Abstract

Prebiotic oligosaccharides are increasingly demanded within the Food Science domain because of the interesting healthy properties that these compounds may induce to the organism, thanks to their beneficial intestinal microbiota growth promotion ability. In this regard, the development of new efficient, convenient and affordable methods to obtain this class of compounds might expand even further their use as functional ingredients. This review presents an overview on the most recent interesting approaches to synthesize lactose-derived oligosaccharides with potential prebiotic activity paying special focus on the microbial glycoside hydrolases that can be effectively employed to obtain these prebiotic compounds. The most notable advantages of using lactose-derived carbohydrates such as lactosucrose, galactooligosaccharides from lactulose, lactulosucrose and 2-α-glucosyl-lactose are also described and commented.

Introduction

Since Gibson and Roberfroid introduced the concept of prebiotics as non-digestible oligosaccharides that reach the colon without being hydrolyzed and are selectively metabolized by health-positive bacteria such as bifidobacteria and lactobacilli (Gibson and Roberfroid, 1995), there is a growing consumer interest in functional foods containing this class of compounds. Given that they contribute to enhance the growth of the beneficial intestinal microbiota and prevent the spread of pathogenic microorganisms, a number of functional foods based on the presence of prebiotic carbohydrates have been introduced into the market.

The prebiotic properties of oligosaccharides are determined by its monosaccharide composition and their glycosidic linkages (Sanz et al., 2005). Thus, the search for new prebiotic carbohydrates with improved properties has attracted great interest in academic and industrial food research. Today, there are a wide range of emerging potential prebiotics demanding robust data from human studies to be included in the world prebiotic market along with lactulose and galactooligosaccharides (GOS), both obtained from lactose, being two of the most widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries.

Whey permeate, a waste product of the cheese industry obtained by ultrafiltration of cheese whey, contains most of the lactose originally present in milk and has a high biological oxygen demand (BOD), thereby depleting the dissolved oxygen content of the receiving water. Given the large quantity of cheese annually produced worldwide (OECD-FAO, 2013), the use of whey permeate as raw material for the production of valuable lactose derivatives is a challenge for research and industry.

In general, enzymatic processes have a great potential in the food carbohydrate field, as they normally exhibit high yields, substrate specificity, regio- and stereospecificity (Buchholz and Seibel, 2008). Oligosaccharides are normally formed from mono- and/or disaccharides that participate in glycosyl transfer reactions catalyzed by specific enzymes. For their application in foodstuffs, both the initial substrates and enzymes must have a generally recognized as safe status, reasonable cost and be easily available. Lactose and sucrose buffered solutions, as well as dairy and sugar by-products containing these disaccharides are suitable starting materials for the synthesis of functional oligosaccharides.

Enzymes devoted to the synthesis of oligosaccharides can be obtained from a wide variety of sources such as microorganisms, plants and animals. However, microbial enzymes are normally preferred for industrial production as they exhibit a number of important advantages such as (i) easier handling, (ii) higher multiplication rate, (iii) higher production yields (greater catalytic activity), (iv) genes encoding for microbial enzymes are efficiently translated and expressed as active proteins in bacteria such as Escherichia coli, (v) economic feasibility (i.e. fermentation for microbial expression systems are carried out on inexpensive media), (vi) enhanced versatility on acceptor substrates, (vii) better stability and (viii) regular supply due to absence of seasonal fluctuations, among others (Panesar et al., 2006; Filice and Marciello, 2013; Gurung et al., 2013). Consequently, an important number of microbial enzymes produced by fungi, bacteria or yeasts have been employed for the efficient synthesis of a wide range of dietary bioactive oligosaccharides as it is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Microbial glycoside hydrolase enzymes most frequently used for the synthesis of food bioactive oligosaccharides

| Synthesized Oligosaccharide | General structurea [main linkages] | Involved enzymes (EC number) | Enzyme Source (microorganism) | GH familyb | Sugar substrate (reaction type) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fructo-oligosaccharides | (Fru)n-Glc [β(2→1), β(2→6)] | β-Fructofuranosidase (EC 3.2.1.26) Inulosucrase (EC 2.4.1.9) Levansucrase (EC 2.4.1.10) | Fungi (Aspergillus niger; A. japonicus; A. oryzae; Aureobasidium pullulans; Penicillium citrinum) Bacteria (Bacillus macerans; Zymomonas mobilis; Lactobacillus reuteri; Arthrobacter sp.) | 32, 68, 100 | Sucrose (transfructosylation) | Sangeetha et al., 2005 |

| Galacto-oligosaccharides | (Gal)n-Glc (Gal)n-Gal [β(1→3), β(1→4), β(1→6)] | β-Galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.23) | Fungi (A. oryzae; A. niger; A. aculeatus) Bacteria (Bacillus sp.; Streptococcus thermophilus; Lactobacillus acidophilus; L. reuteri; Bifidobacterium sp.) Yeast (Kluyveromyces lactis; K. marxianus; Saccharomyces fragilis; Cryptococcus laurentii) | 1, 2, 3, 35, 42, 50 | Lactose (transgalactosylation) | Panesar et al., 2006 |

| Torres et al., 2010 | ||||||

| Galacto-oligosaccharides derived from lactulose | (Gal)n-Fru (Gal)n-Gal (Gal)n-Fru-Gal [β(1→1), β(1→4), β(1→6)] | β-Galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.23) | Fungi (A. oryzae; A. aculeatus) Yeast (K. lactis) | 1, 2, 3, 35, 42, 50 | Lactulose (transgalactosylation) | Cardelle-Cobas et al., 2008 |

| Martínez-Villaluenga et al., 2008b | ||||||

| Lactosucrose | β-Gal-(1→4)-α-Glc-(1→2)-β-Fru | β-Fructofuranosidase (EC 3.2.1.26) Levansucrase (EC 2.4.1.10) or β-Galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.23) | Bacteria (Arthrobacter sp. K-1; Z. mobilis; Bacillus subtilis; B. natto; B. circulans) | 32, 68, 100 or 1, 2, 3, 35, 42, 50 | Lactose and sucrose (transfructosylation of lactose or transgalactosylation of sucrose) | Takahama et al., 1991 |

| Pilgrim et al., 2001 | ||||||

| Park et al., 2005 | ||||||

| Han et al., 2009 | ||||||

| Li et al., 2009 | ||||||

| Lactulosucrose | β-Gal-(1→4)-β-Fru-(2→1)-α-Glc | Dextransucrase (EC 2.4.1.5) | Bacteria (Leuconostoc mesenteroides) | 70 | Lactulose and sucrose (transglucosylation) | Díez-Municio et al., 2012a |

| 2-α-glucosyl-lactose | β-Gal-(1→4)-α-Glc-(2→1)-α-Glc | Dextransucrase (EC 2.4.1.5) | Bacteria (L. mesenteroides) | 70 | Lactose and sucrose (transglucosylation) | Díez-Municio et al., 2012b |

| Isomalto-oligosaccharides | (Glc)n [α(1→6)] | A) α-Amylase (EC 3.2.1.1) and Pullulanase (EC 3.2.1.41) B) α-Glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.20) | Fungi (Aspergillus sp.; Aureobasidium pullulans) Bacteria (Bacillus subtilis; B. licheniformis; B. stearothermophilus) | A) 13, 14, 57, 119 B) 4, 13, 31, 63, 97, 122 | Starch [hydrolysis (A) and transglucosylation (B)] | Casci and Rastall, 2006 |

| Goffin et al., 2011 | ||||||

| Gluco-oligosaccharides | (Glc)n [α(1→2), α(1→3), α(1→4), α(1→6)]. | Dextransucrase (EC 2.4.1.5) | Bacteria (L. mesenteroides; L. citreum) | 70 | Maltose and sucrose (transglucosylation) | Remaud et al., 1992 |

| Chung and Day, 2002 | ||||||

| Kim et al., 2014 | ||||||

| Gentio-oligosaccharides | (Glc)n [β(1→6)] | Glucan endo-1,6-β-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.75) or β-Glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.21) | Fungi (Penicillium multicolor; A. oryzae) | 5, 30 or 1, 3, 5, 9, 30, 116 | Pustulan (hydrolysis) or Gentibiose (transglucosylation) | Fujimoto et al., 2009 |

| Qin et al., 2011 | ||||||

| Pectic-oligosaccharides | (GalA)n [α(1→4)] (GalA-Rha)n [α(1→2), α(1→4)] * GalA residues can be partially esterified and Rha units ramified. | Polygalacturonase (EC 3.2.1.15) Rhamnogalacturonan galacturonohydrolase (EC 3.2.1.173) Rhamnogalacturonan rhamnohydrolase (EC 3.2.1.174) | Fungi (Fusarium moniliforme; Aspergillus pulverulentus; A. aculeatus; Kluyveromyces fragilis) Bacteria (B. licheniformis) | 28 | Pectin (hydrolysis) | Spiro et al., 1993 |

| Olano-Martin et al., 2001 | ||||||

| Coenen et al., 2008 | ||||||

| Holck et al., 2011 | ||||||

| Xylo-oligosaccharides | (Xyl)n [β(1→4)] | Endo-1,4-β-xylanase (EC 3.2.1.8) β-Xylosidase (EC 3.2.1.37) | Fungi (Trichoderma sp.; A. oryzae) | 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 26, 30, 43, 44, 51, 62 | Xylan (hydrolysis) | Casci and Rastall, 2006 |

| Maltosyl-fructosides | (Fru)n-Malt [β(2→1), β(2→6)] | Levansucrase (EC 2.4.1.10) Inulosucrase (EC 2.4.1.9) | Bacteria (B. subtilis; Lactobacillus gasseri) | 32, 68 | Maltose and sucrose (transfructosylation) | Canedo et al., (1999) |

| Díez-Municio et al., (2013b) |

Glc, glucose; Fru, fructose; Gal, galactose; GalA, galacturonic acid; Rha, rhamnose; Xyl, xylose; Malt, maltose.

