Abstract

Objectives

Emotion processing, supported by fronto-limbic circuitry known to be sensitive to the effects of aging, is a relatively understudied cognitive-emotional domain in geriatric depression. Some evidence suggests that the neurophysiological disruption observed in emotion processing among adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) may be modulated by both gender and age. Therefore, the present study investigated the effects of gender and age on the neural circuitry supporting emotion processing in MDD.

Design

Cross-sectional comparison of fMRI signal during performance of an emotion processing task.

Setting

Outpatient university setting.

Participants

One hundred adults recruited by MDD status, gender, and age.

Measurements

Participants underwent fMRI while completing the Facial Emotion Perception Test (FEPT). They viewed photographs of faces and categorized the emotion perceived. Contrast for fMRI was of face perception minus animal identification blocks.

Results

Effects of depression were observed in precuneus and effects of age in a number of fronto-limbic regions. Three-way interactions were present between MDD status, gender, and age in regions pertinent to emotion processing, including frontal, limbic and basal ganglia. Young women with MDD and older men with MDD exhibited hyperactivation in these regions compared to their respective same-gender healthy comparison (HC) counterparts. In contrast, older women and younger men with MDD exhibited hypoactivation compared to their respective same-gender HC counterparts.

Conclusions

This the first study to report gender- and age-specific differences in emotion processing circuitry in MDD. Gender-differential mechanisms may underlie cognitive-emotional disruption in older adults with MDD. The present findings have implications for improved probes into the heterogeneity of the MDD syndrome.

Keywords: emotion processing, depression, fMRI, gender, age

Objective

Individuals with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) exhibit emotion processing inefficiencies, including recognizing facial emotions (1), reflecting potential dysfunction in neural pathways supporting these processes. Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated distinct patterns in the neural circuitry supporting emotion processing in MDD, affecting limbic, basal ganglia, and cortical (e.g., insula, cingulate, fusiform, frontal) regions (e.g., 2, 3). Substantial variability is apparent across these studies with regard to regions affected and direction of differences (e.g., hyperactivation (2) versus hypoactivation (4)) compared to healthy comparison (HC) participants. Although the source of variability in those findings is unknown, methodological differences are common. Studies have varied with regard to task design (e.g., implicit vs. explicit paradigms) and regions investigated. Studies have also varied with regard to illness characteristics (e.g., phase of illness, severity) and demographic (e.g., gender, age) composition of participants included in study samples. Many studies included a greater proportion of women than men in MDD samples, reflecting the greater prevalence of MDD in women (5). Although samples are typically roughly balanced in the proportion of men and women, this procedure does not identify, and may mask, potential gender-specific neural circuit disruptions in MDD.

There is compelling evidence for gender-specific neural circuit disruption underlying emotion processing in MDD. Gender-specific decrements in facial emotion perception accuracy in MDD have been reported (6): Women with MDD were less accurate at detecting emotions than both HC women and men with MDD, whereas men with MDD performed similarly to HC men. Furthermore, gender differences in emotion recognition accuracy in healthy adults are well-established, favoring women (7), as well as in the neural circuitry supporting emotion processing (8, 9). These findings, combined with evidence for gender-specific disruption in emotion processing accuracy in MDD, underscore the critical need to evaluate the role of gender in disrupted emotion processing in MDD. The term gender is used rather than sex in the present study to reflect the range of possible biological and sociocultural contributions to these differences.

Age also has a high likelihood of impact upon facial emotion processing in MDD. Healthy older adults are less accurate at recognizing emotional expressions than younger adults and tend to categorize emotions as positive (10, 11). Older adults also exhibit reduced limbic and greater cortical activation (e.g., insula, frontal cortex; 12, 13) during facial emotion processing compared to younger adults. Due to these effects upon emotion processing in healthy aging, advanced age may conceivably increase burden on emotion processing in late-life MDD. Only two studies to date have investigated emotion processing in late-life depression. One pilot study (14), composed exclusively of thirteen women with late-onset depression compared to older HC women, reported reduced engagement of the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (PFC) during emotional evaluation of emotionally-valenced words. The second (15) used a region-of-interest analysis of twenty-seven older adults with primarily late-onset MDD (64 percent women), showing increased subgenual anterior cingulate and insula activation relative to thirty-three HC older adults.

