Abstract

Non-invasive detection of caspase-3/7 activity in vivo has provided invaluable predictive information regarding tumor therapeutic efficacy and anti-tumor drug selection. Although a number of caspase-3/7 targeted fluorescence and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging probes have been developed, there is still a lack of gadolinium (Gd)-based magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) probes that enable high spatial resolution detection of caspase-3/7 activity in vivo. Here we employ a self-assembly approach and develop a caspase-3/7 activatable Gd-based MRI probe for monitoring tumor apoptosis in mice. Upon reduction and caspase-3/7 activation, the caspase-sensitive nano-aggregation MR probe (C-SNAM: 1) undergoes biocompatible intramolecular cyclization and subsequent self-assembly into Gd-nanoparticles (GdNPs). This results in enhanced r1 relaxivity—19.0 (post-activation) vs. 10.2 mM−1 s−1 (pre-activation) at 1 T in solution—and prolonged accumulation in chemotherapy-induced apoptotic cells and tumors that express active caspase-3/7. We demonstrate that C-SNAM reports caspase-3/7 activity by generating a significantly brighter T1-weighted MR signal compared to non-treated tumors following intravenous administration of C-SNAM, providing great potential for high-resolution imaging of tumor apoptosis in vivo.

Introduction

Activatable Gd-based contrast agents that modulate their properties (relaxivity) in response to molecular targets can greatly improve detection sensitivity and specificity of molecular MRI in living systems.1–4 The activation of Gd-based MRI contrast agents produces contrast enhancement by modulating the r1 relaxivity through either changes in the number of coordinated water molecules (q), the inner sphere water exchange time (τm), the molecular tumbling time (τR), or the number of paramagnetic ion centers, upon interaction with the molecular targets (e.g. pH, redox potential, metal ions, or enzymes).5–11 A number of enzyme-activatable MRI probes have been developed by taking advantage of the catalytic activity as a convenient mechanism for the efficient modulation of relaxivity from either enzyme-triggered chemical conversion12–15 or receptor binding (i.e., RIME, receptor-induced magnetization enhancement)16–19. One of the well-known examples12 is a conjugate of β-galactose and the Gd chelate—EgadME for MR imaging of β-Gal gene expression in the live zebra fish embryo by hydrolysis of the sugar with β-galactosidase, resulting in an increase of q. Another example13,20 was demonstrated by conjugation of 5-hydrotryptamide and Gd chelate for MR imaging of myeloperoxidase activity in inflammation tissue through the formation of oligo/polymeric structures, resulting in prolonged τR.

Self-assembly of small molecules into supramolecular complexes has been widely applied for developing new functional nanomaterials for myriads of applications in biology and medicine.21–24 Controlled self-assembly of small synthetic Gd complexes into nano/micro structures (e.g., GdNPs) would amplify the r1 relaxivity as a result of increased τR, providing a smart approach to designing activatable MRI probes. We have previously described an activatable Gd-based MRI probe based on controlled self-assembly strategy to generate enhanced r1 relaxivity.25,26 The activation proceeds through the disulfide reduction to yield free 1,2-aminothiol in the cysteine, followed by a condensation reaction with 2-cyanobenzothiozle (CBT) in the molecule to produce polymers, subsequently self-assembled into GdNPs. Recently, Liang and co-workers introduced a peptide substrate into the probe so the activation was enabled by the activity of a protease furin.27 One potential complexity of this system is the competition from the reaction between CBT in the probe and the endogenous free cysteine—that prevents polymerization and self-assembly. Multi-injection of high dosage of the probe was required when applied in a human tumor xenograft mouse model. To effectively outcompete free cysteine, we have optimized our controlled self-assembly strategy by turning the intermolecular polymerization system to an intramolecular macrocyclization chemistry.27 This new system has been successfully demonstrated by imaging enzyme activity both in cells and living mice with fluorescence28,29 and PET probes30. In this study, we show that this optimized self-assembly strategy can be applied to develop a caspase-3/7-activatable Gd-based MRI probe.

Caspases are a family of cysteine proteases that play essential roles in apoptosis by initiating, regulating, and executing downstream proteolytic events during programmed cell death. It has been recognized that radio- and chemotherapy-induced tumor cell death often leads to the activation of caspase-3/7, an “executioner” for cell apoptosis.31,32 Therefore, caspase-3/7 has become an important early biomarker for evaluating apoptosis-promoting antitumor therapies, imaging of which can provide invaluable predictive information regarding therapeutic efficacy and anti-cancer drug selection.33 A number of activatable fluorescent probes34–37 and radiolabeled PET tracers30,38–40 have been developed for imaging of caspase-3/7 activity in apoptotic cells and living mice. Recently, an activatable thullium-based paramagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer (PARACEST) MRI probe41 and paramagnetic relaxation-based 19F MRI probes42,43 have also been reported, however, their ability to image caspase-3 activity in cells and in vivo is compromised by the relatively lower detection sensitivity of PARACEST and 19F MRI agents. Here we report a caspase-3/7-activatable MRI probe that employs chelated Gd, one of the most common clinically used MRI contrast agents to enhance contrast, to non-invasive MR imaging of caspase-3/7 activity in drug-induced apoptotic tumors in living mice.

