Abstract

We present a photocathode assembly for the visible-light-driven selective reduction of CO2 to CO at potentials below the thermodynamic equilibrium in the dark. The photoelectrode comprises a porous p-type semiconducting NiO electrode modified with the visible-light-responsive organic dye P1 and the reversible CO2 cycling enzyme carbon monoxide dehydrogenase. The direct electrochemistry of the enzymatic electrocatalyst on NiO shows that in the dark the electrocatalytic behavior is rectified toward CO oxidation, with the reactivity being governed by the carrier availability at the semiconductor–catalyst interface.

Converting solar energy into storable fuels is an important option for securing future renewable energy.1 By no means a new concept – artificial photosynthesis (AP), unlike natural photosynthesis, is dedicated solely to effcient fuel formation and does not compete for untenable resources: it could work on urban rooftops.2 The modern field is very much in its infancy, as many researchers strive, piece by piece, to learn and copy the tricks that biology has perfected. The hope is that important lessons from bench-level experiments will ultimately be taken up for development. As a general rule, AP-derived fuels can either be H2, the immediate product of water splitting, or carbon compounds such as methanol. Most obviously, carbon fuels can be formed indirectly by “hydrogenation” of CO2, similar to the processes occurring in photosynthetic dark reactions; but direct reduction of CO2 is also an attractive possibility that could lead to CO2 replacing petrochemicals as the feedstock for value-added organic chemicals. Like natural photosynthesis, AP can be broken down into four essential processes: harvesting of visible light, charge (electron–hole) separation, fuel formation, and water oxidation to O2; the last two processes require an efficient and selective catalyst. It is difficult to integrate all of these processes, so researchers have streamlined efforts by focusing on individual aspects.

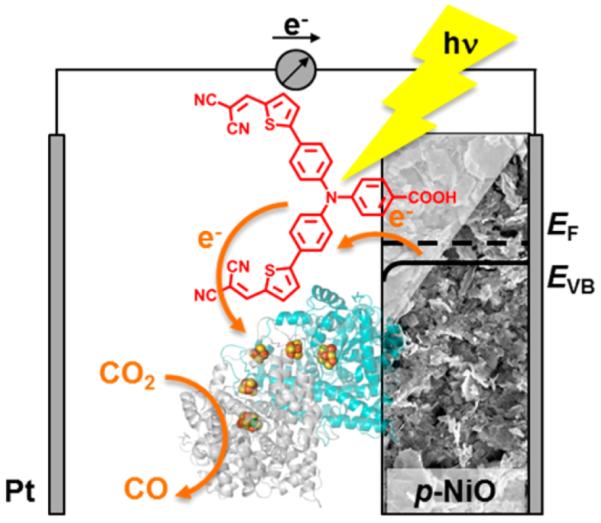

We herein address the direct reduction of CO2 to CO using a p-type semiconductor as a photocathode. Reductive CO2 activation is a fundamentally challenging process, as the simple one-electron reduction to the CO2•− radical anion (E = −1.9 V vs SHE) is highly unfavorable. In contrast, synchronous proton-coupled two-electron reduction of CO2 to CO or formate has no such energy-costing restriction.3 Selectivity is also important.4,5 With evolved active sites that are virtually perfect, it is no surprise that enzymes lead the way, and carbon monoxide dehydrogenase or formate dehydrogenase are both established as reversible electrocatalysts for CO2 cycling.6 In a wider context, little is known about electron transfer between semiconductors and reversible electrocatalysts. The photoelectrochemical cell we now describe comprises a dye-sensitized p-type NiO cathode (P1–NiO) functionalized by spontaneous adsorption of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase I from Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans (henceforth abbreviated as CODH) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme showing a photoelectrochemical cell for selective reduction of CO2 to CO at p-type NiO. Light absorption by the organic dye P1 (red) is followed by electron transfer to CODH, which is coadsorbed on the NiO surface and carries out CO2 reduction, while hole injection into the NiO valence band regenerates the P1 ground state. The porous nature of the NiO surface is indicated by the SEM image (the full image is given in the Supporting Information). The Fermi level and valence band potentials of NiO are denoted as EF and EVB.

