Abstract

This study determined whether increasing stimulus duration for patients with schizophrenia normalized late Event Related Potentials (ERPs) associated with modulation of response to emotion-evoking stimuli. These ERPs are decreased in patients versus healthy controls when both view stimuli of the same duration.Subjects viewed pictures of hands and judged whether the events depicted were painful or non-painful. Pictures were presented to patients for 500 or 800ms and to healthy controls for 200 or 500ms. Participants were 19 adult outpatients meeting DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and 18 healthy controls, as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview. ERPs to neutral stimuli during a 350-900ms window following stimulus onset were subtracted from ERPs during this same response window to pain stimuli. The area under this difference wave reflected the degree of pain-related positivity and was the dependent measure for analysis. Patient late-positive ERP responses following 500 and 800ms stimuli were highly similar to responses in healthy controls following 200 and 500ms stimuli respectively. Patients and controls differed significantly when responses to 500ms stimuli were compared. People with schizophrenia are known to process information more slowly than healthy people. Our results indicate that slowed early processing of sensory input may limit engagement of higher cognitive and regulatory processes in patients with schizophrenia. This may be one reason self-regulation is compromised in patients, and may help explain why measures of slowed information processing account for so much variance in other cognitive deficits in schizophrenia.

Keywords: Speed of information processing, emotion regulation, Late Positive Potential, P3

1 Introduction

People with schizophrenia show decreased speed of information processing on tasks ranging from repetitive motor movements and simple and choice reaction time to more complex timed tasks like the digit symbol substitution task (DSST). Meta-analysis indicates that patient deficits are greater on the DSST than any other measure of cognition (Dickinson et al., 2007). Deficits were pronounced both in patients on and off medication, although higher dose was associated with slower processing (Knowles et al., 2010). Significant differences between patients and controls on measures of attention, memory and problem solving disappear when results on the DSST are added as a covariate (Rodriguez-Sanchez et al., 2007) and a processing speed index fully mediated the effects of verbal memory on functional outcomes (Ojeda et al., 2008).

Patients with schizophrenia have repeatedly been shown to have reduced amplitude of late ERP components (Ergen et al., 2008; Kuperberg et al., 2011; Pfefferbaum et al., 1989; Strauss et al., 2013; Turetsky et al., 2007). In healthy subjects, the amplitude of these components can be affected by the duration and intensity of the stimulus. We hypothesized that if patients were slower at processing visual input, then stimuli of equal duration would effectively be less robust in patients than in controls. If it takes patients longer to process the stimulus itself, then giving them longer stimulus durations than controls might be necessary to create the same input for subsequent processing. This would be important because it would suggest that slowed early information processing during everyday life may be a factor limiting effective mobilization of executive and regulatory processes. To test this, we used a pain-empathy paradigm that reliably produces attention-sensitive late wave (350-900ms) positivity differences between pain and neutral stimuli (Corbera et al., 2014; Fan and Han, 2008; Han et al., 2008). We have found that in healthy controls some top down regulatory processes, as reflected in the difference in late positive responses to pain vs. neutral stimuli, depend on longer stimulus duration; i.e., they are present with 500ms but not 200ms stimulus presentation (Ikezawa et al., 2013). In the present study, we presented the pain-related stimuli to controls for either 200ms or 500ms, and to patients for 500ms or 800ms. This enabled us to compare patients and controls with the same stimulus duration (500ms), and also compare 500ms and 800ms presentation in patients to 200ms and 500ms presentations respectively in controls.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Healthy Control | Schizophrenia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male = 12 | Female = 6 | Male = 8 | Female = 11 |

| Ethnicity | African American = 7 | White = 11 | African American = 11 | White = 8 |

| Mean | Mean | |||

| Age* | 39.7±2.0 | 46.05±2.1 | ||

| Subject's years of education* | 15.6±0.6 | 13.4±0.5 | ||

| Father's years of education | 13.4±0.6 | 13.1±1.4 | ||

| Chlorpromazine equivalent (mg/day) | N/A | 657.6 | ||

p< .05

Participants were 19 adult outpatients at a community mental health center meeting DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994) for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) (First et al., 1998b) by a licensed clinical psychologist, and 18 healthy controls (HC) screened for psychiatric disorders with the Non-patient SCID (First et al., 1998a) and without history of neurological disease or injury. All participants were right handed, native English speakers with normal or corrected-to-normal vision. All patients were taking medication (Table 1) (Andreasen et al., 2010). Gender, ethnicity and parental education did not differ between groups. Patients had less education and were significantly older, although both groups were primarily middle-aged adults. The Yale HIC approved all procedures; subjects provided written informed consent.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Stimuli and Procedure (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Experimental procedure

