Abstract

Musa L. (Musaceae) is currently separated into five sections (Musa, Rhodochlamys, Callimusa, Australimusa and Ingentimusa) based on chromosome numbers and morphological characters. However, the validation of this classification system is questioned due to the common occurrence of hybridizations across sections and the system not accommodating anomalous species. This study employed amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) in a phenetic examination of the relationships among four sections (material of sect. Ingentimusa was not available) to evaluate whether their genetic differences justify distinction into separate groups. Using eight primer combinations, a total of 276 bands was scored, of which 275 were polymorphic. Among the monomorphic bands, 11 unique markers were identified that revealed the distinct separation of the 11‐chromosome species from the 10‐chromosome species. AFLP results suggest that species of sect. Rhodochlamys should be combined into a single section with species of sect. Musa, and likewise for species of sect. Australimusa to be merged with those of sect. Callimusa.

Key words: Banana, Musa, Musaceae, section, Rhodochlamys, Callimusa, Australimusa, AFLP, DNA fingerprinting

INTRODUCTION

The first subgeneric classification of Musa s.l. began with three subgenera Physocaulis, Eumusa and Rhodochlamys (Sagot, 1887; Baker, 1893). Later, Cheesman (1947) laid the foundation for the grouping of banana species into four sections. He recognized subgenus Physocaulis as a distinct genus, Ensete with a chromosome number n = x = 9. Within Musa s.s., he redefined subgenera Eumusa (now sect. Musa) and Rhodochlamys as two separate sections, and described an additional two sections, Australimusa and Callimusa. Cheesman (1947) also redistributed the species among the four sections to produce more homogenous groups.

Species of sections Musa and Rhodochlamys share common characteristics, possessing the same chromosome number (n = x = 11) and having bracts that are generally sulcate, glaucous and that become revolute on fading (Cheesman, 1947). This contrasts with species of sections Australimusa and Callimusa, which have chromosome number n = x = 10, and bracts that are smooth, polished on the outside and that do not become revolute on fading.

Species of sect. Musa are distinguished from those of sect. Rhodochlamys in being large plants, 3 m or more tall, with pendent inflorescences with dull coloured bracts, many flowers in two series per bract and reflexed fruits. In contrast, species of sect. Rhodochlamys are generally smaller in stature (less than 3 m), have erect inflorescences with brightly coloured bracts with a few flowers in a single series and the fruits are not reflexed. Species of sect. Callimusa are separated from those of sect. Australimusa by their unique seeds, which are cylindrical or barrel‐shaped and possess a large apical chamber. In contrast, seeds of species of sect. Australimusa are similar to those of species in sect. Musa and Rhodochlamys, being subglobose or dorsiventrally compressed and possessing a small apical chamber.

Subsequent authors have followed these groupings, although Simmonds (1960) pointed out that three species (Musa beccarii N.W. Simmonds, M. lasiocarpa Franch. and M. ingens N.W. Simmonds) did not conform entirely to any of the existing sections. Since then, Wu (cited in Li, 1978) has placed M. lasiocarpa in its own monotypic genus, Musella, and Argent (1976) has created a new section, sect. Ingentimusa for M. ingens, which has a chromosome number of n = x = 14. Describing two new species from Borneo, M. monticola [Hotta ex] Argent and M. suratii Argent, Argent (2000) was unable to place them with any certainty into any section on morphological grounds. The placement of these two species and that of M. beccarii was discussed in Wong et al. (2001a).

There is a need to reassess the validity and usefulness of these sections in Musa because several authors have drawn attention to difficulties in placing species within existing sections (Simmonds, 1960; Argent, 1976), and the status of sect. Rhodochlamys as a valid section has been questioned by Cheesman (1947), Simmonds (1962), Shepherd (1990) and Jarret and Gawel (1995).

Taxonomic studies in Musa have been conducted using a wide array of techniques, such as morphological characters (Simmonds, 1962; Simmonds and Weatherup, 1990), isozymes (Bhat et al., 1992), cytogenetics (Cheesman, 1947; Shepherd, 1959; Osuji et al., 1997), molecular cytogenetics (Osuji et al., 1998), intergenic spacers (Lanaud et al., 1992), restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) (Gawel and Jarret, 1991; Gawel et al., 1992), random amplified polymorphic DNA markers (RAPDs) (Howell et al., 1994), inter simple sequence repeats (ISSRs) (Godwin et al., 1997) and microsatellites (Grapin et al., 1998). Although these have provided a general understanding of Musa classification, the question of the validity of the sectional classification system is still unresolved. Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) (Vos et al., 1995) is a robust and reliable molecular technique recently employed in many plant systematic studies, involving, for instance, lettuce (Hill et al., 1996), soybean (Powell et al., 1996), rice (Aggarwal et al., 1999), Caladium (Loh et al., 1999, 2000c) and bamboo (Loh et al., 2000a). Levels of polymorphism in Musa were shown to be high when analysed using AFLP, and the technique was the most effective for genetic diversity analysis as shown in the studies of Crouch et al. (1999), Loh et al. (2000b) and Wong et al. (2001a, b).

