Abstract

Increasing demand for petroleum has stimulated industry to develop sustainable production of chemicals and biofuels using microbial cell factories. Fatty acids of chain lengths from C6 to C16 are propitious intermediates for the catalytic synthesis of industrial chemicals and diesel-like biofuels. The abundance of genetic information available for Escherichia coli and specifically, fatty acid metabolism in E. coli, supports this bacterium as a promising host for engineering a biocatalyst for the microbial production of fatty acids. Recent successes rooted in different features of systems metabolic engineering in the strain design of high-yielding medium chain fatty acid producing E. coli strains provide an emerging case study of design methods for effective strain design. Classical metabolic engineering and synthetic biology approaches enabled different and distinct design paths towards a high-yielding strain. Here we highlight a rational strain design process in systems biology, an integrated computational and experimental approach for carboxylic acid production, as an alternative method. Additional challenges inherent in achieving an optimal strain for commercialization of medium chain-length fatty acids will likely require a collection of strategies from systems metabolic engineering. Not only will the continued advancement in systems metabolic engineering result in these highly productive strains more quickly, this knowledge will extend more rapidly the carboxylic acid platform to the microbial production of carboxylic acids with alternate chain-lengths and functionalities.

Keywords: fatty acid, Escherichia coli, metabolic engineering, rational strain design, synthetic biology

Introduction

Concerns regarding crude oil depletion and climate change have encouraged the development of renewable biochemicals and biofuels using carbohydrates as the feedstock (Demirbas, 2009; Gabrielle, 2008). Microbial biosynthesis of fatty acids (FAs) for biorenewable chemicals and biofuels has recently garnered extensive attention. Free FAs can be used as precursors for the production of alkanes by catalytic decarboxylation or transesterification (Lennen et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2008; Steen et al., 2010). Alternatively, FAs can be converted biologically to FA ethyl esters, which have high energy density and low water solubility (Steen et al., 2010). Medium chain FAs with 12–18 carbon chain lengths can be effectively used for industrial applications such as detergents, soaps, lubricants, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. FAs can also be catalytically deoxygenated via metal catalysts to produce α-olefins, the building blocks of polymerization.

The genetically suitable Escherichia coli is an excellent host for FA production, given its fully sequenced genome and well-studied FA metabolism. Type II fatty acid biosynthesis (FAB) pathway in E. coli is illustrated in Figure 2a, which is primed with acetyl-CoA and involves reiterative condensation of malonyl acyl carrier protein (ACP) resulting in two-carbon extension of the acyl chain during each elongation cycle. Despite the intrinsic capability of synthesizing FAs for lipid and cell membrane biosynthesis, E. coli does not normally accumulate free FAs as intermediates. FA metabolism is tightly regulated at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels by both the transcription factor and product inhibition, meaning that FA overproduction may require significant re-engineering of cellular metabolism. An excellent overview of FA biosynthesis and its regulation has been reviewed by Handke et al. (2011).

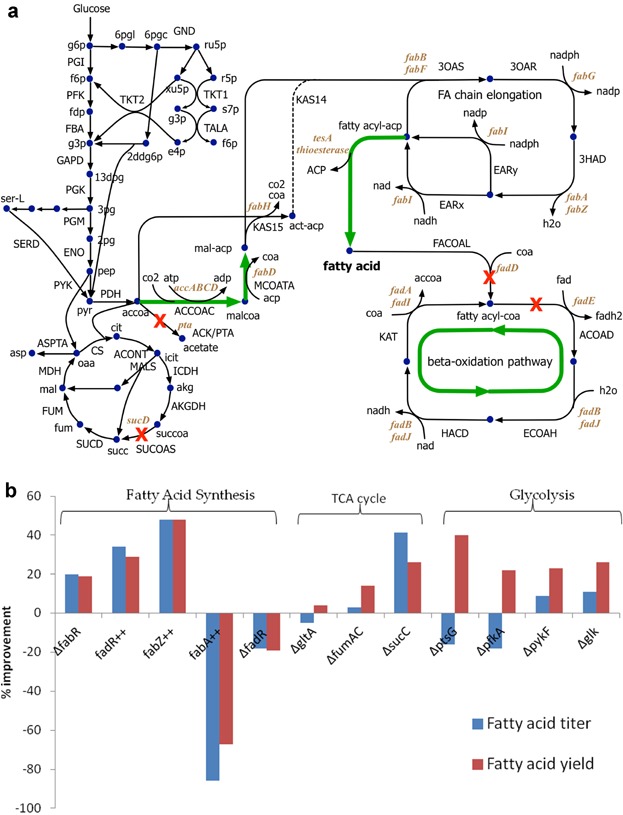

Figure 2.

a: Fatty acid biosynthetic pathways in E. coli utilize a classical metabolic engineering approach to increase fatty acid production. The gene expressions of fabA and fabB in the fatty acid chain elongation are regulated by transcription factor FadR and FabR. Green arrow indicates up-regulation, while red cross indicates deletion. The naming convention for metabolites (lower case) and reactions (upper case) has been imported from iAF1260 model for E. coli (Feist et al., 2007). b: Effect of different genetic modifications on the improvement of fatty acid titer and yield reported by San and Li (2013). All the genetic modifications were carried out in E. coli strain ML103 (ΔfadD). An acyl-ACP thioesterase (pXZ18) was overexpressed in engineered strains to test the effect of the gene knockout (Δ) or overexpression (++). The strains were cultured in LB media with 1.5% glucose and sampled at 48 h. Fatty acid titer and yield improvement were compared with those of the reference strain ML103. Fatty acid titer and yield for the reference strain ML103 are 3.1 g/L and 0.17 g/g.