According to CAZy database.

This review will firstly deal with the classification and structural features of the main microbial enzymes involved in the synthesis of food bioactive oligosaccharides, as well as the insights into the catalytic mechanism. Then, it will focus on a series of recently synthesized lactose-derived oligosaccharides, such as GOS derived from lactulose, lactulosucrose or 2-α-glucosyl-lactose, whose characterized chemical structures point out their utility as emerging bioactive food ingredients.

Classification of microbial enzymes involved in the synthesis of food bioactive oligosaccharides

International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (IUBMB) enzyme nomenclature

There are different systems used to classify enzymes. Concretely, enzymes involved in the synthesis of food bioactive oligosaccharides have been traditionally classified as glycosidases and glycosyltransferases (GTs) according to the recommendations of the IUBMB, which is based mostly on substrate specificity and is expressed in the Enzyme Commission (EC) number for a given enzyme (http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/enzyme/). Consequently, glycosidases, i.e. enzymes that hydrolyze O- and S-glycosyl compounds, are given the code 3.2.1.x, where × represents the substrate specificity and, occasionally, also the molecular mechanism or type of glycosidic linkage (Henrissat and Davies, 1997). GTs (EC 2.4) are capable of transferring glycosyl groups, from one compound (known as donor), to water or another compound (acceptor) catalyzing, thus, oligosaccharide synthesis (Monsan and Paul, 1995). This type of enzymes are further subdivided, according to the nature of the sugar residue being transferred, into hexosyltransferases (EC 2.4.1), pentosyltransferases (EC 2.4.2), and those transferring other glycosyl groups (EC 2.4.99) (Plou et al., 2002). This classification system has several limitations, such as EC numbers cannot accommodate enzymes that act on several distinct substrates or do not reflect the intrinsic structural and mechanistic features of the enzymes (Coutinho et al., 2003).

Consequently, GTs can be also classified according to the nature of the donor molecule into three main mechanistic groups: (i) Leloir-type GTs, which require sugar nucleotides derivatives [monosaccharide (di)phosphonucleotides], (ii) non-Leloir GTs that utilize non-nucleotide donors, which may be sugar-1-phosphates, sugar-1-pyrophosphates, polyprenol phosphates or polyprenol pyrophosphates and (iii) transglycosidases, which employ non-activated sugars such as sucrose, lactose or starch (Plou et al., 2007). Within transglycosidases, glycansucrases are a class of microbial enzymes that polymerize either the fructosyl (i.e. fructansucrases) or the glucosyl (i.e. glucansucrases) moiety of sucrose to give β-D-fructan- or α-D-glucan-type polysaccharides. Interestingly, this type of enzymes has also the ability to transfer fructosyl or glucosyl units to suitable acceptor molecules to yield dietary oligosaccharides, and, consequently, are considered as attractive synthetic tools (André et al., 2010; Côté, 2011). Dextransucrases (EC 2.4.1.5) or alternansucrases (2.4.1.140) and inulosucrases (EC 2.4.1.9) or levansucrases (EC 2.4.1.10) are among the most-used microbial glucansucrases and fructansucrases, respectively, in oligosaccharide synthesis from sucrose (van Hijum et al., 2006).

Carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy)

In 1991, Henrissat (1991) introduced a classification of glycosidases [glycoside hydrolases (GHs)] based upon amino acid sequence similarities. This classification was settled on the principle that sequence and structure are related and, hence, useful structural and mechanistic information could be inferred from this classification system (Henrissat and Davies, 1997). That initial classification has evolved to the CAZy database (http://www.cazy.org), which describes the families of structurally related catalytic and carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs; or functional domains) of enzymes that degrade, modify or create glycosidic bonds (Lombard et al., 2014). Currently, CAZy covers more than 300 protein families divided in Glycoside hydrolases (GHs, hydrolysis and/or rearrangement of glycosidic bonds), GTs (formation of glycosidic bonds), Polysaccharide lyases (non-hydrolytic cleavage of glycosidic bonds), Carbohydrate esterases (hydrolysis of carbohydrate esters), auxiliary activities [redox enzymes that act in conjunction with carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes)], as well as CBMs (adhesion to carbohydrates).

It is noteworthy to remark that transglycosidases and glycosidases are structurally, mechanistically and evolutionarily related and, therefore, they are included in the GH family in the CAZy classification (Coutinho et al., 2003). In consequence, according to this classification, GHs comprise, up to now, 133 families converging upon similar active sites for the cleavage of glycosidic linkages. From now on, we will focus on this type of enzymes given its relevance in the synthesis of food bioactive oligosaccharides (Table 1).

Structural and catalytic insights into microbial GHs used for the synthesis of food bioactive oligosaccharides

Three-dimensional structure determination of GHs

Three-dimensional structural studies are essential to reveal the identity of important amino acid residues involved in catalysis and to elucidate the mechanism in the enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharides. It is largely known that the substrate specificity and the mode of action of GHs are driven by details of their three-dimensional structures rather than by their global fold (Davies and Henrissat, 1995). In this sense, structural analyses and site-directed mutagenesis studies carried out in GHs have revealed that linkage specificity is controlled by the topology of only a few key amino acids located at the enzyme active site (Irague et al., 2013).

Regarding microbial β-galactosidases, 13 crystal structures have been elucidated to date and included in the Protein Data Bank (PDB; http://www.rcsb.org). Table 2 shows the PDB accession code (PDB ID) and the GH family of these enzymes. The β-galactosidases from Kluyveromyces lactis and Aspergillus oryzae are commercially available and they are the most frequently used in food industry for the treatment of milk and whey (Pereira-Rodríguez et al., 2012; Maksimainen et al., 2013). Additionally, as it will be explained below in more detail, these enzymes are also employed for the efficient synthesis of oligosaccharides by transgalactosylation of lactose and lactulose (Table 1).

Table 2.

Microbial β-galactosidases and glycansucrases whose three-dimensional structures have been elucidated and included in the Protein Data Bank

| Microbial enzyme source | PDB ID | GH family | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Galactosidases | |||

| Sulfolobus solfataricus | 1UWR | 1 | Gloster et al., 2004 |

| Escherichia coli | 1DP0 | 2 | Juers et al., 2000 |

| Arthrobacter sp. C2-2 | 1YQ2 | 2 | Skalova et al., 2005 |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 3FN9 | 2 | Unpublished |

| Kluyveromyces lactis | 3OB8 | 2 | Pereira-Rodríguez et al., 2012 |

| Penicillium sp. | 1TG7 | 35 | Rojas et al., 2004 |

| Trichoderma reesei | 3OG2 | 35 | Maksimainen et al., 2011 |

| Caulobacter crescentus | 3U7V | 35 | Unpublished |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | 3D3A | 35 | Unpublished |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 4E8C | 35 | Cheng et al., 2012 |

| Aspergillus oryzae | 4IUG | 35 | Maksimainen et al., 2013 |

| Thermus sp. A4 | 1KWG | 42 | Hidaka et al., 2002 |

| Bacillus circulans sp. alkalophilus | 3TTS | 42 | Maksimainen et al., 2012 |

| Glycansucrases | |||

| Fructansucrases | |||

| Aspergillus japonicus | 3LIH | 32 | Chuankhayan et al., 2010 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 1PT2 | 68 | Meng and Fütterer, 2003 |

| Bacillus megaterium | 3OM2 | 68 | Strube et al., 2011 |

| Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus | 1W18 | 68 | Martínez-Fleites et al., 2005 |

| Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC 533 | 2YFR | 68 | Pijning et al., 2011 |

| Glucansucrases | |||

| Lactobacillus reuteri 180 | 3KLK | 70 | Vujičić-Žagar et al., 2010 |

| Lactobacillus reuteri 121 | 4AMC | 70 | Pijning et al., 2012 |

| Streptococcus mutans | 3AIE | 70 | Ito et al., 2011 |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-1299 | 3TTQ | 70 | Brison et al., 2012 |

As an example, Fig. 1 shows the stereo view of the K. lactis β-galactosidase in its monomeric form, the surface representation, as well as the zoomed view of the active site pocket entrance. These authors elucidated that the monomer folds into five domains in a pattern conserved with other prokaryote enzymes solved for the GH family 2 (Pereira-Rodríguez et al., 2012). The active site of K. lactis β-galactosidase is build up mostly by residues from domain 3, which spans the residues 333–642, but some residues from domain 1 (Asn88, Val89, Asp187) and from domain 5 (Ala1000, Cys1001) also contribute to the narrow entrance that accesses the binding site. The most interesting fact in terms of oligosaccharide synthesis and specificity is the presence of two long insertions in domains 2 (residues 264–274) and 3 (residues 420–443) that shape the catalytic pocket and are unique as compared with other characterized β-galactosidases. Indeed, the unique insertion at loop 420–443 seems to play essential roles in ligand binding and recognition of the lactose molecules, as well as in selecting different acceptor molecules during transgalactosylation (Pereira-Rodríguez et al., 2012). These structural features may explain the high affinity of this enzyme for lactose and, therefore, the high hydrolytic activity against this substrate and the production of oligosaccharides derived from lactose in high amounts by transgalactosylation (Martínez-Villaluenga et al., 2008a).

