Abstract

The past decade has witnessed a flurry of empirical and theoretical research on morality and empathy, as well as increased interest and usage in the media and the public arena. At times, in both popular and academia, morality and empathy are used interchangeably, and quite often the latter is considered to play a foundational role for the former. In this article, we argue that, while there is a relationship between morality and empathy, it is not as straightforward as apparent at first glance. Moreover, it is critical to distinguish between the different facets of empathy (emotional sharing, empathic concern, and perspective taking), as each uniquely influences moral cognition and predicts differential outcomes in moral behavior. Empirical evidence and theories from evolutionary biology, developmental, behavioral, and affective and social neuroscience are comprehensively integrated in support of this argument. The wealth of findings illustrates a complex and equivocal relationship between morality and empathy. The key to understanding such relations is to be more precise on the concepts being used, and perhaps abandoning the muddy concept of empathy.

Keywords: morality, empathy, emotional sharing, empathic concern, perspective taking, social and affective neuroscience, developmental science, ventromedial prefrontal cortex

References to morality and empathy appear more and more often in the popular press, political campaigns and in the study of a wide range of topics, including medical care, psychopathy, justice, engagement with art, and so much more. Best-selling popular books, such as the Empathic Civilization (Rifkin, 2009) or the Age of Empathy (de Waal, 2010), make grandiose claims about why morality and empathy are so important and need to be cultivated if we, as a species, want to survive. This year alone, hundreds of publications have used the term “empathy” in both human and animal research. If one looks carefully at the content of these articles, it is far from clear that the same phenomena was actually studied (it can indeed range from yawning contagion in dogs, to distress signaling in chickens, to patient-centered attitudes in human medicine). Thus, with perhaps the exception of some scholars in affective neuroscience and developmental psychology, the concept of empathy has become an umbrella term, and therefore is a source of confusion to too many of our colleagues. As a further first-hand experience, the two authors (JD and JMC) were struck while attending a recent international society meeting, which focused on the development of morality, by so much misunderstanding and confusion over the concept of empathy and its relations to moral cognition. Systematically, every time one attendee would ask a question about, say the role of empathy in a given moral judgment task, the respondent would in turn reply, “what do you mean by empathy?” These ambiguities, combined with our current research on the neurodevelopment of morality, empathy, and prosocial behavior, motivated the writing of this paper.

Overview

Although there is a relationship between morality and empathy, we argue in this paper that these two constructs should not be used interchangeably, and further that the nature of the relationship is not straightforward. Simplifying the relationship between the two is a serious problem given their respective evolutionary, cognitive, and neurobiological mechanisms, and also leads to misconceptions.

Empathy plays an essential role in interpersonal relations including early attachment between primary caregiver and child, caring for the wellbeing of others, and facilitating cooperation among group members. The lack of empathy is a hallmark characteristic of psychopathy and, in these individuals, is associated with callous disregard for the wellbeing of others, guiltlessness, and little appreciation of moral wrongdoing. Moreover, research with healthy participants and patients with neurological damage indicates that utilitarian judgments are facilitated by a lack of empathic concern.

In reality, empathy is not always a direct avenue to moral behavior. Indeed, at times empathy can interfere with moral decision-making by introducing partiality, for instance by favoring kin and in-group members. But empathy also provides the emotional fire and a push toward seeing a victims’ suffering end, irrespective of its group membership and social hierarchies. Empathy can prevent rationalization of moral violations. Studies in social psychology have indeed clearly shown that morality and empathy are two independent motives, each with its own unique goal. In resource-allocation situations in which these two motives conflict, empathy can become a source of immoral behavior (Batson et al., 1995).

In this article, we illuminate the complex relation between morality and empathy by drawing on theories and empirical research in evolutionary biology, developmental psychology, and social neuroscience. We first specify what the concepts of morality and empathy encompass. In clarifying these notions, we highlight the ultimate and proximate causes of morality and empathy. Empathy has older evolutionary roots in parental care, affective communication and social attachment; morality, on the other hand, is more recent, and relies on both affective and cognitive processes.

Because evolution has tailored the mammalian brain to be sensitive and responsive to the emotional states of others, especially from one’s offspring, and members of one’s social group, empathy has some unfortunate features that can directly conflict with moral behavior, like implicit group preferences. We next consider, using evidence drawn from behavioral, developmental, and functional neuroimaging studies, how empathy can result in immoral judgment and behavior. We then argue that perspective taking is a strategy that can be successfully used to reduce group partiality and expand the circle of empathic concern from the tribe to all humanity. Finally, we conclude that it may be better to refrain from using the slippery concept of empathy and instead make use of more precise constructs such as emotional sharing, empathic concern, and perspective taking.

The Scope of Morality

Morality has been theorized to encompass notions of justice, fairness, and rights, as well as maxims regarding interpersonal relations (Killen & Rutland, 2011). Alternatively, Haidt and Kesebir (2010) contend that morality includes the full array of psychological mechanisms that are active in the moral lives of people across cultures. Rather than stating the content of moral issues (e.g., justice and welfare), this definition specifies the function of moral systems as an interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices, identities that work together to suppress or regulate selfishness and make cooperative social life possible. What seems clear is that, regardless of the definition, a central focus of morality is the judgment of the rightness or wrongness of acts or behaviors that knowingly cause harm to people (see Box 1 for different models of morality).

Box 1. Different models of moral psychology.

Developmental perspectives

In an early theory, provided by Hoffman (1984), egoistic motives are regulated by a socialized affective disposition that is itself intuitive, quick, and not readily accessible to consciousness.

Other theories of moral development, such as Kohlberg’s (1984) and Turiel’s (1983) have focused on moral reasoning, and emphasized cognitive deliberation, decision-making and top-down control. In the Kohlbergian paradigm, fairness, altruism and caring depend on the intervention of explicit, consciously accessible cognitive moral structures to hold in check unreflective egoistic inclinations.

Importantly, for Turiel (1997), the moral-conventional distinction is constructed by a child as a result of empathizing with the victim in one type of transgression but not the other. So when a child sees violations of a moral nature, she/he learns a prescriptive norm against it because she/he imagines the pain or distress such an action would cause to herself/himself. According to social domain theory, children construct different forms of social knowledge, including morality as well as other types of social knowledge, through their social experiences with others (parents, teachers, other adults), peers, and siblings (Smetana, 1995).

Affective and cognitive perspectives

More recent models such as social intuition (Haidt & Kesebir, 2010) or dual-systems (Greene & Haidt, 2002) attempt to infer basic mechanisms of moral judgment assuming that they are unconscious and rapid. In these models, affective responses and social emotions (shame, guilt and empathy) play an essential role.

