Abstract

The effects of season and cold storage on morphogenic competence in mature Pinus sylvestris buds were investigated. Peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase activity were measured as markers of oxidative metabolism. No growth in vitro was observed on explants detached from the end of January until the beginning of March. Brachioblasts, each with a couple of needles, formed on 11 % of the buds without macrostrobili that were detached in early April and introduced immediately into culture. Of the explants detached in late July, 15 % formed shoots with brachioblasts and needles. The lowest activity of peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase in pine buds was observed from the end of April until the beginning of June when morphogenic competence of tissues started to increase. Development of bud explants detached in January was achieved by cold storage for 5 months. Low polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase activity coincided with increased morphogenic potential. Results suggest that reduced or stable activity of peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase is associated with an increased ability of tissues to start growth in vitro.

Key words: Pinus sylvestris L., Scots pine, buds, morphogenic competence, peroxidase, polyphenol oxidase, seasonal changes, cold storage

INTRODUCTION

Micropropagation of mature trees is important because it allows multiplication of superior genotypes identified in the field. Successful in vitro regeneration of conifers has been achieved using embryos or young seedlings (Bonga, 1991). However, maturation appears to be a problem that prevents wider application of tissue culture technology among woody species (Pierik, 1990). Also, stress due to hormonal and other stimuli in the nutrient media can cause accelerated maturation (Bonga, 1987).

Successful micropropagation of mature Pinus is reported for few species, including Pinus radiata (Horgan and Holland, 1989), P. pinaster (Monteuuis and Dumas, 1992), P. brutia (Abdullah et al., 1987), P. lambertiana (Gupta and Durzan, 1985), P. taeda (Mott and Amerson, 1981) and P. nigra (Jelaska et al., 1981). Of the Pinus species, Scots pine (P. sylvestris L.) is especially difficult to deal with in culture (Hohtola, 1988). Successful micropropagation of Scots pine has been established only via organogenesis from young seedlings (Jain et al., 1988; Supriyanto and Rohr, 1994; Häggman et al., 1996; Sul and Korban, 1998; Andersone and Ievinsh, 2000). In the case of shoot tip cultures from mature Scots pines, tissue browning and slow deterioration of the cellular ultrastructure, which finally leads to necrosis, makes tissue culture work difficult (Lindfors et al., 1990).

Oxidative enzymes, e.g. peroxidases and polyphenol oxidases, participate in browning of in vitro cultures (Dowd and Norton, 1995). In callus cultures derived from shoot tips of mature Scots pine, browning was a consequence of high oxidative stress (Laukkanen et al., 2000). It is possible that after introduction into in vitro culture, plant tissues with a reduced capacity for oxidative reactions will show less browning and, as a consequence, better morphogenic competence. As pronounced seasonal changes in cellular metabolism have been described for Scots pine buds (Hohtola, 1988), it is possible that the capacity for oxidative reactions changes during the growth season. On the other hand, prolonged cold storage could be used as a tool for affecting oxidative metabolism. It has been shown that cold storage of Scots pine roots for 4 months significantly decreases peroxidase activity (Ahonen et al., 1989).

The aim of the present work was to investigate changes of morphogenic competence in mature P. sylvestris buds due to seasonal effects or cold storage. Peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase activities were measured as markers of oxidative metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Experiments were performed from the end of January (average temperature –5·5 °C) until the end of July (average temperature +17 °C). Buds were collected twice a month from mature pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) trees in a seed orchard near Riga, Latvia. Plant material was taken randomly from different trees from the lower part of the crown. The upper part of resting vegetative buds, tips of the new shoots or newly formed buds (according to the growth phase) were used. Each time, six replicates of 20 buds per replicate were used as explants and three replicates were used for enzymatic analysis.

To investigate the effect of cold storage on morphogenesis, resting buds were collected in winter (January) and spring (April). Buds were surface sterilized and placed in closed containers at 5 °C. Twice a month, three replicates of 20 cold‐stored buds per replicate were used as explants and three replicates were used for enzymatic analysis.

