Abstract

This longitudinal study employed the Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised in assessing temperamental differences between infants at 6 months (n = 114 US, 184 Dutch) and 12 months (n = 92 US, 172 Dutch) from the United States of America and The Netherlands. Main effects indicated that Dutch infants were rated higher on the Orienting/Regulatory Capacity factor and fine-grained dimensions of Smiling and Laughter, Falling Reactivity, Cuddliness, Low-Intensity Pleasure, and Soothability; whereas US infants received higher ratings on the Negative Affectivity factor and on dimensions of Activity Level, Vocal Reactivity, Fear, Frustration, and Sadness. Cultural differences for Orienting/Regulatory Capacity were more pronounced in early infancy, cultural differences for Fear were stronger in late infancy, and US infants demonstrated higher Duration of Orienting at 12 months only. Culture also appeared to impact the pace of consolidation of temperamental characteristics, with greater stability exhibited by US than Dutch infants in Smiling and Laughter and Vocal Reactivity.

Temperament refers to early-emerging, relatively stable and biologically driven individual differences in reactivity and regulation, with reactivity referring to arousability to stimuli and regulation to processes that enhance or inhibit this reactivity (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Cross-cultural investigations of temperament are valuable for at least two reasons. First, a cross-cultural approach provides an important tool for understanding the origins of individual differences in development. Differences between cultures in terms of environmental and genetic factors influencing temperament are likely to be pronounced, reflected in greater variability in the outcomes of interest. Second, documenting differences in temperament between cultures is informative regarding the application of findings obtained in a given culture to developmental phenomena in others. This research is likely to play a critical role in increasing our understanding of factors that may limit generalizability, and the recognition of environment-temperament interactions as processes leading to adaptive or maladaptive patterns of behavior. With some exceptions, prior studies of cross-cultural differences in infant temperament have largely considered distinctions between Western and non-Western societies (see Chen, Yang, & Fu, 2012). It is important to recognize, however, that substantial cultural and genetic differences exist among Western nations, and these variations may be associated with distinctive patterns of individual differences in even the youngest citizens. The current investigation contributes to knowledge in this realm through a cross-cultural investigation of temperamental differences between infants, assessed at 6 and 12 months, raised in The Netherlands and United States.

The “developmental niche” (Super et al., 1996) provides a theoretical framework for cultural impact on child development, including temperament. In this model, the child’s environment is conceptualized in terms of the settings inhabited by the child, customs regarding care, and parental belief systems that shape parents’ attitudes about development and behavioral responses to children, differentially structuring children’s daily lives. These parenting practices, in turn, likely shape children’s temperament as well as caregivers’ evaluations of their children’s temperaments. Harkness and Super (2006; Super et al., 1996) have identified salient differences in the developmental niches of The Netherlands and US, evident in themes embedded in parents’ accounts of their offspring. In free descriptions of their children, Dutch parents frequently comment on their children’s agreeableness and attention span. In contrast, US parents more often describe their progeny as intelligent or cognitively advanced. Regarding parenting beliefs and behavior, US parents often emphasize the importance of stimulation, seeking a wide variety of experiences for their children to promote cultural ideals regarding independence. In contrast, parents in Holland are more likely to incorporate children into daily activities in familiar settings, placing strong value on the importance of rest and regularity. Harkness and Super (2006) suggest that differences between these cultures in terms of sleep promotion and stimulation may lead US infants to be more active and aroused than their Dutch counterparts. Given the relation between sleep and emotion regulation (e.g., Sadeh, Gruber, &Raviv, 2002), it can be hypothesized that Dutch infants may exhibit lower levels of negative affect, and more rapid soothing upon distress, than infants raised in the US.

In addition to parental belief systems and related environmental structuring, between-culture differences in temperament may also be influenced by the relative proportion of individuals in a population whose genetic profile includes alleles associated with patterns of behavioral reactivity and regulation. The short allele of the serotonin transporter gene 5-HTTLPR has been linked to high levels of negative emotions and is slightly more prevalent in US samples than those from The Netherlands (Chiao and Blizinsky, 2009). The high expression allele of the MAOA-uVNTR gene, which has been associated with greater social sensitivity, is more common in Dutch than US populations (Way & Lieberman, 2010). These findings suggest the possibility of greater demonstration of negative affect and lower levels of traits associated with positive social interaction in infants from the US, in comparison to those from The Netherlands.

