Abstract

Background The hemi-transeptal (Hemi-T) approach was developed to facilitate a binasal two-surgeon endoscopic approach for sellar tumors, with preservation of the nasoseptal flap and selective mobilization for reconstruction.

Methods A retrospective case-control study was performed comparing the Hemi-T approach with previously used methods of sellar exposure and reconstruction. Outcome measures included operative time and postoperative nasal morbidity.

Results A total of 23 patients underwent the Hemi-T approach versus 42 in whom traditional exposure was performed. Operative time was significantly shorter using the Hemi-T technique (152.6 ± 56.8 versus 205.2 ± 61.3 minutes; p = 0.001), as was the length of hospital stay (3.3 ± 1.9 versus 5.4 ± 3.6 days; p = 0.004). There was no difference in the rates of intraoperative or postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak, cartilage necrosis, septal perforation, or mucosal adhesions.

Conclusion The Hemi-T approach facilitates binasal two-surgeon access to the sella without compromise of the pedicle during the extended sphenoidotomies and tumor removal. Operative time and nasal morbidity is not increased, and iatrogenic injury to the nasal cavity is minimized when a flap is not required.

Keywords: skull base defect, CSF rhinorrhea, endoscopic skull base surgery, reconstruction, nasoseptal flap

Introduction

The endoscopic endonasal approach to the skull base is an established technique that has facilitated the safe removal of a variety of benign and malignant cranial base tumors. The nasoseptal flap (NSF) has dramatically reduced the rate of postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage.1 There are drawbacks of NSF harvest, however, including increased surgical time, prolonged crusting of the donor site, septal cartilage necrosis, nasal obstruction, synechiae, and decreased olfaction.2 In certain situations such as skull base meningiomas and other intradural pathologies, anticipation of dural reconstruction is obvious and an NSF is typically harvested at the outset of surgery. In other pathologies, such as pituitary adenoma surgery, flap reconstruction is not always necessary, and this is difficult to predict prior to tumor removal. Since September 2012, we have refined a technique of routine hemi-transeptal (Hemi-T) access to the sphenoid sinus and sella turcica for pituitary adenoma surgery, which we describe in this article. The principal advantages include avoiding devascularization of the flap pedicle during the approach, availability of a large flap in cases of intraoperative CSF leakage, and the avoidance of flap harvest if it is not required at the end of the tumor resection. In this article, we describe the surgical technique of the hemi-transeptal approach, as well as compare outcomes such as postoperative CSF leak rates, operative time, flap-related morbidity, and patient-experienced nasal morbidity between this and the traditional endoscopic transsphenoidal approach.

Methods

Study Design

The study design is a retrospective case-control study comparing two endoscopic approaches for pituitary adenoma surgery performed during two time periods. The traditional technique was performed on patients operated on between October 2010 and October 2012, in which a standard endoscopic transnasal approach to the sphenoid sinus, with a posterior septectomy and attempted sparing of one posterior septal vascular pedicle in a method similar to that described by Rivera-Serrano et al3 was performed. The Hemi-T technique was applied to patients operated on from May 2012 to April 2013; the technique is described here. Patients with pathology- proven pituitary adenomas or sellar Rathke cleft cysts were included, regardless of the size of the tumor. Patients harboring other pathologies (e.g., chordoma, meningioma, and giant sellar/suprasellar cysts or craniopharyngiomas) were excluded. Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to the onset of this study (McGill University institutional review board protocol number 12-235 SDR).

Hemi-transeptal Flap Technique

The nasal septum and posterolateral nasal walls are injected with Xylocaine 1% and adrenaline 1:100,000, and cotton patties soaked in topical adrenaline 1:1000, with or without 4% cocaine, are used for mucosal decongestion. The middle turbinates are lateralized bilaterally; the superior turbinate is only lateralized on the side of the septal incision.

