Abstract

Much has been written about the relationship between a person’s high medical expenses and his or her likelihood of filing for bankruptcy, but the relationship between receiving a cancer diagnosis and filing for bankruptcy is less well understood. We estimated the incidence and relative risk of bankruptcy for people age twenty-one or older diagnosed with cancer compared to people the same age without cancer by conducting a retrospective cohort analysis that used a variety of medical, personal, legal, and bankruptcy sources covering the Western District of Washington State in US Bankruptcy Court for the period 1995–2009. We found that cancer patients were 2.65 times more likely to go bankrupt than people without cancer. Younger cancer patients had 2–5 times higher rates of bankruptcy compared to cancer patients age sixty-five or older, indicating that Medicare insurance and Social Security may mitigate bankruptcy risk for the older group. The findings suggest that employers and governments may have a policy role to play in creating programs and incentives that could help people cover expenses in the first year following a cancer diagnosis.

The financial burden of cancer can be substantial for patients and their families. Data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey suggest that each year $1.3 billion (6.5 percent) of the $20.1 billion spent on cancer care in the nonelderly population comes directly from the patients themselves.1 Deductibles and copayments for cancer treatments, supportive care, and related services, along with nonmedical costs such as child care and lost income, may be financially devastating, even for cancer patients with medical insurance.2

The financial burden of cancer may be particularly severe for patients who are unable to work during treatment.3,4 Between 40 percent and 85 percent of cancer patients stop working during initial treatment, with absences ranging from forty-five days to nearly six months.4,5 Many survivors also face long-term health barriers to working for years after treatment.4 A comparison of earnings of breast cancer patients and age- and work-matched healthy controls found that the patients’ average annual individual earnings fell $3,600 in the five years following diagnosis, while average annual individual earnings for a noncancer comparison group increased $1,800.6 Additionally, a cancer diagnosis can affect all wage earners in a household.

Many people look to bankruptcy laws for protection when debt repayments overwhelm their net income. The extent to which cancer and other serious illnesses contribute to personal bankruptcy filings remains controversial. An important weakness in the illness and bankruptcy debate is the fact that, with the exception of one study evaluating spinal cord injury,7 research has relied on self-reporting—that is, individuals’ statements about their health and financial affairs, as well as their interpretation of the primary reason that led to their decision to file for bankruptcy.

Furthermore, the observed prevalence of medically related bankruptcy is dependent on the researcher’s definition of medically related. Studies find that between 53 percent8 and 62 percent9–13 of debtors report medical debt at the time of filing for bankruptcy, and 2 percent14 to 50 percent15 indicate that medical problems were the cause of their bankruptcy. Melissa Jacoby and coauthors found that 25 percent of people underreported their medical obligations in bankruptcy court records when compared to information from direct surveys of out-of-pocket medical expenses.16

An additional problem with available studies is that there is no record of the date of onset of the medical condition or conditions reported to be associated with filing for bankruptcy. Thus, the typical time between the onset of serious illness and bankruptcy filing is generally unknown. Of particular relevance to this study, the incidence of and time before bankruptcy filing among the 1.5 million adults diagnosed with cancer in the United States each year is also unknown.

Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to determine the incidence and time course of bankruptcy filings among patients newly diagnosed with cancer. To generate accurate estimates, we linked records from federal bankruptcy records from 1995 through 2009 with both a population-based cancer registry and an age-, sex-, and ZIP code–matched random sample of individuals without cancer from LexisNexis. We were particularly interested in identifying specific cancer types that might be associated with a higher risk of bankruptcy. Additionally, we sought to identify personal factors at the time of cancer diagnosis that might be associated with a person’s risk of filing for bankruptcy.

Study Data And Methods

Study Population

Our study included a populationwide registry of individuals with cancer and a randomly sampled age-, sex-, and ZIP code–matched population of people without cancer. ZIP code matching was used to control for socioeconomic status within a region and regional access to medical care.

Cancer cases were identified using the Cancer Surveillance System of Western Washington, a population-based cancer registry that is part of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER). We included people diagnosed with cancer between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2009. We excluded people who were younger than twenty-one years at the time of the diagnosis, who had in situ stage (very early cancers that has not spread to neighboring tissue) cancer at diagnosis, or who had cancer that was diagnosed only at the time of death.