The problems highlighted reveal the shortcomings of the current state of Musa classification. Hence, this study employs AFLPs in a phenetic examination of the relationships among sections Musa, Rhodochlamys, Callimusa and Australimusa of genus Musa, and evaluates whether genetic differences among the sections are sufficiently significant or distinct to justify maintaining the four sections as separate groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

A total of 21 Musa species and subspecies was examined, with sample sizes ranging from three to five (Table 1). Two species of Ensete, E. superbum (Roxb.) Cheesm. and E. glaucum (Roxb.) Cheesm. were included as reference taxa, for comparison with Musa. The material included representatives from four sections of Musa (sect. Ingentimusa was excluded due to lack of available material) of both wild and cultivated origin and from a variety of introductions. Samples were collected from wild populations, the Singapore Botanic Gardens (Singapore), the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (UK) and the Agricultural Park at Tenom (Sabah, Malaysia). Voucher specimens were deposited in the herbaria at Singapore Botanic Gardens and the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

Table 1.

Species of Musa and Ensete studied

| Taxon | Accession No. | Source |

| Ensete superbum (Roxb.) Cheesm.*(8) | AR200/94‐96‐8474 | RBG/SBG |

| Ensete glaucum (Roxb.) Cheesm. (11) | AR215 | RBG |

| Musa sect. Musa | ||

| M. acuminata Colla ssp. truncata Ridl. (1) | RK4718/RK4889 | CH/FH |

| M. acuminata Colla ssp. malaccensis (Ridl.) Simmonds (2) | RK4890/CW1‐5 | KKB/T |

| M. acuminata Colla ssp. burmanica Simmonds (12) | AR214 | RBG |

| M. acuminata Colla ssp. siamea Simmonds (9) | GA s.n. (siamea) | RBG |

| M. balbisiana Colla (3) | AR s.n./GA s.n. (balbisiana) | RBG/CI |

| M. nagensium Prain (14) | 19991679A | RBG |

| M. sikkimensis Kurz (15) | 19972089 | RBG |

| M. itinerans E. E. Cheesm. (7) | AR201 | RBG |

| Musa sect. Rhodochlamys | ||

| M. laterita E. E. Cheesm. (10) | GA s.n. (laterita) | RBG |

| M. ornata Roxb. (6) | 19961732/101‐92‐45/AL5 | RBG/SBG/AP |

| M. velutina H. Wendl & Drude (18) | 19702121 / 19980690 | RBG/SBG |

| Musa sect. Callimusa | ||

| M. suratii Argent (21) | AL6 | AP |

| M. borneensis Becc. (19) | GA s.n. (borneensis)/19992248/AL2 | RBG/SBG/AP |

| M. campestris Becc. (16) | 19773441/AL3 | RBG/AP |

| M. coccinea Andr. (13) | AR213 | RBG |

| M. violascens Ridl. (5) | RK4876 | FH |

| M. gracilis Holttum (23) | RK5088 | CR |

| Musa sect. Australimusa | ||

| M. textilis Née (4) | AL 7 | AP |

| M. jackeyi Hill (22) | 19990218 | SBG |

| M. beccarii Simmonds (20) | AL 1 | AP |

| M. monticola [Hotta ex] Argent (17) | 19891874/AL 4 | RBG/AP |

AP, Agricultural Park, Tenom, Sabah, Malaysia; CH, Cameron Highlands, Malaysia; CI, Camiguin Island, Philippines; CR, Chukai River, Trengganu, Malaysia; FH, Fraser’s Hill, Malaysia; KKB, Kuala Kubu Baru, Selangor, Malaysia; RBG, Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh; SBG, Singapore Botanic Gardens, Singapore; T, Tapah, Perak, Malaysia.

* See Table 4.

Leaf tissue was used for AFLP analysis. Leaves were surface sterilized following the procedure described in Zhang et al. (1997). Briefly, leaves collected were swirled in 95 % ethanol for 1 min, 5 % bleach (NaOCl) for 5 min and then re‐immersed in fresh 95 % ethanol for 30 s, after which they were blotted dry and stored in sealed plastic bags at –80 °C until required for DNA extraction.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted using the CTAB method according to Reichardt and Rogers (1993). Briefly, leaf tissue was pulverized using liquid nitrogen prior to the addition of 4 ml Solution I [2 % w/v CTAB (Sigma), 100 mm Tris‐HCl, 20 mm EDTA, 1·4 m NaCl, pH 8·0] per gram of leaf tissue and incubated for 60 min at 65 °C. The homogenate was then extracted with an equal volume of chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24 : 1) and centrifuged at 12 000 rpm for 5 min. The upper aqueous phase was recovered and incubated with 1/10 volume Solution II (10 % w/v CTAB, 0·7 m NaCl), pre‐warmed to 65 °C. The aqueous phase was then extracted with one volume of chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24 : 1) and recovered as before. To the recovered aqueous phase, one volume of Solution III (1 % w/v CTAB, 50 mm Tris‐HCl, 10 mm EDTA, pH 8·0) was added and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The mixture was centrifuged for 5 min at 3500 rpm and the supernatant removed. The DNA pellet was re‐dissolved in Solution IV (10 mm Tris‐HCl, 0·1 mm EDTA, 1 m NaCl, pH 8·0) at 0·5–1 ml per gram starting material, followed by ethanol precipitation of the DNA. The pellet was washed with 70 % ethanol, dried and re‐suspended in a minimal volume of TE buffer at 0·1–0·5 ml per gram starting material.