Stimuli were pictures of hands in painful or non-painful situations as used in previous studies of healthy subjects (Fan and Han, 2008). The pain-related pictures illustrate accidents such as a hand trapped in a drawer or cut by scissors. Each painful picture was matched with a neutral picture that showed the same situation without accident or injury. Ninety candidate stimuli were rated by eight judges using the Wong-Baker faces scale (0 “No hurt” to 5 “Hurts worst”) (Hockenberry, 2005). Pictures with an average score below 1.25 were considered neutral and ones above 2.50 considered painful. Thirty-four neutral and 34 pain-related pictures were selected; half depicted one hand and half two hands, half were African-American hands and half Caucasian hands. Pictures were presented in the center of a black background on a 15-inch color monitor. Each stimulus was 22.5 x 13.5 cm (width x height), subtending a visual angle of 12.7° x 7.7° at a viewing distance of 100 cm. There were two conditions: 1) participants judged pain versus neutral in painful and neutral pictures (Pain Judgment Condition, PC); 2) participants counted the number of hands in painful or neutral pictures (Counting Hands Condition, CC). Participants responded to each stimulus pressing buttons using their right index and middle fingers. Each condition consisted of 3 blocks of 136 randomized trials in which each of the 68 pictures was presented twice. Each block started with instructions for 5s (i.e. PC or CC). Each trial consisted of a central fixation cross presented for 400ms, black screen for 400ms, and picture duration varying randomly between 500 or 800ms in patients and 200 or 500ms in HC, followed by 1000ms response period.

2.2.2 EEG data recording

EEG was continuously recorded using a Biosemi Activetwo system (Biosemi B.V, Amsterdam, Netherlands) from 32 pin-type active scalp electrodes using the 10-20 system, with two flat-type active external mastoid electrodes and one on the nose. Four electrodes were used to measure electrooculogram. All electrodes were referenced off-line to the algebraically computed average of left and right mastoids.

Data was sampled at 1024 Hz, filtered at band-pass 0.1-40 Hz, and epoched to 200ms pre-stimulus and 900ms post-stimulus. Baseline correction was applied to the 200ms prior to stimulus presentation. Behavioral response time and ERP latency were measured relative to stimulus onset. Trials were rejected if artifacts from eye blinks, eye movements, or muscle potentials exceeded ±100 μV at any electrode site. All subjects had a minimum of 50 accepted responses for each stimulus duration and condition. Rejection rates in the PC were 7.9% in patients and 12.7% in HC and in the CC were 12.4% and 12.0%. Rejection rates were higher with pain stimuli in both groups (Pain stimuli = 12.0%, neutral stimuli = 10.0%; df 1,35; F= 9.895; p= .003). Main effects of group and duration and all interactions were non-significant.

2.2.3 ERP data analysis

To limit false positives and consistent with published literature, statistical analyses were conducted on recordings at midline frontal (Fz), central (Cz), parietal (Pz) and occipital (Oz) electrodes. In order to quantify the late positive responses associated with response to the pain-related stimuli, we subtracted the response to neutral stimuli from the response to pain stimuli in the pain condition during the 350-900ms window (DW). We also examined effects of duration on response to pain and neutral stimuli separately during the PC for P3 (350-550ms), LPP1 (550-700ms) and LPP2 (700-900ms) and to neutral stimuli during the CC.