To our knowledge, no prior study has directly explored temperamental differences between infants from the United States and The Netherlands using standardized questionnaires. The use of this type of instrument is beneficial, as it requires reporting on behaviors that may be less salient to certain parents, providing a more detailed perspective on children’s characteristics than unstructured interview formats, such as those used by Harkness and Super. In addition, parental bias, including culture-based bias, may be reduced when questions are framed in ways that do not require parents to make comparative judgments or general ratings. As such, the Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (IBQ-R; Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003) used in the current study may be particularly well-suited for cross-cultural investigations, as it includes more scales than other infant temperament questionnaires, and because items ask parents to rate the frequency of concrete behaviors in specific contexts.

Factor analyses of the 14 IBQ-R scales have repeatedly revealed three higher-order factors (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003; Montirosso, Cozzi, Putnam, Gartstein, & Borgatti, 2011): Surgency (SUR; comprising scales measuring Activity Level, Approach, Vocal Reactivity, High Intensity Pleasure, Smiling and Laughter, and Perceptual Sensitivity), Negative Affectivity (NEG; comprising Distress to Limitations, Fear, Sadness, and, loading negatively, Falling Reactivity), and Orienting/Regulatory Capacity (ORC; comprising Cuddliness, Duration of Orienting, Low Intensity Pleasure, and Soothability). These factors are conceptually similar to those which have emerged from investigations of adult personality (e.g., Digman, 1990). Like adult Extraversion, SUR indicates an approach-oriented or exuberant disposition and enjoyment of novel and intense activities. NEG, similar to adult Neuroticism, is marked by frequent and pronounced displays of negative emotions. ORC and adult Conscientiousness both involve capacities for extended attentional focus and enjoyment of low-intensity activities, and ORC during infancy has been shown to predict Effortful Control, including the ability to inhibit undesirable behavior, in later childhood (Putnam, Rothbart, & Gartstein, 2008). Whereas identification of cultural differences at the factor level are important in their own right, the fine-grained scales can elucidate differences that may be obscured at the factor level, including those found to differentially predict outcomes across cultures (Gartstein, Slobodskaya, Kirchhoff, & Putnam, 2013).

Prior cross-cultural research using the IBQ-R, or its predecessor, the IBQ, has compared US infants to those from China, Finland, Russia, Japan, Poland and Italy, finding infants from the US infants to be rated higher on aspects of SUR, and lower on aspects of NEG than infants from other countries (Gaias et al., 2012; Gartstein et al., 2006; Gartstein, Slobodskaya, Zylicz, Gosztyla, & Nakagawa, 2010; Montirosso et al., 2011). These trends, however, did not extend to all fine-grained dimensions, or all countries. For example, Gartstein et al. (2010) reported significant differences in SUR between infants from US, Russia, Japan, and Poland, but the differences between infants from the US and elsewhere were largely restricted to the subdimensions of Vocal reactivity and High-Intensity Pleasure, and Gaias et al. (2012) found Finnish infants to be higher than US infants in Smiling and Laughter, also reporting higher Fearfulness among US infants. Findings are particularly mixed regarding aspects of ORC, with US infants scoring higher than Italian infants on Low-Intensity pleasure while Italian infants scored higher on Cuddliness (Montirosso et al., 2011); and Finnish infants were rated as higher than US infants on Duration of Orienting (Gaias et al., 2012).

Although the temperament of Dutch and US infants has not been compared, findings regarding temperament in older children and personality in adults may be informative. In a study of older children assessed with the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire, Dutch children ranked lower on elements of SUR and NEG than their US counterparts (Majdandžić et al., 2009). In adults, both Allik and McCrae (2004) and Schmitt, Allik, McCrae, and Benet-Martinez (2007) revealed higher Neuroticism in US than Dutch samples, but findings regarding other traits were inconsistent: whereas Allik and McCrae (2004) found Americans to be somewhat more Extraverted and Open, but less Conscientious and Agreeable than their Dutch counterparts, Schmitt et al. (2007) reported higher Conscientiousness and Agreeableness among US adults, and negligible differences for Extraversion and Openness. Combined, these studies lead us to strongly expect higher scores in aspects of NEG and tentatively expect higher levels of SUR-related dimensions in US infants, but are equivocal regarding scales associated with ORC.

