Abstract

This study sought to evaluate FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides (FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2) as fluorescent probes for in vitro assays of integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression in tumor tissues. FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 were prepared, and their integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding affinity was determined using the displacement assay against 125I-echistatin bound to U87MG glioma cells. IC50 values of FITC-Galacto-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-RGD2 were calculated to be 28 ± 8, 32 ± 7, and 89 ± 17 nM, respectively. The integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding affinity followed a general trend: FITC-Galacto-RGD2 ∼ FITC-3P-RGD2 > FITC-RGD2. The xenografted tumor-bearing models were established by subcutaneous injection of 5 × 106 tumor cells into shoulder flank (U87MG, A549, HT29, and PC-3) or mammary fat pad (MDA-MB-435) of each athymic nude mouse. Three to six weeks after inoculation, the tumor size was 0.1–0.3 g. Tumors were harvested for integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 staining, as well as hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Six human carcinoma tissues (colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, squamous cell lung cancer, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer) were obtained from recently diagnosed cancer patients. Human carcinoma slides were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated with ethanol, and then used for integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 staining, as well as H&E staining. It was found that the tumor staining procedures with FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides were much simpler than those with the fluorescence-labeled integrin αvβ3 antibodies. Since FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 were able to co-localize with the fluorescence-labeled integrin β3 antibody, their tumor localization and tumor cell binding are integrin αvβ3-specific. Quantification of the fluorescent intensity in five xenografted tumors (U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3) and six human carcinoma tissues revealed an excellent linear relationship between the relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels determined with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and those obtained with the fluorescence-labeled anti-human integrin β3 antibody. There was also an excellent linear relationship between the tumor uptake (%ID/g) of 99mTc-3P-RGD2 (an integrin αvβ3/αvβ5-targeted radiotracer) and the relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels from the quantification of fluorescent intensity in the tumor tissues stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2. These results suggest that FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides might be useful to correlate the in vitro findings with the in vivo imaging data from an integrin αvβ3/αvβ5-targeted radiotracer. The results from this study clearly showed that the FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides (particularly FITC-3P-RGD2 and FITC-Galacto-RGD2) are useful fluorescent probes for assaying relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels in tumor tissues.

Introduction

The integrin family is a group of transmembrane glycoproteins comprised of 19 α- and 8 β-subunits that are expressed in 25 different α/β heterodimeric combinations on the cell surface.1−4 Integrins are critically important in many physiological processes, including cell attachment, proliferation, bone remodeling, and wound healing.3,4 Integrins also contribute to pathological events such as thrombosis, atherosclerosis, tumor invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis, infection by pathogenic microorganisms, and immune dysfunction.3−10 Among 25 members of the integrin family, integrin αvβ3 is studied most extensively for its role in tumor growth, progression, and angiogenesis.

Integrin αvβ3 is a receptor for extracellular matrix proteins (vitronectin, fibronectin, fibrinogen, laminin, collagen, Von Willebrand’s factor, and osteoponin) with the exposed arginine-glycine-aspartic (RGD) tripeptide sequence.1,2 Changes in the integrin αvβ3 expression levels and activation state have been well documented during tumor growth and metastasis.5,7,10 Integrin αvβ3 is expressed in low levels on the epithelial cells and mature endothelial cells, but it is highly expressed in many tumors, including osteosarcomas, glioblastomas, melanomas, and carcinomas of lung and breast.11−24 Studies show that integrin αvβ3 is overexpressed on both tumor cells and activated endothelial cells of neovasculature.11

Integrin αvβ3 on endothelial cells modulate cellular adhesion during angiogenesis, while the integrin αvβ3 on tumor cells potentiate metastasis by facilitating invasion of tumor cells across the blood vessels.19−36 It has been shown that integrin αvβ3 expression levels correlate well with the potential for metastasis and aggressiveness of tumors, including glioma, melanoma, and carcinomas of the breast and lungs.19−25 Integrin αvβ3 has been considered an interesting biological target for development of therapeutic pharmaceuticals for cancer treatment,13,36−40 and molecular imaging probes for diagnosis of rapidly growing and highly metastatic tumors.41−52

Only two integrin family members (αvβ3 and αIIBβ3) contain the β3 chain. Since integrin αIIBβ3 is expressed exclusively on the activated platelets,26,29,30 the integrin β3 expression level on tumor cells or in tumor tissues should be the same as that of integrin αvβ3. Western blotting has been used to determine the integrin αvβ3 concentration in tumor tissues,53−59 but the percentage of integrin αvβ3 recovery from tumor tissues and its activation state remained unknown. We have been using immunohistochemical (IHC) staining with anti-integrin αvβ3 monoclonal antibodies to determine the integrin αvβ3 expression levels on tumor cells (acetone-fixed or living) and in tumor tissues (acetone or methanol-fixed).60,61 It was found that the IHC staining is an excellent technique to reflect the activation state of integrin αvβ3 because only the activated endothelial cells and some tumor cells are able to bind to the integrin αvβ3 monoclonal antibody. However, the procedures for cellular and tissue staining with fluorescence-labeled anti-integrin αvβ3 antibodies are often complicated and time-consuming because they involve the blocking of nonspecific binding and the use of secondary polyclonal antibody for the fluorescence detection. In addition, integrin αvβ3 antibodies have limited stability in aqueous solution.

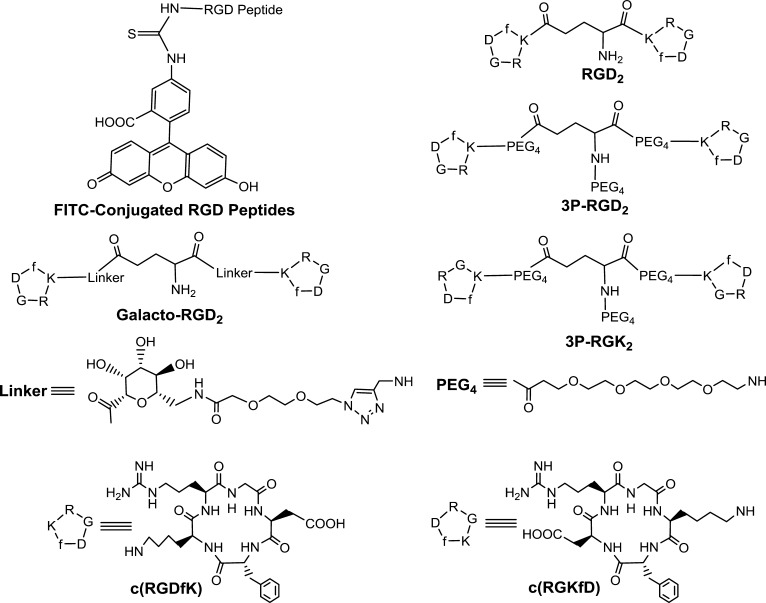

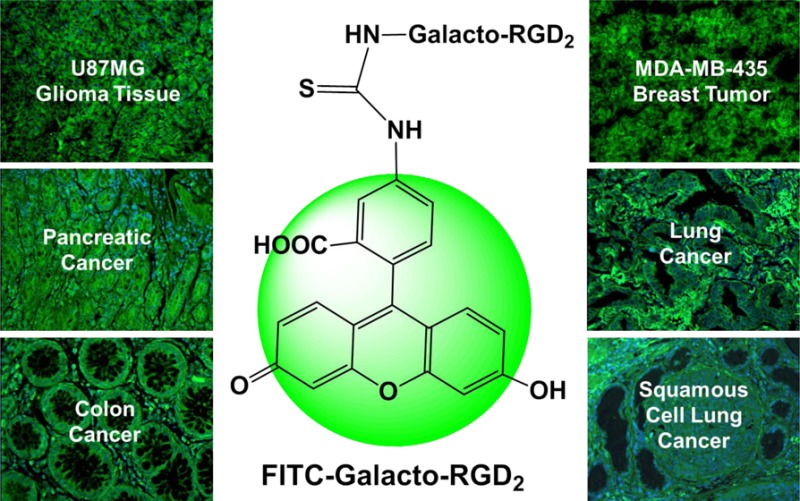

To overcome these shortcomings, we prepared three FITC conjugated dimeric cyclic RGD peptides (Figure 1): FITC-RGD2 (RGD2 = Glu[cyclo(Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Phe-Lys)]2), FITC-3P-RGD2 (3P-RGD2 = PEG4-Glu[cyclo[Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Phe-Lys(PEG4)]]2 (PEG4 = 15-amino-4,7,10,13-tetraoxapentadecanoic acid) and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (Galacto-RGD2 = Glu[cyclo[Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Phe-Lys(SAA-PEG2-(1,2,3-triazole)-1-yl-4-methylamide)]]2, SAA = 7-amino-l-glycero-l-galacto-2,6-anhydro-7-deoxyheptanamide, and PEG2 = 3,6-dioxaoctanoic acid). Since the cyclic RGD peptides, such as c(RGDfK), are antagonists for αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins,4,36−39,62 it is reasonable to believe that bioconjugates FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 will target both integrin αvβ3 and integrin αvβ5. We were interested in dimeric cyclic RGD peptides because they have significantly higher integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding affinity than their monomeric analogs.44

Figure 1.

ChemDraw structures of FITC-conjugated cyclic peptide dimers (RGD2, 3P-RGD2, 3P-RGK2, and Galacto-RGD2).

In this report, we present the evaluations of FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 as fluorescent probes to assay integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels in tumor tissues. Their integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding affinity was determined in a displacement assay against 125I-echistatin bound to U87MG glioma cells. To demonstrate their RGD-specificity, we have also prepared FITC-3P-RGK2 (3P-RGK2 = PEG4-E[PEG4-c(RGKfD)]2 = PEG4-Glu[cyclo[Arg-Gly-Lys(PEG4)-d-Phe-Asp]]2), which has the identical chemical composition to that of FITC-3P-RGD2 but with low integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding affinity due to the RGK tripeptide sequence. Even though the fluorescence-labeled cyclic RGD peptides have been reported as optical imaging probes,63 very little information is available on their validity for in vitro assays of integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression. The objective of this study is to validate the utility of FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 for determination of relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels in both the xenografted tumors and human carcinoma tissues in comparison with commercially available integrin αvβ3 monoclonal antibodies.

Results

Synthesis of FITC–Peptide Conjugates

FITC-conjugated peptides (FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGK2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2) were prepared by reacting FITC with the corresponding cyclic peptides under basic conditions in the presence of excess DIEA. All new FITC–peptide conjugates were purified by HPLC. MALDI-MS data were completely consistent with the composition proposed for FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGK2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2. Their HPLC purity was >95% before being used for the integrin αvβ3 binding assays and staining studies.

Integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 Binding Affinity

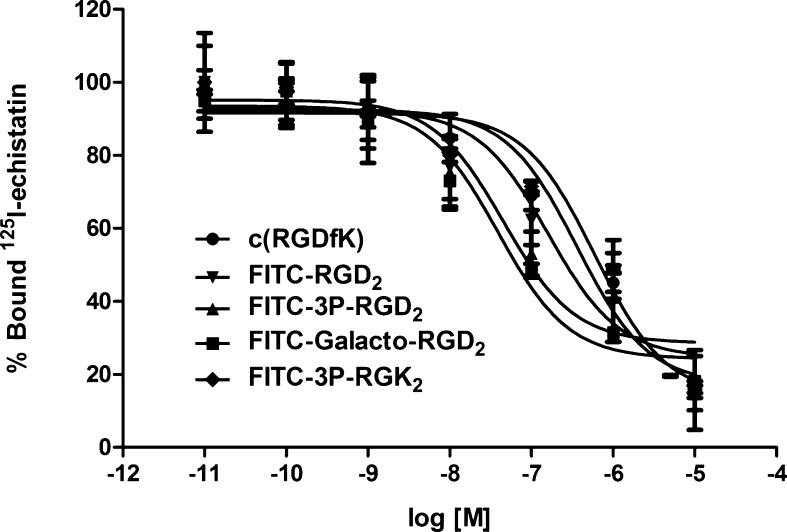

The whole-cell assay was used to determine integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding affinity of FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides. Figure 2 shows the displacement curves of 125I-echistatin bound to U87MG glioma cells in the presence of FITC-conjugated peptides. IC50 values were calculated to be 28 ± 8, 32 ± 7, 89 ± 17, and 589 ± 73 nM for FITC-Galacto-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, FITC-RGD2, and FITC-3P-RGK2, respectively. The IC50 value of c(RGDfK) (414 ± 36 nM) was close to that from our previous report.64−66 The integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding affinity followed a general trend: FITC-3P-RGD2 ∼ FITC-Galacto-RGD2 > FITC-RGD2 ≫ c(RGDfK) > FITC-3P-RGK2, which was consistent with the results for their DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetracetic acid) and HYNIC (6-(2-(2-sulfonatobenzaldehyde)hydrazono)nicotinyl) derivatives.44,60−71 The lower binding affinity of FITC-3P-RGK2 (IC50 = 589 ± 73 nM) than that of FITC-3P-RGD2 (IC50 = 32 ± 7 nM) clearly demonstrated the RGD-specificity of the FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides.

Figure 2.

Competitive displacement curves of 125I-echistatin bound to U87MG human glioma cells in the presence of FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides. Their IC50 values were obtained from curve fitting and were calculated to be 28 ± 8, 32 ± 7, 89 ± 17, 589 ± 73, and 414 ± 36 nM for FITC-Galacto-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGK2 and c(RGDfK), respectively. c(RGDfK) was used as a standard. 3P-RGK2 was the dimeric nonsense peptide to demonstrate the RGD-specificity of FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides.

Optimal Concentration for Tumor Tissue Staining

The concentration-dependence experiments were performed using the xenografted U87MG glioma and human carcinoma tissues. Figure 3 displays microscopic images of the xenografted U87MG glioma tissues stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 at 0.1, 1, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM, along with semiquantification of fluorescence intensity. The relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression in the U87MG glioma tumor was quantified as the percentage of green-colored (FITC-Galacto-RGD2) or red-colored (anti-integrin β3 antibody) area over the total area of each image. We found that all U87MG glioma tissues, which have high integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression on both tumor cells and neovasculature,22−33 were well stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 in the range of 10–100 μM. Very similar results were obtained with human carcinoma tissues (colon cancer, squamous cell lung cancer, and gastric cancer) stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (Supporting Information Figure SI1). The minimal concentration for positive staining of colon carcinoma was ∼5 μM. For squamous cell lung cancer tissues, a higher concentration (>25 μM) was needed in order to achieve adequate fluorescence staining. There was little staining in gastric carcinoma tissue, likely due to its low integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression. Since the higher concentrations were required for the tumor tissues with lower integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression, we used 100 μM of FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides for most of the staining studies in xenografted tumor tissues, and 50 μM of FITC-labeled cyclic RGD peptides for the staining of human carcinoma tissues.

Figure 3.

Microscopic images (Magnification: 200×) of the xenografted U87MG glioma tissues, and quantification of fluorescence intensity on tumor slice stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 at 0.1, 1, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM. Tumor tissues could be well-stained in the range of 10–100 μM.

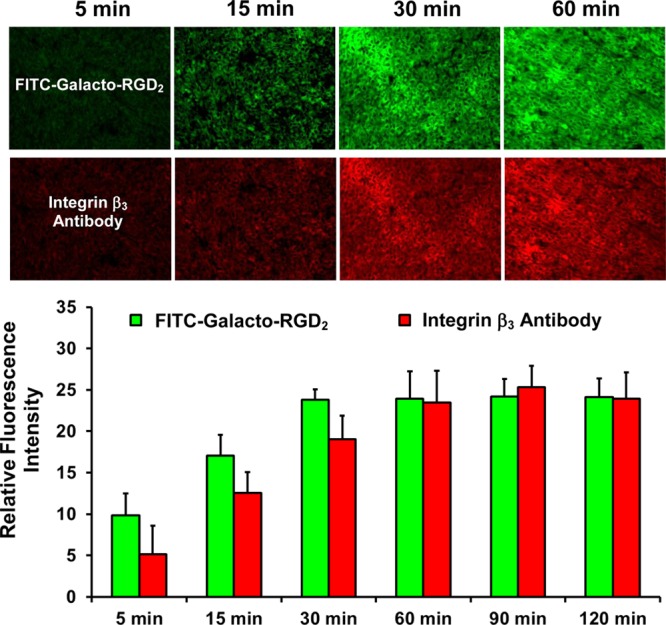

Tissue Staining Kinetics for Tumor Tissues

We explored the impact of incubation time on the fluorescent intensity of U87MG glioma and human carcinoma tissues stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (100 μM). We also performed IHC staining with anti-integrin β3 antibody using the same tumor slice in order to compare their staining kinetics (time-dependence) under identical experimental conditions. It was found that U87MG glioma tissues could achieve maximal fluorescent intensity with FITC-Galacto- RGD2 within 30 min while it took >60 min for the same tumor tissue using the anti-integrin β3 antibody (Figure 4). Similar results were obtained with human carcinoma tissues stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (Supporting Information Figure SI2). The colon cancer tissues were positively stained within 15 min of incubation. The faster staining kinetics of FITC-Galacto-RGD2 might explain the fact that the same tumor slice could be labeled with both FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and anti-integrin β3 monoclonal antibody. Considering the tumor tissues with lower integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression than that in U87MG glioma and colon cancer, the 60 min incubation time was used for most of the tumor tissue staining studies.

Figure 4.

Microscopic images (Magnification: 200×) of the xenografted U87MG glioma tissues stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green) and rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody (red), and tissue staining kinetics as indicated by fluorescence intensity at different incubation times (5–120 min).

Co-Localization of FITC-Conjugated Cyclic RGD Peptides with Integrin αvβ3 Antibody in Tumor Tissues

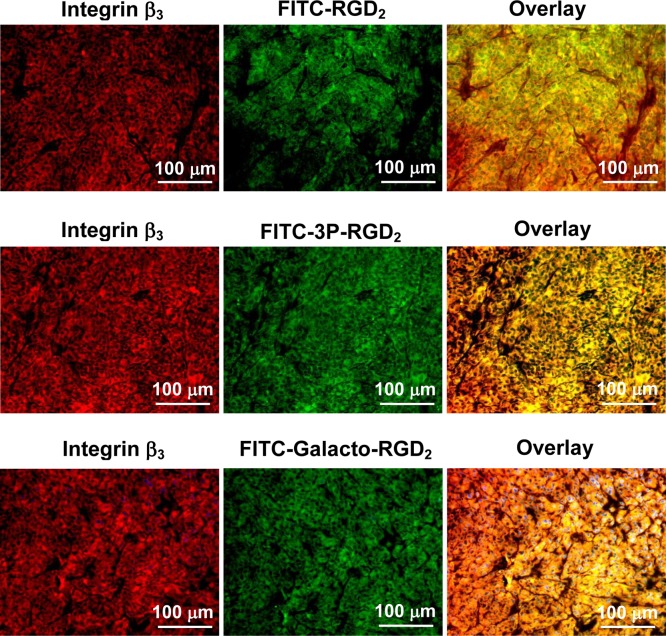

The overlay experiments were performed using the xenografted U87MG glioma (Figure 5) and human colon cancer (Figure 6) tissues to show the co-localization of FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides and rabbit anti-integrin β3 antibody. We found that the tumor tissues stained with FITC-3P-RGD2 or FITC-Galacto-RGD2 showed more fluorescence intensity than that with FITC-RGD2. In all cases, they were able to co-localize with anti-integrin β3 antibody, as evidenced by the orange and yellow colors (red integrin β3 antibody merged with green FITC-labeled cyclic RGD peptide) in overlay images. FITC-3P-RGD2 and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 were as effective for staining integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression as the anti-integrin β3 antibody for integrin αvβ3 in U87MG glioma and human carcinoma tissues. The same conclusion could be made for cellular staining integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 (Supporting Information Figures SI3–SI5).

Figure 5.

Microscopic images (200×) of the xenografted U87MG glioma tissues stained with FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptide (green) and rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody detected with Cy3 conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (red). Blue color indicates the presence of nuclei stained with DAPI. In overlay images, the orange and/or yellow color indicates co-localization of FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides (FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2) with rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody.

Figure 6.

Selected microscopic images (200× magnification) of colon carcinoma tissues stained with FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptide (green) and rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody detected with TR conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (red). Blue color indicates the presence of nuclei stained with DAPI. In overlay images, the orange and yellow colors (red integrin β3 merged with green cyclic RGD peptide) indicate co-localization of FITC-labeled cyclic RGD peptides (FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2) with anti-integrin β3 antibody.

