Abstract

Arsenic is enriched up to 28 times the average crustal abundance of 4.8 mg kg−1 for meta-sedimentary rocks of two adjacent formations in central Maine, USA where groundwater in the bedrock aquifer frequently contains elevated As levels. The Waterville Formation contains higher arsenic concentrations (mean As 32.9 mg kg−1, median 12.1 mg kg−1, n=36) than the neighboring Vassalboro Group (mean As 19.1 mg kg−1, median 6.0 mg kg−1, n=36). The Waterville Formation is a pelitic meta-sedimentary unit with abundant pyrite either visible or observed by scanning electron microprobe. Concentrations of As and S are strongly correlated (r=0.88, p<0.05) in the low grade phyllite rocks, and arsenic is detected up to 1,944 mg kg−1 in pyrite measured by electron microprobe. In contrast, statistically significant (p<0.05) correlations between concentrations of As and S are absent in the calcareous meta-sediments of the Vassalboro Group, consistent with the absence of arsenic-rich pyrite in the protolith. Metamorphism converts the arsenic-rich pyrite to arsenic-poor pyrrhotite (mean As 1 mg kg−1, n=15) during de-sulfidation reactions: the resulting metamorphic rocks contain arsenic but little or no sulfur indicating that the arsenic is now in new mineral hosts. Secondary weathering products such as iron oxides may host As, yet the geochemical methods employed (oxidative and reductive leaching) do not conclusively indicate that arsenic is associated only with these. Instead, silicate minerals such as biotite and garnet are present in metamorphic zones where arsenic is enriched (up to 130.8 mg kg−1 As) where S is 0%. Redistribution of already variable As in the protolith during metamorphism and contemporary water-rock interaction in the aquifers, all combine to contribute to a spatially heterogeneous groundwater arsenic distribution in bedrock aquifers.

Keywords: arsenic, sulfur, pyrite, pyrrhotite, prograde metamorphism, bedrock aquifer

1. INTRODUCTION

Occurrences of arsenic in aquifers in crystalline bedrock have historically received less research attention than those in sedimentary rocks in the many arsenic impacted aquifers across the globe (Bhattacharya et al., 2004; Mukherjee et al., 2009; Smedley and Kinniburgh, 2002). It is increasingly evident that understanding arsenic occurrence in aquifers is not only dependent on the behavior of arsenic during water-rock interaction but also on the distribution of arsenic in rocks influenced by the tectonic cycle (Guillot and Charlet, 2007). Although the literature on arsenic occurrence in whole rock samples is sparse, several recent studies have addressed high temperature arsenic geochemistry in conditions where partial melting (Hattori and Guillot, 2003), geothermal (Arnórsson, 2003; Rango et al., 2010; Sigfusson et al., 2011), or crustal fluid flow into shear zones (Horton et al., 2001) have resulted in various degrees of enrichment of arsenic in a range of rock types. Rudnick and Gao (2003) recommend using As values of 4.8, 3.1 and 0.2 mg kg−1 for the upper, middle and lower crustal rocks respectively, supporting the preference of arsenic for an upward migration due to crustal fluid movement.

In the northeastern United States geogenic arsenic occurrences in bedrock aquifers have been found as far north as Nova Scotia in Canada (Meranger et al., 1984) and extending south into the sedimentary Triassic Rift basins such as the Newark Basin (Peters and Burkert, 2008), Recently it has been suggested (Peters, 2008) that tectonic events in the Northern Appalachian Mountains recycled incompatible arsenic during accretion of multiple terranes in the Ordovician through Jurassic Periods. In contrast, the lower Mesozoic Basins were extensional freshwater basins (Serfes et al., 2005) that accumulated abundant organic matter, sulfur, and arsenic in pyrite, but any deposition and hydrothermal re-concentration of arsenic was the result of rift-basin volcanism, not the hydrothermal activity and veining associated with Paleozoic compressional metamorphism in the New England Appalachians. Both examples show that variable tectonic history has led to arsenic enrichment in the northeastern United States (this issue) since incompatible arsenic likely migrates in tectonic fluids until sequestration and deposition in suitable host mineral phases can occur. Therefore, it is plausible that regional scale fluid migration common in prograde metamorphism can also concentrate or re-distribute arsenic in the upper crust. Few studies, however, have addressed arsenic abundance in regionally metamorphosed rocks where elevated arsenic concentrations in groundwater are naturally occurring (Ayotte et al., 2003; Ryan et al., 2013) and are not derived from anthropogenic contamination. While metamorphic aquifers may not exhibit groundwater yields comparable to sedimentary aquifers they often provide important sources of drinking water to rural communities relying on private wells.

In the Greater Augusta region of central Maine, frequent occurrence of elevated arsenic concentrations (up to 325 µg L−1) in groundwater have been observed for both sulfidic and calcareous meta-sedimentary rocks (Yang et al., 2009). A unique aspect of the central Maine region is that geologic formations have undergone prograde metamorphism with slightly altered marine shales (phyllites and slates) existing in the northeast and changing to progressively higher-grade metamorphic rocks in the southwest (Fig. 1). To our knowledge, this study is the first to address arsenic variation in rocks having undergone progressive (Buchan-type) metamorphism, and where groundwater is impacted by elevated arsenic concentrations. It also adds to aforementioned studies that illustrate the role of tectonic processes in the geochemical cycle of arsenic and provides an improved understanding of arsenic-host minerals in metamorphic rocks to help shed light on the complex hydrogeochemical processes that result in heterogeneous arsenic concentrations in groundwater of these aquifers.

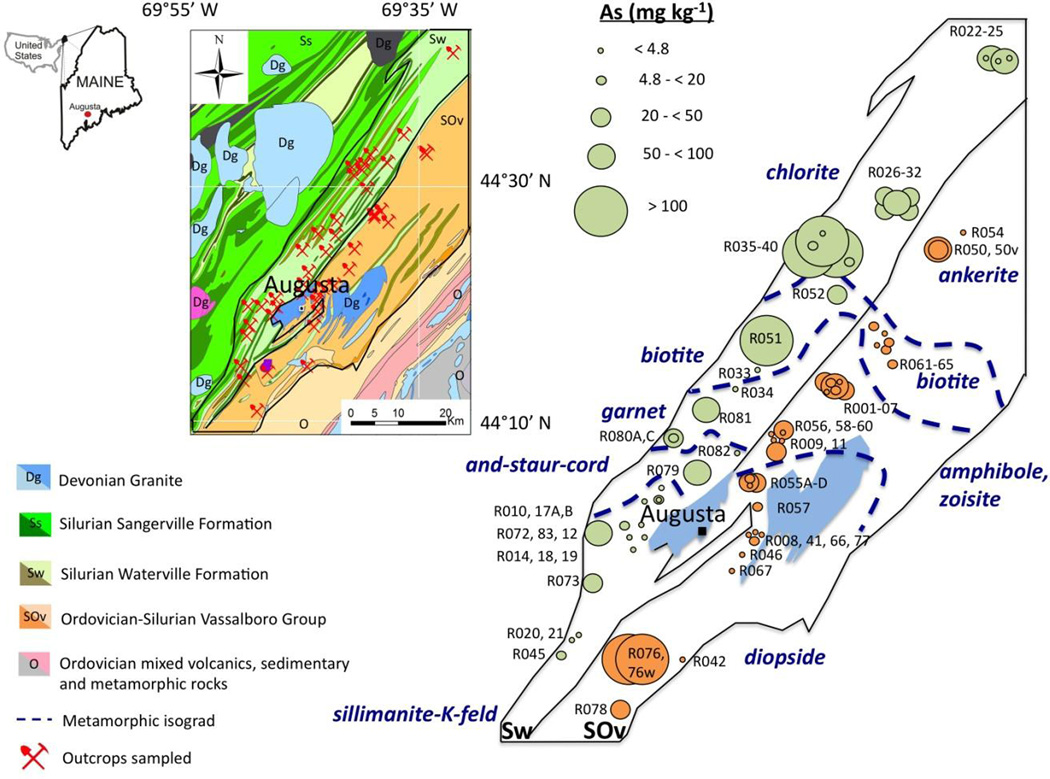

Figure 1.

Location of outcrops and geologic map of the study area (inset). The Waterville and Vassalboro Formations are enlarged (on right) to show concentrations of whole rock arsenic with approximate locations of metamorphic isograds delineated by first appearance of metamorphic index minerals (e.g., chlorite, biotite, garnet, etc.). Rocks collected from outcrops in close proximity may show overlapping arsenic concentration circles. Generalized geology after Osberg et al. (1985).

2. STUDY AREA

The study area is located in central Maine (Figure 1 inset) where a majority of households obtain their drinking water from domestic wells installed into bedrock. The average concentration of As in groundwater is 12.2 µg L−1 (n=790) with 31% of wells containing >10 µg L−1, the EPA Maximum Contaminant Level for drinking water (Yang et al., 2009). Some 12,047 residents were estimated to be at risk of elevated arsenic exposure.

The bedrock consists of meta-sedimentary rocks ranging in age from Ordovician to Silurian (Figure 1) intruded by younger Devonian granitic rocks. Our study area falls within Ganderia, a peri-Gondwanan terrane representing an Ordovician passive margin sequence in the former Iapetus Ocean (Hibbard et al., 2007). Following accretion to Laurentia, the Ordovician sequence was succeeded by Silurian syntectonic, submarine to terrestrial clastic, locally calcareous, sedimentary rocks and associated magmatic rocks of extensional to arc affinity (Hibbard et al., 2010). Limited marine euxinic conditions occurred in our study area during the Silurian. It is thought that these euxinic conditions allowed the accumulation of black shale of limited extent, resulting in the formation of arsenian pyrite according to the model of Peters (2008). Metamorphism during the Acadian Orogeny resulted in progressively higher-grade rocks towards the southwest part of the study area. No evidence was observed for retrograde metamorphism. The understanding of the geology of the area benefits from detailed geologic and metamorphic studies spanning several decades (Osberg, 1968; Ferry, 1978, 1982, 1983a, 1984 and references cited therein).