These initial studies suggest that disruption in emotion processing circuitry continues in MDD into late life. Importantly, no studies have addressed whether emotion processing circuitry disruptions are similar in young and older adults with MDD, and none have systematically evaluated the influence of gender. Supporting the need for such a study, age and gender each have been shown to be determinants of behavioral decrements in face emotion processing accuracy in MDD (16), such that women with MDD performed more poorly than HC women in both young and older adults, whereas men with MDD performed more poorly than HC men only within older adults. Furthermore, older men may be differentially vulnerable to structural abnormalities compared to older women with MDD, including white matter hyperintensities and frontal volume loss (17, 18). Taken together, gender and age are known to influence emotion processing accuracy in healthy adults, and to influence emotion processing accuracy in adults with MDD. However, it is unknown how these characteristics together affect the neural circuitry supporting emotion processing in MDD, which was the aim of the present study. It was hypothesized that gender and age each would moderate the effects of MDD on the neurophysiology of emotion processing. Because of the paucity of data addressing this topic, we could not offer specific directional hypotheses for MDD by gender or age.

Methods

Participants

One-hundred-ten adults, including 53 with MDD and 57 HC in younger and older age groups (Table 1) were recruited through geriatric psychiatry and primary care clinics, research volunteer databases, and community advertisements. Exclusionary criteria included contraindications for MRI, uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes, any neurological disorder, head injury with loss of consciousness of > 5 minutes, and major medical conditions that could affect the central nervous system. Participants were also excluded based upon any history of psychotic symptoms, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, current substance use disorder or history of substance dependence within 5 years of the MRI. Within the older MDD group, individuals with an age of onset after 45 years were excluded to minimize the likelihood of physiological/acquired contribution to disease pathogenesis. Individuals were not excluded on the basis of taking psychotropic medications, although those using PRN anxiolytics were asked to refrain from use 24 hours prior to the scan. HC participants were free from a personal history of psychiatric illness. MDD participants were diagnosed according to the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV criteria (SCID-IP/NP; 19). Depression severity was measured with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression–Second Edition (20). Potential participants were specifically recruited in order to meet minimum cell sizes of twelve for subgroups.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistic Comparing Demographic, Medical, and Performance Characteristics for Participants with Major Depressive Disorder (n = 53) and Healthy Controls (n = 57) Grouped by Age (Younger and Older) and Gender.

| Variables | Younger

|

Older

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDD

|

HC

|

MDD

|

HC

|

|||||

| Women (n = 15) | Men (n = 12) | Women (n = 19) | Men (n = 13) | Women (n = 12) | Men (n = 14) | Women (n = 12) | Men (n = 13) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Age1 | 29.2 (7.8) | 25.5 (3.5) | 26.4 (7.7) | 24.0 (6.0) | 64.8 (6.3) | 66.0 (9.6) | 69.2 (8.6) | 67.1 (8.2) |

| Education1 | 16.2 (2.4) | 16.5 (1.9) | 15.9 (2.5) | 15.2 (2.1) | 15.4 (2.2) | 16.1 (2.8) | 17.1 (1.5) | 16.4 (2.4) |

| HDRS1 | 17.4 (4.3) | 14.8 (4.4) | 0.5 (0.8) | 1.3 (1.7) | 16.3 (6.3) | 14.6 (4.4) | 0.6 (0.8) | 1.2 (1.1) |

| HDRS: Range of scores | 12–25 | 7–21 | 0–2 | 0–5 | 7–27 | 6–24 | 0–2 | 0–3 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index1 | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.3) |

| Years of illness (MDD only)1 | 9.2 (8.8) | 8.9 (5.3) | NA | NA | 40.5 (12.3) | 42.9 (17.3) | NA | NA |

| On psychotropic medication (%) | 60 | 20 | NA | NA | 75 | 84 | NA | NA |

| Diabetes (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Hypertension (n) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 4 |

| Sleep apnea (n) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Heart condition (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| FEPT Task Accuracy (% correct)2 | 85.3 (7.8) | 82.3 (5.6) | 86.9 (5.7) | 87.7 (5.9) | 73.8 (9.1) | 80.1 (9.4) | 77.2 (6.7) | 74.8(8.5) |

Note. MDD = Major Depressive Disorder. HC = Healthy Comparison. HDRS= Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. FEPT = Facial Emotion Perception Test.

All ps > .05: age within age group (younger, F(3, 55) = 1.49, p = .23; older, F(3, 47) = .61, p = .61); education (F(7, 102) = .85, p = .55) and Charlson (F(7, 101) = 1.51, p = .17) across entire sample; Hamilton Depression Rating Scale within the MDD group (F(3, 49) = 1.02, p = .39), and years of illness between men and women within the younger (t(23) = −.08, p = .94) and older (t(24) = .39, p = .70) MDD groups separately. Data on medical conditions were missing from 10 young HC participants. Years of illness was missing from two younger MDD participants. HDRS was missing for 7 HC participants.

F(7, 102) = 7.30, p <.001. Posthoc analyses included in the supplemental text.