Results and discussion

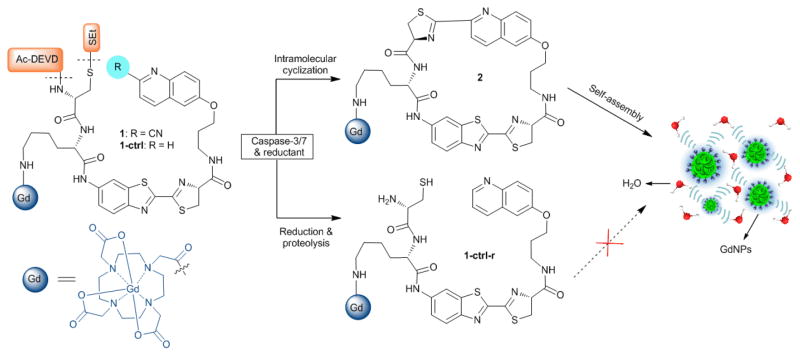

Design of caspase-3/7 activatable and control MRI probes

Fig. 1 presents the design of the caspase-sensitive nano-aggregation MRI probe (C-SNAM, or 1) which consists of: a 2-cyano-6-hydroxyquinoline (CHQ) and a D-cysteine residue for efficient biocompatible cyclization, a DEVD peptide recognized by active caspase-3/7, a disulfide bond reduced by intracellular glutathione (GSH), and a Gd-DOTA monoamide chelate as the MRI reporter. The reducing intracellular environment in mammalian cells (i.e. up to 10 mM GSH) would provide a simple, convenient approach to control the intracellular reduction of the disulfide bond in 1. Disulfide reduction and caspase-3/7 activation that initiates DEVD peptide cleavage will trigger intramolecular cyclization of 1. Unlike the flexible precursor 1, the macrocyclic product 2 is more rigid and hydrophobic, and can further self-assemble into GdNPs, as a result of the increased intermolecular interactions (i.e. hydrophobic interaction, π-π stacking). GdNPs have an increased r1 relaxivity relative to the unactivated probe, presumably due to an increased τR. The control probe 1-ctrl has a quinolin-6-yl ring replacing the CHQ moiety in 1, preventing intramolecular cyclization following DEVD peptide cleavage by caspase-3 and abrogating GdNPs formation. Therefore, 1-ctrl is able to discern the relative contributions of peptide cleavage and triggered self-assembly to the mechanism of MR contrast enhancement. Both probes were synthesized and characterized as outlined in Supporting Information (ESI: Scheme S1–3).

Fig. 1.

The chemical structures of probe C-SNAM (1) and its control probe 1-ctrl, and the proposed chemical conversions following disulfide reduction and caspase-3/7-triggered DEVD peptide cleavage.

Controlled macrocyclization and self-assembly of 1 into GdNPs in vitro

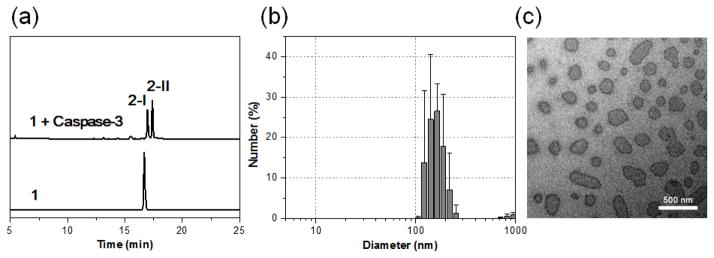

Macrocyclization of 1 to 2 was monitored in solution using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and high-resolution mass spectroscopic (HRMS) analysis. After 5 h incubation with recombinant human caspase-3 (50 nM) in enzyme reaction buffer, 1 (200 μM) (TR = 16.7 min) was efficiently converted to two cyclized products 2-I (TR = 17.0 min) and 2-I (TR = 17.4 min), which are probable diastereoisomers arising from two different ring-closing orientations28,29 (Fig. 2a). In contrast, after 24 h of incubation of 1-ctrl with caspase-3, only the DEVD peptide cleaved and disulfide reduced products 1-ctrl-r were observed (ESI: Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Caspase-3 mediated macrocyclization and self-assembly into GdNPs in vitro. (a) HPLC traces of 1 (bottom) and the incubation of 1 (200 μM) with recombinant human caspase-3 (50 nM) in the caspase buffer at 37 °C for 5 h (top). (b) DLS analysis of 1 (200 uM) following incubation with caspase-3 (50 nM) in caspase buffer (pH 7.4) overnight. Error bars indicated standard deviation, coming from three repeated measurements. (c) TEM images of GdNPs formed in the solution shown in (b). Scale bar: 500 nm.

