Summary

Of the hamstring muscle group the biceps femoris muscle is the most commonly injured muscle in sports requiring interval sprinting. The reason for this observation is unknown.

The objective of this study was to calculate the forces of all three hamstring muscles, relative to each other, during a lengthening contraction to assess for any differences that may help explain the biceps femoris predilection for injury during interval sprinting. To calculate the displacement of each individual hamstring muscle previously performed studies on cadaveric anatomical data and hamstring kinematics during sprinting were used. From these displacement calculations for each individual hamstring muscle physical principles were then used to deduce the proportion of force exerted by each individual hamstring muscle during a lengthening muscle contraction. These deductions demonstrate that the biceps femoris muscle is required to exert proportionally more force in a lengthening muscle contraction relative to the semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles primarily as a consequence of having to lengthen over a greater distance within the same time frame. It is hypothesized that this property maybe a factor in the known observation of the increased susceptibility of the biceps femoris muscle to injury during repeated sprints where recurrent higher force is required.

Keywords: biceps femoris, force, hamstring, injury, muscle, physics

Introduction

Hamstring strain injuries are common in sports that require sprinting such as soccer1, rugby union2, track and field3 and Australian football4. For hamstring injuries in sprinting sports, the location of the injury is most commonly in the long head of the biceps femoris muscle3–6. This contrasts to hamstring injuries in dancers, in whom the semimembranosus muscle is the most common hamstring muscle injured7.

The reasons for the predominance of biceps femoris muscle injuries in sprinting, compared to the less frequently injured semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles, is not understood. Postulated theories for this observation for the predominance for biceps femoris muscle injuries in sprinting include unique dual neural innervation of the biceps muscle8, different hip and knee flexion angles of the biceps femoris muscles compared to the other hamstring muscles9, hamstring length changes influenced by postural considerations10, more Type II fibres in the biceps femoris muscle compared to the other ham-string mucles11. None of these hypotheses have been substantiated scientifically12.

A previous study developed an experimental human kinematic model along with a musculoskeletal model to estimate hamstring lengths during treadmill sprinting and demonstrated that the change of length of the biceps femoris muscle was greater than the other two hamstring muscles13. This was considered to be, at least in part, a result of the lateral insertion of the biceps femoris14. A more recent study demonstrated that the biceps femoris muscle is subjected to more strain (where strain is defined as the ratio of the change in length to the original resting length) than the other two hamstring muscles15. The change in length (stretch) of each hamstring muscle is independent of running speed13, but as running speed increases, the calculated maximal hamstring force increases16 without any change in maximal hamstring length16. The maximum hamstring length occurs during the late swing phase of the gait cycle13,17, and in jumping18 and this is considered to result in maximal hamstring muscle work during this lengthening (eccentric) contraction phase19, which may also be a factor in hamstring muscle injuries20. Although these studies have given us valuable information on the kinematics of the hamstring muscles, it is still unclear how these factors relate to the observation that the biceps femoris muscle is more susceptible to injury than the semimembranosus or semitendinosus muscles during sprinting locomotion. This partly arises from an inability to reliably attribute the contributions of individual hamstring muscles to the total force produced by the hamstring muscle unit.

Accordingly, the aim of the current study is to utilise the available anatomical and kinematic analysis of hamstring muscle structure and function to numerically calculate change in length during an eccentric contraction of individual hamstring muscles, and to construct a simulated simplistic model of the human hamstrings. Using these calculations and applying physical principles, the force production of each individual hamstring muscle, relative to the other ham-string muscles, during an eccentric hamstring contraction can be deduced.

Method

This study was performed adhering to the Ethical Standards required by the journal21.

Numerical values for each individual hamstring muscle length, including the proximal and distal free tendon ends, were derived from a cadaveric study of the human hamstring muscles22. The anatomical length data (Tab. 1)22 was combined with the percentage stretch of individual hamstring muscles beyond their nominal resting length calculated from a previous study (Tab. 2)13 to calculate a numerical change in length (displacement) during a lengthening (eccentric) contraction. To calculate the total displacement, we used the entire individual hamstring muscle length from proximal bone tendon attachment to distal bone tendon attachment (thereby including the free tendon ends).

