Abstract

Objectives

To examine patient and regional factors associated with the use of intensive medical procedures in the last six months of life.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

The Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a longitudinal nationally representative cohort of older adults.

Participants

3,069 HRS decedents aged 66 years or older.

Measurements

Multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate associations among patient and regional factors and receipt of five intensive procedures: intubation/mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, gastrostomy tube insertion, enteral/parenteral nutrition, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the last 6 months of life.

Results

Approximately 18% of subjects (n=546) underwent at least one intensive procedure in the last six months of life. Characteristics significantly associated with lower odds of an intensive procedure included age 85–94 years, compared to 65–74 years (Adjusted Odds Ratio 0.67, 95% Confidence Interval 0.51–0.90); Alzheimer’s disease (0.71, 0.54–0.94); cancer (0.60, 0.43–0.85); nursing home residence (0.70, 0.50–0.97); and having an advance directive (0.71, 0.57–0.89). In contrast, living in a region with higher hospital care intensity and black race both doubled one’s odds of undergoing an intensive procedure (2.16, 1.48–3.13, and 2.02, 1.52–2.69, respectively).

Conclusion

Both patient characteristics and regional practice patterns are important determinants of intensive procedure use in the last six months of life. The effect of non-clinical factors highlights the need to better align treatments with patient preferences.

Keywords: End-of-Life Decisions, Terminal Care, Intensive Care, Medicare

INTRODUCTION

Treatment for patients in the last year of life accounts for more than one-quarter of Medicare spending.1 However, the cost of end-of-life care varies significantly by region2 and it is not clear that more expensive or more intensive care leads to better outcomes.3–7 A variety of factors are associated with variations in end-of-life care, including regional and physician practice patterns; patient characteristics such as race, age, functional decline, and some chronic diseases; and patient preferences.8–20 Yet, rarely have these factors been examined simultaneously.

While researchers and policymakers often focus on the rising costs of health care, patients are more likely to express preferences in terms of specific life-sustaining treatments or invasive procedures (e.g., cardiopulmonary resuscitation) and the outcomes they may achieve21–23. Previous studies have examined the determinants of specific patient-centered outcomes, such as surgery,17 intensive care unit (ICU) use,18 and hospital days;19 other research has focused on the effect of specific variables, such as race and advanced directives, on the likelihood of undergoing one of many intensive procedures.8,15,16

To our knowledge, however, no study to date has simultaneously evaluated the impact of patients’ social, functional, and health characteristics, as well as regional factors and practice patterns, on the likelihood of undergoing one or more intensive procedures at the end of life. Concurrent investigation of both patient and regional determinants of treatment intensity is critical to efforts aiming to maximize health care value and ensure that treatment decisions are consistent with patient preferences. In this paper, we use a nationally representative cohort study of older adults to examine a more comprehensive set of patient and regional factors that may predict use of intensive procedures in the last six months of life.

METHODS

Data Sources

We sampled decedents from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative longitudinal cohort study of older adults in the United States. More than 30,000 subjects aged 50 years and older have enrolled in the study since 1992. The HRS conducts serial “core” interviews with participants every two years, with response rates for the 2002–2008 waves exceeding 86%.24 During each cycle, subjects who have died since the most recent core interview are identified, and interviews are conducted with a proxy who is knowledgeable about the deceased participant, usually a surviving spouse or adult child. A complete description of the HRS can be obtained at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu.

The HRS interviews capture a wide spectrum of data about each participant, including demographic, economic, social, and functional characteristics. Additionally, more than 80% of HRS participants have provided authorization for their responses to be merged with their individual Medicare claims.

Based on zip code of residence, we linked each HRS participant to a hospital referral region as defined bythe Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care.25 The Dartmouth Atlas database provides information about the supply of medical resources in each hospital referral region, including the number of acute-care hospital beds, the number of physicians and specialists, and a relative measure of local practice pattern intensity (the Hospital Care Intensity Index) that reflects both the average amount of time Medicare beneficiaries spend in hospitals and the intensity of physician services delivered during hospital stays.