The formation of GdNPs in solution after caspase-3 activation was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS), showing the aggregation of particles with a mean hydrodynamic radius of ~164 nm (Fig. 2b). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed the shapes of separated GdNPs with diameters ranging from 50 to a few hundred nanometers (Fig. 2c). The presence of Gd in the particles was further verified by energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy (ESI: Fig. S2).

Characterization of MR properties in vitro

Water proton r1 relaxivities of 1 and 1-ctrl before and after caspase-3 incubation were then measured at 1, 1.5 and 3 T (ESI: Fig. S3). The relaxivity of isolated cyclized products 2-I and 2-II, was also measured for comparison. As shown in Table 1, the relaxivities of 1 and 1-ctrl were similar and higher than Dotarem at all three magnetic fields. The larger relaxivities are in line with a larger molecular size of 1 and 1-ctrl compared to Dotarem, resulting in longer τR. As expected, caspase-3 incubation enhanced the relaxivity of probe 1, probably due to a further increase in τR after the formation of GdNPs in solution26,44. The r1 value of 1 upon caspase-3 activation was ~ 19.0 mM−1 s−1 at 1 T, which is ~86% higher than that of 1 before activation (10.2 mM−1 s−1), and ~322% higher than Dotarem (4.5 mM−1 s−1). In contrast, incubation of 1-ctrl with caspase-3 gave slightly reduced relaxivities (−7% at 1 T), which is expected given the decreased size of the cleaved, but non-cyclized, products. These results validate the rationale in our probe design: namely, that caspase-3 activated self-assembly of cyclized products from 1 into GdNPs generates higher per Gd relaxivity at low magnetic field strengths45, and that this self-assembly does not occur for cleaved products of 1-ctrl. The higher relaxivity of 1 after caspase-3 activation was further demonstrated by T1-weighted MR imaging at 1.5 T (Fig. 3c). Moreover, it should be noted that the isolated cyclized products 2-I and 2-II gave similar relaxivities compared to 1 upon caspase-3 incubation, indicating a high efficacy for capase-3 activation.

Table 1.

Relaxivities of Gd-based MR probes at different magnetic field strengths

| MR Probe | Effective r1 Relaxivity (mM−1 s−1) a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 T | 1.5 T | 3 T | |

| 1 | 10.2 ± 1.5 | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 9.3 ± 0.6 |

| 1-ctrl | 10.1 ± 0.1 | 10.0 ± 0.2 | 9.1 ± 0.2 |

| 1 + Caspase-3 b | 19.0 ± 0.5 | 15.6 ± 0.4 | 10.3 ± 0.5 |

| 1-ctrl + Caspase-3 b | 9.4 ± 0.1 | 8.8 ± 0.6 | 8.2 ± 0.1 |

| 2-I | 18.1 ± 0.2 | 15.0 ± 0.1 | 9.8 ± 0.2 |

| 2-II | 17.0 ± 0.1 | 14.8 ± 0.1 | 10.5 ± 0.3 |

| Dotarem c | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.1 |

The relaxation times T1 were measured in enzyme reaction buffer (pH 7.4) using the standard inversion recovery spin-echo sequence on 1 T scanner at r.t., 1.5 T and 3 T MR scanners at 37 °C. The Gd3+ concentration was calibrated using ICP-MS. These concentration dependent T1 values were plotted versus Gd3+ concentration, and the rising curve was fitted by linear regression to calculate molar relaxivity r1 (see ESI for the detail). The data was shown as mean ± SD.

1 or 1-ctrl (50–500 μM) was incubated with caspase-3 (50 nM) in the caspase buffer at 37 °C overnight.

Measured in PBS buffer (pH 7.4).

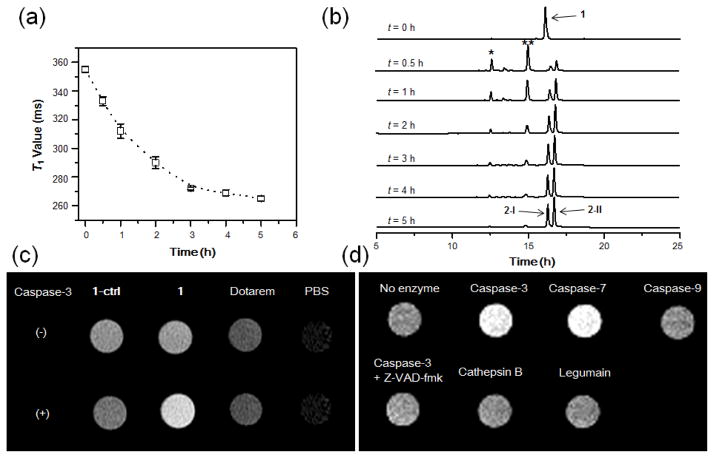

Fig. 3.