Table 1.

Cadaveric length of hamstring muscles.

| Muscle | Proximal Tendon Length (cm) | Muscle Length (cm) | Distal Tendon Length (cm) | Total (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semimembranosus | 11.1 | 26.4 | 6.8 | 44.3 |

| Semitendinosus | 1.2 | 31.6 | 11.1 | 43.9 |

| Biceps Femoris | 6.5 | 28.1 | 9.2 | 43.8 |

Muscle length, Proximal Tendon and Distal Tendon Length and Total Length (Ref Woodley and Mercer)20.

Table 2.

Stretch of hamstring muscles.

| Muscle | Stretch | Calculated change in length | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semimembranosus | 7.4% | =44.3*0.074 | 3.28 cm |

| Semitendinosus | 8.1% | =43.9*0.081 | 3.56 cm |

| Biceps Femoris | 9.5% | =43.8*0.095 | 4.16 cm |

Average stretch of each individual hamstring muscle during a lengthening contraction during treadmill sprinting total (Ref Thelen et al.)13.

To calculate forces on individual hamstring muscles, a model must be employed. In this study we have chosen to represent individual hamstring muscles as springs. A previous study13 that showed muscular change in length is independent of running speed. This infers that the displacement of the hamstring muscles can be considered constant, but as locomotive speed increases, the number of fibres recruited increases, allowing the muscle to produce more force. If we consider a single speed only, we can assume a constant number of fibres (although not necessarily the same fibres on each contraction) have been recruited for each hamstring muscle, and thus this idealised muscle can be represented as a spring. Using the laws of elastic spring motion, the force (F) produced by the hamstring muscles is proportional to displacement (x). It follows that the muscle which displaces least (in the case of the hamstring muscles, the one that lengthens least) is the muscle that exerts the least force (smaller x, smaller F). Defining this as the standard, we can then calculate the force of the other hamstring muscles relative to this least displaced (lengthened) muscle. In this manner, we calculate the relative forces between the three muscles, assuming that each muscle has an identical spring constant.

Finally using the anatomical length data combining with the displacement of each individual hamstring muscle we demonstrate the contraction of hamstring muscles with a simplistic working model scaled both to length and displacement using the object based Interactive PhysicsTM (Design Simulation Technologies, Canton, Michigan, USA) software.

Results

Table 1 shows the cadaveric anatomical hamstring muscle length data from free tendon end proximally to free tendon end distally. Table 2 shows the percentage stretch of each of the hamstring muscles. Combining the results of Table 1 and Table 2 we have calculated the length change (displacement) of each individual hamstring muscle (Tab. 2). This demonstrates the displacement of the semimembranosus muscle is the smallest of the three hamstring muscles. As force is proportional to displacement, and using the calculated force of the semimembranosus as standard, the force of the other hamstring muscles relative to the semimembranosus can be deduced (Tab. 3). As the biceps femoris muscle displaces (lengthens) further than the other two hamstring muscles, it must also produce more force than the other two hamstring muscles in a lengthening contraction. In relation to the semimembranosus muscle the biceps femoris muscle exerts 1.28 times relative more force for an assumed same spring constant.

Table 3.

Calculated forces of each hamstring muscle relative to semimembranosus muscle.

| Muscle | ||

|---|---|---|

| Semimembranosus | F(SM)=3.28/3.28 | 1.0 F(SM) |

| Semitendinosus | F(ST) =3.55/3.28 | 1.08 F(SM) |

| Biceps Femoris | F(BF) = 4.16/3.28 | 1.27 F(SM) |

F=Force, SM=Semimembranosus, ST=Semitendinosus, BF=Biceps Femoris

[Force = Change in Length of muscle divided by the Change in Length of least displaced muscle (Semimembranosus) derived from Table 2]