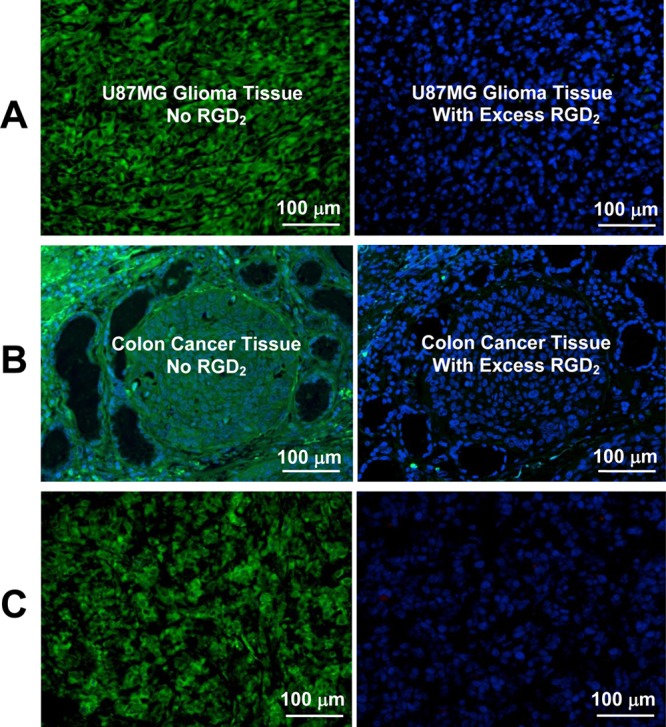

Integrin αvβ3/αvβ3 Specificity

Blocking experiments were performed using the xenografted U87MG glioma and human colon cancer to demonstrate the integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 specificity of the FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides. It was found that the xenografted U87MG glioma tissues were successfully stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2, but not in the presence of excess RGD2 (Figure 7A) due to blockage of integrin αvβ3/αvβ5. The same results were obtained with the human colon carcinoma tissues (Figure 7B). Figure 7C shows microscopic images of the tumor slice obtained from a U87MG-bearing mouse injected with ∼300 μg of FITC-Galacto-RGD2. The fluorescence intensity and distribution patterns in the xenografted U87MG glioma tissue (Figure 7C: left) were almost identical to those stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (Figure 7B: left). Further staining with the hamster anti-mouse integrin β3 antibody (Figure 7C: right) was not successful since all integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding sites on tumor tissues had already been occupied by FITC-Galacto-RGD2. The results from these blocking studies clearly showed that the tumor localization of FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 are integrin αvβ3/αvβ5-specific.

Figure 7.

(A) Selected microscopic images (Magnification: 400×) of living U87MG glioma cells stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 in the absence (left) and presence (right) of excess RGD2. (B) Microscopic images (Magnification: 200×) of a tumor slice stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 in the absence (left) and presence (right) of excess RGD2. (C) Microscopic images (Magnification: 200×) of the tumor slice (left), which was obtained from a tumor-bearing mouse administered with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 at a dose of 300 μg. Staining with hamster anti-mouse integrin β3 antibody (right) detected with Cy3 conjugated goat anti-hamster antibody (red) was not successful due to blockage of integrin αvβ3 by administration of excess FITC-Galacto-RGD2. (D) Microscopic images (Magnification: 200×) of human colon cancer slice stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 in the absence (left) and presence (right) of excess RGD2. Blue color indicates the nuclei stained with DAPI.

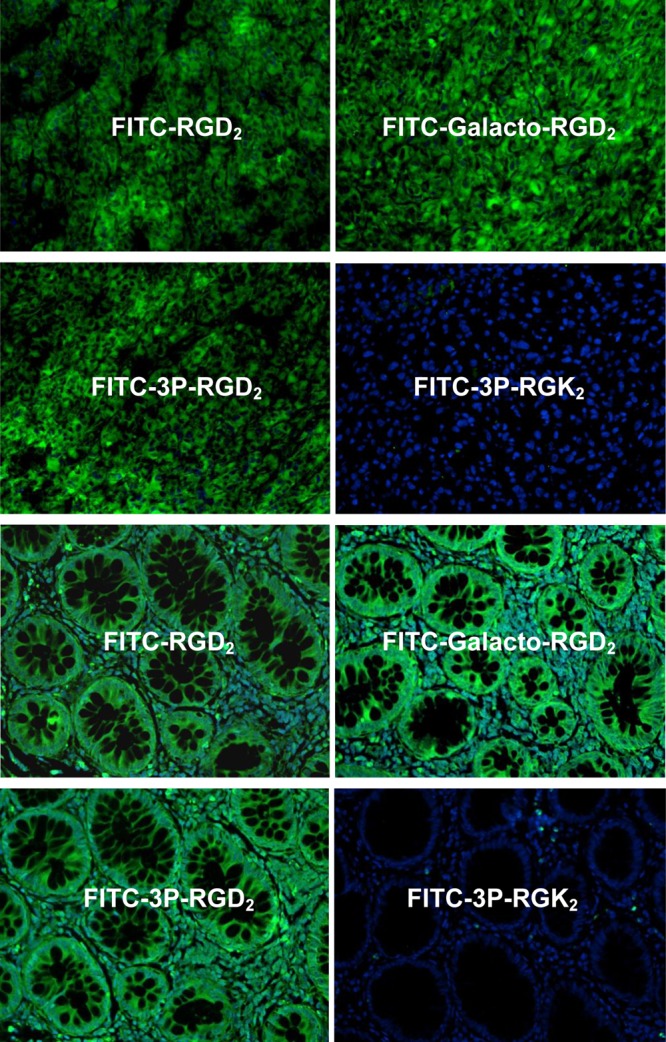

RGD Specificity

To demonstrate the RGD specificity of FITC-labeled cyclic RGD peptides, we used 3P-RGK2 as a “nonsense” peptide. Due to the RGK tripeptide sequence, FITC-3P-RGK2 had much lower integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding affinity than FITC-3P-RGD2 (Figure 2). Figure 8 shows microscopic images of the xenografted U87MG glioma tissues (top four panels) and the colon cancer tissues (bottom four panels) stained with FITC-RGD2, FITC-Galacto-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, or FITC-3P-RGK2. Apparently, the xenografted U87MG glioma and human colon cancer tissues were all positively stained with FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2, but not with FITC-3P-RGK2 under the same conditions. Thus, the tumor-binding of FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 is RGD-specific.

Figure 8.

(Top four images) Representative microscopic images of human colon cancer tissues (magnification: 200×) stained with FITC-RGD2, FITC-Galacto-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-3P-RGK2. (Bottom four images) Selected microscopic images of U87MG glioma tumor tissues (magnification: 200×) stained with FITC-RGD2, FITC-Galacto-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-3P-RGK2. Blue color indicates the presence of nuclei stained with DAPI.

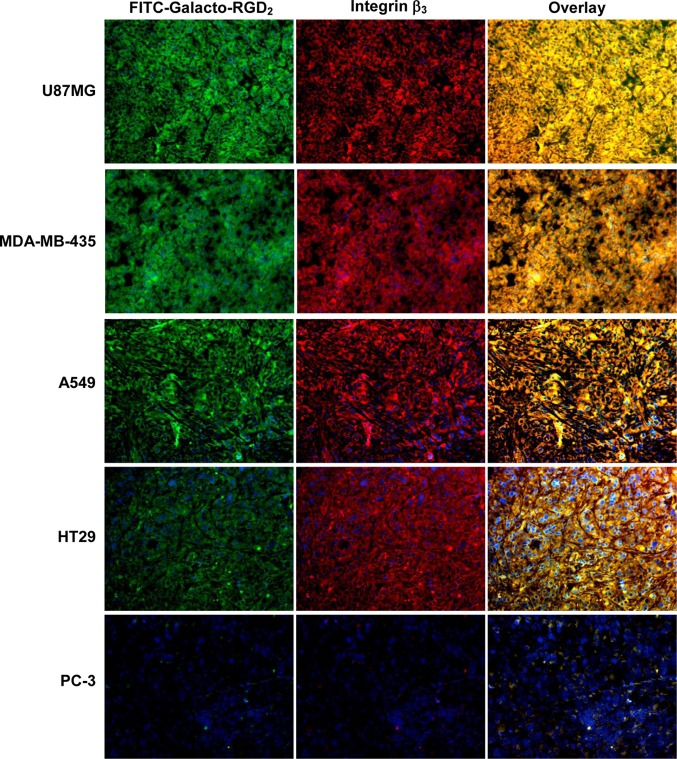

Quantification of Integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 Expression Xenografted Tumor Tissues

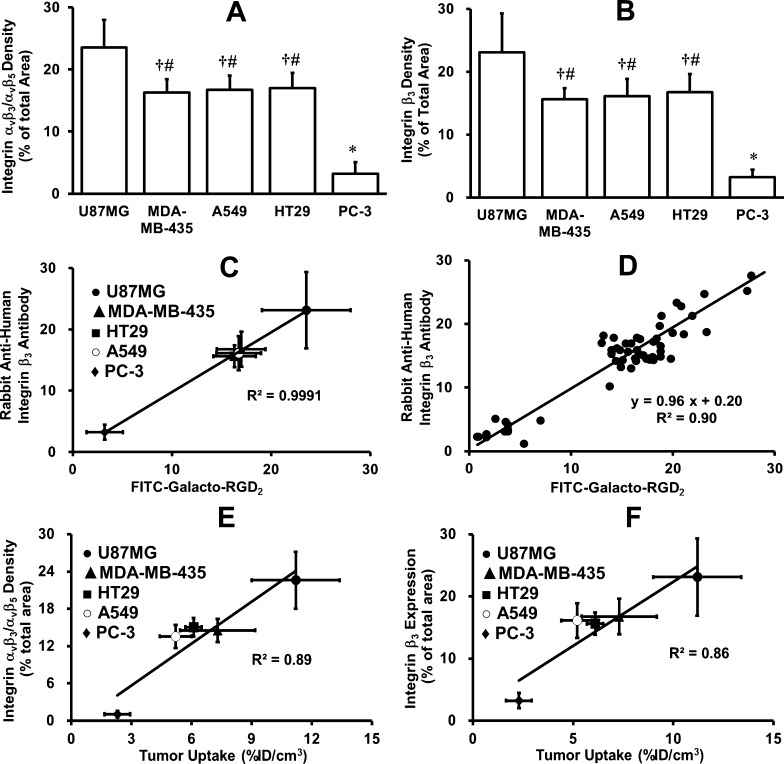

Quantification of the relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels was performed using five xenografted tumors (U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3). Figure 9 compares microscopic images of the xenografted tumors stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and anti-integrin β3 antibody. In overlay images, orange and yellow colors indicate co-localization of FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and anti-integrin β3 antibody. Figure 10 summarizes the quantification data of relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels in the xenografted U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3 tumor tissues. The fluorescent intensity (integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 density) on the tumor cells and tumor neovasculature was represented by the percentage of green (FITC-Galacto-RGD2) or red (anti-integrin β3 antibody) area over the total area in each image. We found that the integrin β3 (anti-integrin β3 antibody) and integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 (FITC-Galacto-RGD2) expression levels followed a general order of U87MG > HT29 ≈ MDA-MB-435 ≈ A549 ≫ PC-3 (Figure 10A,B). There was an excellent linear relationship (Figure 10C,D) between the relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels determined with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and the relative integrin αvβ3 expression levels obtained from the anti-integrin β3 antibody.

