Abstract

Objective

The aim of the current study was to identify individual characteristics that (1) predict symptom improvement with group cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for social anxiety disorder (SAD; i.e., prognostic variables) or (2) moderate the effects of d-cycloserine vs. placebo augmentation of CBT for SAD (i.e., prescriptive variables).

Method

Adults with SAD (N=169) provided Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) scores in a trial evaluating DCS augmentation of group CBT. Rate of symptom improvement during therapy and posttreatment symptom severity were evaluated using multilevel modeling. As predictors of these two parameters, we selected the range of variables assessed at baseline (demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, personality traits). Using step-wise analyses, we first identified prognostic and prescriptive variables within each of these domains and then entered these significant predictors simultaneously in one final model.

Results

African American ethnicity and cohabitation status were associated with greater overall rates of improvement during therapy and lower posttreatment severity. Higher initial severity was associated with a greater improvement during therapy, but also higher posttreatment severity (the greater improvement was not enough to overcome the initial higher severity). D-cycloserine augmentation was evident only among individuals low in conscientiousness and high in agreeableness.

Conclusions

African American ethnicity, cohabitation status, and initial severity are prognostic of favorable CBT outcomes in SAD. D-cycloserine augmentation appears particularly useful for patients low in conscientiousness and high in agreeableness. These findings can guide clinicians in making decisions about treatment strategies and can help direct research on the mechanisms of these treatments.

Keywords: Cognitive-behavioral therapy, d-cycloserine, CBT, social anxiety disorder, social phobia, randomized controlled trial, predictors, moderators, personality traits

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is among the most common anxiety disorders (Kessler et al., 2005). Epidemiological surveys further show that SAD, and particularly the generalized subtype, is associated with significant personal and societal costs (Schneier et al., 1994; Schneier, Johnson, Hornig, Liebowitz, & Weissman, 1992), underscoring the need for effective interventions. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been established as an efficacious intervention for SAD (Hofmann & Smits, 2008). CBT emphasizes repeated or prolonged confrontation to feared cues often in combination with cognitive restructuring (Hofmann & Otto, 2008), with the goal of assisting patients in reacquiring a sense of safety in social interaction and performance situations (Otto, Smits, & Reese, 2004). CBT, delivered in individual or group format, has been shown to outperform both pill and psychological placebo treatment (Davidson et al., 2004; Heimberg et al., 1998) and yields medium to large reductions in symptom severity (Clark et al., 2003). Although efficacious, CBT results in suboptimal outcomes for many. Indeed, treatment non-response rates in large clinical trials have been 50% or higher (Davidson et al., 2004), and most individuals do not achieve remission (Blanco et al., 2010; Davidson et al., 2004).

The observation of suboptimal outcomes of CBT for SAD has prompted research on augmentation strategies. One exciting development in this area has been the application of dcycloserine (DCS), a partial agonist at the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor (Anderson & Insel, 2006; Davis, Ressler, Rothbaum, & Richardson, 2006; Hofmann, Smits, Asnaani, Gutner, & Otto, 2011). Following preclinical research demonstrating that DCS can facilitate extinction learning in rodents by enhancing NMDA receptor function (Davis et al., 2006), initial studies of DCS for augmenting exposure therapy for the anxiety disorders have yielded promising results (Bontempo, Panza, & Bloch, 2012). With respect to SAD, Hofmann and colleagues (Hofmann, Meuret, et al., 2006) initially showed that patients receiving DCS 1 hour prior to the last 4 sessions of a 5-session CBT protocol evidenced significantly greater rates of improvement than patients who received pill placebo. This finding was later replicated by an independent group (Guastella, 2008). Given these positive findings, DCS as an augmentation strategy was subsequently applied to a standard 12-session course of group CBT for SAD, examining the degree to which it extends treatment gains in a full rather than an abbreviated protocol (Hofmann et al., in press)

As has been the case for CBT as a single modality treatment, response to DCS-augmented CBT has been variable across individuals with SAD (Hofmann, Pollack, & Otto, 2006; Hofmann et al., in press). The aim of the present study is to identify individual characteristics that differentiate response to DCS augmentation in a large-scale clinical trial comparing DCS-augmented group CBT to placebo-augmented group CBT in medication-free adults with generalized SAD (Hofmann et al., in press). In the context of this study, individual characteristics associated with differences in outcome between the experimental and the control condition are considered moderators (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002) or prescriptive variables (Fournier et al., 2009), whereas individual characteristics associated with outcome regardless of study condition are considered predictor or prognostic variables (Fournier et al., 2009). Accordingly, in addition to identifying individual characteristics that differentiate responding to DCS, this analysis has the potential to identify individual characteristics that are prognostic of responding to CBT for SAD regardless of DCS augmentation. We hope that the findings of this study will stimulate research aiming to refine the understanding of the mechanisms by which CBT (with or without DCS) reduces anxiety pathology, and thereby aid in achieving the goal of personalized therapy (Anderson & Insel, 2006).

