Abstract

Background and Purpose

As a newer component of the renin–angiotensin system, angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7) ] has been shown to facilitate angiogenesis and protect against ischaemic damage in peripheral tissues. However, the role of Ang-(1–7) in brain angiogenesis remains unclear. The aim of this study was to investigate whether Ang-(1–7) could promote angiogenesis in brain, thus inducing tolerance against focal cerebral ischaemia.

Experimental Approach

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were i.c.v. infused with Ang-(1–7), A-779 (a Mas receptor antagonist), L-NIO, a specific endothelial NOS (eNOS) inhibitor, endostatin (an anti-angiogenic compound) or vehicle, alone or simultaneously, for 1–4 weeks. Capillary density, endothelial cell proliferation and key components of eNOS pathway in the brain were evaluated. Afterwards, rats were subjected to permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (pMCAO), and regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF), infarct volume and neurological deficits were measured 24 h later.

Key Results

Infusion of Ang-(1–7) for 4 weeks significantly increased brain capillary density via promoting endothelial cell proliferation, which was accompanied by eNOS activation and up-regulation of NO and VEGF in brain. These effects were abolished by A-779 or L-NIO. More importantly, Ang-(1–7) improved rCBF and decreased infarct volume and neurological deficits after pMCAO, which could be reversed by A-779, L-NIO or endostatin.

Conclusions and Implications

This is the first evidence that Ang-(1–7) promotes brain angiogenesis via a Mas/eNOS-dependent pathway, which enhances tolerance against subsequent cerebral ischaemia. These findings highlight brain Ang-(1–7)/Mas signalling as a potential target in stroke prevention.

Introduction

Ischaemic stroke is a major cause of human death and disability worldwide (Addo et al., 2012). To date, limited clinical intervention is available to reduce brain damage after stroke onset. In recent years, increasing attention has been focused on development of preventive strategies, which is targeted to ameliorate the impact of future stroke events by enhancement of ischaemic tolerance. Accumulating evidence suggests that patients with stroke with a greater cerebral capillary density have a better ischaemic tolerance than subjects with lower capillary density (Krupinski et al., 1994). Meanwhile, animal studies indicate that improvement of cerebral capillary density via therapeutic angiogenesis leads to a better outcome after ischaemic insults (Li et al., 2008). The underlying mechanisms are that the increased brain capillary density prevents reduction of regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) and maintains oxygen supply during cerebral ischaemia, thus ameliorating ischaemic brain damage (Wang et al., 2005; Zechariah et al., 2013).

As a more recently identified bioactive peptide of the renin–angiotensin system, angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7) ] is generated mainly from angiotensin II by ACE-2 and binds to the GPCR Mas to exert its physiological functions (Santos et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2011; Renno et al., 2012; receptor nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2013). Emerging evidence suggests a potential role of Ang-(1–7) in the process of angiogenesis. In vitro, Chen et al. found that overexpression of ACE2 led to an elevation of Ang-(1–7) levels, which subsequently improved the migration and tube formation of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) (Chen et al., 2013). In the heart, endogenous Ang-(1–7) participated in angiogenesis, facilitating cardiac repair and improving ventricular function (Zhao et al., 2013). In addition to the heart, Ang-(1–7) and Mas receptors are also present as endogenous constituents of brain. However, the role of Ang-(1–7) in brain angiogenesis remains elusive, thus far. Hence, the main purpose of the present study was to investigate the effects of chronic Ang-(1–7) infusion on angiogenesis in rat brain. For the first time, we report that Ang-(1–7) promotes endothelial cell proliferation and increases brain capillary density via a Mas/endothelial NOS (eNOS)-dependent pathway. More importantly, we found that Ang-(1–7)-induced brain angiogenesis attenuated the reduction of rCBF during subsequent ischaemia and resulted in improvement of stroke outcome.

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Management Committee of Qingdao Municipal Hospital (Permit No. QMHEC-130427). All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2014a; McGrath et al., 2010; Hooijmans et al., 2011). A total of 246 animals were used in the experiments described here. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–280 g, purchased from the Experimental Animals Center of Nanjing Medical University) were maintained in individually ventilated cages at 20–24°C and relative humidity (30–70%) with a 12 h light/dark cycle, and given free access to food and water.

Experimental groups

The rats were randomly allocated to eight experimental groups using a random number table generated by the SPSS software 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) as described (Jiang et al., 2014a,b2014a). For drug administration, rats were anaesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate (3.5 mL·kg−1, i.p.), and placed in a stereotactic frame (David Kopf Instrument Inc., Tujunga, CA, USA). Implantation of osmotic pumps was performed by surgeons who were unaware of the experimental groups, as previously described (Jiang et al., 2012). Ang-(1–7) (1.11 nmol·L−1; 0.25 μL·h−1), A-779 (1.14 nmol·L−1; 0.25 μL·h−1), L-NIO (10 μmol·L−1; 0.25 μL·h−1), endostatin (0.6 mg·L−1; 0.25 μL·h−1) or aCSF was continuously infused into the right lateral cerebral ventricle by osmotic pumps until the animals were killed or subjected to permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (pMCAO; for detailed administration protocol, see Supporting Information Fig. S1). During drug infusion, no signs of neurotoxicity or intracranial hypertension were observed in animals. The dose for Ang-(1–7) (1.11 nmol·L−1) was chosen based on our previous studies showing that Ang-(1–7) at this dose could effectively activate the Mas/eNOS signalling pathway in brain (Zhang et al., 2008). Meanwhile, the dose for A-779 (1.14 nmol·L−1) was selected according our previous findings that A-779 at this dose could effectively block most of the effects mediated by Ang-(1–7) (1.11 nM) (Jiang et al., 2012; 2013b,c). The dose for L-NIO and endostatin was determined according to studies by Siamwala et al. (2013) and O'Reilly et al. (1997) respectively.

BP measurement

BP of conscious rats was measured by a tail-cuff measurement system (BP-2000; Visitech Systems Inc. Apex, NC, USA) once a week by observers who were unaware of the experimental groups, as previously described (Jiang et al., 2013b,c). Briefly, unanaesthetized rats were placed in a holding device mounted on a thermostatically controlled warming plate to make the pulsations of the tail artery detectable. Tail cuffs were fixed on animals, and animals were allowed to acclimate to cuffs for 10 min prior to each pressure recording session. Systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) were measured, and mean BP (MAP) was automatically calculated using the following formula: MAP = (SBP + 2 × DBP) / 3.