Figure 9.

Representative fluorescence microscopic images (Magnification: 200×) of selected tumor slices from five xenografted tumors stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green) and rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody detected with Cy3 conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (red). Orange or yellow in overlay image indicates co-localization of FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green) and integrin β3 antibody for tumor tissue staining of integrin avβ3.

Figure 10.

(A) Quantitative analysis of integrin αvβ3 density for five xenografted tumor tissues (U87MG, MDAMB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3) stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green). Integrin αvβ3 density on tumor cells and neovasculature is represented by the percentage of green area over the total area in each tumor slice. (B) Quantitative analysis of integrin β3 density for five different xenografted tumor tissues (U87MG, MDAMB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3) stained with rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody detected with the Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rat antibody (red). Integrin αvβ3 density on tumor cells and neovasculature is represented by the percentage of red area over the total area in each slice of tumor tissue. (C) (average data) and (D) (single data): Linear relationship between the relative integrin αvβ3 expression levels (fluorescence density) determined with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and those obtained with rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody in five xenografted tumors (U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3). Each data point was derived from 15 different areas of the same tumor slice. Experiments were repeated three times independently with very similar results. All experimental values are reported as the average plus/minus standard deviation. *: p < 0.01, significantly different from all other groups; †: p < 0.01, significantly different from the U87MG group; #: p < 0.01, significantly different from the PC-3 group. (E) (FITC-Galacto-RGD2) and (F) (rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody): Linear relationship between the relative integrin αvβ3 expression levels (fluorescence density) determined with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 or rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody and the tumor uptake values of 99mTc-3P-RGD2 in five xenografted tumors (U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3). The tumor uptake values of 99 mTc-3P-RGD2 were obtained from our previous studies.63

Linear Relationship between Tumor Uptake of 99mTc-3P-RGD2 and Relative Integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 Expression Level

99mTc-3P-RGD2 is an integrin αvβ3/αvβ5-targeted SPECT radiotracer under clinical evaluations for tumor imaging.72,73 Figure 10E,F shows the plots of its %ID/g tumor uptake (radioactivity density) and the relative integrin β3 expression levels (fluorescence density) determined with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 or the integrin β3 antibody in five different xenografted tumors (U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3). It was found that there was an excellent linear relationship between the %ID/g tumor uptake of 99mTc-3P-RGD2 and relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels with R2 being 0.89 for FITC-Galacto-RGD2, and the relative integrin αvβ3 expression levels with R2 being 0.86 for the anti-integrin β3 antibody. Therefore, the relative tumor integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels can be reflected by both %ID/g tumor uptake of 99mTc-3P-RGD2 and the fluorescence density determined by tissue staining with FITC-Galacto-RGD2.

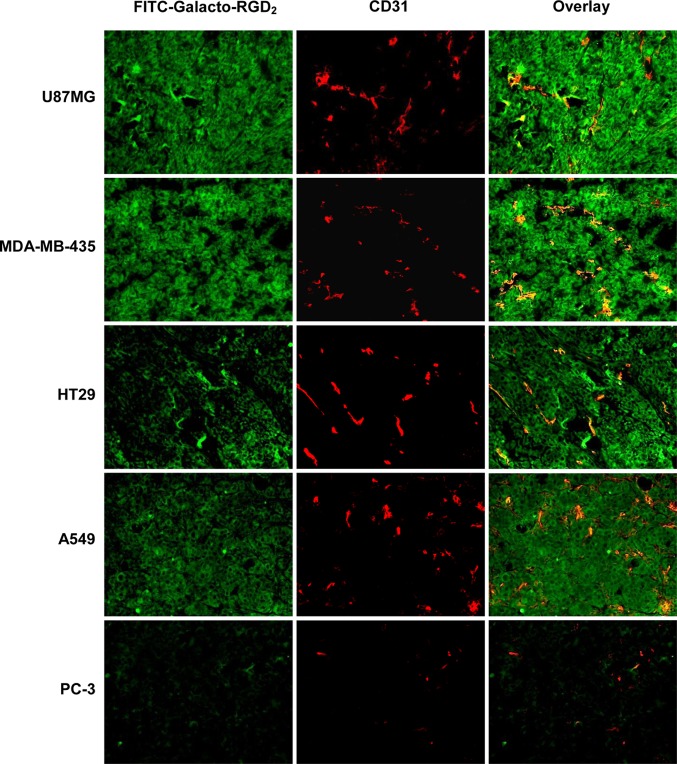

Integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 Expression on Tumor Neovasculature

It is well-established that the integrins αvβ3/αvβ5 are overexpressed on tumor cells and tumor neovasculature.36−39,60−62 The overlay experiments between FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green color) and CD31 antibody (red color) were performed using five different xenografted tumors (U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3). CD31 is a biomarker for endothelial cells on blood vessels. In the overlay images (Figure 11), orange and yellow colors indicated the presence of integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 on neovasculature. Even though it was difficult to quantify the relative tumor vasculature integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels, the results from the overlay images clearly showed that the FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides (e.g., FITC-Galacto-RGD2) were indeed able to bind to integrins αvβ3/αvβ5 on the tumor neovasculature. Similar results were reported in the overlay experiments using fluorescence-labeled integrin αvβ3 and CD31 antibodies.60,61 If there were no yellow or orange color (as in the case of the PC3 prostate model), there would be very little integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression on the tumor vasculature.

Figure 11.

Representative fluorescence microscopic images (Magnification: 200×) of selected tumor slices stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green) and rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody detected with Cy3 conjugated goat anti-rat antibody (red). Orange or yellow color in overlay images indicates co-localization of FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green) and CD31 antibody in tumor tissues.

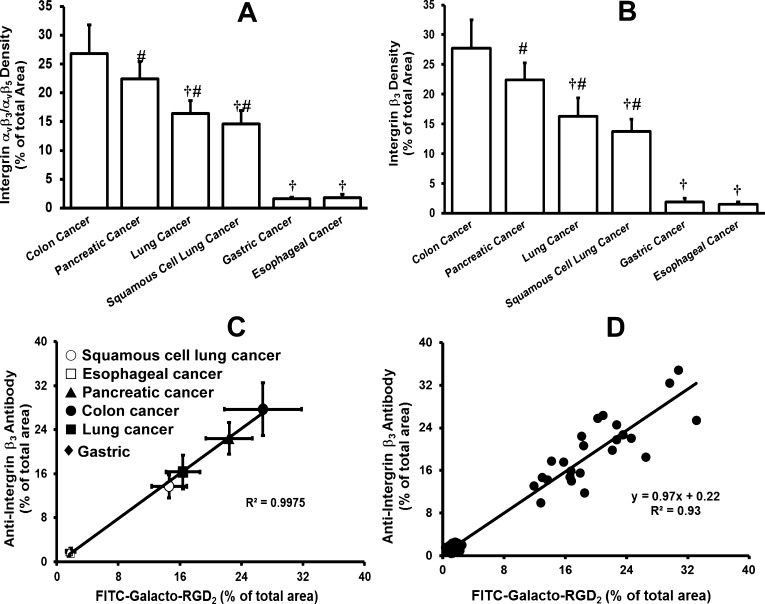

Quantification of Integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 Expression Levels in Human Carcinoma Tissues

Because of the vasculature difference between the xenografted tumors and human carcinoma tissues, we also evaluated FITC-Galacto-RGD2 for its utility as a fluorescent probe to quantify the relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels in human carcinoma tissues. Figure 12 compares macroscopic images of six human carcinoma tissues (colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, squamous cell lung cancer, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer) stained with both FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody. The quantitative analysis data were summarized in Figure 13 for human cancer tissues stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green for integrin αvβ3/αvβ5) and rabbit anti-integrin β3 antibody (red for integrin αvβ3). It was found that the integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels followed a general order: colon cancer > pancreatic cancer > lung adenocarcinoma ≈ squamous cell lung cancer ≫ gastric cancer ≈ esophageal cancer. There was an excellent linear relationship between the fluorescence density determined with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels) and that with anti-human integrin β3 antibody (integrin αvβ3 expression levels). The FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides (e.g., FITC-3P-RGD2 and FITC-Galacto-RGD2) are useful for semiquantification of relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels in human carcinoma tissues.

Figure 12.

Representative fluorescence microscopic images (Magnification: 200×) of selected tumor slices from six different human tumors (colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, squamous cell lung cancer, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer) stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green) and rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody detected with Cy3 conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (red). Orange or yellow in overlay image indicates co-localization of FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green) and integrin β3 antibody for tumor tissue staining of integrin avβ3. H&E staining data were used for pathological characterization of human carcinoma tissues.

Figure 13.

(A) Quantitative analysis of integrin αvβ3 density for six different human cancer tissues (colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, squamous cell lung cancer, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer) stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green). Integrin αvβ3 density on tumor cells and neovasculature is represented by the percentage of green area over the total area in each tumor slice. (B) Quantitative analysis of integrin β3 density for six human cancer tissues (colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, squamous cell lung cancer, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer) stained with rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody detected with the TR-conjugated goat anti-rat antibody (red). Integrin αvβ3 density on tumor cells and neovasculature is represented by the percentage of red area over the total area in each slice of tumor tissue. (C) (average data) and (D) (single data): Linear relationship between the relative integrin αvβ3 expression levels (fluorescence density) determined with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and those obtained with rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody in six human tumors (colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, squamous cell lung cancer, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer). Each data point was derived from 15 different areas of the same tumor slice. Experiments were repeated three times independently with very similar results. All values were reported as the average plus/minus standard deviation. †: p < 0.01, significantly different from the colon cancer group; #: p < 0.01, significantly different from the gastric cancer group.