Procedure

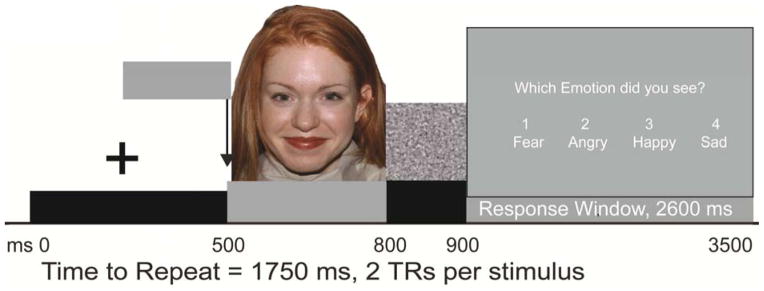

The Facial Emotion Perception Test (FEPT; Figure 1; 21, 22) was completed in the fMRI scanner. Details regarding this task have been published elsewhere (2, 23). Briefly, participants viewed photographs of faces and were required to categorize each into one of four emotions (i.e., happy, sad, angry, fearful). As a control task, blocks of animal photographs were presented, requiring categorization into one of four categories (i.e., dogs, cats, primates, birds). Functional neuroimaging acquisition parameters were consistent with prior studies in our laboratory (e.g., 2, 9, 23).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Facial Emotion Perception Test (FEPT). Presentation begins with fixation cross (+) followed by 300 ms presentation of face (or animal), then 100 ms mask, followed by a 2600 ms response window.

Analysis

Imaging data were screened for data corruption. Participants were excluded for extensive signal loss due to signal distortion (n = 6 MDD), excessive movement (n = 3 HC), and unusual head shape resulting in data loss (n = 1 HC). All analyses were conducted with the remaining 100 participants. fMRI data were evaluated with a block design using a 2 (MDD/HC) by 2 (gender) by 2 (age group) ANOVA, with the Faces minus Animals contrast as the dependent variable. Significance thresholds were derived with AlphaSim (24) (p < .005, k > 55). Post hoc, exploratory analyses were conducted using extracted data from significance maps using MarsBaR. Activation maps for the Animals-only contrast were superimposed upon the activation maps for the Faces minus Animals contrast for each result to exclude the control condition as a source of activation difference. Overlap between Animals and Faces-Animals was absent from nearly all contrasts - accept effects of age - and noted in the tables.

Results

The ANOVA demonstrated modest main effects of MDD status, gender, and age group (Table 2). Two regions had a significant interaction between MDD status and age group, and four regions had a significant interaction between gender and age group (Table 3). There were no regions significant for an MDD status by gender interaction. A three-way interaction between MDD status, gender, and age group was present in seven regions (Table 3).

Table 2.

Regions Significantly Associated with Main Effects of MDD, Gender and Age Group

| Lobe | Gyrus | BA | mm3 | x | y | z | Z | Group Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Main effect of MDD | |||||||||

| Parietal | Precuneus | 7 | 472 | 20 | −65 | 46 | 3.49 | D < C | |

| Main Effect of Gender | |||||||||

| Temporal | Middle temporal | 19 | 888 | −40 | −42 | −2 | 3.50 | W > M | |

| Occipital | Fusiform | 19 | 608 | −38 | −73 | −11 | 4.26 | W > M | |

| Main Effect of Age | |||||||||

| Frontal | Inferior Frontal1 | 47 | 536 | 40 | 34 | 1 | 3.57 | Y > O1 | |

| Occipital | Cuneus/Lingual1 | 17/18 | 4496 | 17 | −79 | 8 | 7.98 | Y > O1 | |

| Occipital | Lingual1 | 18 | 808 | −13 | −73 | 1 | 3.73 | Y > O1 | |

| Posterior | Pyramis1 | 1192 | −20 | −73 | −29 | 3.41 | Y > O1 | ||

Note. D= Major Depressive Disorder. C= Healthy Comparison.

Animals condition only O > Y.

Table 3.

Regions Significantly Associated with Interactions between MDD Status, Gender, and Age Group.

| Lobe | Gyrus | BA | mm3 | x | y | z | Z | Contrast of interest | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| MDD by Age Group Interaction | |||||||||||

| Frontal | Precentral | 6 | 512 | 15 | −19 | 59 | 3.63 | YD = YC | −1.38 | 52 | .174 |

| OD < OC | 3.95 | 44 | .001 | ||||||||

| Posterior | Cerebellum; dentate | 664 | −15 | −60 | −19 | 3.83 | YD > YC | −3.01 | 52 | .004 | |

| OD < OC | 2.68 | 44 | .010 | ||||||||

| Gender by Age Group Interaction | |||||||||||

| Frontal | Middle Frontal2 | 9 | 488 | 41 | 28 | 26 | 3.05 | YW > YM | 2.95 | 52 | .005 |