Fig. 1.

A. Stereo view of Kluyveromyces lactis β-galactosidase monomer in cartoon representation. Domains are represented in different colours. N-terminal region (cyan), domain 1 (blue), domain 2 (green), domain 3 (yellow), domain 4 (orange), linker (magenta) and domain 5 (red). B. Surface representation of the monomer with coloured domains following the same scheme. C. Zoomed view of the catalytic pocket entrance. Residues from domains 1, 5 and, mostly, 3 are building up the pocket entrance. A galactose bound to the active site is shown in stick representation. Reprinted with permission from Pereira-Rodríguez et al. Copyright (2012) Elsevier.

On the other hand, there is more limited information about the three-dimensional structure of microbial glycansucrase enzymes. To date, only four structures of glucansucrases belonging to the GH family 70 have been obtained, including those from Lactobacillus reuteri 180 (Vujičić-Žagar et al., 2010), L. reuteri 121 (Pijning et al., 2012), Streptococcus mutans (Ito et al., 2011) and Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-1299 (Brison et al., 2012) (see PDB accession codes in Table 2). In all cases, the three-dimensional structures were obtained by crystallization of the recombinant truncated forms of the enzymes, which means that crystal structures of complete glucansucrase enzymes have not yet been reported to date (Leemhuis et al., 2013). These four enzymes present different linkage specificity, i.e. α(1→6), α(1→3), α(1→2), but share a common U-type fold, organized into five domains (A, B, C, IV and V). All the domains except domain C are made up from discontinuous segments of the polypeptide chain (Fig. 2). The domain A comprises a (α/β)8 barrel and harbours the catalytic site. In a similar way to GH13 α-amylases, the most important catalytic residues in glucansucrases are a nucleophile (Asp), a general acid/base (Glu) and a transition-state stabilizer (Asp), which lie at the bottom of a deep pocket in domain A (Leemhuis et al., 2013). Additionally, crystal structures combined with site-directed mutagenesis studies revealed that GH70 glucansucrases possess only one active site and have only one nucleophilic residue (Vujičić-Žagar et al., 2010), in contrast to the two-nucleophile mechanism proposed previously by Robyt and colleagues (2008) for dextransucrase enzymes and the mechanism for dextran synthesis.

Fig. 2.

Overall structure of Lactobacillus reuteri 180 GTF180-ΔN glucansucrase.A. Crystal structure of GTF180-ΔN, the N- and the C-terminal ends of the polypeptide chain are indicated, the Ca2+ ion is shown as a magenta sphere.B. Schematic presentation of the ‘U-shaped’ course of the polypeptide chain. Domains A, B, C, IV and V are coloured in blue, green, magenta, yellow and red, respectively, with dark and light colours for the N- and C-terminal stretches of the peptide chain. Reprinted with permission from Vujičić-Žagar et al. Copyright (2010) The National Academy of Sciences.

Regarding fructansucrases, to date, five three-dimensional structures of truncated forms of different bacterial sources have been reported as shown in Table 2. All these enzymes display a five-bladed β-propeller fold, with an active site interacting with the donor substrate sucrose located in a deep pocket at the central axis surrounded by several semiconserved amino acid residues. The bottom of this pocket is tailored for fructosyl binding (Pijning et al., 2011).

Catalytic mechanism of GHs

In general terms, enzymatic hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond takes place via general acid catalysis that requires two critical residues: a proton donor and a nucleophile/base (Davies and Henrissat, 1995). In the case of GHs used for the synthesis of food bioactive oligosaccharides, the hydrolysis occurs through a mechanism that gives rise to an overall retention of the initial conformation on the anomeric carbon (Koshland, 1953). In retaining enzymes, the nucleophilic catalytic base is in close vicinity of the sugar anomeric carbon (Davies and Henrissat, 1995).

The proposed general catalytic mechanism of β-galactosidase is illustrated in Fig. 3. Briefly, catalysis proceeds via a double-displacement reaction in which a covalent galactosyl-enzyme intermediate is formed and hydrolyzed via oxocarbenium ion-like transition states, while glucose is released (Withers, 2001). The active site contains two carboxylic acid residues, which have been identified specifically as Glu461 (proton-donor residue) and Glu537 (catalytic nucleophile group, forming the covalent galactosyl-enzyme intermediate) in the case of the β-galactosidase from E. coli (Juers et al., 2000). The second mechanistic step involves the attack of the covalent galactosyl-enzyme intermediate by a water molecule (hydrolysis) or a sugar molecule (transglycosylation), concomitantly with or followed by the transfer of a proton from a water/sugar to the proton donor, in a reverse mode of the first step (Brás et al., 2010) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

General scheme for the catalytic mechanism of β-galactosidase and a lactose molecule. Reprinted with permission from Brás et al. Copyright (2010) American Chemical Society.

As it could be expected, the catalytic mechanism of glycansucrases is also based on the double-displacement mechanism with retention of the anomeric configuration of the glucosyl/fructosyl moieties (van Hijum et al., 2006). First, the glycosidic linkage of the substrate is cleaved in the active centre of the enzyme between the amino acid residues located at the subsites −1 and +1 (according to the nomenclature proposed by Davies et al., 1997), resulting in a covalent glucosyl- (or fructosyl-) enzyme intermediate. In the second step, the glucosyl/fructosyl moiety is transferred to an acceptor with retention of the anomeric configuration (Leemhuis et al., 2013). Ozimek and colleagues (2006) illustrated the mode of action of fructansucrases based on the double-displacement reaction mechanism as it is shown in Fig. 4. The fructosyltransferase −1 subsite is highly specific for accommodating fructose units, whereas the +1 subsite seems to be more flexible, exhibiting affinity for both glucose (binding of sucrose, Fig. 4A) and fructose (binding sucrose as an acceptor substrate during transglycosylation, Fig. 4C). Consequently, sucrose enters the active site and occupies the −1 and +1 subsites, the glycosidic bond is cleaved as explained above, and a covalent fructosyl-enzyme intermediate is formed at −1 and glucose is released. Then, water may enter the active site, react with the fructosyl-enzyme intermediate, resulting in hydrolysis and release of fructose (Fig. 4B). Alternatively, a second acceptor substrate (sucrose) enters the active site, binds to the +1 and +2 subsites and reacts with the fructosyl-enzyme intermediate at −1, resulting in the oligosaccharide formation (i.e. fructo-oligosaccharides) (Fig. 4C). Further transglycosylation reaction may take place, resulting in chain elongation and polymer formation (Ozimek et al., 2006). Furthermore, it has been indicated that the amino acid residues responsible for the different product linkage type specificities of inulosucrase β(2→1) and levansucrase β(2→6) should orient the accepting fructosyl moiety at subsite +1 in quite different ways to form either of two types of glycosidic linkage (Pijning et al., 2011). These authors suggested that a non-conserved specific region of GH68 fructansucrases, i.e. the 1B–1C loop, could be involved in acceptor-binding interactions and determine the product specificity in bacterial fructansucrases.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the reaction sequences occurring in the active site of fructansucrase enzymes (FSs). The donor and acceptor subsites of FSs enzymes are mapped out based on the available three-dimensional structural information (Meng and Fütterer, 2003; Martínez-Fleites et al., 2005; Ozimek et al., 2006).A. Binding of sucrose to subsites −1 and +1 results in cleavage of the glycosidic bond (glucose released, shown in grey), and formation of a (putative) covalent intermediate at subsite −1 (indicated by a grey line). Depending on the acceptor substrate used, hydrolysis (by water) (B) or transglycosylation (C) reaction may occur [with oligosaccharides or the growing polymer chain, resulting in the synthesis of FOS (n + 1) or fructan polymer (n + 1), respectively]. Reprinted with permission from Ozimek et al. Copyright (2006) Society for General Microbiology.