The control population was identified using the LexisNexis data repository, the largest commercially available repository of public record data in the United States. Information in the repository is drawn from more than 10,000 sources, including white pages listings, voter registration records, personal and real property records, and—through data exchanges—credit card issuers, publishers, and manufacturers. The LexisNexis repository is commonly used for business functions such as deterring and detecting fraud, authenticating and verifying identity, and conducting civil and criminal investigations. As of April 2012 there were 4,532,591 people age eighteen or older from Washington State included in the LexisNexis database, representing 88 percent of the state’s adult population.

To eliminate people with cancer from the LexisNexis cohort, we first linked LexisNexis records with the SEER records using a probabilistic algorithm that included name, sex, address of residence, and month and year of birth. Seven percent of the people from the LexisNexis database were excluded from the study because they had a positive match with the SEER database.

We then matched each patient from the database who met the inclusion criteria above to a person in the noncancer LexisNexis database. The match criteria were year of birth, ZIP code of residence, and sex. Because of the nature of the LexisNexis data we were not able to match the most elderly of patients, and thus we excluded patients over the age of ninety. We found matches for 197,840 (86 percent) of the 228,430 patients who were under ninety-one and eligible in the SEER records. The primary reason for failing to find a match was the inability to find an age- and sex-matched person within the same ZIP code as the patient.

The cancer and control cohorts were both linked with the records of the US Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Washington. The court serves nineteen counties in western Washington, including all thirteen counties in the Cancer Surveillance System of Western Washington, and has complete electronic case files dating from June 1991. We included filings from January 1, 1995, through December 31, 2009. The bankruptcy database includes each debtor’s name and address and bankruptcy filing information, including the type of bankruptcy, number of creditors, and assets and liabilities at the time of bankruptcy. Joint filings are indicated as such, and information on the codebtor is included.

We included only two types of bankruptcy, those covered by Chapter 7 or Chapter 13 of the US Bankruptcy Code. Debtors filing under Chapter 7 typically liquidate eligible assets such as bank accounts, investments, and second cars or homes to pay creditors and then are discharged from their eligible debts—which exclude, for example, child or spousal support and certain income taxes. Under Chapter 13, debtors file a repayment plan to pay back all or a portion of their debts and retain ownership of most of their assets. Seventy percent of personal bankruptcies filed in the United States are Chapter 7 cases,17 although all medical bills are eligible for discharge in a bankruptcy under either Chapter 7 or 13.

We linked SEER records to the bankruptcy records using a probabilistic algorithm that included the debtor’s name, sex, and address of residence, as well as the last four digits of his or her Social Security number. We linked LexisNexis records to the bankruptcy records using a probabilistic algorithm that included name and address of residence. For patients who filed for bankruptcy multiple times, we included only the first filing after their cancer diagnosis.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Analyses

We used Kaplan-Meier analysis to estimate the incidence of bankruptcy for the cancer patient and control populations. Accounting for death allowed us to use multivariate Cox regression analysis to estimate hazard rates for bankruptcy, focusing on cancer diagnosis as the factor of interest.

Separate multivariate Cox regression models were created for all cancer patients combined plus the controls, as well as for each of the nine separate cancer types with the highest incidence of bankruptcy (with a matched control group). In each model the dependent variable was defined as time to first bankruptcy after diagnosis for the cancer cohort and time to first bankruptcy after index date for the control cohort (the index date was the date of diagnosis of the matching cancer case).

Independent variables included marital status and a time-dependent covariate to reflect the date of implementation of the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005. This law, designed to make it more difficult for debtors to file a Chapter 7 or 13 bankruptcy, was passed by Congress on April 14, 2005, and signed into law on April 20 and implemented on October 17 of the same year. Following its enactment, Chapter 7 filings dropped to 57 percent of previous personal bankruptcy filings before returning to previous levels by 2009.17

To account for left truncation, all regression analyses used age as the time scale. That is, age at diagnosis or index date was the start for follow-up. Data on race was not available for the LexisNexis population and therefore could not be included in the model.

