Abstract

Microfluidic paper-based analytical devices (μPADs) are widely used for performing diagnostic assays. However, in many assays, time-delay valves are required to improve the sensitivity and specificity of the results. Accordingly, this study presents a simple, low-cost method for realizing time-delay valves using a color wax printing process. In the proposed approach, the time-delay effect is controlled through a careful selection of both the color and the saturation of the wax content. The validity of the proposed method is demonstrated by performing nitrite and oxalate assays using both a simple two-dimensional μPAD and a three-dimensional μPAD incorporating a colored wax-printed timer. The experimental results confirm that the flow time can be controlled through an appropriate selection of the color and the wax content. In addition, it is shown that nitrite and oxalate assays can be performed simultaneously on a single device. In general, the results presented in this study show that the proposed μPADs provide a feasible low-cost alternative to conventional methods for performing diagnostic assays.

I. INTRODUCTION

Microfluidic paper-based analytical devices (μPADs) have been used to explore a variety of biological problems of interest and find particular use in the performance of diagnostic assays.1–4 μPADs differ from traditional Lab-on-a-Chip (LoC) technologies in that the fluid is transported by capillary forces rather than a pump. Moreover, μPADs can be fabricated with either hydrophobic or hydrophilic channels using a simple wax printer.5–11 However, in performing biological assays using μPADs, it is essential that both the reaction duration and the intensity of the resulting colorimetric detection signal are carefully controlled so as to improve the sensitivity and specificity of the results.12,13 Consequently, the problem of realizing time-delay valves on μPADs has attracted increasing attention in recent years.14,15

Recently, Lutz et al. proposed a μPAD in which time delays ranging from seconds to hours were achieved by coating the surface with dissolvable sugar.16 The amount of sugar deposited on the paper in channels determined the time delay. Chen et al. presented a method for manipulating two fluids in a sequential manner using a two-terminal fluidic diode fabricated on a single layer of paper.17 They used surfactant to bridge a hydrophobic region to create a diode valve. Li et al. presented a paper-based magnetic valve capable of counting the time and turning the fluidic flow on or off accordingly so as to make possible multi-step analytical tests on paper-based microfluidic devices.18 The valve was actuated by magnetic means. Noh and Philips presented a paper-based fluidic timer composed of paraffin wax, in which the time delay was controlled in the range of 1 min to 2 h by adjusting the amount of paraffin solution deposited on the surface of the paper.12 Multiple layers (5–9) of paper were used in their devices. All of the methods described above provide tools for controlling fluid flow at a specific time. In this work, we further develop a simple technique for controlling the wicking rate in paper-based channels using timers fabricated by printing varying amounts of wax on the channel.

Various researchers have proposed methods for fabricating paper-based microfluidic devices with hydrophobic channels using a simple wax printing process.5,19 In such methods, the wax is first printed on the surface of the paper and is then heated such that it spreads both laterally and vertically. In practice, the vertical spreading of the wax creates hydrophobic barriers which constrain the wicking direction, while the lateral spreading of the wax decreases the sharpness of the channel defined by the barrier and broadens the barrier width. Thus, the wax printing method provides a promising low-cost solution for realizing paper-based microfluidic devices.

Nitrite and oxalate are ubiquitous within the environment and many foods.20 For example, nitrite is commonly used as a meat preservative or as a nutrient in the growing of vegetables. However, excessive levels of nitrite have a detrimental effect on human health since nitrite reacts with the amines in the human stomach to form toxic nitrous amines.21 Similarly, oxalate, a naturally occurring compound in many fruits and vegetables, is easily absorbed into human blood and can lead to a wide variety of medical problems, including kidney stone formation and neurological and cardiovascular disorders.22 Accordingly, effective methods are required for detecting the concentrations of nitrite and oxalate in a timely and accurate manner.

