Abstract

Cultural contexts influence the ways individuals interpret and experience functional losses associated with post-polio sequelae. Using in-depth multiple interview case studies from two National Institute on Aging projects, the concept of “biographies” is presented to place the individuals’ polio-related experiences within the context of their lives. Two major cultural contexts shape the construction of polio biographies: normative life course expectations and developmental tasks; and traditions associated with polio recovery and rehabilitation. The authors identify key dimensions of personal concern among polio survivors that can be used as entrance points for effective clinical intervention and to promote treatment compliance.

Clinicians have observed that cultural values and beliefs are important in shaping how patients define and experience their disabilities. However, the link from this clinical observation to an understanding of the cultural dimensions of the post-polio experience has not been made in the literature.

We describe the wider cultural contexts that influence the ways individuals interpret and experience post-polio sequelae. The goal is to extend these insights to suggest practical, clinical applications. Data from in-depth multiple interview case studies are used to illustrate how adults present their polio-related experiences within the context of their biographies. The case studies focus on personal interpretations of new functional losses among clinic, support group, and community-based polio survivors in two metropolitan areas.1–5

Anthropology, the cross-cultural and holistic social science, analyzes how the interaction between cultural values and beliefs, social relations, and historical changes affects patterns of daily life and personal experience. The task of anthropologists with interests in rehabilitation and aging is to clarify how the social consequences of disability are constructed in different societies and experienced by individuals over the life span. The issue of “human vulnerability” is an important focus in cross-cultural studies, because it serves to underscore the key values and beliefs that define a particular culture. In American society, the social consequences of vulnerability and dependence, central aspects of living with a disability, challenge our most basic cultural values and beliefs about the role of the individual in society.6 Thus, attention will be given to core cultural values and beliefs, such as the work ethic, that guide all of our lives.

Cultural Patterning

Major findings from the ethnographic study of polio survivors at mid and late life indicate two themes. First, decisions about current disability-related issues are infused with broader concerns about personal identity and the fulfillment of personal and cultural ideals, values, and expectations. Second, early life disability experiences continue to be important in later life. A person’s interpretations and responses regarding the onset of new functional losses cannot be understood apart from these larger cultural contexts.

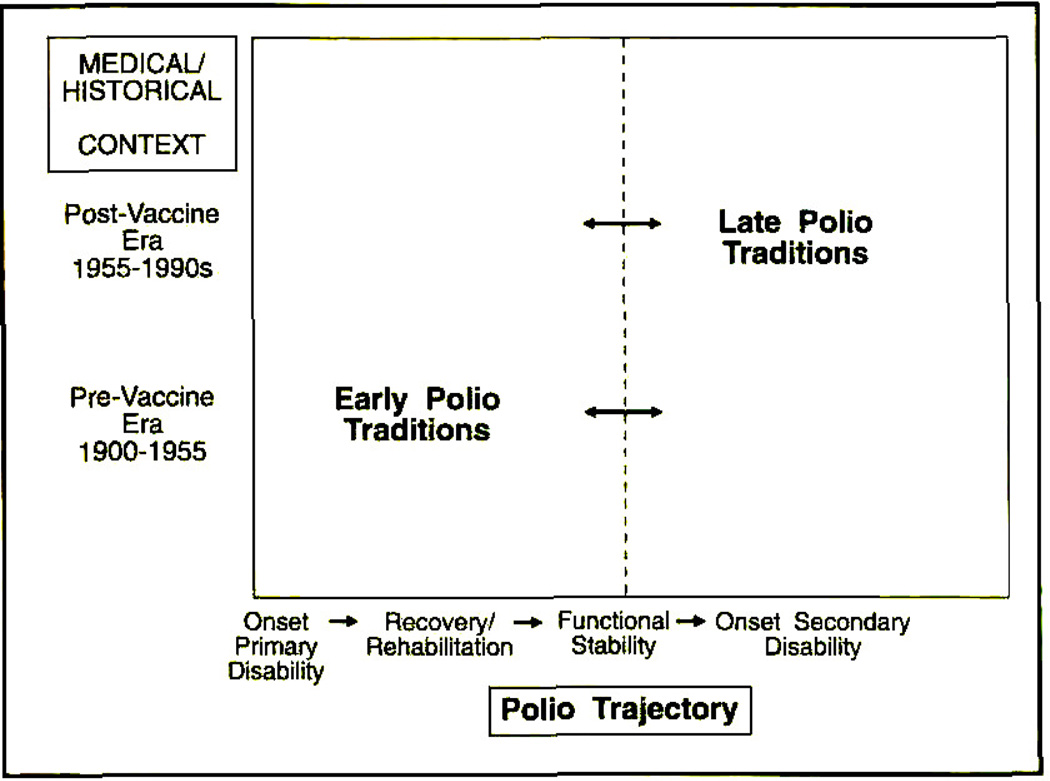

A set of schematic figures will provide a framework for how historical and cultural contexts influence individual responses to new functional losses. Figure 1 illustrates the interaction of the polio disease trajectory in the medical/historical context. Polio trajectory refers to the natural history of polio: acute infection, recovery/rehabilitation, functional stability, and the onset of secondary disabilities. The medical/historical context points to changes that have occurred in the medical management of polio and the changing social perceptions of disability in the 1970s and 1980s.