Based on prior research, gender and age moderation effects with respect to culture were explored. Montirosso et al. (2011) found Italian male babies to be higher than US males on Cuddliness, with smaller cultural differences for female infants. Regarding age, two issues were investigated. First, culture-by-age interactions were assessed to enhance understanding of how age might moderate the impact of culture on factor-level and fine-grained traits. Slobodskaya, Gartstein, Nakagawa, and Putnam (2013) found cultural effects between Russian, Japanese, and US infants on aspects of SUR and ORC were larger among younger infants, and we anticipated similar effects between US and Dutch babies.

Our longitudinal design also allowed us to investigate whether culture moderated levels of relative stability. That is, we ascertained whether correlations between temperament scores at 6 and 12 months were stronger in one culture than another. No prior studies have investigated the issue of differential stability, and predictions regarding these analyses are tentative. We anticipated, however, that prominence of a trait in parental ethnotheories may lead to earlier “consolidation” of these behavioral tendencies. For example, the salience of Surgency in US parents’ conceptualizations of infant characteristics may lead to enhanced awareness of behaviors associated with this aspect of temperament, as well as more organized parental reactions to such behaviors in the first year, leading to greater relative stability. In contrast, a less concerted focus on Surgency-related dimensions in The Netherlands may be associated with periodic shifts in infants’ displays of motoric, vocal and facial exuberance, such that stability of these behavioral profiles is less pronounced.

In sum, the current study examines cross-cultural differences in the parent-reported temperament of children assessed at 6 and 12 months of age. As described above, we hypothesize that US infants will receive higher ratings in elements of both SUR and NEG than Dutch infants, but we have no firm predictions regarding aspects of ORC. We additionally explore the possibility that some aspects of temperament may demonstrate differential levels of stability during infancy across the two countries, and tentatively anticipate greater stability in dimensions of Surgency in US infants.

Methods

Participants

The US sample was recruited in the Eastern Washington/Northern Idaho area and included healthy, typically developing children. Participants were recruited through birth announcements, as well as a primary prevention program offered to all families of newborns. Only families with healthy full-term infants were eligible to participate. An initial sample of 135 families was recruited, with 114 mothers completing the 6-month assessment, and 92 of these 114 providing IBQ-R data at 12 months. Families participating at both times were compared to those who dropped out of the study between 6 and 12 months in terms of maternal education, maternal age, infant sex, and all 6-month temperament scores. Continuing mothers were older, t (111) = 3.04, p< .01, and their infants scored lower on Activity Level, Duration of Orienting, Smiling and Laughter, Soothability, Vocal Reactivity, SUR and ORC, ts (111) from 2.17 to 4.43, ps< .05.

The Dutch sample was recruited through flyers that were spread among midwife practices in the cities of Nijmegen, Arnhem, and surrounding areas. Inclusion criteria were an uncomplicated, singleton, full-term pregnancy, no drug use, and no current physical or mental health problems. From an initial sample of 193 families, 184 mothers completed questionnaires at 6 months infant age, and 172 of these 184 participated at 12 months. In comparison to those who did not continue, infants in continuing families were rated as lower in High Intensity Pleasure, t (181) = 2.26, p< .05, and ORC, t (181) = 2.10, p< .05.

Analyses of maternal age and college attainment were conducted to estimate the comparability of the two samples. Mothers from The Netherlands were significantly older than those in the US sample (M = 32.39, sd = 3.94 for The Netherlands; M = 29.17, sd = 5.31 for US; t (237.44) = 6.12, p < .01). Comparisons of maternal education presented difficulties due to differing educational systems in the US and Netherlands. In each sample, a score was created so that 1=did not finish high school (US) or VMBO, MAVO OR HAVO degrees (NL); 2=completed high school, VMBO, MAVO OR HAVO degrees, but no participation in a professional or graduate program; 3=completed associates degree or less than 4 years of college education (US) or middle or higher professional education (NL); and 4=completed university degree. Mothers in the US sample scored higher on this scale (M = 3.22, sd = .61 for The Netherlands; M = 3.52, sd = .74 for US; t (261.33) = 4.06, p < .01). Because maternal age and education were also correlated with several aspects of temperament (available upon request from the corresponding author), maternal age and education were entered as covariates in the analyses of the effects of culture on average levels of temperament dimensions. Although inclusion of these covariates diminished the effect size for culture in several tests, the large majority remained significant.