The present study utilizes a color wax printing method to fabricate two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) μPADs for performing simultaneous nitrite and oxalate assays. The time-delays of the two μPADs can be controlled though an appropriate choice of both the wax color and the wax concentration by an image software. The image software can control the wax concentration (gradient) easily through a specification of color gradient function on the printer. The specified wax can be fast printed on a paper for the designed μPADs. The time-delay valves therefore adjust the reaction time in detection zones to obtain the best intensity/quality of each colorimetric assay. The proposed devices provide a promising tool for point-of-care testing (POCT), environmental monitoring, and food safety applications.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Fabrication of fluidic timer

The time-delay channels in the μPADs developed in this study were printed using a commercial wax printer (ColorQube 8570, Xerox, USA) fitted with an original ink cartridge (Color Ink, Xerox, USA). To investigate the effect of the color and saturation of the wax on the time-delay performance, the channels were printed using four different colors, namely, cyan, magenta, yellow, and black, with concentration gradients ranging from 0% to 100%. In preparing the μPADs, the wicking and reaction regions were designed using CorelDraw X5 software (Corel Corporation, Ottawa, Canada) and were printed on Advantec 51A chromatography paper. The printed time-delay channels were melted in an oven at a temperature of 150 °C for 30 s. The penetration depth of the melted wax into the paper was then measured using a Nikon microscope. In addition, the morphology of the wax-printed chromatography paper before and after the heating process was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

B. Principle of colored wax-printed timers

The lateral spreading of colored wax has been examined in the previous studies.19 However, the present study focuses more on the vertical spreading of colored wax and the resulting potential for creating hydrophobic barriers in order to realize time-delay channels for μPAD devices. Rectangles of chromatography paper with dimensions of 7 mm × 3 mm and 7 mm × 9 mm, respectively, were prepared and printed with yellow, cyan, magenta, and black wax, with concentration gradients ranging from 0% to 100% (see Figs. 1(a) and 1(b)). The gradients are controlled by the CorelDraw X5 software which provides users' choices of the gradients. As described above, the mean penetration depth of the wax into the paper (i.e., the mean hydrophobic barrier depth) was measured before and after the heating process using a microscope. As shown in Figs. 1(c)–1(f), the depth of the hydrophobic barrier was found to vary with both the wax color and the wax concentration. Figure 2(a) presents surface SEM images of the printed samples prior to the heating process. Note that the wax saturation is 100% in every case. It is seen that of the four samples, those printed with cyan and yellow wax exhibit a particularly porous-type structure, and therefore provide an improved permeability. Figure 2(b) presents the SEM images of the four samples following the heating process. The results show that the heating process enhances the penetration of the colored wax into the voids surrounding the cellulose fibers of the chromatography paper. In addition, the results confirm that the penetration depths of the cyan and yellow wax are greater than those of the black and magenta wax.

FIG. 1.

(a) and (b) Time-delay channels of different dimensions with wax saturation gradients of 0%–100%; and (c)–(f) penetration depths of yellow, magenta, cyan, and black colored wax given saturations of 100%, 50%, and 20% and heating conditions of 150 °C for 30 s.

FIG. 2.

SEM images showing pore structures of wax-printed paper samples before (a) and after heating (b), respectively. Note that the wax saturation is 100% in every case. The arrows show the pores and holes. (b) has higher resolution and shows less number of pores than (a).

C. Chemicals and reagents

The basic validity of the wax-printed μPAD concept was evaluated by performing the colorimetric detection of nitrite and oxalate samples using simple test strips of wax-printed chromatography paper. The nitrite test was performed using a reaction reagent comprising 50 mM sulfanilamide, 330 mM citric acid, and 10 mM n-(1-napthyl) ethylenediamine, mixed with methanol as a solvent.23 1.3 μl of reagent was dropped on the reaction zone of the testing strip using a pipette. The reagent spread radially under the effects of capillary action to form a circular region with a radius of approximately 3 mm. 60 s was allowed for methanol evaporation and the reagent would smear onto the paper. The following reaction was then performed:

Nitrite testing was performed using the Greiss reaction method.23 That is, the nitrite was combined with aromatic amine (sulfanilamide) to form diazonium compound, which then reacted with n-(1-napthyl) ethylenediamine to produce pink azo dye.

