Abstract

Objective(s):

Helicobacter pylori infection occurs worldwide, but the prevalence of this infection varies greatly among different countries and population groups. The aim of this study was to determine the seroprevalence of anti-Helicobacter pylori and anti-cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) antibodies in asymptomatic healthy population in the center of Iran and to investigate the relation with different parameters.

Materials and Methods:

Totally, 525 individuals aged 17-60 years were enrolled in study. The serum samples of participants were tested for anti-H. pylori IgG and anti-CagA IgG by enzyme-linked immunosorbent method (ELISA). ABO blood grouping was also done by hemagglutination test.

Results:

The seroprevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG was 74.2% and their rates increased with age. The seroprevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG was higher in males (74.6%) than in females (71.6%). There was statistically inverse association between H. pylori infection and education level (P=0.04) and marital status (P=0.000). The most prevalent blood group was type AB with positive Rh-phenotype (82.4%). In H. pylori infected individuals the seroprevalence of anti-CagA antibody was 46.9%. The seroprevalence of anti-CagA IgG was in males 48.6% and in females 31.6%. There was no statistically significant association between anti-CagA IgG positivity and age, occupation, socioeconomic status, ABO blood groups and Rh status.

Conclusion:

These results showed that H. pylori infection was common in the asymptomatic individuals. Almost half of the infected individuals acquire CagA-positive strains of H. pylori. Moreover, it seems that males are more susceptible to infection with CagA-positive strains compared to females.

Keywords: Cytotoxin-assosiated gene A, ELISA, Helicobacter pylori, Iran, Seroprevalence

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is one of the most common bacterial infections in human and has been associated with several gasterointestinal diseases including gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gasteric cancer and gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (1, 2). The prevalence of H. pylori infection varies worldwide. Previous seroepidemiologic studies indicated that about 50% of adults in developed countries and nearly 90% of adults in developing countries were positive for serum antibodies against H. pylori (3, 4). The environmental factors, such as race, socioeconomic and educational status, crowded living conditions and family hygiene levels are associated with H. pylori infection (5, 6). The exact mode of transmission of H. pylori is still unclear, although most of the evidence supports person to person transmission with colonization occurring primarily in childhood. The absence of an environmental reservoir for H. pylori also suggests interpersonal transmission. Fecal-oral and oral-oral routes are likely to be the cause of interpersonal infection by H. pylori (7). The cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) has been identified as a marker of virulence of H. pylori (8). This gene has been detected in half of the H. pylori strains in Western countries and in almost all of the strains isolated in the Asian countries (9, 10). Among diagnostic techniques, serological diagnostic test is now generally accepted as a valid noninvasive screening method for the detection of H. pylori infection (5).The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-H. pylori and its virulence factor CagA in asymptomatic population. In addition, we investigated the correlation between H. pylori infection with age, sex, marital status, occupation, socioeconomic status, ABO blood groups and Rh status.

Materials and methods

Subjects

From August 2011 to December 2011, a cross-sectional seroprevalence study was carried out among healthy subjects in Markazi province in center of Iran. In total, 525 subjects included in the study were 472 males and 53 females aged 17-60 years with a mean of 35.90 years. All subjects were recruited among blood donors of Markazi blood transfusion organization. They were randomly selected according to registration number. All subjects were interviewed by a physician using a questionnaire contained questions about age, sex, marital status, occupation and socioeconomic status. All the participants were basically healthy, with no acute or chronic illnesses. The criteria for enrollment included no history of peptic ulcer disease, no abdominal surgery, no history of therapy for H. pylori infection and no symptoms of upper gastrointestinal disease such as indigestion, nausea, vomiting and epigastria burning pain.

Five ml of venous blood was collected from each participant at the time of interviewing. The blood samples were centrifuged and the sera were separated and immediately stored at -70°C until analysis. ABO blood groups and Rh phenotype evaluations were carried out by standard hemagglutination assays.

Determination of H. pylori specific antibodies in serum

All sera collected for the study were tested for evaluation of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against H. pylori by using the commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Dia Pro, Italy). All positive sera were subsequently tested for anti-CagA IgG antibodies by ELISA method using commercial kits (Dia Pro, Italy). The serum concentration of anti-H. pylori IgG and anti-CagA IgG were expressed in arbitrary units per milliliter (Uarb/ml) as no International standard is available. According to the manufacturer’s guidelines the sensitivity of kit was estimated 98% and the value of 5 Uarb/ml used to discriminate the negative from positive samples.

Statistical analysis

Differences in variables were analyzed using T-test and Chi-square and P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All the available data were analyzed by a computer program (SPSS).