Sample

We sampled HRS decedents aged 66 years and older for whom a proxy completed a post-death interview between 2002 and 2008 (n = 4665) and limited our sample to those with linked Medicare claims (n = 4048). Of note, HRS decedents with linked Medicare claims were on average older (82.8 versus 78.3 years), more likely to have completed a high school degree (58% versus 53%) and more likely to be non-Hispanic white (79% versus 64%). To ensure complete claims data during the 12 months prior to death, we excluded participants enrolled in managed care plans (n = 694), as well as individuals without continuous Part A and Part B Medicare coverage (n = 285). The final sample included 3,069 subjects.

Outcome Measure

Our primary outcome was the use of one or more intensive medical procedures in the last six months of life, as determined by a review of ICD-9 codes in each subject’s Medicare claims. We relied on the approach first piloted by Barnato et al, which identified six life-sustaining treatments as measures of intensive care based on the judgment of a multidisciplinary group of physicians and semi-structured interviews with over 100 informants.26 These procedures, which have since been adopted in other analyses of patterns of life-sustaining treatment,16 include intubation and mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, gastrostomy tube insertion, hemodialysis, enteral or parenteral nutrition, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Based on our clinical experience, we hypothesized that hemodialysis, which is routinely delivered in outpatient settings as maintenance therapy for end-stage renal disease, would have a significantly different pattern of associations and excluded it from the list of intensive medical procedures in our primary analysis. We also analyzed each procedure in isolation as a secondary outcome.

Independent Variables

We selected patient-level and regional variables that we hypothesized may be associated with the use of intensive procedures, based on a conceptual model of the determinants of treatment intensity among patients with serious illness.20 Extracted from participants’ final core interview (on average 13.7 months before death), patient-level variables included age, race and ethnicity, sex, educational level, marital status, net worth, religiosity, the presence of a relative living nearby, and residential status (nursing home or community dwelling). In the interest of parsimony, functional status was measured as a binary variable, indicating whether or not the participant required assistance with one or more basic activities of daily living (ADLs).27 A single variable extracted from the proxy interview after death was whether the subject had completed an advance directive.

In some cases (n = 467) the final core interview was conducted within the six months prior to death, such that a procedure could have occurred before the interview. To avoid potential reverse causality in these instances, we measured three variables (nursing home residence, the presence of a relative living nearby, and functional status) with the responses reported in the second-most-recent core interview, on average 28 months prior to death.

We identified chronic medical conditions by applying algorithms established by the Chronic Condition Data Warehouse to each participant’s Medicare claims between 6 and 12 months before death.28 This timeframe was selected to ensure that the identified medical conditions preceded, and therefore may have influenced, a patient’s course of treatment in his or her final six months. Additionally, we assessed the cumulative burden of each individual’s comorbidities for the same period using the Elixhauser Index,29 modified to include dementia diagnoses.

Regional predictor variables drawn from the Dartmouth Atlas included the number of acute-care hospital beds per 1,000 residents, the number of specialists per 100,000 residents, and the Hospital Care Intensity (HCI) Index, which is calculated as a standardized ratio between the average number of days patients in that hospital referral region spend in the hospital and the average number of physician encounters they experience during each hospital stay, as compared with the national average.25 We selected the HCI Index among several measures of regional care intensity (including others that focus on spending per patient) because we wanted to isolate the intensity of treatment provided in the inpatient setting, where intensive medical procedures usually occur.

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated summary statistics and frequency distributions for all variables. We used univariate logistic regression to test the unadjusted associations between each independent variable and the odds of undergoing one or more of the intensive procedures under study. Multivariable logistic regression was used to measure the independent relationships between intensive procedure use and each predictor variable, while controlling for all of the other factors in the primary model. We further limited the independent variables in the secondary models to include only those that had a significant relationship with our primary outcome or have been found to be associated with treatment intensity in other studies.10,19,30–32

We used multiple imputations (five cycles) to account for missing data. Missing data comprised less than 3% of data values, and were most frequent among functional status, nursing home residence, and the presence of a relative nearby. We used STATA 11 for all statistical analyses (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).33 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

RESULTS

A total of 3,069 HRS participants died during the study period and met our inclusion/exclusion criteria. Table 1 presents personal and regional characteristics of the study sample. On average, patients were 83.2 years old (median 84, SD 8.4) at the time of death. Just over half of the subjects (55.4%) were female and the majority was non-Hispanic white (80%). The most common chronic medical conditions among participants were ischemic heart disease (35.6%), congestive heart failure (31.2%), diabetes (29.4%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (28.3%).