Sun and co-workers introduced P1 as an organic photo-sensitizer for p-type dye-sensitized solar cells 7 and more recently achieved light-driven H2 evolution by coadsorbing P1 and a molecular cobalt cobaloxime catalyst on NiO.8 Taking their lead, we have adapted the concept for light-driven CO2 reduction. The mechanistic principle being exploited is that each excitation of P1 results in transfer of an electron to its coadsorbed partner CODH, passing through a relay of FeS clusters to the [Ni4Fe-4S] active site at which CO2 is converted to CO in a two-electron proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) reaction. Unlike simple molecular catalysts, enzymes such as CODH have a highly efficient active site as well as additional redox centers to capture, irreversibly,9 more than enough reducing or oxidizing equivalents needed to complete the catalytic cycle. Following each electron-transfer step, the P1 ground state is regenerated through hole injection into the NiO valence band. The relevant electrochemical potentials of the individual components are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reduction Potentials of the Individual Components of the CO2-Reducing Photocathode Assemblya

All values in V vs SHE at pH 6.

First, we studied the dark electrocatalytic activity of CODH adsorbed on a p-type NiO electrode using protein film electrochemistry (PFE), a suite of techniques that provide important mechanistic information on redox enzymes under turnover conditions.12 The turnover frequencies (TOFs) for CO2 reduction and CO oxidation achieved with CODH are unmatched by any synthetic catalyst.13

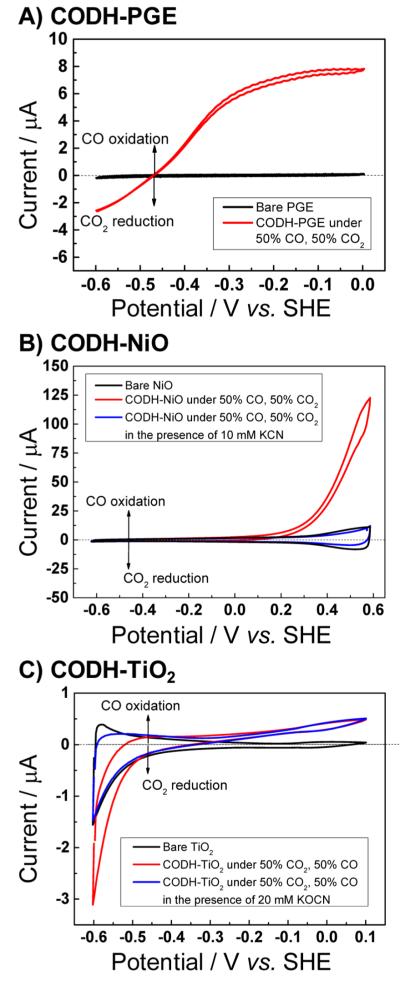

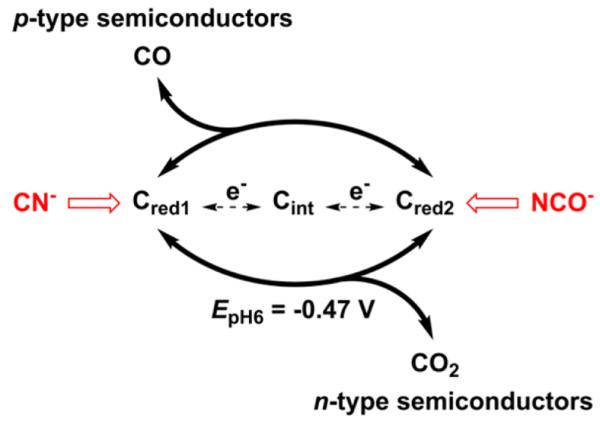

When adsorbed on a pyrolytic graphite edge (PGE) electrode, CODH displays catalytic activity for both CO2 reduction and CO oxidation (CO2 and CO are bubbled through the solution as a 50/50 gas mixture), as shown in Figure 2A. Importantly, the cyclic voltammogram (CV) cuts sharply through the zero-current axis at the thermodynamic potential. The active site alternates between two catalytically active states Cred1 and Cred2 that are separated by two electrons (Scheme 1), with Cint as an intermediate formed during long-range electron transfers from the FeS clusters.

Figure 2.

