Summary

Background:

tendon tissue shows limited regeneration potential with formation of scar tissue and inferior mechanical properties. The capacity of several growth factors to improve the healing response and decrease scar formation is described in different preclinical studies. Besides the application of isolated growth factors, current research focuses on two further strategies to improve the healing response in tendon injuries: platelet rich plasma (PRP) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs).

Objective:

the present review focuses on these two options and describes their potential to improve tendon healing.

Results:

in vitro experiments and animal studies showed promising results for the use of PRP, however clinical controlled studies have shown a tendency of reduced pain related symptoms but no significant differences in overall clinical scores. On the other hand MSCs are not totally arrived in clinical use so that there is still a lack of randomized controlled trials. In basic research experiments they show an extraordinary paracrine activity, anti-inflammatory effect and the possibility to differentiate in tenocytes when different activating-factors are added.

Conclusion:

preclinical studies have shown promising results in improving tendon remodeling but the comparability of current literature is difficult due to different compositions. PRP and MSCs can act as efficient growth factor vehicles, however further studies should be performed in order to adequate investigate their clinical benefits in different tendon pathologies.

Keywords: tendon regeneration, regenerative medicine, growth factor carriers

This study meets the ethical standards of the journal1.

Introduction

Tendons play an essential role in the musculoskeletal system stabilizing joints and transmitting loads from muscle to bone. They show a limited regeneration potential due to their slow metabolism and limited blood supply.

During tendon healing, tenocytes produce large amounts of collagen III instead of collagen I2. This often results in the formation of scar tissue, representing disorganized matrix. Compared to intact tendon tissue scar tissue shows inferior mechanical properties3.

Research within the last two decades had focus in tendon healing. Studying the molecular mechanisms had revealed the presence of several growth factors which play an essential role in the tendon healing process. Recent therapies which deliver this growth factors to the healing site have shown promising results in order to improve tendon healing4–6.

Different in vitro and animal studies proved the capability of several growth factors to improve the healing response and decrease a disorganized repair7–9. However, until now, none of these approaches has reached clinical use in tendon repair. Furthermore, the optimal application technique is not solved yet. Recombinant growth factors show a very short half-life under physiological conditions. Thus sequential re-application is necessary to achieve sufficient growth factor levels during healing. This results in enormous costs and considerable burden for the patient.

Due to these unsolved problems regarding recombinant growth factors, researchers are presently focusing on alternative growth factor sources, namely platelet-rich plasma and autologous bone marrow concentrate. The present review focuses on both preparations and describes their potential to improve tendon healing. It points out the rationale of their use, reviews laboratory in vitro and in vivo results, regarding their effectiveness and gives an overview of clinical studies.

Growth Factors delivery methods

Platelet rich Plasma

Per definition the term platelet-rich plasma (PRP) describes a preparation obtained from peripheral blood with enrichment of the platelet fraction10.

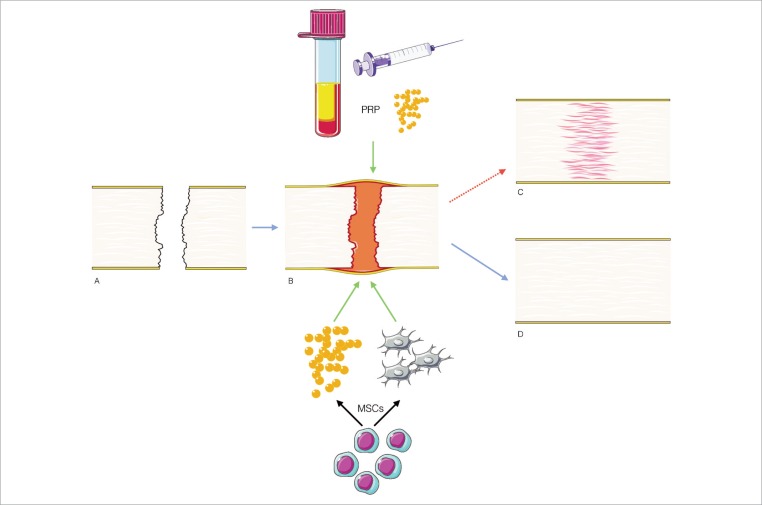

Platelets produce a number of relevant cytokines participating in physiological tendon healing: platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1)4,5,11,12,. In the early phase of tendon healing a key step is to increase vascularity supported by different factors13, including VEGF and HGF. These seem to act in a dose dependent response14. This early angiogenic effect is vital for tendon and ligament healing13. The rationale behind using PRP is to stimulate platelets to secrete these anabolic growth factors, they contain. This is achieved by their activation due to their enrichment during preparation15 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

After a tendon injury (A) an increasing number of inflammatory cells, platelets and erythrocytes migrate to the site of injury. (B) However the remodeling phase leads to scar tissue and decreased mechanical properties. (C) Current strategies to deliver GF in order to improve the healing of the tendon (D) by direct administration of a supra physiological concentration within the PRP or the capability of MSCs either to differentiate into tenocytes or paracrine release of GF.