Table 1.

Patient and Regional Characteristics

| Subject characteristicsa | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 83.2 (8.4) |

| Female, n (%) | 1700 (55.4) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic white, n (%) | 2466 (80.4) |

| Black, n (%) | 391 (12.7) |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 164 (5.3) |

| Other, n (%) | 48 (1.6) |

| Completed high school, n (%) | 1632 (57.9) |

| Married, n (%) | 1105 (39.1) |

| Net worth, median ($) | 89,500 |

| Nursing home resident, n (%) | 510 (18.3) |

| Religion is “very important”, n (%) | 1868 (66.1) |

| Relatives nearby, n (%) | 968 (35.1) |

| Discussed end-of-life care, n (%) | 1699 (55.5) |

| Advance directive, n (%) | 1948 (65.0) |

| Needs assistance with at least one ADLb, n (%) | 1072 (38.5) |

| Medicaid enrollment, n (%) | 631 (22.6) |

| Medigap enrollment, n (%) | 1392 (49.7) |

| Chronic medical conditions (6 to 12 months before death) | |

| Chronic Kidney Disease, n (%) | 474 (15.4) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, n (%) | 870 (28.3) |

| Congestive Heart Failure, n (%) | 957 (31.2) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 902 (29.4) |

| Hip fracture, n (%) | 124 (4.0) |

| Depression, n (%) | 389 (12.7) |

| Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack, n (%) | 465 (15.2) |

| Ischemic Heart Disease, n (%) | 1093 (35.6) |

| Alzheimer’s Disease, n (%) | 734 (23.9) |

| Cancerc, n (%) | 339 (11.0) |

| Comorbidity Scored, mean (SD) | 4.26 (3.0) |

| Regional factors | |

| Hospital Care Intensity (HCI) Index, mean (SD) | 1.02 (0.3) |

| Acute hospital beds per 1,000 residents, mean (SD) | 2.54 (0.5) |

| Specialists per 100,000 residents, mean (SD) | 123.9 (22.4) |

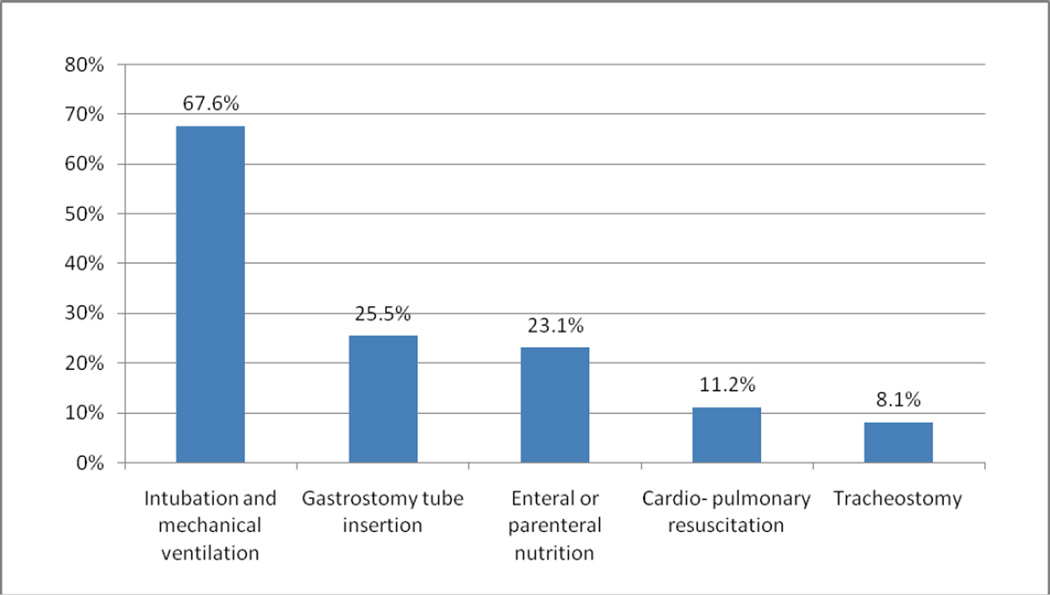

Five hundred forty-six (17.8%) subjects received at least one of the five intensive procedures under study (intubation and mechanical ventilation, gastrostomy tube insertion, enteral or parenteral nutrition, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or tracheostomy) in the last six months of life, and 159 patients (5.2%) had two or more intensive procedures. Of those who underwent at least one intensive procedure, 432 (79%) had an intensive procedure in the final month of life. Figure 1 displays the frequency of each intensive procedure among those who had at least one procedure. More than two-thirds (67.6%) of these subjects underwent intubation and mechanical ventilation, while approximately one quarter (25.5%) had a gastrostomy tube placed.

Figure 1.

Intensive Procedure Use Among Those Undergoing at Least One Procedure, n=546

