Abstract

Introduction: Individuals with neuropathic pain, angiokeratoma (AK) and/or cornea verticillata (CV) may be tested for Fabry disease (FD). Classical FD is characterised by a specific pattern of these features. When a patient presents with a non-specific pattern, the pathogenicity of a variant in the α-galactosidase A (GLA) gene may be unclear. This uncertainty often leads to considerable distress and inappropriate counselling and treatment. We developed a clinical approach for these individuals with an uncertain diagnosis of FD.

Materials and Methods: A document was presented to an FD expert panel with background information based on clinical experience and the literature, followed by an online survey and a written recommendation.

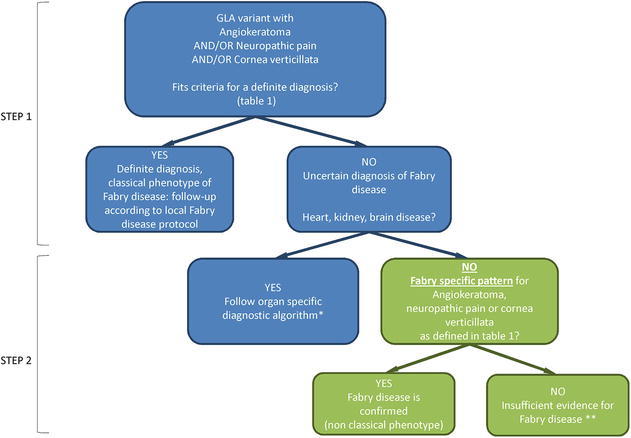

Results: The 13 experts agreed that the recommendation is intended for individuals with neuropathic pain, AK and/or CV only, i.e. without kidney, heart or brain disease, with an uncertain diagnosis of FD. Only in the presence of FD-specific neuropathic pain (small fibre neuropathy with FD-specific pattern), AK (FD-specific localisations) or CV (without CV inducing medication), FD is confirmed. When these features have a non-specific pattern, there is insufficient evidence for FD. If no alternative diagnosis is found, follow-up is recommended.

Conclusions: In individuals with an uncertain diagnosis of FD, the presence of an FD-specific pattern of CV, AK or neuropathic pain is sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of FD. When these features are non-specific, a definite diagnosis cannot (yet) be established and follow-up is indicated. ERT should be considered only in those patients with a confirmed diagnosis of FD.

Introduction

Fabry disease (OMIM 301500; FD) is an X-linked multisystem lysosomal storage disorder caused by deficient activity of α-galactosidase A (αGalA, E.C. 3.2.1.22). The estimated birth prevalence has originally been reported to be between 1:40.000 and 170.000 (Meikle et al. 1999; Poorthuis et al. 1999; Desnick et al. 2007). More than 600 variants/mutations in the α-galactosidase A (GLA) gene have been described (Garman 2007; HGMD 2014), most of which are private variants/mutations. For consistency, the term “variant” will be used throughout this article for all variations in the GLA gene, being either pathogenic, nonpathogenic or a genetic variant of unknown significance (GVUS); in the latter, an individual has an uncertain diagnosis of FD.

Fabry disease is generally divided into “classical” and “nonclassical” phenotypes. The first phenotype is usually characterised by a specific pattern of neuropathic pain (related to small fibre neuropathy, SFN), angiokeratoma and cornea verticillata (CV), while some or all of these features are usually absent in the latter (Elleder et al. 1990; Nakao et al. 1995). For definitions, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria for a definite diagnosis of FD, classical (Smid 2014) with permission for reprint

| A definite diagnosis of classical FD | |

| Male | Female |

| A variant in the GLA gene | |

| And | And |

| Severely decreased or absent leukocyte AGAL activity (<5% of the normal mean) combined with a minimum of 1 of the following criteria:a | A minimum of 1 of the following criteria: |