The following simplified description of the bedrock geology is based on the most recent mapping conducted by the Maine Geological Survey (Marvinney et al., 2010). Two bedrock units with the highest groundwater arsenic occurrence rates (Yang et al., 2009) are chosen for this study: the Ordovician-Silurian Vassalboro Group (SOv) and the Silurian Waterville Formation (Sw). The eastern SOv consists of interbedded argillaceous sandstone, argillaceous carbonate rock and calc-silicate meta-carbonate equivalents with some lithologic layering existing on a local scale (100-101 cm). Mineral isograds mapped by (Ferry, 1983) show first appearance of index minerals formed during progressive metamorphism. For the purpose of this study the degree of metamorphism is simplified following the zones mapped by Ferry: low grade (presence of ankerite and biotite), medium grade (amphibole and zoisite), and higher grade (diopside) (Figure 1). The adjacent and younger Sw formation is a meta-pelite composed of interbedded shale and limestone, argillaceous carbonate rock and argillaceous sandstones. The metamorphic grade increases southwards from low grade (presence of chlorite), through medium grade (appearance of biotite, garnet, and andalusite-cordierite-staurolite) to high grade (sillimanite and sillimanite-K-feldspar) mapped by Osberg (1971). The same scale of lithologic heterogeneity exists as is noted for the SOv, with some layers in the Sw such as graphitic sulfidic rich schist, occurring in discontinuous horizons.

3. METHODS

3.1 Sample collection and preparation

A total of 83 rock samples were collected from exposed roadside and railway cuttings, natural outcrops, drainage ditches and construction holes. While outcrops were sometimes sparse, care was taken to sample different lithologies and different metamorphic grades so that the extent of heterogeneity was represented in the sample population. Given the propensity of arsenic occurrence with pyrite in rocks having undergone metamorphic fluid flow (Pitcairn et al., 2010) pyrite veins observed in low grade rocks were sampled and are designated with a ‘v’ in Table 1. Where rock samples from one outcrop exhibit many different lithologies multiple samples were collected (A, B, C, etc. in Table 1). Samples (n=7) collected near metamorphic contact aureoles or in the granites and adjacent Sangerville Formation were not included in this study so as to focus only on the Sw (n=38) and SOv (n=38) units impacted by regional (prograde) metamorphism.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of meta-sedimentary rocks, Central Maine.

| Sample ID | Sample Location | Index Mineral | Fe2O3Tot | MnO | Total S | Total C | Total As | As extracted* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | West | % | % | % | % | mg/kg | mg/kg | ||

| Waterville Formation Sw | |||||||||

| Low grade rocks | |||||||||

| R022^ | 44°47' | 69°24' | minor chlorite | 6.45 | 0.02 | 5.17 | 1.55 | 87.9 | 87.0 |

| R023^ | 44°47' | 69°24' | minor chlorite | 9.03 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 3.0 | <2 |

| R024 A | 44°47' | 69°24' | minor chlorite | 8.17 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 2.8 | 2.5 |

| R024 B^ | 44°47' | 69°24' | minor chlorite | 5.90 | 0.72 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 4.1 | <2 |

| R025 | 44°47' | 69°24' | minor chlorite | 2.78 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.11 | 58.4 | <2 |

| R026 A^ | 44°38' | 69°32' | chlorite | 10.59 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 1.65 | 22.5 | 11.0 |

| R026 B^#** | 44°38' | 69°32' | chlorite | 11.00 | 0.85 | 4.21 | 1.52 | 83.6 | 66.9 |

| R029 | 44°38' | 69°32' | chlorite | 3.13 | 1.32 | 0.01 | 6.00 | 33.3 | 29.0 |

| R031 | 44°38' | 69°32' | chlorite | 7.83 | 1.02 | 0.00 | 1.31 | 21.9 | 12.5 |

| R032 | 44°38' | 69°32' | chlorite | 6.71 | 1.01 | 0.10 | 1.48 | 22.2 | 16.2 |

| R035 | 44°34' | 69°40' | chlorite | 8.34 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 1.6 | <2 |

| R036 | 44°36' | 69°37' | chlorite | 5.89 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 12.9 | 19.0 |

| R037** | 44°35' | 69°38' | chlorite | 14.68 | 0.04 | 7 | 0.80 | 137.9 | 82.7 |

| R038 | 44°35' | 69°38' | chlorite | 10.58 | 0.02 | 2.66 | 1.28 | 114.2 | 116.0 |

| R039 | 44°35' | 69°40' | chlorite | 4.82 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 19.2 | 19.0 |

| R040 | 44°34' | 69°39' | chlorite | 4.76 | 0.01 | 4.07 | 0.51 | 133.5 | <2 |

| Medium grade rocks | |||||||||

| R033^ | 44°29' | 69°43' | biotite | 7.30 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.05 | <2 | <2 |

| R051 | 44°33' | 69°35' | biotite | 19.13 | 4.11 | 0.00 | 3.61 | 130.8 | 130.0 |

| R052 | 44°35' | 69°32' | biotite | 7.42 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 2.73 | 24.0 | 13.2 |

| R034^#** | 44°27' | 69°43' | garnet | 9.26 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 4.3 | <2 |

| R080 A | 44°25' | 69°47' | garnet | 8.14 | 0.70 | 0.23 | 1.98 | 6.5 | <2 |

| R080 C | 44°25' | 69°47' | garnet | 6.88 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 4.22 | 42.9 | 46.0 |

| R081** | 44°27' | 69°45' | garnet | 17.47 | 2.40 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 70.1 | 42.1 |

| R079 | 44°21' | 69°47' | and-staur-cord | 7.32 | 0.43 | 1.09 | 0.75 | 70.9 | 76.0 |

| R082 | 44°25' | 69°44' | and-staur-cord | 7.13 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.13 | <2 | <2 |

| High grade rocks | |||||||||

| R010 | 44°21' | 69°48' | sillimanite | 3.86 | 0.09 | 0.94 | 0.77 | <2 | 0.9 |

| R012 | 44°19' | 69°50' | sillimanite | 10.79 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.12 | <2 | <2 |

| R014 | 44°20' | 69°52' | sillimanite | 14.60 | 1.42 | 0.58 | 0.14 | <2 | <2 |

| R017 A^# | 44°20' | 69°52' | sillimanite | 12.43 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 3.3 | <2 |

| R017 B | 44°20' | 69°52' | sillimanite | 10.87 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 9.1 | 9.1 |

| R018 | 44°17' | 69°56' | sillimanite | 4.44 | 0.06 | 4.75 | 0.56 | <2 | <2 |

| R019 | 44°16' | 69°57' | sillimanite | 4.62 | 0.07 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 4.5 | 3.1 |

| R072** | 44°19' | 69°56' | sillimanite | 10.08 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 58.0 | 63.0 |

| R083 | 44°19' | 69°54' | sillimanite | 7.63 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 7.4 | 24.0 |

| R045^** | 44°09' | 70°02' | sillimanite-Kfeld | 5.40 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 11.3 | <2 |

| R020 | 44°17' | 69°56' | sillimanite-Kfeld | 8.83 | 0.20 | 0.65 | 0.18 | <2 | <2 |

| R021 | 44°17' | 69°56' | sillimanite-Kfeld | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 2.2 | 5.0 |

| R073 | 44°14' | 69°58' | sillimanite-Kfeld | 8.66 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 38.1 | <2 |

| Vassalboro Group SOv | |||||||||

| Low grade rocks | |||||||||

| R050v | 44°36' | 69°19' | ankerite | 5.97 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 1.23 | 54.2 | 52.0 |

| R050 | 44°36' | 69°19' | ankerite | 6.67 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 43.6 | 45.0 |

| R054 | 44°37' | 69°23' | ankerite | 3.11 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 1.98 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| R061 | 44°29' | 69°36' | biotite | 3.99 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 3.2 | <2 |

| R062 | 44°29' | 69°36' | biotite | 5.43 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 5.4 | <2 |

| R063 | 44°29' | 69°36' | biotite | 5.54 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 2.8 | <2 |

| R064 | 44°29' | 69°35' | biotite | 2.63 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 1.83 | 8.2 | <2 |

| R064w | 44°29' | 69°35' | biotite | 4.08 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 14.3 | <2 |

| R065 | 44°28' | 69°34' | biotite | 12.33 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 14.8 | 19.0 |

| Medium grade rocks | |||||||||

| R059 | 44°25' | 69°39' | amphibole | 3.7 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 4.2 | <2 |

| R060 | 44°25' | 69°39' | amphibole | 4.6 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.13 | <2 | <2 |

| R058 | 44°23' | 69°40' | amphibole | 5.0 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.06 | <2 | <2 |

| R056 | 44°21' | 69°44' | zoisite | 3.85 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | <2 | <2 |

| R001 | 44°20' | 69°46' | zoisite | 8.68 | 0.08 | 5.97 | 0.60 | 9.7 | 18.0 |

| R002 | 44°20' | 69°46' | zoisite | 3.45 | 0.03 | 4.81 | 1.31 | 4.0 | 7.0 |

| R003 | 44°20' | 69°46' | zoisite | 1.91 | 0.06 | 0.72 | 0.05 | 5.9 | 2.3 |

| R004 | 44°20' | 69°46' | zoisite | 8.42 | 0.06 | 13.22 | 1.12 | 34.4 | 76.0 |

| R005 A | 44°20' | 69°46' | zoisite | 5.12 | 0.10 | 1.03 | 0.49 | 31.8 | 86.0 |

| R005 B | 44°20' | 69°46' | zoisite | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.10 | <2 | <2 |

| R006 | 44°20' | 69°46' | zoisite | 7.42 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 3.0 | 2.1 |