Table 2 reports the results of the unadjusted and adjusted analyses of factors associated with undergoing an intensive procedure in the last six months of life. Holding other factors equal, older patients—those in the 85–94 and 95+ categories—were less likely to undergo an intensive procedure in the last six months of life (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 0.67 [95% Confidence Interval (CI) 0.51 to 0.90] and AOR 0.55 [CI 0.35 to 0.85], respectively). Other patient factors independently associated with decreased likelihood of intensive procedure use were having an advance directive (AOR 0.71 [CI 0.57 to 0.89]) and residing in a nursing home (AOR 0.70 [CI 0.50 to 0.97]). Black race, on the other hand, was associated with twice the odds of an intensive procedure (AOR 2.02 [CI 1.52 to 2.69]). Hispanic ethnicity was also associated with intensive procedure use (AOR 1.53 [CI 1.00 to 2.34]), although the relationship bordered on the margin of significance.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds of Intensive Procedure Use in the Last Six Months of Life

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Subject characteristics | ||

| Age (reference = 74 or younger) | ||

| 75–84 | 1.15 (0.95 – 1.39) | 0.82 (0.64 – 1.07) |

| 85–94 | 0.69 (0.57 – 0.85) | 0.67 (0.51 – 0.90) |

| 95+ | 0.63 (0.43 – 0.91) | 0.55 (0.35 – 0.85) |

| Female | 0.87 (0.72 – 1.05) | 0.91 (0.73 – 1.13) |

| Race (reference = non-Hispanic white) | ||

| Black | 2.21 (1.73 – 2.80) | 2.02 (1.52 – 2.69) |

| Hispanic | 1.94 (1.36 – 2.75) | 1.53 (1.00 – 2.34) |

| Other | 1.73 (0.91 – 3.30) | 2.04 (1.03 – 4.02) |

| Completed high school | 0.83 (0.69 – 1.00) | 1.01 (0.81 – 1.26) |

| Married | 1.12 (0.92 – 1.36) | 0.95 (0.75 – 1.21) |

| Net worth (reference = lower quartile) | ||

| Second quartile (≥$9,300, <$89.500) | 1.05 (0.84 – 1.31) | 0.99 (0.74 – 1.33) |

| Third quartile (≥$89,500, <$264,000) | 0.93 (0.74 – 1.16) | 1.11 (0.81 – 1.53) |

| Upper quartile (≥$264,000) | 0.95 (0.76 – 1.17) | 1.21 (0.88 – 1.68) |

| Nursing home resident | 0.55 (0.42 – 0.73) | 0.70 (0.50 – 0.97) |

| Religion is “very important” | 1.04 (0.85 – 1.27) | 0.95 (0.76 – 1.17) |

| Relatives nearby | 0.91 (0.74 – 1.12) | 0.89 (0.72 – 1.09) |

| Advance directive | 0.52 (0.43 – 0.63) | 0.71 (0.57 – 0.89) |

| Needs assistance with at least one ADLa | 0.74 (0.61 – 0.91) | 0.89 (0.70 – 1.12) |

| Chronic medical conditions (6 to 12 months before death) | ||

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 1.39 (1.09 – 1.77) | 1.08 (0.82 – 1.44) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 1.13 (0.92 – 1.38) | 0.96 (0.76 – 1.21) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1.22 (1.00 – 1.49) | 1.07 (0.84 – 1.38) |

| Diabetes | 1.41 (1.16 – 1.72) | 1.03 (0.82 – 1.30) |

| Hip fracture | 0.63 (0.36 – 1.08) | 0.76 (0.43 – 1.34) |

| Depression | 1.10 (0.84 – 1.44) | 1.12 (0.82 – 1.53) |

| Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack | 1.13 (0.88 – 1.45) | 1.06 (0.80 – 1.40) |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 1.29 (1.07 – 1.56) | 1.10 (0.88 – 1.38) |