Limitations

We note some limitations of our choices for the analysis. Person-level information about individuals’ financial situation at diagnosis was not available. SEER does not collect this information, and financial information is incompletely and inconsistently available in the bankruptcy records. Neither database collects information on health insurance, although it is reasonable to assume that nearly all people age sixty-five or older are insured by Medicare.

Treatment choices may influence bankruptcy risk. Although SEER does collect information on whether patients received surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or hormone therapy, we did not include treatment type in the regression models because treatment choices might have been influenced by patients’ financial situation at the time of diagnosis.

The study was limited to western Washington. Washington State ranks twenty-second of the fifty states in terms of bankruptcy filings per capita, with 5.04 filings per 1,000 people.18

Study Results

Between 1995 and 2009 there were 197,840 people in the western Washington SEER data who were diagnosed with cancer and met the inclusion criteria for our study. During that same time period, 4,408 (2.2 percent) of those people filed for bankruptcy protection after being diagnosed with cancer (83 percent of them under Chapter 7 and 17 percent under Chapter 13). Of the matched 197,840 controls, who were not diagnosed with cancer, 2,291 (1.1 percent) filed for bankruptcy over the same time period (73 percent of them under Chapter 7 and 27 percent under Chapter 13). Compared to cancer patients who did not file for bankruptcy, those who did were more likely to be younger, female, nonwhite, and have localized or regional stage disease (versus distant stage) at diagnosis, using SEER staging criteria (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1.

Demographic And Cancer-Related Characteristics Of Cancer Patients By Bankruptcy Status, Western Washington State, 1995–2009

| Characteristic | Total | Bankruptcy | No Bankruptcy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | n | % | |

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <40 | 14,180 | 7 | 830 | 19 | 13,350 | 7 |

| 40–64 | 96,032 | 49 | 2,751 | 62 | 93,281 | 48 |

| ≥65 | 87,628 | 44 | 827 | 19 | 86,801 | 45 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 98,202 | 50 | 1,945 | 44 | 96,257 | 50 |

| Female | 99,638 | 50 | 2,463 | 56 | 97,175 | 50 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 174,027 | 88 | 3,771 | 86 | 170,256 | 88 |

| Nonwhite | 23,813 | 12 | 637 | 14 | 23,176 | 12 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 117,455 | 59 | 2,579 | 59 | 114,876 | 59 |

| Other/Unknown | 80,385 | 41 | 1,829 | 41 | 78,556 | 41 |

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 170,186 | 86 | 3,655 | 83 | 166,531 | 86 |

| Large rural | 10,620 | 5 | 254 | 6 | 10,366 | 5 |

| Small rural | 4,773 | 2 | 84 | 2 | 4,689 | 2 |

| Isolated | 2,678 | 1 | 39 | 1 | 2,639 | 1 |

| Unknown | 9,583 | 5 | 376 | 9 | 9,207 | 5 |

| Cancer type | ||||||

| Breast | 34,195 | 17 | 1,017 | 23 | 33,178 | 17 |

| Colorectal | 17,244 | 9 | 362 | 8 | 16,882 | 9 |

| Leuk/lymph | 19,743 | 10 | 450 | 10 | 19,293 | 10 |

| Lung | 24,227 | 12 | 280 | 6 | 23,947 | 12 |

| Prostate | 32,966 | 17 | 555 | 13 | 32,411 | 17 |

| Melanoma | 10,750 | 5 | 310 | 7 | 10,440 | 5 |

| Thyroid | 4,980 | 3 | 231 | 5 | 4,749 | 2 |

| Uterine | 6,346 | 3 | 191 | 4 | 6,155 | 3 |

| Other | 47,389 | 24 | 1,012 | 23 | 46,377 | 24 |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||||

| Localized | 98,728 | 50 | 2,588 | 59 | 96,140 | 50 |

| Regional | 43,921 | 22 | 1,119 | 25 | 42,802 | 22 |

| Distant | 46,534 | 24 | 563 | 13 | 45,971 | 24 |

| Unstaged | 8,657 | 4 | 138 | 3 | 8,519 | 4 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis.