| Fabry neuropathic pain, cornea verticillata, angiokeratoma, increased plasma lysoGb3 or Gb3 in the range of “classical” FD males | Fabry neuropathic pain, cornea verticillata, angiokeratoma, increased plasma (lyso)Gb3 in the range of “classical” FD males |

| Or | Or |

| An affected family member with a definite diagnosis according to the criteria above | An affected family member with a definite diagnosis according to the criteria above |

| Uncertain FD diagnosis | |

| The individual does not fit the criteria for a definite diagnosis of classical FD. Further evaluations are needed, following the diagnostic algorithm | |

| Gold standard | |

| The gold standard for a diagnosis of FD in patients with an uncertain FD diagnosis, a GVUS and a non-specific FD sign is the demonstration of characteristic storage of the affected organ (e.g. heart, kidney, aside from skin) by electron microscopy analysis, according to the judgment of an expert pathologist | |

This definition was made to select those patients in whom there is no doubt that FD is present. If this definition is not met, FD cannot be ruled out, but further evaluation is needed to avoid labelling this individual with the wrong diagnosis

a Definitions:

Fabry neuropathic pain fits the “FD-specific criteria” if there is neuropathic pain related to small fibre neuropathy in hands and/or feet, starting before age 18 or increasing with heat, fever. Quantitative sensory testing (QST) reveals a decreased cold detection threshold and the intraepidermal nerve fibre density (IENFD) is decreased. There is no other cause for Fabry neuropathic pain

Angiokeratomas fit the “FD-specific criteria” if they are clustered and present in characteristic areas: bathing trunk area, lips and umbilicus. There is no other cause for angiokeratoma

Cornea verticillata fits the “FD-specific criteria” if there is a whorl-like pattern of corneal opacities. There is no other cause (medication induced, among others, amiodarone, chloroquine)

Since the availability of enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with recombinant human α-galactosidase A (agalsidase alpha, Shire HGT and agalsidase beta, Genzyme Corp., a Sanofi company), an increasing number of screening studies in high-risk populations as well as newborn screening studies have been performed (e.g. Bekri et al. 2005; Spada et al. 2006; Brouns et al. 2007; Lin et al. 2009; Wallin et al. 2011; Dubuc et al. 2012; Mechtler et al. 2012). These screening studies have revealed a high number of individuals with variants in the GLA gene (Kobayashi et al. 2012; Terryn et al. 2013; van der Tol et al. 2014). While the pathogenicity of some GLA variants is well described, the subjects identified by these screening studies often have a GVUS in the GLA gene, i.e. an uncertain diagnosis of FD. Interestingly, most male patients with a GVUS demonstrate residual enzyme activity, in contrast to the absent or near absent enzyme activity in classically affected males. Also, previous studies have shown that patients with a nonclassical phenotype often only show a slight increase of lysoGb3 in plasma, while classically affected males invariably have very high levels (Aerts et al. 2008; Rombach et al. 2010; Gold et al. 2013; Lukas et al. 2013).

The reason to test for FD is usually a non-specific symptom such as stroke, chronic kidney disease or left ventricular hypertrophy in the absence of other causes. However, individuals with neuropathic pain, angiokeratoma or CV – in the absence of symptomatic involvement of the heart, brain or kidney – may also be tested for the presence of a variant in the GLA gene. These solitary features may be present in a pattern that differs from what is usually seen in FD patients with a classical phenotype and is therefore considered non-specific. For example, angiokeratoma may be scattered instead of clustered, or neuropathic pain may not be related to an SFN and have started at a much older age than expected in the context of a classical FD phenotype. CV may be present in individuals who used medication that may induce CV. If in such an individual a variant in the GLA gene is found, while there is residual enzyme activity (for males) and normal or only slightly increased Gb3 and lysoGb3, the pathogenicity of this variant is generally unclear; the variant is a GVUS. The subsequent uncertain diagnosis may cause considerable distress for the patient and the family and may also lead to inappropriate counselling and initiation of treatment with expensive enzyme replacement therapy. Thus, it is of great importance to achieve a correct diagnosis.

