Abstract

Objective

Project TEACH provides training, consultation and referral support to build child and adolescent mental health (MH) expertise among primary care providers (PCPs). This study describes how TEACH engages PCP, how program components lead to changes in practice, and how contextual factors influence sustainability.

Method

30 PCPs randomly selected from 139 trained PCPs and 10 PCPs from 143 registered with TEACH but not yet trained completed semi-structured interviews. PCP selection utilized purposeful sampling for region, rurality and specialty. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and analyzed using grounded theory.

Results

PCP participation was facilitated by perceived patient needs, lack of financial and logistic barriers and continuity of PCP-program relationships from training to ongoing consultation. Trained PCPs reported more confidence interacting with families about MH, assessing severity, prescribing medication, and developing treatment plans. They were encouraged by satisfying interactions with MH specialists and positive feedback from families. Barriers included difficulties implementing screening, time constraints, competing demands, guarded expectations for patient outcomes and negative impressions of the MH system overall.

Conclusions

Programs like TEACH can increase PCP confidence in MH care and promote increased MH treatment in primary care and through collaboration with specialists. Sustainability may depend on the PCP practice context and implementation support.

Keywords: child, mental health care delivery, integration, primary care provider training

Introduction

Recognition of the morbidity and premature mortality associated with mental disorders has prompted attempts to increase access to treatment and opportunities for early detection among children [1]. Integration of mental health (MH) with primary care offers the possibility of addressing MH concerns, in conjunction with associated developmental and medical issues, in a setting that is less stigmatized and more accessible to families [2]. Although MH issues commonly present in primary care, primary care providers (PCPs) typically receive limited training in their diagnosis and treatment [3,4]. Most PCPs expand their expertise over the course of their careers through consultation and collaboration with specialists. PCP opportunities for building MH skills through collaboration with MH professionals, however, have typically been more difficult compared to medical sub-specialties because of differences in practice culture, payment for services, information sharing and standards of patient confidentiality [5]. Within the past decade, more than 20 states have introduced programs to overcome these barriers and facilitate collaboration of PCPs and MH professionals serving children and youth (www.nncpcap.org). These programs vary in scope from state to state, but all include components intended to promote sharing of expertise in general and collaboration in the care of particular patients with MH needs. Programs typically provide PCP ready access to case-by-case consultation, training in basic MH care, and facilitation of MH referrals. Initial evaluations suggest that the programs do, indeed, seem to improve PCPs’ willingness to detect and treat MH problems [6,7].

Despite this promise, it is unclear whether these programs effectively promote sustained integration of MH and primary care services – changes that might be reflected in increased treatment of MH problems in primary care and greater interaction between PCPs and MH providers about patient management [2] -- and, if so, how they do it. To address this question, we conducted a qualitative study of PCPs participating in New York State’s Project TEACH (Training and Education for the Advancement of Children’s Health), one of largest of the state programs promoting PCP-MH integration. Because integration requires changes to PCP behavior and to practice culture [8], we looked to theories that propose models for how individuals initiate and behavior change and how their social context influences the sustainability of change [9,10]. We sought to understand what motivated PCP participation, what components of Project TEACH led to changes in practice, what other factors contributed to implementation of these changes and what was the perceived impact on clinical outcomes. Our ultimate goal was to provide insight into how to most effectively implement this strategy of integrating mental health and primary care.

Methods

Programs and population

Funded by the NY Office of Mental Health, Project TEACH refers to two programs (described below) that have similar aims but differ in scale, structure and service areas. Both offer free training, telephone consultation to PCPs, advice on referrals, and the ability to provide face-to-face evaluations when no other resource is available. In both programs, calls from PCPs are handled by a central number and coverage is provided on a rotating basis.

The older of the two programs, the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Education and Support Program for Primary Care Physician (CAPES), has been active since 2005 and serves a geographically large, mostly rural area covering 17 counties in the northeastern NY. Its training component consists of four 3-hour evening core educational sessions, and in most cases the child adolescent psychiatrist (CAP) providing telephone consultation is the same clinician who provides face-to-face evaluations. Telephone consultations were scheduled from 1–1:30 PM weekdays or as needed to accommodate the PCP. As of 2013, CAPES trained 329 PCPs, including both physicians and nurse practitioners. In 2013, CAPES completed 293 telephone consultations between the PCPs and CAP regarding the clinical care 151 that led to direct child psychiatry evaluations. When the PCP and the CAP decide during a telephone consultation that a direct psychiatric evaluation is indicated due to diagnostic or treatment concerns, the PCP contacts the family to refer them to the CAP for face to face evaluation. There were 318 PCP requests for information about referrals to local MH specialists.