Enzymatic synthesis of novel lactose-derived oligosaccharides

Although the enzymatic synthesis of bioactive carbohydrates from lactose have been extensively investigated to produce GOS, recent research has focused on enzymatic transglycosylation using lactulose or mixtures of lactose with other carbohydrates, developing new bioactive oligosaccharides varying in their monosaccharide composition and structural features as it will be explained below. During enzymatic hydrolysis of lactose in the presence of other carbohydrates, they can act as acceptors in the galactosylation process to give new β-linked galactosyl oligosaccharides (Li et al., 2009; Schuster-Wolff-Bühring et al., 2009; Seki and Saito, 2012). Lactose-derived oligosaccharides can also be produced during enzymatic hydrolysis of other carbohydrates using lactose as acceptor (Table 1).

Lactosucrose

Lactosucrose (O-β-D-galactopyranosyl-(1→4)-O-α-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-fructofuranoside), also named lactosylfructoside, is a non-reducing trisaccharide obtained from a mixture of lactose (β-D-galactopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-D-glucose) and sucrose (α-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-fructose) by enzymatic transglycosylation. Synthesis reaction may occur either by transfructosylation by β-fructofuranosidase (EC 3.2.1.26) from Arthrobacter sp. K-1 (Fujita et al., 1990; Mikuni et al., 2000; Pilgrim et al., 2001) or levansucrases (EC 2.4.1.10) from various bacteria strains such as Bacillus subtilis (Park et al., 2005), B. natto (Takahama et al., 1991), Paenibacillus polymyxa (Choi et al., 2004) and Zymomonas mobilis (Han et al., 2009), or through transgalactosylation by β-galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.23) from B. circulans (Li et al., 2009). In the first case (transfructosylation reaction), lactose acts as acceptor of the fructosyl moiety of sucrose whereas in the latter (transgalactosylation), lactose can act both as donor and acceptor so that a mixture of GOS are produced, in addition to lactosucrose, which is formed by transferring the galactosyl moiety from lactose to sucrose.

The first study reported in the literature on lactosucrose synthesis was undertaken by Avigad in 1957 who reported its production by levansucrase from Aerobacter levanicum. Subsequently, in the 1990's, lactosucrose industrial production was developed by Fujita and colleagues (1992). Since then, lactosucrose has been commercially produced by transglycosylation for over 20 years (Mu et al., 2013). It is used as a low-calorie sweetener because of being hardly hydrolyzed by human digestive enzymes or prebiotic ingredient because of its ability to enhance the growth of beneficial bifidobacteria and to maintain the balance of the intestinal environment (Yoneyama et al., 1992; Ogata et al., 1993; Ohkusa et al., 1995). Other healthy effects that have been linked to the ingestion of lactosucrose are the prevention of constipation and reduction of serum hyperlipidemia (Kitahata and Fujita, 1993; Côté, 2007).

Lactosucrose marketing has received particular interest in Japan where over 30 food products containing this prebiotic ingredient have been certified as food for specified health use, being Ensuiko Sugar Refining and Hayashibara Shoji the two major manufacturers. Besides Japan, lactosucrose is also marketed in the United States followed by Europe as it can be considered an emerging prebiotic (Crittenden, 2006; Rastall, 2010).

Galactooligosaccharides derived from lactulose (GOS-Lu)

Typical GOS comprises a complex mixture of carbohydrates obtained by transgalactosylation reactions from lactose using β-galactosidases of different origins. This complexity relies on a different chain length (normally from disaccharides to octasaccharides) and on the type of glycosidic linkages. The composition of GOS is normally highly affected by several factors including the enzyme source, lactose concentration, substrate composition and reaction conditions (temperature, pH, time and enzyme charge). Using lactose as a single substrate, the galactose released during enzymatic hydrolysis of lactose may be transferred to another lactose molecule, being linked to the galactose moiety by β(1→6), β(1→4) or β(1→3) glycosidic bonds, depending on the enzyme source. The trisaccharides formed may be elongated by new linked galactosyl moieties (Gänzle, 2012). The galactosyl residue may also be transferred to the glucose released to give allolactose (Mahoney, 1998).

In a series of pioneering works (Cardelle-Cobas et al., 2008; Martínez-Villaluenga et al., 2008b), the use of lactulose (4-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl-D-fructose) instead of lactose as precursor of novel GOS was proposed. The interest of this type of oligosaccharides could rely on the multiple beneficial properties that lactulose exhibits per se, and consequently, GOS produced from the straight transglycosylation of lactulose instead of lactose might possess an added value as compared to the conventional GOS. In this sense, lactulose is a synthetic disaccharide commercially produced by chemical isomerization of lactose under basic media (Mendez and Olano, 1979) and is recognized since the 1950's as a bifidogenic factor when added to the diet (Petuely, 1957). Lactulose is also efficient in the treatment of chronic constipation (Mayerhofer and Petuely, 1959) and to control portal-systemic encephalopathy (Bircher et al., 1966), a chronic disease state that caused elevated blood ammonia levels that interferes with brain functions, causing cognitive dysfunction and psychiatric disorders. Lactulose helps restore normal neurological function when fermented by colonic bacteria to short chain fatty acids that acidify the content of the large bowel resulting in the trapping and reabsorption of ammonia. Today, lactulose is used in medicine as well as in the food industry (Schumann, 2002).

Lactulose has indeed been demonstrated to be hydrolyzed by the action of β-galactosidases from different microbial origin, such as Kluyveromyces lactis (Martínez-Villaluenga et al., 2008b; Cardelle-Cobas et al., 2011a), Aspergillus aculeatus (Cardelle-Cobas et al., 2008), Aspergillus oryzae (Hernández-Hernández et al., 2011) and, albeit at a much lesser extent, Bacillus circulans (Corzo-Martínez et al., 2013). Consequently, lactulose can be used as a substrate for the efficient oligosaccharide synthesis during transglycosylation because the galactose released is transferred to another lactulose molecule leading to the formation of GOS-Lu, as well as to galactose and fructose monomers derived from the lactulose hydrolysis to give different galactobioses and galactosyl-fructoses as displayed in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

General scheme of transgalactosylation and hydrolytic processes involving lactulose and β-galactosidase to produce GOS-Lu, galactobioses and galactosyl-fructoses.

Similarly to GOS-derived from lactose, a complex mixture of GOS-Lu with different glycosidic linkages and molecular weights is obtained and the yield is affected by the ratio of hydrolytic and transferase activities of the enzyme. In a similar way to conventional GOS, this ratio depends mainly on the enzyme source, the concentration of initial lactulose and the reaction conditions (temperature, pH, time and enzyme charge). In general terms, the transferase activity is favoured at high initial lactulose concentration, elevated reaction temperature and lower water activity (Tzortzis and Vulevic, 2009), providing good yields in GOS-Lu. Table 3 summarizes the characterized carbohydrate composition of GOS-Lu resulting from the reaction mixtures using different enzymes, as well as the optimum conditions leading to the maximum levels of GOS-Lu. Optimum pH and temperature conditions are constrained by the source of enzyme, as well as the type of glycoside bond formed between the transferred galactose moieties and lactulose, galactose or fructose to give the different oligosaccharides. Concretely, β-galactosidases from Aspergillus sp. predominantly produced oligosaccharides with β(1→6) linkages, such as 6′-galactosyl-lactulose and, in lesser concentrations, 6-galactobiose and allolactulose, while β-galactosidase from K. lactis synthesized similar levels of 6′-galactosyl-lactulose and 1-galactosyl-lactulose (Table 3). In contrast, the main trisaccharide formed after the synthesis with a β-galactosidase from B. circulans was the 4′-galactosyl-lactulose, suggesting the preferential formation of β(1→4) glycosidic linkages, in good agreement with the findings described for the synthesis of GOS from the transgalactosylation of lactose (Rodríguez-Colinas et al., 2012).

Table 3.

Oligosaccharide composition and yield of GOS-Lu using different microbial β-galactosidases

| β-Galactosidase source | Optimum reaction conditions | Oligosaccharide composition | Total GOS-Lu yield | Main glycosidic linkage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kluyveromyces lactisa | 250 g l−1 Lactulose; 50°C; pH 7.5, 2 h | 31% Monosaccharides | 27% | β(1→6) β(1→1) |

| 42% Lactulose | ||||

| 10% 6′-Galactosyl-lactulose | ||||

| 11% 1-Galactosyl-lactulose | ||||

| 6% Unidentified oligosaccharides | ||||

| Aspergillus aculeatusa | 450 g l−1 Lactulose; 60°C; pH 6.5, 7 h | 35% Monosaccharides | 29% | β(1→6) |

| 36% Lactulose | ||||

| 15% 6′-Galactosyl-lactulose | ||||

| 2% 1-Galactosyl-lactulose | ||||

| 12% Unidentified oligosaccharides | ||||

| Aspergillus oryzaeb | 450 g l−1 Lactulose; 50°C; pH 6.5, 1 h | 30% Monosaccharides | 50% | β(1→6) |

| 20% Lactulose | ||||

| 20% 6′-Galactosyl-lactulose | ||||

| 3% 6-Galactobiose | ||||

| 1% Allolactulose | ||||

| 26% Unidentified oligosaccharides | ||||

| Bacillus circulansc | 300 g l−1 Lactulose; 50°C; pH 6.5, 5 h | 4′-Galactosyl-lactulosed | –d | β(1→4) |

Concerning GOS-Lu yields, although the quantification described in Table 3 was carried out from di-, tri- and tetrasaccharides, evidences on presence of penta- and hexasaccharides in minor amounts have been also reported (Hernández-Hernández et al., 2011). Thus, considering disaccharides (not including lactulose), tri- and tetrasaccharides, GOS-Lu yields ranged from 27% to 50%, with the β-galactosidase from A. oryzae providing the highest yield, whereas those of K. lactis and A. aculeatus showed lower transglycosylation activity (Table 3). β-Galactosidase from B. circulans showed an extremely low hydrolytic activity on lactulose and, therefore, only low levels of GOS-Lu could be determined (Corzo-Martínez et al., 2013).