Results

Anti-H. pylori IgG seroprevalence

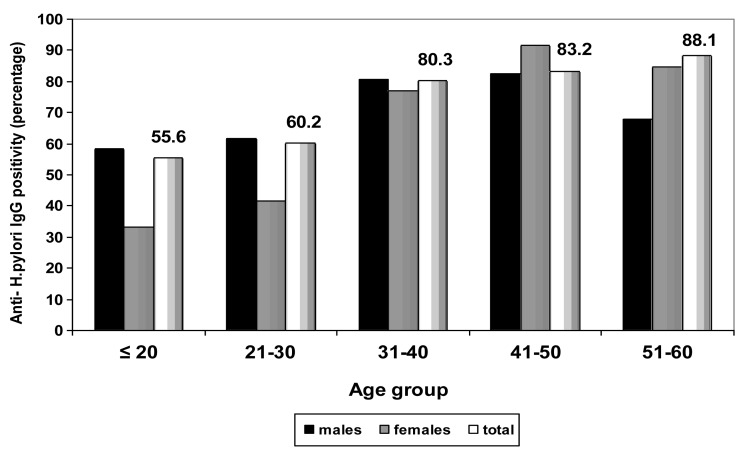

The overall seroprevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG was 74.2% in asymptomatic subjects. As demonstrated in Figure 1 seroprevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG increased with age and subjects ≤ 20 years of age showed 55.6% seroprevalence, while those between 51-60 years of age showed 88.1% seroprevalence. The seropositivity rate was higher in males (74.6%) compared to females (71.6%) but the difference did not reach statistically significant (P=0.650). The prevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG in married subjects (79.8%) was statistically (P=0.000) higher than that observed in single subjects (57.4%) (Table 1). The seroprevalence of H. pylori was higher in subjects with manual occupation (74.5%) than in subjects with nonmanual occupation (74%) but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.486) (Table 1). Comparisons of the rates of anti-H. pylori IgG positivity for different education level groups showed that it was significantly (P=0.04) higher in nongraduates (76.8%) than that observed in college graduates (68.6%) (Table 1). The prevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG was higher in families with >3 family members (75.3%) than in families with <3 family members (69%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.194) (Table 1). The seroprevalence of H. pylori was higher in families with low income (77.8%) than in families with high income (71.5%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.109) (Table 1). The seroprevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG according to ABO blood groups and Rh status are shown in Table 2. The seroprevalence of H. pylori was higher in subjects with blood group AB with positive Rh-phenotype (82.4%) compared to other blood groups, but the differences did not reach statistically significant (P=0.709).

Figure 1.

Seroprevalence of anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG in asymptomatic subjects according to age groups and sex. The seroprevalence of anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG increased with age and seropositivity rate in subjects ≤ 20, 21-30 and 31-40 years of age were higher in males but in subjects 41-50 and 51-60 years of age were higher in female

Table 1.

Relationship of seroprevalence of H. pylori specific antibodies with different parameters

| Parameters | Anti-H. pylori IgG Positivity (%) | Anti-CagA IgG Positivity (%) | P- value1 | P- value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 74/129 (57.4) | 36/74 (46.6) | 0.000 | 0.741 |

| Married | 316/396 (79.8) | 147/316 (46.5) | ||

| Total | 390/525 (74.2) | 183/390 (46.9) | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Manual Occupation | 225/302 (74.5) | 104/225 (46.2) | 0.486 | 0.746 |

| Non Manual Occupation | 165/223 (74) | 79/165 (47.9) | ||

| Total | 390/525 (74.2) | 183/390 (46.9) | ||

| Education Level | ||||

| Non graduates | 281/366 (76.8) | 136/281 (48.4) | 0.04 | 0.349 |

| College graduates | 109/159 (66.6) | 47/109 (43.1) | ||

| Total | 390/525 (74.2) | 183/390 (46.9) | ||

| Numbers of family members | ||||

| <3 | 60/87 (69) | 26/60 (43.3) | 0.194 | 0.545 |

| >3 | 330/438 (75.3) | 157/330 (47.6) | ||

| Total | 390/525 (74.2) | 183/390 (46.9) | ||

| Family income | ||||

| Low income | 182/234 (77.8) | 93/182 (51.1) | 0.109 | 0.122 |

| High income | 208/291 (71.5) | 90/208 (43.3) | ||

| Total | 390/525 (74.2) | 183/390 (46.9) | ||

Represents differences in Seroprevalence of Anti-H. pylori IgG between different statuses in a particular parameter

Represents differences in Seroprevalence of Anti-CagA IgG between different statuses in a particular parameter

Table 2.

Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori specific antibodies in asymptomatic subjects according to ABO blood groups and Rh status

| Blood group | Rh | Anti- Helicobacter pylori IgG positivity (%) | Anti-CagA IgG positivity (%) | P-value1 | P-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| AB | Positive | 28/34 (82.4) | 19/28 (67.9) | 0.376 | 0.482 |

| Negative | 4/6 (66.7) | 2/4 (50) | |||

| Total | 32/40 (80) | 21/32 (65.6) | |||

| B | Positive | 70/103 (68) | 34/70 (48.6) | 0.926 | 0.693 |

| Negative | 9/13(69.2) | 5/9 (55.6) | |||

| Total | 79/116 (68.1) | 39/79 (49.4) | |||

| A | Positive | 105/147 (4.1) | 44/105 (41.9) | 0.339 | 0.946 |

| Negative | 14/17 (82.4) | 6/14 (42.9) | |||

| Total | 119/164 (72.6) | 50/119 (42) | |||

| O | Positive | 145/186 (78%) | 68/145 (46.9) | 0.921 | 0.315 |

| Negative | 15/19 (78.9) | 5/15 (33.3) | |||

| Total | 73/160 (45.6) | ||||

| Total | Positive | 348/470 (74) | 165/348 (47.4) | ||

| Negative | 42/55 (76.4) | 18/42 (42.9) | |||

| Total | 390/525 (74.2) | 180/390 (46.9) | |||

Represents differences in seroprevalence of Anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG between positive Rh and negative Rh in a particular blood group

Represents differences in seroprevalence of Anti-CagA IgG between positive Rh and negative Rh in a particular blood group

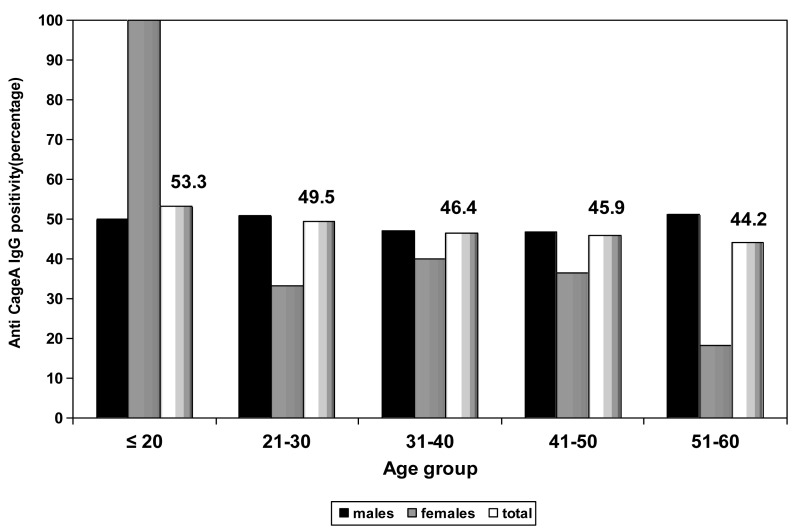

Anti-CagA IgG seroprevalence

The overall seroprevalence of anti-CagA IgG was 46.9%. Comparisons of anti-CagA IgG seropositivity for different age groups showed that ≤ 20 years age group had the highest rate (53.3%) and 51-60 years age group had the lowest rate (44.2%) (Figure 2). The prevalence of serum anti-CagA IgG was statistically (P=0.046) higher in males (48.6%) compared to females (31.6%) (Figure 2). There was no significant difference (P=0.741) between married and single subjects regarding the prevalence of serum anti-CagA IgG, although this parameter was higher in single subjects (48.6%) than that in married subjects (46.5%) (Table 1). No significant difference (P=0.746) were observed between manual occupation (46.2%) and nonmanual occupation (47.9%) regarding anti-CagA antibodies (Table 1). The seropositivity rate in nongraduates (48.4%) was higher than that observed in college graduates (43.1%) but was not statistically significant (P=0.349) (Table 1). The prevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG was higher in families with >3 family members (47.6%) than in families with <3 family members (43.3%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.545) (Table 1). The seroprevalence of H. pylori was higher in families with low income (51.1%) than in families with high income (43.3%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P= 0.122) (Table 1). As demonstrated in Table 2, the seroprevalence of anti-CagA IgG was higher in subjects with blood group AB with positive Rh-phenotype (67.9%) compared to other blood groups but the differences did not reach statistically significant (P=0.576).

Figure 2.

