Abstract

Potentilla matsumurae has a wide distribution from wind‐blown fellfields to snowbeds in alpine regions of Japan. The environmental factors influencing seedling establishment differ between the fellfield and snowbed habitats; plants growing in each habitat may therefore have different germination strategies. Using a reciprocal sowing experiment, patterns of seedling emergence and survivorship were examined in both habitat types in the Taisetsu Mountains, Japan. Seeds derived from a fellfield population germinated earlier than did those derived from a snowbed population at both habitats, and the germination of fellfield seeds continued throughout the growing season. The timing of seedling emergence greatly affected subsequent survival at the fellfield. Seedlings that emerged in the first half of the growing season had low survivorship during the first year because of frost and drought damage, but the remaining seedlings had high survivorship during the winter; seedlings that emerged in the latter half of the growing season showed the opposite trend. At the snowbed, seedling survival was high throughout the growing season. Germination experiments in the laboratory highlighted a difference in the sensitivity of seeds from the fellfield and snowbed populations to fluctuating temperatures. These results indicate that intraspecific variation in emergence and survivorship may occur over a small scale in an alpine environment.

Key words: Potentilla matsumurae Th. Wolf, fellfield, snowbed, germination pattern, seedling survivorship, temperature fluctuation, intraspecific variation

INTRODUCTION

In most plants the seedling stage of the life cycle is the stage of development that is most sensitive to environmental variation. Hence, the timing of seed germination is of critical importance to subsequent survival of seedlings under environmental conditions subject to seasonal fluctuations (Maruta, 1976; Baskin and Baskin, 1979; Kachi and Hirose, 1990). Many studies have reported habitat‐specific variations in germination patterns among species (Meyer et al., 1995; Nishitani and Masuzawa, 1996; Vera, 1997) and between populations of a single species (McWilliams et al., 1968; Groves et al., 1982; Meyer and Monsen, 1991; Mariko et al., 1993; Beckstead et al., 1996; Meyer et al., 1997). If environmental factors affect seedling survival differently among populations then variations in the timing of seed germination among populations can be considered to be a life‐history strategy.

Alpine environments are useful for studying small‐scale population differentiation because environmental conditions change rapidly within a local area due to variations in the timing of snow melt which reflect micro‐topographic differences (Billings and Bliss, 1959; Miller, 1982; Onipchenko et al., 1998; Körner, 1999). Little snow accumulates at wind‐blown fellfields, resulting in frozen soil in winter, frost damage in spring and drought stress during the summer. On the other hand, snow patches remain at snowbeds until summer; these protect plants from freezing and frost damage, and provide water during the summer (Körner, 1999). Nutrient availability and plant cover are generally higher, and biomass and moisture conditions more favourable in snowbed compared with fellfield habitats, but the growing season is much shorter in the former (Miller, 1982). Thus, factors affecting seedling establishment should differ between fellfield and snowbed habitats.

Soil drought and needle ice activity are common environmental stresses that affect the establishment of seedlings of alpine plants (Billings and Mooney, 1968). At fellfields, the diurnal soil surface temperature may be above 30 °C on sunny days, even in early spring, but frost often occurs irregularly in this season. Thus, simultaneous germination in the early part of the growing season may result in complete failure of seedling establishment due to spring‐frost or snow. Furthermore, soil containing less organic matter, and topographically windy locations, may limit seedling establishment at fellfields due to repeated drought stress during the summer. As a result, seeds of fellfield plants may germinate intermittently throughout the growing season. The growing season in snowbed habitats is shorter than that at fellfields. Hence, seedlings must attain a critical size by the end of the first growing season to increase their chances of survival over winter (Maruta, 1983, 1994). One possible strategy for maximizing the period of plant growth in snowbed habitats would be for seedlings to germinate as early as possible after snowmelt. Such variations in the timing of germination are expected to occur not only between fellfield‐ and snowbed‐specific species, but also within species whose distribution includes both fellfields and snowbeds.

Fresh seeds of many arctic and alpine plant species germinate readily without any cold stratification treatment (Sayers and Ward, 1966; Bell and Bliss, 1980). Therefore, most overwintered seeds will germinate readily whenever a combination of temperature and moisture conditions suitable for germination is attained. However, the extent of intraspecific variation in germination traits and relationships between variation in the timing of germination and subsequent survival have rarely been studied in alpine plants.

In this study, habitat‐specific variations in germination traits were examined in fellfield and snowbed populations of Potentilla matsumurae Th. Wolf by means of a reciprocal sowing experiment between the two habitat types in the Taisetsu Mountains in northern Japan. In addition, germination experiments were conducted in the laboratory to determine whether environmental factors such as temperature and water availability are associated with the pattern of germination. Germination was observed under five temperature regimes to detect differences in temperature‐dependent germination patterns between the fellfield and snowbed populations. Sensitivity to temperature fluctuation and water availability was then assessed for the populations by exposing seeds to three different water potentials under two temperature conditions that simulated diurnal temperatures in the field in June and July.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites

This study was conducted at fellfields and snowbeds situated at elevations of 1700–1900 m in the central part of the Taisetsu Mountains (43°13′–45′N, 142°32′–143°19′E), Hokkaido, northern Japan. Snowfall begins in late September and continues until early June. Two 20 m × 20 m plots (F1 and F2) were chosen at the fellfield, and three 20 m × 20 m plots (S1, S2 and S3) at the snowbed. Plots were located 100–1900 m apart.

The F1 plot was located on a terrace at 1700 m a.s.l., and the F2 plot was located on a ridge at 1900 m a.s.l. Both plots have little snow accumulation during the winter due to strong seasonal winds, and the ground temperature can reach –15 °C. The dominant species in both plots were the dwarf shrubs Empetrum nigrum L. var. japonicum K. Koch, Diapensia lapponica L. ssp. obovata (F. Schm.) Hultén, Loiseleuria procumbens (L.) Desv. and Bryanthus gmelinii D. Don, and lichens (mainly Cladonia and Cetraria species).