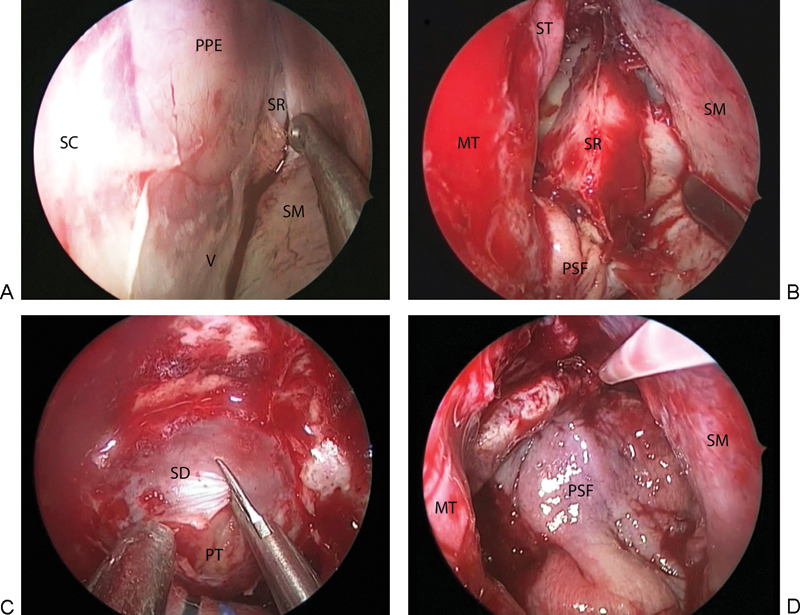

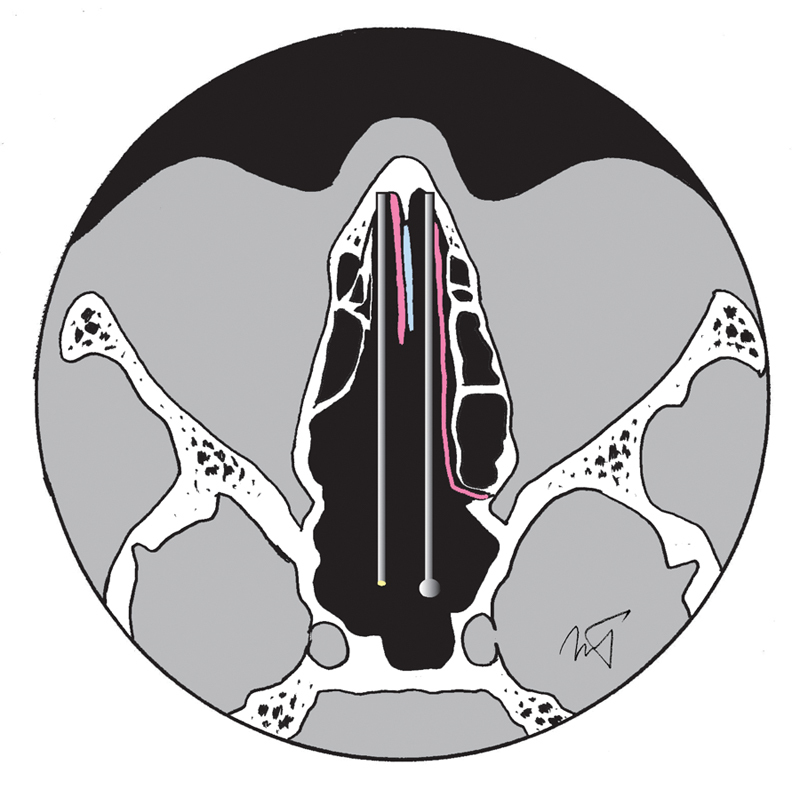

A Killian incision is typically performed on the left side, assuming there is no septal spur or deviation, and a sub-mucoperichondrial/mucoperiosteal dissection is initialized. This is developed posteriorly until the rostrum of the sphenoid (Fig. 1A) and the sphenoid ostium are visualized under the mucosal flap. This flap remains attached to the septum only at its superior and inferior margins. A cut is then made in the osteocartilaginous junction, and the bony septum is removed. To access the contralateral nasal cavity and allow a binasal approach, a mucoperiosteal flap with its corresponding vascular pedicle is fashioned with a extended needle tip monopolar cautery. This is mobilized into the nasopharynx for use during reconstruction, allowing preservation of vascularized mucosal tissue (Fig. 1B). At this point, the superior turbinate and posterior ethmoid cells contralateral to the initial Killian incision are resected, wide bilateral sphenoidotomies are performed, and the pituitary surgery performed (Fig. 1C). This technique allows instruments to access the sphenoid from both nostrils during the pituitary portion of the operation, facilitating bimanual surgical technique, with minimal dissection of the left nasal cavity and without devascularization of any mucosal vascular pedicles (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Intraoperative views of the hemi-transseptal technique. (A) Elevation of the septal mucosa on the left side up to the anterior face of the sphenoid. (B) Exposure of the sphenoid rostrum following removal of the bony septum and creation of a right-sided flap using the posterior septal mucosa. (C) Bimanual access to the sella turcica for resection of the pituitary tumor. (D) Reconstruction of the sellar defect using the right-sided posterior septal flap. MT, middle turbinate; PPE, perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone; PSF, posterior septal flap; PT, pituitary tumor; SC, septal cartilage; SD, sella dura; SM, septal mucosa; SR, sphenoid rostrum; V, vomer.

Fig. 2.