NOTES The individual cancer types listed are those with the highest cumulative incidence of bankruptcy among all cancer types examined from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER). Chi-square tests for bankruptcy versus no bankruptcy were significant (p < 0.001) for all characteristics except for marital status (p = 0.24). Leuk/lymph is leukemia/lymphoma.

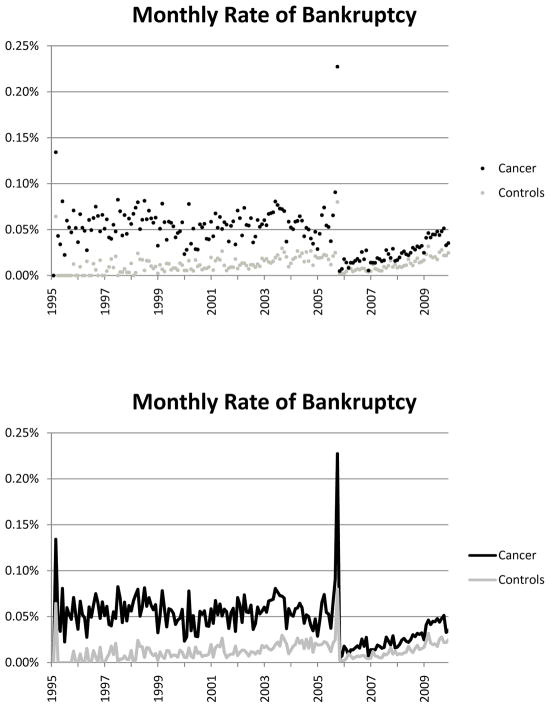

There was a substantial increase in bankruptcy filings, including among cancer patients, in the months leading up to the signing of the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005, followed by a precipitous decline in filings for both cancer patients and people in the control group in the following months (Exhibit 2). This trend held true for both younger and older people. The lowest rates of bankruptcy filing were during 2006–07. In the ensuing years bankruptcy filings increased more quickly than during any previous period, probably because of the financial crisis and recession as well as the adaptation of debtors and bankruptcy professionals to the new law.

Exhibit 2.

Monthly rate of bankruptcies for cancer patients and an age- and gender-matched group without cancer.

The proportion of the cancer cohort that filed for bankruptcy within one year of diagnosis was 0.52 percent, compared to 0.16 percent within one year of the index date for the control group. For bankruptcy filings within five years of diagnosis or index date, the proportion of cancer patients was about 1.7 percent, compared to 0.7 percent for the control group. The incidence rates for bankruptcy at one year after diagnosis, per 1,000 person-years, for the cancers with the highest overall incidence rates were as follows: all cancers 6.1, thyroid 9.3, lung 9.1, uterine 6.8, leukemia/lymphoma 6.2, colorectal 5.9, melanoma 5.7, breast 5.7, and prostate 3.7.

Bankruptcy filing rates differed substantially by age: Younger people with cancer experienced the highest bankruptcy rates across all cancer types (Exhibit 3). In addition, compared to younger cohorts, bankruptcy filing rates were substantially lower for people age sixty-five or older.

Exhibit 3.

Bankruptcy Rates Per 1,000 Person-Years For Cancer Patients And Matched Group Without Cancer, Western Washington State, 1995–2009

| Cancer type | Age (years) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–34 | 35–49 | 50–64 | 65–79 | 80–90 | ||||||