The newer of the two programs, the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for Primary Care program (CAP PC), started in 2010, as a collaboration of five academic medical centers serving the remainder of the state (35 counties), including all of its major metropolitan areas. CAP PC’s training component involves a weekend-long course (the REACH Institute Mini-Fellowship for Assessing and Managing Mental Health Problems in Children and Adolescents) followed by twice monthly case-based phone conferences over a period of 6 months. Since its founding,, CAP PC has trained 400 PCP and registered 1100 PCPs (making them eligible to use the on demand phone line) and completed 1500 telephone consultations on approximately 1200 cases (i.e. some cases had more than one call during the year). Eleven percent of these cases were referred to the CAP for direct psychiatric evaluation, while the rest were managed by the PCP. There were 300 PCP requests for information about referrals to local MH specialists.

Participants in this study were randomly sampled from PCPs registered with Project TEACH as of March, 2011. Ten were selected from among 143 who had not yet taken part in a training activity and 30 from among 139 who had completed training. PCPs who had completed 4 core trainings in CAPES, or a CAP PC weekend training and 6 months of telephone case conferences, were considered trained. Maximum variation purposeful sampling [11] with replacement was used to select PCPs to achieve balance by state region, training status, rural versus urban practice site, and specialty (pediatrics versus family practice). Selected PCPs were first notified by email and then contacted by telephone. They were offered a $100 incentive to participate. If they agreed, they completed an online survey to confirm their training status (trained as defined above or no training for the ‘not yet trained’ PCPs).

Interview protocol

The framework for the interview was based on the Unified Theory of Health Behavior Change [10] and the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation and Sustainment (EPIS) model of evidence-based practice implementation [9]. These models propose, respectively, factors that might predict providers’ willingness to change their behavior (in this case, to engage in a program that promotes MH health care and implement what they have learned), and contextual factors that would support willingness to change and sustain new clinical practices. In the EPIS model, a PCP’s “outer context” includes the service environment (reimbursement for MH, psychotropic prescription formularies), inter-organizational relationships (availability of MH providers, ability to refer), consumer support (MH stigma or awareness) whereas the “inner context” applies to the PCP’s motivation to participate, attitude toward MH treatment and intra-organizational factors (appointment times, office practice design and patient population served).

Questions for both trained and not yet trained PCPs included perceptions of the need for and supply of child MH services, willingness and ability to provide or collaborate in MH health care delivery (Table 1). Questions for trained PCP included: what had motivated them to participate, what aspects of training they found most useful, what factors helped or hindered their ability to use the training in day-to-day patient care, and what impact they perceived on clinical outcomes. PCPs who had not yet trained were asked about barriers to participation. All PCPs were asked to rate their comfort level with prescribing certain classes of psychotropic medications on a scale from 1= not comfortable to 10 =very comfortable. Medication classes include psychostimulants, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics and melatonin (Table 2). A research assistant conducted the interviews by telephone in the summer and fall of 2012. They were recorded, edited to remove identifying information, and then transcribed.

Table 1.

Interview guides for trained and not yet trained primary care providers

Trained

|

Not yet trained

|

Table 2.

Primary care provider (PCP) comfort with prescribing: mean scores for PCP rating their comfort level with prescribing psychotropic medications on a scale from 1= not comfortable to 10 =very comfortable.

| Not yet trained PCP | Trained PCP | |

|---|---|---|

| Psychostimulants (for ADHD) | 7.3 | 9.5 |

| Antidepressants | 4.5 | 8.3 |

| Mood stabilizers | 1.9 | 5.2 |

| Atypical antipsychotics | 1.1 | 4.1 |

| Anxiolytics | 4.0 | 6.2 |

| Melatonin | 7.0 | 9.0 |

Data analysis

Grounded theory analytic methods [12] and a template approach [13] were used to develop coding manuals for the two sets of interviews. First, one of the authors (AG) read all of the transcripts and identified themes that were of most interest to the Project TEACH evaluation. The themes were then grouped within categories drawn from the interview questions. Three coders (LW and two research assistants) then independently coded two transcripts and met to refine category definitions, identify examples corresponding to each code, and merge categories where interview questions had prompted responses with overlapping themes. Second drafts of the codebooks were created and the three coders independently coded two additional transcripts. These were reviewed together page-by-page, finding nearly complete agreement. The two research assistants coded all of the transcripts using TAMS software (http://tamsys.sourceforge.net/). Two of the authors (AG and LW) examined the marked segments within each code category to identify subthemes within the categories and higher-level themes that cut across categories. Finally, numeric responses to questions about respondent comfort with medication prescribing were tabulated and means calculated for each class of medication, stratified by trained versus not yet trained PCPs.

The guidelines for qualitative research review were followed and met [14]. This study received IRB approval from the Bassett Research Institute and the NY Office of Mental Health.