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 0.68 (0.54 – 0.86) | 0.71 (0.54 – 0.94) |

| Cancerb | 0.72 (0.52 – 0.99) | 0.60 (0.43 – 0.85) |

| Comorbidity Scorec | 1.05 (1.02 – 1.08) | 1.04 (0.99 – 1.10) |

| Regional factors | ||

| Hospital Care Intensity (HCI) Index | 2.95 (2.18 – 4.00) | 2.16 (1.48 – 3.13) |

| Acute hospital beds per 1,000 residents | 1.36 (1.14 – 1.62) | 1.18 (0.96 – 1.44) |

| Specialists per 100,000 residents | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.01) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.01) |

Two chronic medical conditions—Alzheimer’s disease and cancer—were associated with decreased odds of undergoing an intensive procedure (AOR 0.71 [CI 0.54 to 0.94] and AOR 0.60 [CI 0.43 to 0.85], respectively). While we found a statistically significant relationship between the total number of comorbidities and intensive procedures in our unadjusted analysis (OR 1.05 [CI 1.02 to 1.08]), this association did not reach statistical significance in the adjusted model (AOR 1.04 [CI 0.99 to 1.10]).

Among regional factors, residing in a hospital referral region with a higher Hospital Care Intensity (HCI) Index was strongly associated with an increased likelihood of undergoing an intensive procedure (AOR 2.16 [CI 1.48 to 3.13]). For instance, an individual in Miami, FL (a region with HCI Index 1.78) would have 28% probability of undergoing an intensive procedure, compared with only 12% probability in Rochester MN (HCI Index 0.64), all other factors held equal. The number of specialists and acute hospital beds per capita did not confer significantly increased odds of undergoing an intensive procedure in our adjusted analysis.

Table 3 reports the factors associated with each intensive procedure considered as a separate outcome. While these analyses are somewhat limited by sample size, the following patterns of results are notable. HCI Index was associated with increased odds of all five individual intensive procedures. The associations of older age and nursing home residence with reduced odds of the combined intensive procedures outcome were mirrored in the analysis of intubation and mechanical ventilation in isolation. Black race was associated with increased odds of both intubation and gastrostomy tube insertion, whereas Hispanic ethnicity was associated with increased odds of gastrostomy tube insertion only. Having an advance directive was associated with decreased odds of intubation and CPR, but not the three other procedures under study.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds of Individual Procedure Use in the Last Six Months of Life (to be included as electronic supplement)

| Intubation and mechanical ventilation |

Gastrostomy tube insertion |

Enteral or parenteral nutrition |

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

Tracheostomy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects undergoing procedure | 369 | 139 | 126 | 61 | 44 |

| Subject characteristics | |||||

| Age (reference = 74 or younger) | |||||

| 75–84 | 0.82 (0.62 – 1.10) | 1.22 (0.72 – 2.06) | 0.71 (0.42 – 1.21) | 0.72 (0.37 – 1.38) | 0.80 (0.38 – 1.67) |

| 85–94 | 0.58 (0.42 – 0.80) | 1.42 (0.82 – 2.43) | 0.88 (0.52 – 1.50) | 0.74 (0.37 – 1.51) | 0.44 (0.18 – 1.07) |

| 95+ | 0.39 (0.22 – 0.70) | 1.00 (0.45 – 2.26) | 0.68 (0.31 – 1.49) | 0.31 (0.07 – 1.43) | N/Aa |

| Female | 0.87 (0.69 – 1.11) | 0.79 (0.54 – 1.15) | 1.24 (0.83 – 1.84) | 0.76 (0.44 – 1.32) | 0.72 (0.38 – 1.37) |