| Cancer | Control | Cancer | Control | Cancer | Control | Cancer | Control | Cancer | Control | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Breast | 13.95 | 3.23 | 7.98 | 3.03 | 4.95 | 2.27 | 2.12 | 0.96 | 1.29 | 0.48 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Colorectal | 11.71 | 1.96 | 9.27 | 2.24 | 5.55 | 2.10 | 2.90 | 0.87 | 1.13 | 0.61 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Leuk/lymph | 9.62 | 2.07 | 9.20 | 3.13 | 5.06 | 1.86 | 3.57 | 1.21 | 0.47 | 0.44 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lung | 2.83 | 0.00 | 12.49 | 2.45 | 8.82 | 2.02 | 5.03 | 0.99 | 1.28 | 0.50 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Melanoma | 8.30 | 3.84 | 7.14 | 2.74 | 3.10 | 2.10 | 1.94 | 0.89 | 1.40 | 0.45 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Prostate | —a | —a | 6.49 | 2.52 | 3.47 | 1.71 | 2.44 | 0.87 | 0.65 | 0.82 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Thyroid | 11.37 | 3.92 | 9.05 | 2.06 | 6.01 | 2.91 | 4.05 | 1.83 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Uterine | 18.02 | 1.77 | 10.45 | 4.93 | 5.33 | 2.27 | 2.96 | 1.06 | 1.51 | 0.45 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Other | 9.53 | 3.33 | 9.19 | 2.46 | 6.45 | 2.04 | 2.88 | 1.03 | 0.62 | 0.58 |

|

| ||||||||||

| All | 10.06 | 3.15 | 8.55 | 2.75 | 5.01 | 2.04 | 2.76 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.57 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis.

NOTES People in the group without cancer were matched to cancer patients by age, sex, and ZIP code of residence. The individual cancer types listed are those with the highest cumulative incidence of bankruptcy among all cancer types examined from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER). Leuk/lymph is leukemia/lymphoma.

In our study, there were no instances of prostate cancer for men under the age of 35.

Across all cancers, the Cox proportional hazards regression model showed that cancer patients had a significantly higher rate of bankruptcy than people without cancer. The probability that a cancer patient would go bankrupt was 2.65 times greater than that of someone without cancer (Exhibit 4). The bankruptcy reform law of 2005 had a strongly negative impact on bankruptcy filings, with filings after 2005 declining to 57 percent of filings before that year. People who were not married were 1.24 times more likely to file for bankruptcy than married people.

Exhibit 4.

Hazard Rates For Bankruptcy Filing Of Cancer Patients And Matched Group Without Cancer, Western Washington State, 1995–2009

| Cancer type | Cancer patients and controls | Cancera | After new bankruptcy lawb | Nonmarriedc | Group-law interactiond |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 395,680 | 2.65 | 0.57 | 1.24 | 0.67 |

| Breast | 68,390 | 2.41 | 0.55 | 1.52 | 0.79 |

| Colorectal | 34,488 | 3.02 | 0.60 | 1.22 | 0.59 |

| Leuk/lymph | 39,486 | 3.00 | 0.67 | 1.11 | 0.53 |

| Lung | 48,454 | 3.80 | 0.61 | 1.16 | 0.59 |

| Melanoma | 21,500 | 2.08 | 0.49 | 1.03 | 0.74 |

| Prostate | 65,932 | 2.32 | 0.49 | 1.30 | 0.75 |

| Thyroid | 9,960 | 3.46 | 0.62 | 1.29 | 0.53 |

| Uterine | 12,692 | 2.28 | 0.47 | 1.36 | 0.92 |

| Other | 94,778 | 2.97 | 0.58 | 1.11 | 0.64 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis.

NOTES Hazard rates were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models and were significantly different from 1 (p = 0.05) except in the following cases: leukemia or lymphoma (leuk/lymph), lung, and melanoma for nonmarried versus married people; and melanoma and uterine for group-law interaction. People in the group without cancer were matched to cancer patients by age, sex, and ZIP code of residence. The individual cancer types listed are those with the highest cumulative incidence of bankruptcy among all cancer types examined from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER).

Reference is no cancer.

Reference is before October 17, 2005, when the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 went into effect.

Reference is married. Nonmarried is single, divorced, widowed, or marital status unknown.

Reference is cancer. This accounts for the differential impact of the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 on those with cancer versus those without cancer.

Across all regression models that considered individual cancer types versus control groups, people with cancer were consistently and significantly more likely to file for bankruptcy than people without cancer, and people in both groups were more likely to file for bankrupt before the law change than after. People with lung cancer were 3.8 times more likely than controls to go bankrupt, a larger difference than was the case with any other type of cancer. The 2005 bankruptcy law had less of an effect on the likelihood of filing among cancer patients than among people without cancer.