Measurement of cerebral capillary density and endothelial cell proliferation

Cerebral capillary density was assessed by CD31 (an endothelial cell marker) immunofluorescence staining. Endothelial cell proliferation was evaluated by double immunofluorescence staining with CD31 and 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU), a marker for cell proliferation (Zeng et al., 2010). At 1, 2 or 4 weeks after infusion, some rats were received a single injection of EdU (100 mg·kg−1), then were anaesthetized and transcardially perfused with PBS (n = 6 per group). Afterwards, the brains were removed and were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution overnight. After dehydrated in alcohol, the brains were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5 μm sections. Sections were then incubated with a Cell-Light™ (Riobio Inc., Guangzhou, China) reaction cocktail for 30 min for EdU staining. For labelling of CD31, the sections were then incubated with mouse anti-CD31 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) at 1:400 dilution in the blocking serum overnight at 4°C. After washing, sections were incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h and sealed with a coverslip. The slides were analysed with a fluorescence microscopy. Quantification of cerebral capillary density and endothelial cell proliferation was performed by observers who were unaware of the experimental groups using a protocol described by Zechariah et al. (2013). Briefly, three regions of interest (ROI) at the size of 500 × 500 μm in the cerebral cortex were chosen from three separate brain coronal sections (−0.8, −1.8 and −2.8 mm from bregma). These areas were selected as ROIs because they are directly perfused by the MCA, and pMCAO will lead to the irreversible ischaemic damage in these areas (Longa et al., 1989). More importantly, these areas play an irreplaceable role in sensory and motor functions, and ischaemic damage within these areas is closely associated with sensory and motor deficiency, the most apparent symptom of ischaemic stroke (Harrison et al., 2013). The numbers of CD31 + capillary as well as Edu + CD31 + capillary were manually counted, and cerebral capillary density for each rat was calculated as the mean of the capillary counts obtained from the nine ROIs mentioned earlier. Meanwhile, endothelial cell proliferation was expressed as the percentage of Edu + CD31 + capillary numbers in the nine ROIs mentioned earlier. It should be noted that the data of vehicle group in Supporting Information Fig. S3 were produced in response to a reviewer's comment, and were therefore not contemporaneous with the data of the other two groups.

Assessment of Ang-(1–7), NO and VEGF levels

For measurement of Ang-(1–7) levels, the rat brain was cut into halves, and the cortex and hippocampus were homogenized separately. The concentration of Ang-(1–7) was detected by a specific elisa kits (S-1330; Bachem Inc., Torrance, CA, USA).

For assessment of NO and VEGF levels, the brain of each rat was cut into halves and was homogenized. The NO level was assessed by a colorimetric detection kit (Jiancheng Inc., Nanjing City, China) as described (Zhang et al., 2008). The concentration of VEGF was measured by specific elisa kits (ab100786, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, UK) according to the technical manuals provided by the manufacturers.

Western blot analysis

The brain of each rat was cut into halves and was homogenized. The total proteins were extracted by RIPA lysis buffer. Samples were separated on SDS polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and blocked in 5% BSA solution. Membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies (Supporting Information Table S1). After washing, membranes were then incubated with HRP-coupled secondary antibody for another 2 h. Protein bands were detected with chemiluminescent HRP substrate for 5 min. The band intensity was analysed using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and normalized to β-actin.

pMCAO and rCBF measurement

At 4 weeks after infusion, some rats were anaesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate (3.5 mL·kg−1, i.p.) again. The depth of anaesthesia was monitored by assessing the withdrawal reflex to footpad pinching. pMCAO was performed by surgeons who were unaware of the experimental groups, as previously described (Jiang et al., 2012). Rats in the sham-operated group were subjected to the filament insertion into the internal carotid artery but with no reduction in rCBF. rCBF was determined in the core region (2 mm caudal to bregma and 6 mm lateral to midline) and peripheral region (2 mm caudal to bregma and 3 mm lateral to midline) of the MCA territory before and after pMCAO by a laser-Doppler probe attached to the thinned skull (Jiang et al., 2012). pMCAO induction was considered successful if an >80% reduction in rCBF was observed in the core region of MCA territory after occlusion. During the pMCAO procedure, body temperature was maintained in the range of 37.0 ± 0.5°C with a heating pad until rats were killed.

Infarct volume assessment and neurobehavioural testing

At 24 h after pMCAO, 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining was performed to assess the infarct volume by investigators who were unaware of the experimental groups, as previously described (Gao et al., 2012). The infarct volume was evaluated by Image Pro-Plus 5.1 analysis system (Media Cybernetics Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) using Swanson's method which corrects for oedema (Swanson et al., 1990).

Neurobehavioural tests were performed at 24 h after pMCAO using a 5-point scale by an investigator who was unaware of experimental groups, as previously described (Jiang et al., 2012).

Data analysis

With the exception of neurological deficit, all data are expressed as mean ± SD. Data were analysed with the SPSS software 16.0 (SPSS Inc.). Statistically significant differences were evaluated by an independent sample t-test or one-way anova followed by least significant difference post hoc test. For neurological deficits, Mann–Whitney U-test was used for comparisons between two groups. Power calculation was performed by STPLAN version 4.3 software (The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Materials

Ang-(1–7), A-779 (an antagonist of Mas receptors), N5-(1-iminoethyl)-L-ornithine (L-NIO, a specific eNOS inhibitor) and endostatin (an anti-angiogenic compound) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and were dissolved in an artificial CSF (aCSF).

Results

Effects of Ang-(1–7) infusion on mean arterial BP and brain Ang-(1–7) concentration

As indicated by Supporting Information Fig. S2A, infusion of Ang-(1–7) did not significantly alter the MAP of rats during the whole study. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S2B, 4 weeks infusion significantly elevated Ang-(1–7) concentration in hippocampus and cerebral cortex of the ipsilateral hemisphere by 4.8- and 3.6-fold, respectively, whereas Ang-(1–7) levels in the contralateral hemisphere stayed unchanged (Supporting Information Fig. S2B).