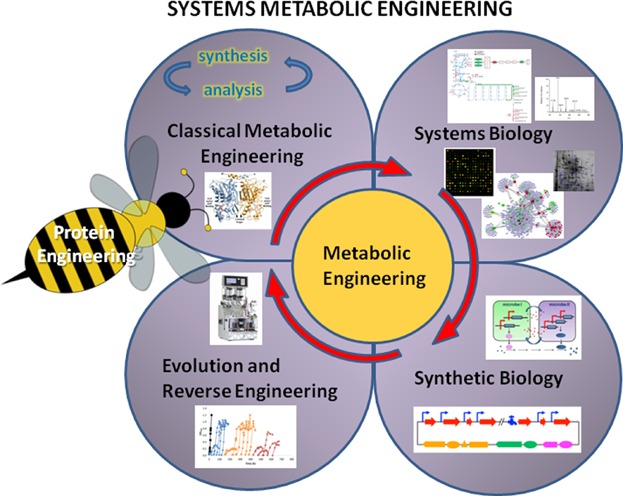

The challenge then, is not only to create a microbial biocatalyst that can produce FAs at high yields, high rates, and high product titers, but also to shorten the development time in the metabolic engineering design cycle, in order to compete effectively with petroleum-based processes. The metabolic engineering design process has evolved into a Systems Metabolic Engineering design process, as shown in Figure 1. Systems Metabolic Engineering, which encompasses systems biology, synthetic biology, and evolutionary engineering at the system level, provides powerful techniques to design new biocatalysts (Lee et al., 2011a). The classical metabolic engineering procedures of constructing and screening strains, based on the collective wisdom of experience, are often complemented with one or more of the new tools to improve and/or fine-tune strain design. The design engineer is faced with a suite of choices in the design process, on whether to use methods in isolation or in combination, although a survey of the literature indicates that at combination of multiple approaches is still not very common to date (Lee et al., 2011a). A plethora of engineering manipulations, although mainly classical metabolic engineering approaches, for free FA production in E. coli exist and have been reviewed in recent years (Huffer et al., 2012; Lennen and Pfleger, 2012; Liu and Khosla, 2010; Zhang et al., 2011a). However, recent successes in construction of high-yielding medium chain fatty acid producing E. coli strains, rooted in different features of systems metabolic engineering, provide an emerging case study of design methods for effective strain design (Dellomonaco et al., 2011; San and Li, 2013; San et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012b).

Figure 1.

Systems metabolic engineering is an integrated field of classical metabolic engineering, system biology, synthetic biology, and evolutionary engineering. The classical metabolic engineering petal exists to construct and screen strains for overproduction. The systems biology petal comprises omics technologies and computational modeling to elucidate the cellular network and generate non-intuitive insight into the biological system. Incorporation of synthetic biology petal creates novel biologically functional parts, modules, and systems using synthetic DNA tools and mathematical methodologies to expand the capacity of the production hosts. Evolution and reverse engineering improves the performance of host strain through adaptive or random evolution under a specified environment. The evolved strain can be reverse-engineered to pinpoint the beneficial mutations and further optimized by metabolic engineering cycle. Nonetheless, protein engineering, shown as a bee, acts as a catalyst to system metabolic engineering by enhancing substrate specificity and productivity of key enzymes in the production pathway. Integrations of the above discipline will increase the efficiency of metabolic engineering in strain development.

In this review, we focus mainly on the recent reports regarding medium-chain FA production in E. coli using different systems metabolic engineering approaches outside the scope of traditional metabolic engineering. In particular, we describe a classical metabolic engineering technique, an integrated experimental and computational strategy, and a synthetic engineering effort for enhancing fatty acid production in E. coli.

Classical Metabolic Engineering

Classical metabolic engineering involves an iterative process of synthesis and analysis, where increasingly refined strains are designed and constructed based on the past knowledge. Based on literature evidence and intuitive guesses, several strategies have been employed to improve FA production, as have been elucidated in Figure 2a. The adopted strategies (Table I) include up-regulating the availability of precursors malonyl-CoA (Lee et al., 2011b; Lennen et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2008) and malonyl-ACP (Lee et al., 2011b; Zhang et al., 2012c) and elimination of the β-oxidation pathway genes fadD or fadE (Lennen et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2008; Steen et al., 2010) to prevent degradation of FAs. Inhibition of re-absorption of extracellular FAs by deletion of fadL has been conducted to improve FA production (Liu et al., 2012). Overexpression of the chain-elongation genes fabA, fabZ, and fabG encoding for the FAB pathway have also been performed (Yu et al., 2011). In addition, acyl-ACP thioesterase, catalyzing the terminal reaction to produce free FAs, is crucial in controlling metabolic flux towards FA. The diversity and specificity of thioesterases have been examined and classified based on their activities and characteristics (Jing et al., 2011). Overexpression of native E. coli thioesterases tesA and tesB (Choi and Lee, 2013; Lennen et al., 2010; Steen et al., 2010), as well as heterologous thioesterases from C. camphorum (Liu et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2008), U. californica (Choi and Lee, 2013; Lennen et al., 2010), R. communis (Li et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2011b), J. curcus (Zhang et al., 2011b), S. pyogenes (Lee et al., ,), and A. baylyi (Zheng et al., 2012) has been identified to overproduce FAs with tailored carbon chain length. Optimal expression of plant thioesterases in E. coli guided by predictions of the ribosomal binding sites (Zhang et al., 2011b) as well as discoveries of new thioesterases, such as a recently identified E. coli thioesterase gene, fadM, involved in the β-oxidation pathway (Dellomonaco et al., 2011), was shown to improve medium-chain FA production. More recently, Torella et al. (2013) developed metabolically engineered E. coli strains with specific carbon chain length FA production by a combined strategy involving the selection of thioesterase, engineering of ketoacyl synthase and redirection of phospholipid synthesis flux. Removal of a competitive pathway towards acetate, however, did not increase the flux towards middle chain FA (Li et al., 2012). The synergy of the aforementioned positive interventions is often used to significantly boost FA production. For example, Steen et al. (2010) reported ∼1.1 g/L FAs (13% of theoretical yield) by deletion of fadE β-oxidation gene with overexpression of cytosolic tesA thioesterase.

