagnostic and therapeutic options.

Many factors have been linked to the survival of patients with cancer of the prostate. Postulated factors include race, age at diagnosis, aggressiveness of tumors, tumour stage at diagnosis and presence of co-morbidities37,39. When we compared our patients’ 5- year-survival outcomes with PSA levels at diagnosis, age of patients, treatment and presence of co-morbidity, there was only a marginal difference between outcome and presence of co-morbidities. Many patients may have died from the co-morbidities and not the cancer. Many years ago, it was believed that patients with prostate cancer did not die from it but with it40. The actual cause of death in the patients was not determined because, for cultural reasons, the autopsy acceptance rate in this part of Nigeria is very low.

One challenge encountered with a retrospective study such as this was poor record keeping. In the present study we now have the ability to carry out PSA estimation, CT Scan, MRI, and on referral basis, isotope bone scan. These facilities improved the diagnostic and staging ability in the management of the disease. Unlike in our previous study, curative treatment is now available for early cancer of the prostate and there is a wider spectrum of treatment options for advanced cancer of the prostate.

Conclusions

There is an increase in the incidence of cancer of the prostate due to increased diagnostic ability. Many patients still presented at advanced stage of the disease, principally due to ignorance. There have been notable expansions in the scope of our diagnostic and therapeutic options with attendant improvement in survival of patients. The presence of co-morbidities adversely affected the survival of patients with prostate cancer. Public enlightenment and routine screening of population at risk can help to detect early cases so that appropriate curative intervention can be applied. Provision of additional equipment and training of personnel will provide the needed skill to tackle the enormous problem of cancer of the prostate in our region.

Table 1: Age distribution of patients with prostate cancer

| Age Group (years) | Frequency | Percent |

| 50-59 | 25 | 11.6 |

| 60-69 | 80 | 37.4 |

| 70-79 | 74 | 34.6 |

| 80-89 | 35 | 16.4 |

| >90 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Total | 216 | 100 |

Table 2: Presenting symptoms in patients with prostate cancer

| Symptoms | Frequency | Percent |

| Haematuria | 30 | 13.9 |

| Acute urine retention | 10 | 4.6 |

| Chronic urine retention | 6 | 2.8 |

| Paraplegia | 19 | 8.8 |

| Anaemia | 10 | 4.6 |

| CVD | 3 | 1.4 |

| Bone pain | 6 | 2.8 |

| Others | 10 | 4.6 |

| None | 122 | 56.5 |

| Total | 216 | 100 |

Table 3: Associated co-morbidity in prostate cancer patients

| Co-morbidity | Frequency | Percent |

| Hypertension | 78 | 73.5 |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) | 8 | 7.5 |

| Hypertension and DM | 4 | 3.7 |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 5 | 4.7 |

| Chronic renal failure | 3 | 2.8 |

| Others | 8 | 7.5 |

| Total | 106 | 100 |

Table 4: Androgen deprivation therapy offered to the prostate cancer patients

| Androgen deprivation therapy | Frequency | Percent |

| BSO alone | 18 | 8.8 |

| BSO and anti androgen | 123 | 60 |

| LHRH antagonist | 17 | 8.3 |

| Anti androgen alone | 1 | 0.4 |

| LHRH agonist | 15 | 7.3 |

| LHRH agonist and anti androgen | 28 | 13.7 |

| Abiraterone | 3 | 1.5 |

| Total | 205 | 100 |

| BSO = Bilateral subcapsular orchidectomy LHRH = Leuteinizing hormone releasing hormone | ||

Figure 1.

Frequency of Prostate-specific antigen (ng/ml) in 216 prostate cancer patients

Figure 2.