MR studies with 1 in vitro. (a) Time-dependent T1 value reduction of 1 (200 μM) in the presence of caspase-3 (40 nM) in enzyme reaction buffer at 37 °C. T1 value (1 T) at each time point was measured with Bruker Minispec (mq40 NMR analyzer) at 37 °C, using the standard inversion recovery program. Data represent mean values ± standard deviation, n = 2. (b) HPLC traces of 1 (200 μM) upon incubation with caspase-3 (40 nM) from 0 to 5 h. Peaks * and ** indicate disulfide reduced intermediates of 1. (c) T1-weighted images show brighter MR signal for 1 than other probes upon caspase-3 incubation. MR probes 1, 1-ctrl, and Dotarem at 75 μM in enzyme reaction buffer were incubated with and without caspase-3 (20 nM) at 37 °C overnight. T1-weighted spin-echo images (TE/TR = 11/900 ms) of the incubation solutions were acquired at 1.5 T at 37 °C. (d) Brighter T1-weighted images of 1 were produced by caspase-3/7 than other enzymes. Probe 1 (208 μM) was incubated with indicated protease (50 nM) in enzyme reaction buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C overnight. T1-weighted spin-echo images (TE/TR = 15/150 ms) of the incubation solutions were acquired at 1 T at r.t.

Next, the activation kinetics of 1 by caspase-3 was evaluated by monitoring the T1 value change of probe 1 solution (200 μM) upon addition of caspase-3 (50 nM) over time in enzyme reaction buffer (Fig. 3a). A gradual and quick reduction of T1 value in solution was observed after incubation with caspase-3 from 0 to 5 h. This was further confirmed by HPLC measurement, showing a fast kinetics for caspase-3 catalyzed hydrolysis and macrocyclization of 1 (Fig. 3b). Enzyme specificity was examined using both the T1-weighted imaging and T1 value (1 T) measurement of 1 incubated with nine relevant subcellular proteases (caspase-1, 3, -7, -9, cathepsin B, D, L, S and legumain) in buffer. Significantly brighter T1-weighted images were observed for both of the effector caspases (-3 and -7) that are activated during cell apoptosis and are capable of cleaving the same DEVD peptide sequence34 (Fig. 3d, ESI: Fig. S5). These brighter signals were consistent with the similarly reduced T1 value of 1 following incubation with caspase-3 and -7 relative to either initiator caspase-9 or off-target lysosomal proteases (cathepsin B, D, L, S and legumain) (ESI: Fig. S4,5b). The reduced T1 value in solution was inhibited by the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk (50 μM), confirming good selectivity of 1 for caspase-3/7 detection. Furthermore, by virtue of bioorthogonal enzymatic activation, where one molecule of caspase-3 activates many molecules of probe, probe 1 (208 μM) also shows good sensitivity to detect caspase-3 activity in solution (as low as 5 nM) according to the T1 measurements (ESI: Fig. S6).

MR imaging of caspase-3/7 activity in drug-treated cancer cells

The cytotoxicity was firstly evaluated by incubation of viable HeLa cells with 1 at 250 μM for 24 h, and no adverse effects on cell viability were observed (ESI: Fig. S7). The apoptotic cell model was validated by treating HeLa cells with a broad-spectrum protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine (STS, 2 μM) as reported previously.29,46 Caspase-3/7 assays confirmed that the lysates of STS-treated cells showed ~10.5-fold higher caspase-3/7 activity than that of non-treated viable cells (ESI: Fig. S8). The enhanced caspase-3/7 activity was further confirmed by the incubation of STS-treated and non-treated HeLa cells with a caspase-3/7-sensitive fluorescent probe (1-FITC), which showed an intense green fluorescence only in apoptotic cells (ESI: Fig. S9).