The three snowbed plots were located on a south‐east‐facing slope at 1790–1880 m a.s.l. Owing to the thick snow cover, the soil surface temperature remains constant at 0 °C during the winter. Snow disappeared from the S1 to S3 plots every year. At the S1 plot, snow usually disappeared around mid‐ to late June. The dominant species in this plot were the dwarf shrubs Phyllodoce caerulea (L.) Bab. and Sieversia pentapetala (L.) Greene, and the herbs Anemone narcissiflora L. var. sachalinensis Miyabe et Miyake and Arnica unalaschcensis Less. var. unalaschcensis. Snow usually disappeared in July at the S2 plot, and between late July and early August at the S3 plot. The dominant species in these two plots were the dwarf shrubs Phyllodoce aleutica (Spreng.) A. Heller, P. caerulea and S. pentapetala, and the herbs Primula cuneifolia Ledeb., Peucedanum multivittatum Cufod. and Veronica stelleri Pall. ex Link var. longistyla Kitag.

The timing of snow disappearance was recorded in 1997, 1998 and 1999 at each snowbed plot, and the soil surface temperature was recorded hourly (Optic StowAway; Onset Co., USA) from May 1997 to late‐September 1999 at the F1 and S2 plots. From June to September during 1997–1999, precipitation and global radiation were measured at a meteorological station established at the F1 plot.

Plant material

Potentilla matsumurae Th. Wolf is a common perennial herb that occurs in several types of habitat in the mountains of Japan. Individual plants typically produce one to seven hermaphrodite flowers per inflorescence. Flowers are visited mainly by dipteran insects. Because the flowering season varies from early June to early August, according to the time of snow disappearance, temporal isolation of anthesis occurs amongst adjacent populations experiencing different snowmelt schedules. The seeds are mature approx. 1 month after flowering, so seed maturation is possible even in late snowmelt habitats (Kudo, 1991). Plants from the snowbed populations tended to produce lighter seeds (mean 0·31–0·43 mg) than did those from the fellfield populations (mean 0·38–0·50 mg). Seeds are dispersed passively around the parent plants.

Reciprocal sowing experiment in the field

The F1 and S2 plots were selected as representative of the fellfield and snowbed habitats, respectively, and were used in a reciprocal sowing experiment. Bulk seed was harvested on 19 Jul. 1997 at the F1 plot and on 15 Aug. 1997 at the S2 plot from more than 20 individuals chosen at random. One hundred seeds were sown in a plastic pot (10 cm diameter, 10 cm deep) filled with soil from bare land at the local plot, and thinly covered (approx. 1 mm) with vermiculite. Seeds from each plot were sown in ten pots. Seed from bare land at the F1 plot was sown at both the F1 and S2 plots (five pots per site) on 26 Jul. 1997, whereas seed from the S2 plot was sown at both the S2 and F1 plots (five pots per site) on 27 Aug. 1997. Pots were buried such that the rim was level with the surface of the soil. Pots were covered with fine mesh to minimize seed predation on the soil surface and to prevent further seed inputs via wind or animal dispersal. Seedling emergence and survival were recorded at 10‐d intervals for 2 years during the growing season.

Leaf length and width (mm) of each seedling were measured on 6 Sep. 1998 to estimate the size of seedlings at the end of the first year. All pots were excavated at the end of the second year (28 Aug. 1999) and were returned to the laboratory, where leaf length and width of each seedling were measured again. Within 1 week of collection, living seedlings were carefully removed from the pot and washed. Seedlings were dried for 48 h at 80 °C and weighed. Total dry weights were compared among treatments for seedling at each age (first or second year).

To evaluate the effect of seedling size on subsequent survival, seedlings that emerged in 1998 and survived during the first season were classified into two groups at the end of the second season: alive or dead. Dry weights of the living first‐year seedlings were estimated from measures of leaf area as follows: ln dry weight = –1·35 + 0·67 × ln total leaf area (R = 0·772, P < 0·0001, n = 84). Individual leaf area was estimated using the following equation: leaf area = 0·66 + 0·56 × length × width (R = 0·998, P < 0·0001, n = 14). The estimated weights of the first‐year seedlings were compared between living and dead seedling classes.

In this paper, ‘F–F’ represents the treatment in which fellfield seeds were sown at the fellfield; ‘F–S’ represents the treatment in which fellfield seeds were sown at the snowbed; ‘S–F’ represents the treatment in which snowbed seeds were sown at the fellfield; and ‘S–S’ represents the treatment in which snowbed seeds were sown at the snowbed.

Germination experiment 1

The first experiment compared the temperature‐dependent germination patterns of fellfield and snowbed populations. Seeds experience a cold stratification during winter, so the germination responses of seeds subjected to a moist chilling treatment were compared. In 1998, fully mature seeds were harvested from more than 20 individuals at each of the five plots, and were then dried at room temperature (approx. 25 °C) for 1 month. Seeds from individuals growing in the same plot were bulked. Seeds were placed in 9‐cm‐diameter Petri dishes on filter papers moistened with 7 ml de‐ionized water for 2 months at 0 °C before being transferred to germination chambers. The Petri dishes were wrapped in aluminium foil to eliminate any light. After pre‐chilling, seeds were incubated at five alternating temperature regimes: 35/25, 30/20, 25/15, 20/10 and 15/5 °C at 12 h intervals. In every case, light (provided by cool‐white fluorescent lamps; photosynthetic photon flux density: 30 µmol m–2 s–1) and dark conditions were regulated at 12 h intervals with the light period coinciding with the higher temperature. Four replications of 25 seeds were assigned to each regime. Seeds were sown on a 0·3 % agar medium (01099‐11; KANTO Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan) in 9‐cm‐diameter Petri dishes sealed with parafilm to keep the media moist. Seeds were incubated for 40 d at each temperature regime. The number of germinated seeds was recorded each day, and any seeds that had germinated were removed every 5 d. Germination was defined as the emergence of the radicle through the seed coat. At the end of the incubation period, the viability of the remaining seeds was evaluated by crushing them; seeds with white, hard embryos were considered to be alive. The final germination percentage, in which dead seeds were eliminated from the calculation, was compared among plots.