| OW ≤ OM | −1.66 | 44 | .105 | ||||||||

| Frontal | Precentral | 13/43 | 680 | −31 | −7 | 29 | 3.37 | YW > YM | 2.42 | 52 | .019 |

| OW < OM | −3.97 | 44 | .001 | ||||||||

| Subcortical | Claustrum/Insula | 560 | −31 | 6 | −9 | 3.22 | YW ≥ YM | 2.41 | 49.89 | .020 | |

| OW < OM | −3.11 | 44 | .003 | ||||||||

| Subcortical | Pulvinar | 3704 | 3 | −32 | 16 | 4.15 | YW > YM | 2.04 | 52 | .046 | |

| OW < OM | −2.88 | 44 | .006 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| MDD by Gender by Age Group Interaction | |||||||||||

| Frontal | Cingulate/Middle frontal | 32 | 1464 | −20 | 20 | 32 | 3.66 | ||||

| Frontal | Inferior Frontal | 47 | 472 | 38 | 26 | −6 | 3.28 | ||||

| Frontal | Inferior Frontal | 9 | 504 | 45 | 12 | 29 | 3.09 | ||||

| Frontal/Subcortical | Inferior Frontal/Putamen | 13 | 920 | 36 | 10 | −7 | 3.39 | ||||

| Frontal | Middle Frontal | 8 | 2368 | 24 | 16 | 36 | 3.90 | ||||

| Frontal | Superior Frontal | 9 | 616 | 20 | 39 | 35 | 3.28 | ||||

| Limbic | Cingulate | 23 | 1328 | −4 | −11 | 22 | 3.84 | ||||

Note. Y = Younger, O = Older, W = Women, M = Men, D = Major Depressive Disorder, C = Healthy Comparison. Contrasts of interest for regions significant for the 3-way interaction are detailed in Supplemental Table 1. Effect sizes and post-hoc testing were conducted with extracted data from clusters that met height by threshold whole-brain correction in the main analysis.

Significant MDD x gender x age group interaction, F(1, 92) = 3.99, p = .049.

The precuneus was less active in MDD relative to comparison participants, women activated temporal/occipital regions more than men, and there were four regions more active in younger than older adults (Table 2). Two clusters (precentral gyrus and dentate of cerebellum) were significant for an interaction between MDD status and age group (Table 3). For the precentral gyrus cluster, there was a nonsignificant effect of MDD status in the young group, whereas the MDD sample exhibited less activation than HC in the older group. For the dentate cluster, there was greater activation in MDD than in HC in the young group and less activation in MDD as compared to the HC group within the older group.

