Abstract

Context

The Palliative Care Research Cooperative group (PCRC) is the first clinical trials cooperative for palliative care in the United States.

Objectives

To describe barriers and strategies for recruitment during the inaugural PCRC clinical trial.

Methods

The parent study was a multi-site randomized controlled trial enrolling adults with life expectancy anticipated to be 1–6 months, randomized to discontinue statins (intervention) vs. to continue on statins (control). To study recruitment best practices, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 18 site Principal Investigators (PI) and Clinical Research Coordinators (CRC), and reviewed recruitment rates. Interviews covered 3 topics – 1) successful strategies for recruitment, 2) barriers to recruitment, and 3) optimal roles of the PI and CRC.

Results

All eligible site PIs and CRCs completed interviews and provided data on statin protocol recruitment. The parent study completed recruitment of n=381 patients. Site enrollment ranged from 1–109 participants, with an average of 25 enrolled per site. Five major barriers included difficulty locating eligible patients, severity of illness, family and provider protectiveness, seeking patients in multiple settings, and lack of resources for recruitment activities. Five effective recruitment strategies included systematic screening of patient lists, thoughtful messaging to make research relevant, flexible protocols to accommodate patients’ needs, support from clinical champions, and the additional resources of a trials cooperative group.

Conclusion

The recruitment experience from the multi-site PCRC yields new insights into methods for effective recruitment to palliative care clinical trials. These results will inform training materials for the PCRC and may assist other investigators in the field.

Keywords: palliative care, recruitment, research networks, clinical trials

INTRODUCTION

Research is necessary to guide high quality palliative care and the selection of treatments to maximize health outcomes for these patients and their families. Palliative care research encompasses patients with diverse diagnoses, all with serious and incurable illnesses which are potentially life-limiting. In the period of illness leading up to death, treatments must be chosen with parsimony, maximizing benefit while avoiding harms. Studies relevant to hospice and palliative care comprise <1% of clinical trials, and seriously ill patients are systematically excluded from other research.1 Few investigators have the practical and methodological expertise to conduct these studies, making it critical to disseminate successful research strategies.2,3

Palliative care clinical trials must enroll sufficient numbers of patients for scientific validity, yet participation is not easy for this population.4 Recruitment is a major challenge – 80% of palliative care investigators awarded funding from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research reported recruitment barriers, and participation rates of 50% or less are common.32,5

Barriers to recruitment to palliative care trials are ethical and practical in nature. Patients and families become physically and emotionally vulnerable in the face of serious illness, adding potential burden, or even risk, to research. Practical concerns include communication barriers such as expressive aphasia or delirium, or limited mobility or energy.6 Ethical concerns – which may influence approval by Institutional Review Boards, include patient vulnerability, high rates of cognitive impairment and emotional distress challenging true informed consent, clinician-researcher role conflicts, and research burden.7,8

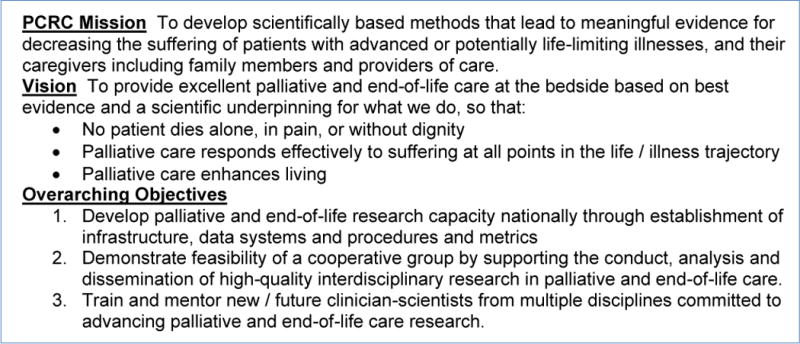

Clinical trial networks are one mechanism to pool expertise and enhance research productivity and quality.9 The first Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group (PCRC) in the United States was initiated in 2010 with foundational funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research that started in January 2011 (NINR; UC4NR012584). The PCRC’s overarching mission is to develop scientific methods that lead to meaningful evidence for decreasing the suffering of patients with advanced or potentially life-limiting illnesses, and their caregivers. Specific objectives include expanding research capacity, conducting high impact clinical trials, and training new investigators. (Figure) The conduct of the PCRC’s inaugural multi-site clinical trial provided a unique opportunity to examine effective strategies for enrolling seriously ill patients. We interviewed investigators and research coordinators from 9 participating PCRC sites in order to describe barriers and strategies for recruitment to palliative care clinical trials.