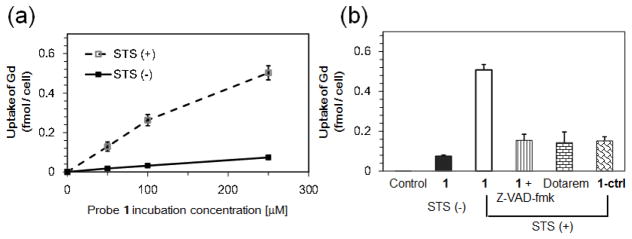

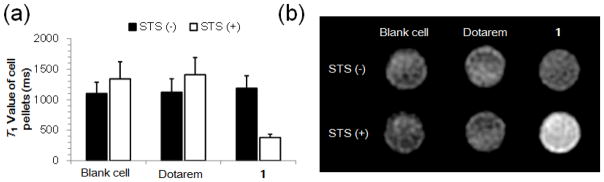

Next, the cellular uptake of Gd was measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis of the amount of Gd in viable and apoptotic cells after incubation with 1 (50, 100, 250 μM) for 24 h. This showed a concentration-dependent uptake in both viable and apoptotic cells (Fig. 4a). The cellular uptake of Gd in STS-treated cells was ~0.5 fmol/cell with 250 μM of 1, which was ~6.6-fold of that in non-treated cells. This uptake enhancement can be inhibited by the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk (50 μM), confirming the caspase-dependent accumulation of 1 in apoptotic cells. As controls, the incubation of STS-treated cells with either 1-ctrl or Dotarem gave much lower uptakes of Gd (Fig. 4B). An MRI study of the cell pellets at 1 T showed a significantly (~3-fold) reduced T1 value in STS-treated cells after incubation with 1 (250 μM) as compared to non-treated cells (Fig. 5A). There was no significant reduction in T1 value between STS-treated and non-treated cells incubated with Dotarem. The much shorter T1 value was consistent with the results of T1-weighted images of cell pellets as shown in Fig. 5b, where STS-treated cells appeared brighter than non-treated cells after incubation with 1. These results suggest that higher caspase-3/7 activity in apoptotic cells can trap 1 inside cells, resulting in higher MRI contrast to allow better differentiation of apoptotic and viable cancer cells.

Fig. 4.

Cell uptake studies with 1. (a) ICP-MS analysis of Gd uptake in viable and STS-induced apoptotic HeLa cells with 1. HeLa cells were untreated or treated with 2 μM STS for 4 h, and then incubated with 0, 50, 100, and 250 μM of 1 for 24 h. After incubation, the cell pellets were collected, washed with PBS, and digested with 69% HNO3. The uptake of Gd in cells was obtained from ICP-MS analysis, and normalized to cell number. Each data point and error bar represents the mean and standard deviation of three experiment results. (b) ICP-MS analysis of Gd uptake in apoptotic HeLa cells with different Gd-based MRI probes at 250 μM for 24 h. Each data point and error bar represents the mean and standard deviation of three experimental results.

Fig. 5.

MR studies of cell incubating with 1. (a) T1 values (1 T) of viable and apoptotic HeLa cell pellets after incubation with 250 μM of 1 or Dotarem for 24 h. (b) T1-weighted MR images (3T, TE/TR = 30/100 ms) of viable and apoptotic HeLa cell pellets after incubation with 250 μM 1 or Dotarem for 24 h.