To address diagnostic dilemmas with regard to FD, we initiated “The Hamlet study: Fabry or not Fabry” to valorise clinical and laboratory assessments in order to improve the diagnosis of FD [Dutch trial register www.trialregister.nl NTR3840 and NTR3841]. For individuals with an uncertain diagnosis of FD, diagnostic algorithms are developed based upon literature data and international expert consensus through a modified Delphi procedure. As part of this study, we developed the approach to aid in the diagnostic pathway, counselling and follow-up for individuals with an uncertain diagnosis of FD, who present with cornea verticillata, angiokeratoma or neuropathic pain, with a GVUS in the GLA gene, but without a classical FD phenotype (for definitions, see Table 1). The approach is based on the current available evidence and international consensus.

Materials and Methods

Panel and Delphi Procedure

FD experts were invited to participate in the study panel through email. A consensus document was compiled and presented to the experts with an explanation of the rationale of the study as well as literature references and the applicable adopted results from the previous consensus procedure on general diagnostic criteria for FD; see Table 1.

The modified Delphi procedure consisted of an online survey round (round 1), after which a written recommendation was created for review by the panel (round 2). In round 1, virtual case histories were presented with neuropathic pain, angiokeratoma and/or CV. These case histories contained information on clinical symptoms and biochemical findings (enzyme activity in leukocytes, Gb3 and lysoGb3) were given. The panellists were asked to indicate whether or not the available information was sufficient to confirm or reject FD in the particular case on a 5-point Likert scale and were invited to add comments and suggestions. Anonymised results were presented to the panel (absolute scores and comments) after round 1. Clarification and additional data were provided. The consensus document for round 2 that was subsequently created represented the opinion of the expert panel as assessed in round 1. This document was thereafter reviewed and discussed by the expert panel via personal communication. A final version was drafted, and all participants agreed on the recommendations presented herein.

Adopted Definitions

The criteria for a definite and an uncertain diagnosis of FD were adopted from a previous consensus procedure; see Table 1 (Smid 2014). Strict definitions of the FD-specific clinical features (neuropathic pain, angiokeratoma, CV) were applied. If these strict definitions are fulfilled, the specificity for FD is very high (i.e. there is no differential diagnosis). These criteria were created to select classical FD patients in whom there is no doubt about the diagnosis.

Results/Recommendations

See Fig. 1 for the diagnostic algorithm that was constructed based on the following results.

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic algorithm. Green: individuals with a GLA GVUS (uncertain diagnosis of FD) with angiokeratoma, SFN or cornea verticillata without heart, kidney or brain disease, the subjects of the current study. Step 1: apply criteria for a definite diagnosis, Table 1. Step 2: approach to individuals with an uncertain diagnosis of FD. *Organ-specific algorithm will be published in separate articles (Smid 2014; Van der Tol 2014a, b). **Follow-up in an expert centre for FD could be considered; ERT is not (yet) indicated

Panel

Thirteen FD experts were invited and consented to participate. The panel consisted of four general FD specialists in internal medicine (RL, GL, DC, MJ), two paediatricians (FW, UR), two neurologists (CS, AM), a cardiologist (FW), three nephrologists (ES, CT (paediatric nephrologist), MW) and a medical geneticist (GH).

The panel agreed on the following 2-step approach:

Step 1: An Individual with a GLA Variant, First Evaluation (Adopted from (Smid 2014))

The panel agreed that all individuals with a GLA mutation need to undergo a full assessment of all organ systems that are involved in FD, and extensive biochemical analyses should be pursued, including αGalA enzyme activity in leukocytes, plasma lysoGb3 (if available), plasma Gb3 and urine Gb3. The presence of Fabry-specific neuropathic pain, AK and/or CV should be thoroughly assessed. A complete family history should be taken. An expert on FD should interpret clinical and biochemical assessments. The criteria to identify the patient with a definite diagnosis of FD can subsequently be applied (Table 1).