Materials

Temperament was measured with the IBQ-R (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003) which contains 191 items for which parents rate the frequency of infants’ behaviors in commonly occurring situations, using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Scale scores are formed by averaging ratings for all relevant items, with high scores indicating that the infant exhibits higher levels of the trait. Cronbach’s alphas of the scales ranged from .71 to .93 in the US sample, and from .71 to .86 in the Dutch sample. Factor scores were created by averaging the scores of scales affiliated with SUR, NEG, and ORC.

Statistical Analyses

Our analyses are presented in two parts. First, to test whether culture is associated with differing average levels of temperament dimensions, 2 (culture) × 2(sex) × 2 (age) repeated measures ANOVAs, with maternal age and educational status included as covariates, were employed. Significant culture-by-age interactions were interpreted using follow-up tests (2 × 2 ANOVAs with covariates) of simple slopes that examined culture effects separately at 6 and 12 months. Second, to test whether stability of traits from 6 to 12 months differed between the two cultures, we calculated stability correlations in each culture, and then used Fisher’s Z tests to test whether the magnitude of these correlations differed significantly between the two cultures.

Results

Effects of Culture, Age and Gender

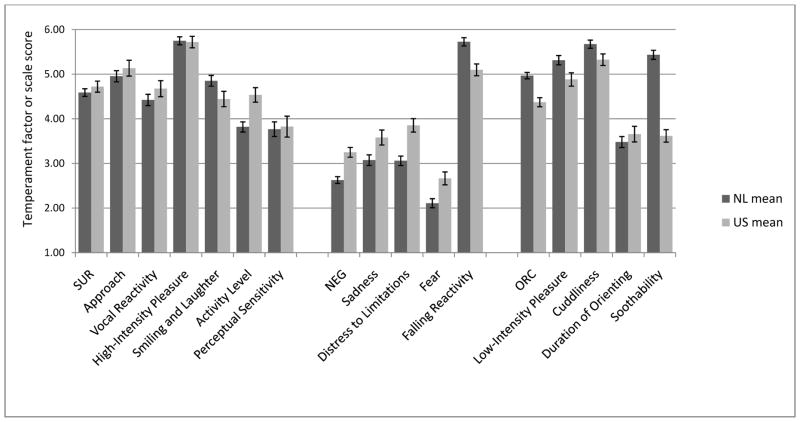

Means and standard deviations for all factor and dimension scores at 6 and 12 months in the two countries are shown in Table 1. Tests of main effects for sex, age and gender are shown in Table 2. Differences between cultures, represented using marginal means in Figure 1, emerged for two of the three factors and 10 of 14 dimensions. US infants were rated marginally higher on Surgency, receiving higher ratings on Activity Level and Vocal Reactivity, but lower ratings on Smiling and Laughter, than Dutch infants. US infants were also rated more highly on NEG, demonstrating higher levels of Fear, Frustration, and Sadness, and lower levels of Falling Reactivity. Dutch infants were rated higher on the ORC Factor, and on the dimensions of Cuddliness, Low-Intensity Pleasure, and Soothability associated with this factor. Age differences indicated that between 6 and 12 months of age, infants became higher in NEG and the associated dimension of Distress to Limitations. Gender effects indicated higher SUR, Approach, High-Intensity Pleasure, Distress to Limitations and Duration of Orienting in males, and higher levels of Fear among females.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of IBQ-R Factor and Dimension Scores for 6- and 12-Month-Old Infants in The Netherlands and U.S.A.

| Scale | Netherlands | U.S.A. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 6 months M (sd) |

12 months M (sd) |

6 months M (sd) |

12 months M (sd) |

|

| Surgency | 4.36 (.67) | 4.84 (.57) | 4.61 (.68) | 5.00 (.54) |

| Approach | 4.57 (1.10) | 5.35 (.83) | 4.87 (1.01) | 5.60 (.67) |

| Vocal Reactivity | 4.18 (.99) | 4.78 (.87) | 4.42 (.98) | 5.06 (.89) |

| High Intensity Pleasure | 5.62 (.75) | 5.93 (.61) | 5.62 (.78) | 5.94 (.61) |

| Smiling and Laughter | 4.88 (.95) | 4.90 (.78) | 4.50 (1.00) | 4.56 (.91) |

| Activity Level | 3.53 (.87) | 4.03 (.91) | 4.46 (.73) | 4.76 (.76) |

| Perceptual Sensitivity | 3.45 (1.21) | 4.08 (1.22) | 3.76 (1.12) | 4.07 (1.12) |