Diagram illustrating the binostril access to the sphenoid and sella turcica using the Hemi-transseptal approach, in an axial plane, with the complete left and anterior right septal mucosa preserved (pink) and septal cartilage shown in blue; note that the right-sided posterior septal mucosa was fashioned into a flap and tucked into the nasopharynx for use in reconstruction (not shown).

At the end of surgery, the right-sided posterior septum mucosal flap is rotated over the sellar reconstruction (Fig. 1D). In most pituitary procedures, this is sufficient to cover the defect, even if a CSF leak is encountered. However, if a larger defect is created during the tumor resection (say, extending to the planum sphenoidale or ethmoid fovea), a full-length nasoseptal flap can easily be harvested from the left side. If it is not required, as in most pituitary operations, the flap is repositioned on the remaining septal wall and sutured with an absorbable running stitch. Note that the mucosa of the sphenoid floor is removed centrally before laying down the flap.

Data Collection

Our primary outcome measures were postoperative CSF leak rates and patient-reported nasal morbidity. Secondary outcome measures included surgical operative time and 2-week appearance of the nasal mucosa including the presence of nasal crusting, synechiae, septal perforations, and cartilage necrosis. Also documented was duration of hospital stay. Presence of absence of intraoperative CSF leakage were recorded based on operative notes for all cases, as well as type of repair and use of additional techniques such as fascia lata harvest or lumbar drain insertion. Baseline endocrinologic and ophthalmologic assessments were performed for all patients before surgery and generally at 3 and 6 months postoperatively. All patients had magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the sella as well as brain computed tomography for navigation purposes. Follow-up MRI was generally obtained 3 to 6 months postoperatively, and annually thereafter. Clinical follow-up visits with ear, nose, and throat (C.J.V., M.A.T., and A.Z.) and neurosurgery departments (D.S. and S.D.) were routinely performed at 2 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and annually thereafter in the absence of persistent postoperative issues. All patients were followed for at least 4 months postoperatively and underwent endoscopic debridement at the follow-up visits.