| R007 | 44°20' | 69°46' | zoisite | 7.75 | 0.08 | 1.65 | 0.24 | 69.1 | 69.0 |

| R009 | 44°21' | 69°48' | zoisite | 3.92 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 23.8 | 34.0 |

| R011 | 44°20' | 69°46' | zoisite | 4.11 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.28 | 40.5 | 16.6 |

| High grade rocks | |||||||||

| R055 A | 44°20' | 69°45' | diopside | 3.73 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.03 | <2 | <2 |

| R055 B | 44°20' | 69°45' | diopside | 3.59 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 10.3 | 10.0 |

| R055 C | 44°20' | 69°45' | diopside | 2.02 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1.57 | 26.5 | 28.0 |

| R055 D | 44°20' | 69°45' | diopside | 4.34 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 26.5 | 26.0 |

| R066 | 44°23' | 69°35' | diopside | 2.16 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.07 | <2 | <2 |

| R077 | 44°12' | 69°53' | diopside | 3.11 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 14.6 | 17.0 |

| R041 | 44°20' | 69°46' | diopside | 6.11 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.02 | <2 | <2 |

| R067 | 44°18' | 69°45' | diopside | 2.98 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 2.6 | <2 |

| R076 | 44°11' | 69°57' | diopside | 7.58 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 115.7 | 93.7 |

| R076w | 4411' | 69°57' | diopside | 4.33 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 117.2 | 134.0 |

| R078 | 44°07' | 69°54' | diopside | 8.12 | 0.15 | 3.36 | 0.22 | 26.3 | 21.0 |

| R057 | 44°21' | 69°42' | diopside | 12.26 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 6.1 | <2 |

| R008 | 44°20' | 69°46' | diopside | 4.83 | 0.04 | 1.64 | 0.45 | 4.7 | 4.7 |

| R042 | 4413' | 69°47' | diopside | 9.04 | 0.27 | 2.99 | 0.86 | <2 | <2 |

| R046 | 4417' | 69°46' | diopside | 1.36 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | <2 | <2 |

| QA/QC | |||||||||

| NIST 2702 | certified value | 1.5 | 3.36 | ||||||

| NIST 2711 | certified value | 105 | |||||||

| NIST 2710 a | certified value | 4.32 | 0.214 | ||||||

| mean of replicates analysed herein: | 4.69 | 0.221 | 1.6 | 3.18 | 99 | ||||

| RPD % | 8.6 | 3.3 | 6.7 | −5.4 | −5.7 | ||||

Total As, Fe2O3Tot and MnO measured by Innov-X-5000 XRF at USD

Total %S and %C were analyzed by Elementar CHNS Analyzer at USD

As extracted by microwave assisted HNO3 at USD. Sensitivity differences between instruments and methods may lead to As extracted > total As

Where 2 of the same sample ID exist notable lithologic differences resulted in the collection of multiple samples: A, B, C, etc., or v=vein, w=weathered

Bolded samples were collected in the rare black shale unit of the Sw

subset of this sample was oxidatively and reductively leached (results in Supplementary Table 1)

sample was photographed in thick section (Figure 2)

minerals in this sample were analyzed for As by electron microprobe

RPD % = ((mean of replicates - certified value) / (certified value))*100

Samples were logged and photographed in the field and laboratory prior to further processing. To target primary minerals, the weathered rinds were selectively cut out from the unweathered parts of the rock samples. In a few cases weathered rinds were difficult to separate and although the majority of the rock was considered fresh these samples are denoted with a ‘w’ in Table 1 to reflect the possibility of secondary minerals making up a minor component of the sample. Each was pulverized into fine powders using a Bico Pulverizer with ceramic plates in the Rock Shop at the University of San Diego (USD). A diamond tipped rock saw at CUNY Queens College was also employed to cut rock samples into slabs that were subsequently polished for Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) and Electron Microprobe (EM) analysis. All equipment was cleaned with compressed air and acetone to prevent cross contamination between samples. Clean quartz sand was passed through the pulverizer if ceramic plates became stained.

3.2 Whole rock, acid digested, and electron microprobe analysis

Total elements (Table 1) were analyzed by X-ray fluorescence prior to microwave assisted acid digestion (EPA Method 3051A). Arsenic in sulfide minerals was analyzed by electron microprobe following procedures outlined in Lowers et al., (2007). Details of each method are provided in the Supplementary Data.

3.3 Reductive and Oxidative Leaching

Fifteen Sw rock powders were reductively and then oxidatively leached at CUNY Queens College. Reduction was achieved by following a method described in Chester and Hughes (1967) targeting ferro-magnesian and carbonate minerals in pelitic sediments. A solution of 5 mL of 1M hydroxylamine hydrochloride in 25% acetic acid was added to 0.5 g rock powder and shaken at room temperature for 4 hours. For context, Tessier et al., (1979) found this same reagent combination to be most effective at keeping liberated metals in solution compared to other combinations of reductive reagents they tested. Samples were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes until the supernatant had separated and could be collected for analysis. The reduced sediment was then rinsed three times with Milli-Q water in preparation for oxidation following EPA Method 3050B. With the breakdown of ferromagnesian and carbonate minerals already completed by reduction, the oxidation step was carefully selected to use lower temperatures and a different mix of chemicals so as not to attack the crystalline matrix as vigorously as the nitric acid extraction. Rinsed and reduced rock powder was mixed with 10 mL of trace element grade HNO3 and heated to only 80°C in a Fisher Scientific Isotemp 205 isotherm bath for 16 hours. Samples were allowed to cool before addition of 1.5 mL of H2O2 and placed into the isotherm bath for an additional 2 hours before the final supernatant was collected for analysis. Leachate solutions including a full range of duplicates and blanks were analyzed for Fe, Mn, S and As by HR-ICP-MS at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University following a method described by Cheng et al. (2004).

3.4 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS Statistical Software Version 19. To assess differences in As concentration between different metamorphic grades non-parametric As data were tested for homogeneity of variance by difference of ranked means of each metamorphic grade, and a one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to show statistical significance was >0.05, i.e., homogeneity of variance existed between metamorphic grades. Then a Kruskall-Wallis test was used to assess statistical significance. If p<0.05, then subsequent post-hoc testing was performed between each metamorphic grade to identify where the statistical difference lies.

4. RESULTS

4.1 Total Arsenic Concentrations

The total concentration of As in rocks from Central Maine ranges from non-detectable (< 2 mg kg−1) to 138 mg kg−1 (Table 1). The 76 samples contain an average of 28.6 mg kg−1 As (median 17.0 mg kg−1) with 58% of them exceeding the average As concentration of 4.8 mg kg−1 proposed by Rudnick and Gao (2003) for the Earth’s upper crust. A review of arsenic concentrations in metamorphic rocks (Smedley and Kinniburgh, 2002) indicates that most contain around 5 mg kg−1 As and often reflect concentrations originally present in their protoliths, with marine pelitic protoliths typically reporting the greatest As concentrations, on average ∼18 mg kg−1. In contrast, however, these rocks from Central Maine appear to be further enriched although it is not known if the reported averages in the literature take into account varying degrees of metamorphism.

The range and variability in arsenic concentrations is similar across the two geologic units (minimum <2 mg kg−1 As to a maximum of 138 mg kg−1 As and maximum 117 mg kg−1 As for Sw and SOv, respectively) although the Sw contains average higher arsenic concentrations (mean As 32.9 mg kg−1 and median 12.1 mg kg−1) than the SOv (mean As19.1 mg kg−1 and median 6.0 mg kg−1). Some other trends are noted, for example, average As concentrations decrease from 47.4 mg kg−1 in low grade Sw rocks, to 39.0 mg kg−1 As in medium grade Sw rocks, to only 10.8 mg kg−1 As in the high grade Sw rocks. Kruskall-Wallis statistical testing reports only a slight difference (p=0.059) and post-hoc testing revealed that the statistical difference exists only between the mean As reported for low and high grade Sw rocks (p=0.012) but not for low-medium or medium-high grade comparisons which is also reflected in median As concentrations of 22.4, 24.0, and 3.3 mg kg−1 respectively across each metamorphic grade. The opposite trend is reported for the Vassalboro Group where average As concentrations increase from low grade (16.7 mg kg−1 As), to medium grade (22.6 mg kg−1 As), to high grade (35.1 mg kg−1 As) in the SOv metamorphic rocks. However, Kruskall-Wallis statistical testing shows a p value of 0.778 for comparison of mean As concentrations in all grades of the SOv indicating that there is no statistical difference between average As concentrations across the different metamorphic grades of the SOv Formation. This is supported by median As concentrations of 8.2, 5.1, and 6.1 mg kg−1 in low-medium-high grade SOv rocks. Overall, As is elevated in these metamorphic rocks compared to other studies and changes in As concentration with progressive metamorphism are only significant in the Sw; with As concentrations decreasing significantly between low and high grade rocks.