Evolution and development of morality

Since Darwin (1871), many scholars have argued that morality is an evolved aspect of human nature. Such a claim is well supported when it comes to the role of emotion in moral cognition. It is indeed highly plausible that moral emotions (e.g., guilt and shame) contribute to fitness in shaping decisions and actions when living in complex social groups. In particular, certain emotional responses may have led our ancestors to adopt a Tit-for-Tat strategy (reciprocal altruism). Liking motivates the initiation of altruistic partnerships, anger and moral indignation motivate withdrawal of help, and guilt dissuades from taking more than what one gives (Trivers, 1985). Reinforcement of moral behaviors minimizes criminal behavior and social conflict (Joyce, 2006), and moral norms provide safeguards against possible wellbeing or health infringements (Begossi, Hanazaki, & Ramos, 2004).

Findings from research in moral psychology indicate that moral cognition integrates affective and cognitive processing (Greene & Haidt, 2002). In addition, many moral judgments are surprisingly robust to demographic differences. People are sensitive to some of the same moral principles (e.g., the distinction between permissibility of personal versus impersonal harm) independent of gender, age, ethnicity, and religious views (Young & Saxe, 2011). It is important to note that although this objectivist view seems to be the prevalent contemporary theory, some scholars favor moral relativism. In particular, Prinz (2008) argues that moral values are based on emotional responses, which are inculcated by culture and not hard wired through natural selection. Moreover, it would be misleading to see morality as a direct product of evolution. Morality is also a social institution and many moral codes redirect or even oppose our evolved tendencies such as in-group favoritism (Stewart-Williams, 2010).

A growing body of developmental research demonstrates that the capacity to evaluate others based on their prosocial and antisocial actions operates within the first year of life. It is sensitive to many of the same factors that constrain adults’ social and moral judgments, including the role of mental states and context in distinguishing good and bad behavior (Hamlin, 2014). By their second birthday, children manifest the explicit inclination to help and collaborate with others and begin to show explicit attention to social norms (Robbins & Rochat, 2011). Evolutionary theory and empirical research in developmental science provide strong support for claims that those human capacities for moral evaluation are rooted in basic systems which evolved in the context of cooperation necessary for communal living.

Neural mechanisms underpinning moral cognition

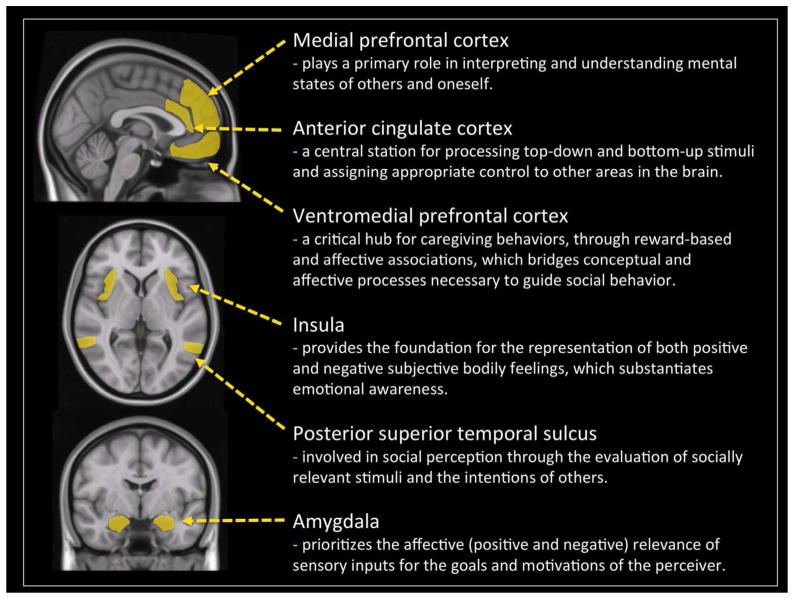

The information processing required for moral cognition is complex. Many neural regions are involved, including areas that are involved in other capacities such as emotional saliency, theory of mind, and decision-making (see Figure 1). Investigations into the neuroscience of morality have begun to shed light on the neural mechanisms underpinning moral cognition (Young & Dungan, 2012). Functional neuroimaging and lesion studies indicate that moral evaluations arise from the integration of cognitive and affective systems, and involve a network of regions comprising the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), amygdala, insula, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (Buckholtz & Marois, 2012; Fumagalli & Priori, 2012; Moll et al., 2007; Shenhav & Greene, 2014; Yoder & Decety, 2014a).

Figure 1.

Network of interconnected regions implicated in moral cognition labeled on sagittal, horizontal, and coronal sections of an average structural MRI scan.

A large part of this neural network is also involved in implicit moral evaluations, that is, when people automatically make moral judgments without being required to do so. For instance, when individuals are shown stimuli depicting intentional interpersonal harm versus accidental harm, heightened neuro-hemodynamic activity is detected (and increased effective connectivity) in regions underpinning emotional saliency (amygdala and insula), understanding mental states (pSTS and mPFC), as well as areas critical for experiencing empathic concern and moral judgment (vmPFC/OFC) (Decety, Michalska, & Kinzler, 2012). Importantly, the timing of the neural processing underpinning these implicit moral computations associated with the perception of harm is extremely fast, as demonstrated by a follow up study employing high-density event-related potentials (Decety & Cacioppo, 2012). Current source density maxima in the right pSTS, as fast as 62 ms post-stimulus, first distinguished intentional vs. accidental harm. Later responses in the amygdala (122 ms) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (182 ms), respectively, were evoked by the perception of intentional (but not accidental) harmful actions, indicative of fast information processing associated with these early stages of moral sensitivity.

It is important to note that the vmPFC is not necessary for affective responses per se (it is not activated by witnessing accidental harm to others), but is critical when affective responses are shaped by conceptual information about specific outcomes (Roy, Shohamy, & Wager, 2012). This region plays a critical role in contextually-dependent moral judgment as demonstrated by functional neuroimaging studies (e.g., Zahn, de Oliveira-Souza, & Moll, 2011). Furthermore, individual differences in empathic concern have been shown to predict the magnitude of response in vmPFC in some moral contexts, but not in others. Specifically, higher empathic concern was related to greater activity in vmPFC in moral evaluations where guilt was induced, but not in moral evaluations where compassion was induced (Zahn, de Oliveira-Souza, Bramati, Garrido, & Moll, 2009). In addition, anatomical lesion and functional dysfunctions of the vmPFC and its reciprocal connections with the amygdala lead to a lack of empathic concern, inappropriate social behavior, a diminished sense of guilt and immoral behavior (Sobhani & Bechara, 2011), and increases utilitarian judgment (Koenigs et al., 2007). Patients with developmental-onset damage to the vmPFC, unlike patients in whom similar lesions occurred during adulthood, endorse significantly more self-serving judgments that broke moral rules or inflicted harm to others (e.g., lying on one’s taxes declaration or killing an annoying boss). Furthermore, the earlier the vmPFC damage, especially before the age of 5 years, the greater likelihood of self-serving moral judgment (Taber-Thomas et al., 2014). In typically developing children, there is increased functional coupling between the vmPFC and amygdala during the evaluation of moral stimuli, in particular interpersonal harm (Decety, Michalska, & Kinzler, 2012). This region seems critical for the acquisition and maturation of a moral competency that goes beyond self-interest to consider the welfare of others. Thus, the vmPFC seems fundamental for both the attainment and growth of moral faculties.