Fig 1.

Changing cultural contexts.

The intersection of the polio trajectory and the medical/historical context has resulted in two distinct but interacting polio traditions. Early polio traditions, the cultural values and ideals specific to the pre-vaccine years, developed when disabilities were viewed largely as a medical problem. Polio survivors were expected to be “good patients,” comply with treatment recommendations, and assimilate into the mainstream of American life.

The onset of new symptoms challenges individuals to reexamine earlier cultural expectations, beliefs, and ideals. Later polio traditions are developing in response to the physical, social, and psychological demands of aging with polio. A shift in the medical/historical context of the post-vaccine era, from medicalization to disability rights and independent living, has re-defined disability as an interaction between the impairment and the social environment.7,8 The independent living and disability rights movement changed the guiding principle of rehabilitation from daily functional independence to self-direction in life decisions. Many rehabilitation clinicians with expertise in post-polio sequelae have shifted their expectations from an authoritarian role to a collaborative partnership with the patient.9,10

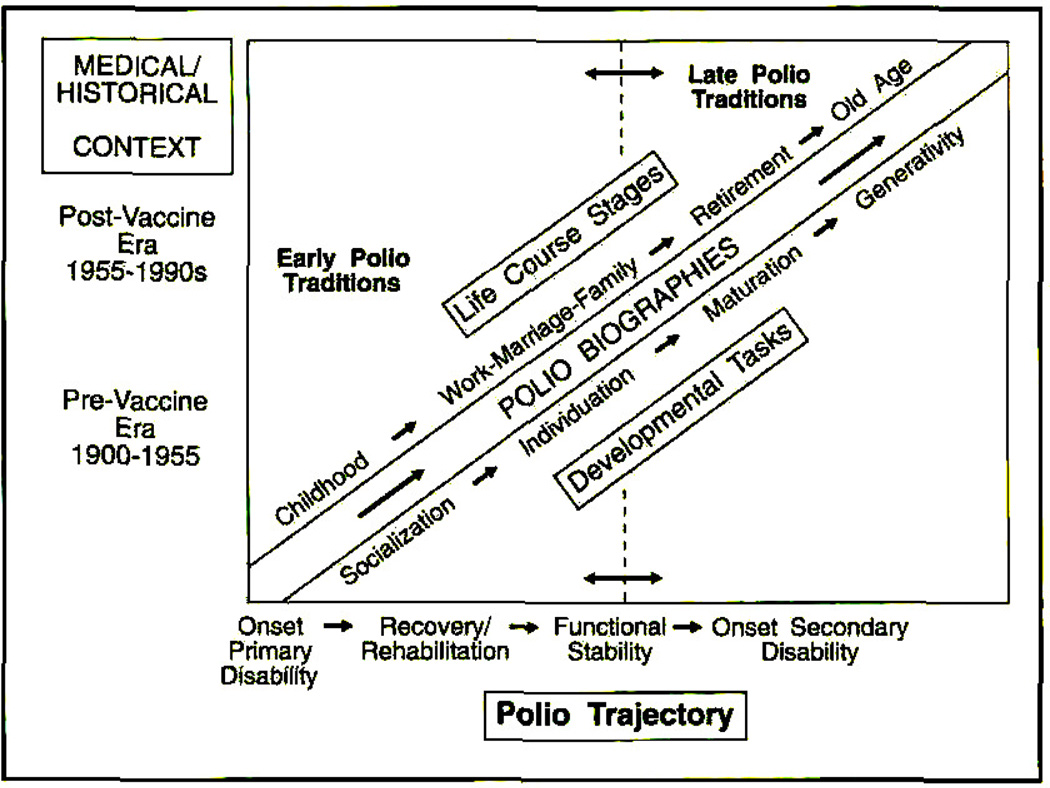

The concept of “polio biography” is introduced in Figure 2. Polio biography locates the individuals’ interpretation of post-polio sequelae within the context of their lifetime experience.11,12 Rather than isolating the onset of new functional losses as a single, disease-oriented episode, the concept of polio biography is used to convey the lifetime totality and significance to an individual’s sense of being a whole person with a distinctive life history.

Fig 2.

Cultural contexts of polio biographies.

The individual’s biography is influenced by their position in the life span and life course. Life span refers to the chronologic duration of biological existence, from birth to death. The life course is the culturally defined script of normatively expected stages and transitions for the socially defined person.13 Each stage in the normative life course (eg, childhood, work-marriage-family, retirement, old age) is accompanied by a set of psychosocial developmental tasks (eg, socialization, individuation, maturation, integration/generativity).14 The life course provides a broadly shared timetable for evaluating the “on-time-ness” or the “off-time-ness” of expectable events and social development, from childhood to retirement.15 For example, post-polio sequelae are described by some professionals and survivors as “early aging,” because the state of the biological body does not match their culturally defined stage of life.

Each of these concurrent cultural contexts—changing medical and sociopolitical environments, polio traditions, and life course developmental stages—form the life experience and sense of personal identity of polio survivors as they move into mid and late life with new functional deficits. Life course issues frame the parameters of polio biographies. Concerns for continuity with elements of the personal past are significant for polio survivors as they confront secondary disabilities, and are similar to the concerns of persons involved in other kinds of life course changes, such as bereavement.16,17 Polio traditions remain an enduring force in the lives of polio survivors and often are highly personalized and well-integrated within personal identities. Like ethnic traditions, polio traditions are not reversed in a clean sweep when individuals respond to new challenges, such as post-polio sequelae.18 Late polio traditions continue to evolve and contribute to a new repertoire of cultural resources for some polio survivors.2

Life Course

Polio survivors interpret new functional losses and modified patterns of daily living in the context of their life course stage and developmental tasks (Fig 2).