2.3 Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 19). Box-plot revealed no extreme outliers. ERP DW amplitudes were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) with ‘group’ (HC vs patients) and ‘channel location’ (Fz, Cz, Pz and Oz) as factors with significance for all analyses at 0.05 2-tailed. Response accuracy with 500ms stimulus duration was subjected to ANOVA with group, stimulus (pain or neutral) and condition (PC or CC) as factors. Response accuracy within each group was evaluated with stimulus duration, stimulus and condition as factors. Findings were not changed by using age as a covariate and variance associated with age was not significant. (results are reported without age in the model).

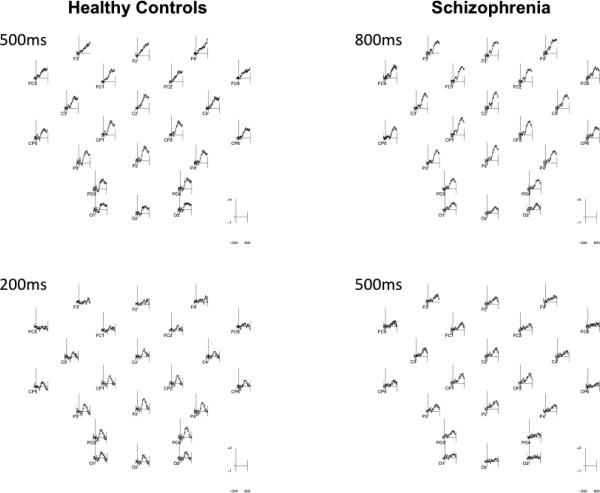

3 Results (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Scalp topographic maps of difference wave [pain - neutral] throughout the 350-900ms time window based on recording from the full array of 32 electrodes

3.1 Stimulus Duration Effects on the Pain Response

Topographic maps of the pain effect difference wave throughout the 350-900ms window (Figure 2) show large differences between patients and controls when both process 500ms stimuli, while the patient response to 800ms stimuli is highly similar to the HC response to 500ms stimuli, and the patient response to 500ms stimuli is highly similar to the HC response to 200ms stimuli. Difference waves for each group for each stimulus duration at multiple locations are presented in Figure 3. Patient wave forms with 500 and 800ms stimuli closely resemble those of HCs with 200 and 500ms stimuli.

Figure 3.

Difference waves reflecting the “pain effect” for patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls at 500 and 200ms stimulus exposure in controls and 800 and 500ms stimulus exposures in patients.

Topographic maps for the pain and neutral stimuli separately (not shown) show other differences between patients and controls. For example, controls show a steady anterior-to-posterior decrease in power while patients show less marked frontal power and prominent posterior power. These group differences are shared, however, by the responses to pain and neutral stimuli, and the difference wave allows the pain effect per se to emerge.

Statistical analyses confirm these impressions. Comparing both groups with 500ms stimulus presentation, the main effects of ‘group’ (df 1,35; F=5.9; p=.02). and ‘channel location’ were significant (df 3,105; F=10.1; p=.000) but the ‘group’ by ‘channel location’ interaction was not (p=.85). When patient response to 800ms stimuli was compared to control response to 500ms stimuli, and when patient response to 500ms stimuli was compared to control response to 200ms stimuli, neither ‘group’ effects (p=.81 and .78) nor ‘group’ by ‘channel location’ interactions (p=.71 and .57) approached significance while main effects of ‘channel location’ remain (p=.000).