Up to now, there are considerable in vitro and in vivo data supporting some remarkable beneficial effects of GOS-Lu, specially, on the gastrointestinal system. Thus, a preliminary in vitro study carried out with pure cultures of different probiotic bacteria showed that this type of oligosaccharide was fermented by different strain of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and Streptococcus (Cardelle-Cobas et al., 2011b). Later on, in vitro pH-controlled fermentation studies performed with human faecal samples demonstrated the bifidogenic activity of GOS-Lu (Cardelle-Cobas et al., 2009; 2012). Likewise, in vivo studies carried out with growing rats revealed a higher resistance of GOS-Lu to gastrointestinal digestion and absorption in the small intestine than that of GOS from lactose, which was attributed to the great resistance of galactosyl-fructoses to the hydrolytic action of mammalian digestive enzymes. These results highlight the key role played by the monomer type and glycosidic linkage involved in the oligosaccharide structure. In addition, the bifidogenic effect observed in in vitro studies was also corroborated by this in vivo assay with rats fed 1% (w/w) of GOS-Lu for 14 days (Hernández-Hernández et al., 2012). Furthermore, a significant and selective increase of Bifidobacterium animalis counts in the caecum and colon section of these rats was observed (Marín-Manzano et al., 2013). Taken together, these data clearly support the potential use of GOS-Lu as novel prebiotic ingredients as meet the three criteria that a food ingredient must satisfy to be considered as prebiotic: (i) non-digestibility, (ii) fermentation by the intestinal microbiota and (iii) a selective stimulation of the growth and/or activity of those intestinal bacteria that contribute to health and well-being. Nevertheless, because clinical trials are essential to make any claim of prebiotic properties, in vivo studies carried out with humans should be performed in order to definitively establish their prebiotic properties.

On the other hand, GOS-Lu has been also reported to exhibit in vitro immunomodulatory properties using intestinal (Caco-2) cells (Laparra et al., 2013). GOS-Lu inhibited the production of pro-inflammatory factors, such as necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 beta, by intestinal cells stimulated by the pathogen Listeria monocytogenes CECT 935. The authors suggested that GOS-Lu had the ability to impair the interaction of virulence factors of this intestinal pathogen with the epithelial cells.

Another beneficial activity associated to prebiotics is the increase in absorption of several minerals, such as calcium or magnesium, across the epithelial cells of colon and caecum (Gibson et al., 2004). In this context, GOS-Lu has been recently shown to improve iron absorption in an in vivo iron-deficient animal model carried out with Wistar rats (J.M. Laparra, M. Díez-Municio, M. Herrero and F.J. Moreno, unpublished).

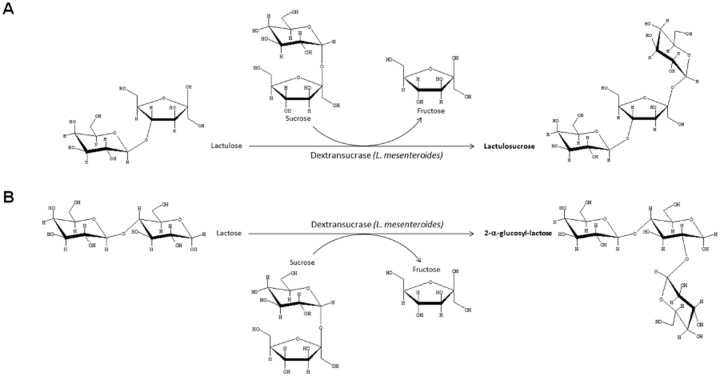

Lactulosucrose

Lactulose may also be used as glycosyl acceptor during enzymatic hydrolysis of other carbohydrates. This is of particular interest because it can expand the opportunities for the synthesis of new lactulose-derived oligosaccharides with novel structures and improved prebiotic properties. This approach has been used to prepare lactulose derivatives as lactulosucrose (β-D-galactopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-D-fructofuranosyl-(2→1)-α-D-glucopyranoside), a trisaccharide produced from the transfer of the glucosyl moiety of sucrose to the C-2 group of the reducing end unit of lactulose and catalyzed by a dextransucrase produced by Leuconostoc mesenteroides B-512F (Fig. 6A) (Díez-Municio et al., 2012a). Among the reaction parameters optimized, the concentration ratio of donor (sucrose) to acceptor (lactulose) and the dextransucrase charge had a considerable impact on the yield of lactulosucrose. From the reported results, it could be concluded that using the same concentration of dextransucrase, the higher the ratio of lactulose to sucrose, the higher the amount of synthesized lactulosucrose. Furthermore, in general terms, as the concentration of enzyme was increased, the levels of lactulosucrose were higher and achieved at shorter reaction times. The enzymatic reaction carried out under optimal conditions, i.e. at 30°C, pH 5.2 with a dextransucrase charge of 2.4 U ml−1 and a starting concentration of sucrose:lactulose 30:30 (expressed in g 100 ml−1) led to the production of lactulosucrose with a high yield of 35% in weight respect to the initial amount of lactulose. Likewise, this enzymatic reaction was also characterized by a high regioselectivity, which allowed the major formation of lactulosucrose, and only traces of other acceptor-reaction products susceptible to correspond to lactulose-based tetra- and pentasaccharide could be detected. This non-complex oligosaccharide pattern makes easier the isolation, as well as the potential scale-up of the manufacture process.

Fig. 6.

Process scheme for the synthesis of (A) lactulosucrose and (B) 2-α-glucosyl-lactose by transglucosylation of lactulose and lactose, respectively, catalyzed by a dextransucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides B-512F.

Concerning bioactive properties, preliminary data on selective fermentation of lactulosucrose by pure cultures of different probiotic bacteria have revealed a significant bifidogenic effect. In fact, three different bifidobacterial strains, B. lactis BB-12, B. breve 26 M2 and B. bifidum HDD541, grew better on lactulosucrose than on lactulose or lactosucrose (T. García-Cayuela, M. Díez-Municio, M. Herrero, M.C. Martínez-Cuesta, C. Peláez, T. Requena and F.J. Moreno, unpublished). In addition, having lactulose as a core structure, lactulosucrose might possess the beneficial properties attributed to lactulose, e.g. prebiotic activity, enhancement of mineral absorption, blood glucose-lowering effects and reduction in intestinal transit time, among others (Schumann, 2002). Also, lactulosucrose might possess lower fermentation rates as compared with lactulose because longer carbohydrate chains are normally fermented slower (Perrin et al., 2002). This would increase its interest as prebiotic by increasing its capacity to reach the distal parts of the colon, where many chronic gut disorders take place (Gibson et al., 2004). In summary, lactulosucrose could be an emerging bioactive oligosaccharide with interesting food and/or pharmaceutical applications.

2-α-Glucosyl-lactose

Similarly to the enzymatic synthesis of lactulosucrose, lactose has also proven to be an efficient acceptor in the L. mesenteroides B-512F dextransucrase-catalyzed reaction using sucrose as a donor. This enzyme catalyzes the transfer of glucose released from the hydrolysis of sucrose to the 2-hydroxyl group of the reducing glucose unit of lactose to form the trisaccharide 2-α-glucosyl-lactose (Fig. 6B) (Díez-Municio et al., 2012b). In this case, the effect of synthesis conditions, including concentration of substrates, molar ratio of donor/acceptor, enzyme concentration, reaction time and temperature were also evaluated and optimized. This trisaccharide was produced not only from buffered lactose solution, but also from several industrial cheese whey permeates. In all cases, 2-α-glucosyl-lactose was produced with high regioselectivity and excellent yields, reaching values up to 47% (when using lactose solutions) and 52%, in weight respect to the initial amount of lactose, when cheese whey permeate was used as starting material. It was hypothesized that the mineral composition contained in the studied cheese whey permeates (including the trace minerals) might have an effect on the transfer rate of the dextransucrase and, therefore, on the content of 2-α-glucosyl-lactose, in a similar way to the effect of different cations, such as sodium, potassium and magnesium had on the transgalactosylation activity of several fungal and bacterial β-galactosidases (Garman et al., 1996; Montilla et al., 2012).