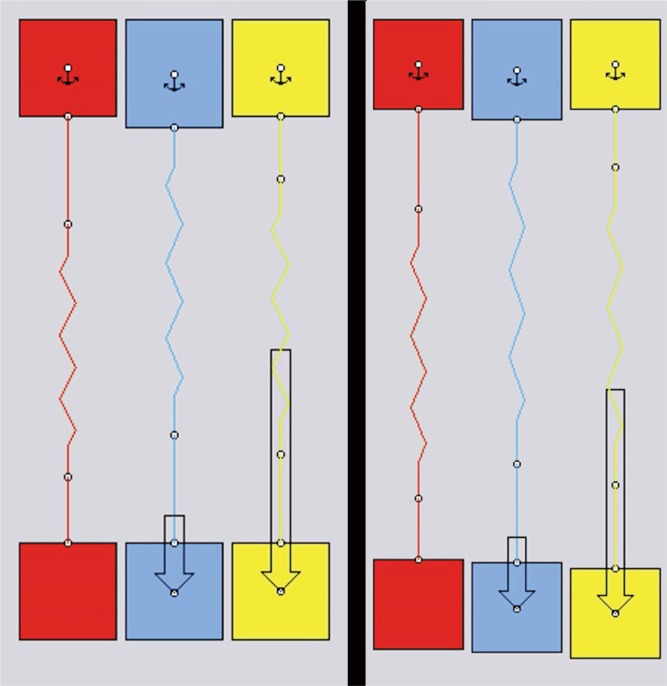

Hamstring muscle at rest in comparison scaled to length and displacement at full lengthening contraction (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Length and displacement of hamstring muscles during a lengthening contraction.

At rest (Left of Figure) and at full displacement (Right of Figure). Scaled to actual length of each muscle and subsequent displacement during a lengthening contraction.

Red Semimembranosus, Blue Semi-tendinosus, Yellow Biceps.

Straight lines represent tendon, Bent line represents muscles, Blocks represent bone.

In a recent study (Ref Ward et al.)40 where 21 cadavers were dissected the authors measured muscle length that was defined from tendon muscle fibre proximal to distal that did not include free tendon ends the lengths were biceps 34.7 cm ± 3.7, semitendinosus 29.7 cm ± 3.9, semi-membranosus 29.3 cm ± 3.4. Thus on these calculations the differentials of the force would be 1.0 SM, 1.11 ST and 1.52 BF. Again if you calculated on the extremes of the standard deviation for semimembranosus and biceps femoris (maximum length SM, minimum length BF) BF calculation is still 1.20 F(SM).

Discussion

The biceps femoris muscle is required to exert more force, relative to the other two hamstring muscles, during a lengthening muscle contraction. It is important to remember that our force calculations arise from change in length data only, and do not attempt to assign spring constant values to the individual hamstring muscles. How this finding contributes to the observation that the biceps femoris is more susceptible to injury in sprinting conditions when compared to the other two hamstring muscles requires some speculation.

Current knowledge demonstrates that: 1) in sports requiring repeated sprinting the biceps femoris muscle is the most common hamstring muscle injured4–6,12; 2) the part of contraction (gait) cycle where the maximum hamstring force production occurs is the lengthening (eccentric) phase16; 3) ham-string force production increases as running speed increases16. The eccentric phase of a sprinting athlete has been considered to be the time of risk for muscle injury15–17, generally resulting in injury to the biceps femoris muscle of the hamstring. Thus in a sprinting athlete as running speed increases there is a requirement during hamstring lengthening for hamstring increased force production to counter, acting as a brake, the propulsion contraction principally of the hip flexors and quadriceps muscles. The findings of this study demonstrate that the biceps femoris muscle requires proportionally higher force production needed for normal operation (lengthening contraction). Therefore if circumstances exist where overall muscle force production may be impaired it is reasonable to suggest that the biceps femoris muscle would be more affected than the other two hamstring muscles.

Force production in muscles is impaired in fatigued muscles compared to non-fatigued muscles23. Observations in sports involving interval sprinting have also demonstrated fatigue as a significant risk factor for hamstring muscle strain injuries, with a predominance of injuries occurring late in both halves of soccer24,25 and rugby union2 matches, and in the later stages of Australian football matches4.

In a similar manner the semitendinosus muscle is required to exert more force, that is, it displaces further, when compared to the semimembranosus muscle, thereby increasing its susceptibility when comparing the properties of these two muscles in sprinting injuries. Again, hamstring injury imaging studies confirm this proposition, with the semitendinosus muscle being the second most common hamstring muscle injured in sports requiring interval sprinting4–6, with the semimembranosus being the least commonly injured4–6.