Statistics

Baseline characteristics, CSF leak rates, and complications were compiled on a master database, and the different approaches were compared using chi-square or t test analysis with 95% confidence intervals. IBM SPSS v.21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, United States) was used for statistical analysis. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

From August 2010 to April 2013, 65 patients underwent an endoscopic resection of pituitary adenoma or intrasellar RCC, of which 23 reconstructions were performed using the Hemi-T technique. Mean age was 50.6 ± 14.2 years (range: 18–80 years). Mean follow-up for the entire cohort was 14.6 ± 8.8 months (range: 1.1–32.8 months). Pathologic diagnoses included 32 nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas, 23 functioning adenomas, 5 Rathke cleft cysts, and 4 apoplectic tumors. Baseline demographic data and results are included in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic outcome data for patients who underwent the hemi-transseptal and traditional approaches for pituitary tumor resection.

| Hemi-transseptal | Traditional technique | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 23 | 42 | |

| Age, y | 50.7 ± 13.7 | 52.3 ± 14.6 | NS |

| Sex | 11 F/12 M | 26 F/16 M | NS |

| Follow-up, mo | 6.7 ± 3.3 | 18.8 ± 7.9 | p < 0.0001 |

| Operative time, min | 152.6 ± 56.8 | 205.2 ± 61.3 | p = 0.001 |

| Hospital stay, d | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 5.4 ± 3.6 | p = 0.004 |

| Intraoperative CSF leak (%) | 4/23 (17.4) | 12/42 (28.6) | NS |

| Postoperative CSF leak (%) | 1/23 (4.3) | 5/42 (11.9) | NS |

| Fascia lata harvest (%) | 2/23 (8.6) | 14/42 (33.3) | p = 0.033 |

| Septal perforation (%) | 2/23 (8.7) | 2/42 (3.8) | NS |

| Cartilage necrosis (%) | 1/23 (4.3) | 1/42 (2.3) | NS |

| Mucosal adhesions (%) | 7/23 (30.4) | 8/42 (19) | NS |

Abbreviation: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; NS, not significant.

Operative time when the Hemi-T approach was used was shorter than with a traditional approach (152.6 ± 56.8 versus 205.2 ± 61.3 minutes; p = 0.001), as was the duration of hospitalization (3.3 ± 1.9 versus 5.4 ± 3.6 days; p = 0.004). Both intra- and postoperative CSF leak rates were not significantly different between techniques. When a CSF leak was encountered, reconstruction with an inlay and overlay of fascia lata was performed, which was then covered with the right posterior septal mucosal flap. Fascia lata was harvested more frequently when the traditional approach was used (Table 1). Additionally, operative time was shorter with the Hemi-T approach, even when fascia lata was required (164.4 ± 49.9 minutes versus 236.9 ± 70.8 minutes; p < 0.0001). There was one patient in the Hemi-T group who had a postoperative CSF leak; on revision it was noted that the anterior edge of fascia lata had displaced, and the leak resolved following repair and repositioning of the flap. In all cases, we rotated the right small septal flap over the sellar reconstruction and the left septal mucosa was repositioned back to the septum.

The rate of septal perforation, cartilage necrosis, and synechiae formation was not significantly different between the Hemi-T and traditional approaches, based on an initial 2-week postoperative endoscopic examination in the clinic, and at last follow-up (Table 1).

Discussion

Reconstructive techniques during endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery vary considerably, each with relative advantages and disadvantages. For transsphenoidal pituitary surgery, the primary indication for sellar reconstruction is to prevent a postoperative CSF leak. Clearly, the most important predictor of postoperative CSF leak is an intraoperative CSF leak.4 For transsphenoidal surgery, the rate of intraoperative CSF leakage reported in the literature ranges widely from 0.2 to 58%.5 Other factors that influence this rate include an elevated body mass index,6 follicle-stimulating hormone–7 and adrenocorticotropic hormone–secreting adenomas,7 8 prior transsphenoidal surgery, and prior radiotherapy.8