| Negative Affectivity | 2.48 (.53) | 2.80 (.58) | 3.05 (.50) | 3.49 (.57) |

| Sadness | 2.97 (.84) | 3.15 (.87) | 3.51 (.85) | 3.72 (.86) |

| Distress to Limitations | 2.74 (.73) | 3.39 (.86) | 3.54 (.68) | 4.28 (.79) |

| Fear | 1.89 (.64) | 2.41 (.88) | 2.27 (.77) | 2.98 (.93) |

| Falling Reactivity | 5.69 (.71) | 5.75 (.72) | 5.13 (.74) | 5.02 (.67) |

| Orienting/Regulatory Capacity | 5.12 (.47) | 4.91 (.59) | 4.50 (.55) | 4.35 (.52) |

| Low Intensity Pleasure | 5.42 (.70) | 5.27 (.91) | 5.04 (.76) | 4.80 (.76) |

| Cuddliness | 6.00 (.47) | 5.44 (.74) | 5.57 (.74) | 5.09 (.88) |

| Duration of Orienting | 3.65 (.89) | 3.41 (.96) | 3.83 (1.00) | 3.78 (.96) |

| Soothability | 5.40 (.78) | 5.53 (.75) | 3.57 (.71) | 3.77 (.66) |

Note: Results for factor scores presented in bold. Netherlands ns = 184 (6 months) and 172 (12 months). U.S.A. ns = 114 (6 months) and 92 (12 months).

Table 2.

Effects of Culture, Age, and Sex on IBQ-R Factors and Dimensions.

| Scale | Culture (F) | Age (F) | Sex (F) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgency | 2.79# | 1.38 | 3.88* |

| Approach | 2.53 | .70 | 4.20* |

| Vocal Reactivity | 4.81* | .19 | 1.29 |

| High Intensity Pleasure | .11 | 1.16 | 12.91** |

| Smiling and Laughter | 13.62** | 1.69 | 1.26 |

| Activity Level | 47.17** | 1.48 | .13 |

| Perceptual Sensitivity | .15 | 6.57* | 2.54 |

| Negative Affectivity | 78.64** | 6.38* | .05 |

| Sadness | 21.87** | 3.04# | .12 |

| Distress to Limitations | 67.78** | 10.76** | 4.01* |

| Fear | 35.80** | 2.03 | 7.58** |

| Falling Reactivity | 54.12** | .12 | .14 |

| Orienting/Regulatory Capacity | 83.80** | .22 | .32 |

| Low Intensity Pleasure | 20.27** | .22 | 1.22 |

| Cuddliness | 17.41** | 3.29# | .06 |

| Duration of Orienting | 2.46 | .38 | 5.22* |

| Soothability | 403.18** | .34 | .01 |

Note: Results for factor scores presented in bold. Repeated measures ANOVAs, with maternal age and education as covariates. dfs range from (1, 238) to (1, 248).

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10

Figure 1.

Marginal means, adjusted for maternal age and education, of temperament factor and scale scores for Dutch and American infants. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Culture-by-age interactions were significant for ORC, F (1, 247) = 6.45, p< .05, Duration of Orienting, F (1, 253) = 10.36, p< .01, and Fear, F (1, 246) = 4.48, p< .05. Follow-up tests indicated that Dutch infants were higher on ORC at both ages, but this effect was stronger at 6 months, F (1, 278) = 91.04, p< .01, than at 12 months, F (1, 263) = 42.26, p< .01. US infants were higher in Duration of Orienting than Dutch infants at 12 months, F (1, 262) = 8.99, p< .01, but not at 6 months, F (1, 277) = .25, p> .10. US infants were higher in Fear at both ages, but this effect was stronger at 12 months, F (1, 263) = 31.28, p< .01, than at 6 months, F (1, 277) = 25.52, p< .01. No culture-by-sex interactions were significant. Although some age-by-sex interactions were significant, because these were not relevant to our research questions, they are not reported.

Effect of Culture on Stability of Temperament

Table 3 contains Pearson’s correlations representing stability of the IBQ-R dimensions from 6 to 12 months for Dutch and US infants, and Fisher’s Z tests of differences between the coefficients obtained in the two countries. Both Smiling and Laughter and Vocal Reactivity were significantly more stable in US infants.

Table 3.