Step 2: An Individual with a GLA Variant and an Uncertain Diagnosis of FD (i.e. He or she has a GVUS in the GLA gene)

If heart, kidney or brain disease is present, the respective organ-specific algorithm – developed in separate projects as part of the Hamlet study – should be applied. For these algorithms, left ventricular hypertrophy, chronic kidney disease and stroke/TIA are defined according to internationally accepted definitions. For example, kidney disease is defined as chronic kidney disease according to the 2012 international guideline for kidney disease (KDIGO, http://kdigo.org/home/guidelines/ckd-evaluation-management/), with a GFR and urinary protein excretion as measures of kidney disease (Van der Tol 2014a). In individuals who present with neuropathic pain, AK or CV, but in whom heart, kidney or brain involvement is absent, the panel agreed on the following:

Cornea Verticillata

In an individual who presents with cornea verticillata, in the absence of medication use that may induce cornea verticillata (Table 2), and in whom a GLA variant is found, there are no known alternative diagnoses but FD.

Table 2.

Medication that may induce cornea verticillata (for review on drug-induced corneal complications, see Hollander and Aldave (2004))

| Medication that may induce cornea verticillata | Comment |

|---|---|

| Amiodarone | Well documented to induce cornea Verticillata |

| Aminoquinolines (chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, amodiaquine) | Limited evidence, mainly case reports |

| Atovaquone | – |

| Clofazimine | – |

| Gentamicin (subconjunctival) | – |

| Gold | – |

| Mepacrine | – |

| Monobenzone (topical skin ointment) | – |

| NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen, indomethacin) | – |

| Perhexiline maleate | – |

| Phenothiazines | – |

| Suramin | – |

| Tamoxifen | – |

| Tilorone hydrochloride | – |

However, in an individual who presents with cornea verticillata only but who has used medication that may induce cornea verticillata at any time during the medical history (Table 2), there is insufficient evidence for a diagnosis of FD, despite the presence of a GLA variant.

Angiokeratoma

In an individual with a variant in the GLA gene and clustered angiokeratoma in the bathing trunk area, umbilicus and/or perioral region, there are no known alternative diagnoses but FD.

In an individual with scattered (i.e. not clustered) angiokeratoma, there is insufficient evidence for a diagnosis of FD, despite the presence of a GLA variant. The differential diagnosis of angiokeratoma should be considered (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis of angiokeratoma

| Angiokeratoma | Preferred localisation |

|---|---|

| Angiokeratoma of Fordyce | Scrotal/vaginal |

| Angiokeratoma of Mibelli | Fingers and toes |

| Angiokeratoma corporis circumscriptum | Trunk/extremities |

| Angiokeratoma circumscriptum naeviforme (rare, easily confused with melanoma) | Neck |

| Idiopathic | All localisations |

| Other lysosomal storage disordersa | Related to the corresponding disease |

aOther lysosomal storage disorders that present with angiokeratoma, such as fucosidosis, Schindler’s disease and sialidosis, are rare and have a distinct clinical pattern, dissimilar to FD. In the clinical context, another LSD disease will not likely be mistaken for FD, but additional testing for lysosomal storage disorders can be considered

A skin biopsy of an angiokeratoma may be considered. A biopsy with characteristic storage on EM confirms the diagnosis of FD. However, the pretest likelihood of finding storage in an angiokeratoma or general skin biopsy is unknown for individuals with a nonclassical phenotype of FD, but is considered to be very low (see also Sect. 3.2). For review on the differential diagnosis of angiokeratoma, see Zampetti et al. (2011).