For surface disinfection, buds were washed in a solution of household soap for 1 h and then rinsed in tapwater for 1 h. They were surface sterilized with a half‐diluted commercial bleach ACE (Procter & Gamble, Riga, Latvia; containing 5–15 % sodium hypochlorite) for 20 min, rinsed for 10 min in sterile distilled water, sterilized again in 15 % hydrogen peroxide and rinsed three times for 10 min in sterile distilled water. The buds were peeled and dissected aseptically.

Cold‐stored buds were sterilized twice, once before cold storage when they were washed, sterilized with bleach and rinsed with distilled water, and again after cold storage when they were sterilized with bleach, rinsed, sterilized with hydrogen peroxide and rinsed again.

Culture conditions and media

Explants were cultivated in 20 × 200 mm glass test‐tubes containing 10 ml agarized nutrient medium. Tubes were closed with cotton wool plugs. Cultures consisted of one explant per tube. They were cultivated at 23 ± 3 °C with a 16 h photoperiod. Illumination was provided by fluorescent tubes (LB80–1 and LB80–7) combined with sunlight.

Explants were placed on medium no. 1 or medium no. 2 with Woody Plant Medium mineral salts (Lloyd and McCown, 1981), vitamins, and other components and hormones (Table 1). Medium no. 1 was used for microshoot formation on cold‐stored explants as well as for callus induction. Medium no. 2 was used for induction of needle formation.

Table 1.

Media used for cultivation of Pinus sylvestris explants

| Medium no. 1 | Medium no. 2 | |

| Woody Plant Medium mineral salts | + | + |

| AgNO3 20 mg l–1 | +/– | +/– |

| Myo‐inositol | 100 mg l–1 | 100 mg l–1 |

| Thiamine hydrochloride | 30 mg l–1 | 30 mg l–1 |

| Pyridoxine hydrochloride | 10 mg l–1 | 10 mg l–1 |

| Nicotinic acid | 10 mg l–1 | 10 mg l–1 |

| Dry egg powder | 100 mg l–1 | – |

| Coconut milk | 0·5 % v/v | – |

| Benzyladenine | 5 mg l–1 | – |

| Adenine | – | 10 mg l–1 |

| Kinetine | – | 1 mg l–1 |

| Indole‐3‐acetic acid | 0·2 mg l–1 | – |

| Naftylacetic acid | 0·2 mg l–1 | 0·1 mg l–1 |

| Sucrose | 45 g l–1 | 45 g l–1 |

| Agar | 7 g l–1 | 7 g l–1 |

| pH | 5·8 | 5·8 |

Measurement of peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase activity

For polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase measurement, buds without scales (0·5 g) were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to fine powder with a mortar and pestle. Enzymes were extracted with 25 mmol l–1 HEPES/KOH buffer (pH 7·2) containing 1 mmol l–1 EDTA, 3 % (w/v) PVPP and 0·8 % (v/v) Triton X‐100 for 15 min at 4 °C. The homogenate was centrifuged at 15 000 g for 20 min. The supernatant was used for assays. Protein was determined according to the method of Bradford (1976) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Peroxidase activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 470 nm in reaction mixture containing 2 ml 50 mmol l–1 sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7·0) with 10 mmol l–1 guaicol, 0·5 ml 0·03 mol l–1 H2O2 and 0·01 ml enzymatic extract. The reaction mixture without H2O2 was used as a reference.

The activity of polyphenol oxidase was determined spectrophotometrically in a reaction mixture (3 ml) containing 20 mmol l–1 sodium phosphate (pH 6·5) with 25 mmol l–1 pyrocatechol and the enzymatic extract (0·01 ml). The change in absorbance was monitored at 410 nm.

RESULTS

The effect of developmental phase on morphogenic competence in vitro and enzyme activities

The parts of the buds, used as explants, had macrostrobili (Table 2). No growth response of macrostrobili could be observed in vitro on explants detached from the end of January until the beginning of March. They exhibited browning, without any changes in size and structure. Rapid formation of callus on macrostrobili was observed when buds were introduced into culture between the end of March and the end of April, i.e. just before rapid growth of macrostrobili (Table 2; Fig. 1A). Callus was formed on about 90 % of macrostrobili near the tip of the bud as well as on those isolated from the bud and placed directly on the surface of the medium. The callus was larger in the latter case. Browning of the callus began within 2 weeks and led to necrosis after 1 month.