What has become clear from social and clinical neuroscience research is that there is no unique center in the brain for moral judgment. Rather, there are interconnected systems which are not domain-specific, but support more domain-general processing such as affective arousal, attention, intention understanding, and decision-making (Decety & Howard, 2013). For instance, a functional MRI study showed that moral judgment of harm, dishonesty, and sexual disgust are instantiated in dissociable neural systems that are engaged differentially depending on the type of transgression being evaluated (Parkinson et al., 2011). The only overlapping activation across all morally laden scenarios in that study was the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, a region not specifically involved in the decision of wrongness, rather robustly associated with self-referential processing, thinking about other people (i.e., theory of mind) and processing ambiguous information.

Taken together, investigations of the evolutionary, developmental and neural mechanisms of moral cognition yield a strong picture of a constructivist view of morality, an interaction of domain general systems, including executive control/attentional, perspective-taking, decision-making, and emotional processing networks.

Empathy and its Components

Empathy is currently used to refer to more than a handful of distinct phenomena (Batson, 2009). These numerous definitions make it difficult to keep track of which process or mental state the term “empathy” is being used to refer to in any given discussion (Coplan, 2011). Differentiating these conceptualizations is vital, as each refers to distinct psychological processes that vary in their social, cognitive, and underlying neural mechanisms.

Recently, work from developmental and affective and social neuroscience in both animals and humans converge to consider empathy as a multidimensional construct comprising dissociable components that interact and operate in parallel fashion, including affective, motivational and cognitive components (Decety & Jackson, 2004; Decety & Svetlova, 2012). These reflect evolved functions that allow mammalian species to thrive by detecting and responding to significant social events necessary for surviving, reproducing and maintaining well-being (e.g., Decety, 2011; Decety, Norman, Berntson, & Cacioppo, 2012). In this neuroevolutionary framework, the emotional component of empathy reflects the capacity to share or become affectively aroused by others’ emotions (in at least in valence, tone and relatively intensity). The motivational component of empathy (empathic concern) corresponds to the urge of caring for another’s welfare. Finally, cognitive empathy is similar to the construct of perspective taking.

Emotional Sharing

One primary component of empathy, emotional sharing (sometimes referred to as empathic arousal or emotional contagion) plays a fundamental role in generating the motivation to care and help another individual in distress and is relatively independent of mindreading and perspective-taking capacities. Emotion sharing is often viewed as the simplest or a rudimentary form of empathy and can be observed across a multitude of species from birds to rodents and humans (Ben-Ami Bartal, Decety, & Mason, 2011; Edgar, Lowe, & Nicol, 2011). Empirical work with animals and humans demonstrate kin and in-group preferences in the detection and reaction to signs of distress. For instance rodents do not react indiscriminately to other conspecifics in distress. Female mice had higher fear responses (freezing behavior) when exposed to the pain of a close relative than when exposed to the pain of a more distant relative (Jeon et al., 2010). Another investigation found that female mice approaching a dyad member in physical pain led to less writhing from the mouse in pain. These beneficial effects of social approach were seen only when the mouse was a cage mate of the mouse in pain rather than a stranger (Langford et al., 2010). These results replicate previous findings reporting reduced pain sensitivity in mice when interacting with siblings, but no such analgesic effect when mice interact with a stranger (D’Amato & Pavone, 1993). Genetic relatedness alone does not motivate helping as demonstrated by a new study that fostered rats from birth with another strain. Results showed that, as adults, fostered rats helped strangers of the fostering strain but not rats of their own strain (Ben-Ami Bartal et al., 2014). Thus, strain familiarity, even to one’s own strain, is required for the expression of pro-social behavior in rodents. Similarly, early childhood experience with individuals of other racial groups reduces adults’ amygdala response to members of the out-group (Cloutier, Li, & Correll, 2014).

In naturalistic studies, young children with high empathic disposition are more readily aroused vicariously by other’s sadness, pain or distress, but at the same time possess greater capacities for emotion regulation such that their own negative arousal motivates rather than overwhelms their desire to alleviate the other’s distress (Nichols, Svetlova, & Brownell, 2009). Even basic physiological responses to stress (salivary cortisol) have been show to resonate between an individual and observers (Buchanan, Bagley, Stansfield, & Preston, 2012). Despite the general acceptance that emotion contagion is automatic, empirical evidence from both animal (from birds to rodents) and human research shows that many variables affect its induction in an observer. Emotional contagion leads to the experience of emotional similarity, the latter of which is associated with a variety of interpersonal benefits including less conflict and greater cooperation among group members (Barsade, 2002). Overall, the ability to be affected by, and share the emotional state of another facilitates parental care and bonding between individuals from similar group and is moderated by a priori attitudes to out-group members.

Studies using electroencephalography (EEG/ERPs) in children and adults viewing stimuli depicting conspecifics in physical pain, as a tool to examine this basic affective resonance, have documented the elicitation of specific ERP components, including an early automatic attentional salience (N2) and late positive potentials (LPP) that are associated with affective arousal and affective appraisal of the stimuli, respectively (Cheng, Hung, & Decety, 2012; Fan & Han, 2008). Numerous neuroimaging studies in both children (Decety & Michalska, 2010) and adults (Lamm, Decety, & Singer, 2011) have reliably demonstrated that when individuals are exposed to facial expressions of pain, sadness, or emotional distress, or even when they imagine others in pain, brain regions involved in the first-hand experience of pain (aka the pain matrix or salience network) are activated. These regions include the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the anterior midcingulate cortex (aMCC), anterior insula, supplementary motor area, amygdala, somatosensory cortex, and periaqueductal gray area (PAG) in the brainstem. Thus observing another individual in distress or in pain induces a visceral arousal in the perceiver by eliciting neural response in a salience network that relates to interoceptive-autonomic processing (Seeley et al., 2007) and triggers defensive and protective behaviors.