Discussion

In this study, we found that FITC-3P-RGD2 and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 are excellent fluorescent probes for staining integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 in tumor tissues. The FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides are as effective as the fluorescence-labeled anti-integrin β3 antibody despite the fact that cyclic RGD peptides target both integrin αvβ3 and integrin αvβ5. The integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 specificity was demonstrated by the blocking experiments (Figure 7) and the RGD-specificity with the use of “nonsense” peptide conjugate FITC-3P-RGK2 (Figure 8). There is also an excellent linear relationship between the relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels determined with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and the relative integrin αvβ3 expression levels obtained with anti-integrin β3 antibody in the xenografted tumor tissues (U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3) (Figure 10C,D) and in the human carcinoma tissues (Figure 13C,D). There are three possible explanations for this linear relationship. First, the anti-human integrin β3 antibody can bind to both αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins. This explanation seems unlikely because the rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody (sc-14009) has been validated to be specific to integrin β3. The second possibility is that the integrin αvβ5 expression correlates linearly with the integrin αvβ3 expression levels. This explanation is problematic since integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5 are expressed at different levels on various tumor cells and tumor vasculature. Finally, the contribution from integrin αvβ5 is much smaller as compared to that of integrin αvβ3. This explanation is supported by careful examination of the slopes for the lines in Figure 10D (slope = 0.96 for five different xenografted tumor tissues) and Figure 13D (slope = 0.97 for six human carcinoma tissues). If both FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and the anti-human integrin β3 antibody (sc-14009) target only integrin αvβ3, the slope of these two lines is expected to be 1.0. Obviously, the binding of FITC-Galacto-RGD2 to integrin αvβ5 makes the slopes smaller than 1.0. The slight deviation suggests that only 3–4% of the fluorescent signals are from the integrin αvβ5. If the slope of these lines were to be 1.0, there would have been no contribution from integrin αvβ5 and other integrins. One might argue that integrin αvβ5 is highly expressed on HT29 cells,74 and U87MG human glioma cells have high expression of both integrin αvβ3 and integrin αvβ5.75−79 It is important to note that fluorescent intensity represents the total contribution from both tumor cells and neovasculature. It has been estimated that the % contribution from the tumor neovasculature to the total integrin αvβ3/avβ3 expression and tumor uptake of 99mTc-3P-RGD2 is ∼60% in the xenografted U87MG glioma model.80 In the case of xenografted HT29 tumors, the main contribution to the total fluorescent intensity or the tumor uptake of 99mTc-3P-RGD2 is actually from the integrin αvβ3 on new blood vessels.60,62

There is always a debate regarding whether one should separate αvβ3 from αvβ5. Integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5 both play a significant role in tumor angiogenesis,3,4,6−10 and often co-localize despite their different biological functions.16,30,39 Several integrin family members (including, but not limited to, αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, and α5β1) are receptors of the RGD-containing extracellular matrix proteins (e.g., vitronectin, fibronectin, fibrinogen, laminin, collagen, and osteoponin).1−12 As long as the biomolecule contains one or more RGD tripeptide sequences, it will target integrins αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, and α5β1 regardless of its multiplicity. From this point of view, there is no need to differentiate them for the development of radiotracers and fluorescent probes. This is the exact reason we use the whole-cell displacement assay with U87MG glioma cells (high expression of integrin αvβ3 and integrin αvβ5) as the host cells and 125I-echistatin, which is a 125I-labeled family member of disintegrins, as the radioligand in this study. Another important finding from this study is the linear relationship (Figure 10E,F) between the %ID/g tumor uptake of 99mTc-3P-RGD2 and the fluorescence density from the integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 staining with FITC-Galacto-RGD2. Visualization of integrins αvβ3/αvβ5 with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 makes it easier to correlate the in vitro tumor tissue staining data with the in vivo findings with the integrin αvβ3/αvβ5-targeted radiotracers, such as 99mTc-3P-RGD2 and [18F]Galacto-RGD (2-[18F]fluoropropanamide-c(RGDfK(SAA); SAA = 7-amino-l-glyero-l-galacto-2,6-anhydro-7-deoxyheptanamide).55−59 Such a combination of differently labeled analogs of the same cyclic peptide will improve the integration of both in vitro and in vivo diagnostics.

The tissue staining kinetics of the xenografted U87MG tumor and human colon cancer tissues with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (<30 min) is faster than that with anti-human integrin β3 antibody (>90 min required for blocking nonspecific binding, tissue staining, and attachment of secondary polyclonal antibody). This difference might be caused by the smaller size of FITC-Galacto-RGD2. Alternatively, this difference may also be caused by higher concentration of FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (>5 μM) than that of integrin β3 antibody (2.5 μg/mL or ∼12 nM), as illustrated by the concentration dependence of staining kinetics for human cancer tissues (Supporting Information Figure SI1). It is important to note that the staining kinetics of colon cancer tissue is faster than that of the xenografted U87MG tissues using the same fluorescent probe FITC-Galacto-RGD2 under similar conditions. We believe that this difference might be related to the total integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels because the tumor tissues with higher integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression tend to have a significantly faster tissue staining kinetics (Supporting Information Figure SI2) at a much lower concentration (Supporting Information Figure SI1).

There are several advantages in using FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides over the fluorescence-labeled integrin αvβ3 antibodies. The staining procedures with FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides are much simpler than those with fluorescence-labeled integrin αvβ3 antibodies since the latter involves the blocking of nonspecific binding and the use of secondary antibody. There is a significant variability in the performance of fluorescence-labeled integrin αvβ3 antibodies, depending on their origin (human, mouse, hamster, rabbit, or goat). In some cases, the results from tumor tissue staining may vary using different batches of antibodies from the same commercial source. In contrast, FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides have high solution stability, and can be stored for a long time. They are useful for the integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 staining in tumor tissues regardless of their origin (human vs murine). There is no need to block the nonspecific binding because they are integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 and RGD-specific. There is no need to use secondary antibody as fluorescence label because FITC can provide sufficient fluorescence signal to obtain excellent macroscopic images of integrin αvβ3/αvβ5-positive tumor tissues. There is also a significant disadvantage associated with FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides since they bind several integrin family members (αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, and α5β1). However, the tumor staining data with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 can be used to reflect the relative integrin αvβ3 expression levels because of the linear relationship between the fluorescent intensity with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and the integrin αvβ3 expression levels determined with anti-integrin β3 antibody in the xenografted tumor tissues (Figure 10C,D) and in the human carcinoma tissues (Figure 13C,D).

The heterogeneity in fluorescence distribution is characteristic of the xenografted tumors (U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, and HT29). In general, larger tumors (>0.5 g) tend to have more necrosis. In necrotic regions, there is little integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression, as indicted by lack of fluorescence in the area.60,61 It is not surprising that the human carcinoma tissues showed little integrin αvβ3 staining with the fluorescence-labeled integrin αvβ3 monoclonal antibodies even though the PET imaging data clearly showed high tumor uptake of [18F]Galacto-RGD in cancer patients.55−59 Thus, the selection of tumor biopsy samples becomes important for IHC staining of human carcinoma tissues with the FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides or fluorescence-labeled integrin αvβ3 antibodies. Since the human carcinoma tissues were only small parts of the whole tumor mass from cancer patients, caution must be taken when interpreting the quantification data in human carcinoma tissues stained with a FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptide or fluorescence-labeled integrin αvβ3 antibody. The integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels only represent the status of that specific tissue (not whole humor mass). In contrast, the integrin αvβ3/αvβ5-targeted PET and SPECT radiotracers (e.g., 99mTc-3P-RGD2 and [18F]Galacto-RGD) are better suited for determination and visualization of the tumor integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 heterogeneity due to the capability of PET and SPECT for in vivo imaging of entire tumor in cancer patients. Such a combination use of differently labeled (FITC vs 99mTc or 18F) derivatives of the same cyclic RGD peptide would improve the integration in assessment of integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels. This statement is completely consistent with the linear relationship (Figure 10E) between the %ID/g tumor uptake of 99mTc-3P-RGD2 in the xenografted tumors (U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3) and the fluorescent intensity obtained from semiquantification of the same five xenografted tumor tissues stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2. It must be noted that quantification of absolute fluorescence intensity is operator-dependent. The relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels only represent the status under specific experimental conditions (animal species and sexes, inoculation location, tumor cell types, tumor growth time, and tumor sizes).

Theoretically, FITC-Galacto-RGD2 would predominantly localize in the areas rich in blood vessels when it is injected intravenously. However, our results show that FITC-Galacto-RGD2 distributes in the whole tumor tissue in a relatively homogeneous fashion (Figure 7C). This might be caused by the leaky nature of microvessels and its long tumor retention time, during which FITC-Galacto-RGD2 could easily diffuse through the vessel walls and bind to all integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 sites in the whole tumor. This finding is important because it shows that FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides might be useful as fluorescent probes to correlate the in vitro findings with those in vivo data using the integrin αvβ3/αvβ5-targeted PET or SPECT radiotracers. This statement is supported by the linear relationship (Figure 10E) between the radioactivity density (%ID/g tumor uptake of 99mTc-3P-RGD2) and the integrin αvβ3 density obtained from fluorescent signal quantification of tumor tissues stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2.

The results from this study also show that FITC-Galacto-RGD2 is able to stain integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 on tumor neovasculature despite the difficulty for quantitative analysis. It is important to note that the quantification of fluorescent signals in each tumor slice reflects the total integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression on both tumor cells and neovasculature, and not all tumor blood vessels express integrin αvβ3/αvβ5. In fact, some tumor blood vessels have little integrin β3 expression in the xenografted U87MG glioma tissues as indicated by the red-color in the overlay images (Figure 11). Since the integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 is overexpressed only on tumor microvessels (not mature vessels), caution must be taken when correlating the radiotracer tumor uptake and blood vessel density (CD31 as a biomarker).

In this study, the FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides (e.g., FITC-Galacto-RGD2) are used only as examples to demonstrate proof-of-concept for the general approach to stain tumor tissues with small peptide-based fluorescent probes. Theoretically, this approach applies to any receptor-based fluorescent probe, as long as the targeting biomolecule has sufficient receptor binding affinity and specificity. Many radiolabeled peptides have been evaluated as target-specific radiotracers for molecular imaging of tumors by SPECT or PET.40−52 These peptides could be readily conjugated to a fluorescent label to produce the corresponding fluorescent probes. In addition, FITC could be easily replaced by other fluorescent dyes (such as red-colored cyanine derivatives) if needed.

Conclusion

The results from this study clearly illustrate the value of the FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides (particularly FITC-3P-RGD2 and FITC-Galacto-RGD2) for the in vitro assays of integrins αvβ3/αvβ5. They have very high solution stability and faster integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding kinetics. FITC-3P-RGD2 and FITC-Galacto-RGD2 are excellent fluorescent probes for assaying relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression levels in tumor tissues.

Experimental Section

Materials and Instruments

Common chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma/Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and were used without further purification. Fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer I (FITC) was purchased from AnaSpec, Inc. (Fremont, CA). Cyclic peptides E[c(RGDfK)]2 (RGD2), PEG4-E[PEG4-c(RGDfK)]2 (3P-RGD2), and PEG4-E[PEG4-c(RGKfD)]2 (3P-RGK2) were purchased from Peptides International, Inc. (Louisville, KY). Glu[cyclo[Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Phe-Lys(SAA-PEG2-(1,2,3-triazole)-1-yl-4-methylamide)]]2 (Galacto-RGD2) was prepared according to the procedures described in our previous report.64 The MALDI (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization) mass spectral data were collected on an Applied Biosystems Voyager DE PRO mass spectrometer (Framingham, MA), in the Department of Chemistry, Purdue University.