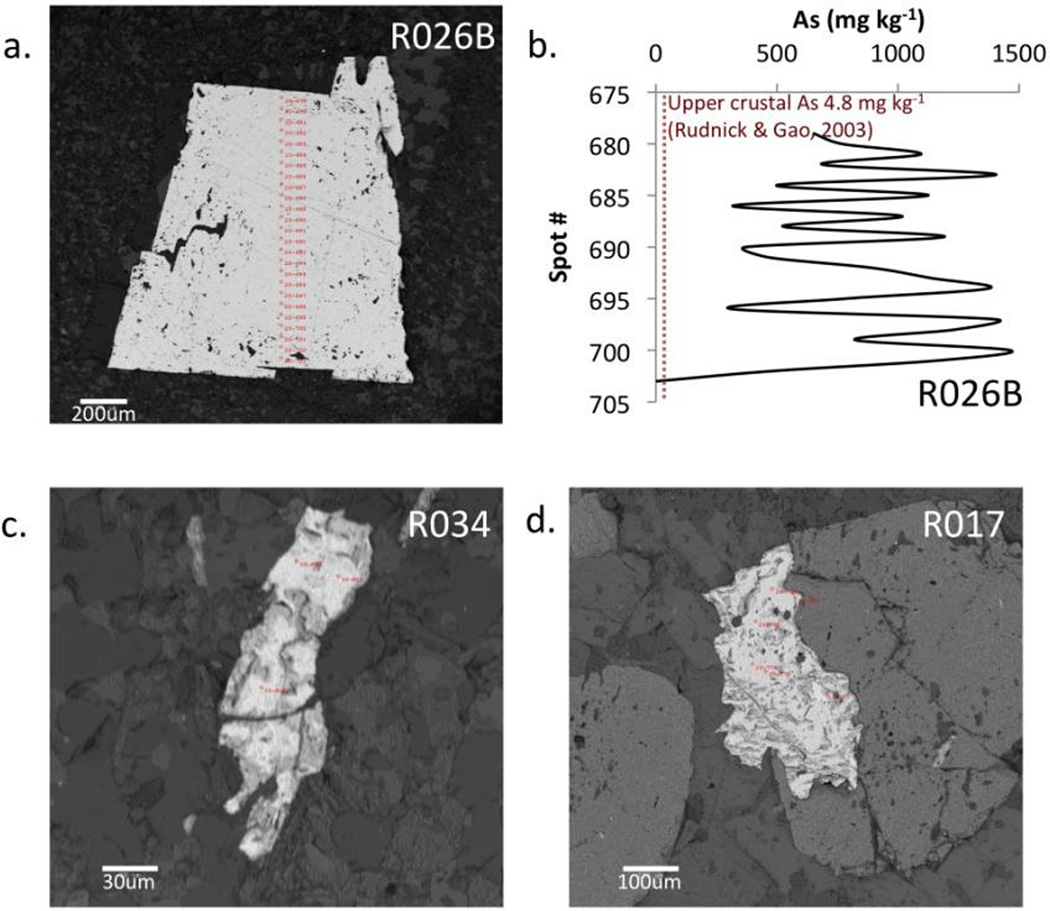

4.2 Sulfide Mineralogy

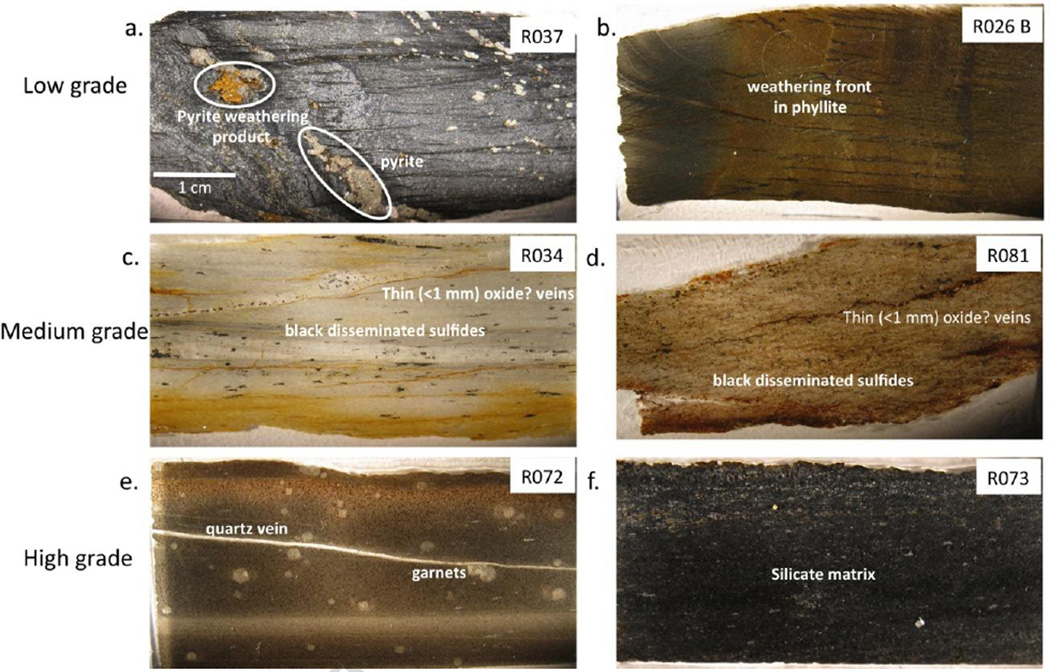

Diagenetic and metamorphic pyrites are observed in outcrop and hand specimen. Figure 2a shows a pyrite vein aligned with bedding (inclined to the long dimension of the slide). Porphyroblasts range from mm-scale to 1–2 cm in diameter while veins contain pyrite cubes approximately 1–5 mm in diameter. Field observations of pyrite were common in low-grade rocks and rare in medium and high-grade rocks. In thin section, disseminated sulfides are observed in medium and high-grade rocks and are frequently <1 mm in diameter (Figure 2c, d).

Figure 2.

Photographs of rock thin sections backlit on an optical light table. Refer to Figure 1 for sample locations. Two sections from each metamorphic grade were chosen to best represent the variation in lithology and degree of alteration encountered. Scale bar is the same for each photograph.

Pyrite and pyrrhotite were distinguished with atomic ratios measured by SEM-EDX (Table 2). In low grade rocks iron/sulfur atomic ratios of 0.2–0.4 (close to the 0.5 molar ratio expected for pyrite) were observed concurrent with elevated As concentrations (e.g., R026 B). Iron/sulfur ratios increased to 0.9–1.4 in medium and high-grade rocks where pyrrhotite (Fe/S ratio close to 1.0) appears to be the dominant sulfide mineral and whole rock As concentrations decrease to approximately 3–5 mg kg−1 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of iron sulfide minerals by SEM-EDX in select samples from the Waterville Formation

| Sample ID | Index Mineral |

Fe atomic % |

S atomic % |

Fe/S atomic % |

Sulfide Mineral |

Total As* mg/kg |

As extracted* mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R026 B | low grade chlorite | 3.73 | 22.48 | 0.2 | pyrite? | 83.6 | 66.9 |

| R026 B | low grade chlorite | 6.83 | 19.43 | 0.4 | pyrite | 83.6 | 66.9 |

| R026 B | low grade chlorite | 6.94 | 19.46 | 0.4 | pyrite | 83.6 | 66.9 |

| R034 | medium grade biotite | 14.78 | 15.52 | 1.0 | pyrrhotite | 4.3 | <2 |

| R017 A | high grade sillimanite | 15.35 | 14.20 | 1.1 | pyrrhotite | 3.3 | <2 |

| R017 A | high grade sillimanite | 13.21 | 15.13 | 0.9 | pyrrhotite | 4.3 | <3 |

| R017 A | high grade sillimanite | 18.16 | 12.96 | 1.4 | pyrrhotite? | 5.3 | <4 |

| R045 | high grade sill-K-feld | no sulfide minerals observed during SEM | 11.3 | <2 | |||

Data from Table 1

4.3 Arsenic and Sulfide

Whole rock sulfur content is generally below 1% but 11 samples have anomalous S values between 2 and 13% (Table 1). Strong positive correlations exist for As and S% in low grade Sw rocks (r=0.88, p<0.05; Table 3). A moderate positive correlation exists between total Fe and S in Waterville low-grade rocks (r=0.51, p<0.05) and Vassalboro medium (r=0.55, p<0.05) grade rocks.

Table 3.

Geochemical relationships (Pearsons r) in bulk rocks of the Sw and SOv geologic units.

| Waterville Formation | Vassalboro Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total As | Total S | Total As | Total S | |

| Low Grade | ||||

| Fe2O3Tot | 0.31 | 0.51 | 0.26 | −0.07 |

| MnO | −0.34 | −0.48 | ||

| Total S | 0.88 | 0.15 | ||

| Total C | 0.08 | 0.15 | ||

| Medium Grade | ||||

| Fe2O3Tot | 0.77 | −0.3 | 0.44 | 0.55 |

| MnO | 0.86 | 0.52 | ||

| Total S | 0.17 | 0.24 | ||

| Total C | 0.44 | 0.16 | ||

|

High Grade |

||||

| Fe2O3Tot | 0.18 | −0.26 | 0.11 | 0.45 |

| MnO | −0.15 | −0.02 | ||

| Total S | −0.28 | −0.16 | ||

| Total C | −0.25 | −0.04 | ||

Correlations significant at the p<0.05 level are bolded. Those significant at p<0.10 are underlined.

