Abstract

In many varieties of rice, the length of basal pores on the thecae just after anthesis is strongly correlated both with the percentage of florets receiving adequate pollen and with the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata and its variation (coefficient of variation). Therefore, the size of the basal pores is considered to be an important factor for the reliable self‐pollination of rice. We discuss how long basal pores may facilitate self‐ pollination.

Key words: Basal pore, theca, pollen dispersal, stigma, Oryza sativa L., rice, self‐pollination

INTRODUCTION

Rice anthers dehisce at the time of floret opening (Adair, 1934). Since the florets of rice are adichogamous, most of the florets are self‐pollinated at the time of floret opening (Jagoe, 1931). Synchrony between floret opening and anther dehiscence may contribute to the high rate of self‐pollination (Matsui et al., 2000a). However, the synchronization is not always perfect and some rice florets hybridize naturally (Akemine and Nakamura, 1924). The rate of natural hybridization varies among varieties of rice, suggesting that there is a difference in the reliability of self‐pollination among varieties (Akemine and Nakamura, 1924).

Rice pollination is susceptible to meteorological factors, such as temperature. High temperatures at the time of flowering inhibit the swelling of pollen grains (Matsui et al., 2000b), whereas low temperatures at the booting stage impede pollen growth (Shimazaki et al., 1964). Since the driving force for anther dehiscence is the swelling of pollen grains at the time of floret opening (Matsui et al., 1999a, b), temperature stress is considered to reduce the percentage of anthers dehiscing at the time of flowering (Shimazaki et al., 1964; Matsui et al., 2000b). Thus, high (>35 °C) and low (<20 °C) temperatures result in poor pollination and loss of yield (Horie et al., 1992, 1996). Insight into the characteristics of florets that control the reliability of self‐pollination may help breeders to improve the tolerance of florets to such temperature stresses.

This paper reports a correlation between morphological characteristics of floral organs and the reliability of self‐pollination in rice. The way in which these characteristics determine the reliability of self‐pollination in rice is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials

Eight Japanese indigenous varieties of rice (japonica) and four cultivars (japonica) produced at breeding stations in Japan were used in this study (Table 1). All seeds except those of ‘Kinmaze’ were obtained from Gene Bank of the National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences (Japan). Seeds of late varieties were sown on 3 May, whereas those of early varieties were sown on 14 June. Seedlings at the 5·4 leaf stage were transplanted in a circular pattern into 4 l pots, 20 seedlings per pot and grown in water‐logged soil. To avoid wind damage, plants were grown in a semi‐cylindrical house covered with cheesecloth (30 % shading) throughout the experimental period. Plants in each pot were supplied with 0·6g P2O5 as basal dressing, and 0·1 g N and K2O as top dressing on 27 June and 17 July for the first crop, and on 17 July for the second crop, to maintain a healthy leaf colour. During the vegetative stage, tillers were removed as they appeared. Ears emerged from mid‐August to early September.

Table 1.

Percentage of florets with more than 80 and 40 pollen grains deposited on the stigmata, and the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata

| Florets with | Florets with | Number of pollen grains | |||

| more than 80 | more than 40 | deposited on the stigmata | |||

| pollen grains | pollen grains | ||||

| on the | on the | Coefficient | |||

| Cultivar | stigmata (%) | stigmata (%) | Mean | of variation | |

| Mubouaikoku | Indigenous | 26·4 ± 21·0 | 53·3 ± 21·7 | 59·3 ± 27·7 | 84·1 ± 15·4 |

| Somewake | Indigenous | 77·3 ± 15·3 | 97·3 ± 6·0 | 137·0 ± 23·5 | 53·9 ± 15·9 |

| Ginbouzu | Indigenous | 60·8 ± 16·2 | 79·6 ± 10·6 | 130·3 ± 31·1 | 77·6 ± 18·3 |

| Kokuryomiyako | Indigenous | 67·3 ± 26·0 | 88·2 ± 17·4 | 168·5 ± 85·4 | 73·0 ± 26·4 |

| Komehikari | Indigenous | 95·0 ± 6·4 | 100·0 ± 0·0 | 207·8 ± 40·3 | 40·4 ± 9·6 |

| Husakushirazu | Indigenous | 51·9 ± 11·4 | 88·9 ± 8·2 | 109·7 ± 23·2 | 74·8 ± 19·7 |

| Tairaippon | Indigenous | 51·4 ± 13·2 | 83·8 ± 6·5 | 92·0 ± 13·4 | 58·1 ± 10·7 |