Because of the difference in bankruptcy risk by age, we reran the Cox regression models after stratifying the two groups into people age sixty-five or older and those younger than sixty-five. Because of the change in bankruptcy laws, we also reran the Cox regression models with only those patients who were diagnosed after the new bankruptcy law took effect. The hazard ratios for cancer and bankruptcy risk did not change appreciably in either cohort in these separate analyses.

Discussion

Linking SEER and federal bankruptcy records for the period 1995–2009, we found that cancer patients had a rate of bankruptcy that was 2.65 times higher than people without cancer. Furthermore, the rate appeared to vary across cancer types, with notably higher rates for patients with thyroid cancer. This may be because thyroid cancer affects younger women more often than other cancers do.19 Compared to men, younger women are more likely to live in single-income households and to have lower wages and lower rates of employment, and therefore less access to high-quality health insurance—leaving them more financially vulnerable.

Finally, it is notable that among people with cancer, the youngest age groups had up to ten times the rate of bankruptcy that older age groups had. Although most households have some control over their “financial health” over time, cancer is generally a sudden and unexpected event. In this context, the risk of bankruptcy will be influenced by the following factors: debt load before the illness, assets, presence and terms of the patient’s health and disability insurance, number of dependent children, and incomes of others in the household at the time of the cancer diagnosis.20

The youngest cohorts in our study were diagnosed at a time when their debt-to-income ratios are typically highest—often unavoidably, because they are paying off student loans, purchasing a home, or starting a business. All working-age people who develop cancer face loss of income and, in many cases, loss of employer-sponsored insurance, both of which can be devastating for households in which the patient is the primary wage earner. As noted above, studies have shown that 40–85 percent of cancer patients stopped working during their initial cancer treatment, with some being absent from work for nearly six months.5

In contrast, people age sixty-five or older generally have Medicare insurance and Social Security benefits. These older people are likely to have more assets and possibly more income than working-age people. However, it is likely that having stable insurance (specifically, coverage not tied to employment) plays a major role in mitigating the risk of bankruptcy for those over age sixty-five.

The Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005, the most substantial revision of the US bankruptcy laws since 1978, had a profound impact on bankruptcy filings. The number of personal bankruptcies filed rose from approximately 1.0–1.4 million per year to more than 2.0 million in 2005.21,22 The year following enactment of the new law, filings fell to less than 600,000. By 2009, the end of our study period, bankruptcy rates for cancer patients were approaching levels seen prior to implementation of the 2005 bankruptcy law, with a strong upward trend.22

Many provisions in the 2005 bankruptcy law were aimed at reducing so-called frivolous filings among those with past financial indiscretions who were seeking an easy way to discharge their debts.23 Clearly, people experiencing a major health event such as cancer do not fall in this category. Most courts and legal representatives counsel individuals not to file for bankruptcy until the issue causing financial distress is resolved. Shortly before the 2005 bankruptcy law was implemented, it is likely that the uncertainty surrounding the new law caused many debtors to file for bankruptcy, and those who had cancer were probably also motivated by the uncertainty regarding the outcome of their illness.11 All of the October 2005 bankruptcy filings in our study occurred prior to October 17, when the new law took effect.

It is likely that substantial proportions of the people who filed “early”—that is, before their cancer therapy was completed—remained at risk of incurring new medical debt after the bankruptcy discharged their existing debt. In the two months following the enactment of the bankruptcy law, only ten cancer patients in our study filed for bankruptcy (2 percent of yearly filings), as opposed to sixty-two filings (14 percent) in the same period in 2004. This difference suggests that cancer patients indeed may have filed earlier than planned because of the uncertainties created by the new law.

This study found strong evidence of a link between cancer diagnosis and increased risk of bankruptcy. Although the risk of bankruptcy for cancer patients is relatively low in absolute terms, bankruptcy represents an extreme manifestation of what is probably a larger picture of economic hardship for cancer patients. Our study thus raises important questions about the factors underlying the relationship between cancer and financial hardship.