Oxalate testing was also performed using a single-step reaction process. The reaction reagent comprised 20% titanium (III) chloride and pure water, which were mixed to produce 5% titanium (III) chloride. As in the nitrite test, 1.3 μl of reagent was dropped in the reaction zone of the testing strip and allowed to spread to a radius of approximately 3 mm. After a wait of around 20 min to allow for water evaporation, the following reaction process was performed:

This method was used for oxalate testing. In other words, the oxalate combined with the titanium (III) chloride to form yellow titanium oxalate.24,25

In performing the nitrite and oxalate assays, a fluidic timer doped with blue cobalt chloride (CoCl2) was used to indicate the end of the assay.26 Specifically, as the sample fluid passed through the delay-valve of the fluidic timer and entered the reaction zone, the resulting chemical reaction caused the CoCl2 to change to a pink color; indicating the end of the assay. The reaction process between the reagent and the CoCl2 was as follows:

D. Design of 2D μPAD

Figure 3(a) presents a schematic illustration of the 2D μPAD developed in the present study. As shown, the device includes a nitrite reaction zone, an oxalate reaction zone, a central injection zone, three time-delay channels (of which, the nitrite time-delay channel is not wax printed), and an observation/reaction zone (i.e., the fluidic timer). It is seen that the oxalate and timer time-delay channels are printed with a linear color wax gradient. Notably, the entire device can be fabricated in a single process using a simple wax printer.

FIG. 3.

(a) Schematic illustration showing configuration of 2D μPAD and (b) basic components in 3D μPAD.

E. Design of 3D μPAD

Figure 3(b) presents a series of photographs showing the main components in the 3D μPAD proposed in the present study. As shown, the components include a circular piece of filter paper, three test strips (nitrite, oxalate, and fluidic timer), a circular magnet, and an annular aligning ring. The paper components, namely, the central circular filter and the test strips, were cut using a drawing-cutting machine (FC8000, GRAPHTEC, Japan). The central filter paper had a diameter of 8 mm, while the annular aligning ring had an outer diameter of 8 mm and an inner radius of 4 mm. Meanwhile, the test strips each comprised a time-delay channel with a length of 3 mm and a reaction region with a diameter of 6 mm. In assembling the device, the three test strips were simply slotted into pre-cut slits in the central filter paper. The paper components were then clamped between the circular magnet and aligning ring and placed on a base (a petri dish). Notably, the annular ring served not only to ensure a tight connection between the central filter and the test strips but also to define the injection zone of the device.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Figure 4 shows the basic principle of the time-delay channels within the 2D and 3D μPADs. Note that for the 3D device, the wax was printed on the top of the time-delay channel without heating. In both devices, the fluid flows through the wax and paper in a relatively unimpeded manner prior to the heating process due to the inherent porosity of the two media. However, following the heating process, the wax melts and penetrates into the paper. Thus, the number of pores in both media is reduced, and hence a time-delay channel is formed. Figure 5(a) shows the relationship between the porosity and the wax saturation in the unheated and heated conditions, respectively, for each of the considered wax colors (i.e., cyan, magenta, yellow, and black). Note that the results were obtained using a digital analysis technique27 and represent the average values measured over five separate experiments. The porosity was calculated from SEM images by the software ImageJ27 (National Institutes of Health, USA). Basically, the SEM images were digitalized and the areas of pores (or holes) of the SEM images can be counted. The porosity therefore can be computed as the ratio of the area occupied by the pores to that of the paper. The results of the image analysis method proved good agreement with other conventional methods.28 Although only data at the surface can be obtained by the image analysis, the paper thickness (180 μm) is so thin, then the fiber of the paper may be formed in a particular distribution through the paper. Thus, the porosity can be approximately measured by the image processing. The porosity of yellow wax changed the most after heating. From paper chromatography, the stationary phase is the filter paper and the mobile phase is the solvent. During heating process, different colors in mobile phase (liquid wax) have different affinities to the stationary phase (filter paper). The wax attaches to the filter paper by capillary action and diffusion. The separation of components depends on their solubility with the solvent and their affinity to the solvent and filter paper. The most soluble and readily absorbed wax color is the yellow. From Figure 5(a), when the saturation of cyan and yellow color wax is 100%, the porosity changed value is greater than the black and magenta color wax (unheated vs. heated). Referring to Figure 1, the results confirm that the penetration depths of the cyan and yellow wax are greater than those of the black and magenta wax.

FIG. 4.

Schematic illustrations showing fluid flows through (a) 2D μPAD and (b) 3D μPAD before and after wax heating process.