Table 2.

The effect of developmental phase on morphogenic competence of Pinus sylvestris bud explants in vitro

| Date of introduction into culture | Sterile explants (%)* | Sterile explants with macrostrobili on medium no. 1 (%)† | Sterile explants forming callus on medium no. 1 (%)† | Sterile explants forming brachioblasts with needles on medium no. 2 (%)‡ |

| 29 January | 100 ± 0a | 87 ± 3a | 0 | 0 |

| 18 February | 39 ± 2b | 69 ± 3b | 0 | 0 |

| 4 March | 35 ± 1b | 67 ± 2b | 0 | 0 |

| 23 March | 27 ± 1c | 96 ± 2c | 88 ± 3a | 0 |

| 3 April | 24 ± 1c | 94 ± 2c | 98 ± 2a | 11 ± 2a |

| 15 April | 32 ± 1b | 83 ± 2a | 80 ± 3a | 0 |

| 29 April | 37 ± 3b | 89 ± 3a | 92 ± 4a | 0 |

| 18 May | 40 ± 2b | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 June | 21 ± 2c | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 June | 29 ± 2bc | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 July | 23 ± 1c | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 July | 42 ± 2b | 0 | 0 | 15 ± 2a |

Values within a column with the same superscript are not significantly different at P = 0·05 among dates using Student’s t‐test.

* Sterilization of this material was very difficult. Values (± s.e.) are means of six independent replicates, 20 explants each (three replicates on medium no. 1 and three on medium no. 2).

† Values (± s.e.) are percentage means from sterile explants of three independent replicates.

‡ Values (± s.e.) are percentage means from sterile explants of three independent replicates.

Fig. 1. A, Isolated microstrobilus initial of mature Pinus sylvestris with callus 2 weeks after introduction in vitro. The bud was excised at the end of March. Medium no. 2. B, Mature P. sylvestris explant with brachioblast and a pair of needles 2 months after introduction in vitro. The bud was excised on 3 April. Medium no. 1 for first month; medium no. 2 for second month. C, Mature P. sylvestris explant with shoots consisting of brachioblasts and needles 2 months after introduction in vitro. The bud was excised in late July. Medium no. 2. D, Mature P. sylvestris explant with microshoots 6 weeks after introduction in vitro. The bud was excised in late January and stored at 5 °C for 5 months. Medium no. 1.

On 11 % of the buds detached in early April and introduced immediately into culture, formation of brachioblasts with a couple of needles was observed (Table 2; Fig. 1B). Needles were up to 4 mm long. The rest of the explants did not show any signs of development and turned brown.

In late July, when new buds had already formed on the tips of branches, 15 % of explants detached at that time formed shoots with brachioblasts and needles up to 3 cm in length on medium no. 2 (Table 2; Fig. 1C).