Seroprevalence of Anti-cytotoxin-associated gene A IgG (Anti-CagA IgG) in asymptomatic subjects according to age groups and sex. Comparisons of anti-CagA IgG seropositivity for different age groups showed that ≤ 20 years age group had the highest rate and 51-60 years age group had the lowest rate. The prevalence of serum anti-CagA IgG was higher in males compared to females except for subjects ≤ 20 years of age

Discussion

The prevalence of H. pylori infection varies greatly among countries but higher colonization rates are seen in developing countries compared to developed countries (11). However, studies regarding H. pylori prevalence in different regions of Iran are limited. Our study showed that the overall seroprevalence of H. pylori infection was 74.2% in asymptomatic subjects at 17-60 years. The prevalence of H. pylori infection varies worldwide, so that it has been reported to be 67.5% in south of Iran (12), 41% in Turkey (5), 51% in Saudi-Arabia (13), 31% in Finland (14), 15.4% in Australia (15) and 48% in San-Marino of Italy (16). It is apparent that in developing countries H. pylori infection is more frequently than that in developed countries. The differences in race, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors such as size of family, education level and family income may be the reasons for erratic rates of H. pylori infection reported from different countries (17). In this study, we found correlation between antibodies level against H. pylori in human sera and age of patients that suggests a steady colonization rate through the different age groups and this result is consistent with data from other studies performed in other countries. The results of the current study showed that seroprevalence of anti-CagA IgG was 46.9% among H. pylori infected asymptomatic subjects. In our study, half of the infected subjects were positive for anti-CagA IgG that it is similar to results obtained from the samples collected in Turkey (5). In the current study an reverse correlation was observed between the seroprevalence of anti-CagA IgG antibody with advanced age so that it was 53.3% at age ≤ 20 years and 44.2% at age 51-60 years. Thus, susceptibility to colonization by a CagA-positive strain seems to be linked to age. These observations are difficult to interpret and one possibility would be that at older ages the bacterial colonization may gradually shift from CagA-positive strains to CagA-negative strains, and accordingly, in some adults subjects CagA-positive strains may disappear. Comparisons for sex differences revealed that in our study, prevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG and anti-CagA IgG antibodies were higher in males than females. These data were in accordance with the findings of studies from Iran and Korea (12, 18). Therefore, it seems that the male gender is more susceptible to H. pylori infection and colonization by CagA-positive strains of H. pylori compared to the female. This differential susceptibility may be related to the long-term clinical outcome. This observation may account for higher prevalence of duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer in males. Our results for the first time showed that the prevalence anti-H. pylori IgG was significantly (P=0.000) higher in married subjects compared to single subjects. Moreover, prevalence of anti-CagA IgG was higher in single subjects compared to married subjects, although the difference was not significant. In our study, anti-H. pylori IgG prevalence was associated with occupation and was higher in manual workers in comparison with nonmanual workers. These data give rise to the hypothesis that manual occupation is a particular risk factor for acquisition of infection through closer human contact. The results of the present study showed an inverse relationship between H. pylori infection prevalence and socioeconomic status. In this study, the relationship between prevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG, anti-CagA IgG and socioeconomic factors such size of family, family income and education level were evaluated. Our results showed that prevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG and anti-CagA IgG were higher in nongraduates compared to college graduates. That may correlated to high level of hygiene in college graduates. Our results were in consistent with other finding, reported in Saudi-Arabia (19), so that prevalence of H. pylori infection in college graduates and nongraduates was 54% and 77%, respectively. Another interesting result observed here was that the seroprevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG and anti-CagA IgG enhanced with increasing number of family members and it decreased with increasing of family income. Environmental factors such as crowding in the household have been reported to be linked with H. pylori infection (11, 20-22). Although the exact mode of transmission of H. pylori is not known, but socioeconomic and environmental factors may all contribute toward acquisition of H. pylori infection and low socioeconomic status have been described as risk factors for the acquisition and transmission of H. pylori (23). For many years, individuals with blood group O were found to be more susceptible to duodenal ulcer disease, while gastric ulcer and gastric carcinoma were associated with blood group A (2). Tadege et al demonstrated that although the most prevalent blood group was blood group O, subjects with blood group O don’t show an increased susceptibility to H. pylori infection than those with other blood groups (24). The results of the present study showed an association between blood group AB and positive Rh-phenotype and the prevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG. Our results showed that susceptibility to colonization by H. pylori was lower in subjects with blood group B compared to colonization in subjects with other blood groups. We found that the anti-CagA antibodies were more prevalent in H. pylori-infected subjects with positive Rh-phenotype AB blood group. In fact, the association of CagA-positive strains with blood group AB may partly increase the risk of gastric involvement in H. pylori-infected subjects with this blood group.