Neuropathic Pain

The differential diagnosis of neuropathic pain and SFN in particular is broad. The neuropathic pain that is caused by FD has a characteristic presentation and is related to the presence of SFN. In 95% of male and 75% of female FD patients, an abnormal heat detection threshold for cold and/or diminished intraepidermal nerve fibre density is found (Biegstraaten et al. 2011, 2012; Uceyler et al. 2011). In case of a variant in the GLA gene and the presence of neuropathic pain in hands and feet starting at childhood and increasing with heat/fever (Biegstraaten et al. 2012; Uceyler et al. 2013), there is no known alternative diagnosis. However, in all patients with pain as the only symptom, neurophysiological tests, quantitative sensory testing and a skin biopsy for intraepidermal nerve fibre density are needed to confirm the presence of isolated SFN, preferably before testing for FD is performed to rule out other causes.

In individuals with a GVUS in the GLA gene and neuropathic pain related to SFN that does not fit the characteristic Fabry neuropathic pain description, there is insufficient evidence for a diagnosis of FD, despite the presence of a GLA variant. The differential diagnosis for SFN should be considered involving an expert on SFN; see Table 4.

Table 4.

Differential diagnosis to be considered in cases of SFN and an uncertain diagnosis of FD

| Isolated SFN | |

|---|---|

| Idiopathic (approximately 40%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus/impaired glucose metabolism | Sarcoidosis |

| Toxin: medication/alcohol/drug induced | HIV |

| Hypothyroidism | Coeliac disease |

| Sjögren’s disease | Postinfection |

| Monoclonal gammopathy | Hyperlipidaemia |

| Amyloidosis | Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy |

| Vasculitis | “Burning feet” syndrome |

| Erythromelalgia | |

Pathology

In addition to the 2-step approach, the feasibility to perform biopsies in individuals with neuropathic pain, AK and/or CV was discussed. In previous consensus procedures it was agreed that characteristic storage on electron microscopy (EM) of an affected organ (i.e. heart or kidney) should be considered as the gold standard for FD (Fogo et al. 2010; Leone et al. 2012; Smid 2014; Van der Tol 2014a, b). The panel is convinced that in the group of patients discussed here (i.e. patients with non-specific neuropathic pain, AK or CV but without heart or kidney involvement), a skin biopsy with characteristic storage on electron microscopy (EM) could confirm the diagnosis of FD.

The presence of characteristic storage in the skin has been well documented in most classical male FD patients (Eng et al. 2001; Thurberg et al. 2004), while reports on skin biopsies in nonclassical FD patients, i.e. who have confirmed storage in a kidney or heart biopsy but not fulfilling the criteria for a definite classical diagnosis of FD (Table 1), are lacking. Thus, it is unknown if a nonclassical phenotype of FD will also coincide with characteristic storage in the skin. Since the prevalence of characteristic skin storage is unknown in these individuals, we do not recommend to perform a skin biopsy in all patients with non-specific neuropathic pain, AK and/or CV and an uncertain diagnosis of FD.

Discussion

In case of an FD-specific pattern of cornea verticillata, angiokeratoma and/or neuropathic pain, and in the absence of other causes for these features, there is no alternative diagnosis than FD. Because of the major implications of an FD diagnosis, it is of great importance to ensure that the feature closely meets the criteria of an FD-specific feature (see Table 1). Yet in case of a GLA GVUS (an uncertain diagnosis of FD) and with cornea verticillata, angiokeratoma and/or neuropathic pain that are non-specific, there are currently no diagnostic tools to confirm or reject the diagnosis of FD. Thus, in these cases there is insufficient evidence for a diagnosis of FD. The expert panel advises to explain to the individual and family members that based upon current knowledge, FD is an unlikely diagnosis. Alternative diagnoses should be considered carefully. This line of argumentation is depicted in the algorithm in Fig. 1.

If no alternative diagnosis is made, it remains uncertain, but still very unlikely, that FD disease plays a role in the development of the clinical feature that was the reason to test for FD. Follow-up in an expert centre for FD could be considered on an individual basis. In case heart, kidney or brain disease develops, the diagnosis should be re-evaluated by applying the respective diagnostic algorithm, e.g. with a kidney biopsy in case of chronic kidney disease (Smid 2014; Van der Tol 2014a, b).