MR imaging of drug-induced tumor death in mice

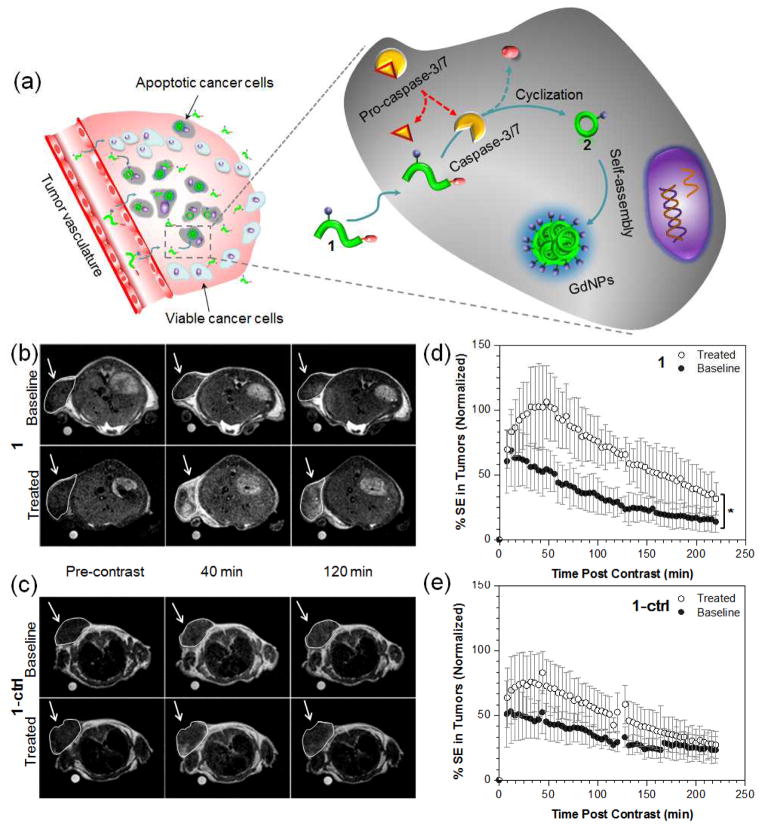

The mechanism of action of C-SNAM (1) for imaging of caspase-3/7 activity in chemotherapy-induced apoptotic tumor cells in vivo is illustrated in Fig. 6a. After intravenous administration, probe 1 can rapidly extravasate and penetrate into tumor tissue due to its relatively small size. In viable tumor cells, pro-caspase-3/7 dominates, which cannot cleave DEVD caging peptide from 1, leading to rapid diffusion of 1 away from the tumor. In apoptotic tumor cells, the increase in cell membrane permeability upon progression through apoptosis to cell death is well characterized47–49, enhancing the ability of 1 to partition into apoptotic tumor cells; pro-caspase-3 is efficiently converted to active caspase-3 which in turn cleaves the DEVD capping group, and the reductive intracellular microenvironment reduces the disulfide, the combination of which initiates the intramolecular cyclization and aggregation to form GdNPs. In addition to enhanced r1 relaxivity, the GdNPs also show prolonged retention in chemotherapy-responsive tumors due to their large size. Both features enhance the resultant MRI contrast for in vivo applications.

Fig. 6.

Non-invasive MR imaging of tumor cell death in mice. (a) The proposed mechanism of 1 for in vivo MR imaging of caspase-3/7 activity in a chemotherapy-responsive tumor. (b, c) Representative T1-weighted MR images (1T) of HeLa tumors prior to (baseline) or following treatment with DOX (treated). Images were obtained before (pre-contrast), 40 and 120 min after i.v. injection of 0.1 mmol/kg of 1 (b) or 1-ctrl (c). (d, e) The average longitudinal % signal enhancement (% SE) in baseline (●) and treated (○) tumors after i.v. injection of 1 (n = 8, c) or 1-ctrl (n = 4, d) at 0.1 mmol/kg dose. The tumor signal intensity(SI) was normalized to the reference standard in a mini-NMR tube (1 mM of Dotarem in PBS), and % SE was calculated at each time point as the % difference between the tumor SI at that time point and the tumor SI in the pre-contrast (t = 0) dataset. * p < 0.05. Error bars are standard deviation.

Evaluation of 1 for MR imaging of caspase-3/7 activity in vivo was performed on nude mice bearing subcutaneous HeLa tumors. Tumors were implanted and grown for 10–15 days before receiving two intratumoral injections of doxorubicin (0.2 mg each) separated by 2 days. MR imaging was carried out the day before treatment (baseline) and four days post treatment (treated) following intravenous injection (i.v.) of 1 or 1-ctrl (0.1 mmol/kg). Spin-echo T1-weighted multi-slice MR images at 1 T were acquired prior to (pre-contrast) and every 4 min following contrast agent administration (post-contrast), and scanning was carried out for 4 h post-contrast for each mouse.