Disrupted life course

A recurring major theme was the perception that the onset of secondary disabilities separated polio survivors from their peer group and from leading the kind of life they expected to be living at that phase in life. Three case studies illustrate the theme of disrupted life course. Mr Radnor describes perceiving himself as living outside the boundaries of his normative life course stage:

Sam Radnor is a 54-year-otd early retiree, married with five children. He had polio at age 22, was initially paralyzed in his right arm and leg, and recovered with a slight limp. Two years prior to coming to the post-polio clinic. Mr Radnor began to use crutches and a wheelchair. These interventions enabled him to continue working, but he decided to retire early due to severe fatigue. He had built a business from the ground up, and was sad to have to give it up when it had started to be ‘more fun.’

The rehabilitation team advised him to rest more, pace his activities, modify his exercise routine, purchase lightweight leg braces and a lightweight wheelchair, and join the local post-polio support group to help manage the multiple losses. During the team wrap-up conference, he reflected, ‘when I visited my mother in the nursing home last year, I saw people in their 70s and 80s moving around the way my body moves now. The nursing home is a mirror I didn’t think I’d be looking in for another 30 years. And here I am retiring at 54. Is the nursing home the next stop1?’

Yet Mr Radnor found it hard to identity with other polio survivors, Even after 6 months, ‘the polio bunch was not for me. I couldn’t relate with them. I would have preferred a group of newly handicapped people who were my own age: new amputees, new strokes. I have more in common with a newly blinded person my own age than another polio.’

Mr Radnor’s life was sharply disrupted by the onset of secondary disabilities. A vigorous businessman, he never expected to retire in his 50s. He had not defined himself as disabled, even though his limp limited his ability to participate in some activities, such as sports. Mr Radnor’s attention was not focused on the life he could lead, but on the life he had to stop living. He was frightened by the image of nursing homes in his near future. He identified more with his age-mates who were also learning to manage new disabilities. Polio survivors of varying age levels did not meet his need for support; he wanted to be with people like himself.

In contrast, Ms Bender had made the transition to retirement in her mid 60s before the onset of secondary disabilities. However, she found herself at age 87 experiencing similar frustrations. She, too, experienced her biography as “off-time” because the onset of new symptoms changed what she expected herself to be doing during retirement. For her, a thematic issue concerned barriers to fulfilling late life developmental tasks of generativity:

Rebecca Bender, an older single woman, taught school all of her life and actively participated in her extended family as the designated ‘family matriarch.’ Ms Bender did not perceive herself to be handicapped by her lifelong leg weakness that required her to use braces and crutches, but has felt terribly handicapped by the onset of new. generalized weakness and fatigue.

She said, ‘if I weren’t crippled, I know that at this age I would do volunteer work. I would go and help people that are less able than I am. And, you know, that bothers me quite a bit because I can’t. I feel that I’m useless right now. That’s the exact feeling I get, because every bit of strength I have I need to save for myself, to take care of myself as the day goes on.’

Clearly, the interplay between life course, aging, adult development, and biographical concerns emerges here. “Feeling useless” reveals several factors: the immense time and energy demands of self-care coupled with declining energy produces an experience Ms Bender interprets as unacceptably narcissistic at the expense of engagement with other people and activities. Her diminished self-esteem reflects the force of American cultural ideals of independence and autonomy into late life. For Ms Bender, the time and energy required to be independent and autonomous challenge her ability to fulfill late life development tasks of generativity and avoiding stagnation and narcissistic self-involvement.14,19

Mid-life role requirements are multidimensional, including obligations to be economically productive at home and/or in the workplace. If a person has growing children, the onset of secondary disabilities can change family role dynamics. Henry Stern, a successful lawyer and father in his early 40s, had used a brace and crutches since he was a child, and recently started to use a wheelchair for long distances. Although he was dramatically less tired, he reflected longingly about the implications of his decision to use a wheelchair:

Yes, there are a lot of losses. And some gains; you can go faster than most people and carry more stuff. Thank goodness for the new streamlined chairs. I remember the old clunkers all too well. If there is such a thing as a nice-looking wheelchair, then mine is, but I’m still really ambivalent. I do what I’m supposed to do because I’ve been to the clinic and I know what’s wrong with me and what has to be done. If I kept on walking I eventually wouldn’t be able to get up anymore at all. The option that exists now, to get out of the chair, wouldn’t even be there. But there are many times when I wonder what am I saving it for. Why don’t I keep walking until I can’t walk at all? If I followed that route, I wouldn’t have to defend my cases in court from a wheelchair and feel diminished in stature. I could go on a hike with my son tomorrow. It’s supposed to be a crisp clear day in the Shenandoahs. Instead, I’ll be at home, supervising my son as he rakes the leaves in the backyard.