| Asahi | Indigenous | 75·6 ± 16·1 | 94·4 ± 5·0 | 144·1 ± 33·0 | 56·1 ± 5·2 |

| Homura3 | Breeding station* | 97·4 ± 3·5 | 100·0 ± 0·0 | 204·1 ± 60·2 | 44·4 ± 7·3 |

| Magatama | Breeding station | 87·8 ± 9·8 | 100·0 ± 0·0 | 194·6 ± 91·9 | 48·6 ± 3·5 |

| Kameji2 | Breeding station | 84·9 ± 9·9 | 97·4 ± 3·5 | 176·5 ± 89·0 | 52·6 ± 16·5 |

| Kinmaze | Breeding station | 95·0 ± 6·4 | 98·3 ± 3·3 | 187·2 ± 35·5 | 36·7 ± 7·3 |

Values are means ± s.d. of the data obtained on different days (n ≥ 3).

* Cultivars developed at a breeding station.

Experimental procedure

In each variety, 15 florets on primary branches were sampled about 3 h after the start of floret opening on one day during the flowering period. Florets closed about 1 h after they began to open. The number of thecae on which the stomium dehisced completely from apex to base (hereafter termed ‘longitudinally dehisced thecae’) was counted. For thecae on which the stomium dehisced on the apical and basal parts separately (‘cylindrically dehisced thecae’), the length of pores formed on the apical and basal parts was measured. Anthers from five florets selected at random from the 15 florets were used for this measurement. Stigmata from all 15 florets were then stained with cotton blue, and numbers of pollen grains on the stigmata were counted. Stigma length was also measured on the five florets used for measurements of pore length. Measurements were repeated more than three times for each rice variety during the flowering period. The percentage of florets with more than 40 and 80 pollen grains deposited on the stigmata, the distribution parameters of the number of pollen grains on the stigmata, and mean values of the morphological characteristics of the anther and stigma were calculated each day for each variety.

It is essential that more than ten pollen grains have germinated on the stigmata to ensure successful fertilization of a rice floret (Satake and Yoshida, 1978). Since approx. 50 % of the pollen grains on a stigma germinate, there must be over 20 pollen grains on a stigma to ensure fertilization. Thus, in this study, 40 pollen grains per floret was considered to be sufficient for fertilization, and 80 pollen grains to be ample. Means for each rice variety on the measurement days were calculated as the scores of that variety and were used for regression analysis.

For measurement of anther size, the third floret from the top of the first branch on the panicle was sampled on the day prior to floret opening (the day of floret opening was estimated from the position of the floret on the panicle). Length and width were measured after fixation in FAA (Matsui and Omasa, 2002). Eighteen anthers from three florets in each variety were measured. Means of the three florets per variety were used for regression analysis. Predictor variables in the multiple regression analysis were determined by stepwise regression.

RESULTS

The percentage of florets with more than 80 pollen grains on the stigmata after anthesis varied from 26 to 95 % in the indigenous varieties of rice, but was over 84 % in all the cultivars bred at the breeding stations (Table 1). The percentage of florets with more than 40 pollen grains on the stigmata varied from 53 to 100 % in the indigenous varieties, but it was over 97 % in all cultivars developed at the breeding stations. Percentages of florets with more than 80 pollen grains and with more than 40 pollen grains were both strongly correlated with the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata and the coefficient of variation of the number (Table 2). The number of pollen grains on stigmata was negatively correlated with the coefficient of variation of the number (r = –0·770, P < 0·01). The skewness and kurtosis of the distribution curve of pollen grain numbers did not correlate with the percentage of florets with more than 80 or 40 pollen grains on the stigmata (data not shown). Among the morphological characteristics of the anther and stigma, only the length of basal pores on thecae was correlated with the percentages of florets with more than 80 or 40 pollen grains on the stigmata (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation of the percentages of florets with more than 80 and 40 pollen grains on the stigmata with the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigma, its coefficient of variation and basal pore length

| Percentage of florets with >80 pollen grains on the stigmata | Percentage of florets with >40 pollen grains on the stigmata | |

| Number of pollen grains deposited on stigmata | 0·955*** | 0·837*** |

| Coefficient of variation of pollen grains deposited on stigmata | –0·889*** | –0·812** |

| Length of basal pore | 0·853*** | 0·803** |

*** P < 0·001; ** P < 0·01.

Among the coefficients of variation in the morphological characteristics of the floral organs, the coefficient of variation in the percentage of anthers with longitudinal dehiscence was largest, followed by that in the length of basal pores (Table 3). The coefficients of variation in length of the anthers and stigma were relatively small. The length of basal pores varied from 0·26 to 0·58 mm in the indigenous rice varieties, whereas it was over 0·45 mm in all cultivars bred at the breeding stations (Table 3). The length of the basal pore was highly correlated with the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata and its coefficient of variation (Table 4). The length of anthers varied from 1·46 to 2·52 mm (Table 3), but was not correlated with the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata or its coefficient of variation (Table 4). Anther width and the length of apical pores did not correlate with the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata or its coefficient of variation (data not shown). The percentage of thecae that dehisced longitudinally and the length of the stigma also did not correlate with pollen grain number or its coefficient of variation (Table 4). However, the length of the stigma correlated with the residual of the observed number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata from the number of pollen grains estimated by the length of basal pores (r = 0·628, P < 0·05). The number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata (Y) was given by the following regression:

Table 3.