| Race (reference = non-Hispanic white) | |||||

| Black | 1.62 (1.18 – 2.22) | 2.85 (1.77 – 4.58) | 1.42 (0.85 – 2.38) | 1.66 (0.84 – 3.27) | 2.16 (0.94 – 4.96) |

| Hispanic | 0.95 (0.57 – 1.58) | 3.41 (1.83 – 6.36) | 1.80 (0.89 – 3.65) | 0.73 (0.23 – 2.25) | 2.01 (0.67 – 6.01) |

| Other | 1.48 (0.66 – 3.34) | 2.11 (0.63 – 7.06) | 2.14 (0.73 – 6.31) | 1.92 (0.42 – 8.66) | 1.56 (0.19 – 13.02) |

| Nursing home resident | 0.58 (0.38 – 0.88) | 0.72 (0.39 – 1.31) | 0.97 (0.56 – 1.69) | 0.46 (0.16 – 1.31) | 0.16 (0.02 – 1.08) |

| Religion is “very important” | 1.14 (0.88 – 1.48) | 0.73 (0.50 – 1.08) | 1.02 (0.67 – 1.56) | 0.81 (0.45 – 1.46) | 1.12 (0.51 – 2.43) |

| Relatives nearby | 0.85 (0.67 – 1.09) | 0.75 (0.48 – 1.17) | 0.99 (0.68 – 1.45) | 0.94 (0.54 – 1.64) | 1.48 (0.78 – 2.81) |

| Advance directive | 0.66 (0.51 – 0.85) | 1.02 (0.68 – 1.52) | 0.81 (0.54 – 1.22) | 0.41 (0.23 – 0.74) | 0.93 (0.45 – 1.92) |

| Needs assistance with at least one ADLb | 0.78 (0.58 – 1.03) | 1.30 (0.83 – 2.03) | 1.42 (0.92 – 2.21) | 1.11 (0.59 – 2.08) | 1.29 (0.60 – 2.75) |

| Regional factors | |||||

| Hospital Care Intensity (HCI) Index | 2.25 (1.45 – 3.49) | 2.04 (1.07 – 3.89) | 2.50 (1.28 – 4.88) | 3.33 (1.28 – 8.66) | 8.04 (2.79 – 23.20) |

| Acute hospital beds per 1,000 residents | 1.13 (0.89 – 1.43) | 1.37 (0.97 – 1.95) | 1.27 (0.87 – 1.85) | 0.82 (0.47 – 1.43) | 0.77 (0.39 – 1.54) |

| Specialists per 100,000 residents | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.01) | 1.01 (1.01 – 1.02) | 0.99 (0.98 – 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.02) |

Note: Bold indicates statistical significance at p<0.05. Models also adjusted for: chronic kidney disease, COPD, CHF, diabetes, hip fracture, depression, stroke or transient ischemic attack, ischemic heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer and comorbidity score.

No individuals in the 95+ category had a tracheostomy

Activity of Daily Living27

DISCUSSION

We combined rich longitudinal survey data with regional characteristics and individual Medicare claims in order to advance our understanding of the factors associated with the use of intensive medical procedures in the last six months of life. Most importantly, we found that regional health care intensity has a strong independent effect on the medical care that patients receive at the end of life, even after controlling for individual medical, social, and functional characteristics. In particular, we found that the odds of undergoing an intensive procedure in the last six months of life are significantly higher among patients who reside in regions with a high Hospital Care Intensity Index. The HCI Index is a proxy measure of regional practice patterns and thus conceptually captures both supply factors and local medical culture and practice norms. As noted in the example above, our findings suggest that a person in Miami, FL would have more than double the probability of undergoing an intensive procedure at the end of life than if she were living in Rochester, MN, all other factors held equal.