Figure.

Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group (PCRC)

METHODS

To understand best practices for recruitment to palliative care clinical trials, we interviewed key research personnel from PCRC sites. Data collection consisted of semi-structured interviews with each site Principal Investigator (PI) and Clinical Research Coordinator (CRC) for PCRC member sites, and review of site-specific recruitment rates.

Rationale and Design of the Inaugural PCRC Clinical Trial

The PCRC is a clinical trials cooperative group composed of investigators with a shared vision that excellent palliative care at the bedside is contingent on best evidence and a scientific underpinning for clinical care.10 At the time of this investigation, all sites were active participants in the PCRC’s inaugural clinical trial: “A multisite randomized controlled trial of continuing vs. discontinuing statins in palliative care patients with limited prognosis.” Statins reduce risk of future cardiovascular events for patients with hyperlipidemia.11 Studies demonstrate lesser or no cardiovascular risk benefits in populations with severe co-morbid illnesses.12,13,14,15 Statins are frequently continued in serious or life-limiting illness, in the absence of evidence for safe discontinuation.16,17,18,19 Observational studies provide varied evidence for the safety of statin discontinuation.20,21 The risks vs. benefits of statins for palliative care patients remains an area of compelling clinical uncertainty.

The parent study was a non-blinded multi-site randomized controlled trial enrolling adults with limited life expectancy anticipated to be 1–6 months, on statins for primary or secondary prevention. Persons with cardiovascular events in the preceding 6 months were excluded, as were those whose primary physicians found contraindications to safe enrollment. Participants were randomized 1:1 to discontinue statins (intervention) vs. to continue statins (control), stratified by site and cardiovascular history. Enrolled patients were followed for up to 1 year with interviews and medical record reviews. The primary outcome was 60-day survival; secondary outcomes included cardiovascular events, symptoms, health related quality of life, polypharmacy, costs, and patient satisfaction with care. A standard research protocol was followed at all sites; site-specific IRB review was required and recruitment methods had to meet these human subjects standards.

Methods for Semi-structured Recruitment Interviews

Each of the 18 site PIs and CRCs at the 9 active enrollment sites were eligible for interviews, which were conducted as recruitment for the statin trial ended. The interview script was semi-structured to participants to explain stated barriers or strategies. Interview items were developed for the unique objectives of this study, and covered 3 topics – 1) successful strategies used for recruitment to the statin protocol and other palliative care research, 2) barriers to recruitment, and 3) optimal roles of the PI and CRC in recruitment for palliative care research. Participants described their experience and current level of involvement in palliative care research. Site PIs were interviewed by the investigators (JB, LCH), and site CRCs were interviewed by participating CRCs (LM, KW). All interviews were conducted by telephone, using the interview script with probes to explore individuals’ answers to each question. All sites also provided data on actual recruitment of research subjects for the statin discontinuation clinical trial. Participants gave verbal informed consent; the study was judged exempt from review by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

All interviews were recorded and professionally transcribed. Investigators used directed content analysis for theme identification, using the concepts of process barriers and facilitators and relevant research to guide initial codes.22,23 Investigators (LCH, JB, KW, LM, REB) independently sought themes in a subset of the transcripts, and initial themes were pooled and discussed until consensus was reached. Each participant was identified by role (PI or CRC) and by whether their site had recruited higher or lower than the average number of participants for all sites. Thematic grouping were examined for content on barriers and successful strategies, and representative quotes were selected.