Characteristics of floral organs and dehiscence of anther

| Cultivar | Length of anther (mm)* | Length of stigma (mm)† | Length of basal pore (mm)† | Percentage of thecae with longitudinal dehiscence† |

| Mubouaikoku | 1·46 ± 0·10 | 1·24 ± 0·04 | 0·257 ± 0·048 | 30·2 ± 10·3 |

| Somewake | 2·20 ± 0·04 | 1·16 ± 0·06 | 0·410 ± 0·025 | 1·7 ± 2·0 |

| Ginbouzu | 2·34 ± 0·08 | 1·15 ± 0·06 | 0·402 ± 0·038 | 1·1 ± 1·8 |

| Kokuryomiyak | 2·27 ± 0·05 | 1·15 ± 0·06 | 0·407 ± 0·043 | 2·6 ± 4·0 |

| Komehikari | 1·86 ± 0·07 | 1·17 ± 0·07 | 0·581 ± 0·022 | 77·0 ± 22·0 |

| Husakushirazu | 2·50 ± 0·04 | 1·32 ± 0·04 | 0·374 ± 0·028 | 0·0 ± 0·0 |

| Tairaippon | 1·93 ± 0·01 | 0·94 ± 0·08 | 0·448 ± 0·027 | 13·2 ± 9·3 |

| Asahi | 2·23 ± 0·06 | 1·11 ± 0·08 | 0·424 ± 0·038 | 0·0 ± 0·0 |

| Homura3 | 2·08 ± 0·08 | 1·46 ± 0·04 | 0·449 ± 0·036 | 7·9 ± 5·4 |

| Magatama | 2·31 ± 0·16 | 1·10 ± 0·05 | 0·511 ± 0·046 | 0·7 ± 1·7 |

| Kameji2 | 2·52 ± 0·08 | 1·08 ± 0·06 | 0·516 ± 0·052 | 2·3 ± 3·4 |

| Kinmaze | 1·86 ± 0·15 | 1·18 ± 0·06 | 0·579 ± 0·021 | 49·7 ± 8·3 |

| Mean | 2·13 | 1·17 | 0·447 | 15·5 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 14·4 | 10·9 | 20·4 | 158·3 |

* Values are means ± s.d. of florets (n = 3).

† Values are means ± s.d. of the data obtained on different days (n ≥ 3).

Table 4.

Correlation of the characteristics of floral organs with the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata and its coefficient of variation

| Number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata | ||

| Coefficient of | ||

| Characteristics of floral organ | Mean | variation |

| Length of anther | 0·280 n.s. | 0·038 n.s. |

| Length of basal pore | 0·811** | –0·876*** |

| Percentage of thecae with longitudinal dehiscence | 0·246 n.s. | –0·420 n.s. |

| Length of stigma | 0·189 n.s. | 0·019 n.s. |

*** P < 0·001; ** P < 0·01; n.s., not significant at the 5 % level.

Y = 464·1X1*** + 143·1X2* – 224·1, R = 0·894***

where X1 and X2 are the lengths of basal pores and stigmata, respectively (***P < 0·001; *P < 0·05).

The percentage of thecae that dehisced longitudinally varied greatly among rice varieties (0–77·0 %; Table 5). This percentage was closely correlated with the ratio of total pore length (apical pore length + basal pore length) to length of the whole anther (r = 0·925, P < 0·001), but not with the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata or its coefficient of variation (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