Results

Of PCPs initially selected for interviews, the refusal rate was 5.6% among PCP who had not yet trained and 2% among PCPs who had trained. Within the final sample of 40 PCPs, most (85%) were pediatricians reflecting the specialty distribution of PCPs participating in Project TECAH. The mean age was 50 years, 62% were female, 85% were white, 50% practiced in a group setting and 47% were located in a suburban community. The interviews averaged 23 minutes (range 13–42 minutes) for the trained PCPs and 21 minutes (range 15–26 minutes) for the not yet trained PCPs.

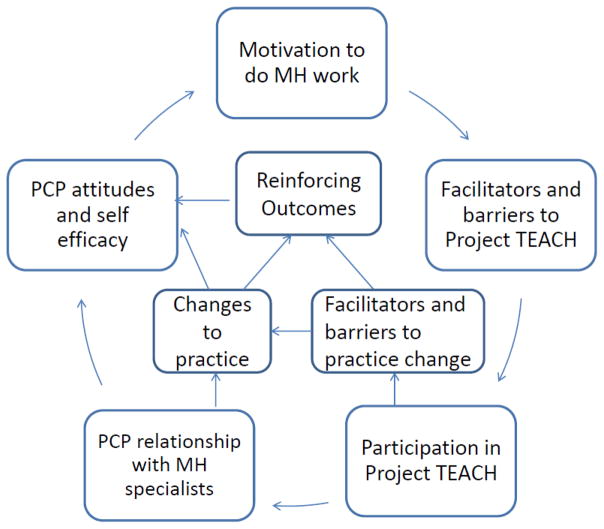

Thematic codes paralleled the interview questions We describe seven themes: motivation for and barriers to Project TEACH participation, training content and structure, changes in PCP attitudes and behavior, barriers to implementing training, factors reinforcing the use of Project TEACH training, changes in PCP’s relationship with MH specialists, and perceived impact on patient outcomes. Representative quotes illustrating these themes are presented in Tables 3–6 and are summarized in the following sections. Figure 1 presents a model summarizing how the themes link to describe influences on program participation and integration implementation.

Table 3.

Representative quotes for PCP motivation to participate in Project TEACH and their experience with training and Project TEACH components.

| Theme | Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| Motivation for training and barriers to participation | I do primary care pediatrics and we have had disappointing mental health resources in our community. So, I and all my colleagues have felt a lot of pressure, you know, to improve the quality of the care that we give related to behavioral health. The main motivation was discomfort with dealing with problems that were among the most common I had to face in an aging pediatric population, meaning lots of teens. And so that was primarily the reason, just that I didn’t feel competent to deal with the things I had to deal with, and I didn’t have adequate options for working with these kids. The main [motivation] was [that] my patients wanted me to do it. Basically, they wanted me to be the one that they talk to, that they confide in. They did not want to go to an outside person. I still feel that that’s kind of outside of the realm of pediatric practice. I don’t think the patient [in this urban area] really wants their pediatrician to deal with anything other than adjustment type issues. I think that if somebody is really feeling threatened they want a therapist… I don’t think they would necessarily want to get drugs from a pediatrician. |

| Training Content and Structure | …the teaching setting and the teacher were excellent. I’m not sure if it would be as effective if it was not Dr. X. … And, pretty much every session he’s given, 90–95% of the pediatricians in the community are there, and there’s almost nothing that can get that many pediatricians in the same room at the same time. They’re {training materials} sitting right by my desk and I refer back to them. I’ve used them for coming up with the proper medication to use in a situation, but usually before I’ve used it I’ve called CAP PC. I haven’t felt comfortable just going and prescribing for somebody. I wanna bounce it off a psychiatrist first. I rely on them {the questionnaires} to provide direction and clues and open up ideas or conversations, but using them, which I didn’t do before has allowed me to be more efficient in getting a hook on some of the problems. The more we do the more comfortable we feel. I would say coming back to not just training but more extensive training. Not just attending one or two lectures here, it’s not that active. But doing, dealing with patients or discussing the cases when we go and attend these sessions. You know it’s a three hour session, it’s not just like one hour. They’re in-depth sessions. I think the monthly conference calls really helped. I would definitely take another half day or a day a year after to really even just go through exactly the same information that we went through. I’m a group learner. I’m an auditory learner and that format works better for me. There is synergy of training, conference calls, and then using the consult line: Then what also changed is my level of confidence that at least my consultation program is there for me to pick up the phone and talk to these people that trained us and did the program and their hotline if I’m in a situation where I cannot find who I need to talk to. |

Table 6.