The PE DW was greatest in the areas around Cz and Pz. Mean response to both pain-related and neutral stimuli during the PC (i.e., the components of the difference wave) at those sites are affected by stimulus duration in patients and controls in P3, LLP1 and LLP2 components (Table 2). These changes increase the PE DW in patients with 800 as compared to 500ms stimulus duration and in controls with 500 as compared to 200ms stimulus duration. The groups differ with patients showing increases in amplitude of response with longer stimulus durations to pain stimuli in P3 and LLP1 and decrease in LLP2 (800 vs. 500ms; P3 Cz: p=.15 Pz: p=.13, LPP1 Cz: p=.003 Pz: p=.021, LPP2 Cz: p=.003 Pz: p=.004) while the opposite is true of controls (500 vs. 200ms; P3 Cz: p=.27 Pz: p=.60, LPP1 Cz: p=.000 Pz: p=.076, LPP2 Cz: p=.39 Pz: p=.000). Both groups show uniform decreases in amplitude to neutral stimuli with longer durations (Pts 800 vs. 500ms; P3 Cz: p=.18 Pz: p=.77, LPP1 Cz: p=.28 Pz: p=.31, LPP2 Cz: p=.000 Pz: p=.000; HC 500 vs. 200ms; P3 Cz: p=.005 Pz: p=.15, LPP1 Cz: p=.000 Pz: p=.004, LPP2 Cz: p=.018) except for a non-significant increase in controls in the LLP2 at Pz (p=.26). Comparisons between responses to 500 and 800ms pain-related or neutral stimuli in patients, and between responses to 200 and 500ms stimuli in controls are confounded, however, by the fact that stimulus offset waves following 500ms stimuli fall squarely in the 350-900ms response window of interest, while this is not the case with 200 or 800ms stimuli. Cross group comparisons are similarly confounded. We use the DW in our primary analysis in order to subtract out much or all of the influence of the stimulus offset waves.

Table 2.

Amplitudes of P3, LLP1 and LLP2 components for each condition, stimulus duration and stimulus type

| Pts | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | PC | CC | |||||||

| Duration | 500ms | 800ms | 500ms | 800ms | |||||

| Stimlus type | Pain | Neut | Pain | Neut | Pain | Neut | Pain | Neut | |

| P3 | Cz | 2.5±1.0 | 1.7±0.9 | 2.9±1.0 | 1±0.9 | 3.4±1.0 | 3.4±1.0 | 3.8±1.0 | 3.7±1.0 |

| Pz | 4.3±1.2 | 3.3±1.1 | 4.8±1.2 | 3.2±1.2 | 4.6±1.1 | 5.0±1.1 | 5.1±1.1 | 5.3±1.1 | |

| LPP1 | Cz | 3.8±1.0 | 2.3±1.0 | 4.9±1.0 | 1.6±0.9 | 2.9±0.9 | 2.6±0.9 | 3.9±0.9 | 3.6±1.0 |

| Pz | 4.6±1.0 | 3.1±0.9 | 5.6±1.1 | 2.6±1.0 | 3.8±0.8 | 3.9±0.8 | 4.5±0.9 | 4.7±0.9 | |

| LPP2 | Cz | 8.0±0.9 | 6.5±0.9 | 5.5±1.0 | 2.4±0.9 | 5.4±1.2 | 5.5±1.2 | 3.0±1.0 | 2.4±1.0 |

| Pz | 6.7±0.9 | 5.3±0.8 | 4.6±1.0 | 1.8±0.9 | 4.4±0.9 | 4.6±0.9 | 2.2±0.8 | 2.2±0.8 | |

| HCs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | PC | CC | |||||||

| Duration | 200ms | 500ms | 200ms | 500ms | |||||

| Stimlus type | Pain | Neut | Pain | Neut | Pain | Neut | Pain | Neut | |

| P3 | Cz | 2.3±1.1 | 1.2±0.9 | 1.9±1.0 | −0.2±1.0 | 2.7±1.0 | 2.5±1.0 | 1.8±1.0 | 2.2±1.1 |

| Pz | 5.8±1.2 | 4.0±1.1 | 5.6±1.3 | 3.3±1.2 | 5.5±1.1 | 5.6±1.1 | 4.7±1.1 | 5.2±1.1 | |

| LPP1 | Cz | 7.8±1.0 | 6.9±1.0 | 4.5±1.0 | 1.9±0.9 | 7.3±0.9 | 7.1±1.0 | 2.7±0.9 | 2.6±1.0 |

| Pz | 7.2±1.0 | 5.8±1.0 | 6.0±1.1 | 3.3±1.0 | 5.8±0.9 | 5.6±0.8 | 3.1±0.9 | 3.3±1.0 | |

| LPP2 | Cz | 9.4±1.0 | 9.1±0.9 | 10.2±1.1 | 7.8±0.9 | 7.8±1.2 | 7.1±1.3 | 6.5±1.0 | 6.8±1.0 |

| Pz | 5.4±0.9 | 5.2±0.8 | 7.8±1.0 | 5.8±0.9 | 3.7±0.9 | 3.2±0.9 | 4.0±0.8 | 4.1±0.9 | |