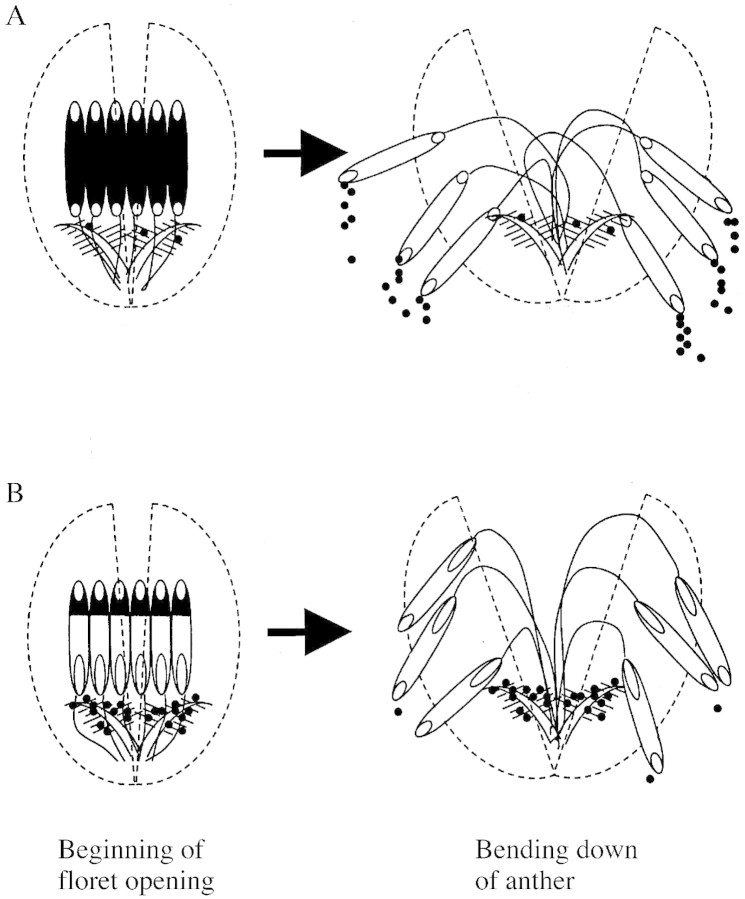

The percentage of florets with more than 40 or 80 pollen grains on the stigmata was closely correlated with the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata and its coefficient of variation. It was also closely correlated with length of the basal pore. Basal pores are located just above the stigmata and open at the time of floret opening (Morinaga and Kuriyama, 1944). Moreover, the basal pore is at the bottom of the theca when the anther stands erect at the time of floret opening. Therefore, pollen grains in anthers with large basal pores would readily drop out of the basal pores onto the stigmata (Fig. 1). In this way, many pollen grains may be released near the stigma in varieties of rice with large basal pores, thus increasing the chance of self‐pollination through the increased number of pollen grains on the stigmata, and decreasing the coefficient of variation of this value. In contrast, most of the pollen grains in anthers with small basal pores would remain in the anthers at the time of floret opening and would drop from the apical pores only after the anthers had bent over after full opening of the floret. Pollen shed in this way is usually scattered outside of the floret since the apical pores are usually outside the floret at this time.

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of the dispersal of pollen from anthers with small (A) and long (B) basal pores. In anthers with small basal pores, the majority of pollen grains remains in the thecae until the anther bends over, and is then dispersed widely by the wind. In contrast, in anthers with long basal pores, most of the pollen drops from the pores onto the stigmata at the beginning of the floret opening, i.e. at the beginning of anther dehiscence, and effects self‐pollination.

The present results also suggest that stigma length is related to the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata. Using F2 plants derived from crosses between low temperature‐tolerant and susceptible cultivars, Suzuki (1982) demonstrated that the length of the stigma is correlated with the degree of tolerance to low temperature at the booting stage. Stigma length may be correlated with the degree of tolerance to low temperature through the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata.

It has been suggested that cultivars with large anthers are tolerant to low temperature at the booting stage (Hashimoto, 1961; Suzuki, 1981; Tanno et al., 1999) and to high temperature at the flowering stage (Matsui and Omasa, 2002). Among rice varieties, the number of pollen grains per anther was positively correlated with the length of the anther (Suzuki, 1981). Since the direct cause of floret sterility under temperature stress is a decrease in the number of pollen grains that germinate on the stigma (Shimazaki et al., 1964; Satake and Yoshida, 1978), it was assumed that cultivars with large anthers are tolerant to temperature stress because they have a large number of pollen grains per anther, which compensates for the reduction in the number of pollen grains that germinate (Suzuki, 1981; Tanno et al., 1999; Matsui and Omasa, 2002). In the present experiment, however, the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata depended largely on the length of the basal pore. It may be that this compensation also holds for cultivars with similar basal pore lengths. However, the coefficient of variation in basal pore length was relatively large as compared with that for anther and stigma length. The large coefficient of variation in the length of the basal pore may have over‐emphasized the effect of basal pore size on the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata and its coefficient of variation.