Changing family perceptions in mid-life

Family, friends, neighbors, and co-workers respond to the unexpected onset of functional losses in a variety of ways. Mrs Stafford, a 45-year-old mother of three young children, had to face changes in how her children perceive her:

Gina Stafford has never used mobility devices, but has weakened muscles in her stomach and back and has walked with a weak left leg since her childhood polio. Two years before coming into the post-polio clinic, she started to notice difficulty rising from chairs, and using stairs, and fatigue when she walked longer than a few blocks.

When she found herself being too tired to cook dinner on most evenings, she hired a housekeeper and went to a post-polio clinic to find out ‘if she was crazy or if something real was happening.’

After learning about how post-polio sequelae were affecting her body, Mrs Stafford changed some of her daily activities. She rested each afternoon, swam twice each week, and ordered a handicapped parking permit. If these changes were ‘not enough, then I’ll think about spending money on a stair glide.’ She took naps in the car while her children competed in swim meets. But she found her previously talkative 13-year-old daughter growing silent. Her daughter confided that she was embarrassed to be seen by her friends in a car with ‘those license plates,’ ‘Why can’t you be like other moms? Why are you different?’ she asked over and over again.

Mrs Stafford discovered an unexpected focus to her daughter’s adolescence—the visibility of her heretofore invisible disability. Aware that her daughter’s need for her to “be like other moms” was a normal part of adolescence, a time when the need to belong gains new intensity, it also increased her own anxiety. How would her children perceive her if she needed braces or a wheelchair some day?

Loss of lifelong social resources in late life

In late life, social networks decrease due to retirement and death. The loss of lifetime dependable family, friends, and neighbors undercuts self-care strategies and resources. Mrs Tate, an 80-year-old widow, retired office worker, and mother, speaks of the impact of widowhood on secondary disability management:

Barbara Tate had always relied on her husband to custom fit the shoes she had specially made by a local cobbler. As careful as the cobbler worked, he could never get the fit exactly right. Her husband took pleasure in whisking her shoes into his workshop and adapting them to fit her feet and the way she walked. Since her husband died 10 years ago, Mrs Tate has worn 10 year old shoes. She says, ‘Last year I had some beautiful shoes made. But I can’t wear them. They knock—and when I go to try to walk in them I fall down. They’re just not right. For years, when my husband was alive, I would take my shoes to him and say, ‘these shoes aren’t right, John’ and he’d take them down to the basement and fix them. He understood my feet.’

With the death of her husband, Mrs Tate lost both a beloved life partner and a valuable disability ally who helped her maintain physical comfort and functional capacity.

New losses and altered social integration patterns

Along with social relationships, the social setting in which lives are embedded is significant to the way new losses are interpreted. Ms Sherman, a retired 87-year-old, describes how using a wheelchair is redefined in a geriatric center setting where wheelchair users are generally cognitively impaired and need help dressing, eating, and managing daily activities.

Bemice Sherman uses a wheelchair to travel the long distances around her apartment building that is part of a geriatric center. In her apartment, she uses braces and crutches to negotiate short distances. In the residential setting, Ms Sherman endures a lot of verbal complaints from other residents because she uses a wheelchair to manage the fatigue of walking distances and waiting for the slow elevators. Residents expect that any wheelchair user should live in the nursing home section, not in the independent apartments. Regulations require that Ms Sherman be able to walk in and out of the dining hall without her wheelchair to stay in the independent apartments.

Other residents say the sight of Ms Sherman in a wheelchair upsets them. ‘When I come to the dining room they tell me ‘you can’t come in,’ they don’t want a wheelchair around them. So I go early or late. People feel a wheelchair is the last thing. They can walk with a walker, a cane, or be blind. But when you’re with a wheelchair, this is it, you don’t belong here. People resent h and they don’t make any bones about it, believe me they don’t.’ When asked why the residents see her ‘like everyone else’ and not a polio survivor, she said: ‘They think, ‘look at that! She has a wheelchair and she still takes care of herself.’ Usually people with wheelchairs have a companion with them. And I don’t have anyone taking care of me. They don’t think about why I use a wheelchair.’

Using a wheelchair in this setting denotes a specific set of social meanings. To maintain her good neighbor relations and sense of self-esteem, Ms Sherman has learned to continually assert the uniqueness of her use of the wheelchair in the perspective of her lifetime experience with polio. However, the official rules and informal peer pressure work to isolate her further.

Other polio survivors interpret their new limitations as a way to connect with others of their own age group who are also experiencing disabilities.5 For some, it is a connection to a peer group that they have never known, because of a perceived difference from others. Mrs McColl learned that a strategy to manage her new disabilities gave her an invitation to a new group of women with other disabilities:

Kate McColl is a 79-year-old married, retired social worker who had walked with a limp since she had polio as a child. She came to the clinic to learn how to manage new leg pain, weakness, and more frequent falls. The rehabilitation team advised her to use a brace and cane and to swim as often as she could. Frightened by the falling and increased weakness, Mrs McColl was relieved by using a brace and cane, and began to swim several times each week in a neighborhood heated pool. She went at the same time several mornings each week and began to meet other older women who had arthritis and were also ‘Swimming for pain.’ Mrs. McColl talked about the camaraderie she found among ‘the swimmers,’ and that the other women looked to her with respect based on her lifetime experience with disability.