3.2 Stimulus Duration Effects on the Simple Cognition Response

In contrast to the group differences in the pain effect, when both patients and controls viewed the neutral stimuli in the counting condition for 500ms the group difference in the overall topographic map did not approach significance (p= .78). In the CC there is little difference in response to pain-related versus neutral stimuli. In both groups, the effects of increasing stimulus duration during the counting condition were similar with pain-related and neutral stimuli, and similar to duration effects with pain stimuli in the pain condition.

3.3 Behavioral

When stimulus duration was the same for patients and healthy controls (500ms), patients were significantly slower and less accurate than healthy subjects: RT patients (764.602 +/− 126.412), controls (669.520 +/− 126.41) (df 1,35; F=5.2; p=.03) and Accuracy patients (.760 +/− .100), controls (.871+/− .102) (df 1,35; F=11.0; p=.002). Response time was slower and accuracy lower for both groups in the PC than CC (RT: df 1,35; F= 104.4; p=.000; Accuracy: df 1,35; F= 51.3; p=.000). The interaction between group and condition was significant for accuracy (df 1,35; F=18.1; p=.000) but not RT (p>.9). Patients were significantly less accurate than controls in the PC (p=.000) but not in the CC (p>.27).

Patients were slower and more accurate with 800 than 500ms stimuli (RT: df 1,18; F=23.0; p=.000; Accuracy: df 1,18; F=11.6; p=.003). The duration by condition interaction was significant for Accuracy (df 1,18; F=11.8; p=.003) but not RT (p>.88). With longer stimulus duration, patient performance increased significantly in the PC but not in the easier CC. Healthy subjects showed similar effects of extending stimulus duration from 200 to 500ms (RT: df 1,17; F=7.6; p=.014; Accuracy: df 1,17; F=21.6; p=.000), although the interaction between duration and condition only approached significance (df 1,17; F=3.5; p=.078).

4 Discussion

Healthy subjects and people with schizophrenia show greater late-wave positivity to pain-related as compared to neutral stimuli when asked to attend to the pain aspects of the stimuli. As we note here and more fully described in Corbera et al. (Corbera et al., 2014), this response is significantly reduced in people with schizophrenia when they and healthy controls are given stimuli of similar duration. Other studies of people with schizophrenia have shown similar abnormalities in attention- and task-sensitive aspects of late wave responses to unpleasant stimuli (Horan et al., 2013; Strauss et al., 2013). These late wave responses are thought to reflect regulatory processes that include attention-mediated effects on responses to affect-evoking stimuli.

We have shown that these late wave responses are significantly greater in healthy subjects with 500ms than with 200ms stimulus presentations, as in Figures 2 and 3, and analyzed more fully in Ikezawa et al. (Ikezawa et al., 2013). This suggests that in healthy individuals engagement of empathy-related self-regulatory processes reflected in late potentials requires longer exposure to the pain-related stimulus. This is consistent with behavioral studies in healthy subjects which report enhanced vigilance and difficulty disengaging attention from threat-related stimuli with 100-200ms stimulus presentations, and attentional avoidance with 500ms stimulus presentations (Onnis et al., 2011). The physiological reasons for needing longer stimulus presentations to engage higher regulatory processes are unclear.

People with schizophrenia process information more slowly than do healthy people. We hypothesized that because of this they may require longer processing time than do healthy controls, and therefore longer stimulus duration in ERP paradigms, to engage cortical processes that depend upon extended lower level processing of evocative stimuli. This hypothesis was confirmed. Late positive ERPs associated with attention modulation of response to seeing pictures of others in pain in patients following 800ms and 500ms stimulus presentations were highly similar to those in healthy controls following 500ms and 200ms stimulus presentations. In contrast, the groups differed significantly when both received 500ms stimuli. Behavioral responses to the stimuli were affected by stimulus duration in both groups.