Constrained by the limitations of the assessment protocol for the parent trial, we evaluated the patient characteristics available in our database that are also routinely assessed in clinical practice (e.g., demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and personality traits). Research relating the efficacy of DCS augmentation to these patient characteristics is limited to some preliminary work in PTSD. De Kleine and colleagues (de Kleine, Hendriks, Kusters, Broekman, & van Minnen, 2012) recently reported that differences between DCS-augmented CBT and placebo-augmented CBT with respect to symptom reduction were greater among patients who presented with more severe symptoms than patients who presented with less severe symptoms at baseline. However, because this post-hoc moderator analysis did not include any covariates, it is impossible to rule out possible third-variable explanations for the clinical severity-DCS efficacy relation observed in this study (e.g., comorbid diagnoses, sex, neuroticism, etc.).

Extant research on the relation between patient characteristics and CBT outcome for SAD has frequently pointed to depression severity as an important predictor (i.e., prognostic factor), although the findings have been mixed. Specifically, baseline depression severity has been associated with greater symptom severity at the end of CBT for SAD (Collimore & Rector, 2012; Erwin, Heimberg, Juster, & Mindlin, 2002; Ledley et al., 2005; Turner, Beidel, Wolff, Spaulding, & Jacob, 1996) and with less symptom improvement during CBT (Chambless, Tran, & Glass, 1997; Ledley et al., 2005). Several studies have, however, failed to observe the relation between depression and rate of change during CBT for SAD (Erwin et al., 2002; Joormann, Kosfelder, & Schulte, 2005; Turner et al., 1996), suggesting that baseline depression severity may simply be associated with greater symptom severity before and after treatment, but not necessarily the efficacy of CBT for SAD. Interestingly, McEvoy and colleagues (McEvoy, Nathan, Rapee, & Campbell, 2012) did not identify comorbid depression as a predictor of CBT for SAD outcome in an analysis that also included a number of other individual characteristic variables (e.g., age, gender, social anxiety symptom severity, number of comorbid diagnosis, degree of life interference). Instead, social anxiety symptom severity and number of comorbid diagnosis emerged as prognostic factors in this analysis. Together, these findings highlight the importance of evaluating multiple prospective prognostic or prescriptive variables simultaneously rather than in isolation.

Although it has been proposed that personality traits have implications for the outcome of psychotherapy for anxiety disorders (Zinbarg, Uliaszek, & Adler, 2008), there has been no research to our knowledge evaluating the prognostic (or prescriptive) value of personality traits (e.g., agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness) with respect to the outcome of CBT for SAD (or DCS augmentation). Given findings in the literature linking conscientiousness to health behaviors and greater treatment adherence (Axelsson, Brink, Lundgren, & Lotvall, 2011; Hill & Roberts, 2011), it is plausible that those low in conscientiousness are less able to comply with or utilize treatment. Because it is notable that the advantages for DCS augmentation are much greater in very brief treatments (Guastella, 2008; Hofmann, Meuret, et al., 2006) than in the current 12-session protocol (Hofmann et al., in press), it is possible that patients low in conscientiousness, who may not receive the full dose of CBT, may benefit more from enhancement with DCS. Should it be the case that the DCS augmentation effects are indeed stronger for individuals for whom a standard course of CBT leaves ample room for improvement (see de Kleine et al., 2012), high agreeableness may also emerge as a prognostic and prescriptive variable in our analysis, as it has been associated with suboptimal responding to exposure-based intervention for panic disorder (Harcourt, Kirkby, Daniels, & Montgomery, 1998).

Because extant research on predictors of the efficacy of CBT for SAD and DCS augmentation of CBT, respectively, is limited in scope and has yielded inconsistent findings, we employed an exploratory, hypothesis-generating, rather than hypothesis-driven framework in the present study. Here, we specifically aimed to determine the unique prescriptive and/or prognostic value of each patient characteristic, by evaluating its predictive value while controlling for the influence of other patient characteristics. Acknowledging that multiple tests increase the risk of Type 1 error, we adopted an approach to handling this concern that was developed by Fournier and colleagues (Fournier et al., 2009) and later used by Amir and colleagues (Amir, Taylor, & Donohue, 2011). Specifically, we selected the patient characteristics assessed at the baseline visit and categorized these in meaningful domains (e.g., demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and personality traits). The first step involved a step-wise procedure to identify significant prognostic and prescriptive variables within each domain. The second step involved the simultaneous entry of these prescriptive and prognostic variables identified for each domain in one final model.