Empathic Concern

Another component of the construct of empathy is empathic concern. All mammals depend on other conspecifics for survival and reproduction, particularly parental care, which is a necessary for infant survival and development (Decety, Norman, Berntson, & Cacioppo, 2012). The level of care varies by species, but the underlying neural circuitry for responding to infants (especially signals of vulnerability and need) is universally present and highly conserved across species. Animal research demonstrates that being affected by others’ emotional states, an ability integral to maintaining the social relationships important for survival, is organized by basic neural, autonomic, and neuroendocrine systems subserving attachment-related processes, which are implemented in the brainstem, preoptic area of the thalamus, basal ganglia, paralimbic areas, as well as the autonomic nervous system (Panksepp, 1998). Converging evidence from animal behavior (Insel & Young, 2001), neuroimaging studies in healthy individuals, and lesion studies in neurological patients (Shamay-Tsoory, 2009) demonstrates that caring for others employs a large array of systems neural mechanisms, extending beyond the cortex, including the amygdala, brainstem, hypothalamus, insula, ACC, and orbitofrontal cortex (Preston, 2013). It also involves the autonomic nervous system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and endocrine and hormonal systems (particularly oxytocin and vasopressin) that regulate bodily states, emotion, and social sensitivity. These systems underlying attachment appear to exploit the strong, established physical pain and reward systems, borrowing aversive signals associated with pain to indicate when relationships are threatened (Eisenberger, 2011).

Importantly, this motivation to care is both deeply rooted in our biology and very flexible. People can feel empathic concern for a wide range of targets when cues of vulnerability and need are highly salient, including nonhumans, and in our western culture particularly pet animals like puppies (Batson, 2012). Neural regions involved in perceiving the distress of other humans are similarly recruited when witnessing the distress of domesticated animals (Franklin et al., 2013).

Perspective-taking

The third component of empathy, perspective taking refers to the ability to consciously put oneself into the mind of another individual and imagine what that person is thinking or feeling. It has been linked to social competence and social reasoning (Underwood & Moore, 1982) and can be used as a strategy for reducing group biases. A substantial body of behavioral studies has documented that affective perspective taking is a powerful way to elicit empathy and concern for others (Batson, 2012; van Lange, 2008), and reduce prejudice and intergroup bias. For instance, taking the perspective of an out-group member leads to a decrease in the use of explicit and implicit stereotypes for that individual, and to more positive evaluations of that group as a whole (Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000). Something of this sort occurred, among the rescuers of Jews during the Second World War in Europe. A careful look at data collected by Oliner and Oliner (1988) suggests that involvement in rescue activity frequently began with concern for a specific individual or individuals for whom compassion was felt—often individuals known previously. This initial involvement subsequently led to further contact and rescue activity, and to a concern for justice, that extended well beyond the bounds of the initial empathic concern. Assuming the perspective of another (like being in a wheelchair) brings about changes in the way we see the other, and these changes generalize to people similar to them, notably members of the same social groups to which they belong (Castano, 2012). Some studies have documented long-lasting effects of such interventions. For instance, Sri Lankan Singhalese participants expressed enhanced empathy toward a group of individuals that they had been in a long term and violent conflict with (the Tamils) even a year after participating in a 4-day intergroup workshop (Malhotra & Liyanage, 2005).

Adopting the perspective of another person, in particular someone from another social group, is cognitively demanding and hence requires additional attentional resources and working memory, thus taxing executive function. Interestingly, neuroscience research demonstrates that when individuals adopt the perspective of another, neural circuits common to the ones underlying first-person experiences are activated as well (Decety, 2005; Lamm, Meltzoff & Decety, 2010; Jackson, Brunet, Meltzoff, & Decety, 2006; Ruby & Decety, 2004). However, taking the perspective of another produces increased activation in regions of the prefrontal cortex that are implicated in working memory and executive control. In a neuroimaging study, participants watched video-clips featuring patients undergoing painful medical treatment, and were asked to either put themselves explicitly in the shoes of the patient (imagine self), or to focus on the patient’s feelings and affective expressions (imagine other). Explicitly projecting oneself into an aversive situation led to higher personal distress, which was associated with enhanced activation in the amygdala and ACC – whereas focusing on the emotional and behavioral reactions of another in distress was accompanied by higher empathic concern, lower personal distress, increased activity in the executive attention network, vmPFC, and reduced amygdala response (Lamm, Batson, & Decety, 2007).

Distinguishing between these three components of empathy is far from being only a theoretical debate. It has implications for research design and interpretation as well. For instance, a recent study by Mößle and colleagues (2014) examined the link between violent media consumption and aggressive behavior in a very large sample of children and reported that in boys (and not in girls) “empathy” mediated the relationship between media consumption and aggressive behavior. The measure of empathy employed lumped together items that assess feelings of concern for the other but also some aspects that we would categorize as reflecting personal distress. It would have been useful to separate these two as their neural and cognitive mechanisms are quite distinct. A similar reasoning can be useful in the study of morality.

The Unfortunate Features of Empathy

As empathic concern and emotional sharing has evolved in the context of parental care and group living, it has some unfortunate features that can conflict with moral behavior. It is well established that the mere assignment of individuals to arbitrary groups elicits evaluative preferences for in-group relative to out-group members, and this impacts empathy. In one behavioral study, participants were assigned to artificial groups and required to perform pain intensity judgments of stimuli depicting bodily injuries from self, in-group, and out-group perspectives. Participants rated the stimuli as more painful when they had to adopt the perspective of an in-group member as compared to their own perspective, while the out-group perspective did not induce different responses to the painful stimuli as compared to the self-perspective. Moreover, the ratings differences between the painful and non-painful pictures were greater for in-group than for out-group members (Montalan, Lelard, Godefroy, Mouras, 2012).

Although empathic concern is one of the earliest social emotional competencies that develops (Davidov, Zahn-Waxler, Roth-Hanania, & Knafo, 2013), children do not display empathy and concern toward all people equally. Instead they show bias towards individuals and members of groups with which they identify. For instance 2-year old children display more empathy-related behaviors toward their mother than toward unfamiliar individual. In line with the in-group hypothesis, 8-year-old children were more likely to be emotionally reactive toward their in-group members compared with members of the out-group, and dispositional empathy (as well as social anxiety) was positively correlated with group identification (Masten, Gillen-O’Neel, & Spears-Brown, 2010). Moreover, children (aged 3–9 years) view social categories as marking patterns of intrinsic interpersonal obligations; that is, they view people as intrinsically obligated only to their own group members, and consider within-group harm as wrong regardless of explicit rules, but they view the wrongness of between-group as contingent on the presence of such rules (Rhodes & Chalik, 2013). These results regarding the non-obligatory nature of between group harm contradict the prevalent notion from social domain theory that moral transgressions about harm are unalterable (and contextually independent) from as young as preschool age (Smetana, 1981).