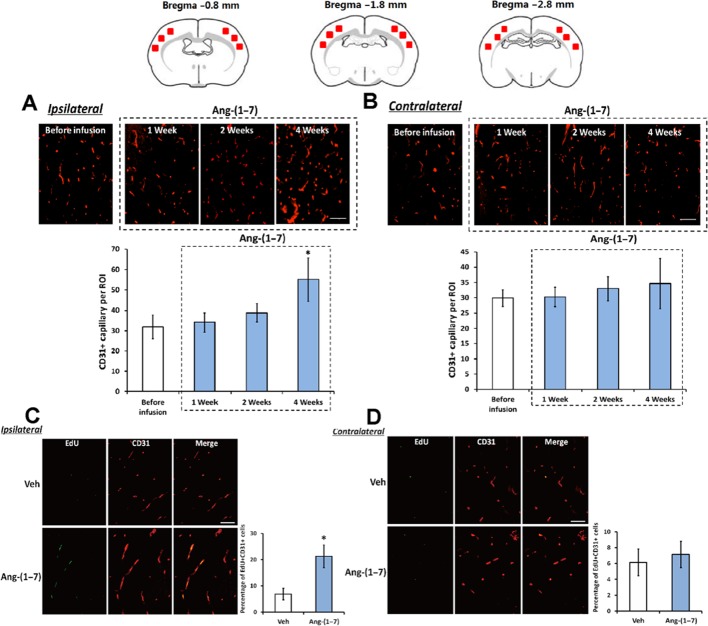

Infusion of Ang-(1–7) increased brain angiogenesis

Brain angiogenesis was assessed by brain capillary density and endothelial cell proliferation. As indicated by Figure 1A, a significant increase in capillary density in the ipsilateral hemisphere was observed after 4 weeks infusion of Ang-(1–7) (55 ± 10.7 vs. 31.9 ± 5.9 in ROI). Meanwhile, the percentage of EdU +/CD31 + cells in the ipsilateral hemisphere was also markedly increased after 4 weeks infusion of Ang-(1–7) (21.3 ± 4.3% vs. 6.9 ± 2.2%, Figure 1C). However, the capillary density and percentage of EdU +/CD31 + cells in the contralateral hemisphere were not influenced by 4 weeks Ang-(1–7) infusion (Figure 1B and D).

Figure 1.

Ang-(1–7) increased cerebral capillary density and promoted endothelial cell proliferation in the ipsilateral hemisphere. Rats were infused with Ang-(1–7) for 1, 2 or 4 weeks, and the brain was removed and fixed. As indicated by the atlas on the top of this figure, three regions of interest (ROIs; size 500 × 500 μm) in the cerebral cortex (indicated by red box) were chosen from three separate brain coronal sections (−0.8, −1.8 and −2.8 mm from bregma). Capillary density in these ROIs of the ipsilateral hemisphere (A) and the contralateral hemisphere (B) was assessed by CD31 immunofluorescence staining. Bars: 100 μm. In addition, rats were infused with vehicle or Ang-(1–7) 4 weeks, and endothelial cell proliferation in these ROIs of the ipsilateral hemisphere (C) and the contralateral hemisphere (D) was evaluated by double immunofluorescence staining with CD31 and EdU. Bars: 50 μm. Data shown are means ± SD; n = 6 per group; *P < 0.05 significantly different from vehicle-treated rats.

Ang-(1–7)-induced angiogenesis was mediated by a Mas/eNOS-dependent pathway

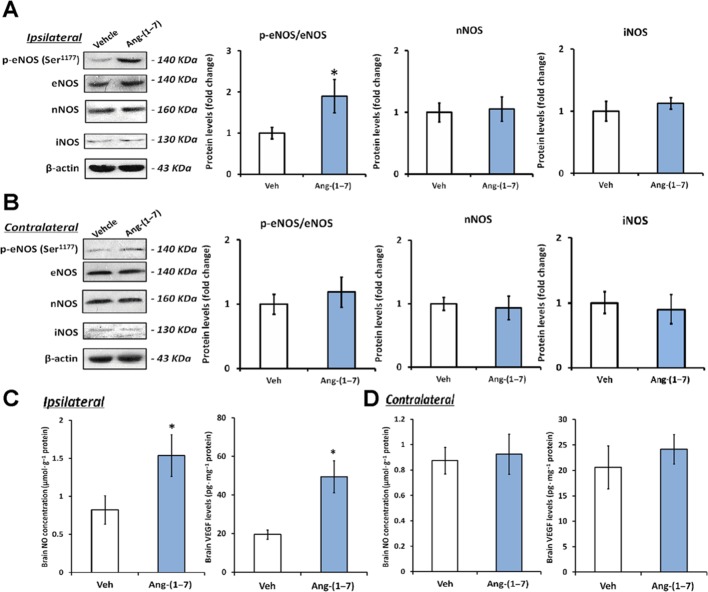

As revealed by Figure 2A, the ratio of p-eNOS (Ser1177)/eNOS in the ipsilateral hemisphere was increased by 1.9-fold after 4 weeks Ang-(1–7) infusion. Meanwhile, Ang-(1–7) also induced an obvious increase in NO (1.5 ± 0.3 vs. 0.8 ± 0.2 μmol·g−1 protein) and VEGF (49.4 ± 8.3 vs. 19.5 ± 2.4 pg·mg−1 protein) levels in the ipsilateral hemisphere (Figure 2C). However, the expression of nNOS and iNOS in the ipsilateral hemisphere stayed unchanged after 4 weeks infusion of Ang-(1–7) (Figure 2A). It should be noted that Ang-(1–7) did not cause significant influence on aforementioned parameters in the contralateral hemisphere (Figure 2B and D).

Figure 2.

Ang-(1–7) infusion activated eNOS and increased levels of NO and VEGF in the ipsilateral hemisphere. Rats were infused with Ang-(1–7) or vehicle for 4 weeks. The ratios of p-eNOS (Ser1177)/eNOS as well as the protein levels of nNOS and iNOS in the ipsilateral hemisphere (A) and the contralateral hemisphere (B) were evaluated by Western blot. (C, D) The levels of NO and VEGF in the ipsilateral hemisphere and the contralateral hemisphere. Data shown are means ± SD; n = 6 per group; *P < 0.05 significantly different from vehicle-treated rats.