Use of “aging” as explanation for new losses

A trend observed among the older (age 60 and over) informants was that they depicted the nature and personal implications of their new losses by a set of references to folk beliefs about aging. This was possibly reinforced during encounters with health professionals who told them that the symptoms they reported, later diagnosed by specialists as related to polio, were “just the usual thing as you get older.”

Social consequences vary with the attribution of secondary disabilities as being “normal aging-related” or “polio-related.” The mid-life survivors described experiencing a sense of increasing difference and marginalization following the onset of their new losses, as illustrated in the case of Mr Radnor. The older informants who interpreted the new symptoms as “normal aging-related” identified with age peers and in some cases gained an enhanced sense of prestige from serving as an experienced disability elder. For some, the “normal aging-related” interpretation provides a source of solidarity and shared identity, as is the case of Mrs Rubin, a 67-year-old married woman:

When I was young I felt very, very, very different. I remember when I was in high school I wouldn’t walk in front of the other kids. I would go hide. And now I feel much more normal because I’m older and it’s much more acceptable to be handicapped.

By metaphorically describing the polio-related disabilities as “normal aging” changes of the body and decreased energy levels, Mrs Rubin bridges the social gap between the disabled and the nondisabled. Such individuals assert a similarity with others in the normative life course stage of old age, and they assert a merging with their same age peers after years of visible difference. They note that their gait—slower, less smooth, and more deliberate—is no longer a sign of difference. Or their handwriting, always a little shaky, now matches that of their elderly peers who also write “in a spidery way.”

Older informants report feeling more fortunate than their same-age peers who face diminished functional capacity for the first time. A 76-year-old single woman pridefully remarked, “I’ve had plenty of time to learn all that stuff; and to accept asking for help if I need it to do what I want; adapting just becomes a part of life after years and years.” That is, her lifelong expertise at managing functional impairments gave her both instrumental skills for daily functioning and self-management skills, such as prioritizing and pacing. Further, some older subjects described having established and learned to maintain informal support networks, and have more knowledge of the imperfect service sector compared with their non-impaired peers.

Polio Traditions

In addition to life course and developmental challenges, polio survivors also interpret new disabling symptoms in the context of their early and later life experiences with polio rehabilitation practices and broad social expectations (Fig 1).

Early and Late Polio Traditions

A specific set of values and beliefs developed in the context of the polio epidemics.20 The early polio traditions that emerged were refined in rehabilitation settings and later reinforced in the family and other social institutions.21 These settings continue to be the context of revitalized polio traditions which continue to change and develop in response to the new demands of secondary disabilities. Polio traditions are a condensation of some core American values learned during the rehabilitation and recovery phase and reinforced in the broad context of American values, expectations, norms, and ideals.

With the onset of new functional losses, rehabilitation practitioners radically changed the polio prescription from “use it or lose it,” to “conserve it or lose it.” Persons who are evaluated in post-polio clinics are regularly advised to “slow down, stop trying to do so much, don’t try to do everything.” Many experience the new polio prescription as a request to “stop living” because it was the only way of life they knew. They had used the early polio prescription and the work ethic to achieve their life goals; they established families and careers, owned businesses, and assumed leadership roles in their communities.

The work ethic

The person’s capacity to disregard obvious physical impairments and not integrate them into personal identities has much to do with psychological factors, but is also influenced by the polio tradition of using the work ethic to minimize physical limitations. Persons who used the work ethic in this way stated that, although they could not do certain activities, they did not consider themselves handicapped by their disabilities.

The work ethic had special importance to polio survivors. It was one passage to normalization. The practice of pushing oneself beyond one’s limits to achieve goals and “pass” into the mainstream allowed many persons to not perceive of themselves as handicapped, but. simply unable to perform certain functions. The work ethic allowed them to use self-sufficiency, achievement, and productivity as ways to cope with feelings of difference, social rejection, and inequality.1,22 For some, a tradition developed of using an intensified version of the work ethic to cope with the loss of physical capacities. They learned to minimize and “overcome” their physical limitations by persistent striving to be productive and active at work, at home, and in their communities. The practice of productivity countered the stereotypical image of persons with disabilities as dependent, inactive, and unproductive held by themselves and others. In some cases, the highly productive persons were severely disabled:

Bill Light, a 42-year-old lawyer, drives himself hard to maintain a private practice and teach at a university. His wife, who works with him as a paralegal, says, ‘Bill has not felt disabled a day in his life.’ Mr Light became paraplegic at age 4. At maximum recovery, he could push his wheelchair for short distances, but needed someone to push him for a long distance. He could feed himself and required help with bathing, dressing, and most transfers. For 3 years prior to visiting the polio clinic, Mr Light experienced severe fatigue, shortness of breath, muscle pain and weakness, and difficulty sleeping. He said. ‘I feel disabled for the very first time in my life.’

Mr Light was advised to consult with a pulmonologist and it was discovered that his carbon dioxide was significantly elevated. He began to use a chest respirator at night which eliminated fatigue completely: he stopped tailing asleep while driving and began to sleep well throughout the night. Mr Light was elated: ‘I feel much better, have more energy, and much improved endurance. I have been born again.’ His wife added, ‘Bill has been an such a downhill slide over the past few years, I didn’t think he would live very long. It’s like I’ve got my old husband back.’