RESULTS

All 18 eligible site PIs and CRCs completed interviews. In addition to palliative care, investigators’ specialties included geriatric medicine, general medicine and medical oncology. All site PIs and nearly all CRCs had prior research experience with seriously ill patients. Site PIs reported prior experience with between 2 and “more than 60” clinical trials. Investigators estimated spending 10–30% of their time on the statin protocol. All CRCs had prior experience conducting research with chronically or seriously ill patients, yet several were new to clinical trials. They reported spending 50–100% of their time on the statin protocol during active recruitment. The study protocol completed recruitment of n=381 patients on April 30, 3013. Site enrollment ranged from 1–109 participants, with an average of 25 enrolled per site.

Barriers

PIs and CRCs described five major barriers to palliative care research recruitment: difficulty finding eligible patients, patient illness, physician or caregiver protectiveness, demands of multiple settings, and scarce resources. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Themes and Example Quotations for Palliative Care Recruitment Barriers

| Themes | Examples |

|---|---|

| Barrier: Finding eligible patients | “Even though I have screened so many thousands of charts, there just aren’t people who meet our specifications so that has been a huge challenge ….” –high/CRC “It is hard to screen on prognosis. It is also hard to know what their performance status is.” –low/PI “It is really difficult identifying people who are eligible … they have already gone home, and then it turns into essentially a cold call and really they are not as receptive to a phone call as they would be an in person visit.” –high/CRC “There are few oncologists that think their patients are always going to live forever.…” –high/PI |

| Barrier: Patient illness | “Most of them will tell me, okay can you come back because I am not doing too well now, and I tell them okay I will come back and then when I go back, they would ask me to come back again; I am still unwell.” –low/CRC “I think the biggest barrier is these people are sick, they are in the hospital not because they wanted to come in, they do not feel good, and a lot of times I think patients just simply did not feel good, they did not want to talk, they were tired.” –high/CRC |

| Barrier: Physician / caregiver protectiveness | “This is a vulnerable population, and often times you do not just interact with the patient, you interact with the family, the providers who may, you know, have an emotional attachment to the patient.” –high/CRC “I went to each research group and they were all willing to put patients on but when it comes down to that day in their clinic, it is very hard for them to be able to do that because they feel like they are always giving patient bad news; so if the patients are getting bad news, I do not even get a chance to get into the door.” –low/CRC “Hospice nurses actually can be a barrier and I think the biggest reason is they feel on some level it is intrusive to a patient or that it is going to take too much time and the patient is already vulnerable or in a weakened state … some that tend to say ‘oh no my patients cannot do it right now, they are declining too fast.’” –high/PI “… on reasons for refusal, one reason seems to be when the patient’s family members have concerns about patient’s participation in the study” –low/CRC “We have had a few primary care physicians who have said that their patients are too sick to participate, I mean too burdened by illness to participate.” –high/PI |

| Barrier: Demands of multiple settings | “I think we have been most successful in sites where there is a committed investigator doing enough hands on clinical stuff so they have access to the patients themselves. We have been less successful in settings where we are fully dependent on CRC contacting the primary physician” –high/PI “It is very hard to see someone in clinic. The waiting room is not a good area and if they get in the back … you do not want to disrupt their clinic flow and then when they are done, they are done, they want to go home.” –high/PI “We found that our poor CRC was spending so much time sitting in this clinic, sitting in that clinic, … This is where we sat down after I think was probably a couple of months, I said okay … are we demonstrating that we are getting return on investment, … and the places where it was not, we just pulled out.” –high/PI |

| Barrier: Resources | “I feel like I do not have a lot support on the ground level.” –high/CRC “We need more staff.” –High, PI “We need to be able to get paid even when we have an off month recruiting because things do ebb and flow and that is very problematic for us.” –High, PI “Underwriting the clinical research nurse … In order to get out there and start doing this it can’t just be recruitment dependent in the early stages” – Low, PI “I really think that there could have been a little more planning done to aid in the beginning recruitment process for the initial sites.” –high/CRC |