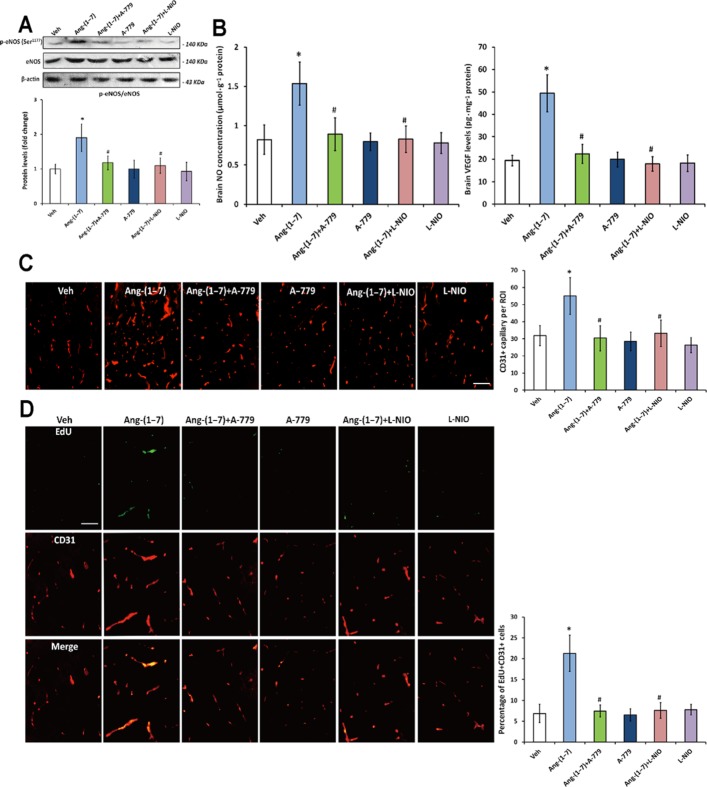

To determine whether Mas receptor was involved in Ang-(1–7)-induced angiogenesis, rats were co-treated with Ang-(1–7) and Mas antagonist A-779 for 4 weeks. A-779 co-treatment significantly reduced the Ang-(1–7)-induced increase in ratio of p-eNOS (Ser1177)/eNOS as well as NO and VEGF levels (Figure 3A and B). Besides, the Ang-(1–7)-induced elevation in capillary density and EdU +/CD31 + cell percentage in brain was also abolished by A-779 (Figure 3C and D). It should be noted that A-779 itself or in combination with Ang-(1–7) did not significantly affect the parameters in both hemispheres (Figure 3) mentioned earlier.

Figure 3.

Effects of A-779 and L-NIO on Ang-(1–7)-induced angiogenesis. Rats were co-treated with Ang-(1–7) and Mas antagonist A-779 or eNOS inhibitor L-NIO for 4 weeks. (A) The p-eNOS (Ser1177)/eNOS ratio in the ipsilateral hemisphere after co-treatment with A-779 or L-NIO. (B) The levels of NO and VEGF in the ipsilateral hemisphere after co-treatment with A-779 or L-NIO. (C) Capillary density in cerebral cortex of the ipsilateral hemisphere after co-treatment with A-779 or L-NIO was assessed by CD31 immunofluorescence staining. (D) Endothelial cell proliferation in cerebral cortex of the ipsilateral hemisphere after co-treatment with A-779 or L-NIO was evaluated by double immunofluorescence staining with CD31 and EdU. Data shown are means ± SD; n = 6 per group; *P < 0.05 significantly different from Ang-(1–7)-treated rats.

To further demonstrate the association of eNOS-mediated signalling with Ang-(1–7)-induced angiogenesis, rats were co-treated with Ang-(1–7) and L-NIO for 4 weeks. Co-treatment with L-NIO markedly inhibited the increase in p-eNOS (Ser1177)/eNOS ratio (Figure 3A). Meanwhile, the Ang-(1–7)-induced changes in NO and VEGF levels were also abolished by L-NIO (Figure 3B). More importantly, the Ang-(1–7)-induced angiogenesis was attenuated by L-NIO, as the capillary density and the percentage of EdU +/CD31 + cells in the brain were blunted by L-NIO co-treatment (Figure 3C and D). It is worthy to note that L-NIO alone or in combination with Ang-(1–7) did not influence the parameters in both hemispheres (Figure 3) mentioned earlier.

Ang-(1–7)-induced angiogenesis attenuated the reduction of rCBF and improved stroke outcome after pMCAO

After 4 weeks infusion of Ang-(1–7), rats were subjected to pMCAO. This time-point was selected based on the observation mentioned earlier that 4 weeks infusion of Ang-(1–7) significant promoted brain angiogenesis (Figure 1A).

A total of 10 rats died before completion of the experiment and were excluded from the study: one rat (8.3%) in group 1, one rat (8.3%) in group 2, two rats in group 3 (16.7%), one rat in group 4 (8.3%), one rat in group 5 (8.3%), two rats in group 6 (16.7%), one rat in group 7 (8.3%) and one rat in group 8 (8.3%). Post-mortem examinations did not reveal the occurrence of intracerebral or subarachnoid haemorrhage in any of these animals, and no significant differences were found among mortality of each group.