Method

Participants

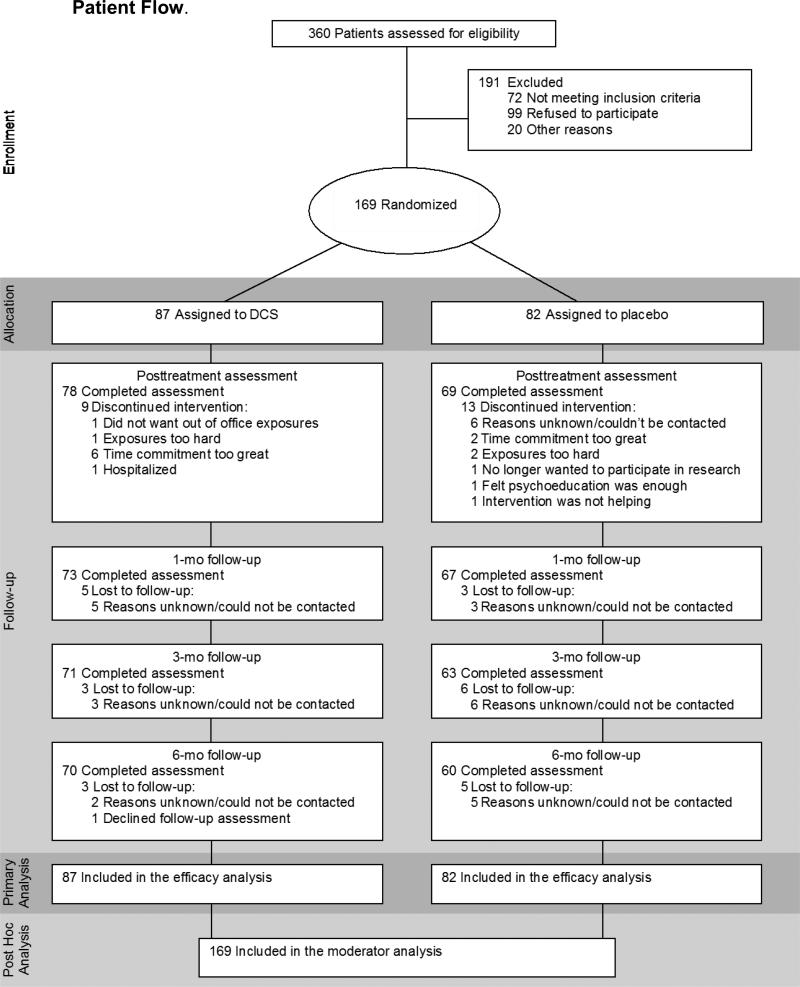

A description of the study design, procedures and main outcome findings have been reported elsewhere (Hofmann et al., in press). The sample consisted of 169 adults diagnosed with generalized SAD as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Diagnosis (SCID-I) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2001) and a score 60 or higher on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz, 1987) at intake. Exclusion criteria were: 1) clinically significant medical disorders; 2) lifetime history of obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, psychosis, or delusional disorders; 3) diagnosis of PTSD, substance abuse or dependence, or eating disorder within the past 6 months; 4) organic brain syndrome, mental retardation, or other cognitive dysfunction; 5) clinically significant suicidal ideation or behavior within the past 6 months; 6) concurrent psychotropic medication; 7) concurrent psychotherapy; 8) prior non-response to exposure therapy; and 9) women who were pregnant, lactating, or of childbearing potential who were not using medically accepted forms of contraception. Figure 1 depicts the participant flow.

Figure 1.

Patient Flow.

Study Design and Treatments

Eligible participants were enrolled at three study sites: Boston University (BU), Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and Southern Methodist University (SMU). Participants at each site participated in an identical 12-session CBT protocol and were randomly assigned to treatment condition at session 3 using a computer-generated allocation schedule that stratified by baseline SAD severity (i.e., LSAS score ≤70 or >70; Liebowitz et al., 1992). Patients were randomized in a double-blind fashion and received 50 mg of DCS (N=87) or an identical looking placebo pill (N=82) at sessions 3-7, one hour prior to each of the 5 sessions.