Our data suggest that slowed processing of sensory input compromises subsequent processing in higher brain centers associated with important cognitive and self-regulatory functions. In this sense, information is literally power – transformation of sensory input into coherent signals from sensory processors to cognitive operators “powers” the cognitive operators. Without adequate input, the cognitive and regulatory aspects of neurocognitive function are compromised. From this perspective, some cognitive deficits in schizophrenia could be seen as secondary to sensory processing deficits. Relative hypofrontality in schizophrenia could in part be secondary to posterior inefficiency. The fact that certain higher and self-regulatory cognitive functions may normally be dependent upon sufficient early processing of relevant stimuli may help explain why measures of slowed information processing account for so much of many other cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Cognitive training or remediation efforts directed at increasing speed of early sensory information processing may benefit people with schizophrenia.

In an attempt to understand the source and nature of the changes in the DW related to stimulus duration, we examined stimulus duration effects on responses to pain and neutral stimuli alone, effects on P3, LLP1 and LLP2 components within the 350-900ms response windows, and effects during a simple hand counting cognition task. The results are potentially informative. Patients showed evidence of higher amplitude P3 and LLP1 responses, and lower amplitude LLP2 responses, with 800 compared to 500ms stimulus durations in the pain condition with pain-related stimuli and in the counting condition with both pain-related and neutral stimuli. In some sense the pain-related stimuli are what are of relevance in the pain condition and the pain-related and neutral stimuli are both of relevance in the counting condition. From this perspective the specific pattern of duration–related effects in patients may provide additional information about the nature of the relationship between early sensory processing and later attention and task-related cognitive operations. Patients also differed from controls in the pattern of stimulus duration effects on P3, LLP1 and LLP2 components, suggesting that the stimulus duration effects in patients reveal aspects of pathology. However, these comparisons within patients between 500 and 800ms stimuli, and between effects of 800 vs 500ms stimuli in patients and 500 and 200ms stimuli in controls, could reflect differing contributions of stimulus offset waves triggered at different time points in relation to stimulus onset. We would expect the stimulus offset effects to be greatest in Oz (where in fact they were visible, see Ikezawa et al. (Ikezawa et al., 2013)), and duration-related effects described above at Cz and Pz were not present at Oz (data not shown). This suggests that stimulus offset effects may not be responsible for the effects of stimulus duration in individual waves, but this possibility must be evaluated in studies with multiple varied stimulus durations (“jittered”). The other way to deal with this potential confound is by using difference waves as we do with our primary analysis and finding.

More work is needed to understand the possible relationship of impaired early sensory processing to the range of cognitive dysfunctions associated behaviorally with slowed information processing in people with schizophrenia. Our observations of normalization of response with longer stimulus exposure is based only on a single, emotion-related probe of late-wave potentials and the frontal regulatory processes with which they are thought to be associated. Effects of increasing stimulus duration on late-wave responses were also noted in both patients and healthy controls in a simple and more purely cognitive task, but these effects were complex and potentially confounded as just described. Another limitation of the present study is that all patients were and had been on medications. Two things, however, make it unlikely that the observations reported are secondary to medication rather than features of illness. First, differences between patients and healthy controls were limited to some comparisons but not others even though medications were present in patients in all comparisons. In fact, the primary analysis was of a difference wave, or within-subject contrast, between two conditions in which the primary effects of medication would likely be the same. Secondly, repeated behavioral studies have demonstrated slowed information processing in un-medicated patients (Knowles et al., 2010; Krieger et al., 2005; Morrens et al., 2007).

In conclusion, when viewing painful stimuli is compared to viewing neutral stimuli, patients required longer presentation of stimuli than did healthy controls to show similar late positive ERP responses associated with directed attention and self-regulation. This suggests that problems that patients have in regulation of emotion responses may be related to slowed processing of the emotion-related stimuli themselves and associated compromise of later stages of cognition including self-regulation. Slowed processing of sensory information in schizophrenia has a complex but potentially important relationship to other neurocognitive deficits. Further systematic study of the effects of stimulus duration on ERP responses is warranted.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to thank Dr Jason Johannesen for his informative comments on the previous version of this article, and would also like to thank the State of Connecticut, Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services through its support for the Connecticut Mental Health Center.