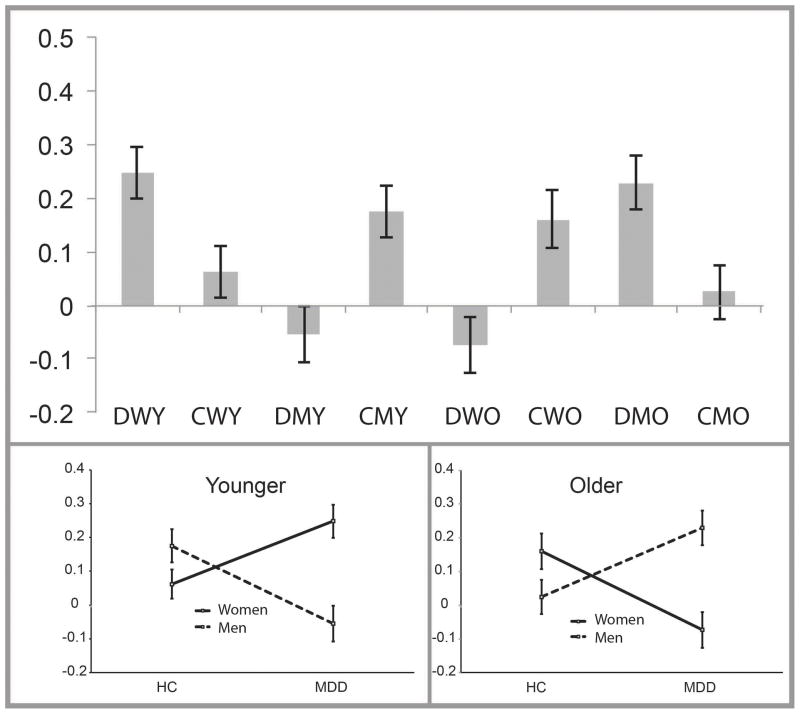

Regions significant for the interaction between MDD status, gender, and age group included clusters in the inferior, middle, and superior frontal gyri, cingulate, and putamen (Table 3; Figure 2). Post hoc analysis with activation data extracted with MarsBaR revealed that for young adults, the interaction between MDD status and gender was significant for all seven clusters (Supplemental Table 1). Within young women, activation in the MDD sample was significantly greater than the HC sample for four of the seven clusters, with the same directionality of results (MDD > HC) for the remaining non-significant clusters. Within young men, the MDD sample exhibited significantly less activation than the HC group in three of the seven clusters, with the same directionality (MDD < HC) in the remaining clusters. In the older adults, activation was significantly less in MDD women as compared to HC women in five of the seven clusters, with the same directionality (MDD < HC) in the remaining clusters. Within older men, activation was significantly greater in MDD participants relative to HC participants in two of the seven clusters, with the same directionality (MDD > HC) in the remaining clusters. Because consistent patterns between groups were present across these clusters in the main and subordinate interactions, activation values for each of the seven clusters were averaged into one value for the purpose of illustration (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure 1 displays individual activation).

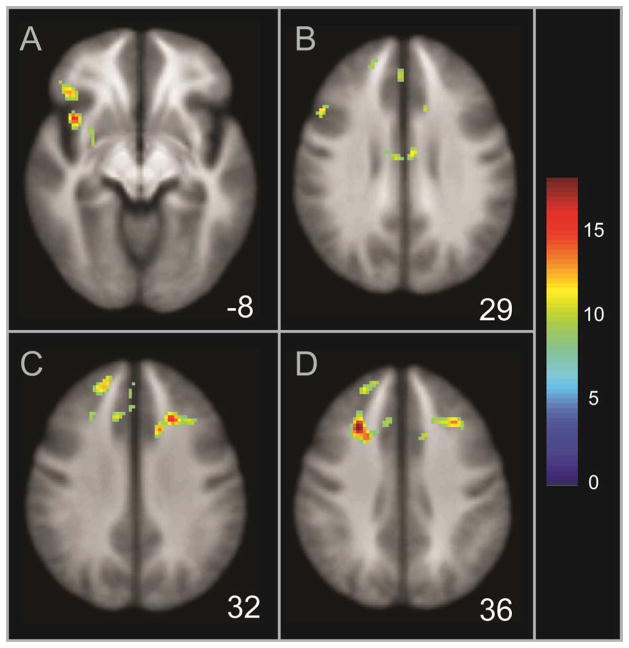

Figure 2.

Illustration of regions significant for an interaction between MDD status, gender, and age group during facial emotion processing, including the inferior frontal gyrus and putamen (Panel A), inferior/middle frontal gyrus and cingulate (Panel B), middle and superior frontal gyri (Panel C), and middle frontal gyrus/cingulate and superior frontal gyrus (Panel D). The z coordinate is displayed in the Talairach system; the scale displays corresponding F values.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the averaged extracted activation signal for the areas significant for the MDD status by gender by age group interaction. Top panel displays activation across each of the eight subgroups; the bottom two panels display these values separated by young and older subgroups. Note. Group status: D = Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), C = Healthy Comparison; W = Women, M = Men; Y = Younger, O = Older. Error bars indicate +/− 1 SEM.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that gender and age are pertinent issues to consider among depressed adults and are potentially confounding to the interpretation of data related to emotion processing circuitry and function in MDD. Young women with MDD demonstrated hyperactive emotion processing circuits, particularly within the right prefrontal cortex, compared to HC young women. In contrast, young men with MDD demonstrated hypoactivation compared to young HC men in these regions. The opposite pattern of results was evident in older adults: older women with MDD exhibited hypoactivation compared to older HC women; older men with MDD exhibited hyperactivation compared to older HC men. It is important to note that when these subgroups defined by age and gender were combined into a single group, effects of MDD appeared negligible, as they were obscured by the underlying gender- and age-specific processes in MDD.

The present study is the first to investigate the neural circuitry underlying emotion processing in older adults with early-onset, recurrent MDD. This population is relatively understudied in fMRI investigations, and there have been only two studies to date investigating emotion processing circuitry in individuals with late-life MDD (14, 15), composed primarily of women, and those with late-onset MDD. The present study found that in older adults with MDD, there were gender-specific effects that were opposite those observed in younger adults with MDD. Due to the small group sizes, especially given the known heterogeneity in late-life depression, these findings must be replicated. Longitudinal investigation of facial emotion processing with adults with MDD throughout the age spectrum would be informative in clarifying the nature of age-specific inversions of MDD by gender effects.