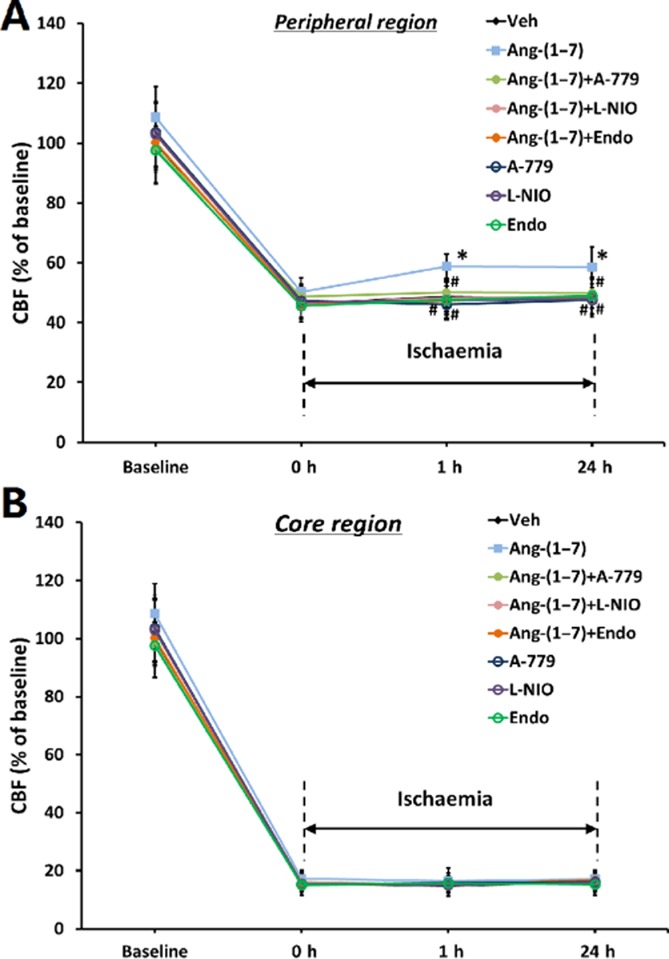

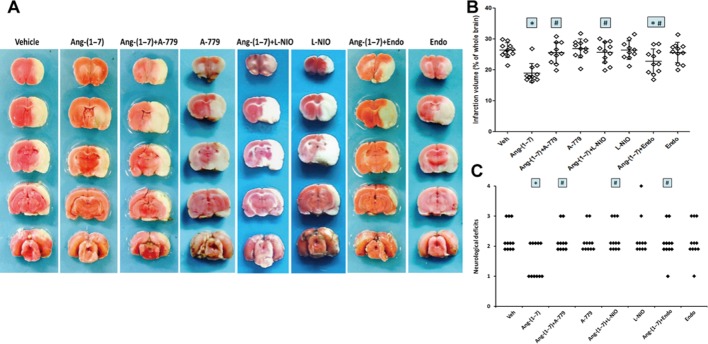

During pMCAO, rCBF was measured in the core region and peripheral region of the MCA territory. As demonstrated by Figure 4A, rCBF immediately decreased to approximately 15% of the baseline in the core region and to approximately 47% in the peripheral region in vehicle-treated rats at the onset of pMCAO, and continued for at least 24 h after pMCAO. Ang-(1–7) infusion attenuated the reduction in rCBF in the peripheral region after pMCAO (at 1 h after pMCAO: 58.8 ± 4% vs. 48.8 ± 5.2% of baseline, P < 0.05; at 24 h after pMCAO: 58.5 ± 6.8% vs. 48.1 ± 6.3% of baseline, P < 0.05). However, the reduction of rCBF in the core region of the MCA territory after pMCAO was not significantly attenuated by Ang-(1–7) (Figure 4B). At 24 h after pMCAO, TTC staining and neurobehavioural testing were used to assess stroke outcome. As shown in Figure 5A and B, chronic infusion of Ang-(1–7) led to a significant reduction in infarct volume (18.8 ± 2.9% vs. 26.4 ± 2.4% of the whole brain). Meanwhile, an obvious amelioration in neurological deficits was observed in Ang-(1–7)-infused rats (Figure 5C).

Figure 4.

Ang-(1–7) infusion attenuated the reduction of rCBF after pMCAO. Rats were co-treated with Ang-(1–7) and Mas receptor antagonist A-779, eNOS inhibitor L-NIO or an anti-angiogenic compound endostatin (Endo) for 4 weeks, and were subjected to pMCAO. CBF was measured in the peripheral region (A) and core region (B) of the MCA territory before and after pMCAO. Data are expressed as a percentage of basal CBF in vehicle-treated rats. Data shown are means ± SD; n = 10-11 per group; *P < 0.05 significantly different from vehicle-treated rats. #P < 0.05 significantly different from Ang-(1–7)-treated rats.

Figure 5.

Ang-(1–7) infusion reduced infarct volume and neurological deficits after pMCAO. Rats were co-treated with Ang-(1–7) and Mas antagonist A-779, eNOS inhibitor L-NIO or an anti-angiogenic compound endostatin (Endo) for 4 weeks, and were subjected to pMCAO. (A) Representative TTC images showing the mean infarct volume in each group at 24 h after pMCAO. (B) Infarct volume in each group at 24 h after pMCAO. (C) The distribution of neurological deficit score in each group at 24 h after pMCAO. With the exception of neurological deficit, Data shown are means ± SD; n = 10-11 per group; *P < 0.05 significantly different from vehicle-treated rats. #P < 0.05 significantly different from Ang-(1–7)-treated rats.

To examine the possibility that the improvement of rCBF and stroke outcome were associated with Ang-(1–7)-induced angiogenesis, rats were co-treated with an anti-angiogenic compound endostatin, L-NIO or A-779 for 4 weeks before pMCAO. The inhibition of endostatin on Ang-(1–7)-induced increase in capillary density had been confirmed (Supporting Information Fig. S3). As indicated by Figure 4, the Ang-(1–7)-induced improvement in rCBF was fully reversed by endostatin, L-NIO or A-779. Meanwhile, the Ang-(1–7)-induced reduction of infarct volume and neurologic deficits was partly abolished by endostatin while L-NIO and A-779 completed reversed the alterations in infarct volume and neurologic deficits caused by Ang-(1–7) (Figure 5). It is worthy to note that endostatin, L-NIO and A-779 alone did not alter infarct volume or neurologic deficits (Figure 5).

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that infusion of Ang-(1–7) for 4 weeks promoted brain angiogenesis via a Mas/eNOS-dependent pathway, which attenuated the reduction of rCBF and improved stroke outcome after pMCAO.

For the first time, we demonstrated that Ang-(1–7) promoted angiogenesis in brain, as an enhancement of endothelial cell proliferation and increased brain capillary density were observed after 4 weeks infusion of Ang-(1–7). These results were supported by earlier results from an in vitro study in which overexpression of ACE2 improved EPC migration and tube formation through elevating Ang-(1–7) levels (Chen et al., 2013). Besides, more direct evidence has come from a recent study by Zhao et al. that demonstrated that endogenous Ang-(1–7) facilitated angiogenesis via increased endothelial cell proliferation in heart (Zhao et al., 2013). However, in contrast to our findings, several lines of evidence have suggested an anti-proliferative property of Ang-(1–7), as it directly inhibited the growth of cancer cells such as SK-LU-1, A549 and SKMES-1 cells in vitro (Passos-Silva et al., 2013). This discrepancy might be ascribed to the differences between cancer cells and endothelial cells in response to Ang-(1–7).