Primary outcome variables were assessed throughout the treatment phase (at baseline, sessions 2-8, 10, and 12), at posttreatment (week 13), and during a treatment-free follow-up phase (at 1, 3, and 6 months). The present study only reports on data collected during the acute phase (i.e., baseline to posttreatment). The Institutional Review Boards of BU, MGH and SMU approved the study protocol, and patients at each institution provided written informed consent.

CBT

Therapists at each site used a treatment protocol fitting the general timing of Heimberg's cognitive behavioral group therapy (i.e., 12 weekly 2.5-hour sessions; Heimberg & Becker, 2002), but adhering to the exposure targets and strategies described by Hofmann and Otto (Hofmann & Otto, 2008), which was based on the model described by Hofmann (2007). Treatment groups were led by two therapists and comprised 4-6 patients. The first two sessions were devoted to educating patients about the nature and treatment of SAD and introduced cognitive restructuring. In sessions 3-7, patients were led through repeated and prolonged confrontation of feared situations with the purpose of achieving fear extinction. Participants continued exposure practice in sessions 8-12 while utilizing the cognitive restructuring strategies learned in earlier sessions. All therapists were trained and supervised by SGH and JAJS.

Medication

Study capsules were prepared containing: (a) 50mg DCS or (b) pill placebo and administered orally by therapists. In order to maintain the blind, the DCS and placebo capsules were identical in appearance.

Outcome Measure

The LSAS (Liebowitz, 1987), the gold standard 24-item symptom severity measure for SAD, was used as the primary outcome measure in the present study. This scale was administered by independent evaluators blind to treatment condition (Hofmann et al., in press).

Potential Prognostic or Prescriptive Variables

All potential prognostic or prescriptive variables were assessed at baseline, prior to randomization (see Table 1). To facilitate the analyses (see below), we grouped the variables into the following categories:

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Prognostic and Prescriptive Variable Candidates

| Domain | ||

|---|---|---|

|

ETHNICITY/RACE

| ||

| Non-Hispanic White no. (%) | 104 | (61.5%) |

| Hispanic White no. (%) | 18 | (10.7%) |

| Black or African American no. (%) | 16 | (9.5%) |

| Asian no. (%) | 20 | (11.8%) |

| Other no. (%) | 11 | (6.6%) |

|

OTHER DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES | ||

| Male no. (%) | 96 | (56.8%) |

| Age mean (SD) in years | 32.6 | (10.36) |

| Single no. (%) | 113 | (66.9%) |

| Education mean (SD) level | 2.14 | (0.91) |

|

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| MADRS mean (SD) score | 12.53 | (8.69) |

| LSAS mean (SD) score | 81.65 | (81.56) |

| Comorbid diagnoses mean (SD) number | 1.31 | (1.31) |

| CGI-Severity mean (SD) score | 5.29 | (0.84) |

|

PERSONALITY TRAITS | ||

| Neuroticism mean (SD) score | 32.17 | (7.19) |

| Extraversion mean (SD) score | 19.08 | (6.81) |

| Openness mean (SD) score | 30.01 | (6.04) |

| Agreeableness mean (SD) score | 30.10 | (6.22) |

| Conscientiousness mean (SD) score | 27.23 | (8.42) |

Note. MADRS = Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale, LSAS = Liebowitz Social Anxiety Disorder Scale; CGI = Clinical Global Impression. Education level was rated on a 7-point scale (1= Graduate School; 2 = College Graduate; 3 =Partial College; 4 = High School Graduate; 5= Partial High School; 6 = Junior High School; 7 = Less than 7 years of school).

Race/Ethnicity

Given there was meaningful representation (≥10% of the sample (Fournier et al., 2009) of Hispanic, Asian, and African American patients, we compared non-Hispanic White to Hispanic White, African American, Asian and Other (i.e., American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander). We examined this category separately from other demographic characteristics to reduce the number of terms in the initial models.

Other Demographic Characteristics

This domain comprised sex, age, highest education level, and cohabitation status (dichotomized; i.e., single, divorced, widowed or separated vs. married or living with partner). Demographic information was collected using a questionnaire.

Clinical Characteristics

Baseline psychiatric functioning was assessed by clinician-rated measures. This domain comprised clinical severity (as assessed by the Social Phobic Disorders Severity Form; SPD-SC; Liebowitz et al., 1992), depressive symptom severity (as assessed by the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MADRS (Montgomery & Asberg, 1979) and Axis I comorbidity (i.e., number of comorbid Axis I disorders as assessed by the SCID-I; Hofmann et al., 2012).