In a recent study, British Caucasian participants were read a summary of the atrocities committed by Caucasian British against the African slaves and asked about their guilt toward these actions and their categorization of the relationship between British and African nations. Opposing a commonsense view that conceptualizing nations as a single, shared humanity would predict greater remorse towards these actions, the individuals who viewed the British and African nations as two separate races felt greater guilt over historic transgressions and had lesser expectations of forgiveness (Morton & Postmes, 2011). Moreover, in another study, people’s relative levels of economic well-being were found to shape their beliefs about what is right or wrong. In that study, upper-class individuals were more likely to make calculated, dispassionate moral judgments in dilemmas in which utilitarian choices were at odds with visceral moral intuitions (Cote, Piff, & Willer, 2013). In this way, the lower concern of upper-class individuals ironically led them to make moral decisions that were more likely to maximize the greatest good for the greatest number. In short, straightforward predictions between empathic concern and morality are not possible and appear to be governed by contextual influences.

Further evidence from studies with adults suggests that although empathic concern does not necessarily change notions of fairness (e.g., what is the just action in a certain situation), it does change the decision an individual will make. In one such study (Batson, Klein, Highberger, & Shaw, 1995), college students required to assigning a good and bad task to two individuals overwhelmingly endorsed random assignment (i.e., a coin flip) as the most fair means for deciding who would be assigned with the bad task. However, when asked to consider the feelings of a worker who had recently suffered hardship, students readily offered the good task to the worker, rather than using random assignment.

Recent investigations from social and affective neuroscience have documented that the neural network implicated in empathy for the pain of others is either strengthened or weakened by interpersonal variables, implicit attitudes, and group preferences. Activity in the pain neural network is significantly enhanced when individuals view or imagine their loved-ones in pain compared to strangers (Cheng, Chen, Lin, Chou, & Decety, 2010). Empathic arousal is moderated by a priori implicit attitudes toward conspecifics. For example, study participants were significantly more sensitive to the pain of individuals who had contracted AIDS as the result of a blood transfusion as compared to individuals who had contracted AIDS as the results of their illicit drug addiction (sharing needles), as evidenced by higher pain sensitivity ratings and greater hemodynamic activity in the ACC, insula, and PAG, although the intensity of pain on the facial expressions was strictly the same across all videos (Decety, Echols, & Correll, 2009). Another study found evidence for a modulation of empathic neural responses by racial group membership (Xu, Zuo, Wang, & Han, 2009). Notably, the response in the ACC to perception of others in pain decreased remarkably when participants viewed faces of racial out-group members relative to racial in-group members. This effect was comparable in Caucasian and Chinese subjects and suggests that modulations of empathic neural responses by racial group membership are similar in different ethnic groups. Another study demonstrated that the failures of an in-group member are painful, whereas those of a rival out-group member gives pleasure—a feeling that may motivate harming rivals (Cikara, Botvinick, & Fiske, 2011).

All these representative behavioral, developmental and functional neuroimaging studies clearly demonstrate that distinct components of empathy are modulated by both bottom-up and top-down processes such as those involved in group membership, and this can affect prosocial and moral behaviors.

Relationships between Empathy and Moral Judgments

The precise ways in which empathy contributes to moral judgment remain debated, but in addition to influencing moral evaluation, it might also play an important developmental role, leading to the aversion to violent actions without necessarily empathizing with the victims of such actions (Miller, Hannikainen & Cushman, 2014). One paradigm often used in psychological and some neuroscience studies of moral judgment is a thought experiment borrowed from philosophy, the Trolley Dilemma (e.g., Foot, 1967; Thomson, 1976). Participants are told about an out of control trolley headed down a track to which six persons are tied; there is an alternate track to which one individual is tied. Subjects are then given an option of diverting the trolley: they can pull a lever and the trolley will be diverted to the alternate track, killing the one individual and saving the group. This decision is relatively easy to make and the majority of participants will choose to divert the trolley. However, another option is presented, rather than pulling a lever, they have to either let the six die or they can push a large man in front of the trolley, again, sacrificing the one to save the group. This decision, for the majority of participants, is not comfortable, in fact, most refuse to push the man. This classic thought problem, comparing impersonal and personal moral decision-making, referred to as utilitarian judgment, has led to a great deal of inquiry about the nature of individuals who will push the large man in front of the trolley.

Are individuals who make utilitarian judgments in personal situations more rational and calculating, or are they simply colder and less averse to harming others? Support for a link between empathy and moral reasoning is given by studies demonstrating that low levels of dispositional empathic concern predict utilitarian moral judgment, in some situations (e.g., Gleichgerrcht, & Young, 2013). A functional neuroimaging study recently examined the neural basis of such indifference to harming while participants were engaged in moral judgment of dilemmas (Wiech et al., 2013). A tendency towards counterintuitive impersonal utilitarian judgment was associated both with ‘psychoticism’ (or psychopathy), a trait linked with a lack of empathic concern and antisocial tendencies, and with ‘need for cognition’, a trait reflecting preference for effortful cognition. Importantly, only psychoticism was also negatively correlated with activation in the vmPFC during counterintuitive utilitarian judgments. These findings suggest that when individuals reach highly counterintuitive utilitarian conclusions, it does not need to reflect greater engagement in explicit moral deliberation. It may rather reveal a lack of empathic concern, and diminished aversion to harming others. Lesions of the orbitofrontal cortex (including the vmPFC) have been associated with increased utilitarian choices in highly conflicting moral dilemmas more often than control subjects, opting to sacrifice one person’s life to save a number of other individuals (Koenigs et al., 2007).

Additional support for a link between empathic concern and morality can be found in neuroimaging studies with individuals with psychopathy. Psychopaths are characterized by a lack of empathic concern, guilt and remorse, and consistently show abnormal anatomical connectivity and functional response in the vmPFC (Motzkin, Newman, Kiehl, & Koenigs, 2011). For instance, when individuals with psychopathy were shown pictures of physical pain and asked to imagine how another person would feel in these scenarios, they exhibited an atypical pattern of brain activation and effective connectivity between the anterior insula and amygdala with the vmPFC (Decety, Chen, Harenski, & Kiehl, 2013; Decety, Skelly, & Kiehl, 2013). The response in the amygdala and insula was inversely correlated with their scores on psychopathy checklist revised (Psychopathy Check List- Revised, PCL-R) factor 1, which accounts for the interpersonal/affective deficits. Importantly, and contrary to popular opinion, individuals with psychopathy do seem to make the “cognitive” distinction between moral wrongs and other types of wrongs. For instance, a study with a forensic population examining the extent to which incarcerated offenders with varying degrees of psychopathy could distinguish between moral and conventional transgressions relative to each other and to non-incarcerated healthy controls, found that psychopathy as a whole did not predict the ability to understand what is morally wrong (Aharoni, Sinnott-Armstrong, & Kiehl, 2012). However, the affective facet of psychopathy (PCL-R Factor 1) predicted reduced performance on the moral vs. conventional transgression task, which supports the notion that emotion contributes to moral cognition.