The expert group stressed the need for adequate counselling for these individuals and their family members to avoid unnecessary burden of a chronic illness.

In patients with heart or kidney involvement and an uncertain diagnosis of FD, histological evidence of characteristic storage by electron microscopy in an affected organ is the current gold standard for FD. In the patients who are the subjects of the current study, the heart and kidney are, by definition, not involved. Skin biopsies will, most likely, also yield negative results in the majority of cases. In classical male FD patients, characteristic storage in kidney cells is already present at a young age and in the absence of proteinuria (Tondel et al. 2008). Therefore, it may be postulated to perform a kidney biopsy even in the absence of any clinical signs of kidney disease. However, in case of nonclassical FD without chronic kidney disease, the prevalence of characteristic storage in the kidney (or heart) is currently unknown and expected to be low. Furthermore, Houge et al. reported on a male patient with characteristic storage in the kidney, while kidney biopsies of family members with the GLA variant did not show deposits, illustrating intra-familial differences (Houge et al. 2011). Because of the low expected yield and the inability to exclude future FD-associated organ involvement when storage is absent, a kidney biopsy is currently not recommended.

In individuals with a persisting uncertain diagnosis of FD, based upon clinical judgment, regular follow-up can be considered on an individual basis. If indeed kidney, heart or brain disease develops, a confirmation of the diagnosis should first be made following the subsequent organ-specific diagnostic algorithm, frequently involving a biopsy.

This recommendation does not serve to encourage screening for FD of groups or individuals (van der Tol et al. 2014). However, individuals with a GLA GVUS and thus an uncertain diagnosis of FD are frequently identified. With the recommendations in this study, unnecessary burden, inadequate counselling and unnecessary treatment with costly ERT can be avoided for these individuals and family members. Further studies may indicate new diagnostic tools, and the algorithm may subsequently be updated.

Acknowledgements

This study was performed within the framework of the Dutch Top Institute Pharma (TI Pharma, project number T6-504, “Fabry or not Fabry: valorization of clinical and laboratory tools for improved diagnosis of Fabry disease”). TI Pharma is a non-profit organisation that catalyses research by founding partnerships between academia and industry. Partners: Genzyme, a Sanofi company; Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam; subsidising party: Shire HGT. http://www.tipharma.com/pharmaceutical-research-projects/drug-discovery-development-and-utilisation/hamlet-study.html. The industry partners had no role in the content of this manuscript or selection of panel members. The authors confirm independence from the sponsors; the sponsors have not influenced the content of the article.

RHL is supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

We would like to thank Dr. Anette Møller from the Danish Pain Research Center, University Hospital of Aarhus, Denmark, for her participation in the expert panel.

Synopsis

In patients with an α-galactosidase A gene variant and neuropathic pain, cornea verticillata or angiokeratoma, who have an uncertain diagnosis of Fabry disease, detailed characterisation of these features is essential before the diagnosis of Fabry disease can be confirmed.

Guarantor Marieke Biegstraaten

Ethics approval was not required for this study.

Key words: Fabry disease; Diagnosis; Genetic variant; Consensus

Contributions

L van der Tol, CE Hollak and M Biegstraaten were involved in the design of the study, development of the consensus document, the survey rounds and analyses.

D Cassiman, G Houge, M Janssen, RH Lachmann, GE Linthorst, U Ramaswami, C Sommer, C Tøndel, ML West, F Weidemann, FA Wijburg and E Svarstad and AT Møller took part in the survey rounds as expert panellists.

All authors took part in writing and revising the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Linda van der Tol has received travel support and reimbursement of expenses from Actelion, Shire HGT or Genzyme.

Marieke Biegstraaten, Gabor E Linthorst and Carla EM Hollak have received travel support, honoraria for consultancies and speaker fee from Actelion, Genzyme, Shire HGT, Protalix or Amicus. All fees are donated to the Gaucher Stichting or the AMC Medical Research for research support.

Gunnar Houge has received travel support from Genzyme and Shire.