AFLP analysis

AFLP analysis was carried out according to Vos et al. (1995) with minor modifications. Restriction digests of genomic DNA with EcoRI and MseI were carried out at 37 °C for 1 h. Following heat inactivation of the restriction endonucleases, genomic DNA fragments were ligated to EcoRI and MseI adapters overnight at 16 °C to generate template DNA for amplification. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in two consecutive reactions. The template DNA generated was first pre‐amplified using AFLP primers each having one selective nucleotide. The PCR products of the pre‐amplification reaction were then used as template, after five‐fold dilution in sterile water, for selective amplification using two AFLP primers, each containing three selective nucleotides. A total of eight primer combinations was used in this study (Table 2). The final PCR products were run on a 6 % denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 1 × TBE buffer. The EcoRI primers used were not radioactively labelled as in the original protocol. Instead, a modified silver staining method was used (Loh et al., 1999).

Table 2.

Sequences of the primers and adapters used for AFLP analysis

| Name/abbreviation | Enzyme | Type | Sequence (5′‐3′) |

| GYY 101/EA+ | EcoRI | Adapter + | CTCGTAGACTGCGTACC |

| GYY 102/EA– | EcoRI | Adapter – | AATTGGTACGCAGTCTAC |

| GYY 103/MA+ | MseI | Adapter + | GACGATGAGTCCTGAG |

| GYY 104/MA– | MseI | Adapter – | TACTCAGGACTCAT |

| *GYY 105/E‐A | EcoRI | Primer +1 | GACTGCGTACCAATTCA |

| GYY 107/E‐AAC | EcoRI | Primer +3 | GACTGCGTACCAATTCAAC |

| GYY 108/E‐AAG | EcoRI | Primer +3 | GACTGCGTACCAATTCAAG |

| GYY 109/E‐ACA | EcoRI | Primer +3 | GACTGCGTACCAATTCACA |

| GYY 110/E‐ACT | EcoRI | Primer +3 | GACTGCGTACCAATTCACT |

| GYY 111/E‐ACC | EcoRI | Primer +3 | GACTGCGTACCAATTCACC |

| GYY 112/E‐ACG | EcoRI | Primer +3 | GACTGCGTACCAATTCACG |

| GYY 113/E‐AGC | EcoRI | Primer +3 | GACTGCGTACCAATTCAGC |

| GYY 114/E‐AGG | EcoRI | Primer +3 | GACTGCGTACCAATTCAGG |

| *GYY 106/M‐C | MseI | Primer +1 | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAAC |

| GYY 115/M‐CAA | MseI | Primer +3 | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAACAA |

| GYY 116/M‐CAC | MseI | Primer +3 | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAACAC |

| GYY 117/M‐CAG | MseI | Primer +3 | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAACAG |

| GYY 118/M‐CAT | MseI | Primer +3 | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAACAT |

| GYY 119/M‐CTA | MseI | Primer +3 | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAACTA |

| GYY 120/M‐CTC | MseI | Primer +3 | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAACTC |

| GYY 121/M‐CTG | MseI | Primer +3 | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAACTG |

| GYY 122/M‐CTT | MseI | Primer +3 | GATGAGTCCTGAGTAACTT |

* Pre‐selective primers

Data analysis

For the diversity analysis, bands were scored as present (1) or absent (0) to form a raw data matrix. A square symmetric matrix of similarity was then obtained using Jaccard’s Similarity Coefficient [x/(y – z)], where x is the number of fragments in common between two taxa, y is the total number of fragments scored and z is the number of fragments absent in both taxa, from the raw data matrix. Genetic diversity estimates (GDEs) were then calculated as 1 – Jaccard’s Similarity Coefficient and used for cluster analysis using the UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean) technique of the NEIGHBOR program in PHYLIP version 3·5c (Felsenstein, 1993). The dendrogram was drawn using TREEVIEW version 1·6·1 (Page, 1996).