Germination experiment 2

The second experiment examined the effects of fluctuating temperatures and water availability on germination. The extent of daily fluctuation and the daily mean temperature mimicked those of the soil surface in June (30/5 °C, 8/16 h, mean 13·3 °C) and July (30/10 °C, 8/16 h, mean 16·7 °C) in the fellfield. Seeds were exposed to three different water potentials under the two aforementioned temperature conditions. d‐Mannitol solution (M‐4125; Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) was used as an osmotic agent. Mannitol concentrations of 0, 0·02 and 0·04 mol l–1 were established. These concentrations approximate substrate water potentials of 0, –0·05 and –0·1 MPa, respectively (Swagel et al., 1997).

Fully mature seeds were collected from 120 randomly selected individuals, each of which produced more than four seeds, at each plot in 1999. Mean seed numbers (± s.d.) per plant were 7·1 ± 2·5, 7·8 ± 3·0, 12·5 ± 6·4, 10·4 ± 5·2 and 14·1 ± 6·7 at plots F1, F2, S1, S2 and S3, respectively. Seeds were kept at room temperature (approx. 25 °C) for 1 month before being exposed to a moist chilling treatment (as described above) for 6 months. Twenty individuals were assigned to each factorial combination of temperature and water potential. The germination experiment was conducted as described above. The final germination percentage was compared among the five populations in this experiment.

Statistical analysis

To determine whether seedling survivorship was influenced by source habitat (fellfield and snowbed) or germination time (June, July, August and September), the survival curves of seedlings that emerged in 1998 were compared over 2 years at each habitat using the Kaplan–Meier procedure of survival analysis. This procedure estimates survival functions from survival periods of seedlings. A Mantel–Cox test was performed for homogeneity of survival across the source habitats, and a Mantel test across germination times. The survival period was defined as the number of days between seedling emergence and death. Seedlings that survived until the end of the observation period were regarded as censored data. Winter dormancy, which was defined as the period between 1 October and 30 May at the fellfield site and from 1 October to the day of snow disappearance at the snowbed, was excluded from the calculation of survival period, and seedlings that died during overwintering were regarded as being alive until 30 September. Differences in dry weight of seedlings among treatments were tested by one‐way ANOVA. The Scheffé test was used for multiple comparison tests among means. The size of dead and living seedlings was compared using the unpaired t‐test. Data were log‐transformed before statistical analysis to minimize the heterogeneity of variance.

As the data type of germination is binomial, logistic regressions were used to estimate the effects of temperature conditions, water potentials and plots on the probabilities of seed germination. The five temperature conditions, ranging from 15/5 to 35/25 °C, were regarded as a continuous variable from 1 to 5, respectively, for the first experiment. Temperature conditions (30/5 and 30/10 °C) were included as a categorical variable and water potentials (0, –0·05 and –0·1 MPa) as a continuous variable in the analyses for the second experiment. Plots (F1, F2, S1, S2 and S3) were included as a categorical variable for both germination experiments.

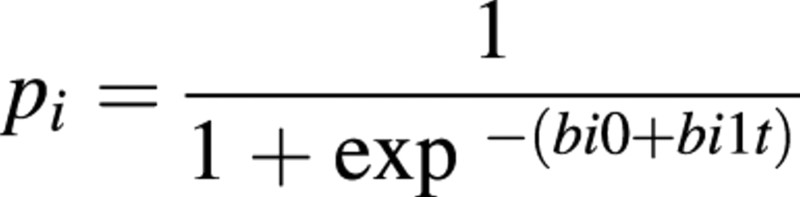

The logistic regression model used in this study was:

where pi is the probability of germination for the ith plot, bi0 and bi1 are the regression coefficients for the ith plot and t is temperature. A parameter set of bi0 and bi1 was estimated using a maximum likelihood method for binomial distribution for each plot, so that the full model has five parameter sets. When a significant contribution of a plot to the model was detected, differences between plots were investigated.

Because the full model may include some parameter sets for potential exclusion, model selection was carried out. The number of parameter sets was minimized by merging plot data sets, thus maximizing the ‘goodness‐of‐fit’ given by the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC). The AIC was evaluated to select the best model that fitted the data adequately (Burnham and Anderson, 1998). The AIC for a model is given by the following formula:

AIC = –2 log Lmax + 2 K

where Lmax is the maximized likelihood for the model and K is the number of parameters estimated in the model (e.g. K = 2 × 5 = 10 for the full model). The model with the lowest AIC is the best approximating model for the data.

The Mantel–Cox test was performed using STATISTICA version 5·5 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). The maximum likelihood and AIC calculation were performed using logistic.pm (http://hosho.ees.hokudai.ac.jp/∼kubo/ml/logistic/). All other statistical analyses were performed using StatView version 5·0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Environmental conditions

The timing of snowmelt at each snowbed plot fluctuated amongst the observation years (1997–1999). In comparison with the other years, there was very little snow and a warm spring in 1998, and the snow disappeared from each snowbed plot about 1 month earlier than usual. Snow had disappeared by 1 July, 8 June and 20 July in 1997, 1998 and 1999, respectively, at the S2 plot. Both fellfields were free from snow cover after late May every year.

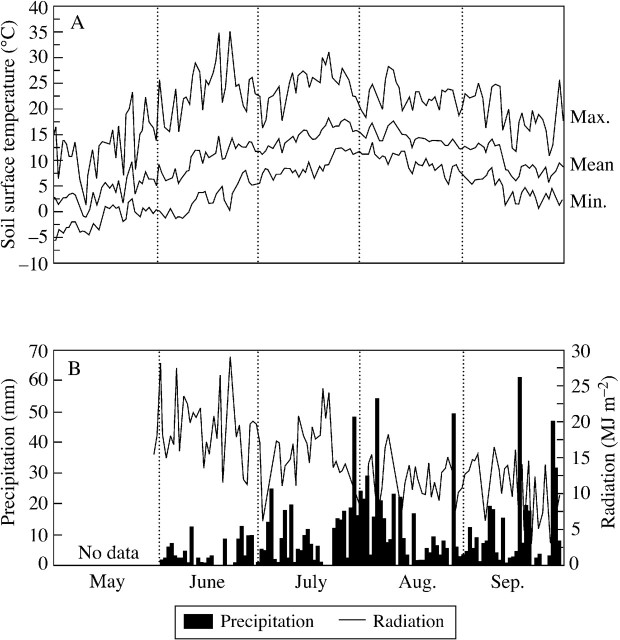

The mean temperature of the soil surface measured at the F1 plot increased gradually from May to June, reaching a maximum in July and August (Fig. 1). The daily fluctuation of the soil surface temperature was maximal in June when the daily temperature varied from 5 to 30 °C on clear, sunny days. The amplitude of daily fluctuation decreased as the season progressed. In addition, June was the driest month during the growing season (Fig. 1). The soil surface temperature at the snowbed remained at zero until snowmelt, then showed a similar seasonal transition as that at the fellfield.