According to the elucidated structure (Fig. 6B), this trisaccharide could also be a suitable candidate for a new prebiotic ingredient because the reported high resistance of α(1→2) linkages to the digestive enzymes in humans and animals (Valette et al., 1993; Remaud-Simeon et al., 2000) as well as to its potential selective stimulation of beneficial bacteria in the large intestine mainly attributed to the two linked glucose units located at the reducing end that reflects the disaccharide kojibiose (2-α-D-glucopyranosyl-D-glucose) (Nakada et al., 2003; Sanz et al., 2005). In fact, 2-α-glucosyl-lactose has been recently used as an efficient precursor for the enzymatic synthesis of kojibiose following its hydrolysis with a β-galactosidase from K. lactis and further purification (Díez-Municio et al., 2013a; 2014). Kojibiose is a naturally occurring disaccharide present in honey, beer or sake, although at low levels, which makes difficult its isolation from natural sources at high scale. Apart from the prebiotic properties attributed to kojibiose, important potential pharmaceutical applications have been also linked to this particular disaccharide (Srivastava et al., 2011).

Conclusions

The development of simple and convenient methods for the efficient synthesis of bioactive oligosaccharides offers opportunities to facilitate their use as functional ingredients. In general, the use of microbial glycoside hydrolase enzymes have a great potential in the food carbohydrate field, as they normally exhibit high substrate specificity, regio- and stereospecificity, and can be economically produced. This review has addressed the suitability of lactose in the presence or absence of sucrose to act as precursor for the high-yield synthesis of novel and potentially functional dietary oligosaccharides. Lactose, sucrose and their corresponding agro-industrial by-products containing these disaccharides, such as beet and cane molasses or cheese whey permeate, share the characteristic of being derived from readily available and inexpensive raw materials. These facts could contribute to the development of efficient and inexpensive manufacturing process of promising functional oligosaccharides, which could exert a series of beneficial properties on host health.

Lastly, engineering selected enzymes by site-directed mutagenesis studies could provide new mutants with different specificity (e.g. improved transglycosylation activities) and, thus, guide the transglycosylation reaction towards the synthesis of tailor-made oligosaccharides of specific interest for human health. The search of new microbial enzyme sources could also contribute to the production of novel oligosaccharides with new and/or improved bioactive and physico-chemical properties.

Acknowledgments

M.D.-M. thanks CSIC for a JAE predoctoral fellowship co-funded by European Social Fund (ESF). M.H. thanks MICINN for his ‘Ramón y Cajal’ contract.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- André I, Potocki-Véronèse G, Morel S, Monsan P, Remaud-Simeon M. Sucrose-utilizing transglucosidases for biocatalysis. Top Curr Chem. 2010;294:25–48. doi: 10.1007/128_2010_52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avigad G. Enzymatic synthesis and characterization of a new trisaccharide, α-lactosyl-β-fructofuranoside. J Biol Chem. 1957;229:121–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bircher J, Müller J, Guggenheim P, Haemmerli UP. Treatment of chronic portal-systemic encephalopathy with lactulose. Lancet. 1966;1:890–892. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)91573-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brás NF, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ. QM/MM studies on the β-galactosidase catalytic mechanism: hydrolysis and transglycosylation reactions. J Chem Theory Comput. 2010;6:421–433. doi: 10.1021/ct900530f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brison Y, Pijning T, Malbert Y, Fabre É, Mourey L, Morel S, et al. Functional and structural characterization of α-(1–2) branching sucrase derived from DSR-E glucansucrase. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:7915–7924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz K, Seibel J. Industrial carbohydrate biotransformations. Carbohydr Res. 2008;343:1966–1979. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canedo M, Jimenez-Estrada M, Cassani J, López-Munguia A. Production of maltosylfructose (erlose) with levansucrase from Bacillus subtilis. Biocatal Biotransform. 1999;16:475–485. [Google Scholar]

- Cardelle-Cobas A. 2009. Síntesis, caracterización y estudio del carácter prebiótico de oligosacáridos derivados de la lactulosa. PhD Thesis. Madrid, Spain: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

- Cardelle-Cobas A, Martínez-Villaluenga C, Villamiel M, Olano A, Corzo N. Synthesis of oligosaccharides derived from lactulose and pectinex ultra SP-L. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:3328–3333. doi: 10.1021/jf073355b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardelle-Cobas A, Fernández M, Salazar N, Martínez-Villaluenga C, Villamiel M, Ruas-Madiedo P, de los Reyes-Gavilán CG. Bifidogenic effect and stimulation of short chain fatty acid production in human faecal slurry cultures by oligosaccharides derived from lactose and lactulose. J Dairy Res. 2009;76:317–325. doi: 10.1017/S0022029909004063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardelle-Cobas A, Corzo N, Martinez-Villaluenga C, Olano A, Villamiel M. Effect of reaction conditions on lactulose-derived trisaccharides obtained by transgalactosylation with β-galactosidase of Kluyveromyces lactis. Eur Food Res Technol. 2011a;233:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cardelle-Cobas A, Corzo N, Olano A, Peláez C, Requena T, Ávila M. Galactooligosaccharides derived from lactose and lactulose: influence of structure on LactobacillusStreptococcus and Bifidobacterium growth. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011b;149:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardelle-Cobas A, Olano A, Corzo N, Villamiel M, Collins M, Kolida S, Rastall RA. In vitro fermentation of lactulose-derived oligosaccharides by mixed fecal microbiota. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:2024–2032. doi: 10.1021/jf203622d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casci T, Rastall RA. Manufacture of prebiotic oligosaccharides. In: Gibson GR, Rastall RA, editors. Prebiotics: Development and Application. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. pp. 29–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Wang L, Jiang YL, Bai XH, Chu J, Li Q, et al. Structural insights into the substrate specificity of Streptococcus pneumoniae β(1,3)-galactosidase BgaC. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22910–22918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.367128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H-J, Kim CS, Kim P, Jung H-C, Oh D-K. Lactosucrose bioconversion from lactose and sucrose by whole cells of Paenibacillus polymyxa harboring levansucrase activity. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20:1876–1879. doi: 10.1021/bp049770v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuankhayan P, Hsieh CY, Huang YC, Hsieh YY, Guan HH, Hsieh YC, et al. Crystal structures of Aspergillus japonicus fructosyltransferase complex with donor/acceptor substrates reveal complete subsites in the active site for catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:23251–23264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.113027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CH, Day DF. Glucooligosaccharides from Leuconostoc mesenteroides B-742 (ATCC 13146): a potential prebiotic. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;29:196–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenen GJ, Kabel MA, Schols HA, Voragen AG. CE-MSn of complex pectin-derived oligomers. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:2101–2111. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corzo-Martínez M, Copoví P, Olano A, Moreno FJ, Montilla A. Synthesis of prebiotic carbohydrates derived from cheese whey permeate by a combined process of isomerisation and transgalactosylation. J Sci Food Agric. 2013;93:1591–1597. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho PM, Deleury E, Davies GJ, Henrissat B. An evolving hierarchical family classification for glycosyltransferases. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté GL. Flavorings and other value-added products from sucrose. In: Rastall RA, editor. Novel enzyme technology for food applications. Boca Ratón, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 243–269. [Google Scholar]

- Côté GL. Oligosaccharides from sucrose via glycansucrases. In: Gordon NS, editor. Oligosaccharides: Sources, Properties and Applications. Hauppage, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2011. pp. 157–179. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden R. Emerging prebiotic carbohydrates. In: Gibson GR, Rastall RA, editors. Prebiotics: Development & Application. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2006. pp. 111–133. [Google Scholar]

- Davies G, Henrissat B. Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases. Structure. 1995;3:853–859. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies GJ, Wilson KS, Henrissat B. Nomenclature for sugar-binding subsites in glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem J. 1997;321:557–559. doi: 10.1042/bj3210557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Municio M, Herrero M, Jimeno ML, Olano A, Moreno FJ. Efficient synthesis and characterization of lactulosucrose by Leuconostoc mesenteroides B-512F dextransucrase. J Agric Food Chem. 2012a;60:10564–10571. doi: 10.1021/jf303335m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Municio M, Montilla A, Jimeno ML, Corzo N, Olano A, Moreno FJ. Synthesis and characterization of a potential prebiotic trisaccharide from cheese whey permeate and sucrose by Leuconostoc mesenteroides dextransucrase. J Agric Food Chem. 2012b;60:1945–1953. doi: 10.1021/jf204956v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Municio M, Moreno FJ, Herrero M, Montilla A. 2013a. Procedimiento de síntesis de kojibiosa y su aplicación en la elaboración de composiciones alimentarias y farmaceúticas. Spanish Patent P201331333.