HPLC Methods

The HPLC method used a LabAlliance HPLC system (Scientific Systems, Inc., State College, PA) equipped with a UV/vis detector (λ = 220 nm) and Zorbax C18 column (9.4 mm × 250 mm, 100 Å pore size; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The flow rate was 2.5 mL/min with a mobile phase being 90% A (0.05% TFA in water) and 10% B (0.05% TFA in acetonitrile) at 0 min to 85% A and 15% B at 5 min, and to 75% A and 25% B at 20 min.

FITC-E[c(RGDfK)]2 (FITC-RGD2)

RGD2 (3.1 mg, 2.35 μmol) and FITC (1.2 mg, 3.08 μmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMF (1.5 mL). Upon addition of triethylamine (10 μL, 71 μmol), the reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h at room temperature. After completion of conjugation, 2 mL of water was added to the reaction mixture. The pH value was then adjusted to 3–4 using neat TFA. The resulting solution was subjected to HPLC purification. Fractions at 16 min were collected, combined, and lyophilized to yield FITC-RGD2 as a yellow powder (2.5 mg, ∼60%). MALDI-MS: m/z = 1707.4 for [M + H]+ (MW = 1706.69 calcd. for [C80H98N20O21S]).

FITC-PEG4-E[PEG4-c(RGDfK)]2 (FITC-3P-RGD2)

3P-RGD2 (4.15 mg, 2 μmol) and FITC (2.5 mg, 6.4 μmol) were dissolved in 2 mL of DMF. After addition of excess diisopropylethylamine (DIEA: 50 μmol), the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 days at room temperature. Upon completion of conjugation, 2 mL of water was added to the mixture above. The pH value was adjusted to 3–4 using neat TFA. The resulting solution was subjected to HPLC-purification. The fraction at ∼18 min was collected. Lyophilization of collected fractions afforded FITC-3P-RGD2 as a yellow powder (3.1 mg, ∼63%). MALDI-MS: m/z = 2450.55 for [M + H]+ (MW = 2449.68 calcd. for [C113H161N23O36S]).

PEG4-E[PEG4-c(RGKfD)]2 (FITC-3P-RGK2)

FITC-3P-RGK2 (4.15 mg, 2 μmol) was prepared and purified according to the same procedures for used for FITC-3P-RGD2. The fractions at ∼18 min were collected, combined, and lyophilized to afford FITC-3P-RGK2 as a yellow powder (2.3 mg, ∼47%). MALDI-MS: m/z = 2450.35 for [M + H]+ (MW = 2449.68 calcd. for [C113H161N23O36S]).

FITC-Glu[cyclo[Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Phe-Lys(SAA-PEG2-(1,2,3-triazole)-1-yl-4-methylamide)]]2 (FITC-Galacto-RGD2)

Galacto-RGD2 (6.5 mg, 3.02 μmol) and FITC (2.4 mg, 6.15 μmol) were dissolved in 2 mL of anhydrous DMF. After addition of excess DIEA (50 μmol), the reaction mixture was stirred for 5 days at room temperature. The reaction was terminated by adding 0.5 mL of 25 mM NH4OAC solution. The pH value was then adjusted to 3–4 using neat TFA. The resulting solution was subjected to HPLC-purification. The fraction at ∼16 min was collected. Lyophilization of the collected fractions afforded FITC-Galactor-RGD2 as a yellow powder (4.1 mg, ∼54%). MALDI-MS: m/z = 2538.85 for [M + H]+ (MW = 2538.62 calcd. for [C112H148N30O37S]).

Cellular Culture

All human tumor cell lines (U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). U87MG glioma cells were cultured in the Minimum Essential Medium, Eagle with Earle’s Balanced Salt Solution (nonessential amino acids sodium pyruvate, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PC-3 and A549 cells were cultured in the F-12 medium (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). MDA-MB-435 and HT29 cells were grown in the RPMI Medium 1640 with l-Glutamine (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). All human tumor cell lines were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS from Sigma/Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin solution (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), and grown at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. All tumor cells were grown as monolayers and were harvested or split when they reached 90% confluence to maintain exponential growth.

Whole-Cell Integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 Binding Assay

The integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 binding affinity was assessed via a cellular competitive displacement assay using 125I-echistatin (PerkinElmer, Branford, CT) as integrin-specific radioligand. Experiments were performed using the integrin αvβ3/αvβ3-positive U87MG glioma cells by slight modification of the literature method.64−75 Briefly, the filter multiscreen DV plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA) were seeded with 1 × 105 U87MG cells in the binding buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA); and pH 7.4) and were incubated with 125I-echistatin (0.75–1.0 kBq) for 2 h at room temperature in the presence of increasing concentrations of the FITC-conjugated peptides. After removing the unbound 125I-echistatin, the hydrophilic PVDF filters were washed three times with the binding buffer, and were then collected. Radioactivity was determined using a PerkinElmer Wizard −1480 γ-counter (Shelton, CT). All experiments were carried out at least twice with triplicate samples. IC50 values were calculated by fitting experimental data with nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prim 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA), and were reported as an average plus/minus standard deviation. Comparison between two FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides was made using the one-way ANOVA test (GraphPad Prim 5.0, San Diego, CA). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Animal Model

Animal studies were performed in compliance with the NIH animal experiment guidelines (Principles of Laboratory Animal Care, NIH Publication No. 86–23, revised 1985). The protocol for animal studies was approved by the Purdue University Animal Care and Use Committee (PACUC). Female athymic nu/nu mice (4–5 weeks) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN), and were implanted subcutaneously with 5 × 106 human tumor cells in 0.1 mL of saline into shoulder flanks (U87MG, A549, HT29, and PC-3) or mammary fat pads (MDA-MB-435). Four to six weeks after inoculation, the tumor size was 0.1–0.3 g. The tumors were then harvested for IHC and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

Human Carcinoma Tissues

Six human carcinoma tissues (colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, squamous cell lung cancer, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer) were obtained from the cancer patients with consent. Paraffin blocks of tumor tissues were obtained from the Department of Pathology, the China-Japan Friendship Hospital (Beijing, P. R. China). Original diagnoses were made between January 2011 and October 2012. All histological specimens were fixed for 12–24 h in neutrally buffered formaldehyde. The use of anonymous or coded leftover material for scientific purposes was part of the standard treatment contract with patients in the China-Japan Friendship Hospital (Beijing, P. R. China). For each case, hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stained slides of the paraffin blocks were reviewed by pathologists to confirm the malignancy in tumor tissues. Histological type was assessed according to the WHO classification of tumors. The protocol for use of human cancer tissues was approved by the Purdue University Animal Care and Use Committee (PACUC).

Tumor Tissue Staining

U87MG, MDA-MB-435, A549, HT29, and PC-3 tumors were harvested from the tumor-bearing mice, and were immediately snap-frozen in OCT (optical cutting temperature) solution, and then cut into slices (5 μm). After thorough drying at room temperature, slices were fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min, and dried in the air at the room temperature for 20 min. The tumor sections were incubated with 10% goat serum for 30 min at 37 °C to block nonspecific binding. In overlay experiments, the tumor sections were incubated with a FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptide (100 μM) and the rabbit antihuman β3 antibody (sc-14009, 2.5 μg/mL, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS buffer, the tumor slides were incubated for 1 h with the Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies (1:100, V/V Jackson Immuno-Research Inc., West Grove, PA). Negative controls were incubated only with secondary antibody. In blocking experiments, tumor slides were incubated with 10% goat serum, and then with 100 μM FITC-Galacto-RGD2 in the presence of 10 mM c(RGDfK)2 for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS three times, the tumor slides were mounted with Dapi Fluormount G and cover glass. To demonstrate the RGD specificity, FITC-3P-RGK2 (100 μM) was used as the nonsense peptide. For human carcinoma tissues (colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, squamous cell lung cancer, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer), the tumor slides were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated with alcohols, and then stained for integrin αvβ3 using the same procedure. All pictures were taken under 200× magnification with the same exposure time. Brightness and contrast adjustments were made equally to all images. The overlay images were obtained using Olympus MetaMorph software. Quantitative analysis of integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression was performed using ImageJ Software (the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The fluorescence intensity within images was quantified by assigning every pixel a gray scale intensity value, which ranged from 0 (black) to 255 (white). For quantification, the green (FITC-Galacto-RGD2) and red (rabbit anti-human integrin β3 antibody) channels in each image was exported into the software program. After calibrating optical density and adjusting threshold, the area of interest was measured as the percentage of total area. The area percentage of nucleus defined by DAPI staining was subtracted from the area percentage of cytoplasmic to compare the intensity of FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and anti-human integrin β3 antibody. At least 15 randomly selected fields of every section were used to assess relative fluorescent intensity. The fluorescence density was expressed as a percentage (%) of total area, and presented as an average plus/minus standard deviation.

Tumor Tissue Staining Kinetics: Concentration Dependence

U87MG tumor slices were fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min, and dried in the air for 20 min. The tumor sections were incubated for 1 h with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (0.1, 1.0, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM). After washing with PBS buffer three times, tumor slides were mounted with Dapi Fluormount G and cover glass. The same procedure was used for human carcinoma tissues (colon cancer with high integrin αvβ3 expression, squamous cell lung cancer with moderate integrin αvβ3 expression, and gastric cancer with low integrin αvβ3 expression) after being cut into slices (5 μm), deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated with degraded alcohols. Pictures were taken under 200× magnification with the same exposure time. Brightness and contrast adjustments were made equally to all images. The intensity was analyzed for the integrin αvβ3/αvβ5-positive staining areas as a percentage of the total area. The concentration-dependence histogram was generated by plotting fluorescent density against the concentration of FITC-Galacto-RGD2.

Tumor Tissue Staining Kinetics: Time Dependence

U87MG tumor slices (5 μm) were fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min, and dried in the air at room temperature. The tumor slices were then incubated with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (100 μM) at room temperature for different times (5, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min). After washing with PBS buffer three times, the tumor slices were mounted with Dapi Fluormount G and cover glass. For tissue staining with integrin β3 antibody, tumor slices were first incubated with 10% goat serum for 30 min at 37 °C to block the nonspecific binding, and then incubated with rabbit anti-integrin β3 antibody (sc-14009, 2.5 μg/mL) for different incubation times (5, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min). The slides were then incubated with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:100, V/V) for another 1 h before being mounted with Dapi Fluormount G and cover glass. Human carcinoma tissues (colon cancer, lung squamous cell cancer, and gastric cancer) were cut into slices (5 μm), deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated with degraded alcohols. The same procedure was performed for integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 staining. All pictures were taken under 200× magnification with the same exposure time. Brightness and contrast adjustments were made equally to all images. The fluorescent intensity was analyzed for the areas with integrin β3-positive staining after staining of tumor tissues according to the procedure above. The time-dependence histogram was generated by plotting fluorescent density against incubation time.