In summary, neuroimaging experiments, lesions studies, and studies on psychopathy document the critical role of the vmPFC in moral decision-making and empathic concern, as well as the importance of this region in processing aversive emotions that arise from perceiving or imagining harmful intentions. Such information is processed extremely rapidly as demonstrated by high-density EEG/ERP recordings in individuals viewing intentional interpersonal harm (Decety & Cacioppo, 2012; Yoder & Decety, 2014b), and is factored in when making moral judgments.

Extending Empathic Concern Outside the Tribe

Even the most advanced forms of empathy in humans are built on more basic forms and remain connected to affective communication, social attachment, and parental care, the neurobiological mechanisms of which are highly conserved across mammalian species (Decety, 2011). Empathic concern evolved in the context of parental care and group living, yielding a variety of group biases that can certainly affect our moral behavior. Interestingly, both empathic concern and moral decision making require involvement of the orbitofrontal/ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a region reciprocally connected with ancient affective systems in brainstem, amygdala, hypothalamus, that bridges conceptual and affective processes and that is necessary to guide moral behavior and decision-making. This region, across species, is a critical hub for caregiving behavior, particularly parenting through reward-based and affective associations (Parsons et al., 2013). Thus, care-based morality piggybacks on older evolutionary motivational mechanisms associated with parental care. This explains why empathy is not a direct avenue to morality and can at times be a source of immoral action by favoring self-interest.

In humans as well as in non-human animals, empathic concern and prosocial behavior are modulated by the degree of affiliation and are extended preferentially towards in-group members and less often toward unaffiliated others (Echols & Correll, 2012). Yet humans can and often do act pro-socially towards strangers and extend concern beyond kin or own social group. Humans have created meta-level symbolic social structures for upholding moral principles to all humanity, such as Human Rights and the International Criminal Court. In the course of history, people have enlarged the range of beings whose interests they value as they value their own, from direct offspring, to relatives, to affiliates, and finally to strangers (Singer, 1981). Thus, nurture is not confined to the dependent young of one’s own kin system, but also to current and future generations. Such a capacity to help and care for unfamiliar individuals is often viewed as complex behavior that depends on high cognitive capacities, social modeling, and cultural transmission (Levine, Prosser, Evans, & Reicher, 2005).

It has been argued that moral progress involves expanding our concern from the family and the tribe to humanity as a whole. Yet it is difficult to empathize with seven billion strangers, or to feel toward someone one never met the degree of concern one feels for one’s own baby, or a friend. One of the recent “inventions” that, according to Pinker (2011) contributed to expanding empathy is the expansion of literacy during the humanitarian revolution in the 18th century. In the epistolary novel, the story unfolds in a character’s own words, exposing the character’s thoughts and feelings in real time rather than describing them from the distancing perspective of a disembodied narrator. Preliminary research suggests that reading literary fiction temporarily improves the capacity to identify and understand others’ subjective affective and cognitive mental states (Kidd & Castano, 2013). Studies conducted by Bal and Veltkamp (2013) investigated the influence of fictional narrative experience on empathy over time, and indicate that self-reported empathic skills significantly changed over the course of one week for readers of a fictional stories. Another line of research implies that arts intervention –training in acting– leads to growth in empathy and theory of mind (Goldstein & Winner, 2012). Thus, mounting evidence seems to indicate that reading, language, the arts, and the media provide rich cultural input which triggers internal simulation processes (Decety & Grèzes, 2006), and leads to the experience of emotions and influencing both concern and caring for others.

Is Empathy a Necessary Concept?

To wrap up on a provocative note, it may be advantageous for the science of morality, in the future, to refrain from using the catch-all term of empathy, which applies to a myriad of processes and phenomena, and as a result yields confusion in both understanding and predictive ability. In both academic and applied domains such medicine, ethics, law and policy, empathy has become an enticing, but muddy notion, potentially leading to misinterpretation. If ancient Greek philosophy has taught us anything, it is that when a concept is attributed with so many meanings, it is at risk for losing function. Emotional sharing (or affective arousal), empathic concern, and perspective taking are more precise in their scope and allow for generative theories about their relations with moral cognition. Each of these emotional, motivational, and cognitive facets of empathy has a different relationship with morality, and are swayed by both social context and interpersonal relationships. An analogy can be made with the umbrella term of executive function in cognitive and developmental sciences. Following a similar call (Miyake et al., 2000) for dissociable processes in this concept of executive function, there is greater utility and accuracy in studying shifting, inhibiting and updating (working memory). Thus, if everyone agrees that empathy covers three distinct (not necessarily mutually exclusive) sets of processes, why not drop the usage of this umbrella concept?

Acknowledgments

The writing of this article was supported by grants from the John Templeton Foundation (The Science of Philanthropy Initiative and Wisdom Research) and from NIH (1R01MH087525-01A2; MH084934-01A1) to Dr. Jean Decety. We thank three anonymous reviewers and the Editor for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