RESULTS

AFLP profiles

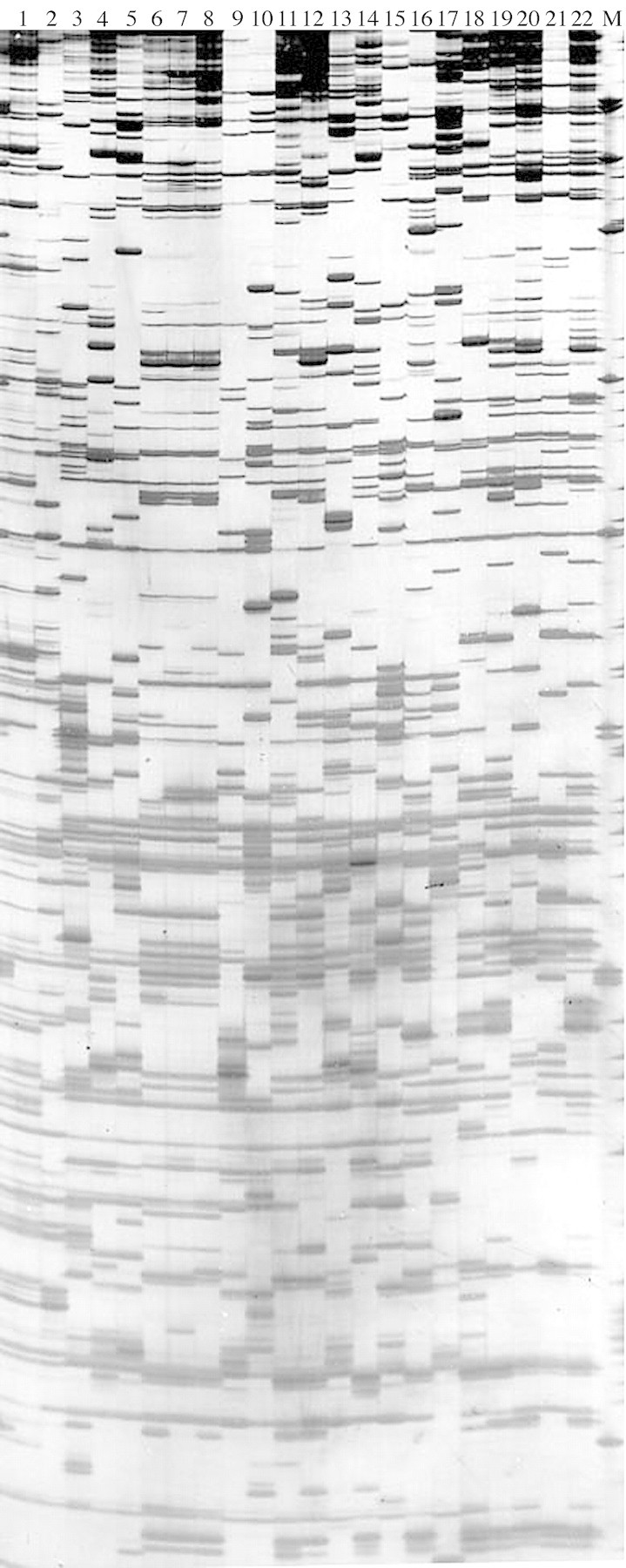

Figure 1 illustrates an AFLP profile generated using primer combination 1 (E‐AAC, M‐CAA). The eight primer combinations used in this study (Table 2) generated an average of 70 bands per primer pair. Only unambiguous bands were scored for analysis, giving a total of 276 unambiguous bands (35 bands per primer pair) of the size 50–500 bp. Of these, 275 bands (99 %) were polymorphic across the whole range of samples.

Fig. 1. AFLP profile generated by primer combination 1 (E‐AAC, M‐CAA). Lane 1, Ensete superbum; lane 2, E. glaucum; lane 3, Musa itinerans; lane 4, M. laterita; lane 5, M. sikkimensis; lanes 6–8, M. gracilis; lane 9, M. acuminata ssp. malaccensis; lane 10, M. balbisiana; lane 11, M. textilis; lane 12, M. violascens; lane 13, M. ornata; lane 14, M. coccinea; lane 15, M. nagensium; lane 16, M. campestris; lane 17, M. velutina; lane 18, M. jackeyi; lane 19, M. beccarii; lane 20, M. suratii; lane 21, M. monticola; lane 22, M. borneensis; lane M, pUC19/HpaII molecular weight marker.

Eleven unique bands were observed for all the taxa examined (Table 3). Musa and Ensete were distinctly separated by the presence of two unique bands in each genus. M. suratii, M. jackeyi Hill and M. itinerans Cheesman were each characterized by two unique bands, and M. sikkimensis Kurz by one unique band, indicating that these species were distinct.

Table 3.

Taxonomic‐specific genetic markers observed

| Primer pair | EcoRI | MseI | Ensete | Musa | M. suratii | M. jackeyi | M. itinerans | M. sikkimensis | Total number of unique markers per primer pair |

| 1 | AAC* | CAA** | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | 2 |

| 2 | AAG | CAC | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | ACA | CAG | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 |

| 4 | ACC | CAT | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 |

| 5 | ACG | CTA | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| 6 | ACT | CTC | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | – | 2 |

| 7 | AGC | CTG | 1 | – | 1 | 2 | 1 | – | 5 |

| 8 | AGG | CTT | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 11 |

EcoRI*, EcoRI‐adapter based primer; the selective nucleotides added at the 3′ end are indicated.

MseI**, MseI‐adapter based primer; the selective nucleotides added at the 3′ end are indicated.