Conclusion

The results of present study in healthy Iranian subjects showed that prevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG increased with age and was higher in males compared to females. An inverse correlation was observed between the anti-CagA IgG and older ages. Moreover, the prevalence of anti-CagA IgG was higher in males compared to females. It seems that the males are more susceptible to infection with CagA strains compared to females. It was also found that anti-H. pylori and anti-CagA antibodies were common in subjects with low socioeconomic status. The anti-H. pylori and anti-CagA antibodies were also more prevalent in subjects with blood group AB with positive Rh-phenotype. Accordingly, blood group AB with positive Rh-phenotype may be risk factor for acquiring of CagA-positive H. pylori strain.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Department of Microbiology of Qom Branch of Islamic Azad University, Qom, Iran.

Ethical standards

This study complies with the current laws of Iran. For preparing blood samples from subjects, consenting form completed by them.

References

- 1.Siavoshi F, Malekzadeh R, Daneshmand M, Ashktorab H. Helicobacter pylori endemic and gastric disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2075–2080. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasanzadeh L, Ghaznavi-Rad E, Soufian S, Farjadi V, Abtahi H. Expression and antigenic evaluation of Vac A antigenic fragment of Helicobacter pylori. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2013;16:835–840. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murakami K, Kodama M, Fujioka T. Latest insights into the effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on gastric carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2713–2720. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Megraud F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993;22:73–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apan TZ, Iseri L, Aksoy A, Guliter S. The antibody response to Helicobacter pylori in the sera from a rural population in the central Anatolia region of Turkey. J Health Sci. 2008;54:671–674. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman KJ, Correa P. The transmission of Helicobacter pylori a critical review of the evidence. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:875–887. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.5.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuda R, Morizane T, Tsunematsu S, Kawana I, Tomiyama M. Helicobacter pylori prevalence in dentists in Japan: a seroepidemiological study. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:255–259. doi: 10.1007/s005350200032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu H, Yamaoka Y, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori virulence factors: facts and fantasies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:653–659. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000181711.04529.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nomura AM, Perez-Perez GI, Lee J, Stemmermann G, Blaser MJ. Relation between Helicobacter pylori CagA status and risk of peptic ulcer disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:1054–1059. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Bu XL, Wang QY, Hu PJ, Chen M. Decreasing seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection during 1993-2003 in Guangzhou, southern China. Helicobacter. 2007;12:164–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frenck RW, Jr, Clemens J. Helicobacter in the developing world. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:705–713. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jafarzadeh A, Rezayati MT, Nemati M. Specific serum immunoglobulin G to H. pylori and CagA in healthy children and adults (south-east of Iran) World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3117–3121. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i22.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan MA, Ghazi HO. Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic subjects in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosunen TU, Aroma A, Knekt P, Salomaa A, Rautelin H, Lohi P, et al. Helicobacter pylori antibodies in 1973 and 1994 in the adult population of Vammala, Finland. Epidemiol Infect. 1997;119:29–34. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moujaber T, Macintyre CR, Backhouse J, Gidding H, Quinn H, Gilbert GL. The seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in Australia. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:500–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gatto M, Pretolani S, Bonvicini F, Baldin I, Megraud F, Mayo K, et al. A seroepidemiological survey on the Helicobacter pylori in the general population of the Republic of San Marino: relation with age, social status and lifestyle. J Preven Med Hyg. 2000;41:108–113. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez-Perez GI, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2004;9:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yim JY, Kim N, Choi SH, Kim YS, Cho KR, Kim SS, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in south Korea. Helicobacter. 2007;12:333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Moagel MA, Evans DG, Abdulghani ME, Adam E, Evans DJ, Malaty HM, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter (formerly Campylobacter) pylori infection in Saudi Arabia, and comparison of those with and without upper gasterointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:944–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sathar MA, Simjee AE, Wittenberg DF, Fernandes-Costa FJ, Soni PM, Sharp BL, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Natal/Kwazulu, South Africa. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;6:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katelaris PH, Tippett GH, Norbu P, Lowe DG, Brennan R, Farthing MJ. Dyspepsia, Helicobacter pylori, and peptic ulcer in a randomly selected population in India. Gut. 1992;33:1462–1466. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.11.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rocha GA, Oliveira AMR, Quieroz DM, Moura SB, Mendes EN. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in two different populations from Minas Gerais, Brazil. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1313–1315. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maciorkowska E, Ciesla JM, Kaczmarski M. Helicobacter pylori infection in children and socio-economic factors. Przegl Epidemiol. 2006;60:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tadege T, Mengistu Y, Desta k, Asrat D. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in and its relationship with ABO blood groups. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2005;19:55–59. [Google Scholar]