Fig. 1. Seasonal transition of daily mean, maximum and minimum soil surface temperature (A), and daily accumulation of precipitation and global radiation (B) at the F1 plot. Values are means of 3 years from 1997 to 1999.

Seedling emergence in the field

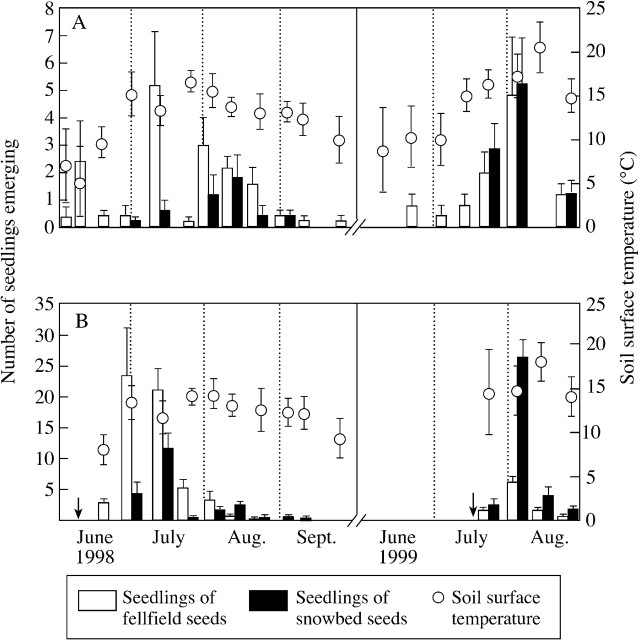

Patterns of seedling emergence differed between replanted seeds and transplanted seeds at both habitats (Fig. 2). Only seven F–F seedlings (1·4 %) and one F–S seedling (0·2 %) emerged within the first year of sowing (1997). The majority of emergence events occurred the following year (data from June 1998 are shown in Fig. 2). At the F1 plot in 1998, the emergence of F–F seedlings started in early June, when the mean soil surface temperature was only 5 °C, and continued throughout the season. S–F seedlings did not emerge until early July when the mean soil temperature had reached approx. 15 °C, and most seedling emergence was concentrated during early and mid‐August. At the S2 plot in 1998, the emergence of F–S seedlings started in mid‐June, soon after snow disappearance, but S–S seedlings started to emerge in early July. For both F–S and S–S seedlings, emergence was concentrated during early to mid‐July at the S2 plot. In 1999, seedling emergence began later than in the previous year at the F1 plot, but, as in 1998, the seeds derived from the fellfield germinated earlier than those from the snowbed. Snow at the S2 plot disappeared in late July 1999 when the mean ground temperature increased to around 15 °C, and the emergence of F–S and S–S seedlings occurred at similar times. In total, over the 3 years, more fellfield (140 F–F) than snowbed seeds (70 S–F) emerged at the F1 plot. At the S2 plot, twice as many fellfield seedlings (227) emerged than snowbed seedlings (108) in 1998. However, the number of germinated seeds from the fellfield decreased in the following year, so that the total number of seedlings that emerged was similar for fellfield (274 F–S) and snowbed seeds (275 S–S) at the S2 plot.

Fig. 2. Seasonal patterns of seedling emergence per pot and seasonal changes in soil surface temperature at the fellfield (A) and snowbed (B). Mean (± s.e.) seedling emergence is shown for five pots. Mean temperatures (± s.d.) are shown for the 10 d prior to observations. Arrows indicate the time of snowmelt at the snowbed.

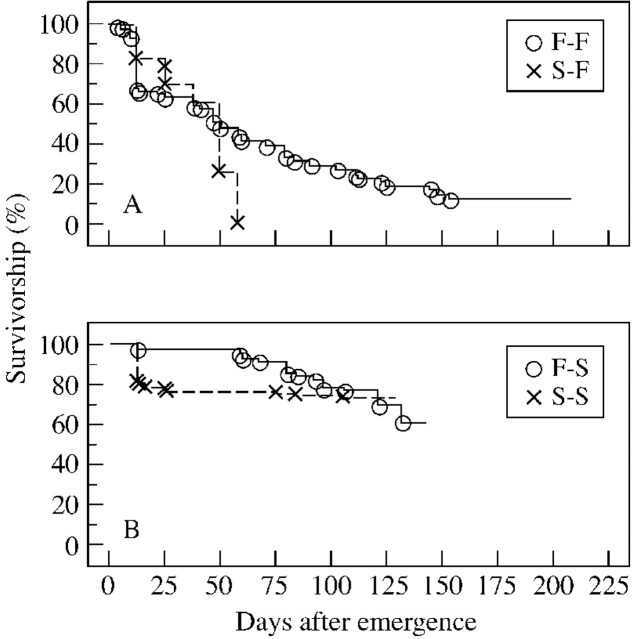

The percentage survivorship of seedlings that emerged in 1998 differed significantly between F–F and S–F seedlings (x2 = 6·18, P < 0·05, d.f. = 1; Fig. 3). F–F seedlings had low percentage survivorship (10 %), and none of the S–F seedlings survived to the beginning of the second growing season at the fellfield. On the other hand, there was no significant difference in survivorship between F–S and S–S seedlings (x2 = 0·08, P = 0·78, d.f. = 1; Fig. 3) at the end of the second season at the snowbed, with survivorship standing at approx. 70 % for both types.