First, they reported difficulty finding patients who meet the prognosis required for a palliative care trial. Patients frequently must meet prognostic criteria which are not routinely recorded in the medical record. CRCs compared screening hundreds or even thousands of medical records each week to searching for a “needle in a haystack.” By the time a patient was identified and approached, they might have become more ill or changed settings; as one CRC noted when finding patients from the hospital census, “It is really difficult identifying people who are eligible … they have already gone home, and then it turns into essentially a cold call.” Information on disease stage, functional status or anticipated life expectancy is recorded inconsistently, and is usually found in text notes rather than electronic records. Physicians tend to overestimate their own patients’ prognosis, which may contribute to lack of documentation.

The second and third themes identified barriers that were often conceptually linked. Patient illness severity resulted in symptoms that limited research participation. (Table 1) Patients who were in pain, had severe fatigue or nausea, simply felt overwhelmed by the demands of serious illness. Investigators or CRCs often discussed severity of illness and then linked it to the third theme of physician or caregiver protectiveness. Researchers approached family or nurses to learn if patients were able to discuss participation – and found these individuals were protective to the point of refusal on the patient’s behalf. Investigators and CRCs reported experiences with clinic physicians, hospice nurses and primary care doctors who would not permit recruiting visits, because they believed patients would be overly burdened by research participation.

A fourth theme was the logistic demands created by seeking patients who were in multiple healthcare settings. (Table 1) Patients with serious illness see multiple providers and frequently transfer from outpatient to inpatient or long-term care settings.24 Staff and investigators reported they had to establish recruitment procedures in many, rather than one clinical site, and each demanded additional time.

Finally, investigators discussed lack of resources, particularly personnel time, as an important fifth barrier to recruiting. They indicated that palliative care research required greater investments in personnel time than non-palliative care clinical trials. Participants also noted the need for systematic preparation and training of personnel to approach palliative care patients and families.

Effective Strategies for Recruitment

Participating site PIs and CRCs reported numerous strategies they found to be effective to recruit palliative care patients to the statin protocol, and to other studies. Themes for effective recruitment included effective screening, messaging, flexibility, clinical champions, and the benefits of the cooperative group.

Investigators used efficient approaches to screen large patient populations to find the small subset who met palliative care trial eligibility. Screening procedures typically involved daily review of hospital census or clinic schedules. (Table 2) While the need for screening techniques was universal, the approaches depended on site-specific knowledge. Hospice providers added a screening admission question to identify patients on statins, while one site with an electronic clinical database paid for a systematic monthly query to find potentially eligible patients with scheduled clinic visits.

Table 2.

Themes and Example Quotations for Palliative Care Recruitment Strategies

| Themes | Examples |

|---|---|

| Strategy: Effective Screening | “We have phenomenal electronic medical record system and each day I can go in and review every patient in the hospital who is under the medical service and the palliative care service and I simply click on the med list, find any patient who is on statins, find who their attending physician is, contact them, ask if they would be okay with me contacting their patient to discuss the study.” –high/CRC “If somebody is on a statin then we have added a question to our electronic health records for the admissions nurse to ask if they would be willing to be contacted by the research department for a study about their statin.” –high/PI “On the front end side of things when we are identifying where we are going to be recruiting from and the processes for recruiting from each site that I have as the PI had a lot of involvement with making the outreach to my colleagues to gain entry with the CRC.” –high/PI “What we have done to at least help identify participants is to use our electronic database house to help us screen people that meet criteria the way it is set. So we query the database twice a week as that helps identify people on that screen per our eligibility criteria.” –low/PI |