The actual mechanism of muscle injury in the case of a fatigue-associated sprinting injury is not presently known. However, it is not likely to be a simple over-stretch which has been proposed for the semimembranosus muscle stretch injury seen in dancers7. An alternative theory for mechanism for biceps femoris injury is where there is a failure at the musculotendinous junction (the region of muscle injury in stretch/strain6,25) given inadequate force production with the lengthening tendon in effect shearing away from the inadequately contracting (lengthening) muscle.

Muscles acting as springs – movement

The major assumption of this article is that the ham-string muscles have spring like properties thus allowing the use of the laws governing elastic spring motion. A property of springs is that peak lengthening velocity is reached before maximum length, with velocity being zero when the spring reverses direction at its maximum length26,27. Human hamstring muscle contraction demonstrates these properties having pek velocity before maximal lengthening occurs and reversing direction after the late swing phase of the gait cycle13 there by returning to its original length during the concentric muscle phase. Before the lengthening of the muscle (or spring) at the resting position it is assumed that the net force on the tendon attachments (spring ends) is zero. In addition if the tendons stretch, the muscles eccentrically contract (spring elongates) the muscle (spring) exerts a force on the attachments which acts in the direction of returning the spring back to its natural length27–30. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that, with respect to movement, muscles can be considered in many respects to act as springs31.

Activation of muscles – Muscles acting as springs – Independent muscle action

Unlike non biological tissues, muscle springs can produce mechanical energy30 through muscle activation that is in part neurally mediated. In skeletal muscle, this allows movement energy to be temporarily stored in a tendon and then released to do work on a muscle that is actively lengthened to absorb energy30. Although human hamstring muscles act in a unified fashion, almost certainly because of their different architecture the actual timing of each muscle contraction (activation) would vary between the three ham-string muscles and probably contributes to the nonlinear muscle action (see below). This probably reflects slightly different functions for the three ham-string muscles. Despite this, there is a turnaround point for all three hamstring muscles – end of the eccentric phase of the contraction – where the muscle begin to shorten and again this property is identical to a spring system.

Laws of spring motion in relation to non-linear muscle action

For the laws of spring motion to be relevant then the spring must work within its elastic limit. When a material breaks or deforms irreversibly it is no longer working within its elastic limit and hence motion will not conform to the laws of spring motion. The original laws of spring motion were devised by Hooke’s Law, F=kx26 (where F is the magnitude of the restoring force, x is the displacement, and k is the spring constant). Thus for a given spring constant force is proportional to displacement. However it has been demonstrated that muscle action is non-linear29,30. In a recent study on muscle motion (in the ballistic prey capture mechanism in toads) a formula was devised that predicted that the displacement of the muscle spring as function of the change of force28.

[x= displacement, ΔF = change in force. The shape of the exponential (non-linear) function is described by two constants c1 and c2 with the spring constant of muscle k being the first derivative of the inverse of the above equation]27.

Another recent experiment demonstrates that, for a wide range of muscles over a wide range of species, these constants c1 and c2 remain relatively unchanged32. Hence, considering this in non-linear muscle action, by rearranging the equation, force F will be proportional to the log function of the displacement x.

When studies have compared linear motion to nonlinear motion of muscles values are not significantly different33,34. Most studies that calculate non-linear summation of force in motor units is probably irrelevant in understanding muscle function35. Thus we feel justified in our example of classifying force change for hamstrings as being proportional to displacement for non-linear (and linear) muscle contraction.

Muscles acting as springs – Spring constant

The spring constant of each individual hamstring muscle would be affected by muscle density, mass, architecture (pennation), cross-sectional area and the muscles inherent length – tension relationship. Therefore, it is unlikely (and probably impossible) that the (k) spring constant would be identical for each individual hamstring muscle as we have assumed in our study. However a significant dilemma currently exists – it has not been possible to obtain accurate spring constants for the hamstring muscles, thus hampering exact individual hamstring force calculations with the reverse also being true, with an inability to obtain accurate individualised hamstring forces, thus hampering exact spring constant calculations. Thus, we rely on models such has been developed in this study to deduce possible reasons for muscle action and muscle failure, especially in the area of hamstring injuries where the pathogenesis is so poorly understood12.