GF: Growth factors; PRP: Platelet rich plasma; MSCs: Mesenchymal stem cells.

In vitro studies

PRP shows positive effects on tenocytes in vitro. On the one hand, it promotes cell proliferation8, on the other it enhances cell function and stimulates the synthesis of tendon matrix8. During tendon healing all cytokines have different peak concentrations over time, revealed in a rat rotator cuff tendon model4,5. One further key factor promoting tendon healing is IGF-1. In a rabbit Achilles tendon model a peek expression of IGF-1 was found at the second week of healing in different cells, but mainly in tenocytes5. In the early phase of tendon healing a key step is to increase vascularity supported by different factors13, including VEGF16,17 and Hepatic Growth Factor (HGF). These seem to act in a dose dependent response14 proven in vitro17,18, as well as in animal models13. This early angiogenic effect is vital for tendon and ligament healing13.

Furthermore, some studies even indicate, that PRP may protect tenocytes from impaired function caused by certain drugs19–21. Besides the reported positive effect of PRP on tenocytes, an additional antiinflammatory activity has been reported in several studies attributed to the HGF22–24. However, the anti-inflammatory mechanism is not clarified, yet. In development of tendinopathy and during tendon healing, inflammation seems to play a key role. Here, especially prostaglandin E2 seems to be a key factor25,26. In this context, the anti-inflammatory effect of PRP may contribute to an improved tendon regeneration.

In vitro studies suggest also that PRP by injection does not reverse degenerative conditions of tendinopathy27.

Animal studies

Positive effects of PRP were not only shown in vitro but also in animal models. In a rabbit patellar tendon model, the addition of PRP revealed increased cellular proliferation and collagen production, indicating a higher metabolic activity within the first days of tendon healing28. Achilles tendon bone junction shown improvement of the healing when morphogenetic protein 2 was added to PRP in a rabbit model29. Application of PRP resulted in superior orientation of collagen fibers and signs of increased metabolic activity in a defect model of the superficial digital flexor tendon in horses. This was also combined with a higher load to failure30. Beck et al. found significant effects on mechanical properties in a rotator cuff rat model by augmentation with PRP in comparison to a control group31. Here, improved tendon continuity was observed in histological analysis.

In conclusion animal studies revealed a positive impact of PRP on the initial healing process32, tendon regeneration28–30 and mechanical properties29–31.

Human studies

Several under powered studies have reported favorable results by the use of PRP for different tendon injuries33–40. Several well structured clinical randomized controlled trials41–53 report no significant differences when PRP was compared to controls for the treatment of tendinopathy (elbow, achilles, rotator cuff, plantar fascia), rotator cuff and achilles tendon ruptures.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies for the treatment of painful tendinopathy, Andia et al. found improvement in pain related symptoms although the studies failed to prove superiority for the PRP administration54.

Limitations of use of PRP

To date there are several commercially available PRP systems9,15, 55, which differ among them in either the centrifugation method, platelet concentration, release rate of growth factors9,56,57, white58,59 and red blood cell concentration and/or activation60. Differences among PRP commercial presentations have not been clarified, regarding the optimal concentration of growth factors delivery and their effects on tendon regeneration.

Mesenchymal stem cells

Types and application of stem cells

Stem cells are certain cell types that are undifferentiated and inhere the ability to differentiate into different cell types. Stem cells can be found in all stages of individual development. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are only found in early developmental stages of the organism. They represent the only truly pluripotent cell type, having the ability to renew itself indefinitely. As a unique precursor cell, it can differentiate into cells of all three germ layers61. Besides the naturally occurring ESCs, researchers have demonstrated a way to dedifferentiate somatic cells into a pluripotent ESC-like status. To obtain these “induced pluripotent stem cells” (iPS) somatic cells are transfected with four embryonic transcription factors62. Even though ESC and iPS-cells showed promising potential in promoting tendon regeneration in preclinical studies they are far from being introduced into clinic63. Both cell types inhere significant cancerogenic potential64 and ethical concerns exist towards the use of ESCs. These facts presently forbid their introduction into clinical therapies. Thus, current stem cell based concepts focus on adult stem cells. These exist in nearly all tissues of the adult body, where they are responsible to maintain the tissues integrity by substituting dying cells. In terms of tendon healing, adult stem cells from mesenchymal tissues, the mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), are the most promising63. Mesenchymal stem cells are multipotent and inhere the ability to differentiate into all mesenchymal tissues, including tenocytes, osteoblasts, chondrocytes and fat cells65.