Table I.

Literature summary of fatty acid titer and yield in E. coli

| E. coli | Genotype | Thioesterase | Media | Titer (g/L) | Yield (% w/w) | Tools | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DH1 | ΔfadD | TesA’ | M9 with 2% glucose | 0.7 | 3.5 | CME | Steen et al. (2010) |

| DH1 | ΔfadE | TesA’ | M9 with 2% glucose | 1.1 | 6.0 | CME | Steen et al. (2010) |

| BL21 | ΔfadL | TesA’ | Minimal with 2% glucose | 4.8* | 4.4 | CME | Liu et al. (2012) |

| W3110 | ΔfadD | TesA’ | MR with 1% glucose, 0.3% YE | 0.31 | <3.1 | CME | Choi and Lee (2013) |

| W3110 | ΔfadD | TesB | MR with 1% glucose | 0.18 | <1.8 | CME | Choi and Lee (2013) |

| W3110 | ΔfadD | UcTE | MR with 1% glucose | 0.12 | <1.2 | CME | Choi and Lee (2013) |

| MG1655 | ΔfadD | RcTE | LB with 1.5% glucose | 2.2 | <15 | CME | Zhang et al. (2011b) |

| MG1655 | ΔfadD | JcTE | LB with 1.5% glucose | 2.1 | <15 | CME | Zhang et al. (2011b) |

| BL21 | AbTE | M9 with 0.5% tryptone | 3.6* | <6.1 | CME | Zheng et al. (2012) | |

| MG1655 | ΔfadD | UcTE | LB with 0.4% glycerol | 0.77 | <15 | CME | Lennen et al. (2011) |

| MG1655 | ΔfadD, ACC+ | UcTE | LB with 0.4% glycerol | 0.81 | <16 | CME | Lennen et al. (2010) |

| BL21 | ΔfadD, ACC+ | TesA’ + CcTE | M9 with glycerol | 2.5* | 4.8 | CME | Lu et al. (2008) |

| MG1655 | ΔfadD, FabD+ | RcTE | LB with 1.5% glucose | 1.3 | <16 | CME | Zhang et al. (2012c) |

| MG1655 | ΔfadD, SaFabD+ | RcTE | LB with 1.5% glucose | 1.4 | <16 | CME | Zhang et al. (2012c) |

| MG1655 | ΔfadD, ScFabD+ | RcTE | LB with 1.5% glucose | 1.4 | <16 | CME | Zhang et al. (2012c) |

| MG1655 | ACC+, FadD+ | LB | 0.25 | N/A | CME | Lee et al. (2011b) | |

| MG1655 | ACC+, FadD+, FadH+ | LB | 0.25 | N/A | CME | Lee et al. (2011b) | |

| MG1655 | PaAccA+, PaFadD+ | SpTE | M9 with 0.5 g/L YE | 0.24 | <2.4 | CME | Lee et al. (2012) |

| MG1655 | SpTECO | Minimal with 1% glucose and 0.5% tryptone | 0.34 | <3.4 | CME | Lee et al. (2013) | |

| MG1655 | ΔfadD, ΔsucC, FabZ+ | RcTE | LB with 1.5% glucose | 5.7 | <38 | CME | San and Li (2013) |

| MG1655** | ΔfadBA, see text | FadM | Minimal with 3% glucose | 7.0** | 28 | CME | Dellomonaco et al. (2011) |

| MG1655 | ΔfadD, ΔsucC | RcTE | M9 with 1.5% glucose | 1.3 | 11 | CEA | Ranganathan et al. (2012) |

| MG1655 | ΔfadD, FabZ+ | RcTE | M9 with 1.5% glucose | 1.7 | 14 | CEA | Ranganathan et al. (2012) |

| MG1655 | AtoB+, FabB+, EgTER+, see text | Minimal with 2% glycerol, 1% tryptone, 0.5% YE | 3.4 | <35 | SB | Clomburg et al. (2012) | |

| MG1655 | FadB+, FadA+, EgTER+, see text | Minimal with 2% glycerol, 1% tryptone, 0.5% YE | 0.3 | <1.5 | SB | Clomburg et al. (2012) | |

| DH1 | ΔfadE | TesA’ | Minimal with 2% glucose | 3.8 | 19 | SB | Zhang et al. (2012a) |

| DH1 | FadR+ | TesA’ | Minimal with 2% glucose | 5.2 | 26 | SB | Zhang et al. (2012b) |

| BL21 | Modular design (see text) | CnFatB2 | MK with 2% glucose, 1% YE | 8.6* | <7.8 | SB | Xu et al. (2013) |

| BL21 | ΔfadD, ACC+ | TesA’ + CcTE | M9 with glycerol | 4.5* | N/A | SB | Liu et al. (2010) |

| BL21 | ΔfadE | TesA’, CcTE | LB | 0.45 | N/A | SB | Yu et al. (2011) |

| BL21 | ΔfadE, FabZ+, fabG+, FabI+ | TesA’, CcTE | LB | 0.65 | N/A | SB | Yu et al. (2011) |