Fig. 3. Survival curves for seedlings germinated in 1998 over 2 years at the fellfield (A) and snowbed (B). Cumulative values for all pots are shown. Observations were made from the time of germination to late August 1999. See text for treatment descriptions.

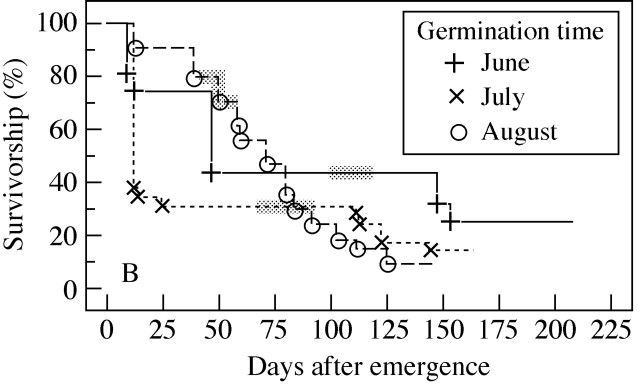

Survival curves of F–F seedlings that emerged in 1998 differed among emergence cohorts (June, July and August) at the fellfield (x2 = 6·39, P < 0·05, d.f. = 2; Fig. 4). The seedlings that germinated in September were not included in this analysis because of the small sample size (n = 4). Seedlings that emerged between June and July had high mortality in the first year relative to those seedlings that emerged in August. On the other hand, seedlings that emerged in August had high mortality in the second year (after overwintering). In other words, seedlings that emerged earlier (June and July) yielded a higher proportion of plants that overwintered than did seedlings that emerged later (August) in the fellfield. Because most emergence of S–F seedlings was concentrated in August, survivorship was not compared between seedling cohorts. Survivorship curves at the snowbed did not differ significantly among seedlings cohorts, and survivorship percentages were high throughout the growing season (x2 = 1·94, P = 0·16, d.f. = 1, between July and August cohorts for F–S seedlings; x2 = 2·57, P = 0·11, d.f. = 1, between July and August cohorts for S–S seedlings).

Fig. 4. Survival curves are shown for seedlings that germinated at different times in 1998 at the F1 plot. The seedlings were derived from fellfield seeds sown at the fellfield (F–F). Shading shows the end of the first growing season.

There was no significant difference in the dry weight of first year seedlings amongst treatments (one‐way ANOVA, F3,96 = 0·94, P = 0·42). Mean dry weights (± s.d.) per first‐year seedling were 1·8 ± 1·3 (n = 17), 1·2 ± 0·7 (n = 30), 1·0 ± 0·5 (n = 23) and 1·1 ± 0·6 mg (n = 30) for the F–F, S–F, F–S and S–S treatments, respectively. However, a significant difference was detected in the second year (F2,86 = 45·87, P < 0·0001), by which time the biomass of F–F seedlings was three to five times greater (10·3 ± 4·6 mg, n = 11) than that of plants from other treatments. Second‐year F–S seedlings had a smaller biomass (1·8 ± 0·5 mg, n = 47) than did S–S seedlings (2·9 ± 1·1 mg, n = 31). In the comparison of seedling size in the first season, seedlings that survived until the end of the second season had a significantly greater biomass (1·57 ± 0·57 mg, n = 11) than did those that died (0·87 ± 0·41 mg, n = 37) in the F–F treatment (t‐test, t = –4·54, P < 0·0001). The size of S–F seedlings that emerged in 1998 (0·78 ± 0·21 mg, n = 17), and which completely failed to overwinter, was similar to that of F–F seedlings that died, indicating that plant size is a critical factor for overwintering at the fellfields. There were no significant differences in seedling size between living and dead seedlings at the snowbed (P > 0·1 in both F–S and S–S seedlings).

Germination experiment 1

There were significant differences in germination percentages among the plots (x2 = 16·52, P < 0·01, d.f. = 4), among the temperature regimes (x2 = 1540·68, P < 0·0001, d.f. = 1), and for the interaction (x2 = 29·90, P < 0·0001, d.f. = 4) in the likelihood‐ratio test. Seeds from every plot had germination percentages greater than 80 % under warm temperature conditions (35/25 °C and 30/20 °C, Table 1). Germination percentages were lower under cooler conditions than in the 30/20 °C regime, and those in the 15/5 °C regime were almost zero. Seeds from the F1 plot had the highest germination percentages in every temperature regime. Seeds from the S3 plot had the lowest germination in the 25/15 °C and 20/10 °C regimes, but they showed higher germinability than seeds from the other two snowbed plots under warm temperature conditions. The lowest AIC value was obtained when it was assumed that the curves of the F2 and S1 plots were similar and others were different (AIC = 197·16). Therefore, habitat differences between the fellfield and the snowbed were not clear for the temperature regimes of this experiment. The rates of germination increased similarly with an increase in temperature in all populations.

Table 1.

Germination percentages (mean ± s.e.) for 40 d under various temperature conditions

| Plot | |||||

| Temperature (°C) | F1 | F2 | S1 | S2 | S3 |

| 35/25 | 97·0 ± 1·5 | 95·2 ± 0·9 | 91·3 ± 4·8 | 82·9 ± 2·0 | 95·0 ± 0·9 |

| 30/20 | 98·7 ± 1·3 | 88·9 ± 4·2 | 88·6 ± 1·1 | 85·3 ± 2·0 | 93·2 ± 0·9 |

| 25/15 | 57·8 ± 3·5 | 31·3 ± 4·2 | 38·5 ± 4·1 | 35·1 ± 6·3 | 21·6 ± 3·8 |

| 20/10 | 30·5 ± 8·2 | 21·5 ± 1·8 | 21·3 ± 4·8 | 17·6 ± 5·0 | 5·0 ± 1·9 |

| 15/5 | 0·0 ± 0·0 | 0·0 ± 0·0 | 0·0 ± 0·0 | 1·0 ± 1·0 | 0·0 ± 0·0 |

n = 4 in all plots, except F1 where n = 3 due to the shortage of seeds.