Stability of temperament from 6 to 12 months in Netherlands and US.

| Scale | Stability (correlations) from 6 to 12 months of age

|

Difference in Stability (Fisher’s Z) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands | U.S. | ||

| Surgency | .67 | .75 | 1.24 |

| Approach | .50 | .46 | −.40 |

| Vocal Reactivity | .49 | .66 | 1.96* |

| High Intensity Pleasure | .50 | .60 | 1.10 |

| Smiling and Laughter | .53 | .69 | 1.96* |

| Activity Level | .45 | .46 | .10 |

| Perceptual Sensitivity | .53 | .57 | .44 |

| Negative Affectivity | .58 | .40 | −1.82# |

| Sadness | .51 | .41 | −.97 |

| Distress to Limitations | .58 | .40 | −1.82# |

| Fear | .38 | .43 | .46 |

| Falling Reactivity | .33 | .35 | .17 |

| Orienting/Regulatory Capacity | .56 | .59 | .34 |

| Low Intensity Pleasure | .48 | .44 | −.39 |

| Cuddliness | .39 | .58 | 1.91# |

| Duration of Orienting | .42 | .54 | 1.20 |

| Soothability | .49 | .41 | −.77 |

Note: Results for factor scores presented in bold. Ns from 162 to 172 in Netherlands sample, n = 92 in US sample.

p < .05,

p < .10

Discussion

The current study was the first to examine differences in temperament, using a fine-grained parent-report questionnaire, between infants from the US and Netherlands, and to our knowledge, the first to use a longitudinal design to investigate culture as a moderator of relative stability of temperament. The results of our investigation are consistent with our expectations, based in arguments regarding parenting differences, population genetics, and in studies of older children and adults, that infants from the United States would be rated higher on all elements of NEG and certain aspects of SUR than their counterparts from the Netherlands, and also indicate that Dutch infants were rated as higher in several fine-grained traits associated with ORC. Culture also appeared to impact the pace of consolidation of temperamental characteristics, with greater stability exhibited by US than Dutch infants in Smiling and Laughter and Vocal Reactivity.

In comparison to Dutch infants, US babies were rated as more active and vocal. These findings are consistent with previous comparisons of US infants to those from other countries (i.e., Gartstein et al., 2010; Montirosso et al., 2011), as well as studies that have compared temperamental and personality differences between older children and adults from the United States and the Netherlands (Allik & McCrae, 2004; Majdandžić et al., 2009). Our results regarding Surgency-based tendencies also demonstrate the benefits of examining fine-grained traits. Specifically, although US infants were more active and vocal than those from Holland, Dutch infants demonstrated higher amounts of smiling and laughter during daily activities. It is of note that Gaias et al. (2012) similarly reported lower activity level in Finnish children, but higher positive affectivity, in Finnish infants in comparison to children and infants from the US. In comparison to US parents, Dutch parents place greater emphasis on rest and play, as opposed to US parents’ focus on cognitive stimulation (Harkness & Super, 2006; Super et al., 1996), and this systematic variability may promote different aspects of Surgency. Frequent exposure to novel and intense activities may facilitate higher optimal levels of arousal among infants raised in US homes, leading them to more actively engage their environment to raise their own arousal. In contrast, promotion of regular schedules involving a great deal of rest may allow Dutch infants to experience satisfaction at lower levels of stimulation, and the more calming home environments they encounter may elicit greater expressions of happiness in routine activities. An alternative interpretation is that these differences reflect greater perceptions of activity and approach by US parents, and perceptions of general positive affectivity by parents from The Netherlands.

More frequent displays of positive affect and contentedness during sedate activities were also revealed through Dutch infants’ higher scores on scales measuring cuddliness and low-intensity pleasure, and on the associated ORC factor. Because ORC has been suggested as a possible precursor to the personality trait of Conscientiousness, our findings can be viewed as consistent with Allik and McCrae (2004), who reported higher Conscientiousness in Dutch than U.S. adults. These findings are also reminiscent of those obtained through parents’ free reports, in which Dutch parents characterized their children as “agreeable” and “enjoying life” more frequently than parents from the US (Harkness & Super, 2006). Curiously, however, whereas Harkness and Super found Dutch parents frequently noted their children’s long attention spans, our results indicated higher duration of orienting in US infants at 12 months of age, and no effect of culture at 6 months. These apparently conflicting findings may be due to methodological discrepancies. Although the free report descriptions analyzed by Harkness and Super may have some basis in actual infant behavior, they also indicate cultural ideals regarding desirability of certain attributes. Free reports of attentional focus may additionally reflect greater frequency of opportunities for focus in Dutch homes. That is, by emphasizing rest and deemphasizing intense stimulation, parents in The Netherlands create more moments during which their children are likely to attend to a single object, such that this behavior is perceived as a salient characteristic of the children themselves.