TE, thioesterase; TesA’, cytosolic E. coli TE 1; Cc, Cinnamomum camphorum; Uc, Umbellularia californica; Pa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Sp, Streptococcus pyogenes; Sc, Streptomyces coelicolor; Sa, Streptomyces avermitilis; Rc, Ricinus communis; Jc, Jatropha curcus; Ab, Acinetobacter baylyi; Eg, Euglena gracilis; Cn, Cocos nucifera; superscript CO, codon-optimized; superscript a, extracellular fatty acid; *, fed batch fermentation; **, batch fermentation in bioreactor; LB, Luria Bertani Broth; YE, yeast extract; CME, classical metabolic engineering; CEA, integrated computational-experimental approach; SB, synthetic biology; N/A, not applicable due to lack of information.

In a novel example of a system-wide metabolic engineering approach, the existing biological system was redesigned by an engineered reversal of the β-oxidation pathway in E. coli, leading to a significant increase in the production yield of carboxylic acids (Dellomonaco et al., 2011). The cellular system was reprogrammed by the manipulation of global regulators. As such, mutations in FadR and AtoC regulon were introduced to express β-oxidation pathway enzymes in the absence of FAs. The native crp gene was replaced by a cAMP-independent mutant to alleviate the catabolite repression in the presence of glucose. ArcA gene was deleted to relieve ArcA-mediated repression induced by oxygen availability. In combination with the elimination of the native fermentation, the reversal of FA degradation pathway, and the overexpression of the selected terminal pathway, extracellular C10–C18 FAs were produced at titer of approximately 7.0 g/L in the bioreactor, with mineral salts medium with yield of 0.28 g/g glucose (∼80% theoretical yield). Thus, redesigning the native FA biosynthesis using a CoA-based functional reversal of β-oxidation provided an efficient platform for the production of FAs.

A classical “push and pull” concept was applied to enhance acetyl-CoA availability, minimize acetyl-CoA drains, eliminate competing pathways and overexpress product formation pathways, ultimately led to a strain with approximately 100% maximum theoretical yield for medium chain-length FA production (San and Li, 2013). Overexpression of fabZ encoding β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase increased FA titer and yield by pulling carbon flux toward FA elongation cycle (Fig. 2b). Naturally occurring FA-sensing transcription factors coordinate and regulate the synthesis and degradation of FA at transcription level. Whereby, FabR antagonizes FA synthesis by repressing fabB and fabA FAB genes, and vice versa for the FadR transcription factor. Indirect up-regulation of FA elongation reactions, by deletion of FabR and overexpression of FadR, showed an increase in FA titer and yield. In addition to the terminal FAB pathway, limited focus has also been given on the central carbon metabolism manipulations for augmenting FA production, however, with less success. San and Li (2013) showed that redirection of TCA cycle flux (deletion of sucC, fumAC, and gltA) towards fatty acid production improved middle chain FA production. Furthermore, gene interruption in the glycolytic pathway (glk, ptsG, pfkA, and pykF) also was shown to be strategic genetic manipulation. Overall, the combination of the fabZ over-expression and sucC deletion in a fadD knockout strain boosted the production to 5.7 g/L C14–C16 FAs with yield of 0.38 g/g glucose in rich media (∼100% theoretical yield accounting for only glucose in the rich media). The technology has been translated into industrial collaboration to produce synthetic diesel and lubricants from biomass (PhysOrg, 2013).

Integrated Computational and Experimental Approach

Even though metabolic engineering has taken long strides in manipulating the metabolic network towards the overproduction of a desired chemical, the process is hampered by bottlenecks of time and accuracy. Recent advances made in genome sequencing have accelerated the construction of genome-scale metabolic networks, which in turn have led to the growth of several rationale-based strain optimization protocols (Burgard et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2011; Maia et al., 2012; Pharkya et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2011). Computational strain design protocols consider the complex interconnectivity of cellular metabolism including cofactor balances to identify key metabolic bottlenecks towards the production of a chemical, and predict (often non-intuitive) strategies to overcome them. Integrated with classical metabolic engineering techniques, these procedures have been successfully employed for the overproduction of several chemicals (Alper et al., 2005; Asadollahi et al., 2009; Bro et al., 2006; Park et al., 2007). Specifically, stoichiometric based modeling has been applied successfully to guide the genetic intervention for increasing availability of malonyl-CoA, a key precursor for FAB (Fowler et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2011).