Representative quotes for changes in PCP relationships with MH specialists and perceived impact of TEACH on patient outcomes.

| Theme | Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| Changes in PCP relationship with MH specialists | A lot of times the [telephone] consultation [with TEACH] will end up with my finding out some new resources and some people available locally to be able to send somebody to for help in managing it -- usually, you know, either a psychologist or a social worker… [and] not having to find a psychiatrist to help with the medication, but for me to be able to work with an ancillary provider. I do feel definitely more confident in co-managing, in making suggestions, in identifying what’s working and what’s not working. And also, looking at side effects in a better way. I personally love the CAP PC {telephone} line, as I said. But I think we need access to better mental health facilities in the city…, And I certainly think many of these patients need more than I can provide. I can certainly be their first stepping stone in prescribing Prozac, but I think they need counseling as well. And it’s remarkably difficult to find counseling for kids in the city. I feel better able to be part of the treatment team in terms of understanding what to expect from a particular medication or therapy approach and that I can help parents feel supported in that. |

| Perceived impact on patient outcomes | …then they get discharged {as psychiatric inpatient}, and they get two weeks worth of medications, but they may not see the psychiatrist for six weeks, and what happens then? They come to see me. I have to refill their meds. I think that’s wrong. I don’t know how they’re doing. And then, guess what? 50% of the time, or better, probably 80% of the time, I don’t get a discharge summary from the {psychiatric} hospital. Without consult service it was frustrating for us, a feeling that we don’t have an access to child psychiatrists and we would have sent them to adult psychiatrist. Or the patient might get worse and end up in the emergency room. Or if they’re a behavioral problem they may end up you know with the conduct problems and may end up somewhere that you don’t want to…caught by the police or accident or in the juvenile facilities because sometimes the ADHD kids or who have other comorbidities might get into trouble with the law too. In the absence of the consult service, I would still be banging my head against the wall along with the parent and the kid. I think that the first week of school he would have gotten kicked out again. …I certainly think many of these patients need more than I can provide, and I can certainly be their first stepping stone in prescribing Prozac, but I think they need counseling as well. And it’s remarkably difficult to find counseling for kids in the city. When you talk about a two or three month delay in seeking care, a lot can happen in the life of a family and the life of a child in that time frame and it was just so awful feeling like there was nothing I could do except say, “Hang on and wait for your appointment.” There is only so much apologizing you can do for the system. |

Figure 1.

Model for the relationship of PCP motivation, attitudes, and facilitators to participation in the program and implementation of sustained integration of MH into primary care.

Motivation for and barriers to participation

One of the primary motives for participating in Project TEACH, identified by both trained and not-yet-trained PCPs, was a perceived increase in MH problems among their patients. Some also described a simultaneous worsening of access to available or acceptable MH resources. PCPs wanted to address their patients’ needs, which they saw as not being filled elsewhere.

Several factors contributed to increasing need. As PCPs got older, so did the patients they typically cared for; consequently there were more adolescent MH problems to manage. Other PCPs had changed practice settings and found themselves working with higher risk populations. Demand from families also contributed to motivation. Some PCPs indicated that their patients’ families preferred to receive MH treatment in primary care. However, other PCPs stated that families would rather receive care from a specialist.

Factors determining signing up for the training centered on convenience and cost (the training sessions and continuing medical education credits were free of charge). However, not all PCPs felt they had time for the off-site trainings that the project offers. Those not yet trained suggested that alternative means of participation or less distance to travel would have been helpful.

Training content and structure

Project TEACH participants liked active training methods (engaging instructors and the use of role plays and patient simulations). Free website access to screening tools, medication guidelines, and patient education materials were seen as increasing efficiency, providing diagnostic direction, and facilitating communication with MH specialists. Overall, the program was seen as an efficient way for mid-career PCPs to stay up to date and gain or regain confidence in managing MH problems. Moreover, it was the sum of the program components – training, reference materials, on-going consultation and referral support that appeared to work synergistically in changing practice among trained PCPs.

The project’s structure also helped develop relationships between PCPs and MH specialists. Having the same CAP involved in training and follow-up consultation facilitated the PCP-CAP relationship, decreased PCP hesitancy to call the consult line and increased credibility of the advice provided by the CAP.

Changes in PCP attitude and behavior

Many trained PCPs suggested that, as a result of participation, they had become more willing to take responsibility for the diagnosis and treatment of MH problems. They attributed this to changes in their attitudes about the inclusion of MH care in pediatric primary care and their own sense of self-efficacy. Perhaps the most notable change in attitude was that MH could be seen as a legitimate part of primary care and another common sub-specialty health problem for which a PCP could reasonably provide care, similar to asthma or diabetes, provided the case was not too complicated.

Trained PCPs talked about feeling greater competence in interviewing, assessing severity, developing a treatment plan and use of medications for MH disorders. Confidence seemed to lead to more actively and systematically assessing patients for MH problems. These assessments ranged from simply more careful listening to the use of screening tools either before or during visits. Changes in participating PCPs behavior could have an impact on their practice overall, shifting the balance of visits toward a higher proportion being devoted to MH. Some trained PCPs felt that they had become resources for their colleagues, and, in some cases, the person in the practice recognized as the ‘specialist’ in child MH.