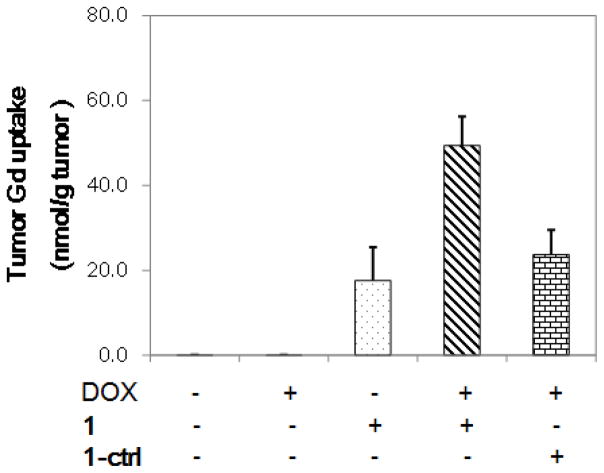

As shown in Fig. 6b, higher MR signals (increased T1 contrast) were observed 40 and 120 min after i.v. injection of 1 in treated tumors as compared to that in baseline tumors or in treated tumors that received 1-ctrl (Fig. 6c). The percentage signal enhancement (% SE) between post-contrast and pre-contrast in treated tumors was significantly higher than that in baseline tumors after administration of 1 (n = 8, p < 0.05, Fig. 6d, ESI: Movie S1). The maximum % SE in treated tumors was ~102% at 40–60 min post-injection, which is in contrast to that of a maximum of ~60% at 0–12 min in baseline tumors, indicating a higher uptake and prolonged accumulation in tumors after DOX-treatment. This was further underscored by comparing the MR signal intensity in tumors: it was ~110% higher in treated tumor than that in baseline tumors at 40 min, and further increased to ~170% at 120 min. In the case of 1-ctrl, there was no statistically significant difference in % SE during the time course of imaging (up to 4 h) between treated and baseline tumors (n = 4, p > 0.05, Fig. 6e, ESI: Movie S2). These findings support our hypothesis that the formation of GdNPs triggered by caspase-3/7 resulted in prolonged retention in tumor tissues relative to unactivated contrast agent. ICP-MS analysis of Gd uptake in tumors confirmed significantly higher Gd levels in treated tumors after injection of 1 (Fig. 7). The enhanced MR signals in treated tumors with 1 correlated well with the caspase-3/7 level detected in tumors (ESI: Fig. S10). In addition, we did not observe obvious signs of toxicity in mice during experiments and up to two weeks after probe injection. The above results indicate the feasibility of probe 1 for rapid and non-invasive monitoring of tumor response to chemotherapy in living mice. Currently, on-going work is focused on further evaluation of the probe in more clinically relevant animal models as well as its long-term toxicity in vivo. These studies will provide valuable insights for the translational potential of C-SNAM.

Fig. 7.

ICP-MS analysis of tumor Gd uptake. Mice bearing subcutaneous HeLa tumors were untreated or treated with DOX (0.2 mg × 2). After treatment, 1 or 1-ctrl (0.1 mmol kg−1) was injected i.v., and the mice were sacrificed after 1 h. The tumors were resected, weighted, and digested with 69% HNO3. The total Gd amount was analyzed by ICP-MS, and the tumor Gd uptake was normalized to tumor weight. Each data point and error bar represents the mean and standard deviation of 5 mice.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have reported a novel caspase-3/7-activatable Gd-based MRI probe C-SNAM for imaging chemotherapy-induced tumor apoptosis in mice. This activatable MRI probe undergoes biocompatible intramolecular cyclization and subsequent self-assembly into GdNPs upon reduction and caspase-3/7 activation, resulting in enhanced r1 relaxivity (86%) and longer retention in apoptotic tumors. The controlled self-assembly strategy of using caspase-3/7 to activate a small molecule contrast agent to achieve significantly enhanced r1 relaxivities and stronger MR signal may serve as a general approach to design activatable MRI probes for molecular imaging of enzyme activity in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the Stanford University National Cancer Institute (NCI) Centers of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence (1U54CA151459-01) and the NCI ICMIC@Stanford (1P50CA114747-06). A.S. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Susan Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. P.P. was a fellow of the Stanford Molecular Imaging Scholars program (NIH R25 CA118681). We thank Drs. Caroline Harris and Karrie Weaver from the ICP-MS/TIMS facility at Stanford University for assistance with ICP-MS experiments.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available:full experimental details of probe synthesis and characterization, relaxivity measurement, cell culture, animal protocol and MR imaging.

Contributor Information

Brian Rutt, Email: brutt@stanford.edu.

Jianghong Rao, Email: jrao@stanford.edu.