Most surgeons generally do not perform elaborate closures of the sella when an intraoperative CSF leak is not encountered.5 9 10 For intraoperative CSF leaks, numerous types of repair have been reported since Hardy's description in the 1970s,11 in part influenced by the grade of intraoperative CSF leak12 and/or whether an extended endonasal approach was implemented.13 Reported materials and techniques for sellar reconstruction when there is an intraoperative CSF leak include packing the sella or sphenoid sinus, or both, with autologous fat,10 14 fascia, resorbable Vicryl patches and gelatin foam,15 16 collagen sponge,17 or fleece18; the use of dural substitutes such as expanded polytetrafluoroethylene19 or polyester-silicone20; various nasal mucosal flaps21 22; buttressed by titanium plates23 or bone/cartilage10 or with substances such as BioGlue (CryoLife, Inc., Atlanta, Georgia, United States),24 fibrin glue (Beriplast, Aventis Behringer, Marburg, Germany),25 and hydrogel sealant (DuraSeal, Confluent Surgical, United States).26 Some authors buttress their repair with a balloon packing.27 Additionally, several authors describe continuous lumbar CSF drainage for 3 to 5 days postoperatively.25 Although there is no uniform agreement regarding sellar reconstruction, multilayered closure of the skull base defect is the gold standard of reconstructive techniques, with or without the addition of a vascularized flap.28 29

The introduction of the NSF has dramatically reduced postoperative CSF leak rates from 20% to < 5% following expanded endoscopic skull base surgery.1 2 30 However, it is associated with a number of potential drawbacks including prolonged crusting of the donor site, septal cartilage necrosis, nasal obstruction, synechiae, and decreased olfaction.2 Furthermore, the decision to raise the flap is often taken at the initiation of surgery in order not to damage the vascular pedicle when performing extended sphenoidotomies.1 Furthermore, when binasal bimanual dissection is desired, both vascular pedicles off the sphenopalatine arteries are at risk.

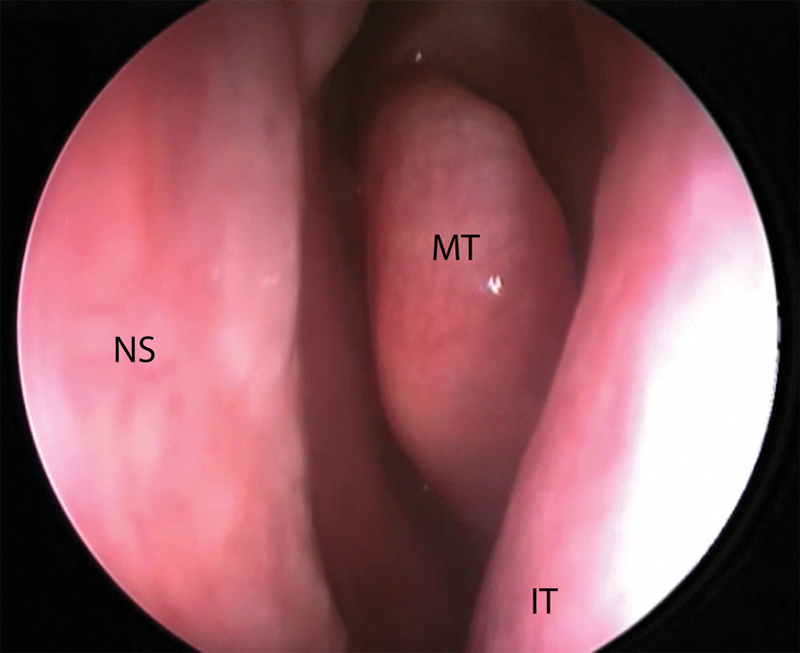

The Hemi-T approach for pituitary surgery described in this article has a number of advantages. A binasal access to the sella for bimanual dissection is obtained, without injuring the right or left vascular pedicle. If the decision is made not to use a NSF, the patient is not submitted to the nasal morbidity of a full-flap harvest. The nasal cavity through instruments are passed deep to the septal mucosa is completed untouched and typically appears normal on early postoperative rhinoscopy (Fig. 3). By being able to perform wide sphenoidotomies, the working space is maximized. Even tumors that extend laterally into the cavernous sinus can be approached, although the use of a 30-degree endoscope may maximize visualization. Operative time is significantly reduced compared with traditional methods. A lumbar drain is not used postoperatively, and in many instances; autologous fascia lata or fat harvest is avoided.

Fig. 3.