Three years after his initial clinic visit. Mr Light reports, ‘I know that I’m alive today because of my evaluation at the post-polio clinic and help from a pulmonologist.’ He continues to work at his busy law practice and is now a circuit court judge. When asked if he rests during the day, ‘No, I don’t take naps and I don’t pace my activities, either. I’d like to take a nap but I don’t have the time.’ Mr Light has returned to pushing himself and reports that he often doesn’t have time to eat breakfast until 3:00 in the afternoon.

Mr Light returned to thinking about himself as having had polio in the past, and not being disabled. He used some of the early messages learned during polio rehabilitation and recovery to move into the social mainstream. The early polio prescription was to establish goals, work hard, and push oneself beyond perceived limits. This message “fit” well within the highly valued American work ethic. The work ethic requires the individual to take responsibility for overcoming personal adversities by working hard in the pursuit of goals. Because of the capacity of polio-damaged nerves to recover function with time and rigorous exercise, some persons who had polio found that if they practiced the work ethic in terms of their recovery, their bodies responded favorably. Clinicians taught patients to work their muscles hard to minimize pain and discomfort in hopes of regaining lost functional capacities for the long term. The message was simply “use it or lose it. ”23 Survivors report that physical therapists told them to “push yourself until it hurts and then push some more.” Most of them complied with the polio rehabilitation regimen and found they gained often a significant degree of function.

The moderate or severely disabled person, such as Mr Light, used the work ethic to “pass” into the mainstream. In our society, persons who practice the work ethic and achieve some degree of success generally may receive social acceptance and respect, even an extra measure of prestige, since those who are productive and disabled are seen as overcoming adversity. The admiration, however, is tinged with devaluation because implicitly, people with disabilities are not expected to achieve success unless they are remarkable.

“Forget your polio.”

Another aspect of the early rehabilitation regimen encouraged polio patients to forget their polio and put the past behind them. The psychological process of denial and minimization of loss, pain, and discomfort has psychological benefits and possibly survival value, especially during the first years of being disabled.24 However, the advice to forget stayed in place beyond the first few months when benefits were highest. Polio survivors were encouraged to try to do everything that people without disabilities did. Their special needs went unrecognized or in some cases were considered shameful. They were expected to achieve in all spheres of life, in spite of their disabilities. They learned how to compensate for what they could not do. The implications were double-edged: the behaviors inspired by these messages were adaptive for regaining muscle strength and for participating in the mainstream, but they negated the psychological realities of physical loss, vulnerability, and long-term living with a disability. This negation had the cost of distancing and removing persons from an important aspect of their own lives.

Since survivors are at risk to lose the very functions they worked hard to re-gain during their rehabilitation and recovery period, when function is lost some describe the experience as “like having polio again.” Frick25 describes polio survivors who view themselves as having a “second disability” when they develop new disabling symptoms. Scheer1 found two subgroups of polio survivors in a sample of clinic-based and support group populations: persons for whom post-polio sequelae are experienced as a “first disability”; and persons for whom post-polio sequelae represent a “second disability.” Prior to the onset of new functional impairments, the “first disability” subgroup did not identify themselves as handicapped by their primary polio disability, regardless of the extent of paralytic involvement or deformities. In contrast, the “second disability” subgroup had viewed themselves as being handicapped by their primary polio disability before the onset of their new limitations, and currently regard themselves as being “twice disabled.”

In the context of new functional losses and the revised polio rehabilitation prescription, “conserve it or lose it,” “forgetting your polio” is no longer possible. Assistive devices are often recommended. For some, the stigma of using mobility aids, public markers of disability, curtails the use of lifelong minimization and denial as coping strategies.

Suzanne Pane is a 49-year-old homemaker with two children in college. She had polio at age 9, followed by surgeries during adolescence to stabilize her ankle. Mrs Pane always walked with a limp and sway motion, and had never used ossistive devices. She says. ‘I have always felt different from other people. Ever since I was a child. People look and stare at the way I walk.’ For the past 5 years, Mrs Pane has experienced whole body fatigue, muscle weakness, and pain and came to the post-polio clinic to ‘get a diagnosis.’ The rehabilitation tearn advised Mrs Pane to pace her daily activities and rest before she gets tired, use lumbar pillows to support her back, and to use a cane.

During the next year, Mrs Pane began to rest during the day and used pillows for driving and sitting. The cane was another matter. She said ‘I knew I needed a cane even before I came to the clinic because I felt much better when I could use a shopping cart at the grocery store. With a cane, ‘my walking looks better and smoother,’ but she doubts she will use a cane much in public. She says, ‘I know what it’s like when everywhere you go people stare and stare and stare. I hate that.’ Instead, Mrs Pane chose to limit her activities so that she is at home much of the time.

Three years later, Mrs Pane continues to be more homebound than she would like, but now carries the cane with her in the car to use for short walks in the woods with her husband. Her son plays college soccer and she uses a portable chair to see him play because ‘the chair doesn’t have ‘cane’ written all over it.’

Mrs Pane measures her success in terms of her ability to hide her physical limitations. This has led to increasing social isolation for an active woman at mid life. Rehabilitation success is traditionally measured in terms of gains in physical functional performance. Although recognized and highly valued by patients, family, and rehabilitation professionals, functional gains as defined by rehabilitation professionals are not always validated in the general community.21 Mrs Pane could be more autonomous and mobile with a cane, but the community stigmatizes those who appear visibly impaired. Becker and Kaufman26 discussed the difficulties stroke rehabilitation patients face from the clash between incremental successes recognized by clinicians and families, and the wider community which continues to label the patient in terms of impairment and lost function.