Regions in the present study that were observed to vary in activation based upon MDD status, gender, and age group have been described by prior research as central to facial emotional processing, in the disease expression of MDD, and in top-down regulation of affect. The IFG has been shown to be important for facial emotion processing in healthy adults (25) and is aberrantly active during emotion processing in MDD (2). The IFG is involved in inhibitory control (26) and in the regulation of negative affect (27). Our group (2) reported that greater right-versus-left activation of the IFG in women with MDD was associated with increased accuracy in facial emotion processing, suggesting that the IFG plays a compensatory role in emotion processing among women with MDD. The middle and superior frontal gyri and cingulate are associated with facial emotion processing (25, 27) and the superior frontal gyrus and cingulate are involved in regulating negative affect (29). The putamen’s role in facial emotion processing may relate to preparing for and coordinating responses to emotional stimuli (8, 28). These critical emotion processing and regulation areas demonstrate age and gender sensitivity, suggesting that even matching for age and gender may obscure gender- and age- specific processes.

Hypothesized mechanisms for aberrant activation patterns by gender and age in MDD

Young women with MDD exhibited hyperactivation in frontal, basal ganglia and limbic areas compared to young HC women, reflecting a pattern that has been frequently reported (2, 3) but not previously revealed to be gender- and age- specific. Hypotheses for processes underlying hyperactive emotion processing circuitry include heightened sensitivity to affective material, difficulty regulating emotional response to affective stimuli, and increased recruitment of resources to support performance (2). Hypoactivation, less frequently reported in related prior studies (4), has been hypothesized to reflect dysregulated functional connectivity or underlying structural dysfunction.

With regard to the compensation hypothesis, similar to hypotheses in the healthy aging literature (30), utilization of neural resources to support task performance may depend on the relationship between task demands and neural resource capacity. As task difficulty increases, recruitment of neural resources may also increase until it reaches its maximum capacity, after which activation plateaus or drops to reduced levels. Young women and older men with MDD may have been able to recruit additional neural resources to support performance, whereas young men and older women with MDD may have exceeded their capacity to support a highly demanding task, resulting in reduced activation.

Differential recruitment patterns, particularly within the prefrontal system, may also reflect gender- and age- differential emotion regulation strategies in healthy and MDD adults. For example, women are more likely than men to ruminate as a coping strategy, which has been hypothesized to be associated with the greater prevalence of MDD in women than in men (31). Rumination has been positively related to neural responses to negative facial emotions and negatively related to positive emotions in remitted MDD (32). The current study did not specifically investigate rumination or activation to negative emotions. However, approximately two-thirds of the facial emotions in the present design were negative, indicating that activation differences were likely driven more by negative than positive/neutral emotional content.

Men, in contrast, tend to be less emotionally focused (e.g., 7) and are more likely to cope through distraction than are women (e.g., 33). Some evidence suggests a link between disengagement coping and depressive symptoms (34). Alexithymia, more common in men and related to depressive symptoms (35), is related to reduced activity of neural regions supporting emotion processing (36). As such, different emotion regulation strategies associated with MDD in men (difficulty maintaining engagement with processing of affective material) and women (difficulty disengaging from processing of affective material) could result in discrepant patterns of activation supporting facial emotion processing.

Aging is associated with a tendency to be less emotionally reactive and with a bias towards positive emotions (e.g., 37). One study (38) reported that increasing emotional stability in later life was associated with greater medial prefrontal control over negative emotional stimuli. Other studies (e.g., 13) have found that healthy older adults recruit greater frontal and less limbic regions during emotion processing compared to younger adults. One study (39) reported distraction to be superior to reappraisal as an effective emotion regulation strategy in older adults with MDD. In older adults, women are more likely than men to utilize suppression as a regulation strategy, which is associated with depressive symptoms (40). Emotion suppression during memory encoding has been related to reduced functional connectivity of hippocampus and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (41). Altered connectivity of prefrontal regulatory regions during an emotion regulation task has been shown in older adults with genetic susceptibility to depression (42). As such, altered engagement of prefrontal regulatory regions may be partially explained by gender differences in emotion regulatory strategies in older adults. Chronic MDD is likely to interfere with these aspects of the healthy aging process and with emotion regulation strategies.

General effects of MDD

When the overall effect of MDD status was evaluated without regard to age and gender in a sample balanced across gender and age, only one region differed between groups. Deactivation was present in the precuneus for the MDD group, with minimal differential use of this region for the HC group. The precuneus is part of the task-positive network (43). Emotional salience may interfere with the ability to engage the task-positive network in those with MDD, resulting in disengagement of this region during emotion processing. The disengagement of the lateral precuneus and potentially other parts of this network during emotion processing might explain why performance is typically diminished in MDD.