Role of the Funding Source

Supported came from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH084079 to Dr. Wexler) and State of Connecticut Mental Health and Addiction Services through support for the Connecticut Mental Health Center. Sponsors/funders did not participate in design or conduct of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Dr. Wexler designed the study. Dr. Ikezawa performed statistical analyses and literature review. Dr. Corbera conducted ERP sessions and processed ERP data. All authors contributed to and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andreasen NC, Pressler M, Nopoulos P, Miller D, Ho B-C. Antipsychotic dose equivalents and dose-years: a standardized method for comparing exposure to different drugs. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;67(19897178):255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Corbera S, Ikezawa S, Bell MD, Wexler BE. Physiological evidence of a deficit to enhance the empathic response in schizophrenia. European Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.01.005. [epub ahead of schedule article] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Ramsey ME, Gold JM. Overlooking the obvious: a meta-analytic comparison of digit symbol coding tasks and other cognitive measures in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):532–542. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergen M, Marbach S, Brand A, Basar-Eroglu C, Demiralp T. P3 and delta band responses in visual oddball paradigm in schizophrenia. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;440(3):304–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Han S. Temporal dynamic of neural mechanisms involved in empathy for pain: an event-related brain potential study. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(1):160–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Biometrics Research. New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1998a. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. (SCID-I/NP). [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Biometrics Research. New York State Psychiatric Institute.; New York: 1998b. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P). [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Fan Y, Mao L. Gender difference in empathy for pain: an electrophysiological investigation. Brain Res. 2008;1196:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D, Winkelstein ML. Wong's Essentials of Pediatric Nursing. 7th ed. Mosby; St. Louis, Mo.: 2005. p. 1259. [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Hajcak G, Wynn JK, Green MF. Impaired emotion regulation in schizophrenia: evidence from event-related potentials. Psychol. Med. 2013:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikezawa S, Corbera S, Wexler BE. Emotion self-regulation and empathy depend upon longer stimulus exposure. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1093/scan/nst148. [epub ahead of schedule article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles EE, David AS, Reichenberg A. Processing speed deficits in schizophrenia: reexamining the evidence. A. J. Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):828–835. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09070937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger S, Lis S, Janik H, Cetin T, Gallhofer B, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Executive function and cognitive subprocesses in first-episode, drug-naive schizophrenia: an analysis of N-back performance. A. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1206–1208. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR, Kreher DA, Swain A, Goff DC, Holt DJ. Selective emotional processing deficits to social vignettes in schizophrenia: an ERP study. Schizophr. Bull. 2011;37(1):148–163. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrens M, Hulstijn W, Sabbe B. Psychomotor slowing in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33(4):1038–1053. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda N, Pena J, Sanchez P, Elizagarate E, Ezcurra J. Processing speed mediates the relationship between verbal memory, verbal fluency, and functional outcome in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2008;101(1-3):225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.12.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onnis R, Dadds MR, Bryant RA. Is there a mutual relationship between opposite attentional biases underlying anxiety? Emotion. 2011;11(3):582–594. doi: 10.1037/a0022019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Ford JM, White PM, Roth WT. P3 in schizophrenia is affected by stimulus modality, response requirements, medication status, and negative symptoms. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1035–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Sanchez JM, Crespo-Facorro B, Gonzalez-Blanch C, Perez-Iglesias R, Vazquez-Barquero JL. Cognitive dysfunction in first-episode psychosis: the processing speed hypothesis. Br. J. Psychiatry. Suppl. 2007;51:s107–110. doi: 10.1192/bjp.191.51.s107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Kappenman ES, Culbreth AJ, Catalano LT, Lee BG, Gold JM. Emotion regulation abnormalities in schizophrenia: cognitive change strategies fail to decrease the neural response to unpleasant stimuli. Schizophr. Bull. 2013;39(4):872–883. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turetsky BI, Calkins ME, Light GA, Olincy A, Radant AD, Swerdlow NR. Neurophysiological endophenotypes of schizophrenia: the viability of selected candidate measures. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33(1):69–94. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]