A large cultural effect was obtained for Soothability, with Dutch infants demonstrating far greater responsivity to parental efforts to calm them. These tendencies for emotional control in response to parental soothing may pave the way for greater self-regulation of negative emotion during later infancy. Dutch infants demonstrated less frequent displays of Fear, Frustration, and Sadness, as well as faster recovery from distress than US infants, especially at 12 months. Findings of lower negative affectivity are consistent with cross-cultural adult personality research, which have indicated higher levels of Neuroticism among US adults (Allik & McCrae, 2004; Schmitt et al., 2007). They are somewhat surprising with respect to previous studies, in which US infants scored lower on Fear and Frustration, and higher on Soothability, than infants from China, Japan and Russia (Gartstein et al., 2006; 2010), but are consistent with Gaias et al. (2012), who reported higher Fear in US infants than infants from Finland, as well as reporting higher levels of Fear, Frustration, and Discomfort in older Finnish children than US youth. Collectively, the findings of these studies and the current effort suggest particularly low levels of negativity among Northern European infants. Compared to parents from other cultures, Dutch caretakers place an exceptional value on emotional closeness and interdependence and have been characterized as particularly tolerant of their children’s bids for attention (Harkness, Super, & van Tijen, 2000), perhaps demonstrating calm responsivity that often preempts displays of negative emotion. Alternatively, these findings may reflect the relative frequency of alleles associated with expression of negativity and social responsivity in the two cultures (Chiao & Blizinsky, 2010; Way & Lieberman, 2010), or may be attributed to tendencies for parents in the Netherlands to less frequently interpret mild fussing as negative affect, leading to lower ratings of infant negativity, compared to US caregivers.

Although all temperament dimensions demonstrated significant stability between 6 and 12 months of age, this consistency was more pronounced among US than Dutch infants on measures of Smiling and Laughter and Vocal Reactivity. These results suggest that influences leading to consolidation of Surgent tendencies operate earlier in the United States than in Holland. These findings require replication, but represent an intriguing new direction for longitudinal investigations of culture. Higher stability among US infants may indicate that these dimensions are emphasized earlier among US parents, and less open to change, than is the case for Dutch parents. Alternatively, the greater degree of change in Holland may suggest a degree of variability in parental ethnotheories concerning elements of Surgency that encourage modification of these traits in the Dutch culture, whereas more uniform promotion among US parents may allow early-appearing behavioral tendencies to be maintained. On a related note, parents in the US may encourage behavioral manifestations of Surgency earlier, and more consistently, than their Dutch counterparts.

Our study suggests differences between infants from the US and Netherlands on multiple dimensions, but must be considered in the context of limitations of our approach. Although we contend that the IBQ-R, because it asks parents to report on observable behaviors in specific, concrete situations, more accurately reflects infant behavior than other questionnaire or interview methods, it is possible that some temperament differences identified in this study are due to differences in ethnotheories that shape parental perceptions. Additional studies, including those utilizing observational methods, are required to confirm that the obtained effects truly reflect differences in infant behavior, rather than reflecting culturally specific response biases. A second limitation concerns sampling. Although the techniques used to recruit subjects were similar across the two samples, each was drawn from a single community, and the degree to which the caretakers and infants were representative of their respective nations remains ambiguous. Although we have interpreted our findings in relation to parental ethnotheories in the two countries, the specific locations for data collection differed between the current and previous studies, tempering these interpretations. Relatedly, the current study provides no assessment of caretaking or genetic factors representing the mechanisms through which culture is implicated in the developmental processes. Importantly, although our interpretations emphasize parenting as an influence upon temperament, it is also the case that intrinsic temperamental differences between infants can shape parental beliefs and actions (e.g., Bell, 1968). Explicit empirical connections between differences in parental ethnotheories and related infant behaviors, supported through longitudinal and/or genetically-sensitive designs, represent important future directions.