Cyclic voltammograms of CODH adsorbed on (A) PGE, (B) NiO, and (C) TiO2. Current–potential curves of the bare electrodes are depicted in black; experiments with adsorbed CODH (recorded with a 50% CO/50% CO2 gas mixture bubbling through the cell) are shown in red. The blue CVs in (B) and (C) were recorded in the presence of 10 mM KCN (B) and 20 mM KOCN (C). Other conditions: T = 20 °C, 0.2 M MES buffer (pH 6), scan rate = 10 mV s−1. (A) and (C) are adapted from ref 15.

Scheme 1.

Redox Statesa Involved in Catalytic CO2 Interconversion at the Active Site of CODH and How p-Type and n-Type Semiconductors Rectify Catalytic Electron Flow

aCred1 and Cred2 are the catalytically active states that effect CO oxidation and CO2 reduction, respectively. The transient Cint state participates in the half-cycle regeneration of these active states. The small-molecule inhibitors CN− and NCO− selectively intercept states Cred1 and Cred2 and inhibit CO oxidation (CN−) and CO2 reduction (NCO−).14

In contrast to the reversible catalytic interconversion of CO2 and CO observed on the metallic-type PGE electrode, CODH behaves as a unidirectional CO oxidizer (Figure 2B, red trace) when attached to NiO; in other words, the otherwise bidirectional catalysis is rectified. Indeed, a catalytic oxidation current is observed only upon application of an overpotential of approximately 0.6 V. (Under such oxidizing conditions, CODH converts slowly to the inactive Cox state14). To prove that the oxidation current stems from catalytic turnover, KCN was injected into the cell (to a final concentration of 10 mM; Figure 2B, blue voltammogram). Cyanide, which is isoelectronic with CO, targets the Cred1 state of CODH (Scheme 1), thereby selectively inhibiting CO oxidation;14 the voltammogram thus obtained resembles the baseline (bare NiO). The results mirror recent observations15 with CODH adsorbed on the n-type materials TiO2 and CdS, as illustrated in Figure 2C, which shows cyclic voltammograms of CODH adsorbed on TiO2 recorded under conditions identical to those for the voltammograms displayed in Figure 2A,B. In contrast to p-NiO, CO oxidation at n-TiO2 is barely detectable, whereas a strong reduction current is observed; this is established to be CO2 reduction by the introduction of cyanate (NCO−, isoelectronic with CO2), which targets the Cred2 state and blocks CO2 reduction (see Scheme 1 and the blue trace in Figure 2C).

The results highlight the concept that the activity of an electrocatalyst attached to a semiconductor depends greatly on the properties of that semiconductor: the resulting rectification in either direction, depending on choice of semiconductor, is evident only when an electrocatalyst that otherwise behaves reversibly is used.15 The surface concentration of the majority carriers in a semiconductor depends exponentially on the difference between the applied potential E and the flatband potential Efb.16 The catalytic directionality enforced on n-type TiO2 coincides with a change in carrier availability around the flatband potential of the semiconductor [Efb (TiO2) ≈ −0.50 V vs SHE at pH 6].15 In chemical terms, some Ti4+ sites are reduced to Ti3+. In contrast, p-type NiO (Efb ≈ 0.61 V vs SHE at pH 6)11 forms a depletion layer at potentials negative of Efb, which acts as a barrier for electron transfer from the semiconductor to the catalyst, blocking CO2 reduction. As Efb is approached, the conductivity of NiO increases exponentially, allowing CO oxidation catalysis to occur. In chemical terms, some Ni2+ sites are oxidized to Ni3+. This effect is reflected in a steep increase in the catalytic oxidation current in Figure 2B positive of ca. 0.3 V vs SHE, i.e., relatively close to Efb.