FIG. 5.

(a) Relationship between paper porosity and wax saturation in unheated and heated conditions. (b) Variation of delay time with wax saturation in 2D μPAD (wax heated condition). Note that the data points represent the average values obtained in five separate experiments.

Figure 5(b) shows the variation of the delay time with the colored wax saturation in the 2D μPAD. Note that the results relate to the heated condition. It is observed that for all wax colors, the delay time increases approximately linearly with an increasing wax saturation. In other words, the flow rate within the delay-channel reduces linearly as the wax concentration is increased, i.e., the delay time increases approximately linearly with a decreasing porosity. Note that for a saturation of more than 60%, the flow rate reduces to zero, and hence the corresponding data are not shown in the figure. It was observed that the different saturation of colored wax resulted in different melting diffusion due to the polarity (affinity) of colored wax to the paper. Generally, the paper chromatography exploits differences in solubility and adsorption.29 From Figure 6, we can see that the delayed time is suddenly increased for the case of the 30% to 40% saturation of the yellow colored wax. The sample will flow readily according to how strongly they adsorb onto the stationary phase (colored wax) versus how readily they dissolve in the mobile phase that moves over the stationary phase in chromatography, as a result of different colored wax has different polarity (affinity) of colored wax to the paper. Note that the heated black wax and heated yellow wax have nearly the same value of porosity at 40% saturation in Figure 5(a), but the delayed time is obviously different in Figure 5(b). As mentioned earlier, the solution of the sample will diffuse readily according to how strongly it adsorbs onto the different colored wax.

FIG. 6.

Variation of delay time with wax saturation in 3D μPAD (wax unheated condition). Note that the data points represent the average values obtained in five separate experiments.

Figure 6 shows the variation of the delay time with the wax saturation in the 3D μPAD. It is noted that the results relate to the unheated wax condition. It can be seen that for each wax color, the delay time increases linearly with the wax saturation over the full range of 10%–100%. In general, the results presented in Fig. 5 indicate that the heated wax condition is suitable for the 2D μPAD, while the unheated wax condition is sufficient for the 3D μPAD in Fig. 6.

In performing biological assays using a colorimetric method, the measurement process should be carried out at the point in time at which the visualization signal attains its maximum value. Accordingly, the time-responses of the 2D and 3D μPADs were tested for each of the four considered wax colors and reactants (nitrate and oxalate). In every case, the time response was measured using an external electronic timer. The assays were conducted by applying an aqueous solution of 24 μl to the center of the respective diagnostic device. The intensity of the colorimetric detection signal was then determined by photographing the reaction region of the device and measuring the color intensity using Adobe Photoshop software. Figure 7(a) shows the variation over time of the magenta color intensity given three different nitrate saturations. Figure 7(b) shows the variation over time of the yellow color intensity given three different oxalate saturations. We select the optimal reaction time according to the maximum gap appearing in the intensity and time curves. As shown, the optimal reaction time for the nitrite assay is around 120 s in each case. Similarly, for the oxalate assay, the optimal reaction time is around 30 s. We chose 30 s as the end-point for the assay because the colorimetric signal is nearly at a maximum. However, the 10 s is also nearly at a maximum signal that has yet required more time to complete reaction and diffusion. Likewise, the same reason is for the nitrite assay.

FIG. 7.

(a) Change in mean magenta intensity over time given three different nitrite concentrations. (b) Change in mean yellow intensity over time given three different oxalate concentrations. Note that the results represent the mean values of three separate experiments. Note also that the dotted line indicates the delay time used to generate the calibration curves presented in Figure 8.