Genetic similarities

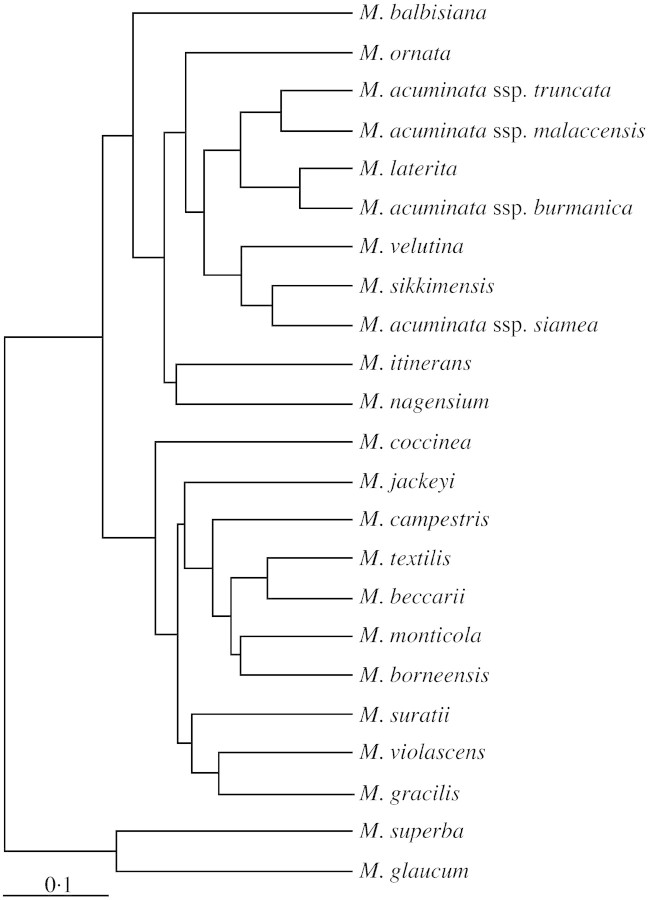

Phenetic analysis based on genetic diversity estimates (GDEs) (Table 4) showed that the genus Musa was clearly separated from the genus Ensete, supporting their positions as distinct genera (Fig. 2). Within the genus Musa, species segregated into two main groups corresponding to the chromosome number: n = x = 10 in sect. Callimusa and sect. Australimusa; and n = x = 11 in sect. Musa and sect. Rhodochlamys. These molecular data supported the separation of Musa species into sections with chromosomes n = x = 10 and n = x = 11.

Table 4.

GDEs of eight primer combinations

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | |

| 1 | 0·224 | 0·509 | 0·530 | 0·649 | 0·435 | 0·426 | 0·713 | 0·310 | 0·346 | 0·740 | 0·318 | 0·474 | 0·515 | 0·448 | 0·561 | 0·565 | 0·428 | 0·556 | 0·524 | 0·581 | 0·581 | 0·549 |

| 2 | 0·487 | 0·512 | 0·644 | 0·351 | 0·424 | 0·704 | 0·242 | 0·278 | 0·731 | 0·251 | 0·452 | 0·478 | 0·396 | 0·553 | 0·512 | 0·338 | 0·506 | 0·530 | 0·540 | 0·588 | 0·525 | |

| 3 | 0·546 | 0·565 | 0·494 | 0·503 | 0·751 | 0·469 | 0·490 | 0·749 | 0·534 | 0·490 | 0·563 | 0·482 | 0·540 | 0·521 | 0·455 | 0·544 | 0·545 | 0·599 | 0·588 | 0·547 | ||

| 4 | 0·353 | 0·546 | 0·640 | 0·764 | 0·479 | 0·507 | 0·772 | 0·543 | 0·474 | 0·670 | 0·556 | 0·378 | 0·361 | 0·544 | 0·266 | 0·249 | 0·358 | 0·357 | 0·341 | |||

| 5 | 0·656 | 0·716 | 0·745 | 0·565 | 0·622 | 0·824 | 0·627 | 0·540 | 0·722 | 0·572 | 0·466 | 0·503 | 0·614 | 0·434 | 0·446 | 0·429 | 0·453 | 0·342 | ||||

| 6 | 0·413 | 0·688 | 0·397 | 0·377 | 0·725 | 0·401 | 0·495 | 0·468 | 0·445 | 0·532 | 0·468 | 0·422 | 0·549 | 0·594 | 0·581 | 0·594 | 0·558 | |||||

| 7 | 0·718 | 0·379 | 0·435 | 0·772 | 0·439 | 0·589 | 0·419 | 0·474 | 0·599 | 0·547 | 0·407 | 0·656 | 0·604 | 0·637 | 0·646 | 0·617 | ||||||

| 8 | 0·716 | 0·767 | 0·533 | 0·733 | 0·716 | 0·708 | 0·725 | 0·749 | 0·762 | 0·687 | 0·804 | 0·748 | 0·736 | 0·684 | 0·721 | |||||||

| 9 | 0·315 | 0·729 | 0·260 | 0·439 | 0·411 | 0·240 | 0·485 | 0·459 | 0·268 | 0·514 | 0·484 | 0·488 | 0·489 | 0·463 | ||||||||

| 10 | 0·742 | 0·186 | 0·474 | 0·457 | 0·452 | 0·525 | 0·561 | 0·423 | 0·522 | 0·542 | 0·545 | 0·560 | 0·512 | |||||||||

| 11 | 0·726 | 0·725 | 0·792 | 0·741 | 0·795 | 0·798 | 0·724 | 0·792 | 0·787 | 0·788 | 0·728 | 0·768 | ||||||||||

| 12 | 0·493 | 0·439 | 0·411 | 0·588 | 0·570 | 0·398 | 0·584 | 0·550 | 0·554 | 0·561 | 0·544 | |||||||||||

| 13 | 0·607 | 0·518 | 0·364 | 0·468 | 0·463 | 0·458 | 0·434 | 0·440 | 0·477 | 0·497 | ||||||||||||

| 14 | 0·472 | 0·695 | 0·629 | 0·466 | 0·664 | 0·689 | 0·677 | 0·641 | 0·661 | |||||||||||||

| 15 | 0·564 | 0·514 | 0·328 | 0·601 | 0·590 | 0·585 | 0·547 | 0·585 | ||||||||||||||

| 16 | 0·375 | 0·516 | 0·308 | 0·344 | 0·419 | 0·361 | 0·411 | |||||||||||||||

| 17 | 0·417 | 0·300 | 0·282 | 0·448 | 0·449 | 0·431 | ||||||||||||||||

| 18 | 0·539 | 0·494 | 0·505 | 0·558 | 0·545 | |||||||||||||||||

| 19 | 0·343 | 0·425 | 0·480 | 0·377 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 0·417 | 0·391 | 0·325 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | 0·405 | 0·353 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | 0·411 |

Taxa 1–23 correspond to the list of species in Table 1

Fig. 2. Dendrogram showing genetic similarities between species of Musa and Ensete using UPGMA cluster analysis. Scale bar depicts GDEs.