We then investigated the underlying mechanisms by which Ang-(1–7) promoted angiogenesis and found that Ang-(1–7) infusion significantly enhanced eNOS activity and NO generation in brain. Meanwhile, the level of VEGF, a main downstream effector of eNOS, was also increased in brain after Ang-(1–7) infusion. All these effects were abolished by A-779, implying that eNOS was a downstream effector of Ang-(1–7)/Mas signalling. These observations were compatible with a previous study in which Ang-(1–7) activated eNOS by binding with Mas receptors in human aortic endothelial cells (Sampaio et al., 2007). More recent studies have demonstrated that brain eNOS activity was enhanced by overexpression of ACE2 or infusion of Ang-(1–7), which can be suppressed by A-779, further indicating that Ang-(1–7) could directly activate eNOS through Mas receptors in brain (Zhang et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2010). To further elucidate the association between eNOS activation and Ang-(1–7)-induced brain angiogenesis, a potent eNOS inhibitor L-NIO was used in our experiments. As expected, the effects of Ang-(1–7) on NO and VEGF were abolished by L-NIO. More importantly, co-treatment with L-NIO completely reversed the pro-angiogenic effects of Ang-(1–7). These findings indicated that Ang-(1–7) promoted angiogenesis in an eNOS-dependent manner. As an important effector downstream of Ang-(1–7)/Mas signalling, eNOS plays an irreplaceable role in angiogenesis. Pharmacological inhibition of eNOS was able to block the formation of new vessels while eNOS-deficient mice exhibited significant impairment in their angiogenic response under pathological conditions (Zhang et al., 2003; Gertz et al., 2006). In contrast, activation of eNOS could enhance NO generation, which subsequently promoted VEGF synthesis and facilitated the process of angiogenesis (Namba et al., 2003; Thibeault et al., 2010).

Ang-(1–7) attenuated the reduction of rCBF in the peripheral region of MCA territory after pMCAO, an effect which was abolished by A-779 or L-NIO. Meanwhile, we also found that endostatin, an anti-angiogenic compound, could fully reverse the Ang-(1–7)-induced improvement in rCBF, establishing a causal relation between Ang-(1–7)-induced angiogenesis and rCBF improvement. As a vasoactive peptide, it is possible that Ang-(1–7) improved rCBF via other mechanisms, such as vasodilation of cerebral blood vessels. However, in previous studies, we and others found that Ang-(1–7) at the current dose (1.11 nM) did not induce vasodilatation in brain (Mecca et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2012). Hence, it is unlikely that Ang-(1–7) improved rCBF through its vasodilatory effects in this model.

Accumulating evidence suggested that maintaining rCBF after pMCAO is associated with a better stroke outcome, as enhanced rCBF led to the improvement in blood and oxygen supply, which stabilized cerebral energy state and reduced neuronal damage in the peri-infarct regions (Li et al., 2008; Zechariah et al., 2013). In this study, reduced infarct volume and neurological deficits were observed in rats after Ang-(1–7) infusion. Interestingly, the improved stroke outcome was partly attenuated by endostatin and completely reversed by A-779 and L-NIO. These findings indicated that promotion of angiogenesis only represented part of the neuroprotective mechanisms of Ang-(1–7). In other words, apart from its pro-angiogenic actions, Ang-(1–7) may exert its neuroprotection through other Mas/eNOS-dependent mechanisms, such as modulation of inflammatory response and oxidative stress in brain (El-Hashim et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2012; 2013a; Regenhardt et al., 2013a,b; Simoes e Silva et al., 2013; Sumners et al., 2013).

Lastly, an interesting observation should be noted. In this study, infusion of Ang-(1–7) into the right lateral cerebral ventricle significantly increased the levels of this peptide in the ipsilateral hemisphere, whereas the Ang-(1–7) levels in the contralateral hemisphere were unchanged. Correspondingly, the Ang-(1–7)-induced angiogenesis was also limited to the ipsilateral hemisphere. This phenomenon can be explained as follows: first, as the right and left lateral cerebral ventricles of Sprague-Dawley rats are not directly connected, the solution infused into one lateral cerebral ventricle cannot directly circulate into the other one. Second, although a solution infused into lateral cerebral ventricle will enter the CSF circulation and become widely distributed within the subarachnoid space of the whole brain, it is unlikely that the solution can penetrate the leptomeninges and diffuse into the parenchyma of the contralateral hemisphere (Stroobants et al., 2011; Zechariah et al., 2013). Therefore, it seems that the only way that a solute delivered to one hemisphere can pass to the other is by directly permeating through brain parenchyma. This means that the concentration of this solute will decrease with increasing distance from the infusion site. This decrease will be particularly obvious during the infusion of Ang-(1–7), as this solute is highly susceptible to cleavage by proteases and peptidases and thus has a relatively short half-life in the brain (Silva-Barcellos et al., 2001). Considering both these factors, diffusion distance and enzymic degradation, it is not surprising that the levels of Ang-(1–7) were not significantly increased in the contralateral hemisphere after infusion.

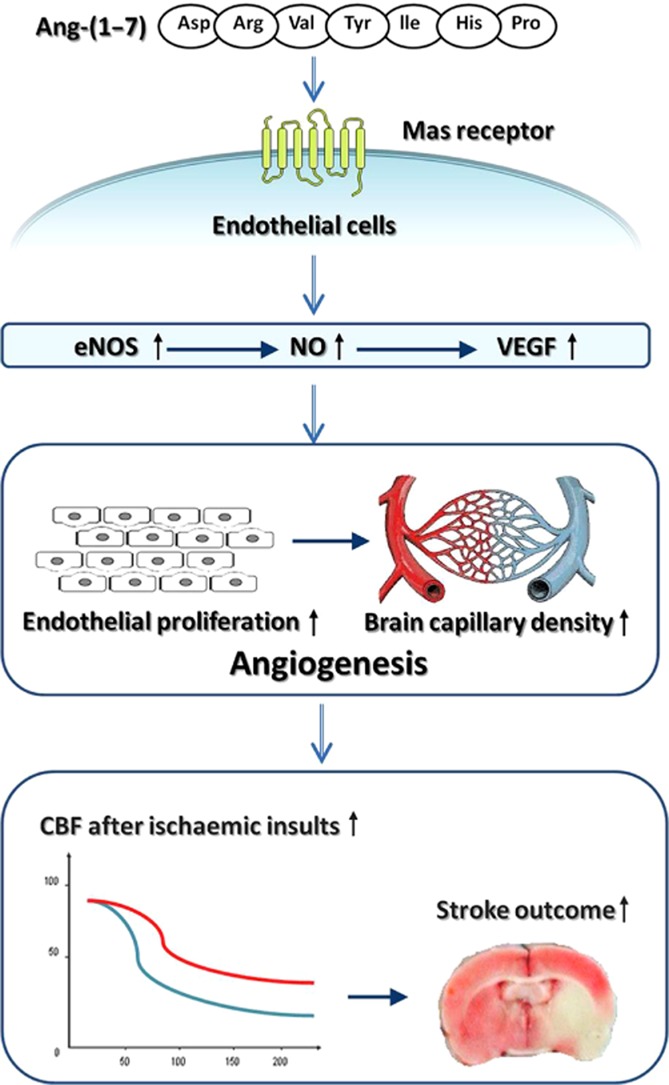

In conclusion, the present study provided the first evidence that infusion of Ang-(1–7) for 4 weeks promoted brain angiogenesis in a Mas/eNOS-dependent manner. More importantly, the Ang-(1–7)-induced angiogenesis attenuated the reduction of rCBF and improved stroke outcome during a subsequent ischaemic insult (Figure 6). These results demonstrate the role of Ang-(1–7) in brain angiogenesis and the underlying mechanisms. Moreover, our findings highlight brain Ang-(1–7)/Mas signalling as a potential target for prevention of ischaemic stroke. Further studies are warranted to investigate whether Ang-(1–7) induces angiogenesis and thus exerts beneficial effects on brain plasticity and long-term sensorimotor recovery after an ischaemic stroke.