Germination experiment 2

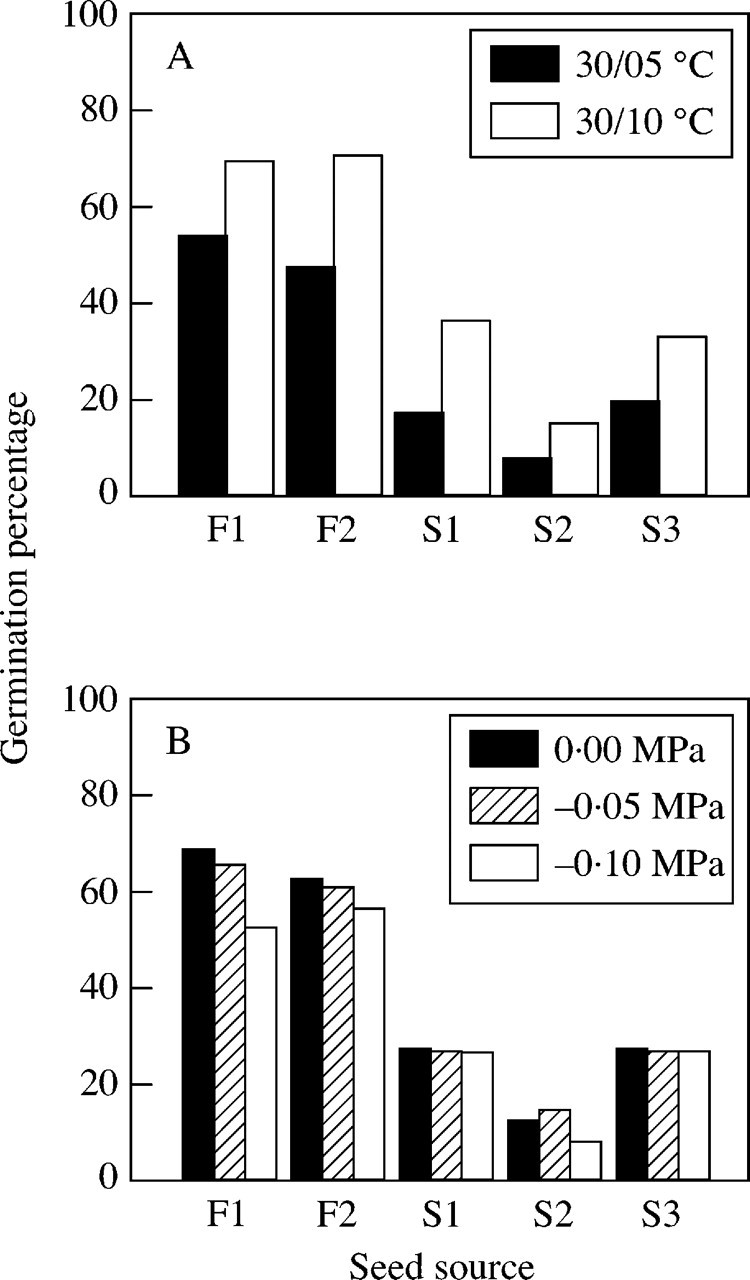

There was a significant difference in germination percentages among the plots (x2 = 811·81, P < 0·0001, d.f. = 4). Germination percentages were higher in the 30/10 °C regime than in the 30/5 °C regime (x2 = 211·11, P < 0·0001, d.f. = 1), and lower under conditions of low water potential (x2 = 11·60, P < 0·001, d.f. = 1). Significant interactions were detected between plot and water potential (x2 = 13·38, P < 0·01, d.f. = 4), and among the three main effects (x2 = 42·90, P < 0·0001, d.f. = 4). Germination percentages of seeds from the F1 and S2 plots were reduced by the –0·1 MPa treatment, but those from other plots were not influenced by the water potentials (Fig. 5). Interactions between plot and temperature (x2 = 4·91, P > 0·1, d.f. = 4), and between temperature and water potential (x2 = 0·63, P < 0·1, d.f. = 1) were not significant. The lowest AIC value was obtained when we assumed that the curves of the S1 and S3 plots were similar and others were different (AIC = 245·05). In general, germination percentages of seeds from the fellfields were higher than those from the snowbeds under both temperature conditions.

Fig. 5. Comparisons of germination responses to fluctuating temperatures of different amplitudes (A) and different water potentials (B) for seeds of P. matsumurae from five plots.

DISCUSSION

Seedling survival in the field

Different patterns of seedling emergence were detected between the fellfield and snowbed populations of P. matsumurae. Seeds derived from the fellfield population started to germinate earlier than did those from the snowbed population, and the germination of fellfield seeds occurred throughout the season at the fellfield. The timing of seedling emergence greatly affected subsequent survival at the fellfield. In the first year, seedlings that emerged in August had a higher percentage survivorship than did those that emerged in June and July, because June and early July are dry months, and frost occurs unpredictably in the early part of the season. In contrast, percentage survivorship overwinter was greatest for seedlings that emerged early in the season. Early‐emerging seedlings achieved a larger size prior to overwintering owing to their longer growing period.

Phenotypic variation in the timing of germination has been reported for many species (Kalisz, 1986; Kachi and Hirose, 1990; Philippi, 1993; Clauss and Venable, 2000). Some studies have demonstrated a trade‐off between low survivorship and high reproductive output for early seedling emergence in several annual species (Arthur et al., 1973; Marks and Prince, 1981; González‐Astorga and Núñez‐Farfán, 2000). The timing of seedling emergence in P. matsumurae may relate to a trade‐off between survivorship during the growing season and over the first winter at the fellfield. The occurrence of sporadic seedling emergence throughout the growing season implies that the relative importance between summer and winter survivorship is variable in time and space, reflecting the unpredictable environmental conditions at fellfields. Such fluctuations of selection forces may contribute to maintaining genetic and phenotypic variation (Van Buskirk et al., 1997).

At the snowbeds, snowbed seeds started to germinate when the soil surface temperature reached 13–15 °C, even when snowmelt occurred unexpectedly earlier than usual (e.g. in 1998). Even late‐emerging seedlings could overwinter successfully despite the extremely short growing period here. This indicates that the short growing period might not be a crucial factor affecting seedling establishment in this species at the snowbed. In contrast, the snowbed seeds had low germination percentages and could not survive the first winter when they were sown at the fellfield. Since the snowbed seeds tended to germinate later in the season than did those from the fellfield, most snowbed seedlings might not have attained the minimum critical size necessary to survive the severe winter at the fellfield.