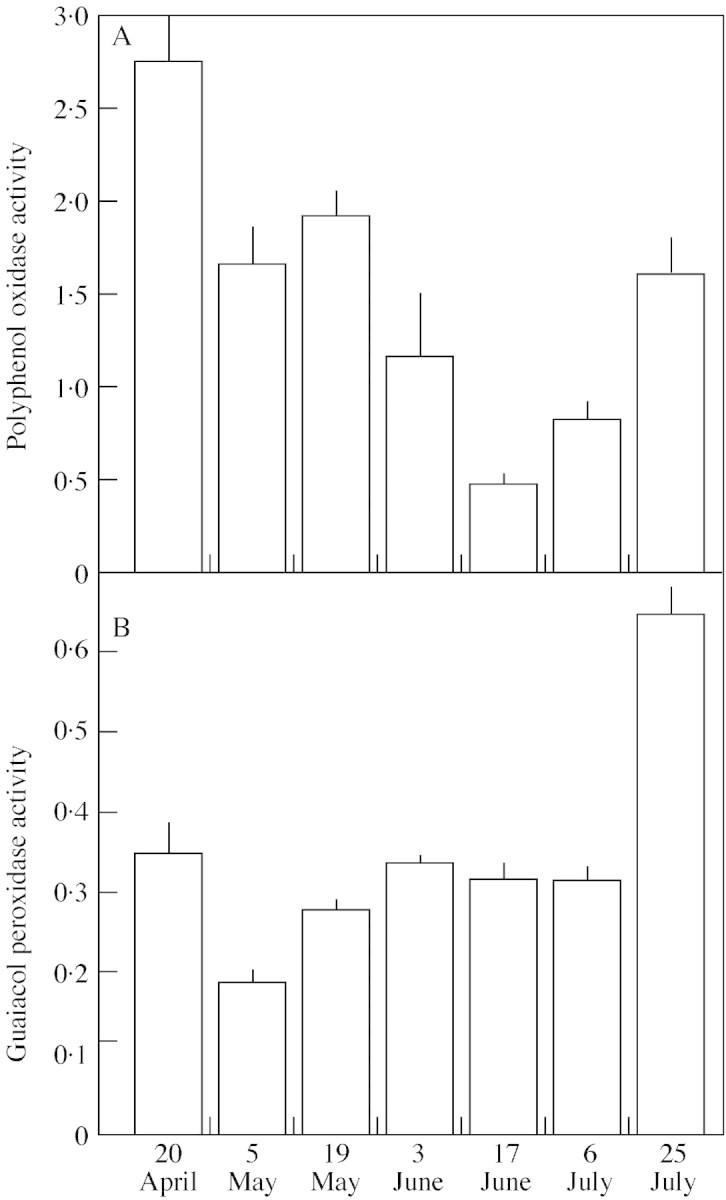

Activity of peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase was monitored in intact pine buds during the growth season. The activity of peroxidase gradually decreased from the end of January until the end of April, and was lowest from the end of April until the beginning of June (Fig. 2A), increasing again from mid‐June. The level of polyphenol oxidase fluctuated more than that of peroxidase during the growth season (Fig. 2B). At the beginning of April, when the buds started to open, the activity of polyphenol oxidase decreased. The period of lowest activity was the same for both enzymes—from the end of April until the beginning of June. During this period the most active new shoot growth occurred. In the middle of June, when maturation of new shoots began, the activity of the enzymes increased, but in July the increase stopped.

Fig. 2. Time course of polyphenol oxidase activity (A) and guaiacol peroxidase activity (B) in intact P. sylvestris buds during the growth season. Enzyme activities are expressed as ΔA min–1 mg–1 protein. Values (± s.e.) are means of three independent measurements for each date.

The effect of cold storage on morphogenesis and enzyme activities

Buds detached in winter and spring did not develop in vitro without any special treatment and gradually browned over the course of a few weeks. Development of such explants was achieved by using cold storage. A considerable increase (about two‐fold) of the apical part of the bud was seen on 15 % of buds detached in January and stored at 5 °C for 2 weeks before being introduced into culture, but they did not form shoots (Table 3). When buds detached in January were stored in the cold for 5 months and then introduced into culture in late June, 30 % of them produced microshoots on medium no. 1 (Table 3; Fig. 1D).

Table 3.

The effect of cold storage on morphogenic competence of Pinus sylvestris bud explants in vitro

| Date of introduction into culture | Sterile explants (%)* | Sterile explants exhibiting bud growth on medium no. 1 (%)† | Sterile explants forming microshoots on medium no. 1 (%)‡ |

| 30 January | 100 ± 0a | 0 | 0 |

| 14 February | 64 ± 2b | 15 ± 1 | 0 |

| 5 March | 54 ± 2c | 0 | 0 |

| 24 March | 53 ± 4bc | 0 | 0 |

| 5 April | 21 ± 2d | 0 | 0 |

| 21 April | 16 ± 2d | 0 | 0 |

| 6 May | 21 ± 5d | 0 | 0 |

| 20 May | 3 ± 2e | 0 | 0 |

| 4 June | 4 ± 1e | 0 | 0 |

| 21 June | 16 ± 2d | 0 | 32 ± 2 |

| 7 July | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 July | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Buds were detached on 30 January.