Other study weaknesses

In calculating these relative force differentials, various other weaknesses are apparent. Firstly, the anatomical parameters that were used in this study were derived from only 6 elderly embalmed cadavers whose prior history of activity and functionality were unknown20. In addition this study did not include error calculations in their measurements and nor could they be calculated from the information provided in this study. This however is the only study to our knowledge that measures in an anatomical method the total muscle length including free tendon ends and thus we chose this study as being the most relevant to calculate our relative forces in the manner outlined in the present study.

Studies on the kinematics of sprinting13–18 have generally used the principles (a nonlinear optimization algorithm and anatomical constructs that subsequently developed the Open Sim model36, which does not use any direct measurements of entire hamstring length that includes the free tendon ends. This model calculates the length of the tendon (called the tendon slack length) from the assumed bony model, as the anatomical information is derived from five elderly embalmed cadavers37,38 that only measured the musculotendon length of the hamstring muscles. Also, in these studies the muscle forces are derived by assuming the muscles have uniform density, based on a study performed over 50 years ago39. A recent study on 21 cadavers40 calculated that the difference in muscle fibre lengths from the anatomical study37 used to construct the Open Sim model36 varied by 10–100%. In relation to the hamstring muscles that are used in the current kinematic analysis model, these were considerably shorter than the findings from this recent cadaver study40. Thus, the accuracy of the Open Sim model itself has been called into doubt40. The likely consequence of this is that calculation of the actual forces of the hamstring muscles presented in all studies must be considered relative to the anatomical model parameters. Two recent studies calculated that the force production in an eccentric contraction was maximal in the semimembranosus muscle, compared to the other two hamstring muscles15–16. This finding is not surprising, as the semimembranosus has the shortest fibre length, largest physiological cross-sectional area and largest mass of the three hamstring muscles22, all features generally considered advantageous with respect to force production41. Our study does not conflict with this finding, as we calculate the individual forces of the hamstring muscles relative only to their displacement. Although not part of this study it can also be calculated that, if the semimembranosus exerts the most total force but displaces the least, then this muscle probably has the highest spring constant. In other words, the semimembranosus is the stiffest muscle. This may explain why the semimembranosus is the most likely injured muscle in a simple over-stretch injury such as seen in dancers and water skiers7,42.

For measurements of change in length, we have used the percentage change of length as calculated in a kinematic sprinting study13. However, it must be stated that in this study the authors normalized the length of the hamstring muscle to a value that was not defined. Thus, the percentage stretch figures we have used may also not be accurate. In defence of this study13 the percentage length changes of the three muscles biceps, semimembranosus and semitendinosus were highly consistent at different running speeds (less than 1% difference) and with limited standard deviation (less than on average for all three muscles of 0.2%) and thus considering 14 athletes were tested makes there percentage length changes conclusions valid. In addition other studies have demonstrated that the biceps femoris muscle exhibits a greater change in length15,16 compared to the other two hamstring muscles. In this way, the principle of the biceps femoris muscle displacing more than the other two hamstring muscles is consistent across relevant studies. This implies that, even though the actual displaced length used in the present investigation may be somewhat incorrect, the principle of the biceps femoris exerting more force in relative terms compared to the other two hamstring muscles will be upheld.

Finally, the present study specifically did not include the short head of the biceps as a separate hamstring muscle in our hamstring modelling: this can be considered another weakness. In terms of evolution and anatomical development, it is considered that the short head of the biceps, with its different innervation, has migrated from originally being a flexor of the hip joint to its current action of assisting the ham-string muscles in extending the leg43. It is postulated this has evolved over time to assist in force production for the long head of biceps in the bipedal human animal.