References

- Aharoni E, Sinnott-Armstrong W, Kiehl KA. Can psychopathic offenders discern moral wrongs? A new look at the moral/conventional distinction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:484–497. doi: 10.1037/a0024796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal PM, Veltkamp M. How does fiction reading influence empathy? An experimental investigation of the role of emotional transportation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsade SG. The ripple effect: emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2002;47:644–675. [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD. These things called empathy: Eight related but distinct phenomena. In: Decety J, Ickes W, editors. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge MA: MIT press; 2009. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD. The empathy-altruism hypothesis: Issues and implications. In: Decety J, editor. Empathy – From Bench to Bedside. Cambridge MA: MIT Press; 2012. pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, Klein TR, Highberger L, Shaw LL. Immorality from empathy-induced altruism: When compassion and justice conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:1042–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Begossi A, Hanazaki N, Ramos R. Food chain and the reasons for fish food taboos among Amazonian and Atlantic forest fishers. Ecological Applications. 2004;14:1334–1343. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ami Bartal I, Decety J, Mason P. Empathy and pro-social behavior in rats. Science. 2011;334:1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.1210789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ami Bartal I, Rodgers DA, Bernardez Sarria MS, Decety J, Mason P. Prosocial behavior in rats is modulated by social experience. eLife. 2014;3:e1385. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, Bagley SL, Stansfield RB, Preston SD. The empathic, physiological resonance of stress. Social Neuroscience. 2012;7:191–201. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2011.588723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholtz JW, Marois R. The roots of modern justice: cognitive and neural foundations of social norms and their enforcement. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15:655–661. doi: 10.1038/nn.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano E. Antisocial behavior in individuals and groups: an empathy-focused approach. In: Deaux K, Snyder M, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 419–445. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Chen CY, Lin CP, Chou KH, Decety J. Love hurts: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2010;51:923–929. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Hung A, Decety J. Dissociation between affective sharing and emotion understanding in juvenile psychopaths. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:623–636. doi: 10.1017/S095457941200020X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cikara M, Botvinick MM, Fiske ST. Us versus them: social identity shapes responses to intergroup competition and harm. Psychological Science. 2011;22:306–313. doi: 10.1177/0956797610397667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier J, Li T, Correll J. The impact of childhood experience on amygdala response to perceptually familiar black and white faces. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2014 doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00605. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan A. Understanding empathy. In: Coplan A, Goldie P, editors. Empathy: Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cote S, Piff PK, Willer R. For whom do the ends justify the means? Social class and utilitarian moral judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104:490–503. doi: 10.1037/a0030931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. 1874. London: John Murray; 1871. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato FR, Pavone F. Endogenous opioids: A proximate reward mechanism for kin selection? Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1993;60:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(93)90768-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, Zahn-Waxler C, Roth-Hanania R, Knafo A. Concern for others in the first year of life: theory, evidence, and avenues for research. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7:126–131. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal F. The Age of Empathy. New York: Crown Publishing Group; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Decety J. Perspective taking as the royal avenue to empathy. In: Malle BF, Hodges SD, editors. Other Minds: How Humans Bridge the Divide between Self and Others. New York: Guilford Publishers; 2005. pp. 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Decety J. The neuroevolution of empathy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1231:35–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Cacioppo S. The speed of morality: a high-density electrical neuroimaging study. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2012;108:3068–3072. doi: 10.1152/jn.00473.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Jackson PL. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2004;3:71–100. doi: 10.1177/1534582304267187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Chen C, Harenski CL, Kiehl KA. An fMRI study of affective perspective taking in individuals with psychopathy: imagining another in pain does not evoke empathy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2013;7:489. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Echols SC, Correll J. The blame game: The effect of responsibility and social stigma on empathy for pain. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;22:985–997. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Grèzes J. The power of simulation: Imagining one’s own and other’s behavior. Brain Research. 2006;1079:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Howard L. The role of affect in the neurodevelopment of morality. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ. Neurodevelopmental changes in the circuits underlying empathy and sympathy from childhood to adulthood. Developmental Science. 2010;13:886–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ, Kinzler KD. The contribution of emotion and cognition to moral sensitivity: A neurodevelopmental study. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;22:209–220. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Norman GJ, Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT. A neurobehavioral evolutionary perspective on the mechanisms underlying empathy. Progress in Neurobiology. 2012;98:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Skelly LR, Kiehl KA. Brain response to empathy-eliciting scenarios in incarcerated individuals with psychopathy. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:638–645. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Svetlova M. Putting together phylogenetic and ontogenetic perspectives on empathy. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012;2:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echols S, Correll J. It’s more than skin deep: Empathy and helping behavior across social groups. In: Decety J, editor. Empathy: from Bench to Bedside. Cambridge MA: MIT Press; 2012. pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar JL, Lowe JC, Nicol CJ. Avian maternal response to chick distress. Proceedings of the Royal Society, B. 2011;1721:3129–3134. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger N. Why rejection hurts: What social neuroscience has revealed about the brain’s response to social rejection. In: Decety J, Cacioppo JT, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Social Neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 586–598. [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Han S. Temporal dynamic of neural mechanisms involved in empathy for pain: an event-related brain potential study. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:160–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foot P. The problem of abortion and the doctrine of the double effect in virtues and vices. Oxford Review. 1967;5 [Google Scholar]

- Franklin RG, Nelson AJ, Baker M, Beeney JE, Vescio TK, Lenz-Watson A, Adams RA. Neural responses to perceiving suffering in humans and animals. Social Neuroscience. 2013;8(3):217–227. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2013.763852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli M, Priori A. Functional and clinical neuroanatomy of morality. Brain. 2012;135:2006–2021. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky AD, Moskowitz GB. Perspective-taking: decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility and in-group favoritism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:708–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleichgerrcht E, Young L. Low levels of empathic concern predict utilitarian moral judgment. PLoS One. 2013;4:e60418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Winner E. Enhancing empathy and theory of mind. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2012;13:19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Greene J, Haidt J. How (and where) does moral judgment work? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2002;12:517–523. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)02011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, Kesebir S. Morality. In: Fiske S, Gilbert D, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. 5. Hobeken, NJ: Wiley; 2010. pp. 797–832. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin JK. The origins of human morality: Complex socio-moral evaluations by pre-verbal infants. In: Decety J, Christen Y, editors. New Frontiers in Social Neuroscience. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 165–188. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Empathy, its limitations, and its role in a comprehensive moral theory. In: Gewirtz J, Kurtines W, editors. Morality, Moral Development, and Moral Behavior. New York: Wiley; 1984. pp. 283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Young LJ. The neurobiology of attachment. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:129–136. doi: 10.1038/35053579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PL, Brunet E, Meltzoff AN, Decety J. Empathy examined through the neural mechanisms involved in imagining how I feel versus how you feel pain: An event-related fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:752–761. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon D, Kim S, Chetana D, Jo D, Ruley HE, Rabah D, Kinet JP, Shin HS. Observational fear learning involves affective pain system and Ca1.2 CA channels in ACC. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13:482–488. doi: 10.1038/nn.2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce R. The Evolution of Morality. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd DC, Castano E. Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science. 2013;342:377–380. doi: 10.1126/science.1239918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Rutland A. Children and Social Exclusion: Morality, Prejudice, and Group Identity. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 480–481. [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs M, Young L, Adolphs R, Tranel D, Cushman F, Hauser M, Damasio AR. Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgments. Nature. 2007;446:908–911. doi: 10.1038/nature05631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg L. Essays in Moral Development: Vol. 2. The Psychology of Moral Development. New York: Harper & Row; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm C, Batson CD, Decety J. The neural basis of human empathy: Effects of perspective-taking and cognitive appraisal. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19:42–58. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm C, Decety J, Singer T. Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm C, Meltzoff AN, Decety J. How do we empathize with someone who is not like us? Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2010;2:362–376. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford DJ, Tuttleb AH, Brown K, Deschenes S, Fischer DB, Mutso A, Root KC, Sotocinal SG, Stern MA, Mogil JS, Sternberg WF. Social approach to pain in laboratory mice. Social Neuroscience. 2010;5:163–170. doi: 10.1080/17470910903216609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M, Prosser A, Evans D, Reicher S. Identity and emergency intervention: how social group membership and inclusiveness of group boundaries shape helping behavior. Personality and Social Psychological Bulletin. 2005;31:443–453. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra D, Liyanage S. Long-term effects of peace workshops in protracted conflicts. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2005;49:908–924. [Google Scholar]