Over the last decade, regional variation in medical care has been a frequent topic in the medical literature, and increasing attention has focused on differences in the end-of-life care that patients receive. The Dartmouth Atlas, for instance, has found that the likelihood of a patient with advanced cancer dying in the hospital varies from 13% to 50% depending on the medical center at which she is receiving care.34 Others have documented that the probability of dialysis discontinuation prior to death among patients with end-stage renal disease varies from as low as 17% to as high as 40% in different parts of the country.35 Surrounding this literature has been a long-standing debate as to whether regional variation in treatment intensity really reflects local practice patterns or is instead rooted in confounding and perhaps unobserved patient factors.8,18,36–40 Our research, which controls for many of these potential confounders, makes a strong case that the care patients receive at the end of life is indeed influenced by where they live. It is worth noting that the association we observed between intensive procedure use and the HCI Index was not mirrored for the number of hospital beds or specialists per capita, our two regional measures of health care supply. This may be because the HCI Index is collinear with these supply factors or because the HCI Index also captures the harder to measure construct of practice culture.

Previous studies have found that black race and Hispanic ethnicity are strongly associated with higher expenditures8,10 and the use of some intensive procedures8,15 at the end of life. Consistent with this literature, we found that black race more than doubles the odds of receiving an intensive procedure in the last six months of life. Interestingly, while Hispanic ethnicity bordered the margin of statistical significance in our primary analysis, it was associated with three-fold higher odds of undergoing gastrostomy tube placement when this procedure was considered alone. Some studies have questioned whether race may be a proxy for other determinants of care intensity, such as urban residence.15 Our model including patient and regional factors together suggests that regional characteristics do not mediate this relationship and that race continues to have a strong independent association with the care that patients receive at the end of life.

Previous evidence has been mixed on whether advance directives are associated with a reduction in the use of life-sustaining treatments.10,16,41,42 In this analysis, we found that the presence of an advance directive reduced one’s odds of undergoing an intensive procedure by about 30%. In contrast to some prior studies, we considered a wide array of patient and regional variables and included all advance directives, not just those specifying limitations in treatment. Interestingly, when considering the intensive procedures independently, the presence of an advance directive was only associated with decreased odds of intubation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation—precisely the procedures that are most likely to be included in living wills and advance care planning documentation. This highlights the need to move beyond advance directives with “Do Not Resuscitate/Do Not Intubate” checkboxes to broader discussion and documentation of patients’ goals of care and values that could guide treatment decisions in a wider array of clinical scenarios.

There are several limitations to this study. We used a decedent-only sample and thereby artificially removed the prognostic uncertainty faced by seriously ill patients, their families and physicians.43 We recognize that for some seriously ill patients who may be near the end of life, intensive procedures are very appropriate. Yet, with these data we are unable to assess whether the intensive procedures received by the participants in our sample were consistent (or inconsistent) with their preferences and goals of care. Another limitation is that we analyzed patient deaths between 2000 and 2008 (the latest data available), but acknowledge that practice patterns may have evolved in the intervening years. Finally, our measures of functional status were limited to survey responses that were collected on average 20 months prior to death. While declining function in the years prior to death may be an important factor in treatment decisions, our results cannot account for the changes in functional status that often occur in the last months of life.

In conclusion, both patient and regional factors impact one’s likelihood of undergoing an intensive procedure in the last six months of life. By recognizing these factors, clinicians can work more effectively to ensure the treatment provided to patients with serious illness is in line with their individual preferences. Most importantly, by confirming that regional factors exert a real and independent influence on the care that patients receive at the end of life, this study reinforces the need to investigate the causes of disparate practice patterns and develop models of care that prioritize patients’ values and goals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding sources: This work was supported by the Medical Student Training in Aging Research (MSTAR) Program, The American Federation for Aging Research and National Institute on Aging (1K23AG040774-01A1).

Footnotes

Presentations: This work was presented as a poster at the American Geriatrics Society Annual Scientific Meeting in May 2013.

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no financial or personal conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and the preparation of the manuscript. Tschirhart and Kelley: Study concept and design. Du and Kelley: Acquisition of data.