| Strategy: Messaging | “I talk about the study in general, but then when talking about research, a lot of people really are at crossroads in their disease process … and being able to give back and help someone else is sometimes a good incentive for participation.” –high/CRC “I do emphasize that it is research because it has benefits and risks but again I am not using them as a guinea pig because they are not, it is volunteer. I express appreciation for them every single time. Every time I talk to them on the phone, I make sure that they know that I am appreciative that they took their time off to talk to me, and I thank them at the end of every call, you know to remind them that information that we received is helpful not only for them but for somebody down the road.” –high/CRC “Usually when I am first meeting them, I reach out and shake their hand, I hold their hand, I am up close and personal with them, get a chair and sit down and start going through the study.” –high/CRC “I think it is important to talk at a level that is understandable for everybody, so not using a lot of jargon and speaking in a way that anybody could understand, that they do not need to be a health professional to understand what I am trying to say.” –high/CRC |

| Strategy: Flexibility | “I let them know that if they are too tired to talk to me or if there is too much going on, I can also talk with anybody else that they designate … and so there are lots of different options, … so I think that is comforting to them, … even though they have a lot going on, there is a way that they can provide information that might help somebody else.” -high/CRC “I get at least 50%, maybe more, of all the people I enroll in the study by going to their home. They are comfortable in their own space. I can sit down with them at the table and discuss the study in conversational terms.” –high/CRC “I think that being flexible and sometimes it may take several tries or extended over a couple of different visits to get all the information. It may be somebody needs to first hear about the study and then think about it and then come back. Not thinking that you can just walk in and get this done in half an hour.” –high/PI |

| Strategy: Clinical Champions | “We try to get them (providers) excited about the study, we try to get them excited about helping with a relationship, … so this is just one more aspect of another person checking up on their patient and potentially sharing information that is good for them, so we try to make the providers excited too, and that has been beneficial.” -high/CRC “What I found to be most useful for each clinical area is to start by figuring out who the key people are and talking to them first, either one on one or small groups about the study, what does it mean, why are we doing it and get their input into how do we then either access the population or introduce it to the other clinicians.” –high/PI “I try to take time out to ask how they are doing and listen to what they say, … I try to make sure that they know how appreciative I am of that relationship because they are busy, they are seeing lots of patients and they have much more direct patient contact than I do, so they are having to deal with the heartache of somebody who is going through a medical crisis or pain crisis or psychosocial crisis … when they refer a patient, I make sure that I say ‘we appreciate your referral so much. Thank you for thinking of us’.” –high/CRC “It is important for not only PIs but other providers to be engaged and have some sort of involvement with the study. An example is outside hospices or inpatient units. … we have had the most success in areas where the providers, nursing staff are actually kind of excited about us seeing their patients.” –high/CRC “Identifying a champion is essential to address barriers that you meet with recruitment, educating the staff person who works within the palliative care system and first contacts patients for the study.” –low/CRC |

| Strategy: Cooperative Group Resources | “I think the teleconferences have been a great asset so that coordinators of each site know some working strategies and some of them are able to identify some nuances at other sites that you may be facing. I think the telephone conferences are major plus.” –low/CRC “I think having support from your other team members is extremely helpful and honestly if you have that that would improve recruitment and all of the above.” –high/CRC “Monthly research meetings of the investigators are really important. I think it has to be mandatory, because working with a lot of sites some of them do research, some of them do not, but you do not know how essential that is until you have tried to work without it.” –high/PI |

Palliative care researchers described careful messaging as a second critical recruitment strategy. Messaging about palliative care generally, and about a specific study protocol, was reported as essential to engage patients. They described the importance of content, including explanation of the meaningfulness of research and the concept of leaving a legacy by helping others with similar illness. CRCs were careful to include expressions of gratitude for patients’ willingness to help and share their time or opinions. (Table 2) In addition to careful content, communication style and interpersonal approach was considered equally important. CRCs emphasized having empathy, favoring in person rather than telephone approaches, use of simple and clear language to explain the study and sensitivity to body language.