Having determined the optimal wax color and reaction time for each reactant, the 2D μPAD device shown in Fig. 3(a) was produced using the wax printer and paper-cutting machine. Note that two of the fingers are used to perform nitrite and oxalate assays, respectively, while the third finger serves as a fluidic timer. For the proposed device, the detection time (Ttotal) required for the sample to pass through the wax-based time-delay channels and react with the corresponding reagents is taken as the time at which the fluidic timer showed pink. As shown in Eq. (1), the total detection time for each assay comprises three components, namely,

| (1) |

Here, Tinjection zone depends on the diameter of the injection zone, Tdelay channel depends on the dimensions of the delay channel and the wax color/saturation, and Tobservation/reaction zone depends on the chemical reaction. In developing the 2D μPAD, the aim was to achieve the same assay time for both reactants (i.e., nitrate and oxalate). Table I summarizes the various time components of Eq. (1) for this ideal design case. As shown in Fig. 7(a), the optimal reaction time for the nitrite assay was 120 s. Thus, to minimize the total assay time, no wax was applied to the corresponding delay-channel (see Fig. 3(a)). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 7(b), the optimal reaction time for oxalate was 30 s. Thus, to achieve a similar total assay time, the corresponding delay channel was printed with 30% magenta wax in order to create a delay time of 90 s (see Fig. 5(b)). As described above, the detection zone of the fluidic timer was using the cobalt chloride (CoCl2) to indicate the end point. Preliminary investigations showed that the reaction time was approximately 20 s. Consequently, the time-delay channel was printed with 40% magenta wax in order to create a delay time of 100 s.

TABLE I.

Decomposition of total assay time for nitrate and oxalate samples in 2D μPAD.

| Tinjection zone (s) | Tdelayed channel (s) | Tobservation/ reaction zone (s) | Ttotal (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrite assay | 1 | 1 | 120 | 122 |

| Oxalate assay | 1 | 90 | 30 | 121 |

| Colored wax-printed timer | 1 | 100 | 20 | 121 |

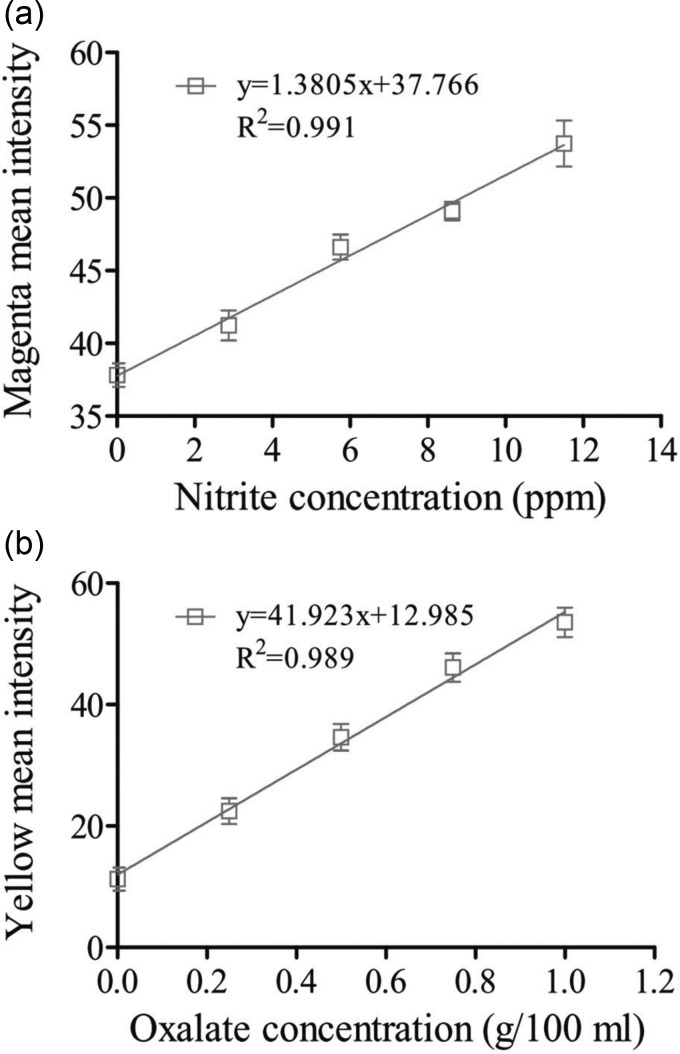

Figures 8(a) and 8(b) show the variations of the mean magenta and yellow color intensities with the nitrite and oxalate sample concentrations, respectively, at a time of 120 s following sample injection. In general, the nitrite level in food should not exceed 10 ppm in order to avoid harmful effects, while the oxalate level should not exceed 50 mg per 100 ml of liquid. The results presented in Fig. 8 show that the proposed 2D device has a linear response for nitrite concentrations of 0–11.5 ppm and oxalate concentrations of 0–1000 mg/100 ml. Consequently, the feasibility of the proposed device for practical nitrite and oxalate assay applications is confirmed.