* Sterilization of this material was very difficult. Values (± s.e.) are means of three independent replicates, 20 explants each.

† Values (± s.e.) are percentage means from sterile explants of three independent replicates.

‡ Values (± s.e.) are percentage means from sterile explants of three independent replicates. Values within a column with the same superscript are not significantly different at P = 0·05 among dates using Student’s t‐test.

During cold storage of mature resting buds the activity of polyphenol oxidase decreased from April to June and increased slightly from June to July (Fig. 3A). The activity of peroxidase in cold‐stored buds fluctuated during the period of investigation (Fig. 3B). The activity was lowest at the beginning of May and at the beginning of July, but increased rapidly towards the end of July.

Fig. 3. Time course of polyphenol oxidase activity (A) and guaiacol peroxidase activity (B) during cold storage (5 °C) of mature resting P. sylvestris buds detached in January. Enzyme activities are expressed as ΔA min–1 mg–1 protein. Values (± s.e.) are means of three independent measurements for each date.

DISCUSSION

By using cold storage as a means of affecting oxidative metabolism, it was possible to achieve direct morphogenesis on mature pine buds. To our knowledge, this is the first successful case of morphogenesis of mature Scots pine tissues apart from callus formation. In previous experiments, the newly formed adventitious shoot primordia have failed to grow beyond the microscopic level (Hohtola, 1988).

Our experiments involving cold storage of buds before introducing them into culture suggest that prolonged cold storage of detached material could be used to affect metabolic processes in Scots pine tissues. The decreased activity of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase during cold storage indicates the possibility of increased morphogenic activity due to a lowered capacity for oxidative metabolism.

Particularly high peroxidase activities in callus tissues initiated from mature trees cause rapid and early browning and possibly lead to cell death (Laukkanen et al., 1999). It is well known that conifer tissues are especially rich in phenolic substances (Nyman, 1985). Obviously, the damage during in vitro manipulation of cultivated plant material causes mixing of the contents of cellular compartments, leading to oxidation of various phenolic compounds by peroxidases and polyphenol oxidases. Comparing the growth activity of mature pine buds in vitro with changes in the activity of peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase during the growth season showed that the period of decreased enzyme activity coincided with rapid formation of callus tissues on macrostrobili explants. At the time when explants were able to form shoots with brachioblasts and needles, the increase in enzyme activity stopped. These results suggest that reduced or stable activity of peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase leads to an increased ability of tissues to start growth in vitro. It should be mentioned that peroxidases are a diverse group of enzymes that participate in many physiological processes. Therefore, not all the changes of peroxidase activity during cold storage or the growth season could be attributed to tissue browning and deterioration.

However, it is possible that factors other than peroxidases and polyphenol oxidase may contribute to loss of morphogenic competence in mature pine tissues. It has been shown that P. sylvestris has especially strong wounding reactions, including increased activity of enzymes involved in oxidative metabolism that in turn inhibit differentiation and growth (Hohtola, 1988). On the other hand, a relatively high percentage of infections during storage at 4 °C (Table 3) supported the idea that endophytic microbes in Scots pine buds are a potential cause of the defence reactions (Pirttilä et al., 2002). In addition, P. sylvestris may have some specific requirements in the culture medium or growing conditions that have not yet been identified. Further research is therefore needed to optimize conditions for successful multiplication of established cultures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by a grant from the Science Council of Latvia (01·0343).