Given the multiple interactions between gender, age, and MDD status, the lack of robust differences between the undifferentiated MDD and HC samples is not surprising. The critical implication of this finding is that evaluation of brain activation during emotion processing without accounting for and investigating separately the effects of age and gender may mask important network dysfunction pertinent to emotion processes in MDD. The inclusion of disproportionally few men and older adults in studies of emotion processing in MDD could be responsible for some proportion of the variability in prior literature. In addition, MDD is a heterogeneous illness. Disease severity, psychiatric comorbidities, medication status, and other clinical factors are potential complicating characteristics in interpreting findings within and across studies. Gender and age must also be seriously considered, and may be factors in the heterogeneity of findings with regard to the pathophysiology of MDD.

Limitations

Although the present sample size was substantially larger than is typical of neuroimaging studies, the number of participants within each cell was modest. These modest cell sizes reflect the challenge in conducting investigations of age and gender effects in MDD, as testing for these effects require large sample sizes. Replicating these findings with a larger sample would provide additional power to pursue more nuanced inquiry within this area. This MDD sample was composed of individuals with varied disease severity, illness chronicity, medication status and psychiatric and medical comorbidities. Although this is a limitation with regard to sample homogeneity, this heterogeneity reflects the typical MDD expression within the population. There were very small cells for linear analyses of correlations between these characteristics, in addition to performance, and the regions of interest, and these results are not reported due to highly variable estimates of effect sizes. Future, larger, or more targeted studies will be needed to examine the potential role of these characteristics in the observed interactions. Our study also did not allow for hypothesis testing regarding the relative contributions of biological, learning/socialization, or interactive factors to the observed gender differences. For example, information regarding phase of menstrual cycle in women was not collected, which has been shown to influence emotion processing circuitry (44).

Conclusions and implications

This study has critical implications for future research in the neurobiology of MDD. Gender and age must be carefully evaluated when conducting these studies through either balancing and evaluating gender and age effects within samples, or utilizing more homogenous samples. Research should also be directed towards better understanding the neurobiological mechanisms underlying gender- and age- specific activation differences in MDD. This research will provide enhanced understanding of the heterogeneity of MDD and better targeting of individualized treatments for depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: Wayne State University Thesis/Dissertation Research Support (EMB); National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD; SAL); K-23 Career Development Award (MH074459, SAL); University of Michigan Department of Psychiatry Research Committee (SAL); University of Michigan Depression Center (SLW, SAL); University of Michigan fMRI Lab Pilot Scans (SAL, SLW); University of Michigan Claude D. Pepper Center (SLW); Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (SAL, SLW); MICHR Pilot Grant Fund (SLW); Rachel Upjohn Clinical Scholars Award (SAL, SLW); Phil F. Jenkins Research Fund (JKZ)

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Erich Avery and Brennan Haase for their assistance in data collection and processing. Funding for the present study included the following: Wayne State University Thesis/Dissertation Research Support (EMB); National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD, SAL); K-23 Career Development Award (SAL); University of Michigan Department of Psychiatry Research Committee (SAL); University of Michigan Depression Center (SLW, SAL); University of Michigan fMRI Lab Pilot Scans (SAL, SLW); University of Michigan Claude D. Pepper Center (SLW); Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (SAL, SLW); MICHR Pilot Grant Fund (SLW); Rachel Upjohn Clinical Scholars Award (SAL, SLW); Phil F. Jenkins Research Fund (JKZ).

Footnotes

Preliminary results of this work were presented at the 41st Annual Meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society, Waikoloa, HI, February 6–9, 2013