The SPD-SC is an expansion and adaptation of the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI; Guy, 1976) to SAD. Similar to the original CGI scale, the SPD-SC Form is rated on a 7-point scale to indicate severity. We selected this scale over the original CGI scale because it provides a more detailed analysis of psychological functioning for individuals with SAD. We selected the MADRS because it is designed to measure the overall severity of depressive symptoms and has demonstrated good psychometric properties, specificity for depressive compared to anxiety symptomatology, and sensitivity to change with treatment (Carmody et al., 2006).

Intake clinicians who had received extensive training in the administration and scoring of SCID interviews conducted the SCID. The training involved a series of steps starting with the review of SCID training tapes, followed by the observation of at least six SCID administrations and the administration of at least six SCID interviews with a certified interviewer. SCID interviews were discussed during weekly interviews, during which a senior investigator confirmed diagnoses.

The clinical severity scales (LSAS, SPD-SC, MDRS) were administered by trained independent evaluators blind to treatment condition, who participated in regular cross-site supervision, led by a senior investigator, to prevent interviewer drift and assure high quality of assessment procedures.

Personality Traits

At the baseline session, participants completed the 60-item NEO-Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992), which is a psychometrically-sound measure of the five traits from the Five-Factor model of personality: agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness.

Data Analysis

We followed the approach to identifying prognostic and prescriptive variables developed by Fournier and colleagues (Fournier et al., 2009) and later used by Amir and colleagues (Amir et al., 2011). Specifically, we analyzed LSAS scores collected from baseline to posttreatment using multilevel models (MLMs). Using all obtained data from all participants, MLM is an intent-to-treat approach that estimates both a growth curve (i.e., slope of change) and intercept for each individual. We used maximum likelihood estimation and an unstructured covariance matrix for the errors of the repeated measures (all simplifications of the covariance matrix resulted in significantly higher deviance statistics for the models). Degrees of freedom (dfs) for the significance tests for the regression coefficients were calculated using the Satterthwaite approximation, which yields different dfs for each coefficient. Analyses were completed using the mixed effects models in SPSS 19.0. Primary outcome findings for the trial are described elsewhere (Hofmann et al., in press). In this previous report, the growth curve for LSAS was found to be linear during acute treatment, so it was modeled as linear here. Since we centered the Time variable at posttreatment, the intercept and main effects in the model reflect scores at posttreatment (not at baseline). Hence, level 1 of the multilevel model (which describes the growth curve within individuals over time) was comprised of the intercept (at posttreatment) and linear Time. Level 2 was comprised of individual characteristics that predicted the intercept (posttreatment score) and/or the slope of improvement over time. The level 2 variables were our potential prognostic/prescriptive variables and treatment condition, and the interaction of the prognostic/prescriptive variables with treatment condition. Continuous predictors were converted to z-scores to facilitate comparison among them (and to center them at their means for the interactions), and dichotomous predictors were coded −.5, +.5.

As described above, a prognostic variable has a significant relation with outcome irrespective of study condition (DCS-augmented CBT vs. placebo-augmented CBT), and therefore requires evidence of a significant effect both on the slope (a prognostic variable x Time interaction) and the intercept (Fournier et al., 2009). A prescriptive variable, on the other hand, predicts either the direction and/or magnitude of the differential rates of improvement between DCS-augmented and placebo-augmented CBT. As such, a prescriptive variable requires evidence of a significant interaction effect both on the slope (a prescriptive variable x Condition x Time interaction) and intercept (Fournier et al., 2009). Accordingly, all analyses included the following predictors: Condition, Time, and Condition x Time. For all prognostic/prescriptive variables, we added their main effect and their interactions with Condition, Time, and Condition x Time as additional predictors of outcome. Finally, because Initial Severity (as indexed by Social Phobic Disorders Severity Form; Liebowitz, 1992) has been associated with treatment outcome in this data set (Hofmann et al., in press) and since Sex has been associated with treatment condition in this dataset (Hofmann et al., in press), we included Initial Severity, Initial Severity x Time, and Sex as control variables in every analysis.