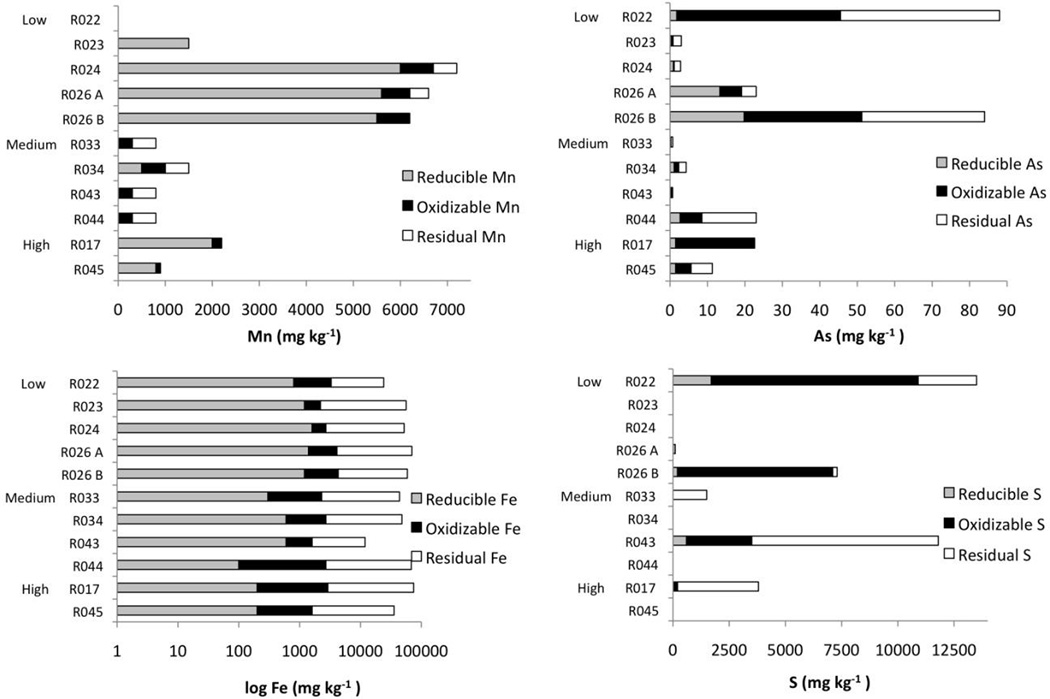

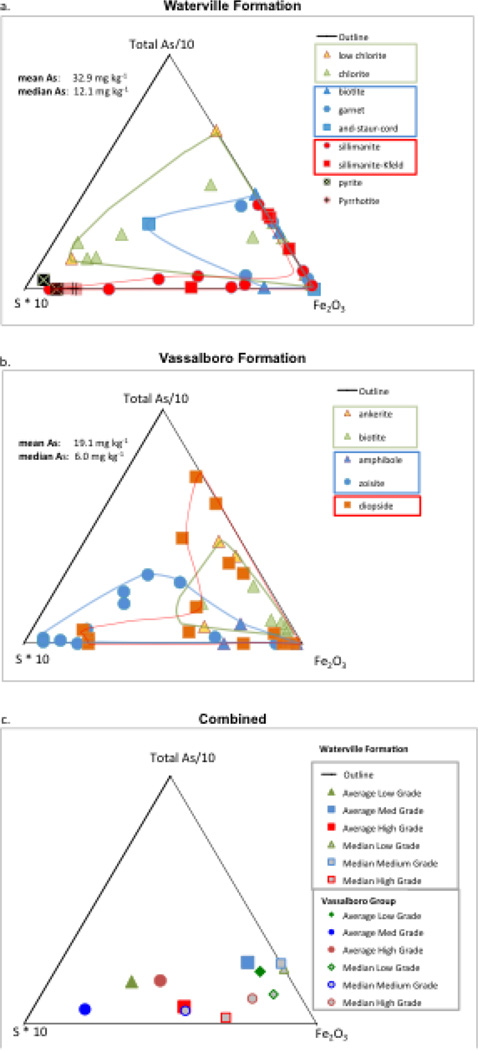

Simultaneous oxidative release of S and As is observed in two of the low grade Sw rocks (R022 and pyritic R026B; Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1) but in the high grade rock (R017) As is oxidatively released when S is not. In fact, some of the highest arsenic occurs in rocks where S was at or below detection limits (R051 and R076, respectively; Table 1). Also, the whole rock geochemistry shows several instances where elevated concentrations of arsenic are present when sulfur is absent. For example, although total As concentration was 11.3 mg kg−1 for the high grade rock sample R045, no sulfide minerals were observed using SEM examination, and no S was detected via CHNS analyzer. This trend is particularly common throughout the SOv rocks and the medium and high-grade Sw rocks as illustrated in Figure 4 where total arsenic and sulfur were normalized (As divided by 10 and S multiplied by 10) in order to compare relative proportions of As, S, and Fe2O3 across different metamorphic grades and between the two geologic units. Specifically, Figure 4a indicates the absence of As-rich sulfides in the higher-grade meta-sedimentary rocks of the Sw compared to rocks from the lower grades that cluster closer to the As vertex. Contrast with the SOv rocks (Figure 4b) to see that As is less influenced by sulfides particularly in low grade SOv rocks. When both units are compared in Figure 4c the average concentrations of S, As, and iron in each grade show more S influence for low grade Sw and low- and medium- SOv contrasting with low S grades with elevated As (e.g., Sw medium grade rocks).

Figure 3.

Oxidative and reductive leach results for Mn, As, Fe and S on selected Sw samples. Cumulative leach results were compared against total concentrations measured by XRF and thus excess concentrations that were not successfully leached are labeled as residual. Note the log scale for Fe.

Figure 4.

Relative proportions of total arsenic, sulfur and iron in the Waterville (a) and Vassalboro (b). Arsenic and sulfur are normalized (As/10 and S*10) to enable proportionate comparisons to total iron. Samples are grouped by grade with low grade (green), medium grade (blue) and higher grade (red) clustered into groups. Pyrite and pyrrhotite are shown for reference in plot (a). In (c) the average and median concentrations of each element are plotted for each grade to allow comparison between geologic units and metamorphic grades.

4.4 Arsenic-rich Pyrite and Arsenic-poor Pyrrhotite

The whole rock geochemistry is compatible with, but does not directly measure, arsenic association with sulfide minerals. Electron microprobe was subsequently employed to directly measure the concentration of arsenic in pyrite and pyrrhotite. Arsenic concentrations in pyrite average 706 +/− 451 mg kg−1 (n=115) compared to an average of only 1 +/−1 mg kg−1 As in pyrrhotite (n=15) (Figure 5). It is worth noting that pyrrhotite grains observed in thin section appeared to have grown to replace pre-existing minerals by exhibiting irregularly-shaped boundaries truncating the surrounding silicate minerals. Pyrrhotite in these higher-grade rocks is thus likely metamorphic rather than diagenetic.

Figure 5.

Electron microprobe spot analyses of As concentrations in pyrite and pyrrhotite. Low grade R026B pyrite crystal with spot analysis locations (a) and subsequent line-scan showing As concentrations (b), and pyrrhotite in medium grade R034 (c) and high grade R017 (d) rocks. No As was detected in the spots shown in (c) and (d).

4.5 Arsenic Association with Iron and Manganese

Major element compositions in rocks of both geologic units have been reported Ferry (1981, 1983b). For this study we focus on elements of most relevance to arsenic: S, Fe, Mn, and C. In both the medium and high-grade rocks, biotite, garnet and other silicate minerals appear (Figure 2c–f) as whole rock sulfur decreases with increasing metamorphism (Table 1) directing the study towards investigating associations between As and elements other than sulfur. A strong positive correlation exists between As and Fe2O3 in medium grade Sw rocks (Table 3, r=0.77, p<0.05). Total iron is also higher in the Sw (where As averages are higher), averaging 8.5% compared to 5.2% total iron in SOv. Concentrations of Fe that were reductively leached (Figure 3) are low by comparison to total iron concentrations and reducible As concentrations are also generally low. For example, in the pyritic R026B the concentration of reducible As is 19.8 mg kg−1 which represents only 24% of the total As present in that rock compared to 37% of the As that was oxidatively leached.

The Waterville Formation contains average concentrations of Mn that are an order of magnitude higher than the adjacent Vassalboro Group. Manganese in some rocks was effectively mobilized by reduction (R023, R024, R026B) while in others Mn was more effectively released by oxidation (R033, R043, R044; Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1). Arsenic concentrations, however, were neither oxidized nor reduced in obvious tandem with Mn but a strong positive correlation exists between total As and MnO in some rocks (e.g., medium grade Sw rocks r=0.86, p<0.05) perhaps indicating an unknown association between arsenic and manganese minerals.

The low and medium grade Sw rocks have a mean C content of >1% while all the metamorphic grades in the SOv have a lower mean C content of <0.7%. Graphitic schist layers extend discontinuously throughout the Waterville Formation and were most commonly encountered in the low-grade rocks. However, correlations between total As and C in both formations were generally poor (r< 0.2; Table 3), insignificant, and often negative. It is possible that As-host minerals, such as pyrite, may occur within the layers of graphitic schists. This possibility requires further investigation.

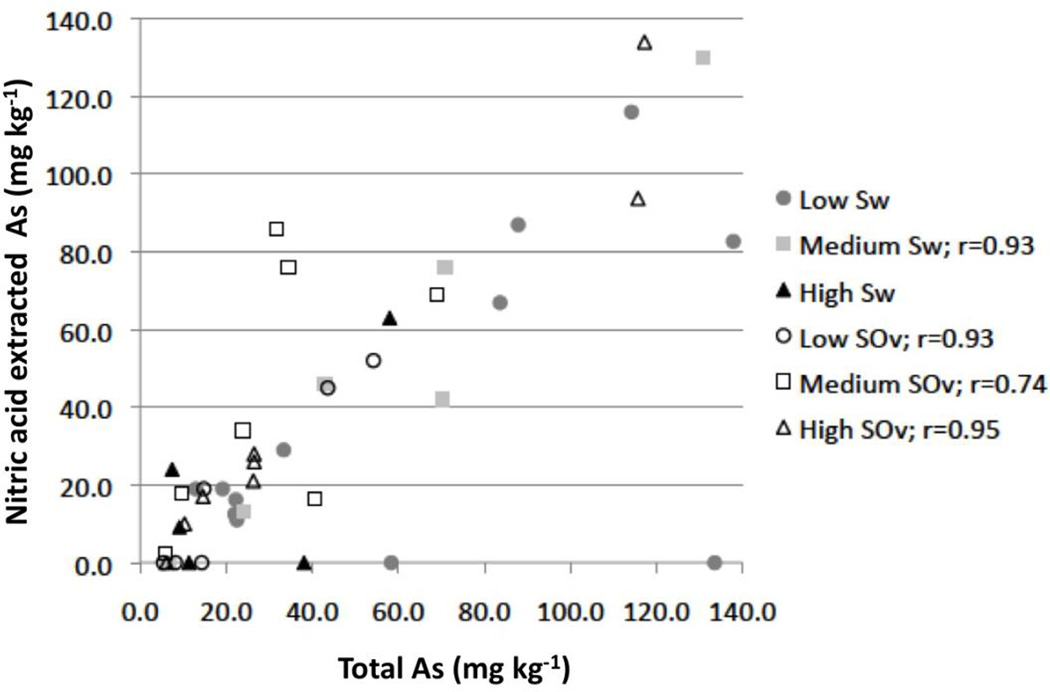

4.6 Arsenic by Nitric Acid Extraction

Concentrations of As that can be extracted with HNO3 range from non detectable (< 2 mg kg−1) to 134 mg kg−1 (Table 1). In general, the ability of As to be extracted correlates very well with the total concentration of As in the rock, with four of the six metamorphic grades (across both units) showing strong r values at the p<0.05 level (Figure 6). Two metamorphic grades do not show a statistically acceptable relationship (p>0.05) between total As present and its ability to be extracted by HNO3; the pyrite-rich low grade Sw and the pyrite-poor high grade Sw rocks. Interestingly, these are the same two grades that show a statistical difference in mean As concentration reported by the Kruskall-Wallis test and could indicate multiple As host minerals across different grades.