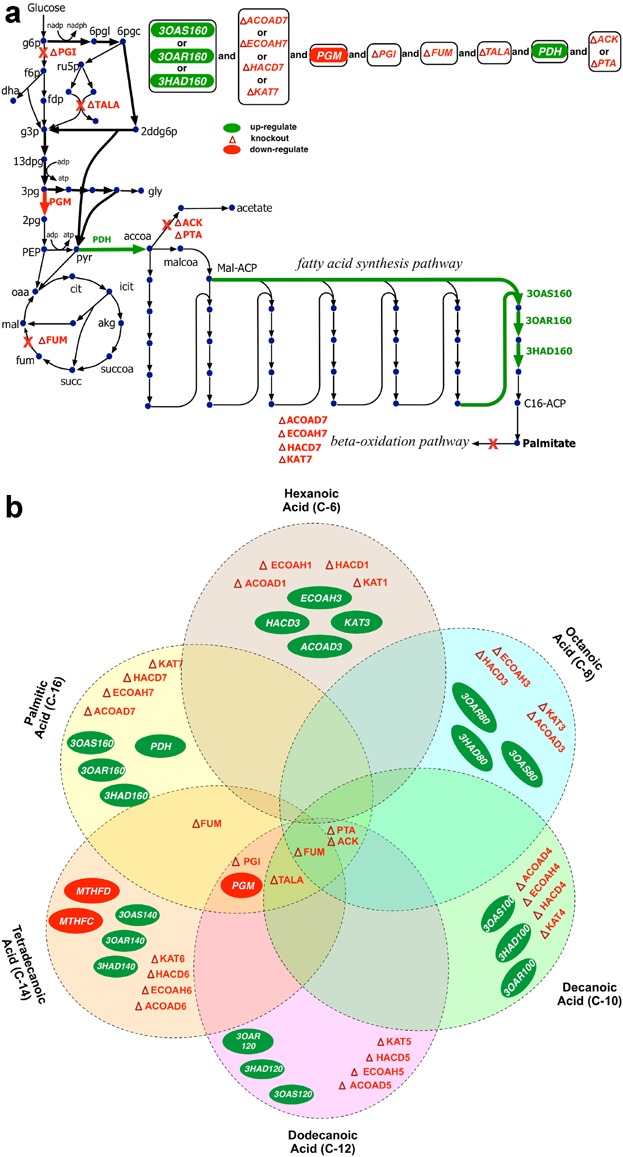

We recently demonstrated the integrated approach of computationally driven predictions and metabolic flux analysis techniques for the overproduction of FAs with different chain lengths (Ranganathan et al., 2012). The OptForce computational protocol (Ranganathan et al., 2010) was used for arriving at suggestions for strain redesign by identifying the minimal set of reactions that need to be actively manipulated to guarantee an imposed production yield. OptForce makes use of in vivo flux measurements to characterize the reference strain and then solves a “worst-case” optimization problem to conservatively identify an exhaustive list of alternate intervention strategies required to meet a pre-specified yield of the desired chemical. It also provides a natural prioritization of results where the most important manipulations are identified first. We observed that the intervention strategies were mostly chain specific that optimized the utilization of the precursors, cofactors and energy equivalents required for the FA synthesis of a particular chain length. For palmitate production, the up-regulation of FA elongation cycle was suggested to pull acetyl-CoA towards FA synthesis, followed by a removal of the β-oxidation pathway to prevent FA degradation. In addition, OptForce identifies several non-intuitive manipulations distal to the terminal FAB pathway that channels metabolic flux towards palmitate (see Fig. 3a). In particular, it suggests re-routing glycolytic flux towards Entner–Doudoroff pathway for the dual objectives of generating reduction cofactor NADPH required in the FA chain elongation and arresting cell growth by reduced production of ATP. In addition, OptForce identified down-regulation of TCA cycle and acetate production pathway as chronologically less prioritized interventions to prevent the drainage of acetyl-CoA away from FA synthesis. In accordance with OptForce prioritized suggestions, a strain with the over-expression of fabZ and acyl-ACP thioesterase (from R. communis), combined with the deletion of fadD, achieved 1.7 g/L and 0.14 g FA/g glucose of C14–16 FA (∼38% theoretical yield) in minimal medium. Interestingly, the prediction of FA biosynthesis up-regulation, TCA cycle interruption, and glycolysis interruption agreed with San and Li (2013), strengthening the robustness of the integrated approach of computational strain design and flux analysis tools. However, contrary to OptForce predictions, some interventions, such as removal of acetate production pathway (through ACK or PTA removal), did not have a significant impact in improving fatty acid yield (Li et al., 2012). The interventions suggested by OptForce are based on the metabolic characterization of the reference phenotype of the strain. As each intervention is implemented, regulatory effects, metabolic toxicity, and other factors beyond the purview of OptForce may increasingly affect the redistribution of metabolic fluxes until causing significant departures between network phenotype predictions and experimental results. Re-deployment of OptForce after short intervals in strain construction, and/or incorporation of substrate-level regulation in the algorithm can result in improving the predictive capabilities of OptForce. Overall, the intervention template suggested by OptForce for the overproduction of FA of individual chain lengths (see Fig. 3b) can be used along with chain-specific thioesterases (Jing et al., 2011) to study the relatively unexplored area of short-chain FA production.

Figure 3.

a: OptForce interventions for the overproduction of palmitic acid in E. coli. b: Venn diagram representing the chain-dependent nature of genetic interventions predicted by OptForce for fatty acids of chain length C6–C16 (Ranganathan et al., 2012). The numbers alongside the fatty acid synthase and β-oxidation reactions refer to the carbon chain-length and cycle number, respectively.

Synthetic Biology

Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control in E. coli tightly regulates FA biosynthesis. Even though several computational procedures exist that integrate transcription and regulatory information with metabolism (Covert et al., 2008; Hyduke et al., 2013), the lack of a detailed mechanistic basis for regulation make these approaches of limited use in metabolic engineering. Synthetic biology plays a crucial role in modeling, understanding, and fine-tuning the core components in metabolic pathways. Engineering core pieces of metabolic pathways helps meet specified performance criteria, such as gaining desired phenotypes, once they are integrated into larger biological systems. Synthetic biology also expands the capacity of host strains to produce heterologous chemicals, and optimizes the synthetic pathway by improving translation efficiency and optimizing biological circuit (Lee et al., 2011a).