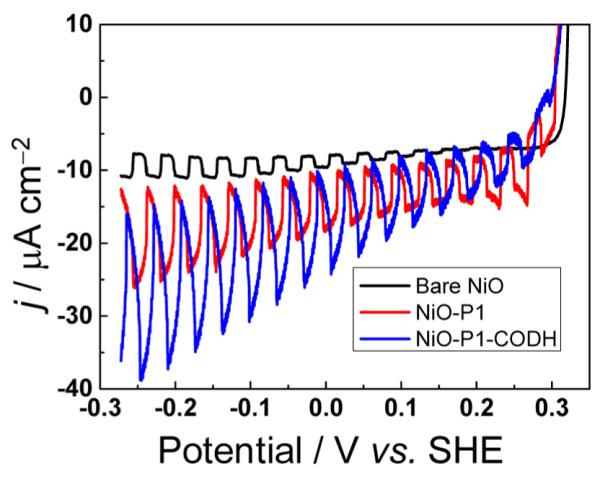

Having established the electroactivity of CODH on NiO, we sensitized the semiconductor with the visible-light-absorbing dye P1 [see the Supporting Information (SI) for experimental details]. The synthesis of P1 was carried out as described previously.7 Figure 3 shows linear sweep voltammograms recorded under chopped illumination in CO2-saturated buffer (cyclic voltammograms of NiO–P1 are depicted in Figure S5 in the SI). Bare NiO shows very little photocurrent because of its large band gap of 3.6 eV (black current–potential curve). Upon sensitization with P1, the photocurrent increases, since P1 is capable of absorbing visible light (λmax = 550 nm in solution and 500 nm when adsorbed on NiO).7 Modification with CODH results in a further photocurrent enhancement, which we ascribe (see below) to the light-driven reduction of CO2. Photoexcited P1 provides sufficient driving force to effect CO2 reduction catalyzed by CODH (see Table 1) but does not reduce CO2 itself. The LUMO of P1 lies ca. 0.7 V lower in energy than the CO2/CO2•− redox couple: importantly, as a single-electron-transfer dye that is not capable of accumulating a second electron, P1 cannot undergo the PCET reactions that are required to lower the activation barrier for CO2 activation, in contrast to CODH (which easily accumulates the two electrons needed).

Figure 3.

Linear sweep voltammograms of NiO (black), NiO–P1 (red), and NiO–P1–CODH (blue) recorded under chopped illumination (0.5 Hz, 45 mW cm−2) and CO2 flow. Other conditions: 0.2 M MES buffer (pH 6), T = 32 °C, scan rate = 10 mV s−1.

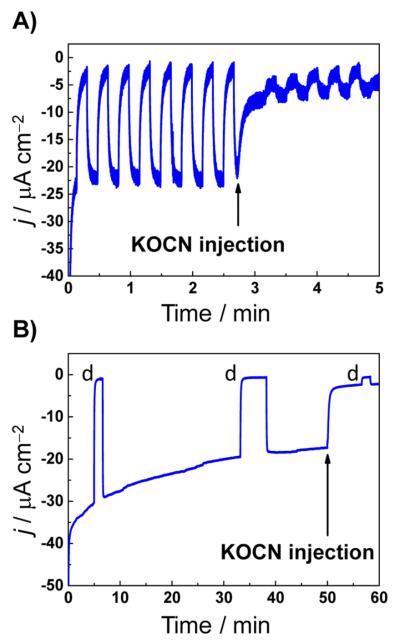

To verify that the photocurrent enhancement we observed upon adsorption of CODH on NiO–P1 is due to catalytic conversion of CO2 to CO, we once again used NCO− as a selective inhibitor of CO2 reduction.17 Figure 4A depicts transient photocurrents of NiO–P1–CODH recorded at −0.27 V vs SHE (pH 6), which represents a 0.2 V underpotential with respect to CO2 reduction in the dark. The photocurrent decreases significantly upon introduction of 60 mM KOCN, which establishes that the major proportion of the observed photocurrent stems from CO2 reduction. Control experiments in the absence of CODH (i.e., NiO–P1 only) showed that injecting KOCN had no effect on the photocurrent (Figure S7).

Figure 4.

Chronoamperometry experiments on NiO–P1–CODH under a flow of CO2 with the potential held at −0.27 V vs SHE. Potassium cyanate (KOCN) was injected to a final concentration of 60 mM. (A) Transient photocurrents under chopped illumination. (B) Continuous illumination to assess the stability of the photocathode assembly under turnover conditions; “d” represents dark intervals. The experiments were carried out under white-light illumination (45 mW cm−2) and CO2 flow in 0.2 M MES buffer (pH 6) at T = 32 °C.

Having identified the nature of the photocurrent, we assessed the stability of CO2 reduction. Figure 4B depicts the temporal behavior of the catalytic current produced by NiO–P1–CODH during prolonged illumination (dark intervals are indicated by the letter “d”). The assembly shows good stability until cyanate is injected, analogous to the experiment depicted in Figure 4A, again demonstrating the catalytic turnover of the photocathode–catalyst system. Both Figures 3 and 4 strongly support a mechanism analogous to that described by Sun and co-workers for H2 production.8 In our system, P1 acts as a visible-light-responsive sensitizer that generates excited-state electrons, transfers these to CODH for catalysis, and is regenerated via hole injection into NiO.