Within the Rhodochlamys and Musa clusters, M. balbisiana Colla formed a distinct branch, while the remaining species in the cluster were separated into two groups. The first cluster included M. ornata Roxb., the four subspecies of M. acuminata Colla, M. laterita Cheesman, M. velutina H. Wendl & Drude and M. sikkimensis, while the second cluster included M. itinerans and M. nagensium Prain. Species from sect. Rhodochlamys, M. ornata, M. laterita and M. velutina were embedded within sect. Musa, suggesting that the separation of sect. Rhodochlamys from sect. Musa was not clear‐cut.

Within the Callimusa and Australimusa clusters, M. coccinea Andr. was distantly placed from the other species. The cluster divided into two subclusters. One subcluster included M. jackeyi, M. campestris Becc., M. textilis Née, M. beccarii, M. monticola and M. borneensis Becc.; while M. suratii, M. gracilis Holttum and M. violascens Ridl. formed the second subcluster, with M. gracilis clustering closer to M. violascens than to M. suratii. Species from sect. Australimusa, M. beccarii, M. monticola, M. textilis and M. jackeyi were nestled within species of sect. Callimusa, indicating a blurring of the distinction between sect. Callimusa and sect. Australimusa.

DISCUSSION

AFLP has provided important information regarding the genetic relationships among taxa of sections of Musa. In addition, it has generated unique molecular markers for the identification of Musa species. The level of polymorphism in Musa and the number of loci generated per primer pair using AFLP compare favourably with other techniques. A study employing ISSRs in Musa (Godwin et al., 1997) generated 940 bands from ten primer pairs, but only 13·1 % were polymorphic, while RFLP analysis of Musa (Gawel et al., 1992) using 66 primers generated only 96 alleles, an average of two alleles per probe.

The distinct separation of the clusters comprising species with chromosome numbers n = x = 11 in sect. Musa and Rhodochlamys, and species with chromosome numbers n = x = 10 in sect. Callimusa and Australimusa, is in agreement with previous taxonomic alignment based on morphological data. Cheesman (1947) noted that chromosomal differences between taxa of sect. Callimusa–Australimusa and sect. Musa–Rhodochlamys were correlated with many small differences in their habits and physiology, and regarded chromosome number as the best and safest criterion of relationships within Musa. This study is in agreement with Cheesman’s data and also the cytogenetic evidence of Simmonds (1962) and Shepherd (1990) and the more recent study on species in sections Musa and Rhodochlamys using RFLP by Jarret and Gawel (1995).

Relationships between sect. Musa and Rhodochlamys

Based on phenetic analyses, no clear distinction was apparent between species of sect. Rhodochlamys and those of sect. Musa. M. velutina (sect. Rhodochlamys) was embedded within species of sect. Musa, and M. laterita (sect. Rhodochlamys) nestled within subspecies of M. acuminata. Musa ornata (sect. Rhodochlamys) also fell within the generally larger cluster of sect. Musa. These results suggested that sect. Rhodochlamys and sect. Musa are not sufficiently distinct genetically to warrant separation into two sections. This is in agreement with the conclusions of Simmonds (1962), Shepherd (1990) and Jarret and Gawel (1995).

Musa balbisiana was shown to be most distant in the present analysis. It is generally considered a distinct species (Cheesman, 1948; Simmonds, 1962) and other molecular studies have demonstrated its position as a species isolated within sect. Musa (Simmonds and Weatherup, 1990; Gawel and Jarret, 1991; Gawel et al., 1992; Jarret et al., 1992).

Genetic diversity estimates clearly showed that the three species of sect. Rhodochlamys, M. ornata, M. laterita and M. velutina, were genetically most closely related to M. acuminata in sect. Musa. Among the species in sect. Rhodochlamys, M. laterita clustered closely with M. acuminata. This is in agreement with the observation of Simmonds (1962) that M. laterita was closely related to M. acuminata, forming the nearest relationship between sections Rhodochlamys and Musa.

Hybridization is known to be common between species from sect. Musa and sect. Rhodochlamys, producing relatively vigorous offspring. According to Simmonds (1962), M. acuminata (sect. Musa) crosses effectively with M. laterita, M. ornata and M. velutina (all from sect. Rhodochlamys), while M. balbisiana (sect. Musa) hybridizes successfully with almost all species, including M. laterita and M. velutina. The weak reproductive barrier between the two sections supports the notion that they are not distinct.

Musa acuminata ssp. siamea did not cluster with the other subspecies of M. acuminata but clustered instead with M. sikkimensis. Lanaud et al. (1992) noted that ssp. siamea represented a highly diversified group. AFLP analysis suggests that it could be regarded as a separate species distinct from M. acuminata.

Cheesman (1947) noted that sect. Musa and sect. Rhodochlamys, although regarded as a close assemblage, were initially separated for convenience, sect. Musa including the edible bananas with dull bracts while sect. Rhodochlamys included the ornamental bananas with brightly coloured bracts. This view is no longer tenable in the face of genetic evidence and these two sections should be merged into a single section, sect. Musa.