Figure 6.

Total As versus HNO3 extractable As for each grade of the Sw and SOv. Only correlations that are significant at p<0.05 level are shown. The r value for medium grade SOv was calculated without samples R004 and R005 which extracted more As than total As indicating slight inaccuracies can exist between the analytical methods employed.

Although strong correlations are observed between nitric acid extraction and arsenic concentrations there are also cases where the data appear heterogeneous. For example, some samples (n=2) with high concentrations (>50 mg kg−1) of total As have no HNO3 extractable As, while other samples with similar concentrations of total arsenic have 100% extractable As. For example, rocks R040, R037 and R038 which were collected in the low grade Sw less than 1 kilometer apart each contain >110 mg kg−1 total As (Table 1) but have 0, 60, and 100% extractable As respectively.

Both the reductive/oxidative leach and nitric extractable arsenic data show heterogeneous arsenic release that indicate there are likely As-host minerals that include arsenian pyrite and possibly non-sulfide and non-oxide As minerals.

5. DISCUSSION

5.1 Arsenic Enrichment in Central Maine Metamorphic Rocks

Arsenic in the Sw and SOv in central Maine are, on average, more enriched than most published values of arsenic in metamorphic rocks. Boyle and Jonasson (1973) report an average of 18 mg kg−1 for slates and phyllites compared to 33 mg kg−1 reported in this study. Similarly, an average of 1.1 mg kg−1 As for schists and gneisses (Smedley and Kinniburgh, 2002) compares to the average 27 mg kg−1 As found in the schists and gneisses of the Sw and SOv. There are three possible explanations for this enrichment. One is the process proposed by Peters (2008) and also by Mango and Ryan (this issue) that arsenic was likely enriched in marine pyrites present in the pelitic protoliths. Pyrite is the most common sulfide mineral in marine sediments due to sulfide enrichment in anoxic pore waters and trace element incorporation has been well studied, including the long-term preservation of arsenic in marine pyritic sediments (Large et al., 2014). A second possible enrichment process entails large-scale fluid flow during metamorphism. This process is proposed by Goldhaber et al. (2003) as the source of arsenian pyrite deposition in the Southern Appalachian region and is further elaborated on in the next section. A third possible explanation for the anomalously high As concentration in these metamorphic rocks is the scarcity of published data on arsenic concentrations in metamorphic (and igneous) rocks: our current knowledge on representative arsenic concentrations in rocks may require revision.

There appears to be no major trend between bulk rock arsenic concentration and metamorphic grade. There exists only a minor statistical difference between low grade and high grade Sw rocks which may indicate a decrease in arsenic concentrations with increasing metamorphic grade, however, no statistical difference was observed between different grades of the SOv. When comparing the two geologic units, the generally greater concentrations of arsenic observed in the Sw compared to the SOv may be a product of their original protolith composition. Sw is more pelitic and includes discrete limestone units, rare black shales, and more pyrite. SOv is less pelitic and includes limy sandstones. It is likely that the coarse, proximal turbidites of the SOv retain less As than the finer-grained distal turbidites of the Sw which are pelite-rich. It may also be true that for the more pelitic host, metamorphism may have resulted in a more complex mineral assemblage with more likelihood of retaining or enriching arsenic.

5.2 Arsenic Loss from Host Sulfide Minerals during Metamorphism

The association between arsenic and pyrite is common (Large et al., 2012; Savage et al., 2000; Tabelin et al., 2012). Arsenic association with pyrite in low-grade meta-sedimentary rocks from central Maine was confirmed by electron microprobe where pyrite occurs at the cm-scale. Further, total As concentrations are enriched in samples where pyrite crystals or veins were observed (R022 shows 18 times more As than the reported average of 4.8 mg kg−1 for metamorphic rocks, and R037 shows 28 times more As enrichment; Table 1). The ability of arsenic to be released by oxidative leaching (R022 and R026B in Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1) implies arsenian pyrite as a host mineral.

Concentrations of arsenic measured in the Sw pyrites (up to 1,944 mg kg−1) are consistent with concentrations measured in pyrites present in low grade slates in nearby southwestern Vermont (Ryan et al., 2013) where calculated As concentrations in pyrite are between 236 and 2,074 mg kg−1 indicating an enrichment of arsenic in the shale protolith occurred as marine depositional conditions became more anoxic. Mango and Ryan (this issue) present a convincing case through the use of sulfur isotopes to show that the sulfur isotopic composition of sedimentary/diagenetic pyrite in their marine protolith reflects the change in redox conditions during protolith deposition and arsenic uptake in pyrites increased as sedimentary conditions became more anoxic. The protolith under investigation in southwestern Vermont belongs to the Taconic physiographic province and was deposited during the late Cambrian to the late Ordovician when the closing of the Iapetus Ocean changed the marine sedimentary environment from oxidizing to a deep reducing basin. While arsenic is enriched in sedimentary pyritic rocks studied here these black shale units of the Sw are rare and thus many rocks in our study were likely subject to less anoxic conditions than the rocks analyzed in Vermont.

Later metamorphism, however, may also influence the occurrence and distribution of arsenian pyrite in metamorphic bedrock. Ferry (1981) measured a change in molar pyrite/ (pyrite+pyrrhotite) in the Sw as a function of metamorphic grade and found that despite the wide variation in both pyrite and pyrrhotite occurrence in all metamorphic grades, and a relatively low sample population, there appears to be a lower occurrence of pyrite in samples of the higher-grade rocks where sillimanite is present. In fact, the difference in mean pyrite/ (pyrite+pyrrhotite) ratio between all Sw low-grade rocks and all those in the higher grades was found to be significant at a >99.9% confidence level. Ferry (1981) subsequently proposed the following as one form of a reaction for de-sulfidation in the Sw:

A consequence of this reaction would be that whole rock iron contents remain unaffected but whole rock sulfur decreases as reaction proceeds. In light of lithologic heterogeneity observed here, a measure of whole rock Fe/S ratios rather than whole rock Fe% is used to evaluate the loss of S with increasing metamorphism, essentially leading to an increase in the whole rock Fe/S ratio in low through high grade rocks if Ferry’s proposed reaction is occurring. The rocks herein support this reaction by showing an increase in whole rock Fe/S from low grade Sw (Fe/S mean 9.2), to medium grade Sw (Fe/S mean 25.0), increasing to high grade Sw (Fe/S mean 43.3) showing a decrease in S relative to Fe with increasing metamorphism.

The transition from pyrite to pyrrhotite is also supported by field observation, with occurrences of pyrite cubes and veins disappearing in medium and higher-grade outcrops. SEM scans show the same trend in that sulfide minerals analyzed in medium and higher grade rocks are indicative of atomic ratios closer to pyrrhotite (Table 2). These visual observations qualitatively support Ferry’s de-sulfidation hypothesis. If pyrite is converted to pyrrhotite during progressive metamorphic reactions, and this study found these pyrites to be enriched in arsenic the obvious question then arises, is pyrrhotite also enriched in arsenic?

Although more analyses will strengthen this observation, our data show that there is a marked difference between the average As concentrations reported in pyrites versus pyrrhotites (Figure 5). Arsenic is enriched in Sw pyrites (mean 706 mg kg−1 As) and not enriched in Sw pyrrhotite (mean 1 mg kg−1 As) suggesting that As loss from metamorphic rocks occurs during de-sulfidation, a process also observed in meta-sedimentary rocks in New Zealand where the conversion of pyrite to pyrrhotite caused mobilization of metals and metalloids including As (Large et al., 2012). Additionally, the only significant difference in mean whole rock As concentrations found between different metamorphic grades in the present study was found between the low grade Sw and the high grade Sw rocks where As concentrations were shown to significantly decrease between the low and high grades concurrent with a S decrease. Taken together, new data reported here support Ferry’s (1981) proposed de-sulfidation reactions, with the simultaneous loss of As noted.

5.3 Non-Sulfide Arsenic Host Minerals

If pyrite decreases with increasing metamorphic grade and arsenic is not incorporated into pyrrhotite, where does the arsenic go? Volatilization from the metamorphic fluid is possible (Pitcairn et al., 2010) as is redistribution into other host rocks and minerals. Ferry (1981) notes a close association between de-sulfidation progression and the formation of biotite. Other studies show the existence of a pyrite:pyrrhotite transition in conjunction with the biotite isograd (Carpenter, 1974). The concurrent association between arsenic loss from pyrite as biotite forms suggests that As incorporation in biotite should be further investigated. Enrichment of As in biotite separated from Bengal basin Holocene aquifer sediments has been reported (Seddique et al., 2008). However, the mechanism by which arsenic is incorporated into the biotite structure in meta-sedimentary rocks in central Maine requires further investigation. Recent studies have illustrated the sites in silicate mineral structures that arsenic can occupy. For example, Hattori et al. (2005) proposed that As (V) substitutes for Si (IV) in the tetrahedral site of the silicate mineral antigorite, and Charnock et al. (2007) proposed As (V) substitution in the tetrahedral structure of garnet, which is another dominant mineral in the medium and high grade rocks of the Sw. Further investigation into arsenic-silicate mineral associations using mineral specific analysis techniques (laser ablation and XAS) are in progress (O’Shea et al., in prep.).