New polio pride

In the mid 1980s, self-help oriented post-polio support groups developed, many of which worked in partnership with a local post-polio clinic.27 They communicated with each other by networking through the International Polio Network’s directory, quarterly newsletter, and biannual national conferences. Survivors organized support groups in response to their frustration with health care professionals unfamiliar with the cause of their new symptoms, their uncertainty about future function, and the disruption in work, home living, and social relationships caused by needed lifestyle modifications.28

A shared polio pride surfaced in many support groups which was related to a new respect fostered by meeting other polio survivors with similar health and well-being issues. They therapeutically re-experienced their bouts with acute polio and earlier polio-related life experiences, such as physical therapy regimens, authoritarian physicians, using braces or a wheelchair in school, dating, and working hard to succeed at school, work, and home. They reclaimed their past together and felt affirmed about living productive lives “in spite of their disabilities.” The new polio pride is a source of group solidarity, a shared identity with other persons confronting the challenge of finding purpose and meaning in the face of now being able to do less.

Among themselves, they labelled their mutual achievement orientation as caused by “Type P” behavior and the “polio personality,” concepts developed by Bruno and Frick29 to describe common personality traits, modeled after the “Type A” personality associated with heart disease. Persons characterized themselves as having a polio personality, sharing traits that enabled them to “pass” into the mainstream, such as high levels of achievement at work and in the community and joy in living life fully. As stated in newsletters and in support group meetings, some survivors describe pride at being “overachievers” or “super-achievers,” and perceive their need to achieve as an unquestioned response to the societal and environmental barriers faced by people who are different in our society. At one meeting, the commonalities between contemporary “superwomen” who work, raise children, and take care of sick parents and polio lifetime “overachievers” who push themselves to their physical limits each day were discussed with humor and compassion.

However, self-labelling has a double edge. By labelling themselves as “overachievers,” instead of high achievers, they may at the same time conclude that, along with much of society-at-large, they did not expect themselves to achieve much at all. Inadvertently, they may perpetuate the notion that persons with disabilities are not expected to achieve, and if they do, it is a remarkable and super-human act. Ironically, concepts that undervalue people with disabilities, such as “cripple” or “wheelchair-bound,” or concepts that overvalue them, such as “overachiever” or “superachiever” both function to separate disabled persons from others and socially categorize them as “different.” The concept of a polio personality is a value-laden symbol used by some survivors to explain the source of their current polio-related health problems. They perceive themselves as “living too hard,” when in fact, no one anticipated the long-term physical consequences of their behavior, and in many cases they were struggling to meet normal life course expectations met by their non-disabled peers.

The concept of a polio personality is an important personal symbol for many polio survivors. It affirms and revitalizes the shared early and later polio experiences and creates a sense of shared identify as they learn to live with new disabling symptoms. For some, it is a resource for psychosocial life reorganization.18 For others, it is a banner of pride, a way for survivors to reclaim aspects of their own personal histories and to counter impulses to forget and put polio behind.

Clinical Implications

Anthropologists and social gerontologists have found that across the lifespan, effective functioning and well-being is fostered by a sense of personal continuity, a reflection of self that is a constant, despite corrosive physical, social, and psychological losses.17,30–32 Based on this finding, the polio tradition of working hard to meet goals and surmount adversity can be translated to the task of life reorganization16–18 demanded by the onset of secondary disabilities.

We have observed that persistence and flexibility, important aspects of the work ethic and polio tradition, can be applied to helping patients achieve the new rehabilitation goals. Patients can learn that the tasks of accommodation to secondary disabilities require a different kind of hard work. For example, patients need to be taught to rest daily. Setting reduced daily activity priorities and sticking to them can be redefined as “work,” which polio survivors can be encouraged by clinicians to value. The qualities learned and valued by polio survivors in the course of adaptation to their primary disabilities—determination, steadfastness, consistency, and problem solving—are essential tools for life-building which can be reinforced and validated in clinical settings, and applied to their management of new secondary disabilities.

Rehabilitation clinicians need training in techniques to facilitate their patients’ participation in investigating the personal significance of new functional losses in relation to meaning and patterns in their own lives. Clinicians must recognize each client’s perception of his or her biography, and the influence of cultural as well as personal values and ideals. Since psychosocial stress seems to exacerbate symptoms,22 it is important to understand what patients perceive as distressing. An important finding of our work is that survivors do not just focus concern on their new impairments—the medically defined condition—but on the implications for the pursuit of present and future goals and the potential for participation in valued social relationships and interactions. A second finding is the importance of the life course perspective. Clinicians should be sensitized to the importance of the life stage developmental tasks challenging their patients as they interpret the personal meanings of new, unexpected secondary disabilities.