Respondents also discussed the critical strategy of flexibility in recruitment. As the sample quotes in Table 2 illustrate, CRCs and PIs describe a multitude of ways to accommodate the needs of palliative care patients and caregivers. They designed protocols to permit greater time flexibility, and to permit the patients to control timing of study visits. In many examples, patients were allowed to control the location of interviews as well – in hospital rooms, clinics, or even in their own homes – to ensure comfort and convenience. In some examples, flexibility also meant allowing family surrogates to speak on the patient’s behalf, as one CRC noted “I let them know that if they are too tired to talk to me or if there is too much going on, I can also talk with anybody else that they designate … and so there are lots of different options.” This theme illustrated creative approaches used to reduce the burden of trial participation for palliative care patients, therefore making recruitment more feasible.

Another recruitment strategy was engagement of clinical champions who assisted with access to patient populations. Interview participants noted this as an essential role for a PI, who would cultivate relationships with clinical leaders and build enthusiasm for the trial. (Table 2) Champions were defined by their ability to give entrée to patients, but also by their willingness to introduce the trial to patients or make referrals. Typically this role began with the champion’s scientific interest in the study, but sometimes included incentives such as in-service education, small gifts of food, or (rarely) payments for each successful patient referral.

Finally, some interview participants noted ways that the PCRC, as a research cooperative, was a resource to improve clinical trials recruitment. (Table 2) Comments focused on team-based support, sharing and disseminated best practices in an on-going clinical trial, and learning together from successes.

Role of the PCRC to Enhance Recruitment

To wrap up each interview, respondents were asked if there was any systematic ways the Palliative Care Research Cooperative group could improve recruitment. Respondents’ suggestions included training for research staff and support for the role of site principal investigator. Suggestions for training research staff included sharing effective recruitment methods systematically, and rapid dissemination of new research protocols including specifics of recruitment. Respondents recommended that the PCRC promote and reward engagement by principal investigators, including participation in regular teleconferences, shared methods to introduce palliative care concepts, and direct involvement in recruitment.

DISCUSSION

This study draws on the recruitment experience from the multi-site PCRC to gain new insights into methods for effective recruitment to palliative care clinical trials. This study compiles perspectives from experienced investigators and research staff on best practices to support recruitment of patients with life-limiting illness for research. To achieve this goal respondents reported use of screening strategies to find eligible patients, thoughtful messaging when approaching potential participants, built flexibility into protocols to facilitate participation, and cultivated relationships with clinical champions who endorsed the value of this research. Dissemination of these recruitment strategies can encourage future palliative care clinical trials.

This study adds to a small but critical body of empiric evidence for best practices in palliative care research methods. In a meta-synthesis of palliative care interventions, Evans found that poor recruitment and sample size insufficient to detect change was one of four common methodologic weaknesses in this body of research.25 Successful strategies highlighted in this review included 1) active and systematic screening for eligibility, 2) anticipating the gatekeeping concerns of family caregivers and clinicians, and 3) strategies to facilitate patient or caregiver participation, such as anticipating fatigue or burden. Indeed, successful recruitment programs can be instituted. Riopelle and colleagues completed a successful palliative care intervention study enrolling 400 (70%) of 561 eligible patients with advanced life-limiting illness.26 These investigators attributed effective recruitment to 1) purposeful case-finding through physician prognostication, 2) interviewer training and support, 3) systematic and flexible strategies to minimize patient or caregiver burden, and 4) consistent interviewer-respondent assignment. Similarly, LeBlanc and colleagues described the successful accrual of 461 (76%) of 607 eligible patients in 26 months using a recruitment algorithm including, 1) systematic triage, 2) information booklets for stakeholders, 3) trained recruitment personnel, and 4) standardized wording in all communications.27 This approach was replicated in another palliative care study with similar outcomes.28 Investigators acknowledge the importance of clinical trial recruitment methods, in the wake of concerns regarding poor accrual to protocols.29,30,31 The National Institutes of Health acknowledges recruitment as a major threat to science benefitting seriously ill patients, and the National Cancer Institute disseminates best practices in cancer clinical trials recruitment through its AccrualNet website.32,33

Our study should be interpreted with certain considerations in mind. Participants are among the most experienced palliative care investigators in the United States, yet may not represent the views of investigators with similar experience outside the PCRC. Recruitment approaches varied by site, since site-specific IRB requirements applied and site investigators recruited in diverse settings and populations. All participants were actively recruiting for a single protocol, and particular demands of this protocol and the early experience of a cooperative group may skew their responses. We did not study methods of retention, a related methods concern for palliative care research.