Overall survival in 216 patients with prostate cancer

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Grant support: None

References

- 1.Delongchamps NB, Singh A, Haas GP. Epidemiology of prostate cancer in Africa: another step in the understanding of the disease? Curr Probl Cancer. 2007;31:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogunbiyi JO, Shittu OB. Increased incidence of prostate cancer in Nigerians. J Natl Med Assoc. 1999;91:159–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams H. Epidemiology, pathology, and genetics of prostate cancer among African Americans compared with other ethnicities. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:439–453. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sim HG, Cheng CW. Changing demography of prostate cancer in Asia. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:834–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moul JW. Targeted screening for prostate cancer in African-American men. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2000;3:248–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yawe KT, Tahir MB, Naggada HA. Prostate cancer in Maiduguri. West Afr J Med. 2006;25:298–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajape AA, Ibrahim KO, Fakeye JA, Abiola OO. An overview of cancer of the prostate diagnosis and management in Nigeria: the experience in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Ann Afr Med. 2010;9:113–117. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.68353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller DC, Hafez KS, Stewart A, Montie JE, Wei JT. Prostate carcinoma presentation, diagnosis, and staging: an update forms the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2003;98:1169–1178. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulson DF, Moul JW, Walther PJ. Radical prostatectomy for clinical stage T1-2N0M0 prostatic adenocarcinoma: long-term results. J Urol. 1990;144:1180–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39686-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hindson B, Turner S, Do V. Palliative radiation therapy for localized prostate symptoms in hormone refractory prostate cancer. Australas Radiol. 2007;51:584–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2007.01897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acar O, Esen T, Lack NA. New therapeutics to treat castrate-resistant prostate cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/379641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eke N, Sapira MK. Prostate cancer in Port Harcourt, Nigeria: features and outcome. Niger J Surg Res. 2002;4:34–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caruso RP, Levinson B, Melamed J, Wieczorek R, Taneja S, Polsky D, Chang C, al et. Altered N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 protein expression in African American compared with Caucasian prostate cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:222–227. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0604-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albain KS, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Hershman JR. Racial disparities in cancer survival among randomized clinical trials patients of the Southwest Oncology Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:984–992. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkateswaran V, Klotz LH. Diet and prostate cancer: mechanisms of action and implications for chemoprevention. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:442–453. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pettaway CA, Song R, Wang X, Sanchez-Ortiz R, Spiess PE, Strom S, Troncoso P. The ratio of matrix metalloproteinase to E-cadherin expression: A pilot study to assess mRNA and protein expression among African American prostate cancer patients. Prostate. 2008;68:1467–1476. doi: 10.1002/pros.20812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrell J., Petrovics G., McLeod D.G., Srivastava S. Genetic and Molecular Differences in Prostate Carcinogenesis between African American and Caucasian American Men. Int J Mol Sci. 2013:15510–15531. doi: 10.3390/ijms140815510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godwin O.I., Fisseha A, Godwin AA. Emergent trends in the reported incidence of prostate cancer in Nigeria. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:19–32. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S23536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baade PD, Youlden DR, Krnjacki LJ. International epidemiology of prostate cancer: geographical distribution and secular trends. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009;53:171–184. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sapira MK, Obiorah CC. Age and pathology of prostate cancer in South-Southern Nigeria; is there a pattern? Med J Malaysia . 2012;67:417–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osegbe DN. Prostate cancer in Nigerians: facts and non facts. J Urol. 1997;157:1340–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsing A.W., Tsao L, Devesa SS. International trends and patterns of prostate cancer incidence and mortality. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:60–67. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000101)85:1<60::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potosky AL, Miller BA, Albertsen PC, Kramer BS. The role of increasing detection in the rising incidence of prostate cancer. JAMA. 1995;273:548–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegel R DeSantis,, Virgo K., Stein K., Mariotto A., Smith T., Cooper D., et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ugare UG, Bassey IE, Jibrin PG, Ekanem IA. Analysis of Gleason grade and scores in 90 Nigerian Africans with prostate cancer during the period 1994 to 2004. Afr Health Sci. 2012;12:69–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aghaji AE, Odoemene CA. Prostate cancer after prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia in Nigera. East Afr Med Journal. 2000;77:635–639. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson IM, Pauler DK, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lucia MS, Parnes HL, Minasian LM, et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level < or =4.0 ng per milliliter. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2239–2246. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catalona WJ, Hudson MA, Scardino PT, Richie JP, Ahmann FR, Flanigan RC, deKernion JB, Ratliff TL, Kavoussi LR, Dalkin BL, et al. Selection of optimal prostate specific antigen cutoffs for early detection of prostate cancer: receiver operating characteristic curves. J Urology. 1994;152(6.1):2037–2042. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou P, Chen MH, McLeod D, Carroll PR, Moul JW, D'Amico AV. Predictors of prostate cancer-specific mortality after radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6992–6998. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adewuyi SA, Mbibu NH, Samaila MO, Ketiku KK, Durosinmi-Etti FA. Clinico-pathologic characterisation of metastatic prostate cancer in the Radiotherapy and Oncology Department, Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Zaria - Nigeria: 2006 - 2009. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2013;20:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaux A, Fajardo DA, Gonzalez-Roibon N, Partin AW, Eisenberger M, DeWeese TL, Netto GJ. High-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma present in a single biopsy core is associated with increased extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and positive surgical margins at prostatectomy. Urology. 2012;79(863):868. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stav K, Judith S, Merald H, Leibovici D, Lindner A, Zisman A. Does prostate biopsy Gleason score accurately express the biologic features of prostate cancer? Urol Oncol. 2007;25:383–386. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sapira Mk, Onwuchekwa AC, Onwuchekwa CR. Co-morbid medical conditions and medical complications of prostate cancer in Southern Nigeria. Med J Malaysia. 2012;67:412–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raynaud JP. Testosterone deficiency syndrome: treatment and cancer risk. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;114:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basaria S. Androgen deprivation therapy, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular mortality: an inconvenient truth. J Androl. 2008;29:534–539. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.005454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Safriadi F. Bone metastases and bone loss medical treatment in prostate cancer patients. Acta Med Indones. 2013;45:76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daskivich TJ, Fan KH, Koyama T, Albertsen PC, Goodman M, Hamilton AS, Hoffman RM, et al. Effect of age, tumor risk, and comorbidity on competing risks for survival in a U.S. population-based cohort of men with prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:709–717. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marques RB, Dits NF, Erkens-Schulze S, Weerden WM, Jenster G. Bypass mechanisms of the androgen receptor pathway in therapy-resistant prostate cancer cell models. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albertsen PC, Moore DF, Shih W, Lin Y Li. Impact of comorbidity on survival among men with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1335–1341. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kozlowski JM, Ellis WJ, Grayhack JT. Advanced prostatic carcinoma. Early versus late endocrine therapy. Urol Clin North Am . 1991;15:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]