Robin Lachmann has received honoraria and consultancy fees from Genzyme, Shire and Actelion.

Einar Svarstad has received speaker fee and travel support from Genzyme and Shire.

Camilla Tøndel has received travel support and speakers fee from Shire and Genzyme.

Michael L West received research funds, honoraria and consultant fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Amicus Therapeutics, Genzyme a Sanofi company, GlaxoSmithKline, Shire Human Genetic Therapies and Sumitomo Pharma.

Frank Weidemann received reimbursement of expenses and honoraria for lectures on the management of lysosomal storage diseases from Genzyme a Sanofi company and Shire HGT.

Frits Wijburg has received honoraria, travel grants or research grants from Shire Human Genetic Therapies, Inc., Genzyme and Actelion Pharmaceuticals.

David Cassiman received travel support, speaker fees and research funding from Genzyme-Sanofi, Shire and Actelion, via the University of Leuven and Leuven University Hospitals financial services.

Claudia Sommer has received honoraria and consultancy fees from Baxter, CSL Behring, Genzyme and Pfizer.

Uma Ramaswami and Mirian Janssen have no disclosures to report.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

Contributor Information

Marieke Biegstraaten, Email: M.Biegstraaten@amc.uva.nl.

Collaborators: Johannes Zschocke and K Michael Gibson

References

- Aerts JM, Groener JE, Kuiper S, et al. Elevated globotriaosylsphingosine is a hallmark of Fabry disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(8):2812–2817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712309105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekri S, Enica A, Ghafari T, et al. Fabry disease in patients with end-stage renal failure: the potential benefits of screening. Nephron Clin Pract. 2005;101(1):c33–c38. doi: 10.1159/000085709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegstraaten M, Binder A, Maag R, Hollak CE, Baron R, van Schaik IN. The relation between small nerve fibre function, age, disease severity and pain in Fabry disease. Eur J Pain. 2011;15(8):822–829. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegstraaten M, Hollak CE, Bakkers M, Faber CG, Aerts JM, van Schaik IN. Small fiber neuropathy in Fabry disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;106(2):135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns R, Sheorajpanday R, Braxel E, et al. Middelheim Fabry Study (MiFaS): a retrospective Belgian study on the prevalence of Fabry disease in young patients with cryptogenic stroke. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109(6):479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desnick RJ, Ioannou YA, Eng CM. α-Galactosidase A deficiency: Fabry disease. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. pp. 3733–3774. [Google Scholar]

- Dubuc V, Moore DF, Gioia LC, Saposnik G, Selchen D, Lanthier S. Prevalence of Fabry Disease in young patients with cryptogenic ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;22:1288–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elleder M, Bradova V, Smid F, et al. Cardiocyte storage and hypertrophy as a sole manifestation of Fabry’s disease. Report on a case simulating hypertrophic non-obstructive cardiomyopathy. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1990;417(5):449–455. doi: 10.1007/BF01606034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng CM, Banikazemi M, Gordon RE, et al. A phase 1/2 clinical trial of enzyme replacement in fabry disease: pharmacokinetic, substrate clearance, and safety studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68(3):711–722. doi: 10.1086/318809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogo AB, Bostad L, Svarstad E, et al. Scoring system for renal pathology in fabry disease: report of the international study group of Fabry nephropathy (ISGFN) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2168–2177. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garman SC. Structure-function relationships in alpha-galactosidase A. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2007;1802(2):247–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold H, Mirzaian M, Dekker N, et al. Quantification of globotriaosylsphingosine in plasma and urine of Fabry patients by stable isotope ultraperformance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2013;59(3):547–556. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.192138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Human Genome Database (HGMD) (2014) www.HGMD.org