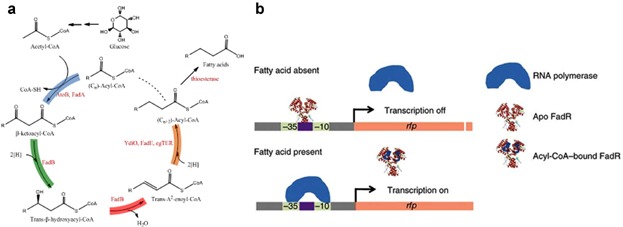

One synthetic biology approach fine-tunes the enzymatic pathways of a specific product, enabling the transfer of optimized systems to another chassis. Clomburg et al. (2012) used a bottom-up strategy to reconstruct a functional reversal of the β-oxidation cycle for production of carboxylic acids through the assembly of well-defined and self-contained enzymes composing the pathway (Fig. 4a). Functional reversal of the β-oxidation cycle comprises of thiolase (AtoB, FadA), 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (FadB), enoyl-CoA hydratase (FadB), and acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (FadE, YdiO, egTER). Each CoA intermediate in the cycle could be converted into carboxylic acids with thioesterase termination pathways. After in vitro kinetic characterization, AtoB, FabB, and egTER were assembled in vivo in E. coli along with the native thioesterase termination pathway, resulting in 3.43 g/L butyrate with 0.35 g/g glycerol yield (∼74% theoretical yield). In vitro kinetic analysis revealed the capability of FadA thiolase on longer chain acyl-CoA. For the synthesis of longer chain carboxylic acids, functional reversal of the β-oxidation cycle could be operated multiple cycles through the integration of AtoB, FadBA, and egTER into the host strain. The success in resembling self-contained enzyme units in the functional reversal of β-oxidation provides a paradigm for the efficient production of carboxylic acids using synthetic biology techniques.

Figure 4.

The synthetic biology approach encompasses (a) the functional reversal of β-oxidation cycle consisting thiolase (blue) encoded by atoB and fadA, 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (green) encoded by fadB, enoyl-CoA hydratase (red) encoded by fadB, and acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (orange) encoded by ydiO and fadE (Clomburg et al., 2012). The acyl-CoA can be converted to fatty acids using thioesterase. b: Design of fatty acid/acyl-CoA biosensor using FadR transcription factor to regulate fatty acid synthesis (Zhang et al., 2012b). In the absence of fatty acid, FadR binds to the promoter, inhibiting the binding of RNA polymerase and thus repressing the transcription. When fatty acid is present, acyl-CoA is formed and antagonizes the DNA binding of FadR. RNA polymerase can then bind to the promoter and initiates the transcription.

Despite the advent in the genetic engineering, metabolic imbalance with low expression pathway genes becomes the bottleneck in biosynthetic pathways. Extremely high levels of gene expression divert cellular resources to unnecessary cell maintenance, instead of devoting the resource to produce the desired chemical. A dynamic sensor-regulator system (DSRS) was developed to dynamically control the synthesis of FAs and the derived biodiesels in E. coli (Zhang et al., 2012a). A FA/acyl-CoA sensor was engineered based on the FadR protein and its associated regulator. Synthetic FA/acyl-CoA-regulated promoters were designed to increase the limited dynamic ranges of native FadR-regulated promoters. The engineered biosensors responded primarily to acyl-CoA, which served as an indirect FA sensor (Fig. 4b). With the insertion of this biosensor, the FA-producing E. coli strain with tesA expression and fadE deletion produced 3.8 g/L FA (∼56% theoretical yield). Furthermore, the biosensor concept was extended to the over-expression of FadR in the E. coli strain with tesA expression and fadE knockout, enhancing FA titer to 5.2 g/L (73% theoretical yield) in minimal medium (Zhang et al., 2012b). FadR over-expression optimally tuned the expression levels of FA pathway genes for the production of FAs. Thereby, the over-expression of an isolated gene in the FA synthesis pathway (fabA, fabB, and fabF) did not increase FA titer as much as the FadR over-expression.

Synthetic biology enables the systematic investigation of pathway limitations and removes the metabolic bottlenecks that are tightly regulated. The customized expressions of enzymatic reactions could enhance carbon flux toward precursor and the corresponding product. The accumulation or depletion of intermediates could be avoided to prevent loss in cell viability and pathway productivity. Most recently, Koffas and coworkers applied a modular synthetic biology strategy to optimize the transcription of fatty acid metabolic pathway, which consists of the modules of upstream acetyl-CoA formation, intermediary acetyl-CoA activation and fatty acid synthase (Xu et al., 2013). Modular pathway optimization by altering plasmid copy number led to a balance in the supply and consumption of fatty acid intermediates (acetyl-CoA and malonyl-ACP). Moreover, translation efficiency could be improved by customizing the ribosomal binding sites of fatty acid pathway modules, thus enhancing fatty acid production. The combination of these synthetic biology tools yielded 8.6 g/L fatty acids (∼22% theoretical yield) in fed-batch fermentation.

Synthetic biology can also be applied to identify and understand the controlling factors in directing carbon flux to the FA pathway (Liu and Khosla, 2010). A cell-free system was developed to interrogate the regulation and synthesis of FAs in E. coli through manipulation of the substrate, cofactors, allosteric regulators and enzyme level (Liu et al., 2010). The study revealed high dependency of FA synthesis on the intracellular concentration of malonyl-CoA. Malonyl-CoA concentration was required to be increased by 10 fold of its reference value under FA overproduction conditions. The rate of FA synthesis was generally linearly correlated to ACC levels with respect to the selection of target ACC. In a subsequent in vitro FA biosynthesis reconstitution study, fabI and fabZ were determined to enhance FA synthesis in a hyperbolic fashion (Yu et al., 2011). Nonetheless, fabF and fabH inhibited FA synthesis at enzyme concentrations higher than 1 µM. Thus, the optimization of FA biosynthesis genes expression is critical to further improve the strain for FA production.