- Díez-Municio M, de las Rivas B, Jimeno ML, Muñoz R, Moreno FJ, Herrero M. Enzymatic synthesis and characterization of fructooligosaccharides and novel maltosylfructosides by inulosucrase from Lactobacillus gasseri DSM 20604. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013b;79:4129–4140. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00854-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Municio M, Montilla A, Moreno FJ, Herrero M. A sustainable biotechnological process for the efficient synthesis of kojibiose. Green Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1039/C3GC42246A; In press. [Google Scholar]

- Filice M, Marciello M. Enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharides: a powerful tool for a sweet challenge. Curr Org Chem. 2013;17:701–718. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto Y, Hattori T, Uno S, Murata T, Usui T. Enzymatic synthesis of gentiooligosaccharides by transglycosylation with beta-glycosidases from Penicillium multicolor. Carbohydr Res. 2009;344:972–978. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K, Hara K, Hashimoto H, Kitahata S. Transfructosylation catalyzed by β-fructofuranosidase I from Arthrobacter sp. K-1. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:2655–2661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K, Hara K, Hashimoto H, Kitahata S. 1992. Method for the preparation of fructose-containing oligosaccharide. US Patent 5,089,401. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Garman J, Coolbear T, Smart J. The effect of cations on the hydrolysis of lactose and the transferase reactions catalysed by β-galactosidase from six strains of lactic acid bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;46:22–27. doi: 10.1007/s002530050778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gänzle MG. Enzymatic synthesis of galacto-oligosaccharides and other lactose derivatives (hetero-oligosaccharides) from lactose. Int Dairy J. 2012;22:116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson GR, Roberfroid MB. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. J Nutr. 1995;125:1401–1412. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson GR, Probert HM, Loo JV, Rastall RA, Roberfroid MB. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: updating the concept of prebiotics. Nutr Res Rev. 2004;17:259–275. doi: 10.1079/NRR200479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster TM, Roberts S, Ducros VM, Perugino G, Rossi M, Hoos R, et al. Structural studies of the β-glycosidase from Sulfolobus solfataricus in complex with covalently and noncovalently bound inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6101–6109. doi: 10.1021/bi049666m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffin D, Delzenne N, Blecker C, Hanon E, Deroanne C, Paquot M. Will isomalto-oligosaccharides, a well-established functional food in Asia, break through the European and American market? The status of knowledge on these prebiotics. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2011;51:394–409. doi: 10.1080/10408391003628955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung N, Ray S, Bose S, Rai V. A broader view: microbial enzymes and their relevance in industries, medicine, and beyond. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:329121. doi: 10.1155/2013/329121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W-C, Byun S-H, Kim M-H, Sohn EH, Lim JD, Um BH, et al. Production of lactosucrose from sucrose and lactose by a levansucrase from Zymomonas mobilis. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;19:1153–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino-acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1991;280:309–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B, Davies G. Structural and sequence-based classification of glycoside hydrolases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:637–644. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Hernández O, Montañés F, Clemente A, Moreno FJ, Sanz ML. Characterization of galactooligosaccharides derived from lactulose. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218:7691–7696. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Hernández O, Marín-Manzano MC, Rubio LA, Moreno FJ, Sanz ML, Clemente A. Monomer and linkage type of galacto-oligosaccharides affect their resistance to ileal digestion and prebiotic properties in rats. J Nutr. 2012;142:1232–1239. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.155762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka M, Fushinobu S, Ohtsu N, Motoshima H, Matsuzawa H, Shoun H, Wakagi T. Trimeric crystal structure of the glycoside hydrolase family 42 beta-galactosidase from Thermus thermophilus A4 and the structure of its complex with galactose. J Mol Biol. 2002;322:79–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00746-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hijum SA, Kralj S, Ozimek LK, Dijkhuizen L, van Geel-Schutten IG. Structure-function relationships of glucansucrase and fructansucrase enzymes from lactic acid bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:157–176. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.157-176.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holck J, Hjerno K, Lorentzen A, Vigsnaes LK, Hemmingsen L, Licht TR, et al. Tailored enzymatic production of oligosaccharides from sugar beet pectin and evidence of differential effects of a single DP chain length difference on human faecal microbiota composition after in vitro fermentation. Process Biochem. 2011;46:1039–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Irague R, Tarquis L, André I, Moulis C, Morel S, Monsan P, et al. Combinatorial engineering of dextransucrase specificity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e77837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Ito S, Shimamura T, Weyand S, Kawarasaki Y, Misaka T, et al. Crystal structure of glucansucrase from the dental caries pathogen Streptococcus mutans. J Mol Biol. 2011;408:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juers DH, Jacobson R, Wigley D, Zhang X, Huber RE, Tronrud DE, Matthews BW. High resolution refinement of β-galactosidase in a new crystal form reveals multiple metal-binding sites and provides a structural basis for alpha-complementation. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1685–1699. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-M, Kang H-K, Moon Y-H, Nguyen TTH, Day DF, Kim D. Production and bioactivity of glucooligosaccharides and glucosides synthesized using glucansucrases. In: Moreno FJ, Sanz ML, editors. Food Oligosaccharides: Production, Analysis and Bioactivity. Chichester, England: Wiley Blackwell; 2014. pp. 168–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kitahata S, Fujita K. Xylsucrose, isomaltosucrose and lactosucrose. In: Nakakuki T, editor. Oligosaccharides: Production, Properties and Applications. Yverdon, Switzerland: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers; 1993. pp. 158–174. [Google Scholar]

- Koshland DE. Stereochemistry and the mechanism of enzymatic reactions. Biol Rev. 1953;28:416–436. [Google Scholar]

- Laparra JM, Hernández-Hernández O, Moreno FJ, Sanz Y. Neoglycoconjugates of caseinomacropeptide and galactooligosaccharides modify adhesion of intestinal pathogens and inflammatory response(s) of intestinal (Caco-2) cells. Food Res Int. 2013;54:1096–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Leemhuis H, Pijning T, Dobruchowska JM, van Leeuwen SS, Kralj S, Dijkstra BW, Dijkhuizen L. Glucansucrases: three-dimensional structures, reactions, mechanism, α-glucan analysis and their implications in biotechnology and food applications. J Biotechnol. 2013;163:250–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Xiang XL, Tang SF, Hu B, Tian L, Sun Y, et al. Effective enzymatic synthesis of lactosucrose and its analogues by β-D-galactosidase from Bacillus circulans. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:3927–3933. doi: 10.1021/jf9002494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard V, Golaconda Ramulu H, Drula E, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. The Carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D490–D495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney RR. Galactosyl-oligosaccharide formation during lactose hydrolysis: a review. Food Chem. 1998;63:147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Maksimainen M, Hakulinen N, Kallio JM, Timoharju T, Turunen O, Rouvinen J. Crystal structures of Trichoderma reesei β-galactosidase reveal conformational changes in the active site. J Struct Biol. 2011;174:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksimainen M, Paavilainen S, Hakulinen N, Rouvinen J. Structural analysis, enzymatic characterization, and catalytic mechanisms of β-galactosidase from Bacillus circulans sp. alkalophilus. FEBS J. 2012;279:1788–1798. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksimainen MM, Lampio A, Mertanen M, Turunen O, Rouvinen J. The crystal structure of acidic β-galactosidase from Aspergillus oryzae. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013;60:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Manzano MC, Abecia L, Hernández-Hernández O, Sanz ML, Montilla A, Olano A, et al. Galacto-oligosaccharides derived from lactulose exert a selective stimulation on the growth of Bifidobacterium animalis in the large intestine of growing rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:7560–7567. doi: 10.1021/jf402218z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Fleites C, Ortíz-Lombardía M, Pons T, Tarbouriech N, Taylor EJ, Arrieta JG, et al. Crystal structure of levansucrase from the Gram-negative bacterium Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus. Biochem J. 2005;390:19–27. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Villaluenga C, Cardelle-Cobas A, Corzo N, Olano A, Villamiel M. Optimization of conditions for galactooligosaccharide synthesis during lactose hydrolysis by β-galactosidase from Kluyveromyces lactis (Lactozym 3000 L HP G) Food Chem. 2008a;107:258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Villaluenga C, Cardelle-Cobas A, Olano A, Corzo N, Villamiel M, Jimeno ML. Enzymatic synthesis and identification of two trisaccharides produced from lactulose by transgalactosylation. J Agric Food Chem. 2008b;56:557–563. doi: 10.1021/jf0721343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayerhofer F, Petuely F. Untersuchungen zur regula-tion der darmtatigkeit des erwachsenen mit hiefe der laktulose (bifidus-factor) Wien Klin Wschr. 1959;71:865–869. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez A, Olano A. Lactulose. A review of some chemical properties and applications in infant nutrition and medicine. Dairy Sci Abstr. 1979;41:531–535. [Google Scholar]

- Meng G, Fütterer K. Structural framework of fructosyl transfer in Bacillus subtilis levansucrase. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:935–941. doi: 10.1038/nsb974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikuni K, Wang Q, Fujita K, Hara K, Yoshida S, Hashimoto H. Continuous production of 4G-β-D-galactosylsucrose (lactosucrose) using immobilized β-fructofuranosidase. J Appl Glycosci. 2000;47:281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Monsan P, Paul F. Enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharides. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;16:187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Montilla A, Corzo N, Olano A. Effects of monovalent cations (Na+ and K+) on galacto-oligosaccharides production during lactose hydrolysis by Kluyveromyces lactis beta-galactosidase. Milchwiss-Milk Sci Int. 2012;67:14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mu W, Chen Q, Wang X, Zhang T, Jiang B. Current studies on physiological functions and biological production of lactosucrose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:7073–7080. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada T, Nishimoto T, Chaen H, Fukuda S. Kojioligosaccharides: application of kojibiose phosphorylase on the formation of various kojioligosaccharides. Oligosaccharides in food and agriculture. In Oligosaccharides. In: Eggleston G, Côté GL, editors. Food and Agriculture. ACS Symposium Series. Washington, DC, USA: American Chemical Society; 2003. pp. 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- OECD-FAO. 2013. Agricultural Outlook 2013–2022. URL http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/agriculture-and-food/oecd-fao-agricultural-outlook-2013/cheese-projections-consumption-per-capita_agr_outlook-2013-Table208-en.