The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

All participants completed informed consent procedures per institutional review board guidelines.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Csukly G, Czobor P, Szily E, et al. Facial expression recognition in depressed subjects: The impact of intensity level and arousal dimension. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2009;197:98–103. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181923f82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briceño EM, Weisenbach SL, Rapport LJ, et al. Shifted inferior frontal laterality in women with major depressive disorder is related to emotion-processing deficits. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:1433–1445. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surguladze S, Brammer MJ, Keedwell P, et al. A differential pattern of neural response toward sad versus happy facial expressions in major depressive disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence NS, Williams AM, Surguladze S, et al. Subcortical and ventral prefrontal cortical neural responses to facial expressions distinguish patients with bipolar disorder and major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55:578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright SL, Langenecker SA, Deldin PJ, et al. Gender-specific disruptions in emotion processing in younger adults with depression. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:182–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thayer JF, Johnsen BH. Gender differences in judgement of facial affect: A multivariate analysis of recognition errors. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2000;41:243–246. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wager TD, Phan KL, Liberzon I, et al. Valence, gender, and lateralization of functional brain anatomy in emotion: a meta-analysis of findings from neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 2003;19:513–531. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weisenbach SL, Rapport LJ, Briceño EM, et al. Reduced emotion processing efficiency in healthy men relative to women. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2014;9:316–325. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calder AJ, Keane J, Manly T, et al. Facial expression recognition across the adult life span. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:195–202. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan S, Ruffman T. Emotion recognition deficits in the elderly. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;114:403–432. doi: 10.1080/00207450490270901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer H, Sandblom J, Gavazzeni J, et al. Age-differential patterns of brain activation during perception of angry faces. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;386:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunning-Dixon FM, Gur RC, Perkins AC, et al. Age-related differences in brain activation during emotional face processing. Neurobiology of Aging. 2003;24:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brassen S, Kalisch R, Weber-Fahr W, et al. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex processing during emotional evaluation in late-onset depression: A longitudinal fMRI-study. International Journal of Psychology. 2008;43:265–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aizenstein HJ, Andreescu C, Edelman KL, et al. fMRI correlates of white matter hyperintensities in late-life depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:1075–1082. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10060853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright SL, Langenecker SA. Differential risk for emotion processing difficulties by gender and age in Major Depresive Disorder. In: Hernandez P, Alonso S, editors. Women and Depression. Chapter 3. Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2009. pp. 183–216. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavretsky H, Lesser IM, Wohl M, et al. Relationship of age, age of onset, and sex to depression in older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1998;6:248–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavretsky H, Kurbanyan K, Ballmaier M, et al. Sex differences in brain structure in geriatric depression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;12:653–657. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.6.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langenecker SA, Bieliauskas LA, Rapport LJ, et al. Face emotion perception and executive functioning deficits in depression. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2005;27:320–333. doi: 10.1080/13803390490490515720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rapport LJ, Friedman SL, Tzelepis A, et al. Experienced emotion and affect recognition in adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology. 2002;16:102–110. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.16.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langenecker SA, Weisenbach SL, Giordani B, et al. Impact of chronic hypercortisolemia on affective processing. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward BD. Simultaneous inference for fMRI data. Analysis of Functional Images (AFNI) Documentation. 2000 http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/pub/dist/doc/manual/AlphaSim.pdf.

- 25.Fusar-Poli P, Placentino A, Carletti F, et al. Laterality effect on emotional faces processing: ALE meta-analysis of evidence. Neuroscience Letters. 2009;452:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielson KA, Langenecker SA, Garavan H. Differences in the functional neuroanatomy of inhibitory control across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:56–71. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Payer DE, Baicy K, Lieberman MD, et al. Overlapping neural substrates between intentional and incidental down-regulation of negative emotions. Emotion. 2012;12:229–235. doi: 10.1037/a0027421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fusar-Poli P, Placentino A, Carletti F, et al. Functional atlas of emotional faces processing: a voxel-based meta-analysis of 105 functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2009;34:418–432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mak AKY, Hu Z-g, Zhang JX, et al. Neural correlates of regulation of positive and negative emotions: An fMRI study. Neuroscience Letters. 2009;457:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rypma B, D’Esposito M. The roles of prefrontal brain regions in components of working memory: Effects of memory load and individual differences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:6558–6563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas EJ, Elliott R, McKie S, et al. Interaction between a history of depression and rumination on neural response to emotional faces. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1845–1855. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hampel P, Petermann F. Perceived stress, coping, and adjustment in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tompkins TL, Hockett AR, Abraibesh N, et al. A closer look at co-rumination: Gender, coping, peer functioning and internalizing/externalizing problems. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:801–811. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Honkalampi K, Saarinen P, Hintikka J, et al. Factors associated with alexithymia in patients suffering from depression. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 1999;68:270–275. doi: 10.1159/000012343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee B-T, Lee H-Y, Park S-A, et al. Neural Substrates of Affective Face Recognition in Alexithymia: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Neuropsychobiology. 2011;63:119–124. doi: 10.1159/000318086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheibe S, Carstensen LL. Emotional aging: Recent findings and future trends. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2010;65:135–144. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams LM, Brown KJ, Palmer D, et al. The mellow years? : Neural basis of improving emotional stability over age. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:6422–6430. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0022-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smoski MJ, LaBar KS, Steffens DC. Relative effectiveness of reappraisal and distraction in regulating emotion in late-life depression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.070. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Aldao A. Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;51:704–708. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binder J, de Quervain DJF, Friese M, et al. Emotion suppression reduces hippocampal activity during successful memory encoding. Neuroimage. 2012;63:525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waring JD, Etkin A, Hallmayer JF, et al. Connectivity underlying emotion conflict regulation in older adults with 5-HTTLPR short allele: A preliminary investigation. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.08.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cavanna AE, Trimble MR. The precuneus: a review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain. 2006;129:564–583. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guapo VG, Graeff FG, Zani ACT, et al. Effects of sex hormone levels and phases of the menstrual cycle in the processing of emotional faces. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1087–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.