- Masten CL, Gillen-O’Neel C, Spears Brown C. Children’s intergroup empathic processing: The roles of novel ingroup identification, situational distress, and social anxiety. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2010;106:115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RM, Hannikainen IA, Cushman FA. Bad actions or bad outcomes? Differentiating affective contributions to the moral condemnation of harm. Emotion. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0035361. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobes” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology. 2000;41:49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J, De Oliveira-Souza R, Garrido GJ, Bramati IE, Caparelli EMA, Paiva MLMF, Zahn R, Grafman J. The self as a moral agent: Linking the neural bases of social agency and moral sensitivity. Social Neuroscience. 2007;2:336–352. doi: 10.1080/17470910701392024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalan B, Lelard T, Godefroy O, Mouras H. Behavioral investigation of the influence of social categorization on empathy for pain: a minimal group paradigm study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3:389. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton TA, Postmes T. Moral duty or moral deference? The effects of perceiving shared humanity with the victims of ingroup perpetrated harm. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;41:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Mößle T, Kliem S, Rehbein F. Longitudinal effects of violent media usage on aggressive behavior – The significance of empathy. Societies. 2014;4:105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Motzkin JC, Newman JP, Kiehl KA, Koenigs M. Reduced prefrontal connectivity in psychopathy. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:17348–17357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4215-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols SR, Svetlova M, Brownell CA. The role of social understanding and empathic disposition in young children’s responsiveness to distress in parents and peers. Cognition Brain Behavior. 2009;13:449–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliner SP, Oliner PM. The Altruistic Personality: Rescuers of Jews in Nazi Europe. New York: Free Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. Affective Neuroscience. Oxford University Press; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson C, Sinnott-Armstrong W, Koralus PE, Mendelovici A, McGeer V, Wheatley T. Is morality unified? Evidence that distinct neural systems underlie moral judgments of harm, dishonesty, and disgust. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23:3162–3180. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons CE, Stark EA, Young KS, Stein A, Kringelbach ML. Understanding the human parental brain: A critical role of the orbitofrontal cortex. Social Neuroscience. 2013;8:525–543. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2013.842610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinker S. The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence has Declined. New York: Penguin Group; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Preston SD. The origins of altruism in offspring care. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;4:1–37. doi: 10.1037/a0031755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz JJ. The Emotional Construction of Morals. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, Chalik L. Social categories as markers of intrinsic interpersonal obligations. Psychological Science. 2013;24:999–1006. doi: 10.1177/0956797612466267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin J. The Empathic Civilization: The Race to Global Consciousness in a World in Crisis. New York: Penguin Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins E, Rochat P. Emerging signs of strong reciprocity in human ontogeny. Frontiers in Psychology. 2011;2:353. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M, Shohamy D, Wager TD. Ventromedial prefrontal-subcortical systems and the generation of affective meaning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012;16:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby P, Decety J. How would you feel versus how do you think she would feel? A neuroimaging study of perspective taking with social emotions. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16:988–999. doi: 10.1162/0898929041502661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Greicius MD. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory S. Empathic processing: Its cognitive and affective dimensions and neuroanatomical basis. In: Decety J, Ickes W, editors. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2009. pp. 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- Shenhav A, Greene JD. Integrative moral judgment: Dissociating the roles of the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:4741–4749. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3390-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer P. The Expanding Circle: Ethics and Sociobiology. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana J. Preschool children’s conceptions of moral and social rules. Child Development. 1981;52:1333–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Morality in context: Abstractions, ambiguities, and applications. In: Vasta R, editor. Annals of Child Development. 10 . London: Jessica Kinglsey; 1995. pp. 83–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sobhani M, Bechara A. A somatic marker perspective of immoral and corrupt behavior. Social Neuroscience. 2011;6:640–652. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2011.605592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart-Williams S. Darwin, God, and the Meaning of Life. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Taber-Thomas BC, Asp EW, Koenigs M, Sutterer M, Anderson SW, Tranel D. Arrested development: early prefrontal lesions impair the maturation of moral judgment. Brain. 2014;137:1254–1261. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson JJ. Killing, letting die, and the trolley problem. The Monist. 1976;59:204–17. doi: 10.5840/monist197659224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivers RL. Social Evolution. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin Cummings Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The Development of Social Knowledge: Morality and Convention. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. Beyond particular and universal ways: Context for morality. New Directions for Child Development. 1997;76:87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood B, Moore B. Perspective-taking and altruism. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;91:143–173. [Google Scholar]

- van Lange PAM. Does empathy triggers only altruistic motivation: How about selflessness and justice? Emotion. 2008;8:766–774. doi: 10.1037/a0013967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiech K, Kahane G, Shackel N, Farias M, Savulescu J, Tracey I. Cold or calculating? Reduced activity in the subgenual cingulate cortex reflects decreased emotional aversion to harming in counterintuitive utilitarian judgment. Cognition. 2013;126:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Zuo X, Wang &, Han S. Do you feel my pain? Racial group membership modulates empathic neural responses. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:8525–8529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2418-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder KJ, Decety J. The good, the bad, and the just: Justice sensitivity predicts neural response during moral evaluation of actions performed by others. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014a;34(12):4161–4166. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4648-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder KJ, Decety J. Spatiotemporal neural dynamics of moral judgments: A high-density EEG/ERP study. Neuropsychologia. 2014b doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.05.022. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Dungan J. Where in the brain is morality? Everywhere and maybe nowhere. Social Neuroscience. 2012;7(1–2):1–10. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2011.569146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Saxe R. Moral universals and individual differences. Emotion Review. 2011;3:323–324. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn R, de Oliveira-Souza R, Bramati I, Garrido G, Moll J. Subgenual cingulate activity reflects individual differences in empathic concern. Neuroscience Letters. 2009;457:107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn R, de Oliveira-Souza R, Moll J. The neuroscience of moral cognition and emotion. In: Decety J, Cacioppo JT, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Social Neuroscience. 2011. pp. 477–490. [Google Scholar]