Conclusion and Future Challenges

Classical metabolic engineering, integrated computational/experimental approach, and synthetic biology have contributed towards the improved production of FAs in E. coli, and could be extended to the development of cell factories for specific chemical production. To further dissect the regulations in FA metabolism, system metabolic engineering can be employed to pinpoint beneficial key components in the complicated genetic circuit for strain optimization. Enzymatic bottlenecks could be accurately identified with the development of detailed kinetic models that include metabolic regulatory networks constrained by system biology findings. He et al. (2014) applied a combination of system biology approaches (i.e., fluxomics and transcriptomics) to gain metabolic insights into cellular metabolism under fatty acid production. It was found the reducing equivalent NADPH and ATP as the potential bottleneck for fatty acid production, guiding the direction for future strain development and process optimization to enhance fatty acid production (He et al., 2014). From the industrial standpoint, fermentation using minimal medium and efficient product separation processes can lower operating costs and potentially be competitive for the production of petroleum-based chemicals. Recently, a medium optimization study showed phosphate limitation in continuous fermentation increased fatty acid yield and biomass-specific productivity compared to carbon-limited cultivation (Youngquist et al., 2013). It has also been noted that endogenous FA production reduced cell viability due to the loss of inner membrane integrity (Lennen et al., 2011). Secretion of endogenous FAs could possibly assuage the toxicity effect while reducing product extraction costs. Further investigation is warranted to address the challenges for promising commercialization.

References

- Alper H, Jin YS, Moxley JF, Stephanopoulos G. Identifying gene targets for the metabolic engineering of lycopene biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2005;7(3):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadollahi MA, Maury J, Patil KR, Schalk M, Clark A, Nielsen J. Enhancing sesquiterpene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through in silico driven metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 2009;11(6):328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bro C, Regenberg B, Forster J, Nielsen J. In silico aided metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for improved bioethanol production. Metab Eng. 2006;8(2):102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard AP, Pharkya P, Maranas CD. Optknock: A bilevel programming framework for identifying gene knockout strategies for microbial strain optimization. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;84(6):647–657. doi: 10.1002/bit.10803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YJ, Lee SY. Microbial production of short-chain alkanes. Nature. 2013;502(7472):571–574. doi: 10.1038/nature12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clomburg JM, Vick JE, Blankschien MD, Rodriguez-Moya M, Gonzalez R. A synthetic biology approach to engineer a functional reversal of the beta-oxidation cycle. ACS Synth Biol. 2012;1(11):541–554. doi: 10.1021/sb3000782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covert MW, Xiao N, Chen TJ, Karr JR. Integrating metabolic, transcriptional regulatory and signal transduction models in Escherichia coli. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(18):2044–2050. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellomonaco C, Clomburg JM, Miller EN, Gonzalez R. Engineered reversal of the beta-oxidation cycle for the synthesis of fuels and chemicals. Nature. 2011;476(7360):355–359. doi: 10.1038/nature10333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirbas A. Political, economic and environmental impacts of biofuels: A review. Appl Energ. 2009;86:S108–S117. [Google Scholar]