Future studies that include information on patients’ financial and insurance status at the time of diagnosis and throughout their treatment will be needed to fully understand the relationship among cancer, financial difficulties, and bankruptcy. Also important is the impact of cancer on the patient’s ability to remain employed, since most health insurance is obtained through the workplace.24 These factors are particularly important in younger working-age populations, in which employment, income, insurance status, and personal assets vary substantially.

Conclusion

We believe that cancer care facilities and oncology practitioners should assess the financial health of their patients as a matter of course. Because temporary inability to work is often unavoidable during therapy, patients and their families should be encouraged to make financial preparations to the extent that they are possible. More generally, this study underlines the importance for cancer care providers of carefully considering the use of services that have limited evidence of substantial benefit and potential high out-of-pocket costs.

As a policy issue, there may be a role for employers and governments in creating programs or incentives to reduce the likelihood of financial insolvency, given that bankruptcies are “lose-lose” events for debtors and creditors alike. An example would be tax incentives to encourage employers to provide supplemental insurance policies that provide fixed sums to cover household and out-of-pocket expenses in the first year following a cancer diagnosis.

Finally, future studies of cancer patients who declare bankruptcy should examine the impact of this event on their cancer-related outcomes and later ability to obtain health insurance and access to health care.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health (grant no. RC1 MD004135). The sponsor had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge Bryan Comstock and Kristin Wyatt for additional statistical analysis and Tiffany Janes for her invaluable assistance at the Cancer Surveillance System of Western Washington.

Biographies

Ramsey is the director of the Hutchinson Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research based in the Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. He is also a professor of medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine; adjunct professor, Department of Health Services; adjunct professor, Institute for Public Health Genetics, School of Public Health; and adjunct professor, Pharmaceutical Outcomes, Research, and Policy Program, Department of Pharmacy, at the University of Washington.

Additionally, Ramsey is a staff physician at the University of Washington Medical Center. He earned a doctorate in health economics from the University of Pennsylvania and a medical degree from the University of Iowa.

David Blough is a research associate professor in the Department of Pharmacy, University of Washington, and a faculty member in the university’s Pharmaceutical Outcomes Research and Policy Program. He also serves as an affiliate investigator in the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center as well as an instructor in educational outreach at the University of Washington. Blough earned a master’s degree in mathematics from the University of Arizona and both a master’s degree and doctorate in statistics from Iowa State University.

Anne Kirchhoff is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) investigator. She is a member of the Cancer Control and Population Sciences Research Program at HCI. Kirchhoff investigates the social and financial consequences of cancer, primarily in survivors of childhood cancer. She earned a master’s degree in public health from the Saint Louis University and a doctorate in health services, with a concentration in biobehavioral cancer prevention and control, from the University of Washington.

Karma Kreizenbeck is the project director for the Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. She directs multiple projects focused on health economics, disparities, and outcomes research in cancer, and she manages the stakeholder and community advisory engagement process. Kreizenbeck earned a bachelor’s degree in history from Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

Catherine Fedorenko is a systems analyst programmer at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Her responsibilities include managing data analysis team needs; creating programs to complete statistical analyses for health care studies; and contributing to the preparation and writing of abstracts, posters, and papers. She was earned a master’s degree in management sciences from the University of Waterloo, in Ontario, Canada.

Kyle Snell was a project coordinator at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center during the writing of this article, and he is now a software engineer at Crowdtap, a company that enables marketers to partner with consumers throughout the marketing process. He earned a master’s degree in integrated biosciences from the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities.

Polly Newcomb is the program head of the Cancer Prevention Program at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; senior scientist at the Carbone Cancer Center, University of Wisconsin; and research professor in the Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Washington. Newcomb earned a master’s degree in public health and a doctorate in epidemiology from the University of Washington. She received the 2013 American Society of Preventive Oncology Distinguished Achievement Award.

William Hollingworth is a professor of health economics, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, in the United Kingdom. He earned a master’s degree in health services and public health research from the University of Aberdeen, a master’s degree in health economics from the University of York, and a doctorate in health services research from the University of Cambridge, Darwin College, all in the United Kingdom.

Karen Overstreet is the chief judge for the US Bankruptcy Court, Western District of Washington, in the City of Seattle. She received a law degree from the University of Oregon.