In conclusion, catalytic electron flow through the CO2-reducing enzyme CODH, which behaves as a reversible catalyst on a metallic electrode, is rectified when CODH is attached to n-type (CO2 reduction) or p-type (CO oxidation) semiconductors. When NiO is sensitized with the dye P1, a photocathode is produced that selectively reduces CO2 to CO under visible-light illumination and application of a mildly reducing potential. The assembly shows good stability under turnover conditions, indicating that it could be coupled with a photoanode for water oxidation in a tandem photoelectrochemical cell to close the photosynthetic cycle. These experiments are currently in progress. Although not suitable for large-scale applications, reversible and highly selective electrocatalysts such as CODH are valuable model catalysts for AP. They serve as depolarizers that overcome the kinetic burden of sluggish catalysis and therefore allow the study of other mechanistic bottlenecks in operando. For example, rectification of catalytic electron transport at a semiconductor is revealed only by using a catalyst that is otherwise reversible. Multicentered enzymes, which have well-defined and stable active sites, have a special ability to accumulate electrons, a property that is less likely for simple catalysts but likely to be very important in competing with recombination.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Biological and Biotechnological Sciences Research Council (Grants BB/H003878-1, BB/I022309-1, and BB/L009722/1 to F.A.A.) and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (Supergen V Grant EP/H019480/1 to F.A.A.). A.B. acknowledges St. John’s College Oxford for a St. John’s College Graduate Scholarship. F.A.A. is a Royal Society-Wolfson Research Merit Award holder. The authors thank Prof. Michael Hayward, Dr. Malcolm Stewart, and Prof. Jamie Warner for providing access to a high-temperature furnace, synthetic equipment, and SEM, respectively.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Full materials and methods; NiO and P1 synthesis and characterization; electrode fabrication; (photo)electrochemical methods and equipment. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewis NS, Nocera DG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:15729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603395103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciamician G. Science. 1912;36:385. doi: 10.1126/science.36.926.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson EE, Kubiak CP, Sathrum AJ, Smieja JM. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:89. doi: 10.1039/b804323j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu W, Michalsky R, Metin Ö, Lv H, Guo S, Wright CJ, Sun X, Peterson AA, Sun S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:16833. doi: 10.1021/ja409445p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar B, Llorente M, Froehlich J, Dang T, Sathrum A, Kubiak CP. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2012;63:541. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032511-143759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachmeier A, Siritanaratkul B, Armstrong FA. In: From Molecules to Materials–Pathways to Artificial Photosynthesis. Rozhkova EA, Ariga K, editors. Springer; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin P, Zhu H, Edvinsson T, Boschloo G, Hagfeldt A, Sun L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8570. doi: 10.1021/ja8001474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Duan L, Wen F, Li C, Wang M, Hagfeldt A, Sun L. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:988. doi: 10.1039/c2cc16101j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilker MB, Shinopoulos KE, Brown KA, Mulder DW, King PW, Dukovic G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:4316. doi: 10.1021/ja413001p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin P, Wiberg J, Gibson EA, Linder M, Li L, Brinck T, Hagfeldt A, Albinsson B, Sun L. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:4738. [Google Scholar]

- 11.He J, Lindström H, Hagfeldt A, Lindquist S-E. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2000;62:265. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vincent KA, Parkin A, Armstrong FA. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4366. doi: 10.1021/cr050191u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Can M, Armstrong FA, Ragsdale SW. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:4149. doi: 10.1021/cr400461p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang VCC, Can M, Pierce E, Ragsdale SW, Armstrong FA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:2198. doi: 10.1021/ja308493k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachmeier A, Wang VCC, Woolerton TW, Bell S, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Can M, Ragsdale SW, Chaudhary YS, Armstrong FA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:15026. doi: 10.1021/ja4042675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications. 2nd John Wiley & Sons Inc.; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Because of the minute amounts of enzymes on the electrode surface (pmol), even prolonged illumination over several hours did not produce enough CO to allow detection by gas chromatography (see Figure S6)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.