Blocking Experiment with Intravenous Injection of FITC-Galacto-RGD2

The athymic nude mice (n = 3) bearing U87MG glioma xenografts were intravenously injected with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (300 μg per animal). The animals were sacrificed at 24 h postinjection. Tumors were excised, immediately snap-frozen in the OCT solution, and cut into slices (5 μm). The tumor slices were dried at room temperature, fixed with ice-cold acetone for 15 min, and then dried in the air for 20 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS buffer three times, microscopic images were obtained using the same procedure above. For the overlay experiments, the tumor sections were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the hamster anti-mouse integrin β3 antibody (2.5 μg/mL, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). After washing with PBS three times, the tumor slides were incubated with the Cy3-conjugated goat anti-hamster secondary antibody (1:100, V/V, Jackson Immuno-Research Inc., West Grove, PA) for another 1 h at room temperature. Upon washing with PBS buffer, the tumor slides were then mounted with Dapi Fluormount G and cover glass.

Overlay Experiment with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and CD31 Monoclonal Antibody

The tumor slices (5 μm) were fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min, and dried in air for 20 min at room temperature. The tumor sections were blocked with 10% goat serum for 30 min, and then were incubated with 100 μM FITC-Galacto-RGD2 and the rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody (1:100, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 1 h at room temperature. After incubating with the Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rat secondary antibody (1:100, Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc., West Grove, PA) and washing with PBS buffer three times, the tumor slides were mounted with Dapi Fluormount G and cover glass. The fluorescence was visualized with an Olympic BX51 microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA).

Histopathological H&E Staining

Histological analysis of the tumor tissues was performed according to literature methods.64,65 All tumor tissues were fixed in 10% neutrally buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. The 4 μm sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated through degraded ethanol. Tumor sections were stained for H&E to evaluate the morphology. Aperio’s ImageScope Viewer (Vista, CA) was used to visualize the whole-slide digital scans and capture images.

Data and Statistical Analysis

The relative integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression level was derived from at least 15 different regions, and expressed as means plus/minus standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Newman-Keuls test for multiple comparisons. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by Purdue University, the Challenge Research Award from Purdue Cancer Center, the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute funded in part by grant Number TR000006 (Clinical and Translational Award) from the National Institutes of Health, the National Center for advancing Translational Science, R21 EB017237-01 (S.L.) from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), and grant number 81401446 from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Y.Z.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer I

- Galacto-RGD2

Glu[cyclo[Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Phe-Lys(SAA-PEG2-(1,2,3-triazole)-1-yl-4-methylamide)]]2 (SAA = 7-amino-l-glycero-l-galacto-2,6-anhydro-7-deoxyheptanamide, and PEG2 = 3,6-dioxaoctanoic acid)

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- MALDI

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization

- 3P-RGD2

PEG4-E[PEG4-c(RGKfD)]2 = PEG4-Glu[cyclo[Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Phe-Lys(PEG4)]]2 (PEG4 = 15-amino-4,7,10,13-tetraoxapentadecanoic acid)

- 3P-RGK2

PEG4-E[PEG4-c(RGKfD)]2 = PEG4-Glu[cyclo[Arg-Gly-Lys(PEG4)-d-Phe-Asp]]2)

- RGD2

E[c(RGDfK)]2 = Glu[cyclo(Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Phe-Lys)]2

- 99mTc-3P-RGD2

[99mTc(HYNIC-3P-RGD2)(tricine)(TPPTS)] (HYNIC = 6-hydrazinonicotinyl, and TPPTS = trisodium triphenylphosphine-3,3′,3″-trisulfonate)