Our findings have important implications for the design and funding of future palliative care clinical trials. First, study protocols have to be written with some latitude in recruitment procedures, to accommodate the needs of this vulnerable patient population. Flexibility in timing, site and pacing of research is necessary to facilitate participation while mitigating burdens. Second, research budgets should be adapted to ensure adequate personnel time – from investigators and research staff – to be dedicated to recruitment activities such as identifying champions, screening large patient populations, and approaching patients and families in a manner respectful of their needs. Third, investigators should anticipate the need to train themselves and their research staff on effective recruitment strategies.

The results of this study will be used within the PCRC to develop standardized training materials for palliative care recruitment methods. Given the paucity of experienced palliative care investigators and staff, it may be more effective to provide training in research methods using a centralized repository of materials. Future trials within the PCRC will emphasize engagement with junior investigators and dissemination of effective methods to member investigators. This repertoire of training tools in palliative care methods, including approaches to enhance recruitment, will be accessible and serve as a resource to the larger field of palliative care research.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: NIH-National Institute for Nursing Research UC4 NR012584

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES AND CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS:

Dr. Hanson has research funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Funds are distributed to the University of North Carolina for salary and research support. Further consulting is pending for the Research Triangle Institute.

Dr. Abernethy has research funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Cancer Institute, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, DARA, Glaxo Smith Kline, Celgene, Helsinn, Dendreon and Pfizer; these funds are all distributed to Duke University Medical Center to support research including salary support for Dr. Abernethy. Pending industry funded projects include: Genentech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Insys, and Kanglaite. In the last 2 years she has had nominal consulting agreements with or received honoraria from (<$10,000 annually) Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Further consulting with Bristol Meyers Squibb is pending in 2013, for role as Co-Chair of a Scientific Advisory Committee. Dr. Abernethy has a paid leadership role with American Academy of Hospice & Palliative Medicine (President). She has corporate leadership responsibility in AthenaHealth (health IT company), Advoset (an education company that has a contract with Novartis), and Orange Leaf Associates LLC (an IT development company).

Dr. Kutner has research funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Cancer Institute, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. She is supported by the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation (IMDF) in her role as Medical Editor. All of these funds are all distributed to University of Colorado School of Medicine to support research including salary support for Dr. Kutner.