Until further research is completed, only theoretical applications on the value of the findings of this study can be applied. One such application would be that, as the biceps femoris is more susceptible to injury because it exerts more force to complete a longer stretch in the same amount of time than either the semimembranosus or semitendinosus muscles, it seems feasible to suggest that, if these other muscles of the hamstring group could be trained to stretch further during hamstring action then the biceps would require less force to sustain eccentric muscle action. This application might have relevance when the total postural/muscle factors including gluteal muscles and lower lumbar spine can be appropriately assessed and acted upon. Finally, enhancing fatigue resistance by training may also be a fruitful area in preventing hamstring injuries. This has been the basis of some in the field hamstring injury prevention programs44,45.

Conclusion

As the biceps femoris muscle displaces (stretches) more than either the semimembranosus or semitendinosus muscles during a lengthening muscle contraction, it is required to relatively exert more force. This may be a factor in the known observation of the increased susceptibility of the biceps femoris muscle of the three hamstring muscles to injury where recurrent higher force is required, such as in sports that require repeated sprinting.

References

- 1.Arnason A, Sigurdsson SB, Gudmundsson A, Holme I, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Risk Factors for Injuries in Football. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(1S):5S–16S. doi: 10.1177/0363546503258912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks JH, Fuller CW, Kemp SP, Reddin DB. Incidence, Risk and Prevention of Hamsting injury in professional rugby union. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(8):1297–1306. doi: 10.1177/0363546505286022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during high speed running: a longitudinal study using clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):197–206. doi: 10.1177/0363546506294679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP, Barnes PG, Fon GT. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Clinical Findings in 83 Athletes with Posterior Thigh Injury. Comparison of Clinical Findings with Magnetic Resonance Imaging Documentation of Hamstring Muscle Strain. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(6):969–973. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310063701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connell DA, Schneider-Kolsky ME, Hoving JL, et al. Longitudanal study comparing sonographic and MRI assessment of acute and healing hamstring injuries. AJR. 2004;183(4):975–984. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.4.1830975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slavotinek JP, Verrall GM, Fon GT. Hamstring Injury in Athletes: The Association between MR Measurements of the Extent of Muscle Injury and the Amount of Time Lost from Competition. AJR. 2002;179:1621–1628. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during slow-speed stretching: clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and recovery characteristics. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):197–206. doi: 10.1177/0363546507303563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkett LN. Investigation into hamstring strains: the case of the hybrid muscle. J Sports Med. 1975;3(5):228–231. doi: 10.1177/036354657500300504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chleboun GS, France AR, Crill MT, Braddock HK, Howell JN. In vivo measurement of fascicle length and pennation angle of the human biceps femoris muscle. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169(4):401–409. doi: 10.1159/000047908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gajdosik RL, Albert CR, Mitman JJ. Influence of hamstring length on the standing position and flexion range of motion of the pelvic angle, lumbar angle, and thoracic angle. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;20(4):213–219. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1994.20.4.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrett WE, Mumma M, Lucareche CL. Ultrastructural differences in human skeletal muscle fiber types. Orthop Clin North Am. 1983;14:431–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrett WE. Muscle strain injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(6):S2–S8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thelen DG, Chumanov ES, Hoerth DM, et al. Hamstring muscle kinematics during treadmill sprinting. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2005;37(1):108–114. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000150078.79120.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thelen DG, Chumanov ES, Best TM, Swanson SC, Heiderscheit BC. Simulation of biceps femoris musculotendon mechanics during the swing phase of sprinting. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2005;37(11):1931–1938. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000176674.42929.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schache AG, Dorn TW, Blanch PD, Brown NA, Pandy MG. Mechanics of the Human Hamstring Muscle during Sprinting. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(4):647–658. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318236a3d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chumanov ES, Heiderscheit BC, Thelen DG. The effect of speed and influence of individual muscles on hamstring mechanics during the swing phase of sprinting. J Biomech. 2007;40(16):3555–3562. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padulo J, Powell D, Milia R, Aedigo LP. A paradigm of uphill running. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padulo J, Tiloca A, Powell D, Granatelli G, Bianco A, Paoli A. EMG amplitude of the biceps femoris during jumping compared to landing movements. Springerplus . 2013;9(2):520. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schache AG, Kim HJ, Morgan DL, Pandy MG. Hamstring muscle forces prior to and immediately following an acute sprinting-related muscle strain injury. Gait Posture. 