MSCs can contribute to tendon healing in different ways66. First, they can provide tenocytes by direct differentiation into these cells. Secondly, they can provide a number of anabolic cytokines by their extraordinary paracrine activity. Thirdly, they show significant anti-inflammatory activity that may contribute to the healing process63 (Fig. 1).

MSCs can be obtained from different sources27, 66, e.g. adipose tissue (AMSCs)67 or synovial tissue (SMSCs)68 or the most frequent used source bone marrow (BMSCs)69–74. Connective tissue progenitor cells had been obtained from humeral bone marrow during rotator cuff repair in an adequate number as well as in small numbers from synovium, subacromial bursa and supraspinatus tendon70,74.

MSCs can either be administrated by simple injection of a cell suspension (cell therapy approach), or they can be used together with biomaterials (tissue engineering approach)63. Here, aim of the cell therapy approach is to improve regeneration of damaged tendon tissue, as the tissue engineering approach provides new-formed tendon tissue to substitute lost tissue. This review will focus only on cell therapy approaches, as we consider tissue engineering should be discussed separately as a new and very broad topic.

In vitro studies - Mechanism of improving regeneration

Survivorship of MSCs after administration has been successfully proven by immunochemistry labeling75,76, and differentiation of MSCs into tenocyte-like cells has been proven by several authors77–82. Addition of different growth factors like BMP-1277,78, insulin79, or viral transduction of transcription scleraxis factor80 have successfully increased transcription of decorin80, tenmodulin77,80 and collagen I80,82, and successful tenogenic differentiation when a dense collagen matrix was used81.

Several studies revealed, that MSCs provide beneficial effects on damaged tissues without any detectable engraftment to the damaged tissue. Moreover, even protein extracts from MSCs and culture medium conditioned by MSCs could provide similar improvement in tissue function in models of liver disorders or heart ischemia, as application of MSCs83,84. Recent studies revealed, that these effects are mediated by the strong paracrine activity of MSCs. More and more researchers are convinced, that this paracrine stimulation of tissue regeneration is the most important mechanism of MSCs to contribute in tissue regeneration85. Cell proliferation, host cells protection and enhancement of angiogenesis could be attributed to this capability of MSCs to release paracrine factors like IGF-1, HGF, VEGF, IGF-2, bFGF, and pre-microRNAs86,87.

Besides their paracrine capacity they are hypoimmunogenic and prevent T cell response as well as induce an immunosuppressive local microenvironment88. Therefore they may be used for immunomodulating therapies a variety of diseases or local tissue disorders. Due to their hypoimmunogenic properties they may even be used in an allogenic transplantation-approach65,89.

In vitro studies have lead the scientific community to investigate capabilities of MSCs to improve tendon regeneration in vivo.

Animal studies

Several animal studies have shown the capability of MSCs to improve the tendon regeneration. Here, use of MSCs revealed particular impact on the early remodeling of the tendon-bone junction68,90. Regeneration of the enthesis due to MSC application was described by Nourissant et al. As they only found scar formation in the control group, a normal appearing enthesis regenerated in the MSCs group7. Comparable results were reported by Lim et al. who used coated tendon allografts with MSCs in a rabbit model, finding are sembling of the enthesis with cartilage in the intervening zone91. Here, formation of a zone of fibrocartilage blending developed on the bone to allograft surface92. Besides histologic improvement, application of MSCs can also enhance biomechanical properties of tendon to bone healing. This could be observed in different animal models71,72,75,91–96.

Application of MSCs may also have a positive impact on intratendinous healing. An improved regeneration after application of MSCs could be observed in a rat achilles tendon defect model in several studies95,97. Furthermore, Schnabel et al. revealed positive effects of autologous MSCs in tendinitis. Using an equine tendinitis model of the flexor digitorum superficialis, the authors demonstrated significant improvement in histology93.

Besides the potential benefits, application of MSCs may have on tendon and tendon to bone healing; some studies indicate, that MSCs may also have negative effects on regeneration. One problem in the use of MSCs is heterotopic bone formation98. Awad et al. used a collagen gel seeded with bone marrow MSCs to treat patella-tendon defects and after 26 weeks they found 28% of bone formations within the repair99. Tensile loading results in increased expression of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) from MSCs. This BMP2 enhances osteogenic differentiation of stem cells, providing a possible explanation for calcifying tendinopathy100. Also prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is increased by mechanical stimulation. High levels of PGE2 may enhance differentiation of MSCs into adipocytes and osteocytes, instead of tenocytes101.

Human studies

In general, application of autologous mesenchymal stem cells seems to be rather save. Up to now a significant number of patients were treated with autologous MSCs for various pathologies. Here, no severe complications, as cancerogenicy, were reported in the literature63. Centeno et al. investigated patients treated with ultra-expanded, autologous BMSCs, due to different orthopedic diseases. 3 cases of complication (increased swelling, pain and joint effusion) were labeled as “possible” side effect due to MSC treatment. However all of them were self-limited or regredient by conservative treatment. The study demonstrated no evidence of neoplastic complications, monitored with high field MRI tracking102.