Patients also need assistance in clarifying their own insights into the ways in which their past experience can be used in their present context.3,18,22,33 Clinicians can help patients focus on the specialized capacities many polio survivors have refined over the years in the areas of problem solving, flexibility, and redefining the wider cultural ideals and values for their personal use. Polio traditions can function as both a source of distress when facing secondary functional losses, or as a valuable resource that trained health professionals can help survivors use. Polio traditions were learned and cannot be changed in a wholesale fashion, but instead can be modified to meet the demands of new functional losses. Clinicians may be able to use polio traditions as a resource, rather than as a barrier to change, to improve compliance with treatment recommendations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the polio survivors who gave their time to teach us about lifetime polio experiences; names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect privacy. We also thank Ruth Brannon. Richard Bruno. Gerben DeJong, Lauro Halstead. and Vijay Jethanandani for collaboration with analysis and manuscript development.

Research funds for Scheer were provided by the National Institute on Aging (Postdoctoral Research and Training Grants #2F32AGO5447-02 and #2F32AGO5447-03) and the National Rehabilitation Hospital Research Center. Grants to Luborsky from the National Institute on Aging (#RO1-AGO9065) and the National Institute on Mental Health (#2PO1AGO3934) supported his research and analysis, and are also gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scheer J. Survivorship: the American post-polio experience; Presented at the American Anthropological Association Meeting; Washington, DC. 1989. Dec, [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheer J. Is there a polio culture?; Presented at the Society for Disability Study Meeting; Washington, DC. 1990. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheer J. Voices of struggle and rebirth: persons learning to manage the late effects of polio; Presented at the First Norwegian National Polio Conference; Oslo, Norway. 1991. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luborsky M. Cultural, identity, and lifetime factors in adaptive device appraisals by lifetime users facing new losses. In: Itey S, Kige O, editors. Studies in Disabilities. OR: Willamette University; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luborsky M. Adaptive device appraisals and use among lifetime disabled adults; Presented at Society for Disability Studies Meeting; Washington, DC. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhodes LA. Studying biomedicine as a cultural system. In: Johnson TM, Sargent CF, editors. Medical Anthropology: Contemporary Theory and Method. New York, NY: Praeger Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeJong G. Independent living: from social movement to analytic paradigm. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1979;50:435–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scotch R. From Good Will to Civil Rights: Transforming Federal Disability Policy. Philadelphia. Pa: Temple University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young G. Occupational therapy and the post-polio syndrome. J Occup Therapy. 1989;43:97–103. doi: 10.5014/ajot.43.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith L. Current issues in neurological rehabilitation. In: Umphred D, editor. Neurological Rehabilitation. St. Louis. Mo: C.V. Mosby; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohler B. Personal narrative and life course. In: Baltes P, Brim O, editors. Life-span Development and Behavior. Vol. 4. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neugarten B, Hagestad G. Age and the life course. In: Binstock R, Shanas E, editors. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fry C. Culture and the life course. In: Rubinstein R, editor. Anthropology and Aging: A Comprehensive Review. Boston, Mass: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erikson E, Erikson J, Kivnik H. Vital Involvement in Old Age. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seltzer M, Troll L. Expected life history. American Behavioral Science. 1985;29:745–764. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luborsky M, Rubinstein R. Ethnic differences in elderly widowers’ reactions to bereavement. In: Sokolovsky J, editor. Cultural Dimensions of Aging: Worldwide Perspectives. Brooklyn, NY: Bergin and Garvey; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myerhoff B. Number Our Days. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luborsky M, Rubinstein R. Ethnicity and lifetimes: self-concepts and situational contexts of ethnic identity in late life. In: Gelfand D, Barresi C, editors. Ethnic Dimensions of Aging. New York, NY: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotre L. Outliving the Self: Generativity and the Interpretation of Lives. Baltimore, Md: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher HG. FDR's Splendid Deception. New York. NY: Dodd, Mead; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis F. Passage Through Crisis: Polio Victims and Families. New York, NY: Bobbs-Merrill; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruno RL, Frick NM. The psychology of polio as prelude to post-polio sequelae: behavior modification and psychotherapy. Orthopedics. 1991;14:1185–1193. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19911101-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halstead LS. Late complications of poliomyelitis. In: Goodgold J, editor. Rehabilitation Medicine. St Louis, Mo: C.V. Mosby; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treischmann RB. Aging with a Disability. New York, NY: Demos Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frick NM. Post-polio sequelae and the psychology of second disability. Orthopedics. 1985;8:851–856. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19850701-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker G, Kaufman S. Old age, rehabilitation and research. J Gerontol. 1990;28:459–468. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laurie G. The role of networking and support groups. In: Munsat TL, editor. Post Polio Syndrome. Boston, Mass: Butterworth-Neinemann; l991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith DW. Community resources: a personal perspective. In: Munsat TL, editor. Post Polio Syndrome. Boston, Mass: Butterwoth-Neinemann; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruno RL, Frick NM. Stress and “type A” behavior as precipitants of post-polio sequelae. In: Halstead LS, Wiechers DO, editors. Research and Clinical Aspects of the Late Effects of Poliomyelitis. White Plains, NY: March of Dimes; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antonovsky A. Health, Stress, and Coping. London: Jossey-Bass; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atehley R. A continuity theory of normal aging. Gerontalogist. 1989;29:183–190. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiske M, Chiriboga D. Change and Continuity in Adult Lift. London: Jossey-Bass; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peach PE, Olejnik S. Effect of treatment and noncompliance on post-polio sequelae. Orthopedics. 1991;14:1199–1203. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19911101-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]