Supplementary Material

Received: 7 January 2002; Returned for revision: 26 April 2002; Accepted: 9 May 2002

References

- AbdullahAA, Yeoman MM, Grace J.1987. Micropropagation of mature Calabrian pine (Pinus brutia Ten.) from fascicular buds. Tree Physiology 3: 123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AhonenU, Markkola AM, Ohtonen R, Tarvainen O, Väre H.1989. Determination of peroxidase activity in some fungi and in mycorrhizal and non‐mycorrhizal Pinus sylvestris roots. Aquilo Ser Botanica 26: 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- AndersoneU, Ievinsh G.2000. Effect of hormonal and nutritional factors on morphogenesis of Pinus sylvestris L. in vitro Proceedings of the Latvian Academy of Sciences, Section B 54: 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- BongaJM.1987. Clonal propagation of mature trees: problems and possible solutions. In: Bonga JM, Durzan DJ, eds. Cell and tissue culture in forestry, vol. 1 The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff/Dr W Junk Publishers, 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- BongaJM.1991. In vitro propagation of conifers: fidelity of the clonal offspring. In: Ahuja MR, ed. Woody plant biotechnology New York: Plenum Press, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- BradfordMM.1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein‐dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry 72: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DowdPW, Norton RA.1995. Browning‐associated mechanism of resistance to insects in corn callus tissues. Journal of Chemical Ecology 21: 583–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GuptaPK, Durzan DJ.1985. Shoot multiplication from mature trees of Douglas‐fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana). Plant Cell Reports 4: 643–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HäggmanH, Aronen TS, Stomp A‐M.1996. Early‐flowering Scots pines through tissue culture for accelerated tree breeding. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 93: 840–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HohtolaA.1988. Seasonal changes in explant viability and contamination of tissue cultures from mature Scots pine. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 15: 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- HorganK, Holland L.1989. Rooting of micropropagated shoots from mature radiata pine. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 19: 1309–1315. [Google Scholar]

- JainSM, Newton RJ, Soltes EJ.1988. Induction of adventitious buds and plantlet regeneration in Pinus sylvestris L. Current Science 57: 677–679. [Google Scholar]

- JelaskaS, Kolevska‐Pletikapic B, Vidakovic M.1981. Bud regeneration in Pinus nigra embryo and seedling tissue culture. In Colloque International sur la culture in vitro des essences forestieres. Nangis, France: Association Foret Cellulose, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- LaukkanenH, Häggman H, Kontunen‐Soppela S, Hohtola A.1999. Tissue browning of in vitro cultures of Scots pine: role of peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase. Physiologia Plantarum 106: 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- LaukkanenH, Rautiainen L, Taulavuori E, Hohtola A.2000. Changes of cellular structures and enzymatic activities during browning of Scots pine callus derived from mature buds. Tree Physiology 20: 467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LindforsA, Kuusela H, Hohtola A, Kupila‐Ahvenniemi S.1990. Molecular correlates of tissue browning and deterioration in Scots pine calli. Biologia Plantarum 32: 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- LloydG, McCown B.1981. Commercially‐feasible micropropagation of Mountain laurel, Kalmia latifolia, by use of shoot tip culture. International Plant Propagation Society Proceedings 30: 421–427. [Google Scholar]

- MonteuuisO, Dumas E.1992. Morphological features as indicators of maturity in acclimatized Pinus pinaster from different in vitro origins. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 22: 1417–1421. [Google Scholar]

- MottRL, Amerson HV.1981. A tissue culture process for clonal production of loblolly pine plantlets. NC Agricultural Research Series Technical Bulletin 271: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- NymanBF.1985. Protein‐proanthocyanidin interactions during extraction of Scots pine needles. Phytochemistry 24: 2939–3944. [Google Scholar]

- PierikRLM.1990. Rejuvenation and micropropagation. International Association of Plant Tissue Culture Newsletter 62: 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- PirttiläAM, Laukkanen H, Hohtola A.2002. Chitinase production in pine callus (Pinus sylvestris L.) a defense reaction against endophytes? Planta 214: 848–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SulI‐W, Korban SS.1998. Effects of media, carbon sources and cytokinins on shoot organogenesis in the Christmas tree Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). Journal of Horticultural Science & Bio technology 73: 822–827. [Google Scholar]

- Supriyanto, Rohr R.1994. In vitro regeneration of plantlets of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) with mycorrhizal roots from subcultured callus initiated from needle adventitious buds. Canadian Journal of Botany 72: 1144–1150. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.