Notes and references

- 1.Shen C, New EJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Que EL, Chang CJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;39:51–60. doi: 10.1039/b914348n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Leon-Rodriguez LM, Lubag AJ, Malloy CR, Martinez GV, Gillies RJ, Sherry AD. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:948–957. doi: 10.1021/ar800237f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Major JL, Meade TJ. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:893–903. doi: 10.1021/ar800245h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Que EL, New EJ, Chang CJ. Chem Sci. 2012;3:1829–1834. doi: 10.1039/C2SC20273E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viger ML, Sankaranarayanan J, de Gracia Lux C, Chan M, Almutairi A. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:7847–7850. doi: 10.1021/ja403167p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinelli J, Fekete M, Tei L, Botta M. Comm Commun. 2011;47:3144–3146. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05428c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li WH, Meade TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:1413–1414. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe MP, Parker D, Reany O, Aime S, Botta M, Castellano G, Gianolio E, Pagliarin R. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7601–7609. doi: 10.1021/ja0103647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nivorozhkin AL, Kolodziej AF, Caravan P, Greenfield MT, Lauffer RB, McMurry TJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:2903–2906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies GL, Kramberger I, Davis JJ. Chem Commun. 2013;49:9704–9721. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44268c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louie AY, Huber MM, Ahrens ET, Rothbacher U, Moats R, Jacobs RE, Fraser SE, Meade TJ. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:321–325. doi: 10.1038/73780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogdanov A, Jr, Matuszewski L, Bremer C, Petrovsky A, Weissleder R. Mol Imaging. 2002;1:16–23. doi: 10.1162/15353500200200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duimstra JA, Femia FJ, Meade TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12847–12855. doi: 10.1021/ja042162r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arena F, Singh JB, Gianolio E, Stefania R, Aime S. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:2625–2635. doi: 10.1021/bc200486j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Overoye-Chan K, Koerner S, Looby RJ, Kolodziej AF, Zech SG, Deng Q, Chasse JM, McMurry TJ, Caravan P. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6025–6039. doi: 10.1021/ja800834y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Leon-Rodriguez LM, Lubag A, Udugamasooriya DG, Proneth B, Brekken RA, Sun X, Kodadek T, Dean Sherry A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12829–12831. doi: 10.1021/ja105563a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sim N, Gottschalk S, Pal R, Engelmann Jörn, Parker David, Mishra Anurag. Chem Sci. 2013;4:3148–3153. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anurag Mishra SG, Engelmannb J, Parker D. Chem Sci. 2012;3:131–135. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen JW, Querol Sans M, Bogdanov A, Jr, Weissleder R. Radiology. 2006;240:473–481. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2402050994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao Y, Shi J, Yuan D, Xu B. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1033. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Liang G. Theranostics. 2012;2:139–147. doi: 10.7150/thno.3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Randolph LM, Chien MP, Gianneschi NC. Chem Sci. 2012;3:1363–1380. doi: 10.1039/C2SC00857B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takaoka Y, Sun Y, Tsukiji S, Hamachi I. Chem Sci. 2010;2:511–520. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang G, Ren H, Rao J. Nat Chem. 2010;2:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nchem.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang G, Ronald J, Chen Y, Ye D, Pandit P, Ma ML, Rutt B, Rao J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:6283–6286. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao CY, Shen YY, Wang JD, Li L, Liang GL. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1024. doi: 10.1038/srep01024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye D, Liang G, Ma ML, Rao J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:2275–2279. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye D, Shuhendler AJ, Cui L, Tee SS, Tong L, Tikhomirov G, Felsher D, Rao J. Nat Chem. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1920. advanced online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen B, Jeon J, Palner M, Ye D, Shuhendler A, Chin FT, Rao J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:10511–10514. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kettunen M, Brindle K. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2005;47:175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. Cell. 1997;89:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blankenberg FG. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:81S–95S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi H, Kwok RT, Liu J, Xing B, Tang BZ, Liu B. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:17972–17981. doi: 10.1021/ja3064588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson JR, Kocher B, Barnett EM, Marasa J, Piwnica-Worms D. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012;23:1783–1793. doi: 10.1021/bc300036z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bullok KE, Maxwell D, Kesarwala AH, Gammon S, Prior JL, Snow M, Stanley S, Piwnica-Worms D. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4055–4065. doi: 10.1021/bi061959n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu M, Li L, Wu H, Su Y, Yang PY, Uttamchandani M, Xu QH, Yao SQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12009–12020. doi: 10.1021/ja200808y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen QD, Smith G, Glaser M, Perumal M, Arstad E, Aboagye EO. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16375–16380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901310106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Challapalli A, Kenny LM, Hallett WA, Kozlowski K, Tomasi G, Gudi M, Al-Nahhas A, Coombes RC, Aboagye EO. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1551–1556. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.118760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia CF, Chen G, Gangadharmath U, Gomez LF, Liang Q, Mu F, Mocharla VP, Su H, Szardenings AK, Walsh JC, Zhao T, Kolb HC. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013;15:748–757. doi: 10.1007/s11307-013-0646-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoo B, Pagel MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14032–14033. doi: 10.1021/ja063874f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizukami S, Takikawa R, Sugihara F, Hori Y, Tochio H, Walchli M, Shirakawa M, Kikuchi K. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:794–795. doi: 10.1021/ja077058z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mizukami S, Takikawa R, Sugihara F, Shirakawa M, Kikuchi K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:3641–3643. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kielar F, Tei L, Terreno E, Botta M. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7836–7837. doi: 10.1021/ja101518v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geninatti-Crich S, Szabo I, Alberti D, Longo D, Aime S. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2011;6:421–425. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stepczynska A, Lauber K, Engels IH, Janssen O, Kabelitz D, Wesselborg S, Schulze-Osthoff K. Oncogene. 2001;20:1193–1202. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pozarowski P, Huang X, Halicka DH, Lee B, Johnson G, Darzynkiewicz Z. Cytometry A. 2003;55:50–60. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park D, Don AS, Massamiri T, Karwa A, Warner B, MacDonald J, Hemenway C, Naik A, Kuan KT, Dilda PJ, Wong JWH, Camphausen K, Chinen L, Dyszlewski M, Hogg PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2832–2835. doi: 10.1021/ja110226y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pace NJ, Pimental DR, Weerapana E. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:8365–8368. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.