Footnotes

In this month’s Health Affairs, Scott Ramsey and coauthors report on the the relationship between receiving a cancer diagnosis and filing for bankruptcy.

The authors have no conflicts of interest specific to the topic of this article.

Notes

- 1.Howard DH, Molinari NA, Thorpe KE. National estimates of medical costs incurred by nonelderly cancer patients. Cancer. 2004;100(5):883–91. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arozullah AM, Calhoun EA, Wolf M, Finley DK, Fitzner KA, Heckinger EA, et al. The financial burden of cancer: estimates from a study of insured women with breast cancer. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(3):271–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finkelstein EA, Tangka FK, Trogdon JG, Sabatino SA, Richardson LC. The personal financial burden of cancer for the working-aged population. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(11):801–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Boer AG, Taskila T, Ojajarvi A, van Dijk FJ, Verbeek JH. Cancer survivors and unemployment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA. 2009;301(7):753–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Short PF, Vasey JJ, Tunceli K. Employment pathways in a large cohort of adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;103(6):1292–301. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chirikos TN, Russell-Jacobs A, Cantor AB. Indirect economic effects of long-term breast cancer survival. Cancer Pract. 2002;10(5):248–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.105004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollingworth W, Relyea-Chew A, Comstock BA, Overstreet KA, Jarvik JG. The risk of bankruptcy before and after brain or spinal cord injury: a glimpse of the iceberg’s tip. Med Care. 2007;45(8):702–11. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318041f765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shuchman P. New Jersey debtors 1982–1983: an empirical study. Seton Hall Law Rev. 1985;15:541–92. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sittner L, Grummert S, Potthoff CJ, Lyman ED. Medical expense as a factor in bankruptcy. Nebr State Med J. 1967;52(9):412–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E, Woolhandler S. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):741–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Woolhandler S. Medical bankruptcy in Massachusetts: has health reform made a difference? Am J Med. 2011;124(3):224–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Relyea-Chew A, Hollingworth W, Chan L, Comstock BA, Overstreet KA, Jarvik JG. Personal bankruptcy after traumatic brain or spinal cord injury: the role of medical debt. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(3):413–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorne D. The (interconnected) reasons elder Americans file consumer bankruptcy. J Aging Soc Policy. 2010;22(2):188–206. doi: 10.1080/08959421003621093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan TA, Warren E, Westbrook JL. As we forgive our debtors: bankruptcy and consumer credit in America. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovac SD. Judgment-proof debtors in bankruptcy. American Bankruptcy Law Journal. 1991;65:675–76. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacoby MB, Holman M. Managing medical bills on the brink of bankruptcy. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2010;10(2):239–89. 291–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Courts. Bankruptcy filings per capita, 12 month period ending December, 2011 [Internet] City (State): Publisher; 2011. [cited 2013 Apr ??]. Available from: URL. [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Courts. Bankruptcy filings per capita, by US County: September 30, 2006 [Internet] Washington (DC): US Courts; [cited 2013 Apr 26]. Available from: http://www.uscourts.gov/Statistics/BankruptcyStatistics/BankruptcyFilingsPerCapita.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cancer Institute, Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Thyroid [Internet] Bethesda (MD): The Institute; [cited 2013 Apr 26]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/thyro.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warren E. Bankrupt children. Minn Law Rev. 2002;86(5):1003, 1009–11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han S, Keys BJ, Li G. Credit supply to personal bankruptcy filers: evidence from credit card mailings [Internet] Washington (DC): Federal Reserve Board; 2011. May, [cited 2013 Apr 26]. (Finance and Economics Discussion Series: 2011-29). Available from: http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2011/201129/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.White MJ. Bankruptcy reform and credit cards [Internet] Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2007. Jul, [cited 2013 Apr 26]. (Working Paper 13265). Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w13265.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landry AY, Landry RJ. Medical bankruptcy reform: a fallacy of composition. American Bankruptcy Institute Law Review. 2011;19:151–83. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradley CJ, Bednarek HL, Neumark D. Breast cancer survival, work, and earnings. J Health Econ. 2002;21(5):757–79. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]