Sponsor’s Role: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the research; the management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Riley GF, Lubitz JD. Long-term trends in medicare payments in the last year of life. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:565–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inpatient spending per decedent during the last six months of life, by race and level of care intensity. [Accessed July 25, 2012];Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, et al. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: The content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, et al. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: Health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:288–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wennberg JE, Bronner K, Skinner JS, et al. Inpatient care intensity and patients' ratings of their hospital experiences. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:103–112. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasaitis L, Fisher ES, Skinner JS, et al. Hospital quality and intensity of spending: Is there an association? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:566–572. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries' quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.184. Suppl Web Exclusives:W4-184-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: Why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:493–501. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larochelle MR, Rodriguez KL, Arnold RM, et al. Hospital staff attributions of the causes of physician variation in end-of-life treatment intensity. Palliat Med. 2009;23:460–470. doi: 10.1177/0269216309103664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, et al. Determinants of medical expenditures in the last 6 months of life. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:235–242. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levinsky NG, Yu W, Ash A, et al. Influence of age on medicare expenditures and medical care in the last year of life. JAMA. 2001;286:1349–1355. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinley ED, Garrett JM, Evans AT, et al. Differences in end-of-life decision making among black and white ambulatory cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:651–656. doi: 10.1007/BF02600155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Brien LA, Grisso JA, Maislin G, et al. Nursing home residents' preferences for life-sustaining treatments. JAMA. 1995;274:1775–1779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrett JM, Harris RP, Norburn JK, et al. Life-sustaining treatments during terminal illness: Who wants what? J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:361–368. doi: 10.1007/BF02600073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnato AE, Chang CC, Saynina O, et al. Influence of race on inpatient treatment intensity at the end of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:338–345. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0088-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Regional variation in the association between advance directives and end-of-life medicare expenditures. JAMA. 2011;306:1447–1453. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwok AC, Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, et al. The intensity and variation of surgical care at the end of life: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1408–1413. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnato AE, Berhane Z, Weissfeld LA, et al. Racial variation in end-of-life intensive care use: A race or hospital effect? Health Serv Res. 2006;41:2219–2237. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, et al. Disability and decline in physical function associated with hospital use at end of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:794–800. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2013-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley AS, Morrison RS, Wenger NS, et al. Determinants of treatment intensity for patients with serious illness: A new conceptual framework. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:807–813. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) paradigm. [Accessed March 26, 2013]; Available at: http://www.polst.org. [Google Scholar]

- 22.New York State Department of Health. Medical order for life-sustaining treatment (MOLST) - DOH-5003. [Accessed March 26, 2013]; Available at: http://www.health.ny.gov/forms/doh-5003.pdf.

- 23.Aging with dignity five wishes. [Accessed March 26, 2013]; Available at: http://www.agingwithdignity.org/five-wishes.php. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health and Retirement Study: Sample sizes and response rates. [Accessed August 3, 2012]; Available at: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/sampleresponse.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. [Accessed August 3, 2012]; Available at: www.dartmouthatlas.org. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnato AE, Farrell MH, Chang CC, et al. Development and validation of hospital "end-of-life" treatment intensity measures. Med Care. 2009;47:1098–1105. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181993191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chronic Condition Data Warehouse User Manual, Version 1.5. Buccaneer Computer Systems and Services. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:1140–1147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.True G, Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, et al. Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: The role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:174–179. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bülow H, Sprung CL, Baras M, et al. Are religion and religiosity important to end-of-life decisions and patient autonomy in the ICU? The Ethicatt Study. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1126–1133. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodman D, Morden N, Chang C, et al. Trends in cancer care near the end of life: A Dartmouth Atlas health care brief. 2013 Sep 4; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gessert CE, Haller IV, Johnson BP. Regional variation in care at the end of life: Discontinuation of dialysis. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-39. 39-2318-13-39.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bach PB. A map to bad policy--hospital efficiency measures in the dartmouth atlas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:569–573. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0909947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baicker K, Chandra A, Skinner JS, et al. Who you are and where you live: How race and geography affect the treatment of medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.33. Suppl Variation:VAR33-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in medicare services. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1465–1468. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1302981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skinner J, Staiger D, Fisher ES. Looking back, moving forward. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:569–574. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newhouse JP, Garber AM, Graham RP, et al. Variation in health care spending: Target decision making, not geography. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor JS, Heyland DK, Taylor SJ. How advance directives affect hospital resource use. Systematic review of the literature. Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:2408–2413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teno J, Lynn J, Wenger N, et al. Advance directives for seriously ill hospitalized patients: Effectiveness with the patient self-determination act and the SUPPORT intervention. SUPPORT investigators. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:500–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bach PB, Schrag D, Begg CB. Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: A study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA. 2004;292:2765–2770. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]