Confidence in evaluating the urgency of concerns and in the ability to develop a treatment plan were related to willingness to provide treatment in the primary care office, or to ask a patient to return for further evaluation, rather than immediately offering a referral. PCPs were also more confident in their ability to help families who had been referred for MH care but faced a long wait for an open appointment.

Difference between trained and not yet trained PCPs in comfort with medications

Comfort levels with all psychotropic medication classes were higher among the trained PCPs compared to the not yet trained group (Table 2). Both trained and not-yet-trained PCPs were least comfortable with atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilizers and most comfortable with stimulants. However, trained PCPs reported increased confidence in initiating medication, renewing prescriptions initially written by MH providers, and adjusting doses of psychotropic medications. While untrained PCPs would somewhat resentfully bridge psychotropic prescriptions, they would not change them. Trained PCPs reported increased confidence in bridging prescriptions for psychotropic medications and co-managing side effects.

Barriers to implementing Project TEACH training

Having sufficient time in visits to talk about MH problems was frequently cited as a barrier for both trained and not yet trained PCPs. Competing demands from other required office procedures (vaccinations, visit documentation) and priorities (obesity prevention, nutrition counseling, asthma management, etc.) often left little time for the PCPs to address MH systematically.

There were some trained PCPs for whom discomfort and the “fear of doing the wrong thing” persisted or increased after training. Practice settings with low continuity of patient-provider relationships could contribute to this discomfort: PCPs stressed the importance of being able to follow up once they started to get involved with a child’s MH concerns. Some suburban PCPs worried about negative reactions from families not expecting MH to be addressed in primary care or by a nonspecialist.

Untrained PCPs reported that sorting out diagnostic criteria and differentiating co-morbidities was difficult, while trained PCPs reported that the free, concise and simple screening tools increased their efficiency and productivity. However, some PCPs, initially excited about the use of screening tools, were discouraged by problems implementing their use (having the right screener matched to family concerns and completed prior to a visit).

Factors reinforcing the implementation of Project TEACH training

Just as negative feedback from families could discourage PCPs from using TEACH skills, positive feedback was encouraging. Trained PCPs reported that families were more positive about the MH specialists they were referred to through TEACH, and that for the most part families welcomed talking about MH during primary care visits: “Actually, [since the training] it [mental health] actually is now so much a part [of my agenda] that it’s part of the parents’, too. They kind of expect it.”

Changes in PCP relationship with MH specialists

Participation in Project TEACH seemed to have taken some PCPs a step toward working in a more integrated manner with the MH system. Some reported assuming the “prescriber” role as part of a treatment team alongside a non-prescribing MH specialist. Better knowledge of MH treatment, especially non-pharmacologic treatments with which they had not been familiar, enabled trained PCPs to make better use of existing services. Again, this was reinforced by positive feedback from families who used the services.

For other PCPs, participation enabled them to feel more comfortable talking with MH specialists, and thus reduced barriers to collaboration. Increased comfort seemed to come from a heightened sense of being able to contribute intelligently to conversations about diagnosis and treatment, rather than being in a position of unquestioningly accepting the specialist’s treatment plan.

Despite these successes, Project TEACH did not change trained PCP perceptions that the MH system overall was better than they had perceived it prior to training, nor to feel that it was improving over time. Ongoing sources of pessimism were that there remained a lack of resources to help families, and that outside of the project, access to quality MH care seemed to be decreasing.

Perceived impact on patient outcomes

Trained PCPs seemed cautious about the long-term impact of the MH treatment they provided. Sometimes there was a feeling that a bad outcome had been averted – an unnecessary emergency room visit or a long period of not doing well in school. Other PCPs suggested that they had helped families who would otherwise have “slipped through the cracks” or would not have been willing to seek services at all. But there was ongoing pessimism about limited MH resources, support from schools, and the willingness or ability of families to accept the advice that PCPs were offering.

How could Project TEACH be improved?

Trained PCPs suggested that they could still benefit from more advanced training and more in-depth coverage of the diagnostic criteria and management of many MH conditions. Many suggested the addition of refresher sessions or advanced courses offered as half-day sessions, webinars, and regularly scheduled conferences at academic centers. PCP indicated that medication management, particularly poly-pharmacy, required more in-depth training. Persistent uncertainty about diagnosis and treatment was higher for mood and psychotic disorders compared to ADHD. Other requested topics included eating disorders, autism, sensory processing, behavior problems in young children, and coding and payment issues. Some participants were interested in learning more interviewing, cognitive-behavioral, and family therapy techniques. Structural suggestions included increasing the number of training sites and the time frame for when telephone consultation was available.