Germination characteristics

Habitat‐specific differences were not recognized in the first germination experiment. However, under fluctuating temperatures that simulated field conditions, distinct differences in the germination percentages were apparent between fellfield and snowbed populations. It is known that diurnal fluctuations in temperature stimulate germination of seeds in many species (Thompson and Grime, 1983; Schütz and Rave, 1999), including alpine species (Sayers and Ward, 1966). The ecological significance of germination stimulation by fluctuating temperature has generally been regarded as a gap‐detection and depth‐sensing mechanism for plants forming seed pools (Fenner, 1985). Furthermore, it is available as a season‐sensing system for temperate plants because the diurnal fluctuation of the soil surface temperature is large in the spring before dense vegetation covers the ground of deciduous forests or grasslands. Washitani and Kabaya (1988) indicated that the effective alternating temperature responsible for breaking seed dormancy in Primula sieboldii corresponded with the natural temperature regime in the species’ habitat in spring. At the fellfields, the daily temperature of the soil surface fluctuated intensely in June: the maximum daily ground temperature sometimes rose to over 30 °C on sunny days, but the night‐time temperature fell to below zero early in the season. Widely fluctuating temperatures are uncommon at snowbed habitats because the ground is usually covered by thick snow in June. The stimulation of seed germination by fluctuating temperatures may be a mechanism for fellfield seeds to germinate early in the season. Snow usually disappears from snowbed habitats when the air temperature reaches its maximum level; thus, the response of germination to temperature fluctuation may not be important for snowbed seeds.

Germination percentages were reduced slightly in the low water potential treatments only in the seeds from the F1 and S2 plots. Oberbauer and Miller (1982) examined the effect of water potential on seed germination for 17 arctic species, and indicated that a water potential of –1 bar (–0·1 MPa) was low enough to restrict germination of species growing at dry sites. Seeds of herbaceous species collected from wetland habitats in England showed great reductions in germination at soil water potentials below –0·05 MPa, whereas those of some species from dry habitats germinated even at –1·0 or –1·5 MPa (Evans and Etherington, 1990). Thus, there are large variations in the sensitivity to water potential among plants from different habitats. Although moisture availability is generally lower at fellfields than at snowbeds (Miller, 1982; pers. comm.), a difference of water availability for germination between the habitats was not clear in this experiment. Further experiments involving lower water potentials may reveal a significant pattern.

Implications for gene flow between the habitats

Separation of the flowering seasons owing to the different timing of snowmelt should restrict gene flow via pollination between the fellfield and snowbed habitats. However, because the transition from fellfields to snowbeds occurs within a small geographical area, seed dispersal may be possible between the habitats (Stanton et al., 1997). If selection pressures operate differently through the stages of germination, seedling establishment, growth and reproduction, the genetic composition of the population of adult plants may differ from that of the seed population within a habitat. Recent studies have demonstrated genetic differences between seeds in the soil and the growing plants (Cabin et al., 1998), between seeds and seedlings (Cabin, 1996), and between seedlings and adult plants (Tonsor, et al., 1993; Stanton et al., 1997). Therefore the probability of seed dispersal and the subsequent successful establishment of seedlings are crucial for gene flow between the habitats (Fenster, 1991a, b; Stanton et al., 1997; Nathan and Muller‐Landau, 2000). According to the reciprocal sowing experiment in this study, no seedlings from the snowbed population could establish at the fellfield, indicating the difficulty in migration from snowbeds to fellfields. Although seedlings from the fellfield population could survive for at least 2 years at the snowbed, the second‐year seedlings had a significantly smaller biomass than that of native snowbed seedlings. A study of Dryas octopetala ecotypes indicated that snowbed plants were able to withstand the diminished light availability associated with increased competition better than fellfield plants (McGraw, 1985). If this is the case in P. matsumurae, then fellfield plants may have a reduced fitness compared with that of snowbed plants, or may be excluded from the snowbed habitat in the long term.

Genetic factors and the environment of the mother plant during the time of seed maturation are major factors controlling variation in the germination requirement within species (Baskin and Baskin, 2001). Although more detailed research is necessary to separate maternal effects from inherent genetic differences, our results indicate that selective pressures work differently on time to germination, and that there is intraspecific variation in the germination response between fellfield and snowbed populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Takashi Kohyama, Shiro Tsuyuzaki, Hiromi Fukuda, Shizuo Suzuki and Tetsuya Kasagi for valuable suggestions in planning and discussion; Kengo Yoshida, Kenji Narita, Mikio Sukeno, Tomokazu Tani and Toru Takeuchi for help with fieldwork; Miho Ajima for useful comments on this manuscript, and Takuya Kubo for help in data analyses. This paper was improved by the comments of Susan Meyer. The study was supported, in part, by a Grant‐in‐Aid (10740355) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture to G.K.

Supplementary Material

Received: 18 April 2002; Returned for revision: 24 July 2002; Accepted: 26 September 2002 Published electronically: 13 November 2002

References

- ArthurAE, Gale JS, Lawrence MJ.1973. Variation in wild populations of Papaver dubium VII. Germination time. Heredity 30: 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- BaskinCC, Baskin JM.2001. Seeds: ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination. San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- BaskinJM, Baskin CM.1979. Studies on the autecology and population biology of the weedy monocarpic perennial, Pastinaca sativa Journal of Ecology 67: 601–610. [Google Scholar]

- BecksteadJ, Meyer SE, Allen PS.1996. Bromus tectorum seed germination: between‐population and between‐year variation. Canadian Journal of Botany 74: 875–882. [Google Scholar]

- BellKL, Bliss LC.1980. Plant reproduction in a high arctic environment. Arctic and Alpine Research 12: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- BillingsWD, Bliss LC.1959. An alpine snowbank environment and its effects on vegetation, plant development, and productivity. Ecology 40: 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- BillingsWD, Mooney HA.1968. The ecology of arctic and alpine plants. Biological Reviews 43: 481–529. [Google Scholar]