Following Fournier et al. (Fournier et al., 2009) and Amir et al. (Amir et al., 2011), we first conducted a step-wise procedure for each domain of predictors (race/ethnicity, other demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, personality traits), separately. In Step 1, we tested a model including all variables for a given domain (as well as their interactions with Condition, Time, and Condition x Time). Step 2 retained the terms from Step 1 that were significant at p<.20. Step 3 retained the terms from Step 2 that were significant at p<.10. Finally, Step 4 retained the terms from Step 3 that were significant at p<.05. In all these steps, lower level main effects and interactions of a higher level interaction were retained if the higher order interaction was retained, regardless of their significance (i.e., a main effect was retained if its interaction with any other variable was retained, regardless of the significance of the main effect). Finally, each term that was significant at p<.05 in Step 4 (within each domain) was included in a final model (across domains), allowing the testing of the effects of each variable while controlling for the effects of other variables.

Results

Step-Wise Analyses within each Domain

The results of the step-wise procedure for each domain are presented in Table 2. In the text, we report only the significant results of Step 4 for each domain. We discuss the form and interpretation of each significant finding in the last section of the Results, under Final Model.1

Table 2.

Step-Wise Analyses

| Change over Time | Posttreatment Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain/Predictor | b (SE) a | p | b (SE) b | p |

|

DOMAIN: ETHNICITY/RACE

| ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Hispanic | .06 (.52) | −5.21 (5.25) | ||

| Black or African American | −1.38 (.54) | * | −13.31 (5.41) | * |

| Asian | .06 (.50) | 1.53 (5.04) | ||

| Other | −.75 (.69) | −3.77 (6.92) | ||

| Hispanic × Condition | .41 (1.04) | 4.88 (10.46) | ||

| Black or African American × Condition | .23 (1.07) | 9.21 (10.69) | ||

| Asian × Condition | 1.34 (1.00) | †† | 10.34 (10.06) | |

| Other × Condition | 1.43 (1.37) | 23.36 (13.73) | † | |

|

Step 2 (retain effects at p<.20)c | ||||

| Black or African American | −1.33 (.52) | * | −13.95 (5.28) | ** |

| Asian | .07 (.50) | 1.53 (5.02) | ||

| Other | 1.40 (3.25) | |||

| Asian × Condition | 1.22 (.98) | 9.76 (9.96) | ||

| Other × Condition | 8.12 (6.42) | |||

|

Step 3 (retain effects at p<.10)c | ||||

| Black or African American | −1.30 (.52) | * | −13.79 (5.23) | ** |

|

Step 4 (retain effects at p<.05)c | ||||

| Black or African American | −1.30 (.52) | * | −13.79 (5.23) | ** |

|

DOMAIN: OTHER DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | .13 (.17) | .99 (1.73) | ||

| Education | .04 (.16) | −.19 (1.62) | ||

| Single | −.95 (.36) | ** | −9.48 (3.65) | ** |

| Age × Condition | −.56 (.34) | † | −3.73 (3.42) | |

| Education × Condition | .37 (.32) | 1.10 (3.20) | ||

| Single × Condition | .62 (.72) | 9.11 (7.27) | ||

|

Step 2 (retain effects at p<.20)c | ||||

| Age | .12 (.16) | −.69 (1.67) | ||

| Single | −.99 (.35) | ** | −10.04 (3.54) | ** |

| Age × Condition | −.36 (.30) | −2.01 (3.07) | ||

|

Step 3 (retain effects at p<.10)c | ||||

| Single | −.84 (.32) | ** | −9.19 (3.25) | ** |

|

Step 4 (retain effects at p<.05)c | ||||

| Single | −.84 (.32) | ** | −9.19 (3.25) | ** |

|

DOMAIN: CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Baseline MADRS | −.07 (.16) | 1.58 (1.63) | ||

| Number of Comorbid Diagnoses | −.03 (.16) | .63 (1.65) | ||

| Baseline MADRS × Condition | .35 (.32) | 2.34 (3.27) | ||

| Number of Comorbid Diagnoses × Condition | .33 (.32) | .55 (3.30) | ||

|

(Steps 2-4 were not completed for this domain given that there were no significant effects in Step 1) | ||||

|

DOMAIN: PERSONALITY TRAITS | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | .004 (.18) | 3.12 (1.83) | † | |