FIG. 8.

(a) Calibration curve for nitrite 120 s after injection of nitrite sample into 2D μPAD and (b) calibration curve for oxalate 120 s after injection of oxalate sample into 2D μPAD. Note that the results represent the mean values obtained over five separate experiments and the line represents the linear least-squares fit to the experimental data for 2D μPAD.

In developing the 3D μPAD, the aim was again to achieve the same assay time for the nitrate and oxalate reactants. To minimize the total reaction time, the time-delay channel for the nitrite assay was again unwaxed to give a total reaction time of approximately 120 s. As discussed above, the oxalate assay requires a 30-s reaction time. Thus, the corresponding time-delay channel was printed with 60% cyan wax in order to create a delay time of 90 s (see Fig. 6). As in the 2D device, a 20-s reaction time was required for the cobalt chloride. Consequently, the time-delay channel of the fluidic timer was printed with 50% black wax to create a delay time of 100 s.

To ensure the utility of the 3D μPADs to perform the simultaneous assay of nitrite and oxalate, a further series of tests were performed using pure nitrite and oxalate samples and mixed oxalate and nitrite solutions. Figure 9(a) shows the variation of the mean magenta intensity with the nitrite concentration for both the mixed nitrite/oxalate sample and the pure nitrate sample. Figure 9(b) shows the corresponding calibration curves for the mixed oxalate/nitrite sample and pure oxalate sample. It can be seen that in both cases, a good agreement exists between the results obtained for the mixed samples and the pure samples, respectively. In other words, it is inferred that no reaction takes place between the nitrite and oxalate samples. As a consequence, both reactants can be tested simultaneously on the same device.

FIG. 9.

(a) Comparison of calibration curves for mixed nitrite/oxalate solution and pure nitrite solution. (b) Comparison of calibration curves for mixed oxalate/nitrite solution and pure oxalate solution. Note that the results represent the mean values obtained over five separate experiments for 3D μPAD.

IV. CONCLUSION

This study has presented color wax-printed 2D and 3D μPADs for the simultaneous performance of nitrite and oxalate assays. The devices consist principally of an injection zone, a time-delay channel for each reactant, a reaction zone for each reactant, and a fluidic timer. In the proposed devices, the total assay time of the two reactants is controlled through a careful selection of both the wax color applied to the time-delay channels and the wax content. The experimental results have shown that the combined nitrite/oxalate assay can be performed within 120 s on both devices. Moreover, it has been shown that the devices exhibit a linear response over the nitrate and oxalate concentration ranges of interest in safeguarding human health. Thus, the practical feasibility of both devices has been confirmed.

Importantly, both devices are realized using a simple, low-cost fabrication process. The present study has focused on the particular case of nitrite and oxalate assays. However, in practice, the devices can be applied to the simultaneous assays of any biological samples (provided that they do not chemically interact) simply by changing the wax color/saturation of the time-delay channels and choosing appropriate dopants by an image software. Notably, while the 2D device has a more limited application in that it is preprinted and doped in advance (i.e., prior to supply to the end-user), the 3D device has a modular construction and can therefore be tailored by the user to the particular assay requirement by mixing and matching pre-prepared test-strips with the central filter (injection zone). Overall, the results presented in this study confirm that both devices provide a promising solution for diagnosis, food safety, and environmental testing applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided to this study by the Ministry of Science and Technology (Taiwan) under Project Nos. 100-2221-E-006-110-MY2 and 101-2221-E-006-106-MY2.