Discussion

Our analysis of these data suggests a model for the relationship of motivation, attitudes, and facilitators to participation in the program and implementation of sustained integration of MH into primary care (Figure 1). The interview responses suggested that training can alter the attitudes and beliefs of PCPs about MH issues. An “inner context” [9] is represented by PCP motivation (stemming from a perception of demand and need) coupled with low barriers to enrollment (minimal cost, multiple opportunities for participation). Training is case-based and engaging, and it introduces MH specialists who are then positioned to become trusted consultants. Program components work synergistically to scaffold use of newly acquired knowledge through on-demand coaching and to reduce barriers involved with locating clinical materials (reference guides, screening tools, patient handouts) or community resources.

Once new skills are taken up, both the “inner” and “outer” context[9] may reinforce or discourage long-term change in PCP behavior. Reinforcing feedback can come from the positive responses from families, cases with good short-term outcomes, the satisfaction of having known what to do, and from effective interactions with MH colleagues. Because Project TEACH appeared to facilitate linkages between PCPs and skilled, collaborative MH specialists in the community, it allowed new and sustaining clinical relationships to form.

Some aspects of both contexts may also discourage PCP efforts to integrate MH care. Several PCPs expressed that their MH work faced strong competition from other clinical priorities. Other potentially discouraging influences include continued negative perceptions of the larger MH system, continued difficulty engaging families in MH care, and doubt that patients will improve long term. Patient populations may vary in the framing needed to open discussion of MH topics or in their receptivity to receiving MH treatment in the primary care setting. PCPs may also vary in their abilities to work with patients who are initially reluctant to engage in MH care. Some PCPs voiced their frustration trying to implement structural changes such as screening, increasing visit time, or scheduling return visits. Practice structures may be inherently more or less suitable to providing MH care because of the way visits are scheduled, the ease with which new processes such as screening can be implemented, or the extent to which office staff can collaborate or change the way they interact with families.

Several aspects of this model are consistent with observations from other studies of mental health-primary care integration or implementation of changes to primary care practice [15,13]. Active training methods were valued [16], and the provision of ongoing support from trusted consultants appeared to be a core element of success. The way in which Project TEACH-trained PCPs became resources for not yet trained colleagues is consistent with studies of how innovation spreads within organizations [11,17,18]. A study of adult primary care-mental health integration also found increased PCP and clinic staff satisfaction despite ongoing dissatisfaction with the MH system overall [19]. The model also suggests that, at least for some PCPs, programs similar to Project TEACH may need to borrow elements from more intensive practice change interventions if they are to have long-term impact. In particular, the program’s focus on the PCP may need to be supplemented with support for implementing changes in practice context to enable delivery of MH services [20].

Limitations

This is a descriptive study intended to provide direction for future work.

The study sample is composed entirely of PCPs who expressed some interest in MH integration. While some may have held back on actually completing training, the entire sample may represent relatively early adopters. Thus our model of their engagement in the program could differ from what would attract and sustain participation from those who are initially less interested.

Conclusion

Integration of MH services with primary care is central to healthcare reforms underway. We found that participation in a program promoting integration was motivated by PCP perception of patient MH needs and lack of logistic barriers. Initial implementation of integration was facilitated by training that introduced trusted consultants to the primary care community. Ongoing success may be determined in part by the program – ready access to the consultants, provision of needed materials, and linkage to community resources – and in part by the PCP practice context. Programs like Project TEACH have the potential to increase PCP involvement with MH care but sustained change may require assistance altering their practice context, tailoring approaches to particular patient populations, and improving the larger MH system [21].

Table 4.

Representative quotes for changes in PCP attitudes and behavior following participation in Project TEACH.

| Theme | Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| PCP attitudes (comfort and role) | And the program kind of convinced me to look at it more like asthma, you know. I diagnose regular asthma. I treat cases of asthma. If I can’t handle a case that’s incredibly complicated, I refer out. And the program has kind of managed to convince me that ADHD should be looked at in the same way, so partially because I feel more comfortable with the knowledge, but partially just ‘cause it’s kind of re-convinced me of what my role as a primary care doctor is. I think I’m much more comfortable with the medications… discussing the Black Box warning. I’m more comfortable pushing. I have a teenager right now, and then she says she doesn’t want medication, …I feel comfortable pushing for that. I feel more confident starting an initial treatment, following up with the child, adjusting the dosage while I’m waiting for the child to receive mental health evaluation by either a psychiatrist or counseling from a psychologist, because I always try to see if the problem can be helped with behavioral therapy first. But if the child’s problem is so acute that something has to be done in order to keep them functional, I feel, I guess, more able to make that decision and administer the drugs, and then bring them back and monitor the effectiveness. I am less afraid of high dosing of medications than I was and so more willing to push up the dose a little bit. I’m more confident about trying different medications for ADHD, depression and anxiety I feel more confident in my ability to help bridge somebody until they get mental health services.… |