However until now there are only few clinical studies (Tab. 1) in the literature regarding the use of MSCs for tendon therapy. Ellera-Gomes et al. investigated application of autologous MSCs from iliac crest aspiration on rotator cuff repair. In their cohort report, they demonstrated clinical improvement and integrity of all repairs treated with MSCs103. Skin derived tenocyte like cells have shown satisfactory results for treatment of elbow lateral epicondylitis (Level evidence IV)104. Comparing the application of these cells with autologous plasma for the treatment of patellar tendinopathy, significant clinical improvement was reported (Level of evidence I), normal histology was reported in a case of a late rupture from the experimental group105.

Table 1.

Use of MSCs for tendon pathologies in randomized controlled trials.

| Author | Study Design | Diagnosis | Source of MSCs | Comparison Group | n | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clarke, et al. (2011) | Level I: Randomized double blind controlled trial | Refractory patellar tendinopathy | Skin derived tenocyte like cells | Autologous Plasma | 60 | Statistical difference in the cell group in clinical outcomes (VISA), No statistical difference in appearance between groups (USG). |

| Connell, et al. (2009) | Level IV: Prospective clinical pilot study | Refractory lateral epicondylitis | Skin derived tenocyte like cells | - | 12 | Improvement in pain and function in clinical outcomes (PRTEE). Tendency towards tendon normality (USG). |

| Ellera-Gomes, et al. (2011) | Level IV: Cohort | Rotator Cuff tear | BMMSCs | - | 14 | Improvement in pain and function in clinical outcomes (UCLA). Integrity of repaired tendon in all cases (MRI). |

BMMSCs, Bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells; MRI, Magnetic resonance images; PRTEE, Patient Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation; UCLA, the University of California at Los Angeles score;USG, ultrasonography ; VISA, Victoria Institute of Sport Assessment score.

Although results from in vitro and animal studies revealed great potential of MSCs to improve tendon regeneration, the final relevance of MSCs for clinical applications in tendon therapies is not yet assessable. Here, randomized, controlled trials have to follow.

Discussion

In the last decades plenty research has focused upon improving tendon regeneration after surgery. Despite surgical development to achieve this goal, impaired healing within the tendon continues to be a main problem in the orthopedic practice3.

In this review both PRP and MSCs have shown to work as a carrier of growth factors into the repair site. PRP has proven to deliver growth factors in vitro4,5,8,9,12,13,18,106. These may increase angiogenesis13,14,18 and may act as an anti-inflammatory agent25,26. Also MSCs have proven to deliver high amounts of growth factors due to their exceptional paracrine activity83,84,107. In addition, when different factors are added they inhere the potential to differentiate into tenocytes77–82.

Animal studies revealed that both, PRP and MSCs, have the potential to improve histological and biomechanical properties of regenerated tendons29–31,71,72,75,91–93,95,97,98. Application of MSCs even resulted in regeneration of the enthesis in a rat model7,91,92.

Although the benefits from PRP seemed to be encouraging in preclinical studies28–31, PRP failed to prove significant, reproducible impact on regeneration in patients42–46,48–52. This is the reason why further studies are needed to improve the capabilities of the PRP use54. Use of MSCs in animal models are promising7,91–93,95,97. However, mesenchymal stem cell based therapies for tendon healing have not yet reached the patient, except of some pilot trials102–105. Here, randomized, controlled trials will be needed in future to investigate possible relevance and efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell therapies on tendon pathologies.

Conclusion

Current evidence shows that both, PRP and MSCs work as efficient growth factor carriers, however clinical results of PRP do not correlate with the promising preclinical results and further studies may clear the promising benefit of its use. Current evidence supports the tendon healing potential due to great MSCs characteristics, clinical results are promising, tissue engineering might prove their great features.