References

- 1.Li X., Ballerini D. R., and Shen W., Biomicrofluidics 6, 011301 (2012). 10.1063/1.3687398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez A. W., Phillips S. T., Carrilho E., Thomas S. W. III, Sindi H., and Whitesides G. M., Anal. Chem. 80, 3699–3707 (2008). 10.1021/ac800112r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez A. W., Phillips S. T., Whitesides G. M., and Carrilho E., Anal. Chem. 82, 3–10 (2010). 10.1021/ac9013989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katis I. N., Holloway J. A., Madsen J., Faust S. N., Garbis S. D., Smith P. J. S., Voegeli D., Bader D. L., Eason R. W., and Sones C. L., Biomicrofluidics 8, 036502 (2014). 10.1063/1.4878696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrilho E., Martinez A. W., and Whitesides G. M., Anal. Chem. 81, 7091–7095 (2009). 10.1021/ac901071p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu Y., Shi W., Jiang L., Qin J., and Lin B., Electrophoresis 30, 1497–1500 (2009). 10.1002/elps.200800563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lutz B. R., Trinh P., Ball C., Fu E., and Yager P., Lab Chip 11, 4274–4278 (2011). 10.1039/c1lc20758j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez A. W., Phillips S. T., Nie Z., Cheng C.-M., Carrilho E., Wiley B. J., and Whitesides G. M., Lab Chip 10, 2499–2504 (2010). 10.1039/c0lc00021c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu C. K., Huang H. Y., Chen W. R., Nishie W., Ujiie H., Natsuga K., Fan S. T., Wang H. K., Lee J. Y. Y., Tsai W. L., Shimizu H., and Cheng C. M., Anal. Chem. 86, 4605–4610 (2014). 10.1021/ac500835k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sechi D., Greer B., Johnson J., and Hashemi N., Anal. Chem. 85, 10733–10737 (2013). 10.1021/ac4014868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu M. Y., Yang C. Y., Hsu W. H., Lin K. H., Wang C. Y., Shen Y. C., Chen Y. C., Chau S. F., Tsai H. Y., and Cheng C. M., Biomaterials 35, 3729–3735 (2014). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noh H. and Phillips S. T., Anal. Chem. 82, 8071–8078 (2010). 10.1021/ac1005537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noh N. and Phillips S. T., Anal. Chem. 82, 4181–4187 (2010). 10.1021/ac100431y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng C.-M., Martinez A. W., Gong J., Mace C. R., Phillips S. T., Carrilho E., Mirica K. A., and Whitesides G. M., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 49, 4771–4774 (2010). 10.1002/anie.201001005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoumei W., Lei G., Long L., Mei Y., Shenguang G., and Jinghua Y., Biosens. Bioelectron. 50, 262–268 (2013). 10.1016/j.bios.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutz B., Liang T., Fu E., Ramachandran S., Kauffman P., and Yager P., Lab Chip 13, 2840–2847 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc50178g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen H., Cogswell J., Anagnostopoulos C., and Faghri M., Lab Chip 12, 2909–2913 (2012). 10.1039/c2lc20970e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X., Zwanenburg P., and Liu X., Lab Chip 13, 2609–2614 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc00006k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taudte R. V., Beavis A., Wilson-Wilde L., Roux C., Doble P., and Blanes L., Lab Chip 13, 4164–4172 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc50609f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santamaria P., Elia A., Serio F., and Todaro E., J. Sci. Food Agric. 79, 1882–1888 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proksch E., Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 204, 103–110 (2001). 10.1078/1438-4639-00087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liebman M. and Okombo J., J. Food Compos. Anal. 22, 254–256 (2009). 10.1016/j.jfca.2008.10.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Granger D. L., Taintor R. R., Boockvar K. S., and Hibbs J. B., Methods Enzymol. 268, 142–151 (1996). 10.1016/S0076-6879(96)68016-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma S., Nath R., and Thind S. K., Scanning Microsc. 7, 431–441 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decastro M. D. L., J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 6, 1–13 (1988). 10.1016/0731-7085(88)80024-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shakhashiri B. Z., Chemical Demonstrations: A Handbook for Teachers of Chemistry ( The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1983), Vol. 1, pp. 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grove C. and Jerram D. A., Comput. Geosci. 37, 1850–1859 (2011). 10.1016/j.cageo.2011.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allem R. and Uesaka T., in TAPPI Advanced Coating Fundamentals Symposium, Toronto, Canada, 29 April–1 May 1999 (Tappi Press, Atlanta, 1999), pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu X., Minor J. L., and Atalla R. H., Tappi J. 78(6), 175–180 (1995). [Google Scholar]