| PCP behaviors with patients and peers | I think the main thing that it [TEACH] did is it got me to incorporate more psychiatric questioning into my routine pediatric work, rather than just waiting for families to raise issues. And that’s an interesting thing because, years ago, I did, and I found that I actually upset people by doing that. And I stopped because I had people who didn’t come back to see me because I would ask those questions, tough questions. But I guess the training and maybe the fact that I’m a little older now has helped me to do that questioning in a way that people aren’t finding invasive. Well, I think what’s changed is that in the past if parents would call about certain things I would be more likely to refer them out somewhere. And since I took the class I’m more willing to see the child myself and, you know, do most of the things on my own, rather than referring … out. More sensitivity to their [mental health problems] presence when it isn’t obvious on the face of it, not taking a simple, ‘I’m fine,’ or checklist ‘no’ to these questions. I would say I’m seeing two to three times as many visits for mental health problems as I used to, and much of that is follow-up. Much of that is continuing to see things myself and follow-up that I would have previously referred and then just assumed it was taken care of. Yeah, one of the practitioners the other day just had a child come in who was kind of off the wall oppositional, and her first thought was, ‘I gotta get this child in to see a psychiatrist.’ I said, ‘Well, it did sound like he needs to see one, but why don’t you do this and that and this. At least we can help him now so no one gets hurt at home.’ I feel much more confident just giving advice.… So it {TEACH} helped me bring the information back and became a conduit to disburse that within my own group, help establish some of the guidelines how to initiate evaluation. So disburse that information to my colleagues in the practice and then being the one in the practice, secondly, who has the largest of the group with mental health conditions in pediatrics. |

Table 5.

Representative quotes for barriers to and reinforcing factors in implementing TEACH training

| Theme | Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| Barriers | ….a questionnaire, under certain circumstances, may save time, but it won’t get you the right answers. So what I do, is I schedule separate visits for mental health discussions. If something comes up at a physical or at a sick visit, or somebody comes in with a complaint that is physical on the phone but I realize is mental health at the time, if we didn’t schedule it for a sufficient period of time, I would generally have them come back with notes and do a careful history to be sure that I get the right diagnosis. …some of the people in the group we’re working in …go to one clinic one day, and another clinic another day, and a third clinic on a third day And so, basically, they can’t see the patients more than once every couple of months… You can’t treat this problem if you’re not going to be able to see that patient weekly for a few weeks so you get them stabilized. From a clinical flow point-of-view, we have a busy practice, you know, it’s often the case that I get into the room, “Oh, you’re here for anxiety.” I look, there’s no anxiety questionnaire completed, so I’m pulling that out, I’m going through it. So, it bogs things down. I’m sure if I was just doing behavioral health, whoever was working with me would know if the main complaint is anxiety, or if that was the referral, they would be getting those forms done. I think part of what’s hard is not feeling like I have enough time to offer more than, “I hear you and I agree with you. These are a concern and here’s one thing to try.” That there’s usually not sufficient time to develop a more comprehensive plan. Then I think well, whew, maybe it’s good that there’s not more time ‘cause I don’t know if I have a depth of suggestions that’s beyond one or two… ..after I did the training and you sort of go home and say we are going to do this and it doesn’t take a couple 2 or 3 months and all of a sudden you know you have a few kids who you’ve done what they’ve said to do and it’s not working which is normal but then you get a little rattled … My biggest conundrum always is not do I feel comfortable using a medication; it’s how sure am I that I have the right diagnosis. If I think I have the right diagnosis, I don’t have any problems with the medications. |

| Reinforcing factors | …the factor that helped me to increase my ability was being able to call the psychiatrist on-call …reinforced what I learned in the training, so just having the availability… I really liked the CAP PC website, which I refer to quite a bit, for information for patients, and again, assessment scales. So much more readily handing out information. I keep some questionnaires ready ahead when the parents come in. One of my nurses does give it before I even go into the room. …the biggest thing has been the insight into how different it is to interview a child about these problems, and the fact that you do need to also interview the parent, and the use of the forms was totally like revolutionary to me. I was like, “Wow. There were forms I can use. That’s so great.” One of the things that really did change for me clinically, and for my colleagues, is that Dr. X {TEACH trainer} pointed out the importance of cognitive behavioral therapy as a proven therapy for kids, especially with anxiety. And so, I went about trying to identify clinicians in our community who would be willing to do it and are trained, and we found a couple. And so, I’ve been sending patients regularly that direction and have been mighty impressed with the positive feedback from the patients, from the parents. |

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: New York State Office of Mental Health, National Institute of Mental Health grant P30MH090322 (Center for Mental Health Implementation and Dissemination Science in States (IDEAS)), and P20MH086048 (Center for Mental Health Services in Pediatric Primary Care).