2010;32(1):136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chumanov ES, Heiderscheit BC, Thelen DG. Hamstring Musculotendon Dynamics during Stance and Swing Phases of High-Speed Running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(3):525–532. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181f23fe8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padulo J, Oliva F, Frizziero A, Maffulli N. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research. MLTJ. 2013;4:250–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodley SJ, Mercer SR. Hamstring muscles: architecture and innervation. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;179(3):1251–141. doi: 10.1159/000085004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mair S, Seaber A, Glisson R, Garrett WE. The role of fatigue in susceptibility to acute muscle strain injury. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(2):137–143. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Small K, McNaughton L, Greig M, Lovell R. The effects of multidirectional soccer-specific fatigue on markers of hamstring injury risk. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(1):120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrett WE., Jr Muscle strain injuries: clinical and basic aspects. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1990;22:436–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooke R. Micrographia: or some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses: with observations and inquiries thereupon. Printed for John Martyn, printer to the Royal Society; p. 1667. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindstedt SL, Reich TE, Keim P, et al. Do muscles function as adaptable locomotor springs? J Exp Biol. 2002;205(15):2211–2216. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.15.2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lappin AK, Monroy JA, Pilarski ED, Zepnewski ED, Pierotti DJ, Nishikawa KC. Storage and Recovery of elastic potential energy powers ballistic prey capture in toads. J Exper Biology. 2006;209:2535–2553. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monroy JA, Gilmore LA, Krebs AK, et al. Elastic properties of muscle during active shortening. Inter Comp Biol. 2006;46:e100. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts TJ, Azizi E. Flexible mechanisms: the diverse roles of biological springs in vertebrate movement. J Exper Biology. 2011;214:353–361. doi: 10.1242/jeb.038588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickinson MH, Farley CT, Full RJ, Koehl MAR, Kram R, Lehman S. How animals move: an integrative view. Science. 2000;288:100–106. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monroy JA, Lappin AK, Nishikawa KC. Elastic Properties of Active Muscle – On the rebound. Exer Sports Science Reviews. 2007;35(4):174–179. doi: 10.1097/jes.0b013e318156e0e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fusi L, Brunello E, Reconditi M, Piazzesi G, Lombardi V. The nonlinear elasticity of the muscle sarcomere and the compliance of myosin motors. J Physiol. 2014;592:1109–1118. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.265983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandercock TG. Non-linear Summation of Force in cat tibialis anterior: A muscle with intrafascicularly terminating fibres. J App Physiol. 2003;94:1955–1963. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00718.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandercock TG. Summation of Motor Unit Force in Passive and Active Muscle. Exer Sports Science Reviews. 2005;33(2):76–83. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200504000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delp SL, Anderson FC, Arnold AS, et al. OpenSim: open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54(11):1940–1950. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.901024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wickiewicz TL, Roy RR, Powell PL, Edgerton VR. Muscle Architecture of the Human Lower Limb. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(179):275–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friederich JA, Brand RA. Muscle fiber architecture in the human lower limb. J Biomech. 1990;23(1):91–95. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90373-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mendez J, Keyes A. Density and composition of mammalian muscle. Metabolism. 1960;9:184. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ward SR, Eng CM, Smallwood LH, Lieber RL. Are Current Measurements of Lower Extremity Muscle Architecture Accurate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(4):1074–1082. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0594-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lieber RL, Fridén J. Clinical significance of skeletal muscle architecture. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:1647–1666. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200011)23:11<1647::aid-mus1>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sallay PI, Friedman RL, Coogan PG, Garrett WE. Hamstring muscle injuries among water skiers. Functional outcome and prevention. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(2):130–136. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin BF. The origins of the hamstring muscles. J Anat. 1968;102(2):345–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Small K, McNaughton L, Greig M, Lovell R. Effect of timing of eccentric hamstring strengthening exercises during soccer training: implications for muscle fatigability. Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(4):1077–1083. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318194df5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP, Barnes PG. The effect of sports specific training on reducing the incidence of hamstring injuries in professional Australian Rules football players. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(6):363–368. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]