- Hollander DA, Aldave AJ. Drug-induced corneal complications. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15(6):541–548. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000143688.45232.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houge G, Tondel C, Kaarboe O, Hirth A, Bostad L, Svarstad E. Fabry or not Fabry–a question of ascertainment. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(11):1111. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Ohashi T, Fukuda T, et al. No accumulation of globotriaosylceramide in the heart of a patient with the E66Q mutation in the alpha-galactosidase A gene. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;107(4):711–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone O, Veinot JP, Angelini A, et al. 2011 consensus statement on endomyocardial biopsy from the association for European cardiovascular pathology and the society for cardiovascular pathology. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2012;21(4):245–274. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HY, Chong KW, Hsu JH, et al. High incidence of the cardiac variant of Fabry disease revealed by newborn screening in the Taiwan Chinese population. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2(5):450–456. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.862920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas J, Giese AK, Markoff A, et al. Functional characterisation of alpha-galactosidase a mutations as a basis for a new classification system in fabry disease. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(8):e1003632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechtler TP, Stary S, Metz TF, et al. Neonatal screening for lysosomal storage disorders: feasibility and incidence from a nationwide study in Austria. Lancet. 2012;379(9813):335–341. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61266-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, Carey WF. Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. JAMA. 1999;281(3):249–254. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao S, Takenaka T, Maeda M, et al. An atypical variant of Fabry’s disease in men with left ventricular hypertrophy. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(5):288–293. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508033330504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorthuis BJ, Wevers RA, Kleijer WJ, et al. The frequency of lysosomal storage diseases in The Netherlands. Hum Genet. 1999;105(1–2):151–156. doi: 10.1007/s004399900075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombach SM, Dekker N, Bouwman MG, et al. Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine: diagnostic value and relation to clinical manifestations of Fabry disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802(9):741–748. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smid BE, Van der Tol L, Cecchi F et al (2014) Consensus recommendation on Fabry disease diagnosis in adult patients with left ventricular hypertrophy. Manuscript submitted [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spada M, Pagliardini S, Yasuda M, et al. High incidence of later-onset fabry disease revealed by newborn screening. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79(1):31–40. doi: 10.1086/504601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terryn W, Vanholder R, Hemelsoet D, et al. Questioning the pathogenic role of the GLA p.Ala143Thr “mutation” in Fabry disease: implications for screening studies and ERT. JIMD Rep. 2013;8:101–108. doi: 10.1007/8904_2012_167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurberg BL, Randolph BH, Granter SR, Phelps RG, Gordon RE, O’Callaghan M. Monitoring the 3-year efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy in fabry disease by repeated skin biopsies. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(4):900–908. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tondel C, Bostad L, Hirth A, Svarstad E. Renal biopsy findings in children and adolescents with Fabry disease and minimal albuminuria. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(5):767–776. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uceyler N, He L, Schonfeld D, et al. Small fibers in Fabry disease: baseline and follow-up data under enzyme replacement therapy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2011;16(4):304–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2011.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uceyler N, Ganendiran S, Kramer D, Sommer C (2013) Characterization of pain in Fabry disease. Clin J Pain [DOI] [PubMed]

- van der Tol L, Svarstad E, Ortiz A et al (2014a) Chronic kidney disease and an uncertain diagnosis of Fabry disease: approach to a correct diagnosis. Manuscript submitted [DOI] [PubMed]

- van der Tol L et al (2014b) Diagnosis of Fabry disease in adults with stroke and/or WMLs without characteristic signs or symptoms of Fabry disease and a genetic variant of unknown significance: a systematic review and consensus recommendation. Manuscript in preparation

- van der Tol L, Smid BE, Poorthuis BJ, et al. A systematic review on screening for Fabry disease: prevalence of individuals with genetic variants of unknown significance. J Med Genet. 2014;51(1):1–9. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin EF, Clatworthy MR, Pritchard NR. Fabry disease: results of the first UK hemodialysis screening study. Clin Nephrol. 2011;75(6):506–510. doi: 10.5414/CNP75506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampetti A, Orteu CH, Antuzzi D, et al. Angiokeratoma: decision making methodology for the diagnosis of Fabry disease. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:712–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]