| Extraversion | −.17 (.17) | −.49 (1.74) | ||

| Openness | .21 (.15) | †† | .39 (1.57) | |

| Agreeableness | .13 (.16) | 2.21 (1.61) | †† | |

| Conscientiousness | −.04 (.17) | −1.37 (1.76) | ||

| Neuroticism × Condition | .48 (.35) | †† | .52 (3.63) | |

| Extraversion × Condition | −.10 (.34) | −3.03 (3.47) | ||

| Openness × Condition | .15 (.31) | 1.45 (3.17) | ||

| Agreeableness × Condition | .71 (.31) | * | 4.92 (3.22) | †† |

| Conscientiousness × Condition | −.66 (.34) | † | −4.73 (3.53) | †† |

|

Step 2 (retain effects at p<.20)c | ||||

| Neuroticism | .05 (.17) | 3.08 (1.78) | † | |

| Openness | .19 (.15) | .43 (1.55) | ||

| Agreeableness | .12 (.16) | 2.04 (1.60) | ||

| Conscientiousness | −.07 (.17) | −1.47 (1.72) | ||

| Neuroticism × Condition | .48 (.34) | †† | 1.46 (3.49) | |

| Agreeableness × Condition | .69 (.31) | * | 4.96 (3.18) | †† |

| Conscientiousness × Condition | −.69 (.34) | * | −5.47 (3.44) | †† |

|

Step 3 (retain effects at p<.10)c | ||||

| Neuroticism | 2.46 (.85) | ** | ||

| Agreeableness | .16 (.16) | 2.18 (1.58) | †† | |

| Conscientiousness | −.09 (.15) | −1.65 (1.59) | ||

| Agreeableness × Condition | .69 (.31) | * | 5.07 (3.17) | †† |

| Conscientiousness × Condition | −.85 (.30) | ** | −5.98 (3.07) | † |

|

Step 4 (retain effects at p<.05)c | ||||

| Neuroticism | 2.46 (.85) | ** | ||

| Agreeableness | .16 (.16) | 2.18 (1.58) | †† | |

| Conscientiousness | −.09 (.15) | −1.65 (1.59) | ||

| Agreeableness × Condition | .69 (.31) | * | 5.07 (3.17) | †† |

| Conscientiousness × Condition | −.85 (.30) | ** | ×5.98 (3.07) | † |

|

FINAL MODEL | ||||

| Black or African American | −1.50 (.51) | ** | −16.45 (5.10) | ** |

| Single | −.88 (.31) | ** | −9.30 (3.17) | ** |

| Initial Severity | −.82 (.15) | ** | 4.54 (1.48) | ** |

| Neuroticism | 2.39 (.85) | ** | ||

| Agreeableness | .11 (.15) | 1.69 (1.52) | ||

| Conscientiousness | .01 (.15) | −.69 (1.54) | ||

| Agreeableness × Condition | .67 (.30) | * | 4.84 (3.04)1 | †† |

| Conscientiousness × Condition | −.84 (.29) | ** | −5.82 (2.93) | * |

Values represent unstandardized beta coefficients predicting the slope of change in Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale scores over assessment occasions. Thus, these coefficients represent the interaction of the predictor (in the left hand column) with Time. Negative values indicate greater change during treatment. For interaction terms, values represent the difference between DCS and placebo with respect of the magnitude of the effect.

Values represent unstandardized beta coefficients predicting Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale scores at week 13 (posttreatment). Thus, negative values indicate lower estimates posttreatment scores. For interaction terms, values represent the difference between DCS and placebo with respect of the magnitude of the effect.

Nonsignificant main effects were retained in subsequent steps if their interactions with Time or Condition were significant.

P < .20

P < .10

p < .05

p < .01

Race/Ethnicity

In Step 4 for the race/ethnicity domain, African American ethnicity was a significant predictor of faster linear change in LSAS scores (African American ethnicity x Time interaction: b=−1.30 [SE=.52], t[151]=− 2.51, p=.013). As a consequence, African American patients had lower posttreatment LSAS scores than patients who were not African American (b=−13.79 [SE=5.23], t[150]=−2.64, p=.009). No other race/ethnicity prognostic or prescriptive variables were identified.

Other Demographic Characteristics

In Step 4 of this domain, cohabitation status was a significant predictor of both faster linear change in LSAS (Cohabitation Status x Time interaction: b=−.84 [SE=.32], t[148]=−2.60, p=.010) and lower posttreatment LSAS scores (b=−9.19 [SE=3.25], t[147]=−2.83, p=.005). No other demographic prognostic or prescriptive variables were identified.

Clinical Characteristics

Neither depressive symptom severity nor the number of comorbid Axis I comorbid disorders (whether log transformed to reduce skewness or not) were related to the slope of improvement in LSAS or posttreatment LSAS scores. It should be noted that initial severity on the on the SPD-SC was included in all analyses. Its relation to LSAS is reported under the Final Model below.