- WHO

World Health Organization

Supporting Information Available

Detailed protocols for cellular staining of tumor cells, the concentration-dependence curve (Figure SI1), the incubation time-dependence curve (Figure SI2), microscopic images (Figure SI3) of U87MG human glioma cells stained with FITC-conjugated cyclic RGD peptides (Green) and mouse anti-human integrin αvβ3 antibody (sc-7312), microscopic images (Figure SI4) of acetone-fixed human cancer cells stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green) and mouse anti-human αvβ3 monoclonal antibody (sc-7312) detected with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (red), and microscopic images (Figure SI5) of living tumor cells stained with FITC-Galacto-RGD2 (green) and mouse anti-human αvβ3 monoclonal antibody (sc-7312) detected with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (red). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Andrzej Czerwinski, Francisco Valenzuela and Michael Pennington are from Peptides International, Inc. (Louisville, KY 40299), a commercial provider of biologically active peptides. There are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome. Yumin Zheng, Shundong Ji, and Shuang Liu declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Liu Z.; Wang F.; Chen X. (2008) Integrin αvβ3-targeted cancer therapy. Drug Dev. Res. 69, 329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhier F.; Le Breton A.; r at V. (2012) RGD-based strategies to target alpha(v) beta(3) integrin in cancer therapy and diagnosis. Mol. Pharmaceutics 9, 2961–2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. (1995) Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat. Med. 1, 27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrake H. M.; Patterson L. H. (2014) Strategies to inhibit tumor associated integrin receptors: rationale for dual and multi-antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 57, 6301–6315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. (2002) Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin. Oncol. 29, 15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang R.; Varner J. (2004) The role of integrins in tumor angiogenesis. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 18, 991–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergers G.; Benjamin L. E. (2003) Tumerogenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood J. D.; Cheresh D. A. (2002) Role of integrins in cell invasion and migration. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton M. A. (1997) The αvβ3 integrin “vitronectin receptor”. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 29, 721–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigelt B.; Peterse J. L.; van’t Veer L. J. (2005) Breast cancer metastasis: markers and models. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitzmann S.; Ehemann V.; Schwab M. (2002) Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD)-peptide binds to both tumor and tumor endothelial cells in vivo. Cancer Res. 62, 5139–5143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello L.; Francolini M.; Marthyn P.; Zhang J.; Carroll R. S.; Nikas D. C.; Strasser J. F.; Villani R.; Cheresh D. A.; Black P. M. (2001) αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin expression in glioma periphery. Neurosurgery 49, 380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögler O.; Mikkelsen T. (2003) Angiogenesis in glioma: molecular mechanisms and roadblocks to translation. Cancer J. 9, 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini G.; Brooks P. C.; Biganzoli E.; Vermeulen P. B.; Bonoldi E.; Dirix L. Y.; Ranieri G.; Miceli R.; Cheresh D. A. (1998) Vascular integrin αvβ3: a new prognostic indicator in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 4, 2625–2634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albelda S. M.; Mette S. A.; Elder D. E.; Stewart R.; Damjanovich L.; Herlyn M.; Buck C. A. (1990) Integrin distribution in malignant melanoma: association of the β3 subunit with tumor progression. Cancer Res. 50, 6757–6764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcioni R.; Cimino L.; Gentileschi M. P.; D’Agnano I.; Zupi G.; Kennel S. J.; Sacchi A. (1994) Expression of β1, β3, β4, and β5 integrins by human lung carcinoma cells of different histotypes. Exp. Cell Res. 210, 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S.; Chattopadhyay N.; Mitra A.; Ray S.; Dasgupta S.; Chatterjee A. (2001) Role of αvβ3 integrin receptors in breast tumor. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 585–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taherian A.; Li X.; Liu Y.; Haas T. A. (2011) Differences in integrin expression and signalling within human breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer 11, 293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A.; Cao W.; Chellaiah M. A. (2012) Integrin αvβ3 and CD44 pathways in metastatic prostate cancer cells support osteoclastogenesis via a Runx2/Smad 5/receptor activator of NF-κB ligand signaling axis. Mol. Cancer 11, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C. R.; Chay C. H.; Pienta K. J. (2002) The role of αvβ3 in prostate cancer progression. Neoplasia 4, 191–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreiras F.; Denoux Y.; Staedel C.; Lehmann M.; Sichel F.; Gauduchon P. (1996) Expression and localization of αv integrins and their ligand vitronectin in normal ovarian epithelium and in ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 62, 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felding-Habermann B.; Mueller B. M.; Romerdahl C. A.; Cheresh D. A. (1992) Involvement of integrin αv gene expression in human melanoma tumorigenicity. J. Clin. Invest. 89, 2018–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felding-Habermann B.; O’Toole T. E.; Smith J. W.; Fransvea E.; Ruggeri Z. M.; Ginsberg M. H.; Hughes P. E.; Pampori N.; Shattil S. J.; Saven A.; Mueller B. M. (2001) Integrin activation controls metastasis in human breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 1853–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolli M.; Fransvea E.; Pilch J.; Saven A.; Felding-Habermann B. (2003) Activated integrin αvβ3 cooperates with metalloproteinase MMP-9 in regulating migration of metastatic breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 9482–9487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felding-Habermann B. (2003) Integrin adhesion receptors in tumor metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 20, 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattil S. J. (1999) Signaling through platelet integrin αIIbβ3: inside-out, outside-in, and sideways. Thromb. Haemost. 82, 318–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pécheur I.; Peyruchaud O.; Serre C. M.; Guglielmi J.; Voland C.; Bourre F.; Margue C.; Cohen-Solal M.; Buffet A.; Kieffer N.; Clézardin P. (2002) Integrin αvβ3 expression confers on tumor cells a greater propensity to metastasize to bone. FASEB J. 16, 1266–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felding-Habermann B.; Fransvea E.; O’Toole T. E.; Manzuk L.; Faha B.; Hensler M. (2002) Involvement of tumor cell integrin αvβ3 in hematogenous metastasis of human melanoma cells. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 19, 427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilch J.; Habermann R.; Felding-Habermann B. (2002) Unique ability of integrin αvβ3 to support tumor cell arrest under dynamic flow conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 21930–21938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar T.; Heyder C.; Gloria-Maercker E.; Hatzmann W.; Zänker K. S. (2008) Adhesion molecules and chemokines: the navigation system for circulating tumor (stem) cells to metastasize in an organ-specific manner. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 25, 11–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omar O.; Lennerås M.; Svensson S.; Suska F.; Emanuelsson L.; Hall J.; Nannmark U.; Thomsen P. (2010) Integrin and chemokine receptor gene expression in implant-adherent cells during early osseointegration. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 21, 969–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minn A. J.; Kang Y.; Serganova I.; Gupta G. P.; Giri D. D.; Doubrovin M.; Ponomarev V.; Gerald W. L.; Blasberg R.; Massagué J. (2005) Distinct organ-specific metastatic potential of individual breast cancer cells and primary tumors. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorger M.; Krueger J. S.; O’Neal M.; Staflin K.; Felding-Habermann B. (2009) Activation of tumor cell integrin αvβ3 controls angiogenesis and metastatic growth in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 10666–10671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan E. K.; Pouliot N.; Stanley K. L.; Chia J.; Moseley J. M.; Hards D. K.; Anderson R. L. (2006) Tumor-specific expression of αvβ3 integrin promotes spontaneous metastasis of breast cancer to bone. Breast Cancer Res. 8, R20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X.; Jia S. F.; Zhou Z.; Langley R. R.; Bolontrade M. F.; Kleinerman E. S. (2004) Association of αvβ3 integrin expression with the metastatic potential and migratory and chemotactic ability of human osteosarcoma cells. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 21, 747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousa S. A. (1998) Mechanisms of angiogenesis in vascular disorders: potential therapeutic targets. Drugs Future 23, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Burke P. A.; DeNardo S. J. (2001) Antiangiogenic agents and their promising potential in combined therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 39, 155–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar C. C. (2003) Integrin αvβ3 as a therapeutic target for blocking tumor-induced angiogenesis. Curr. Drug Targets 4, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H.; Varner J. (2004) Integrins: roles in cancer development and as treatment targets. Br. J. Cancer 90, 561–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea L. D.; Del Gatto A.; Pedone C.; Benedetti E. (2006) Peptide-based molecules in angiogenesis. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 67, 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W.; Niu G.; Chen X. (2008) Imaging of integrins as biomarkers for tumor angiogenesis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14, 2943–2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer A. J.; Schwaiger M. (2008) Imaging of integrin αvβ3 expression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 27, 631–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A.; Auermheimer J.; Modlinger A.; Kessler H. (2006) Targeting RGD recognizing integrins: drug development, biomaterial research, tumor imaging and targeting. Curr. Pharm. Des 12, 2723–2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. (2009) Radiolabeled cyclic RGD peptides as integrin αvβ3-targeted radiotracers: maximizing binding affinity via bivalency. Bioconjugate Chem. 20, 2199–2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkgraaf I.; Boerman O. C. (2010) Molecular imaging of angiogenesis with SPECT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 37(Suppl 1), S104–S113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Chakraborty S.; Liu S. (2011) Radiolabeled cyclic RGD peptides as radiotracers for imaging tumors and thrombosis by SPECT. Theranostics 1, 58–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalski M. H.; Chen X. (2011) Molecular imaging in cancer treatment. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 38, 358–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateishi U.; Oka T.; Inoue T. (2012) Radiolabeled RGD Peptides as integrin αvβ3–targeted PET tracers. Curr. Med. Chem. 19, 3301–3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fani M.; Maecke H. R. (2012) Radiopharmaceutical development of radiolabelled peptides. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 39(Suppl 1), S11–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner F. C.; Kessler H.; Wester H. J.; Schwaiger M.; Beer A. J. (2012) Radiolabelled RGD peptides for imaging and therapy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 39(Suppl 1), S126–S138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverman P.; Sosabowski J. K.; Boerman O. C.; Oyen W. J. G. (2012) Radiolabelled peptides for oncological diagnosis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 39(Suppl 1), S78–S92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamous M.; Haberkorn U.; Mier W. (2013) Synthesis of peptide radiopharmaceuticals for the therapy and diagnosis of tumor diseases. Molecules 18, 3379–3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.; Li Z. B.; Chen K.; Cai W.; He L.; Chin F. T.; Li F.; Chen X. (2007) MicroPET of tumor integrin αvβ3 expression using 18F-labeled PEGylated tetrameric RGD peptide (18F-FPRGD4). J. Nucl. Med. 48, 1536–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Xiong Z.; Wu Y.; Cai W.; Tseng J. R.; Gambhir S. S.; Chen X. (2006) Quantitative PET imaging of tumor integrin αvβ3 expression with 18F-FRGD2. J. Nucl. Med. 47, 113–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubner R.; Weber W. A.; Beer A. J.; Vabuliene E.; Reim D.; Sarbia M.; Becker K. F.; Goebel M.; Hein R.; Wester H. J.; Kessler H.; Schwaiger M. (2005) Noninvasive visualization of the activated αvβ3 integrin in cancer patients by positron emission tomography and [18F]Galacto-RGD. PLoS Med. 2, 244–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer A. J.; Haubner R.; Sarbia M.; Goebel M.; Luderschmidt S.; Grosu A. L.; Schnell O.; Niemeyer M.; Kessler H.; Wester H. J.; Weber W. A.; Schwaiger M. (2006) Positron emission tomography using [18F]Galacto-RGD identifies the level of integrin αvβ3 expression in man. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 3942–3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer A. J.; Grosu A. L.; Carlsen J.; Kolk A.; Sarbia M.; Stangier I.; Watzlowik P.; Wester H. J.; Haubner R.; Schwaiger M. (2007) [18F]Galacto-RGD positron emission tomography for imaging of αvβ3 expression on the neovasculature in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 6610–6616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer A. J.; Lorenzen S.; Metz S.; Herrmann K.; Watzlowik P.; Wester H. J.; Peschel C.; Lordick F.; Schwaiger M. (2008) Comparison of integrin αvβ3 expression and glucose metabolism in primary and metastatic lesions in cancer patients: a PET study using 18F-Galacto- RGD and 18F-FDG. J. Nucl. Med. 49, 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell O.; Krebs B.; Carlsen J.; Miederer I.; Goetz C.; Goldbrunner R. H.; Wester H. J.; Haubner R.; Pöpperl G.; Holtmannspötter M.; Kretzschmar H. A.; Kessler H.; Tonn J. C.; Schwaiger M.; Beer A. J. (2009) Imaging of integrin αvβ3 expression in patients with malignant glioma [18F]Galacto-RGD positron emission tomography. Neuro. Oncol. 11, 861–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Kim Y. S.; Chakraborty S.; Shi J.; Gao H.; Liu S. (2011) 99mTc-labeled cyclic RGD peptides for noninvasive monitoring of tumor integrin αvβ3 expression. Mol. Imaging 10, 386–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Kim Y. S.; Lu X.; Liu S. (2012) Evaluation of 99mTc-labeled cyclic RGD dimers: impact of cyclic RGD peptides and 99mTc chelates on biological properties. Bioconjugate Chem. 23, 586–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschauer S.; Haubner R.; Kuwert T.; Prante O. (2014) 18F-Glyco-RGD peptides for PET imaging of integrin expression: efficient radiosynthesis by click chemistry and modulation of biodistribution by glycosylation. Mol. Pharmaceutics 11, 505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Liu S.; Niu G.; Wang F.; Liu S.; Chen X. (2010) Optical imaging of integrin αvβ3 expression with near-infrared fluorescent RGD dimer with tetra(ethylene glycol) linkers. Mol. Imaging 9, 21–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji S.; Czerwinski A.; Zhou Y.; Shao G.; Valenzuela F.; Sowiński; Chauhan S.; Pennington M.; Liu S. (2013) 99mTc-Galacto-RGD2: a novel 99mTc-labeled cyclic RGD peptide dimer useful for tumor imaging. Mol. Pharmaceutics 10, 3304–3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Shi J.; Kim Y. S.; Zhai S.; Jia B.; Zhao H.; Liu Z.; Wang F.; Chen X.; Liu S. (2009) Improving tumor targeting capability and pharmacokinetics of 99mTc-labeled cyclic RGD dimers with PEG4 linkers. Mol. Pharmaceutics 6, 231–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Wang L.; Kim Y. S.; Zhai S.; Liu Z.; Chen X.; Liu S. (2008) Improving tumor uptake and excretion kinetics of 99mTc-labeled cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartic (RGD) dimers with triglycine linkers. J. Med. Chem. 51, 7980–7990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Wang L.; Kim Y. S.; Zhai S.; Jia B.; Wang F.; Liu S. (2009) 99mTcO(MAG2-3G3-dimer): a new integrin αvβ3-targeted SPECT radiotracer with high tumor uptake and favorable pharmacokinetics. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 36, 1874–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Kim Y. S.; Zhai S.; Liu Z.; Chen X.; Liu S. (2009) Improving tumor uptake and pharmacokinetics of 64Cu-labeled cyclic RGD peptide dimers with triglycine and PEG4 linkers. Bioconjugate Chem. 20, 750–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Kim Y. S.; Chakraborty S.; Jia B.; Wang F.; Liu S. (2009) 2-Mercaptoacetylglycylglycyl (MAG2) as a bifunctional chelator for 99mTc-labeling of cyclic RGD dimers: effects of technetium chelate on tumor uptake and pharmacokinetics. Bioconjugate Chem. 20, 1559–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S.; Shi J.; Kim Y. S.; Zhou Y.; Jia B.; Wang F.; Liu S. (2010) Evaluation of 111In-labeled cyclic RGD peptides: tetrameric not tetravalent. Bioconjugate Chem. 19, 969–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Zhou Y.; Chakraborty S.; Kim Y. S.; Jia B.; Wang F.; Liu S. (2011) Evaluation of 111In-labeled cyclic RGD peptides: effects of peptide and linker multiplicity on their tumor uptake, excretion kinetics and metabolic stability. Theranostics 1, 322–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q.; Ji B.; Jia B.; Gao S.; Ji T.; Wang X.; Han Z.; Zhao G. (2011) Differential diagnosis of solitary pulmonary nodules using 99mTc-3P4-RGD2 scintigraphy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 38, 2145–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z.; Miao W.; Li Q.; Dai H.; Ma Q.; Wang F.; Yang A.; Jia B.; Jing X.; Liu S.; Shi J.; Liu Z.; Zhao Z.; Li F. (2012) 99mTc-3PRGD2 for integrin receptor imaging of lung cancer: a multicenter study. J. Nucl. Med. 53, 716–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemperman H.; Wijnands Y. M.; Roos E. (1997) αv Integrins on HT-29 colon carcinoma cells: adhesion to fibronectin is mediated solely by small amounts of αVβ6, and αVβ5 is codistributed with actin fibers. Exp. Cell Res. 234, 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth P.; Silginer M.; Goodman S. L.; Hasenbach K.; Thies S.; Maurer G.; Schraml P.; Tabatabai G.; Moch H.; Tritschler I.; Weller M. (2013) Integrin control of the transforming growth factor-β pathway in glioblastoma. Brain 136, 564–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]