References

- 1.Padulo J, Oliva F, Frizziero A, Maffulli N. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research. MLTJ. 2013;4:250–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu CF, Aschbacher-Smith L, Barthelery NJ, Dyment N, Butler D, Wylie C. What we should know before using tissue engineering techniques to repair injured tendons: a developmental biology perspective. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2011;17(3):165–176. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2010.0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang JH, Guo Q, Li B. Tendon biomechanics and mechanobiology—a minireview of basic concepts and recent advancements. J Hand Ther. 2012;25(2):133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2011.07.004. quiz 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wurgler-Hauri CC, Dourte LM, Baradet TC, Williams GR, Soslowsky LJ. Temporal expression of 8 growth factors in tendon-to-bone healing in a rat supraspinatus model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5 Suppl):S198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyras DN, Kazakos K, Agrogiannis G, et al. Experimental study of tendon healing early phase: is IGF-1 expression influenced by platelet rich plasma gel? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96(4):381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchmann S, Sandmann GH, Walz L, et al. Refixation of the supraspinatus tendon in a rat model—influence of continuous growth factor application on tendon structure. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(2):300–305. doi: 10.1002/jor.22211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nourissat G, Diop A, Maurel N, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy regenerates the native bone-tendon junction after surgical repair in a degenerative rat model. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jo CH, Kim JE, Yoon KS, Shin S. Platelet-rich plasma stimulates cell proliferation and enhances matrix gene expression and synthesis in tenocytes from human rotator cuff tendons with degenerative tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1035–1045. doi: 10.1177/0363546512437525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, et al. The positive effects of different platelet-rich plasma methods on human muscle, bone, and tendon cells. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(8):1742–1749. doi: 10.1177/0363546512452713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2004;62(4):489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molloy T, Wang Y, Murrell G. The roles of growth factors in tendon and ligament healing. Sports Med. 2003;33(5):381–394. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anitua E, Andia I, Ardanza B, Nurden P, Nurden AT. Autologous platelets as a source of proteins for healing and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91(1):4–15. doi: 10.1160/TH03-07-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyras DN, Kazakos K, Verettas D, et al. The effect of platelet-rich plasma gel in the early phase of patellar tendon healing. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(11):1577–1582. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0935-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anitua E, Andia I, Sanchez M, Azofra J. Autologous preparations rich in growth factors promote proliferation and induce VEGF and HGF production by human tendon cells in culture. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2005;23 doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Middleton KK, Barro V, Muller B, Terada S, Fu FH. Evaluation of the effects of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy involved in the healing of sports-related soft tissue injuries. Iowa Orthop J. 2012;32:150–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaux JF, Janssen L, Drion P, et al. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-111 (VEGF-111) and tendon healing: preliminary results in a rat model of tendon injury. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(1):24–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaux JF, Janssen L, Drion P, et al. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-111 (VEGF-111) and tendon healing: preliminary results in a rat model of tendon injury. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(1):24–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Mos M, van der Windt AE, Jahr H, et al. Can platelet-rich plasma enhance tendon repair? A cell culture study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1171–1178. doi: 10.1177/0363546508314430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beitzel K, McCarthy MB, Cote MP, et al. The effect of ketorolac tromethamine, methylprednisolone, and platelet-rich plasma on human chondrocyte and tenocyte viability. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(7):1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muto T, Kokubu T, Mifune Y, et al. Platelet-rich plasma protects rotator cuff-derived cells from the deleterious effects of triamcinolone acetonide. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(6):976–982. doi: 10.1002/jor.22301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bausset O, Magalon J, Giraudo L, et al. Impact of local anaesthetics and needle calibres used for painless PRP injections on platelet functionality. Muscles LigamentsTendons J. 2014;4(1):18–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molnar C, Garcia-Trevijano ER, Ludwiczek O, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of hepatocyte growth factor: induction of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2004;15(4):303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Middleton KK, Fu FH, Im HJ, Wang JH. HGF mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of PRP on injured tendons. PLoSOne. 2013;8(6):e67303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homsi E, Janino P, Amano M, Saraiva Camara NO. Endogenous hepatocyte growth factor attenuates inflammatory response in glycerol-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Nephrol. 2009;29(4):283–91. doi: 10.1159/000159275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen DB, Kawamura S, Ehteshami JR, Rodeo SA. In-domethacin and celecoxib impair rotator cuff tendon-to-bone healing. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):362–369. doi: 10.1177/0363546505280428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferry ST, Afshari HM, Lee JA, Dahners LE, Weinhold PS. Effect of prostaglandin E2 injection on the structural properties of the rat patellar tendon. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2012;4(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1758-2555-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, Wang JH. PRP treatment effects on degenerative tendinopathy - an in vitro model study. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(1):10–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane JG, Healey RM, Chase DC, Amiel D. Use of platelet-rich plasma to enhance tendon function and cellularity. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2013;42(5):209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HJ, Nam HW, Hur CY, et al. The effect of platelet rich plasma from bone marrow aspirate with added bone morpho-genetic protein-2 on the Achilles tendon-bone junction in rabbits. Clin Orthop Surg. 2011;3(4):325–331. doi: 10.4055/cios.2011.3.4.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosch G, van Schie HT, de Groot MW, et al. Effects of platelet-rich plasma on the quality of repair of mechanically induced core lesions in equine superficial digital flexor tendons: A placebo-controlled experimental study. J Orthop Res. 2010;28(2):211–217. doi: 10.1002/jor.20980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck J, Evans D, Tonino PM, Yong S, Callaci JJ. The biomechanical and histologic effects of platelet-rich plasma on rat rotator cuff repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9):2037–2044. doi: 10.1177/0363546512453300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kajikawa Y, Morihara T, Sakamoto H, et al. Platelet-rich plasma enhances the initial mobilization of circulation-derived cells for tendon healing. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215(3):837–845. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrett S, Erredge S. Growth factors for chronic plantar fascitis. Podiatry Today. 2004;17:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez M, Anitua E, Azofra J, Andia I, Padilla S, Mujika I. Comparison of surgically repaired Achilles tendon tears using platelet-rich fibrin matrices. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):245–251. doi: 10.1177/0363546506294078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kon E, Filardo G, Delcogliano M, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: new clinical application: a pilot study for treatment of jumper’s knee. Injury. 2009;40(6):598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filardo G, Kon E, Della Villa S, Vincentelli F, Fornasari PM, Marcacci M. Use of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of refractory jumper’s knee. Int Orthop. 2010;34(6):909–915. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0845-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaweda K, Tarczynska M, Krzyzanowski W. Treatment of Achilles tendinopathy with platelet-rich plasma. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31(8):577–583. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barber FA, Hrnack SA, Snyder SJ, Hapa O. Rotator cuff repair healing influenced by platelet-rich plasma construct augmentation. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(8):1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owens RF, Jr, Ginnetti J, Conti SF, Latona C. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging outcomes following platelet rich plasma injection for chronic midsubstance Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(11):1032–1039. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2011.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monto RR. Platelet rich plasma treatment for chronic Achilles tendinosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(5):379–385. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Vos RJ, Weir A, van Schie HT, et al. Platelet-rich plasma injection for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2010;303(2):144–149. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Castricini R, Longo UG, De Benedetto M, et al. Platelet-rich plasma augmentation for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):258–265. doi: 10.1177/0363546510390780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Creaney L, Wallace A, Curtis M, Connell D. Growth factor-based therapies provide additional benefit beyond physical therapy in resistant elbow tendinopathy: a prospective, single-blind, randomised trial of autologous blood injections versus platelet-rich plasma injections. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(12):966–971. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.082503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jo CH, Kim JE, Yoon KS, et al. Does platelet-rich plasma accelerate recovery after rotator cuff repair? A prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2082–2090. doi: 10.1177/0363546511413454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Ragone V, Aliprandi A, Cabitza P. Platelet rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective RCT study, 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schepull T, Kvist J, Norrman H, Trinks M, Berlin G, Aspenberg P. Autologous platelets have no effect on the healing of human achilles tendon ruptures: a randomized single-blind study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(1):38–47. doi: 10.1177/0363546510383515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thanasas C, Papadimitriou G, Charalambidis C, Paraskevopoulos I, Papanikolaou A. Platelet-rich plasma versus autologous whole blood for the treatment of chronic lateral elbow epicondylitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2130–2134. doi: 10.1177/0363546511417113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Jonge S, de Vos RJ, Weir A, et al. One-year follow-up of platelet-rich plasma treatment in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(8):1623–1629. doi: 10.1177/0363546511404877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Omar AS, Ibrahim ME, Ahmed AS, Said M. Local injection of autologous platelet rich plasma and corticosteroid in treatment of lateral epicondylitis and plantar fasciitis: Randomized clinical trial. The Egyptian Rheumatologist. 2012;34(2):43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kesikburun S, Tan AK, Yilmaz B, Yasar E, Yazicioglu K. Platelet-rich plasma injections in the treatment of chronic rotator cuff tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11):2609–2616. doi: 10.1177/0363546513496542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krogh TP, Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Christensen R, Jensen P, Ellingsen T. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):625–635. doi: 10.1177/0363546512472975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mishra AK, Skrepnik NV, Edwards SG, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma for chronic tennis elbow: a double-blind, prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial of 230 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):463–471. doi: 10.1177/0363546513494359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peerbooms JC, Sluimer J, Bruijn DJ, Gosens T. Positive effect of an autologous platelet concentrate in lateral epicondylitis in a double-blind randomized controlled trial: platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection with a 1-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(2):255–262. doi: 10.1177/0363546509355445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andia I, Latorre PM, Gomez MC, Burgos-Alonso N, Abate M, Maffulli N. Platelet-rich plasma in the conservative treatment of painful tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Br Med Bull. 2014 Jun;110(1):99–115. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldu007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zimmermann R, Jakubietz R, Jakubietz M, et al. Different preparation methods to obtain platelet components as a source of growth factors for local application. Transfusion. 2001;41(10):1217–1224. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41101217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harrison S, Vavken P, Kevy S, Jacobson M, Zurakowski D, Murray MM. Platelet activation by collagen provides sustained release of anabolic cytokines. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(4):729–734. doi: 10.1177/0363546511401576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DohanEhrenfest DM, Andia I, Zumstein MA, Zhang CQ, Pinto NR, Bielecki T. Classification of platelet concentrates (Platelet-Rich Plasma-PRP, Platelet-Rich Fibrin-PRF) for topical and infiltrative use in orthopedic and sports medicine: current consensus, clinical implications and perspectives. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(1):3–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castillo TN, Pouliot MA, Kim HJ, Dragoo JL. Comparison of growth factor and platelet concentration from commercial platelet-rich plasma separation systems. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):266–271. doi: 10.1177/0363546510387517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beitzel K, McCarthy MB, Russell RP, Apostolakos J, Cote MP, Mazzocca AD. Learning about PRP using cell-based models. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(1):38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Foster TE, Puskas BL, Mandelbaum BR, Gerhardt MB, Rodeo SA. Platelet-rich plasma: from basic science to clinical applications. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2259–2272. doi: 10.1177/0363546509349921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ehnert S, Glanemann M, Schmitt A, et al. The possible use of stem cells in regenerative medicine: dream or reality? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394(6):985–997. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmitt A, van Griensven M, Imhoff AB, Buchmann S. Application of stem cells in orthopedics. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:394962. doi: 10.1155/2012/394962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saha K, Jaenisch R. Technical challenges in using human induced pluripotent stem cells to model disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(6):584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kassem M, Kristiansen M, Abdallah BM. Mesenchymal stem cells: cell biology and potential use in therapy. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;95(5):209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2004.pto950502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chaudhury S. Mesenchymal stem cell applications to tendon healing. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;2(3):222–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Manning CN, Schwartz AG, Liu W, et al. Controlled delivery of mesenchymal stem cells and growth factors using a nanofiber scaffold for tendon repair. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(6):6905–6914. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ju YJ, Muneta T, Yoshimura H, Koga H, Sekiya I. Synovial mesenchymal stem cells accelerate early remodeling of tendon-bone healing. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;332(3):469–478. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0610-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Omae H, Mochizuki Y, Yokoya S, Adachi N, Ochi M. Augmentation of tendon attachment to porous ceramics by bone marrow stromal cells in a rabbit model. Int Orthop. 2007;31(3):353–358. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0194-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, Cote MP, Arciero RA, Drissi H. Rapid isolation of human stem cells (connective tissue progenitor cells) from the proximal humerus during arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1438–1447. doi: 10.1177/0363546509360924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li YG, Wei JN, Lu J, Wu XT, Teng GJ. Labeling and tracing of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for tendon-to-bone tunnel healing. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(12):2153–2158. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yao J, Woon CY, Behn A, et al. The effect of suture coated with mesenchymal stem cells and bioactive substrate on tendon repair strength in a rat model. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(8):1639–1645. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yokoya S, Mochizuki Y, Natsu K, Omae H, Nagata Y, Ochi M. Rotator cuff regeneration using a bioabsorbable material with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a rabbit model. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(6):1259–1268. doi: 10.1177/0363546512442343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Utsunomiya H, Uchida S, Sekiya I, Sakai A, Moridera K, Nakamura T. Isolation and characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from shoulder tissues involved in rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):657–668. doi: 10.1177/0363546512473269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ouyang HW, Goh JC, Lee EH. Viability of allogeneic bone marrow stromal cells following local delivery into patella tendon in rabbit model. Cell Transplant. 2004;13(6):649–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guest DJ, Smith MR, Allen WR. Monitoring the fate of autologous and allogeneic mesenchymal progenitor cells injected into the superficial digital flexor tendon of horses: preliminary study. Equine Vet J. 2008;40(2):178–181. doi: 10.2746/042516408X276942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Violini S, Ramelli P, Pisani LF, Gorni C, Mariani P. Horse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells express embryo stem cell markers and show the ability for tenogenic differentiation by in vitro exposure to BMP-12. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee JY, Zhou Z, Taub PJ, et al. BMP-12 treatment of adult mesenchymal stem cells in vitro augments tendon-like tissue formation and defect repair in vivo. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec D, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells obtained during arthroscopic rotator cuff repair surgery show potential for tendon cell differentiation after treatment with insulin. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(11):1459–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alberton P, Popov C, Pragert M, et al. Conversion of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells into tendon progenitor cells by ectopic expression of scleraxis. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(6):846–858. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kishore V, Bullock W, Sun X, Van Dyke WS, Akkus O. Tenogenic differentiation of human MSCs induced by the topography of electrochemically aligned collagen threads. Biomaterials. 2012;33(7):2137–2144. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tan SL, Ahmad RE, Ahmad TS, et al. Effect of growth differentiation factor 5 on the proliferation and tenogenic differentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Cells Tissues Organs. 