Relationships between sect. Callimusa and sect. Australimusa

These two sections were separated on the basis of conspicuous differences between their seeds (Cheesman, 1947). However, AFLP revealed no genetic justification for this separation, showing species of sect. Australimusa, M. jackeyi, M. textilis, M. beccarii and M. monticola (Wong et al., 2001a) clustering among species of sect. Callimusa.

Results obtained revealed that M. textilis (sect. Australimusa) clustered most closely with M. beccarii (sect. Australimusa; Wong et al., 2001a), with a GDE value of 0·249. However, M. textilis and M. borneensis of sect. Callimusa were also closely related, with a GDE value of 0·266, compared with genetic similarity between M. textilis and M. jackeyi in sect. Australimusa with a GDE of 0·357. Similarly, M. jackeyi was closely related to M. campestris of sect. Callimusa with a GDE value of 0·361, thus showing that species from sect. Australimusa were closely related to species from sect. Callimusa, and that the two sections were not distinct. Indeed, M. suratii, a new species described by Argent (2000), is not only intermediate between these two sections (Wong et al., 2001a) but has unique seed morphology that does not conform with that of either sect. Callimusa or sect. Australimusa.

Likewise, M. coccinea of sect. Callimusa, the species most distant from the other Callimusa species, was found to be genetically closely related to M. textilis and M. jackeyi of sect. Australimusa with GDEs of 0·474 and 0·477, respectively. This contrasted with the more distant relationship between M. coccinea and M. violascens (sect. Callimusa), with a GDE value of 0·540. This showed that species from two different sections were genetically more similar to one another than were two species from the same section (M. coccinea and M. violascens).

The distinction between sections Callimusa and Australimusa is based on a single character, that of seed structure. As mentioned above, M. suratii has unique seeds that do not conform to those of either sect. Callimusa or sect. Australimusa, thus breaking down the distinction between the two sections. In addition, hybridization is known to occur in the wild between species of both sections; for example, in Sabah, Borneo, hybridization occurs between M. borneensis in sect. Callimusa and M. textilis in sect. Australimusa (Kiew, 1998), showing that the sections are indeed not genetically distinct. The results of this AFLP analysis and those of Wong et al. (2001a) show that sections Callimusa and Australimusa are not genetically distinct and should be merged into a single section.

CONCLUSIONS

Results of AFLP analysis showed that the 11‐chromosome and 10‐chromosome grouping are robust and justified and that the separation of Musa species into different groups based on their chromosome numbers provides a reliable means for classifying Musa species into sections. In contrast, the separations of sect. Rhodochlamys from sect. Musa, and sect. Australimusa from sect. Callimusa were not supported by the AFLP analysis. Indeed, there is more genetic variation within the two groupings, sect. Musa–Rhodochlamys and Callimusa–Australimusa, than there is between sect. Musa and sect. Rhodochlamys and between sect. Callimusa and sect. Australimusa, drawing attention to the fact that striking differences in morphological characters in Musa species are not always indicative of the same degree of genetic difference.

Results from the AFLP analysis provide evidence that sect. Rhodochlamys should be combined with sect. Musa, a view already mooted by Simmonds (1962), Shepherd (1990), and Jarret and Gawel (1995), and that sect. Callimusa and sect. Australimusa should also be combined into a single section.

In view of the importance of chromosome numbers in grouping species within the genus Musa, it will be of great interest to carry out a molecular study on the sole member of sect. Ingentimusa that has a chromosome number of n = x = 14.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by the Academic Research Fund, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, RP 12/98/GYY. We thank the Directors of the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, and the Singapore Botanic Gardens for permission to collect leaf samples, and Anthony Lamb (Agricultural Park, Tenom, Malaysia) for providing plant materials.

Supplementary Material

Received: 15 November 2001; Returned for revision: 7 January 2002; Accepted: 22 April 2002

References

- AggarwalRK, Brar DS, Nandi S, Huang N, Khush GS.1999. Phylogenetic relationships among Oryza species revealed by AFLP markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 98: 1320–1328. [Google Scholar]

- ArgentGCG.1976. The wild bananas of Papua New Guinea. Notes from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh 35: 77–114. [Google Scholar]

- ArgentGCG.2000. Two interesting wild Musa species (Musaceae) from Sabah, Malaysia. Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 52: 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- BakerJG.1893. A synopsis of the genera and species of Museae. Annals of Botany 7: 189–229. [Google Scholar]

- BhatKV, Bhat SR, Chandel KPS.1992. Survey of isozyme polymorphism for clonal identification in Musa II. Peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, shikimate dehydrogenase and malate dehydrogenase. Journal of Horticultural Science 67: 737–743. [Google Scholar]

- CheesmanEE.1947. Classification of the bananas. II. The Genus Musa L. Kew Bulletin 2: 106–117. [Google Scholar]

- CheesmanEE.1948. Classification of the bananas. III. Critical notes on species. a. M. balbisiana Kew Bulletin 3: 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- CrouchJH, Crouch HK, Constandt H, Van Gysel A, Breyne P, Van Montagu M, Jarret RL, Ortiz R.1999. Comparison of PCR‐based molecular marker analyses of Musa breeding populations. Molecular Breeding 5: 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- FelsensteinJ.1993. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package) version 3·5c. Department of Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle (distributed by the author). [Google Scholar]