Figure 6.

Diagram illustrating the mechanisms by which brain Ang-(1–7) promoted angiogenesis and induced tolerance against focal cerebral ischaemia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to L. T. (81171209, 81371406), J. T. Y. (81000544) and Y. D. Z. (81271418); grants from the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation to L. T. (ZR2011HZ001) and J. T. Y. (ZR2010HQ004); grants from the Medicine and Health Science Technology Development Project of Shandong Province to L. T. (2011WSA02018) and J. T. Y. (2011WSA02020); a grant from the Six Talent Summit of Jiangsu Province to Y. D. Z. (N02012-WS-086); and a grant from the Innovation Project for Postgraduates of Jiangsu Province to T. J. (CXLX13_561).

Glossary

- aCSF

artificial CSF

- Ang-(1–7)

angiotensin-(1–7)

- EdU

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

- eNOS

endothelial NOS

- L-NIO

N5-(1-iminoethyl)-L-ornithine

- pMCAO

permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion

- rCBF

regional cerebral blood flow

Author contributions

J.-T. Y., Y.-D. Z. and L. T. conceived and designed the experiments. T. J., X.-C. Z., H.-F. W. and M.-S. T. performed the experiments. Q.-Q. Z., L. C. and J. L. analysed the data. T. J. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.12770

Figure S1 Schematic illustration of the experimental protocols.

Figure S2 Effects of Ang-(1–7) infusion on mean arterial BP and brain Ang-(1–7) concentration. (A) Mean arterial BP of rat after 4 week infusion of Ang-(1–7) or vehicle (n = 12 per group). (B) Concentration of Ang-(1–7) in cerebral cortex and hippocampus of rat after 4 week infusion of Ang-(1–7) or vehicle (n = 6 per group). Bars: 100 μm. Data shown are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 significantly different from vehicle-treated rats.

Figure S3 Inhibition of endostatin on Ang-(1–7)-induced increase in brain capillary density. Capillary density in cerebral cortex of the ipsilateral hemisphere after co-treatment with endostatin was assessed by CD31 immunofluorescence staining. It should be noted that the data of the vehicle group were produced in response to a reviewer's comment, and were therefore not contemporaneous with the data of the other two groups. Data shown are means ± SD; n = 6 per group; *P < 0.05 significantly different from Ang-(1–7)-treated rats.

Table S1 Primary antibodies used in Western blot.