2012;196(4):325–338. doi: 10.1159/000335693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gangji V, Hauzeur JP, Matos C, De Maertelaer V, Toungouz M, Lambermont M. Treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head with implantation of autologous bone-marrow cells. A pilot study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-a(6):1153–1160. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hernigou P, Poignard A, Zilber S, Rouard H. Cell therapy of hip osteonecrosis with autologous bone marrow grafting. Indian J Orthop. 2009;43(1):40–45. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.45322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Salama R, Weissman SL. The clinical use of combined xenografts of bone and autologous red marrow. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1978;60(1):111–115. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.60B1.342531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yu XY, Geng YJ, Li XH, et al. The effects of mesenchymal stem cells on c-kit up-regulation and cell-cycle re-entry of neonatal cardiomyocytes are mediated by activation of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;332(1–2):25–32. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen TS, Lai RC, Lee MM, Choo AB, Lee CN, Lim SK. Mesenchymal stem cell secretes microparticles enriched in pre-microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(1):215–224. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ryan JM, Barry FP, Murphy JM, Mahon BP. Mesenchymal stem cells avoid allogeneic rejection. J Inflamm (Lond) 2005;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bernardo ME, Locatelli F, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Novel Treatment Modality for Tissue Repair. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1176:101–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lui PP, Wong OT. Tendon stem cells: experimental and clinical perspectives in tendon and tendon-bone junction repair. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;2(3):163–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lim JK, Hui J, Li L, Thambyah A, Goh J, Lee EH. Enhancement of tendon graft osteointegration using mesenchymal stem cells in a rabbit model of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(9):899–910. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Soon MY, Hassan A, Hui JH, Goh JC, Lee EH. An analysis of soft tissue allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in a rabbit model: a short-term study of the use of mesenchymal stem cells to enhance tendon osteointegration. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(6):962–971. doi: 10.1177/0363546507300057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schnabel LV, Lynch ME, van der Meulen MC, Yeager AE, Kornatowski MA, Nixon AJ. Mesenchymal stem cells and insulin-like growth factor-I gene-enhanced mesenchymal stem cells improve structural aspects of healing in equine flexor digitorum superficialis tendons. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(10):1392–1398. doi: 10.1002/jor.20887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gulotta LV, Kovacevic D, Montgomery S, Ehteshami JR, Packer JD, Rodeo SA. Stem cells genetically modified with the developmental gene MT1-MMP improve regeneration of the supraspinatus tendon-to-bone insertion site. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1429–1437. doi: 10.1177/0363546510361235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Okamoto N, Kushida T, Oe K, Umeda M, Ikehara S, Iida H. Treating Achilles tendon rupture in rats with bone-marrow-cell transplantation therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(17):2776–2784. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gulotta LV, Kovacevic D, Packer JD, Deng XH, Rodeo SA. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells transduced with scleraxis improve rotator cuff healing in a rat model. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1282–1289. doi: 10.1177/0363546510395485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Huang TF, Yew TL, Chiang ER, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from a hypoxic culture improve and engraft Achilles tendon repair. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(5):1117–1125. doi: 10.1177/0363546513480786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Harris MT, Butler DL, Boivin GP, Florer JB, Schantz EJ, Wenstrup RJ. Mesenchymal stem cells used for rabbit tendon repair can form ectopic bone and express alkaline phosphatase activity in constructs. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(5):998–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Awad HA, Boivin GP, Dressler MR, Smith FN, Young RG, Butler DL. Repair of patellar tendon injuries using a cell-collagen composite. J Orthop Res. 2003;21(3):420–431. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rui YF, Lui PP, Ni M, Chan LS, Lee YW, Chan KM. Mechanical loading increased BMP-2 expression which promoted osteogenic differentiation of tendon-derived stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(3):390–396. doi: 10.1002/jor.21218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang J, Wang JH. Production of PGE(2) increases in tendons subjected to repetitive mechanical loading and induces differentiation of tendon stem cells into non-tenocytes. J Orthop Res. 2010;28(2):198–203. doi: 10.1002/jor.20962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Centeno CJ, Schultz JR, Cheever M, et al. Safety and complications reporting update on the re-implantation of culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells using autologous platelet lysate technique. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2011;6(4):368–378. doi: 10.2174/157488811797904371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ellera Gomes JL, da Silva RC, Silla LM, Abreu MR, Pellanda R. Conventional rotator cuff repair complemented by the aid of mononuclear autologous stem cells. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(2):373–377. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1607-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Connell D, Datir A, Alyas F, Curtis M. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis using skin-derived tenocyte-like cells. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(4):293–298. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.056457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Clarke AW, Alyas F, Morris T, Robertson CJ, Bell J, Connell DA. Skin-derived tenocyte-like cells for the treatment of patellar tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(3):614–623. doi: 10.1177/0363546510387095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang JH. Can PRP effectively treat injured tendons? Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(1):35–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Via AG, Frizziero A, Oliva F. Biological properties of mesenchymal Stem Cells from different sources. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;2(3):154–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]