5.4 Arsenic Association with Secondary Minerals

Secondary minerals formed as weathering products of arsenic sulfide host minerals could also be associated with arsenic and many samples show clear signs of recent alteration (Figure 2a) which could be iron sulfates or iron oxide secondary minerals. More samples showed As release via oxidation than via reduction, and oxidative As was typically an order of magnitude greater than reduced As (Figure 3). This suggests that only minor concentrations of As are associated with iron or manganese oxide secondary minerals, although we caution that we selectively removed the weathered portion of rocks. Nevertheless, Fe enrichment on the edge of a pyrite megacryst (SEM image not shown) and surface alteration (Figure 2a) likely indicates localized weathering (since retrograde reactions are not observed in the study area) and yet arsenic enrichment on grain boundaries was not clearly observed (Figure 4b). Amorphous iron oxides noted in voids and cracks in rocks (Figure 2c) are likely to dissolve in HNO3, releasing arsenic which may account for elevated As concentrations extracted from rocks where sulfur was not detected such as observed in R051. In the SOv arsenic concentrations extracted by HNO3 increase slightly from low to medium grades. This, plus a correlation between As and Mn (r=0.52) could indicate As association with Mn secondary minerals although Mn and As co-adsorption to mineral surfaces could also account for their coupled occurrence.

5.5 Implications for Arsenic-Impacted Bedrock Aquifers

Under optimal geochemical conditions arsenic in the source rock of bedrock aquifers can be released and pose an environmental exposure risk from arsenic in ground (drinking) water. Because arsenic is widely distributed in the northeastern USA (this issue) and the modes of solubilization are many it presents a challenge in identifying direct controls on arsenic solubility in heterogenous bedrock geology. The presence of multiple primary arsenic-host minerals further complicates things.

Several relationships are considered to highlight this complexity: first, elevated arsenic detected here in low-grade Sw rocks and associated with pyrite, for example, could indicate an oxidative control on elevated As in these groundwaters; a control that dissipates as arsenian pyrite decreases with increasing metamorphism towards the southwest. However, Yang et al., (2009) show a west to east spatial correlation for decreasing groundwater As but unfortunately the groundwaters in the low grade Sw and SOv rocks were not directly sampled as part of their study. Arsenian pyrite oxidation is implied as an arsenic mobilization mechanism in As-rich black shales from Vermont by Ryan et al. (2013). Strong correlations among Fe, SO4 and As in groundwater were observed. Similarly, Lipfert et al., (2007) used isotopes of oxygen and sulfur to imply arsenic release by the anaerobic oxidation of sulfide minerals in the fractured bedrock aquifer of Northport, Maine. A redox control on arsenic release is also suggested by Yang et al., (2012) for the medium and high grade rocks of Sw and SOv where As is mobilized under low dissolved oxygen and high pH groundwater conditions but do not correlate with either Fe or SO4 (Yang et al., 2012). This suggests a more complex mechanism of As mobilization and is consistent with multiple As host minerals changing with progressive metamorphism where As-silicates are proposed as possible host minerals. Secondary Fe or Mn minerals in fractures likely contribute to As distribution in groundwater via pH-influenced desorption or reductive dissolution (Yang et al., this issue). Probably many of these phases are unstable, and also exist as some form of grain coatings but could be derived from the weathering of As-primary minerals in these metamorphic rocks.

Challenges in identifying multiple As-host minerals and multiple As-solubilization mechanisms were also encountered in the Mesozoic Basins by Serfes et al., (2005), and have been issues in other complex metamorphic terranes also, as presented by Verplanck et al., (2008). The wide variety of potential hosts, and their degree of stability and leachability, are all variables that may confound efforts to understand the distribution of elevated arsenic occurrence in groundwater.

One pattern that does agree with both bedrock and groundwater As data exists when comparing the two geologic units studied herein. Ayotte et al. (2003) were among the first to report elevated As concentrations in groundwater flowing through predominantly calcareous metamorphic rocks (including the Sw and SOv) in Eastern New England. Consistent with our results indicating the Sw bedrock is more enriched in As than the SOv Yang et al. (2009) report a higher incidence of elevated As in the Sw groundwater compared to the SOv (Sw: mean As 14.4 ug L−1, probability well water >10 ug L−1 39% compared to SOv: mean As 10 ug L−1, probability well water >10 ug L−1 24%) supporting the link between As abundance in groundwater and the geogenic nature of As occurrence in the bedrock aquifers of this region.

5.6 Arsenic and the Tectonic Cycle

In the meta-sedimentary belt of the Otago and Alpine schists in New Zealand Pitcairn et al., (2010) similarly report a loss of As (up to 14,000 mg kg−1 to non-detectable levels) as prograde metamorphism converted pyrite to pyrrhotite with increasing metamorphic grade. The same process is proposed for rocks in Central Maine and for other low grade rocks in Western New England (Ryan et al., this issue) where depletion of As from meta-pelites tends to occur at similar metamorphic mineral transitions found here; notably the chlorite to biotite isograd and concurrent decrease in pyrite abundance. The high solubility of arsenic allows it to be preferentially enriched in melts and crustal fluids rather than crystallized into mineral phases during initial metamorphic and dehydration reactions (Deschamps et al., 2013) and therefore highlights the importance of considering large scale fluid flow influenced by tectonic processes when identifying risks of As exposure via ground (drinking) water. Mukherjee et al., (in press.) agree by noting many As-impacted sedimentary basins are comprised of material derived from the weathering of adjoining major orogenic belts. Hydrothermal fluids conducive to As solubility occur in rift and shear zones too, further implicating the relationship between As occurrence in bedrock and tectonic processes. On a global scale, Amini et al., (2008) noted that the geologic variables used in their model to predict global geogenic As groundwater occurrences included an emphasis on young Holocene sediment, which may explain why their model under-estimates As contamination existing in the metamorphic bedrock aquifers of southern New Hampshire and Maine. The study herein suggests that meta-sedimentary rocks with anoxic marine sediment as protolith may be a reasonably important arsenic source to groundwater, but it is also plausible that non-pelitic protoliths host arsenic enriched primary minerals potentially derived from metamorphic fluid. Thus, groundwater in metamorphic rocks can be at risk of arsenic enrichment not only locally, but also globally, and inclusion of such bedrock geology in risk assessments may improve the results of models predicting arsenic occurrences in groundwater globally.

6. CONCLUSION

In central Maine, enrichment of arsenic above previously published arsenic concentration data for meta-sedimentary rocks is most influenced by arsenian pyrite although the presence of multiple arsenic mineral hosts is implied. Despite these variations, the regional occurrence of arsenic in northeastern north America likely shares a common influence of arsenic-rich diagenetic pyrite deposited under marine anoxic conditions and can be followed by the redistribution of arsenic from pyrite to other host minerals, potentially into silicates, during metamorphism. However, arsenic distribution varies notably and is difficult to link directly to occurrence in groundwater. Additional heterogeneity in the lithology and fractures of the bedrock, plus the multiple groundwater flow paths in the fractured bedrock aquifers further complicate and possibly contribute to the spatially heterogeneous groundwater As distribution at local and regional scales. Improved knowledge of enrichment of arsenic in meta-sedimentary rocks and arsenic host minerals as demonstrated here implies that risk assessment of meta-sedimentary rocks formed in a similar tectonic environment is recommended before groundwater development for drinking water supply.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

○

Arsenic is enriched up to 138 mg kg−1 in meta-sedimentary rocks in central Maine.

-

○

Pyrite contains up to 1,944 mg kg−1 As in slates and phyllites.

-

○

Pyrite abundance decreases in schists and gneisses as pyrrhotite appears.

-

○

Arsenic is < 1 mg kg−1 in pyrrhotite.

-

○

arsenic minerals are possible hosts in schists and gneisses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Qiang Yang and Ashley MacLean for valuable assistance in the field and laboratory at CUNY; George Breit and Heather Lowers for conducting the electron microprobe analyses; and Kevin Stolzenbach for assistance in the laboratory at USD. Conversations with Lois Ongley helped to improve our understanding of the local field conditions and geology of Maine. O’Shea gratefully acknowledges financial support from the University of San Diego’s Faculty Research Grant program and an NIEHS grant 2 P42 ES10349 to Zheng. Work on this manuscript by O’Shea was conducted at the Geoscience Academics in the Northeast writing retreat funded by NSF Award Numbers 0620087 to Suzanne O’Connell and 0620101 to Mary Anne Holmes. This is LDEO contribution ####.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Amini M, Abbaspour KC, Berg M, Winkel L, Hug SJ, Hoehn E, Johnson CA. Statistical modeling of global geogenic arsenic contamination in groundwater. Environmental Science and Technology. 2008;42:3669–3675. doi: 10.1021/es702859e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnórsson S. Arsenic in surface- and up to 90°C ground waters in a basalt area, N-Iceland: processes controlling its mobility. Applied Geochemistry. 2003;18(9):1297–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Ayotte JD, Montgomery DL, Flanagan SM, Robinson KW. Arsenic in Groundwater in Eastern New England: Occurrence, Controls, and Human Health Implications. Environmental Science & Technology. 2003;37(10):2075–2083. doi: 10.1021/es026211g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya P, Welch AH, Ahmed KM, Jacks G, Naidu R. Arsenic in groundwater of sedimentary aquifers. Applied Geochemistry. 2004;19(2):163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle RW, Jonasson IR. The geochemistry of arsenic and its use as an indicator element in geochemical prospecting. Journal of Geochemical Exploration. 1973;2(3):251–296. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter RH. Pyrrhotite Isograd in Southeastern Tennessee and Southwestern North Carolina. Geological Society of America Bulletin. 1974;85(3):451–456. [Google Scholar]