Longitudinal dehiscence of thecae seems to aid pollination because the area of the opening is large. However, the percentage of thecae showing longitudinal dehiscence did not correlate with the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata and its coefficient of variation. It was correlated with the ratio of the total length of the pores to the length of the anther, indicating that longitudinal dehiscence was the result of the joining of the apical and basal pores. The shortness of the anther may be offset against the advantage of possessing a large opening in terms of the number of pollen grains deposited on the stigmata and its coefficient of variation.

The small basal pores on the thecae would make self‐pollination unreliable. Unreliable self‐pollination increases the possibility of cross‐pollination in rice (Akemine and Nakamura, 1924). Moreover, an anther with small basal pores may retain many pollen grains until the apical pores are outside of the floret before releasing them. Pollen grains released from the apical pores may scatter readily in the air and may effect cross‐pollination (see Fig. 2). Kato and Namai (1987) assumed that at flowering, residual pollen in the anthers would be scattered further in the air than pollen released in the floret. Among the 12 rice varieties used in the present experiment, cultivars developed at the breeding stations tended to have large basal pores. Plants with small basal pores may be more likely to be cross‐pollinated and would be weeded out by the breeders in the process of pure line selection and fixation.

Supplementary Material

Received: 30 September 2002; Returned for revision: 6 November 2002; Accepted: 2 December 2002

References

- AdairCR.1934. Studies on blooming in rice. Journal of the American Society of Agronomy 26: 965–973. [Google Scholar]

- AkemineM, Nakamura S.1924. Degree of natural cross pollination and its cause. Journal of the Society of Agriculture and Forestry, Sapporo, Japan 16: 109–144 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 3.HashimotoK.1961. On size of anther in rice plant varieties. Bulletin of Hokkaido Study Meeting of Breeding and Crop Science 2: 11 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- HorieT, Yajima M, Nakagawa H.1992. Yield forecasting. Agricultural Systems 40: 211–236. [Google Scholar]

- HorieT, Matsui T, Nakagawa H, Omasa K.1996. Effect of elevated CO2 and global climate change on rice yield in Japan. In: Omasa K, Kai K, Toda H, Uchijima Z, Yoshino M, eds. Climate change and plants in East Asia Tokyo: Springer‐Verlag, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- JagoeRB.1931. Hybridization of selected strain of padi. The Malayan Agricultural Journal 19: 530–534. [Google Scholar]

- KatoH, Namai H.1987. Floral characteristics and environmental factors for increasing natural out‐crossing rate for F1 hybrid seed production of rice Oryza sativa L. Japanese Journal of Breeding 37: 318–330 (in Japanese, with English summary). [Google Scholar]

- MatsuiT, Omasa K.2002. Rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars tolerant to a high temperature at flowering: Anther characteristics. Annals of Botany 89: 683–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MatsuiT, Omasa K, Horie T.1999a Rapid swelling of pollen grains in response to floret opening unfolds locule in rice. Plant Production Science 2: 196–199. [Google Scholar]

- MatsuiT, Omasa K, Horie T.1999b Mechanism of anther dehiscence in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Annals of Botany 84: 501–506. [Google Scholar]

- MatsuiT, Omasa K, Horie T.2000a Anther dehiscence in two‐rowed barley (Hordeumdisticum) triggered by mechanical stimulation. Journal of Experimental Botany 51: 1319–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MatsuiT, Omasa K, Horie T.2000b High temperatures at flowering inhibit swelling of pollen grains, a driving force for thecae dehiscence in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Production Science 3: 430–434. [Google Scholar]

- MorinagaT, Kuriyama H.1944. On the anthers of Oryza species. The Botanical Magazine 58: 90–92 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- SatakeT, Yoshida S.1978. High temperature‐induced sterility in indica rice at flowering. Japanese Journal ofCrop Science 47: 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- ShimazakiY, Satake T, Ito N, Doi Y, Watanabe K.1964. Sterile spikelets in rice plants induced by low temperature during the booting stage. Research Bulletin of the Hokkaido National Agricultural Experiment Station 83: 1–9 (in Japanese, with English summary). [Google Scholar]

- SuzukiS.1981. Cold tolerance in rice plants with special reference to the floral characters. I. Varietal differences in anther and stigma length and effects of planting densities on these characters. Japanese Journal of Breeding 31: 57–64 (in Japanese, with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- SuzukiS.1982. Cold tolerance in rice plants with special reference to the floral characters. II. Relations between floral characters and the degree of cold tolerance in segregating generations. Japanese Journal of Breeding 32: 9–16 (in Japanese, with English summary). [Google Scholar]

- TannoH, Xiong J, Dai L, Ye C.1999. Some characteristics of cool weather‐tolerant rice varieties in Yunnan province, China. Japanese Journal of Crop Science 68: 508–514 (in Japanese, with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.