- Ogata Y, Fujita K, Ishigami H, Hara K, Terada A, Hara H, et al. Effect of a small amount of 4G-β-D-galactosylsucrose (lactosucrose) on fecal flora and fecal properties. J Jpn Soc Nutr Food Sci. 1993;4:317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Ohkusa T, Ozaki Y, Sato C, Mikuni K, Ikeda H. Longterm ingestion of lactosucrose increases Bifidobacterium sp. in human fecal flora. Digestion. 1995;56:415–420. doi: 10.1159/000201269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olano-Martin E, Mountzouris KC, Gibson GR, Rastall RA. Continuous production of pectic oligosaccharides in an enzyme membrane reactor. J Food Sci. 2001;66:966–971. [Google Scholar]

- Ozimek LK, Kralj S, van der Maarel MJ, Dijkhuizen L. The levansucrase and inulosucrase enzymes of Lactobacillus reuteri 121 catalyse processive and non-processive transglycosylation reactions. Microbiology. 2006;152:1187–1196. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28484-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panesar PS, Panesar R, Singh RS, Kennedy JF, Kumar H. Microbial production, immobilization and applications of β-D-galactosidase. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2006;81:530–543. [Google Scholar]

- Park NH, Choi HJ, Oh DK. Lactosucrose production by various microorganisms harboring levansucrase activity. Biotechnol Lett. 2005;27:495–497. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-2539-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Rodríguez A, Fernández-Leiro R, González-Siso MI, Cerdán ME, Becerra M, Sanz-Aparicio J. Structural basis of specificity in tetrameric Kluyveromyces lactis β-galactosidase. J Struct Biol. 2012;177:392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin S, Fougnies C, Grill JP, Jacobs H, Schneider F. Fermentation of chicory fructo-oligosaccharides in mixtures of different degrees of polymerization by three strains of bifidobacteria. Can J Microbiol. 2002;48:759–763. doi: 10.1139/w02-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petuely F. The bifidus factor. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1957;82:1957–1960. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1117025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijning T, Anwar MA, Böger M, Dobruchowska JM, Leemhuis H, Kralj S, et al. Crystal structure of inulosucrase from Lactobacillus: insights into the substrate specificity and product specificity of GH68 fructansucrases. J Mol Biol. 2011;412:80–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijning T, Vujičić-Žagar A, Kralj S, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra BW. Structure of the α-1,6/α-1,4-specific glucansucrase GTFA from Lactobacillus reuteri 121. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2012;68:1448–1454. doi: 10.1107/S1744309112044168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim A, Kawase M, Ohashi M, Fujita K, Murakami K, Hashimoto K. Reaction kinetics and modelling of the enzyme-catalyzed production of lactosucrose using β-fructofuranosidase from Arthrobacter sp K-1. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001;65:758–765. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plou FJ, Martín MT, Gómez de Segura A, Alcalde M, Ballesteros A. Glucosyltransferases acting on starch or sucrose for the synthesis of oligosaccharides. Can J Chem. 2002;80:743–752. [Google Scholar]

- Plou FJ, Gómez de Segura A, Ballesteros A. Application of glycosidases and transglycosidases in the synthesis of oligosaccharides. In: Polaina J, MacCabe AP, editors. Industrial Enzymes: Structure, Function and Applications. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2007. pp. 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Zhang Y, He H, Zhu J, Chen G, Li W, Liang Z. Screening and identification of a fungal β-glucosidase and the enzymatic synthesis of gentiooligosaccharide. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;163:1012–1019. doi: 10.1007/s12010-010-9105-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastall RA. Functional oligosaccharides: application and manufacture. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2010;1:305–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.food.080708.100746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remaud M, Paul F, Monsan P. Characterization of α-1,3 branched oligosaccharides synthesized by acceptor reaction with the extracellular glucosyltransferases from Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-742. J Carbohydr Chem. 1992;11:359–378. [Google Scholar]

- Remaud-Simeon M, Willemot RM, Sarçabal P, Potocki de Montalk G, Monsan P. Glucansucrases: molecular engineering and oligosaccharide synthesis. J Molec Catal B: Enzym. 2000;10:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Robyt JF, Yoon SH, Mukerjea R. Dextransucrase and the mechanism for dextran biosynthesis. Carbohydr Res. 2008;343:3039–3048. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Colinas B, Poveda A, Jiménez-Barbero J, Ballesteros AO, Plou FJ. Galacto-oligosaccharide synthesis from lactose solution or skim milk using the β-galactosidase from Bacillus circulans. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:6391–6398. doi: 10.1021/jf301156v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas AL, Nagem RA, Neustroev KN, Arand M, Adamska M, Eneyskaya EV, et al. Crystal structures of beta-galactosidase from Penicillium sp. and its complex with galactose. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:1281–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangeetha PT, Ramesh MN, Prapulla SG. Recent trends in the microbial production, analysis and application of fructooligosaccharides. Trends Food Sci Tech. 2005;16:442–457. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz ML, Gibson GR, Rastall RA. Influence of disaccharide structure on prebiotic selectivity in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:5192–5199. doi: 10.1021/jf050276w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann C. Medical, nutritional and technological properties of lactulose. An update. Eur J Nutr. 2002;41:17–25. doi: 10.1007/s00394-002-1103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster-Wolff-Bühring R, Jaindl K, Fischer L, Hinrichs J. A new way to refine lactose: enzymatic synthesis of prebiotic lactulose. Eur Dairy Mag. 2009;21:25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Seki N, Saito H. Lactose as a source for lactulose and other functional lactose derivatives. Int Dairy J. 2012;22:110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Skalova T, Dohnálek J, Spiwok V, Lipovová P, Vondrácková E, Petroková H, et al. Cold-active beta-galactosidase from Arthrobacter sp. C2-2 forms compact 660 kDa hexamers: crystal structure at 1.9A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:282–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro MD, Kates KA, Koller AL, Oneill MA, Albersheim P, Darvill AG. Purification and characterization of biologically-active 1,4-linked alpha-deuterium-oligogalacturonides after partial digestion of polygalacturonic acid with endopolygalacturonase. Carbohydr Res. 1993;247:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava O, Szweda R, Spohr U. 1996. Modified kojibiosides analogues. European Patent 0,830,365 B1.

- Strube CP, Homann A, Gamer M, Jahn D, Seibel J, Heinz DW. Polysaccharide synthesis of the levansucrase SacB from Bacillus megaterium is controlled by distinct surface motifs. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17593–17600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.203166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahama A, Kuze J, Okano S, Akiyama K, Nakane T, Takahashi H, Kobayashi T. Production of lactosucrose by Bacillus natto levansucrase and some properties of the enzyme. J Jpn Soc Nutr Food Sci. 1991;38:789–796. [Google Scholar]

- Torres DPM, Gonçalves MPF, Teixeira JA, Rodrigues LR. Galacto-oligosaccharides: production, properties, applications, and significance as prebiotics. Compreh Rev Food Sci Food Safety. 2010;9:438–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzortzis G, Vulevic J. Galacto-oligosaccharide prebiotics. In: Charalampopoulos D, Rastall RA, editors. Prebiotics and Probiotics Science and Technology. Vol. 1. New York, NY, USA: Springer Science+Business Media; 2009. pp. 207–244. [Google Scholar]

- Valette P, Pelenc V, Djouzi Z, Andrieux C, Paul F, Monsan P, Szylit O. Bioavailability of new synthesised glucooligosaccharides in the intestinal tract of gnotobiotic rats. J Sci Food Agric. 1993;62:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Vujičić-Žagar A, Pijning T, Kralj S, López CA, Eeuwema W, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra BW. Crystal structure of a 117 kDa glucansucrase fragment provides insight into evolution and product specificity of GH70 enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21406–21411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007531107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers SG. Mechanisms of glycosyl transferases and hydrolases. Carbohydr Polym. 2001;44:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama M, Mandai T, Aga H, Fujii K, Sakai S, Shintani T, et al. Effect of lactosucrose feeding on cecal pH, shortchain fatty acid concentration and microflora in rats. J Jpn Soc Nutr Food Sci. 1992;45:109–115. [Google Scholar]