Despite these limitations, this study represents a valuable bridge between prior studies. The differences identified in infants from The Netherlands and US demonstrate considerable similarity with those emerging in adults’ reports of their own personality, are consistent with expectations from genetic distribution analyses, and resonate with thematic differences in parents’ reports of their views on socialization. Importantly, this coherent picture is apparent for countries that are quite similar with respect to their political/economic systems and historical bases. Variations between the cultures of Western countries are less dramatic than those between cultures sharing fewer common influences, yet provide a powerful lens for the examination of the developmental interplay between persons and their environments.

Acknowledgments

The Dutch research was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) by a personal Vidi Grant to C. de Weerth (grant number 452-04-320). The US research was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health Small Research Grant (R03 MH0670).

Contributor Information

Jimin Sung, Bowdoin College, USA.

Roseriet Beijers, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Maria A. Gartstein, Washington State University, USA

Carolina de Weerth, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Samuel P. Putnam, Bowdoin College, USA

References

- Allik J, McCrae RR. Towards a geography of personality traits: Patterns of profiles across 36 cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2004;35:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review. 1968;75:81–95. doi: 10.1037/h0025583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yang F, Fu R. Culture and temperament. In: Zentner M, Shiner RL, editors. Handbook of temperament. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 462–478. [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JY, Blizinsky KD. Culture-gene coevolution of individualism-collectivism and the serotonin transporter gene. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;277:529–537. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM. Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology. 1990;41:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Gaias LM, Räikkönen K, Komsi N, Gartstein MA, Fisher PA, Putnam SP. Cross-cultural temperamental differences in infants, children, and adults in the United States of America and Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2012;53:119–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00937.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Gonzalez C, Carranza JA, Ahadi SA, Ye R, Rothbart MK, Yang SW. Studying cross-cultural differences in the development of infant temperament: People’s Republic of China, the United States of America, and Spain. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2006;37:145–161. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK. Studying infant temperament via the Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development. 2003;26:64–86. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Slobodskaya HR, Kirchhoff C, Putnam SP. Cross-cultural differences in the development of behavior problems: Contributions of infant temperament in Russia and U.S. International Journal of Developmental Science. 2013;7:95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Slobodskaya HR, Zylicz PO, Gosztyla D, Nakagawa A. A cross-cultural evaluation of temperament: Japan, USA, Poland, and Russia. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2010;10:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness S, Super CM. Themes and variations: Parental ethnotheories in Western cultures. In: Chung OB, editor. Parenting beliefs, behaviors, and parent-child relations: A cross-cultural perspective. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2006. pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness S, Super CM, van Tijen N. Individualism and the “Western mind” reconsidered: American and Dutch parents’ ethnotheories of the child. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2000;87:23–39. doi: 10.1002/cd.23220008704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdandžić M, Putnam SP, Siib F, Kung J-F, Lay K-L, van Liempt I, Gartstein MA. Cross-cultural investigation of temperament in early childhood using the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Denver, CO. 2009. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Montirosso R, Cozzi P, Putnam SP, Gartstein MA, Borgatti R. Studying cross-cultural differences in temperament in the first year of life: United States and Italy. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2011;35:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Rothbart MK, Gartstein MA. Homotypic and heterotypic continuity of fine-grained temperament during infancy, toddlerhood, and early childhood. Infant and Child Development. 2008;17:387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Damon W, Lerner R, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3. Social, Emotional, and Personality Development. 6. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Gruber R, Raviv A. Sleep, neurobehavioral functioning, and behavioral problems in school-age children. Child Development. 2002;73:405–417. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt DP, Allik J, McCrae RR, Benet-Martinez V. The geographic distribution of Big Five personality traits: Patterns and profiles of human self-description across 56 nations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2007;38:173–212. [Google Scholar]

- Slobodskaya HR, Gartstein MA, Nakagawa A, Putnam SP. Early temperament in Japan, the United States, and Russia: Do cross-cultural differences decrease with age? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2013;44:438–460. [Google Scholar]

- Super CM, Harkness S, van Tijen N, van der Vlugt E, Dykstra J, Fintelman M. The three R’s of Dutch child rearing and the socialization of infant arousal. In: Harkness S, Super CM, editors. Parents’ cultural belief systems: Their origins, expressions, and consequences. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 447–466. [Google Scholar]

- Way BM, Lieberman MD. Is there a genetic contribution to cultural differences? Collectivism, individualism and genetic markers of social sensitivity. Social, Cognitive, and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;5:203–211. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]