We appreciate funding from the New York State Office of Mental Health, the National Institute of Mental Health P20MH086048 (Center for Mental Health Services in Pediatric Primary Care) and NIMH grant P30MH090322 (IDEAS Center). We appreciate assistance from Nancy Tallman, Brian Chor, PhD, Stewart Gabel, MD, Matt Perkins, MD, Michele Pollock, LMSW, Joseph Rosczak, MA, Teresa Hargrave, MD and Jade Setias, MS. We acknowledge the following CAP PC training sites: SUNY at Buffalo, University of Rochester in Rochester, SUNY Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, Zucker Hillside Hospital of North Shore Long Island Jewish and Columbia University in NYC.

Abbreviations

- PCP

primary care providers

- CAP

child adolescent psychiatrist

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors, Gadomski, Hoagwood, Wissow, Daly, Kaye, Palinkas have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. Dr. Jeff Daly is project director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Education and Support (CAPES) Program, funded by the NYS OMH. Dr. Kaye is Project Director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for Primary Care (CAP PC) Program, funded by the NYS OMH. Dr. Wissow is associated with BHIPP, the State of Maryland’s program that is similar to Project TEACH.

Conflict of Interest: The authors Gadomski, Hoagwood, Palinkas have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Jeff Daly is project director of CAPES, funded by the NYS OMH. Dr. Kaye is Project Director of CAP PC, funded by the NYS OMH. Dr. Wissow is associated with BHIPP, the State of Maryland’s program that is similar to Project TEACH.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–55. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, Kathol RG, Fu SS, Hagedorn H, Wilt TJ. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 173. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2008. Integration of Mental Health/Substance Abuse and Primary Care. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clatney L, Macdonald H, Shah SM. Mental health care in the primary care setting: family physicians’ perspectives. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(6):884–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health and Task Force on Mental Health. Policy statement--The future of pediatrics: mental health competencies for pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):410–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176–181. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarvet B, Gold J, Bostic JQ, Masek BJ, Prince JB, Jeffers-Terry M, Moore CF, Molbert B, Straus JH. Improving access to mental health care for children: the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1191–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilt RJ, Romaire MA, McDonell MG, Sears JM, Krupski A, Thompson JN, et al. The Partnership Access Line: evaluating a child psychiatry consult program in Washington State. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(2):162–8. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benzer JK, Beehler S, Miller C, Burgess JF, Sullivan JL, Mohr DC, et al. Grounded theory of barriers and facilitators to mandated implementation of mental health care in the primary care setting. Depression Research and Treatment. 2012;2012:11. doi: 10.1155/2012/597157. Article ID 597157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a Conceptual Model of Evidence-Based Practice Implementation in Public Service Sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Dittus P, Collins S. Parent-adolescent communication about sexual intercourse: an analysis of maternal reluctance to communicate. Health Psychol. 2008;27(6):760–9. doi: 10.1037/a0013833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palinkas LA, Holloway IW, Rice E, Fuentes D, Wu Q, Chamberlain P. Social networks and implementation of evidence-based practices in public youth-serving systems: a mixed methods study. Implementation Sci. 2011;6:113. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, McDaniel RR, Stange KC, Jaen CR, Stewart E. Primary care practice transformation is hard work: insights from a 15-year developmental program of research. Med Care. 2011;49:S28–35. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181cad65c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.BioMed Central. [accessed on 9 Jan 2014];Qualitative research review guidelines – RATS. http://www.biomedcentral.com/ifora/rats. RATS guidelines modified for BioMed Central are copyright Clark JP: How to peer review a qualitative manuscript. In Godlee F, Jefferson T (editors). Peer Review in Health Sciences. London: BMJ Books; 2003. p 219–235.

- 15.Gabel S. The integration of mental health into pediatric practice: pediatricians and child and adolescent psychiatrists working together in new models of care. Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;157(5):848–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaaya S, Goldberg D, Gask L. Management of somatic presentations of psychiatric illness in general medical settings: evaluation of a new training course for general practitioners. Med Education. 1992;26:138–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1992.tb00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valente TW. Opinion leader intervention in social networks can change HIV risk behavior in high risk communities. Brit Med J. 2006;333:1082–1083. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39042.435984.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valente TW. Network models and methods for studying the diffusion of innovations. In: Carrington PJ, Scott J, Wasserman S, editors. Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010. pp. 98–116. Van Cleave, J et al, AACAP Poster 1.37, 2012 – need to get full cite from Barry. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vickers KS, Ridgeway JL, Hathaway JC, Egginton JS, Kaderlik AB, Katzelnick DJ. Integration of mental health resources in a primary care setting leads to increased provider satisfaction and patient access. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(5):461–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadeem E, Olin SS, Hill LC, Hoagwood KE, Horwitz SM. Understanding the components of quality improvement collaboratives: a systematic literature review. Milbank Q. 2013;91(2):354–94. doi: 10.1111/milq.12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Improving mental health services in primary care: reducing administrative and financial barriers to access and collaboration. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1248–1251. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]