References

- 1.Tieman J, Sladek R, Currow D. Changes in the quantity and level of evidence of palliative and hospice care literature: the last century. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5679–5683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.6230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibbins J, Reed CM, Bloor S, Burcombe M, McCoubrie R, Forbes K. Overcoming barriers to recruitment in care of the dying research in hospitals. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.04.005. e-publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keeley PW. Improving the evidence base in palliative medicine: a moral imperative. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:757–760. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.022632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storey CP. Trying trials. J Pall Med. 2004;7:393–394. doi: 10.1089/1096621041349455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinck GC, van den Bos GA, Kleijnen J, de Haes HJ, Schade E, Veenhof CH. Methodologic issues in effectiveness research on palliative cancer care: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1697–1707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanratty B, Lowson E, Holmes L, Addington-Hall J, Arthur A, Grande G, Payne S, Seymour J. A comparison of strategies to recruit older patients and carers to end-of-life research in primary care. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:342. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hickman SE, Cartwright JC, Nelson CA, Knafl K. Compassion and vigilance: investigators’ strategies to manage ethical concerns in palliative and end-of-life care. J Pall Med. 2012;15:880–889. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casarett DJ, Karlawish JHT. Are special ethical guidelines needed for palliative care research? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:130–139. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abernethy AP, Hanson LC, Main Ds, Kutner JS. Palliative care clinical research networks a requirement for evidence-based palliative care: time for coordinated action. J Pall Med. 2007;10:845–850. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leblanc TW, Kutner JS, Ko D, Wheeler JL, Bull J, Abernethy AP. Developing the evidence base for palliative care: formation of the palliative care research cooperative and its first trial. Hosp Pract. 2010;38:137–142. doi: 10.3810/hp.2010.06.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Lloyd-Jones DM, Blum CB, McBride P, Eckel RH, Schwartz JS, Goldberg AC, Shero ST, Gordon D, Smith SC, Jr, Levy D, Watson K, Wilson PW. ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in AdultsA Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Nov 7; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. doi S0735-1097(13)06028-2. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Currow DC, Stevenson JP, Abernethy AP, Plummer J, Shelby-James TM. Prescribing in palliative care as death approaches. J Am Ger Soc. 2007;55(4):590–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang S, Shang L, Sun A, Jiang H, Qian J, Ge J. Efficacy of statin therapy in chronic systolic cardiac insufficiency: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2011;22:478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer SC, Craig JC, Navaneethan SD, Tonelli M, Pellegrini F, Strippoli GFM. Benefits and harms of statin therapy for persons with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:263–275. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vollrath AM, Sinclair C, Hallenbeck J. Discontinuing cardiovascular medications at the end of life: lipid-lowering agents. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:876–881. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silveira MJ, Kazanis AS, Shevrin MP. Statins in the last six months of life: a recognizable, life-limiting condition does not decrease their use. J Pall Med. 2008;11(5):685–693. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vollrath AM, Sinclair C, Hallenbeck J. Discontinuing cardiovascular medications at the end of life: lipid-lowering agents. J Pall Med. 2005;8(4):876–881. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bayliss EA, Bronsert MR, Reifler LM, Ellis JL, Steiner JF, McQuillen DB, Fairclough DL. Statin prescribing patterns in a cohort of cancer patients with poor prognosis. J Pall Med. 2013;16:412–418. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silveira MJ, Kazanis AS, Shevrin MP. Statins in the last six months of life: a recognizable, life-limiting condition does not decrease their use. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:685–693. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell CM, Strener SS, Gunraj N, Huo C, Bierman AS, Scales DC, Bajcar J, Zwarenstein M, Urbach DR. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2011;306:840–847. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1648–1654. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glaser M, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pham HH, Schrag D, O’Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1130–1139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans CJ, Harding R, Higginson IJ, on behalf of MORECare ‘Best practice’ in developing and evaluating palliative and end-of-life care services: a meta-synthesis of research methods for the MORECare project. Palliative Med. 2013;27:885–898. doi: 10.1177/0269216312467489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riopelle D, Wagner GJ, Steckart J, Lorenz KA, Rosenfeld KE. Evaluating a palliative care intervention for veterans: challenges and lessons learned in a longitudinal study of patients with serious illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:1003–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leblanc TW, Lodato JE, Currow DC, Abernethy AP. Overcoming recruitment challenges in palliative care clinical trials. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(6):277–282. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Wurzelmann J, Janning SW, Bull J, Norris JF, Baringtang DC, Pierce A, Snidow J. Enhancing enrollment in palliative care trials: key insights from a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Support Oncol. 2010;8(3):139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agrawal M, Danis M. End-of-life care for terminally ill participants in clinical research. J Pall Med. 2002;5:729–737. doi: 10.1089/109662102320880552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapo J, Casarett D. Working to improve palliative care trials. J Pall Med. 2004;7:395–397. doi: 10.1089/1096621041349400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penrod JD, Morrison RS. Challenges for palliative care research. J Pall Med. 2004;7:398–402. doi: 10.1089/1096621041349392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Mara AM, St Germain D, Ferrell B, Bornemann T. Challenges to and lessons learned from conducting palliative care research. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AccrualNet, National Cancer Institute. https://accrualnet.cancer.gov/ Accessed December 20, 2013.