- Feist AM, Henry CS, Reed JL, Krummenacker M, Joyce AR, Karp PD, Broadbelt LJ, Hatzimanikatis V, Palsson BO. A genome-scale metabolic reconstruction for Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 that accounts for 1260 ORFs and thermodynamic information. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:121. doi: 10.1038/msb4100155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler ZL, Gikandi WW, Koffas MA. Increased malonyl coenzyme A biosynthesis by tuning the Escherichia coli metabolic network and its application to flavanone production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(18):5831–5839. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00270-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielle B. Significance and limitations of first generation biofuels. J Soc Biol. 2008;202(3):161–165. doi: 10.1051/jbio:2008028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handke P, Lynch SA, Gill RT. Application and engineering of fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli for advanced fuels and chemicals. Metab Eng. 2011;13(1):28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Xiao Y, Gebreselassie N, Zhang F, Antoniewicz MR, Tang YJ, Peng L. Central metabolic responses to the overproduction of fatty acids in Escherichia coli based on 13C-metabolic flux analysis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111(3):575–585. doi: 10.1002/bit.25124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffer S, Roche CM, Blanch HW, Clark DS. Escherichia coli for biofuel production: Bridging the gap from promise to practice. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30(10):538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyduke DR, Lewis NE, Palsson BO. Analysis of omics data with genome-scale models of metabolism. Mol Biosyst. 2013;9(2):167–174. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25453k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing F, Cantu DC, Tvaruzkova J, Chipman JP, Nikolau BJ, Yandeau-Nelson MD, Reilly PJ. Phylogenetic and experimental characterization of an acyl-ACP thioesterase family reveals significant diversity in enzymatic specificity and activity. BMC Biochem. 2011;12:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-12-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Reed JL, Maravelias CT. Large-scale bi-level strain design approaches and mixed-integer programming solution techniques. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e24162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Kim TY, Jang YS, Choi S, Lee SY. Systems metabolic engineering for chemicals and materials. Trends Biotechnol. 2011a;29(8):370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Jeon E, Jung Y, Lee J. Heterologous co-expression of accA, fabD, and thioesterase genes for improving long-chain fatty acid production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012;167(1):24–38. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9644-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Jeon E, Yun HS, Lee J. Improvement of fatty acid biosynthesis by engineered recombinant Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2011b;16(4):706–713. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Park S, Lee J. Improvement of free fatty acid production in Escherichia coli using codon-optimized Streptococcus pyogenes acyl-ACP thioesterase. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2013;36(10):1519–1525. doi: 10.1007/s00449-012-0882-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennen RM, Braden DJ, West RA, Dumesic JA, Pfleger BF. A process for microbial hydrocarbon synthesis: Overproduction of fatty acids in Escherichia coli and catalytic conversion to alkanes. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;106(2):193–202. doi: 10.1002/bit.22660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennen RM, Kruziki MA, Kumar K, Zinkel RA, Burnum KE, Lipton MS, Hoover SW, Ranatunga DR, Wittkopp TM, Marner WD., II Membrane stresses induced by overproduction of free fatty acids in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(22):8114–8128. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05421-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennen RM, Pfleger BF. Engineering Escherichia coli to synthesize free fatty acids. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30(12):659–667. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Zhang X, Agrawal A, San KY. Effect of acetate formation pathway and long chain fatty acid CoA-ligase on the free fatty acid production in E. coli expressing acy-ACP thioesterase from Ricinus communis. Metab Eng. 2012;14(4):380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Yu C, Feng DX, Cheng T, Meng X, Liu W, Zou HB, Xian M. Production of extracellular fatty acid using engineered Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact. 2012:11–54. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Khosla C. Genetic engineering of Escherichia coli for biofuel production. Annu Rev Genet. 2010;44:53–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Vora H, Khosla C. Quantitative analysis and engineering of fatty acid biosynthesis in E. coli. Metab Eng. 2010;12(4):378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Vora H, Khosla C. Overproduction of free fatty acids in E. coli: Iimplications for biodiesel production. Metab Eng. 2008;10(6):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia P, Vilaca P, Rocha I, Pont M, Tomb JF, Rocha M. An integrated computational environment for elementary modes analysis of biochemical networks. Int J Data Min Bioinform. 2012;6(4):382–395. doi: 10.1504/ijdmb.2012.049292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Lee KH, Kim TY, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of L-valine based on transcriptome analysis and in silico gene knockout simulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(19):7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702609104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharkya P, Burgard AP, Maranas CD. OptStrain: A computational framework for redesign of microbial production systems. Genome Res. 2004;14(11):2367–2376. doi: 10.1101/gr.2872004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PhysOrg. 2013. Modified bacteria turn waste into fat for fuel, 2013-02-28.

- Ranganathan S, Suthers PF, Maranas CD. OptForce: An optimization procedure for identifying all genetic manipulations leading to targeted overproductions. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6(4):e1000744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan S, Tee TW, Chowdhury A, Zomorrodi AR, Yoon JM, Fu Y, Shanks JV, Maranas CD. An integrated computational and experimental study for overproducing fatty acids in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2012;14(6):687–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San KY, Li M. Genetically engineered bacteria and method for synthesizing fatty acids. 2013. Patent WO 2013059218.

- San K-Y. Li M, Zhang X. Fatty acid production by recombinant microorganisms expressing plant hybrid thioesterase genes. 2011. Patent WO 2011116279.

- Steen EJ, Kang Y, Bokinsky G, Hu Z, Schirmer A, McClure A, Del Cardayre SB, Keasling JD. Microbial production of fatty-acid-derived fuels and chemicals from plant biomass. Nature. 2010;463(7280):559–562. doi: 10.1038/nature08721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torella JP, Ford TJ, Kim SN, Chen AM, Way JC, Silver PA. Tailored fatty acid synthesis via dynamic control of fatty acid elongation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(28):11290–11295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307129110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Gu Q, Wang W, Wong L, Bower AG, Collins CH, Koffas MA. Modular optimization of multi-gene pathways for fatty acids production in E. coli. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1409. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Ranganathan S, Fowler ZL, Maranas CD, Koffas MA. Genome-scale metabolic network modeling results in minimal interventions that cooperatively force carbon flux towards malonyl-CoA. Metab Eng. 2011;13(5):578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Cluett WR, Mahadevan R. EMILiO: A fast algorithm for genome-scale strain design. Metab Eng. 2011;13(3):272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngquist JT, Rose JP, Pfleger BF. Free fatty acid production in Escherichia coli under phosphate-limited conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(11):5149–5159. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4911-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Liu T, Zhu F, Khosla C. In vitro reconstitution and steady-state analysis of the fatty acid synthase from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(46):18643–18648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110852108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Carothers JM, Keasling JD. Design of a dynamic sensor-regulator system for production of chemicals and fuels derived from fatty acids. Nat Biotechnol. 2012a;30(4):354–359. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Ouellet M, Batth TS, Adams PD, Petzold CJ, Mukhopadhyay A, Keasling JD. Enhancing fatty acid production by the expression of the regulatory transcription factor FadR. Metab Eng. 2012b;14(6):653–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Rodriguez S, Keasling JD. Metabolic engineering of microbial pathways for advanced biofuels production. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011a;22(6):775–783. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Agrawal A, San KY. Improving fatty acid production in Escherichia coli through the overexpression of malonyl coA-acyl carrier protein transacylase. Biotechnol Prog. 2012c;28(1):60–65. doi: 10.1002/btpr.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li M, Agrawal A, San KY. Efficient free fatty acid production in Escherichia coli using plant acyl-ACP thioesterases. Metab Eng. 2011b;13(6):713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Li L, Liu Q, Qin W, Yang J, Cao Y, Jiang X, Zhao G, Xian M. Boosting the free fatty acid synthesis of Escherichia coli by expression of a cytosolic Acinetobacter baylyi thioesterase. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5(1):76–88. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]