- GawelNJ, Jarret RL.1991. Chloroplast DNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) in Musa species. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 81: 783–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GawelNJ, Jarret RL, Whittemore AP.1992. Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)‐based phylogenetic analysis of Musa Theoretical and Applied Genetics 84: 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GodwinID, Aitken EAB, Smith LW.1997. Application of inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers to plant genetics. Electrophoresis 18: 1524–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GrapinA, Noyer JL, Carreel F, Dambler D, Baurens FC, Lanaud C, Lagoda PJL.1998. Diploid Musa acuminata genetic diversity assayed with sequence tagged microsatellite sites. Electrophoresis 19: 1374–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HillM, Witsenboer H, Zabeau M, Vos P, Kesseli R, Michelmore R.1996. PCR‐based fingerprinting using AFLPs as a tool for studying genetic relationships in Lactuca spp. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 93: 1202–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HowellEC, Newbury HJ, Swennen RL, Withers LA, Ford‐Lloyd BV.1994. The use of RAPD for identifying and classifying Musa germplasm. Genome 37: 328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JarretRL, Gawel NJ.1995. Molecular markers, genetic diversity and systematics. In: Gowen S, ed. Bananas and plantains London: Chapman and Hall, 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- JarretRL, Gawel N, Whittemore A, Sharrock S.1992. RFLP‐based phylogeny of Musa species in Papua New Guinea. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 84: 579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KiewR.1998. Wanderings in the great forests of Borneo. Gardenwise 11: 8–9, 11. [Google Scholar]

- LanaudC, Tezenas du Montcel H, Jolivot MP, Glaszmann JC, Gonzalez De Leon D.1992. Variation of ribosomal gene spacer length among wild and cultivated banana. Heredity 68: 147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LiHW.1978. The Musaceae of Yunnan. Acta Phytotaxomomica Sinica 16: 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- LohJP, Kiew R, Kee A, Gan LH, Gan YY.1999. Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) provides molecular markers for the identification of Caladium bicolor cultivars. Annals of Botany 84: 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- LohJP, Kiew R, Ohn S, Gan LH, Gan YY.2000a A study of genetic variation and relationships within the Bamboo subtribe Bambusinae using amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP). Annals of Botany 85: 607–612. [Google Scholar]

- LohJP, Kiew R, Set O, Gan LH, Gan YY.2000b Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) fingerprinting of 16 banana cultivars (Musa spp.). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 17: 360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LohJP, Kiew R, Hay A, Kee A, Gan LH, Gan YY.2000c Intergeneric and interspecific relationships in Araceae tribe Caladiae and development of molecular markers using amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP). Annals of Botany 85: 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- OsujiJO, Crouch J, Harrison G, Heslop‐Harrison JS.1998. Molecular cytogenetics of Musa species, cultivars and hybrids: location of 18S‐5·8S‐25S and 5S rDNA and telomere‐like sequences. Annals of Botany 82: 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- OsujiJO, Harrison G, Crouch J, Heslop‐Harrison JS.1997. Identification of the genomic constitution of Musa L. lines (bananas, plantains and hybrids) using molecular cytogenetics. Annals of Botany 80: 787–793. [Google Scholar]

- PageRDM.1996. TREEVIEW: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Computer Applications in the Biosciences 12: 357–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PowellW, Morgante M, Andre C, Hanafey M, Vogel J, Tingey S, Rafalski A.1996. The comparison of RFLP, RAPD, AFLP and SSR (microsatellite) markers for germplasm analysis. Molecular Breeding 2: 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- ReichardtMJ, Rogers SJ.1993. Plant DNA isolation using CTAB. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, eds. Current protocols in molecular biology. USA: John Wiley and Sons, Supplement 22. [Google Scholar]

- SagotP.1887. Sur le Genre Bananier. Bulletin de la Societe Botanique de France 34: 328–330. [Google Scholar]

- ShepherdK.1959. Two new basic chromosome numbers in Musaceae. Nature 183: 1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ShepherdK.1990. Observations on Musa taxonomy. In: Jarret RL, ed. Identification of genetic diversity in the genus Musa: Proceedings of an international workshop held at Los Banos, Philippines, 5–10 September 1988. France: INIBAP, Montferrier‐sur‐Lez, 158–165. [Google Scholar]

- SimmondsNW.1960. Notes on banana taxonomy. Kew Bulletin 14: 198–212. [Google Scholar]

- SimmondsNW.1962. The evolution of the bananas. London: Longmans. [Google Scholar]

- SimmondsNW, Weatherup STC.1990. Numerical taxonomy of the wild bananas (Musa). New Phytologist115: 567–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VosP, Hogers R, Bleeker M, Reijans M, van de Lee T, Hornes M, Frijters A, Pot J, Peleman J, Kupier M, Zabeau M.1995. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Research 23: 4407–4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WongC, Kiew R, Ohn S, Lamb A, Lee SK, Gan LH, Gan YY.2001a Sectional placement of three Bornean species of Musa (Musaceae) based on AFLP. Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 53: 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- WongC, Kiew R, Loh JP, Gan LH, Lee SK, Ohn S, Lum S, Gan YY.2001b Genetic diversity of the wild banana Musa acuminata Colla in Malaysia as evidenced by AFLP. Annals of Botany 88: 1017–1025. [Google Scholar]

- ZhangWP, Wendel JF, Clark LG.1997. Bamboozled again! Inadvertent isolation of fungal rDNA sequences from bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 8: 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.