References

- Addo J, Ayerbe L, Mohan KM, Crichton S, Sheldenkar A, Chen R, et al. Socioeconomic status and stroke: an updated review. Stroke. 2012;43:1186–1191. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.639732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL. Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Xiao X, Chen S, Zhang C, Yi D, Shenoy V, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 priming enhances the function of endothelial progenitor cells and their therapeutic efficacy. Hypertension. 2013;61:681–689. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hashim AZ, Renno WM, Raghupathy R, Abduo HT, Akhtar S, Benter IF. Angiotensin-(1–7) inhibits allergic inflammation, via the MAS1 receptor, through suppression of ERK1/2- and NF-kappaB-dependent pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:1964–1976. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Xia H, Cai Y, Halabi CM, Becker LK, Santos RA, et al. Brain-selective overexpression of human angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 attenuates neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;106:373–382. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Jiang T, Guo J, Liu Y, Cui G, Gu L, et al. Inhibition of autophagy contributes to ischemic postconditioning-induced neuroprotection against focal cerebral ischemia in rats. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertz K, Priller J, Kronenberg G, Fink KB, Winter B, Schrock H, et al. Physical activity improves long-term stroke outcome via endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent augmentation of neovascularization and cerebral blood flow. Circ Res. 2006;99:1132–1140. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250175.14861.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison TC, Silasi G, Boyd JD, Murphy TH. Displacement of sensory maps and disorganization of motor cortex after targeted stroke in mice. Stroke. 2013;44:2300–2306. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooijmans CR, de Vries R, Leenaars M, Curfs J, Ritskes-Hoitinga M. Improving planning, design, reporting and scientific quality of animal experiments by using the Gold Standard Publication Checklist, in addition to the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1259–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Gao L, Guo J, Lu J, Wang Y, Zhang Y. Suppressing inflammation by inhibiting the NF-kappaB pathway contributes to the neuroprotective effect of angiotensin-(1–7) in rats with permanent cerebral ischaemia. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:1520–1532. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Gao L, Lu J, Zhang YD. ACE2-Ang-(1–7)-mas axis in brain: a potential target for prevention and treatment of ischemic stroke. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2013a;11:209–217. doi: 10.2174/1570159X11311020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Gao L, Shi J, Lu J, Wang Y, Zhang Y. Angiotensin-(1–7) modulates renin–angiotensin system associated with reducing oxidative stress and attenuating neuronal apoptosis in the brain of hypertensive rats. Pharmacol Res. 2013b;67:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Gao L, Zhu XC, Yu JT, Shi JQ, Tan MS, et al. Angiotensin-(1–7) inhibits autophagy in the brain of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Pharmacol Res. 2013c;71:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Yu JT, Zhu XC, Tan MS, Wang HF, Cao L, et al. Temsirolimus promotes autophagic clearance of amyloid-beta and provides protective effects in cellular and animal models of Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacol Res. 2014a;81:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Yu JT, Zhu XC, Wang HF, Tan MS, Cao L, et al. Acute metformin preconditioning confers neuroprotection against focal cerebral ischemia by pre-activation of AMPK-dependent autophagy. Br J Pharmacol. 2014b;171:3146–3157. doi: 10.1111/bph.12655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupinski J, Kaluza J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Wang JM. Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1994;25:1794–1798. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.9.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Mogi M, Iwanami J, Min LJ, Tsukuda K, Sakata A, et al. Temporary pretreatment with the angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, valsartan, prevents ischemic brain damage through an increase in capillary density. Stroke. 2008;39:2029–2036. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.503458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Kilkenny C, Wainwright CL. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecca AP, Regenhardt RW, O'Connor TE, Joseph JP, Raizada MK, Katovich MJ, et al. Cerebroprotection by angiotensin-(1–7) in endothelin-1-induced ischaemic stroke. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:1084–1096. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba T, Koike H, Murakami K, Aoki M, Makino H, Hashiya N, et al. Angiogenesis induced by endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene through vascular endothelial growth factor expression in a rat hindlimb ischemia model. Circulation. 2003;108:2250–2257. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093190.53478.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly MS, Boehm T, Shing Y, Fukai N, Vasios G, Lane WS, et al. Endostatin: an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell. 1997;88:277–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos-Silva DG, Verano-Braga T, Santos RA. Angiotensin-(1–7): beyond the cardio-renal actions. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;124:443–456. doi: 10.1042/CS20120461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regenhardt RW, Desland F, Mecca AP, Pioquinto DJ, Afzal A, Mocco J, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of angiotensin-(1–7) in ischemic stroke. Neuropharmacology. 2013a;71:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regenhardt RW, Mecca AP, Desland F, Ritucci-Chinni PF, Ludin JA, Greenstein D, et al. Centrally administered angiotensin-(1–7) increases the survival of stroke prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Exp Physiol. 2013b;99:442–453. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.075242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renno WM, Al-Banaw AG, George P, Abu-Ghefreh AA, Akhtar S, Benter IF. Angiotensin-(1–7) via the Mas receptor alleviates the diabetes-induced decrease in GFAP and GAP-43 immunoreactivity with concomitant reduction in the COX-2 in hippocampal formation: an immunohistochemical study. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2012;32:1323–1336. doi: 10.1007/s10571-012-9858-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio WO, Souza dos Santos RA, Faria-Silva R, da Mata Machado LT, Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. Angiotensin-(1–7) through receptor Mas mediates endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation via Akt-dependent pathways. Hypertension. 2007;49:185–192. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000251865.35728.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos RA, Simoes e Silva AC, Maric C, Silva DM, Machado RP, de Buhr I, et al. Angiotensin-(1–7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8258–8263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432869100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siamwala JH, Dias PM, Majumder S, Joshi MK, Sinkar VP, Banerjee G, et al. L-theanine promotes nitric oxide production in endothelial cells through eNOS phosphorylation. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Barcellos NM, Frezard F, Caligiorne S, Santos RA. Long-lasting cardiovascular effects of liposome-entrapped angiotensin-(1–7) at the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Hypertension. 2001;38:1266–1271. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.096056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes e Silva AC, Silveira KD, Ferreira AJ, Teixeira MM. ACE2, angiotensin-(1–7) and Mas receptor axis in inflammation and fibrosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:477–492. doi: 10.1111/bph.12159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroobants S, Gerlach D, Matthes F, Hartmann D, Fogh J, Gieselmann V, et al. Intracerebroventricular enzyme infusion corrects central nervous system pathology and dysfunction in a mouse model of metachromatic leukodystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2760–2769. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumners C, Horiuchi M, Widdop RE, McCarthy C, Unger T, Steckelings UM. Protective arms of the renin–angiotensin system in neurological disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40:580–588. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson RA, Morton MT, Tsao-Wu G, Savalos RA, Davidson C, Sharp FR. A semiautomated method for measuring brain infarct volume. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:290–293. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibeault S, Rautureau Y, Oubaha M, Faubert D, Wilkes BC, Delisle C, et al. S-nitrosylation of beta-catenin by eNOS-derived NO promotes VEGF-induced endothelial cell permeability. Mol Cell. 2010;39:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kilic E, Kilic U, Weber B, Bassetti CL, Marti HH, et al. VEGF overexpression induces post-ischaemic neuroprotection, but facilitates haemodynamic steal phenomena. Brain. 2005;128((Pt 1)):52–63. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Sriramula S, Lazartigues E. ACE2/ANG-(1–7)/Mas pathway in the brain: the axis of good. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R804–R817. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00222.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechariah A, ElAli A, Doeppner TR, Jin F, Hasan MR, Helfrich I, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes pericyte coverage of brain capillaries, improves cerebral blood flow during subsequent focal cerebral ischemia, and preserves the metabolic penumbra. Stroke. 2013;44:1690–1697. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C, Pan F, Jones LA, Lim MM, Griffin EA, Sheline YI, et al. Evaluation of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine staining as a sensitive and reliable method for studying cell proliferation in the adult nervous system. Brain Res. 2010;1319:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Wang L, Zhang L, Chen J, Zhu Z, Zhang Z, et al. Nitric oxide enhances angiogenesis via the synthesis of vascular endothelial growth factor and cGMP after stroke in the rat. Circ Res. 2003;92:308–313. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000056757.93432.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lu J, Shi J, Lin X, Dong J, Zhang S, et al. Central administration of angiotensin-(1–7) stimulates nitric oxide release and upregulates the endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression following focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats. Neuropeptides. 2008;42:593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Zhao T, Chen Y, Sun Y. Angiotensin 1–7 promotes cardiac angiogenesis following infarction. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2013 doi: 10.2174/15701611113119990006. doi: 10.3410/f.718007491.793476041; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Schematic illustration of the experimental protocols.

Figure S2 Effects of Ang-(1–7) infusion on mean arterial BP and brain Ang-(1–7) concentration. (A) Mean arterial BP of rat after 4 week infusion of Ang-(1–7) or vehicle (n = 12 per group). (B) Concentration of Ang-(1–7) in cerebral cortex and hippocampus of rat after 4 week infusion of Ang-(1–7) or vehicle (n = 6 per group). Bars: 100 μm. Data shown are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 significantly different from vehicle-treated rats.

Figure S3 Inhibition of endostatin on Ang-(1–7)-induced increase in brain capillary density. Capillary density in cerebral cortex of the ipsilateral hemisphere after co-treatment with endostatin was assessed by CD31 immunofluorescence staining. It should be noted that the data of the vehicle group were produced in response to a reviewer's comment, and were therefore not contemporaneous with the data of the other two groups. Data shown are means ± SD; n = 6 per group; *P < 0.05 significantly different from Ang-(1–7)-treated rats.

Table S1 Primary antibodies used in Western blot.