- Charnock JM, Polya DA, Gault AG, Wogelius RA. Direct EXAFS evidence for incorporation of As5+ in the tetrahedral site of natural andraditic garnet. American Mineralogist. 2007;92(11):1856–1861. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Zheng Y, Mortlock R, van Geen A. Rapid multi-element analysis of groundwater by high-resolution inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;379:512–518. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-2618-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester R, Hughes MJ. A chemical technique for the separation of ferro-manganese minerals, carbonate minerals and adsorbed trace elements from pelagic sediments. Chemical Geology. 1967;2:249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps F, Godard M, Guillot S, Hattori K. Geochemistry of subduction zone serpentinites: A review. Lithos. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Ferry JM. Fluid interaction between granite and sediment during metamorphism, South-central Maine. American Journal of Science. 1978;278(8):1025–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Ferry JM. Petrology of graphitic sulfide-rich schists from south-central Maine: an example of desulfidation during prograde regional metamorphism. American Mineralogist. 1981;66:908–930. [Google Scholar]

- Ferry JM. A Comparative geochemical study of pelitic schists and metamorphosed carbonate rocks from south-central Maine, USA. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 1982;80(1):59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ferry JM. Mineral reactions and element migration during metamorphism of calcareous sediments from the Vassalboro Formation, south-central Maine. American Mineralogist. 1983a;68(3–4):334–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ferry JM. Regional metamorphism of the Vassalboro Formation, south-central Maine, USA: a case study of the role of fluid in metamorphic petrogenesis. Journal of the Geological Society. 1983b;140(4):551–576. [Google Scholar]

- Ferry JM. A Biotite Isograd in South-Central Maine, U.S.A.: Mineral Reactions, Fluid Transfer, and Heat Transfer. Journal of Petrology. 1984;25(4):871–893. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber MB, Lee RC, Hatch JR, Pashin JC, Treworgy J. Role of Large Scale Fluid-Flow in Subsurface Arsenic Enrichment. In: Welch AH, Stollenwerk KG, editors. Arsenic in Ground Water. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. pp. 127–164. [Google Scholar]

- Guillot S, Charlet L. Bengal arsenic, an archive of Himalaya orogeny and paleohydrology. Journal of Environmental Science & Health, Part A: Toxic/Hazardous Substances & Environmental Engineering. 2007;42(12):1785–1794. doi: 10.1080/10934520701566702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori KH, Guillot S. Volcanic fronts form as a consequence of serpentinite dehydration in the forearc mantle wedge. Geology. 2003;31(6):525–528. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori K, Takahashi Y, Guillot S, Johanson B. Occurrence of arsenic (V) in forearc mantle serpentinites based on X-ray absorption spectroscopy study. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2005;69(23):5585–5596. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JP, Staal CR, van Miller BV. Links among Carolinia, Avalonia, and Ganderia in the Appalachian peri-Gondwanan realm. Geological Society of America Special Papers. 2007;433:291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JP, van Staal CR, Rankin DW. Comparative analysis of the geological evolution of the northern and southern Appalachian orogen: Late Ordovician-Permian. From Rodinia to Pangea: The Lithotectonic Record of the Appalachian Region. 2010:51–71. Geological Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Horton TW, Becker JA, Craw D, Koons PO, Chamberlain CP. Hydrothermal arsenic enrichment in an active mountain belt: Southern Alps, New Zealand. Chemical Geology. 2001;177(3–4):323–339. [Google Scholar]

- Large RR, Halpin JA, Danyushevsky LV, Maslennikov VV, Bull SW, Long JA, Gregory DD, Lounejeva E, Lyons TW, Sack PJ, McGoldrick PJ, Calver CR. Trace element content of sedimentary pyrite as a new proxy for deep-time ocean-atmosphere evolution. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2014;389:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Large R, Thomas H, Craw D, Henne A, Henderson S. Diagenetic pyrite as a source for metals in orogenic gold deposits, Otago Schist, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 2012;55(2):137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lipfert G, Sidle WC, Reeve AS, Ayuso RA, Boyce AJ. High arsenic concentrations and enriched sulfur and oxygen isotopes in a fractured- bedrock ground-water system. Chemical Geology. 2007;242(3–4):385–399. [Google Scholar]

- Lowers HA, Breit GN, Foster AL, Whitney J, Yount J, Uddin MN, Muneem AA. Arsenic incorporation into authigenic pyrite, Bengal Basin sediment, Bangladesh. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2007;71(11):2699–2717. [Google Scholar]

- Mango H, Ryan P. Source of arsenic-bearing pyrite in southwestern Vermont: Sulfur isotope evidence. Science of the Total Environment. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.03.072. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvinney RG, West DP, Grover TW, Berry HN. A stratigraphic review of the Vassalboro Group in a portion of central Maine. In: Gerbi C, Yates M, Kelley A, Lux D, editors. New England Intercollegiate Geological Conference Guidebook for Fieldtrips in Coastal and Interior Maine. 2010. pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Meranger JC, Subramanian KS, McCurdy RF. Arsenic in Nova Scotian groundwater. Science of The Total Environment. 1984;39(1–2):49–55. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(84)90023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Fryar AE, O’Shea BM. Major Occurrences of Elevated Arsenic in Groundwater and Other Natural Waters. In: Henke K, editor. Arsenic. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. pp. 303–350. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Verma S, Gupta S, Henke KR, Bhattacharya P. Influence of tectonics, sedimentation and aqueous flow cycles on the origin of global groundwater arsenic: Paradigms from three continents. Journal of Hydrology. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Osberg PH. An equilibrium model for Buchan-type metamorphic rocks, south-central Maine. American Mineralogist. 1971;56:570–586. [Google Scholar]

- Peters SC. Arsenic in groundwaters in the Northern Appalachian Mountain belt: A review of patterns and processes. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology. 2008;99(1–4):8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jconhyd.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters SC, Burkert L. The occurrence and geochemistry of arsenic in groundwaters of the Newark basin of Pennsylvania. Applied Geochemistry. 2008;23(1):85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pitcairn IK, Olivo GR, Teagle DAH, Craw D. Sulfide Evolution During Prograde Metamorphism of the Otago and Alpine Schists, New Zealand. The Canadian Mineralogist. 2010;48(5):1267–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Rango T, Bianchini G, Beccaluva L, Tassinari R. Geochemistry and water quality assessment of central Main Ethiopian Rift natural waters with emphasis on source and occurrence of fluoride and arsenic. Journal of African Earth Sciences. 2010;57(5):479–491. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnick RL, Gao S. Editors-in-Chief. 3.01 - Composition of the Continental Crust. In: Holland Heinrich D, Turekian Karl K, editors. Treatise on Geochemistry. Oxford: Pergamon; 2003. pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan PC, Kim JJ, Mango H, Hattori K, Thompson A. Dissolved Arsenic in a Fractured Slate Aquifer System, New England, USA: Influence of Bedrock Geochemistry, Groundwater Flow Paths, Redox and Ion Exchange. Applied Geochemistry. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P, West DP, Hattori K, Studwell S, Allen DN, Kim J. The influence of metamorphic grade on arsenic in metasedimentary bedrock aquifers: A case study from western New England, USA. Science of the Total Environment. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.05.021. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage KS, Tingle TN, O’Day PA, Waychunas GA, Bird DK. Arsenic speciation in pyrite and secondary weathering phases, Mother Lode Gold District, Tuolumne County, California. Applied Geochemistry. 2000;15(8):1219–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Seddique AA, Masuda H, Mitamura M, Shinoda K, Yamanaka T, Itai T, Biswas DK. Arsenic release from biotite into a Holocene groundwater aquifer in Bangladesh. Applied Geochemistry. 2008;23(8):2236–2248. [Google Scholar]

- Serfes ME, Spayd SE, Herman GC. Advances in Arsenic Research. Vol. 915. American Chemical Society; 2005. Arsenic Occurrence, Sources, Mobilization, and Transport in Groundwater in the Newark Basin of New Jersey; pp. 175–190. (Vols. 1-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sigfusson B, Gislason SR, Meharg AA. A field and reactive transport model study of arsenic in a basaltic rock aquifer. Applied Geochemistry. 2011;26(4):553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley P, Kinniburgh D. A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters. Applied Geochemistry. 2002;17(5):517–568. [Google Scholar]

- Tabelin CB, Igarashi T, Tamoto S, Takahashi R. The roles of pyrite and calcite in the mobilization of arsenic and lead from hydrothermally altered rocks excavated in Hokkaido, Japan. Journal of Geochemical Exploration. 2012:119–120. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tessier A, Campbell PGC, Bisson M. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. Analytical Chemistry. 1979;51(7):844–851. [Google Scholar]

- Verplanck PL, Mueller SH, Goldfarb RJ, Nordstrom DK, Youcha EK. Geochemical controls of elevated arsenic concentrations in groundwater, Ester Dome, Fairbanks district, Alaska. Chemical Geology. 2008;255(1/2):160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Jung HB, Culbertson CW, Marvinney RG, Loiselle MC, Locke DB, Cheek H, Thibodeau H, Zheng Y. Spatial Pattern of Groundwater Arsenic Occurrence and Association with Bedrock Geology in Greater Augusta, Maine. Environmental Science & Technology. 2009;43(8):2714–2719. doi: 10.1021/es803141m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Jung HB, Marvinney RG, Culbertson CW, Zheng Y. Can Arsenic Occurrence Rates in Bedrock Aquifers Be Predicted? Environmental Science & Technology. 2012;46(4):2080–2087. doi: 10.1021/es203793x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Culbertson C, Nielsen M, Schalk C, Johnson C, Marvinney RG, Stute M, Zheng Y. Flow and sorption controls of groundwater arsenic in individual boreholes from bedrock aquifers in central Maine, USA. Science of the Total Environment. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.04.089. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.