- BurnhamPB, Anderson, DR.1998. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information‐theoretic approach. New York: Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- CabinRJ.1996. Genetic comparisons of seed bank and seedling populations of a perennial desert mustard, Lesquerella fendleri Evolution 50: 1830–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CabinRJ, Mitchell RJ, Marshall DL.1998. Do surface plant and soil seed bank populations differ genetically? A multipopulation study of the desert mustard Lesquerella fendleri (Brassicaseae). American Journal of Botany 85: 1098–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClaussMJ, Venable DL.2000. Seed germination in desert annuals: an empirical test of adaptive bet hedging. American Naturalist 155: 168–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EvansC, Etherington JR.1990. The effect of soil water potential on seed germination of some British plants. New Phytologist 115: 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FennerM.1985. Seed ecology. London: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- FensterCB.1991a Gene flow in Chamaecrista fasciculata (Leguminosae). I. Gene dispersal. Evolution 45: 398–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FensterCB.1991b Gene flow in Chamaecrista fasciculata (Leguminosae). II. Gene establishment. Evolution 45: 410–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González‐AstorgaJ, Núñez‐Farfán J.2000. Variable demography in relation to germination time in the annual plant Tagetes micrantha Cav. (Asteraceae). Plant Ecology 151: 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- GrovesRH, Hagon MW, Ramakrishnan PS.1982. Dormancy and germination of seed of eight populations of Themeda australis Australian Journal of Botany 30: 373–386. [Google Scholar]

- KachiN, Hirose T.1990. Optimal time of seedling emergence in a dune‐population of Oenothera glazioviana Ecological Research 5: 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- KaliszS.1986. Variable selection on the timing of germination in Collinsia verna (Scrophulariaceae). Evolution 40: 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KörnerC.1999. Alpine plant life: functional plant ecology of high mountain ecosystems. Berlin: Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- KudoG.1991. Effects of snow‐free period on the phenology of alpine plants inhabiting snow patches. Arctic and Alpine Research 23: 436–443. [Google Scholar]

- McGrawJB.1985. Experimental ecology of Dryas octopetala ecotypes. III. Environmental factors and plant growth. Arctic and Alpine Research 17: 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliamsEL, Landers RQ, Mahlstede JP.1968. Variation in seed weight and germination in populations of Amaranthus retroflexus L. Ecology 49: 290–296. [Google Scholar]

- MarikoS, Koizumi H, Suzuki J, Furukawa A.1993. Altitudinal variations in germination and growth responses of Reynoutria japonica populations on Mt Fuji to a controlled thermal environment. Ecological Research 8: 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- MarksM, Prince S.1981. Influence of germination date on survival and fecundity in wild lettuce Lactuca serriola Oikos 36: 326–330. [Google Scholar]

- MarutaE.1976. Seedling establishment of Polygonum cuspidatum on Mt. Fuji. Japanese Journal of Ecology 26: 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- MarutaE.1983. Growth and survival of current‐year seedlings of Polygonum cuspidatum at the upper distribution limit on Mt. Fuji. Oecologia 60: 316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MarutaE.1994. Seedling establishment of Polygonum cuspidatum and Polygonum weyrichii var. alpinum at high altitudes of Mt Fuji. Ecological Research 9: 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- MeyerSE, Monsen SB.1991. Habitat‐correlated variation in mountain big sagebush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana) seed germination patterns. Ecology 72: 739–742. [Google Scholar]

- MeyerSE, Allen PS, Beckstead J.1997. Seed germination regulation in Bromus tectorum (Poaceae) and its ecological significance. Oikos 78: 475–485. [Google Scholar]

- MeyerSE, Kitchen SG, Carlson SL.1995. Seed germination timing patterns in intermountain Penstemon (Scrophulariaceae). American Journal of Botany 82: 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- MillerPC.1982. Environmental and vegetational variation across a snow accumulation area in montane tundra in central Alaska. Holarctic Ecology 5: 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- NathanR, Muller‐Landau HC.2000. Spatial patterns of seed dispersal, their determinants and consequences for recruitment. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 15: 278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NishitaniS, Masuzawa T.1996. Germination characteristics of two species of Polygonum in relation to their altitudinal distribution on Mt Fuji, Japan. Arctic and Alpine Research 28: 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- OberbauerS, Miller PC.1982. Effect of water potential on seed germination. Holarctic Ecology 5: 218–220. [Google Scholar]

- OnipchenkoVG, Semenova GV, Maarel E.1998. Population strategies in severe environments: alpine plants in the northwestern Caucasus. Journal of Vegetation Science 9: 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- PhilippiT.1993. Bet‐hedging germination of desert annuals: beyond the first year. American Naturalist 142: 474–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SayersRL, Ward RT.1966. Germination responses in alpine species. Botanical Gazette 127: 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- SchützW, Rave G.1999. The effect of cold stratification and light on the seed germination of temperate sedges (Carex) from various habitats and implications for regenerative strategies. Plant Ecology 144: 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- StantonML, Galen C, Shore J.1997. Population structure along a steep environmental gradient: consequences of flowering time and habitat variation in the snow buttercup, Ranunculus adoneus Evolution 51: 79–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SwagelEN, Bernhard AVH, Ellmore GS.1997. Substrate water potential constraints on germination of the strangler fig Ficus aurea (Moraceae). American Journal of Botany 84: 716–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ThompsonK, Grime JP.1983. A comparative study of germination responses to diurnally‐fluctuating temperatures. Journal of Applied Ecology 20: 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- TonsorSJ, Kalisz S, Fisher J, and Holtsford TP.1993. A life‐history based study of population genetic structure: seed bank to adults in Plantago lanceolata Evolution 47: 833–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van BuskirkJ, McCollum SA, and Werner EE.1997. Natural selection for environmentally induced phenotypes in tadpoles. Evolution 51: 1983–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VeraML.1997. Effects of altitude and seed size on germination and seedling survival of heathland plants in north Spain. Plant Ecology 133: 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- WashitaniI, Kabaya H.1988. Germination responses to temperature responsible for the seedling emergence seasonality of Primula sieboldii E. morren in its natural habitat. Ecological Research 3: 9–20. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.