Endoscopic view of the undissected left nasal cavity taken at the 2-week postoperative visit. IT, inferior turbinate; MT, middle turbinate; NS, nasal septum.

Other groups have outlined similar techniques for selective NSF harvest during pituitary surgery, preserving the vascular pedicle. Rivera-Serrano and colleagues3 describe a “rescue” flap, in which only the superior and posterior incisions of the NSF are performed initially, reserving the inferior incision when a flap is required after tumor resection. Rawal et al31 describe a similar rescue flap that keeps the septal mucosa along the nasal floor during tumor removal. We (and several other groups) used this technique early in our experience; however, we found that this approach limited our access during tumor removal.

There are a number of limitations with the current study. Inherent sources of bias are related to the retrospective case-control study design, differences due to surgical learning curves, and a relatively short follow-up period. Furthermore, because the a priori rate of CSF leak with pituitary adenoma surgery is low, the study is vulnerable to being underpowered to detect differences between surgical techniques. Nonetheless, we believe the technical advantages of the Hemi-T approach far outweigh any of its drawbacks and have adopted this technique as an initial approach in all endoscopic transsphenoidal surgeries including select extended cases such as planum sphenoidale meningiomas. Future studies should include objective measurements of sinonasal function in the early and late postoperative periods including quality-of-life instruments.

Conclusion

In this retrospective series, the Hemi-T approach was associated with shorter operative time compared with traditional approaches, a lower frequency of fascia lata harvest, and a similar rate of postoperative CSF leak and nasal complications compared with traditional techniques. This technique allows for bilateral preservation of the NSF vascular pedicle during routine exposures of the sella and permits selective reconstruction of the sella with an NSF while facilitating binasal access for a bimanual surgical technique. In cases where an NSF is not required, there is minimal nasal cavity dissection and reduced healing time.

I, Marc A. Tewfik, corresponding author, confirm that I had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication

References

- 1.Hadad G, Bassagasteguy L, Carrau R L. et al. A novel reconstructive technique after endoscopic expanded endonasal approaches: vascular pedicle nasoseptal flap. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(10):1882–1886. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000234933.37779.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassam A B Thomas A Carrau R L et al. Endoscopic reconstruction of the cranial base using a pedicled nasoseptal flap Neurosurgery 200863101ONS44–ONS52.; discussion ONS52–ONS53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rivera-Serrano C M, Snyderman C H, Gardner P. et al. Nasoseptal “rescue” flap: a novel modification of the nasoseptal flap technique for pituitary surgery. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(5):990–993. doi: 10.1002/lary.21419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta G U, Oldfield E H. Prevention of intraoperative cerebrospinal fluid leaks by lumbar cerebrospinal fluid drainage during surgery for pituitary macroadenomas. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(6):1299–1303. doi: 10.3171/2012.3.JNS112160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senior B A, Ebert C S, Bednarski K K. et al. Minimally invasive pituitary surgery. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(10):1842–1855. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817e2c43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dlouhy B J, Madhavan K, Clinger J D. et al. Elevated body mass index and risk of postoperative CSF leak following transsphenoidal surgery. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(6):1311–1317. doi: 10.3171/2012.2.JNS111837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han Z L, He D S, Mao Z G, Wang H J. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea following trans-sphenoidal pituitary macroadenoma surgery: experience from 592 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110(6):570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishioka H Haraoka J Ikeda Y Risk factors of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea following transsphenoidal surgery Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005147111163–1166.; discussion 1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cappabianca P Cavallo L M Esposito F Valente V De Divitiis E Sellar repair in endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery: results of 170 cases Neurosurgery 20025161365–1371.; discussion 1371–1372 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couldwell W T, Kan P, Weiss M H. Simple closure following transsphenoidal surgery. Technical note. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20(3):E11. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.3.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardy J. Transsphenoidal hypophysectomy. J Neurosurg. 1971;34(4):582–594. doi: 10.3171/jns.1971.34.4.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esposito F Dusick J R Fatemi N Kelly D F Graded repair of cranial base defects and cerebrospinal fluid leaks in transsphenoidal surgery Neurosurgery 200760402295–303.; discussion 303–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Maio S, Cavallo L M, Esposito F, Stagno V, Corriero O V, Cappabianca P. Extended endoscopic endonasal approach for selected pituitary adenomas: early experience. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(2):345–353. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.JNS10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spaziante R, de Divitiis E, Cappabianca P. Reconstruction of the pituitary fossa in transsphenoidal surgery: an experience of 140 cases. Neurosurgery. 1985;17(3):453–458. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seiler R W, Mariani L. Sellar reconstruction with resorbable Vicryl patches, gelatin foam, and fibrin glue in transsphenoidal surgery: a 10-year experience with 376 patients. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(5):762–765. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.5.0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin J, Su C B, Xu Z Q, Xia X W, Song F. Reconstruction of the sellar floor following transsphenoidal surgery using gelatin foam and fibrin glue. Chin Med Sci J. 2005;20(3):198–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly D F Oskouian R J Fineman I Collagen sponge repair of small cerebrospinal fluid leaks obviates tissue grafts and cerebrospinal fluid diversion after pituitary surgery Neurosurgery 2001494885–889.; discussion 889–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cappabianca P Cavallo L M Valente V et al. Sellar repair with fibrin sealant and collagen fleece after endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery Surg Neurol 2004623227–233.; discussion 233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman J H Pouratian N Okonkwo D O Jane J A Jr Laws E R Reconstruction of the sellar dura in transsphenoidal surgery using an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene dural substitute Surg Neurol 200869173–76.; discussion 76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cappabianca P Cavallo L M Mariniello G de Divitiis O Romero A D de Divitiis E Easy sellar reconstruction in endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery with polyester-silicone dural substitute and fibrin glue: technical note Neurosurgery 2001492473–475.; discussion 475–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Banhawy O A, Halaka A N, El-Dien A E, Ayad H. Sellar floor reconstruction with nasal turbinate tissue after endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenomas. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2003;46(5):289–292. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubo S Inui T Hasegawa H Yoshimine T Repair of intractable cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea with mucosal flaps and recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor: technical case report Neurosurgery 2005563E627; discussion E627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arita K, Kurisu K, Tominaga A. et al. Size-adjustable titanium plate for reconstruction of the sella turcica. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1999;91(6):1055–1057. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.6.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dusick J R Mattozo C A Esposito F Kelly D F BioGlue for prevention of postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leaks in transsphenoidal surgery: A case series Surg Neurol 2006664371–376.; discussion 376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seda L Camara R B Cukiert A Burattini J A Mariani P P Sellar floor reconstruction after transsphenoidal surgery using fibrin glue without grafting or implants: technical note Surg Neurol 200666146–49.; discussion 49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y Y, Kearney T, Gnanalingham K K. Low-grade CSF leaks in endoscopic trans-sphenoidal pituitary surgery: efficacy of a simple and fully synthetic repair with a hydrogel sealant. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153(4):815–822. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0862-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kassam A, Carrau R L, Snyderman C H, Gardner P, Mintz A. Evolution of reconstructive techniques following endoscopic expanded endonasal approaches. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(1):E8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaberg M R, Anand V K, Schwartz T H. 10 pearls for safe endoscopic skull base surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010;43(4):945–954. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zanation A M, Thorp B D, Parmar P, Harvey R J. Reconstructive options for endoscopic skull base surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44(5):1201–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zanation A M, Carrau R L, Snyderman C H. et al. Nasoseptal flap reconstruction of high flow intraoperative cerebral spinal fluid leaks during endoscopic skull base surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23(5):518–521. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rawal R B, Kimple A J, Dugar D R, Zanation A M. Minimizing morbidity in endoscopic pituitary surgery: outcomes of the novel nasoseptal rescue flap technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147(3):434–437. doi: 10.1177/0194599812443042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]