Personality Traits

In Step 4 for the personality traits domain, agreeableness was a moderator of the treatment effects on slope of LSAS over time (Agreeableness x Condition X Time interaction: b=.69 [SE=.31], t[154]=2.21, p=.029), but not on posttreatment LSAS scores (see Table 2). In this Step 4, conscientiousness also interacted with treatment condition to predict the slope of change in LSAS (Conscientiousness x Condition x Time interaction: b=−.85 [SE=.30], t[149]=−2.83, p=.005), and was marginally associated with the effect of treatment Condition on posttreatment LSAS scores (Conscientiousness x Condition interaction: b=−5.98 [SE=3.97], t[147]=−1.95, p=.053). Lastly, Neuroticism was associated with posttreatment LSAS scores (but not as a moderator) in Step 4, suggesting that Neuroticism was positively associated with posttreatment LSAS scores irrespective of condition or time (see Table 2).

Final Model with All Significant Prognostic and Prescriptive Variables

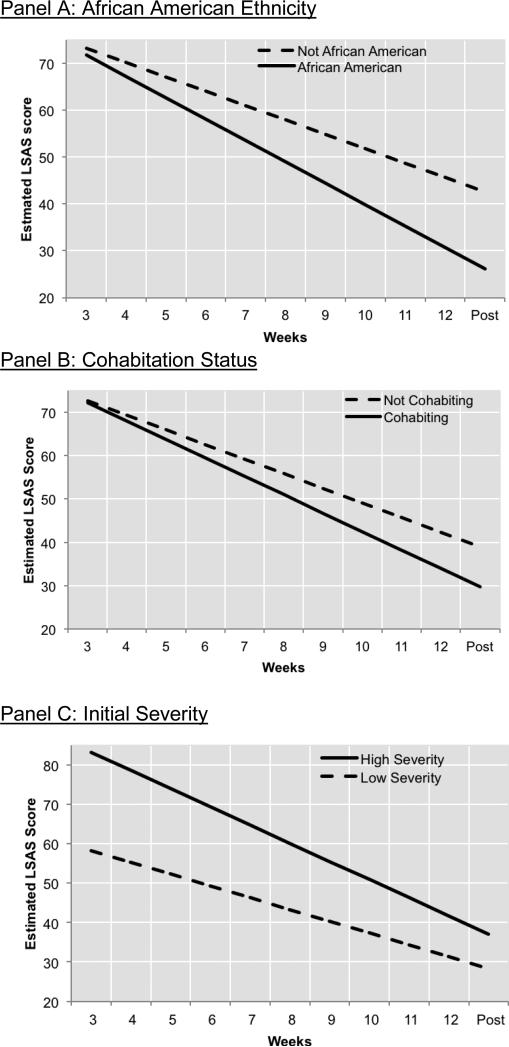

The final model included the simultaneous entry of the prescriptive and prognostic variables found to be significant in Step 4 of the previous sets of analyses (and again included the Initial Severity, Initial Severity x Time, and Sex). The results are presented in Table 2 and Figures 2 and 3. All prescriptive and prognostic variables that were significant in the step-wise analyses for each domain (see Table 2) retained significance in the final model. Specifically, African American patients evidenced greater rates of improvement during CBT (African American Ethnicity x Time interaction: b=−1.50 [SE=.51], t[152]=−2.95, p=.004), and lower posttreatment LSAS scores (b=−16.44 [SE=5.10], t[152]=−3.23, p=.002) than patients who were not African American. Compared to patients who are not African American, African American patients showed a 49% faster rate of improvement in LSAS scores during treatment (see Figure 2a). Similarly, cohabitation status remained associated with faster linear change in LSAS (Cohabitation x Time interaction: b=.88 [SE=.31], t[149]=2.81, p=.006) and lower posttreatment LSAS scores (b=−9.30 [SE=3.17], t[149]=2.93, p=.004; see Figure 2b). Those cohabitating showed a 29% faster rate of improvement in LSAS over time compared to those who were not cohabitating. In these analyses, greater initial severity also remained a significant predictor of faster linear change in LSAS (Initial Severity x Time interaction: b=−82 [SE=.15], t[149]=−5.63, p<.001), but also of higher posttreatment LSAS scores (b=4.54 [SE=1.48], t[15]=−3.06, p=.003; see Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Prognostic variables.

African American patients showed a greater response to CBT than patients who were not African American (panel A), individuals cohabitating showed greater response to CBT than those who were not cohabitating (panel B), and patients presenting with greater initial severity showed greater response to CBT than those who were lower in initial severity (panel C). Note: High Severity was operationalized as 1 SD above the mean, and Low Severity was 1 SD below the mean.

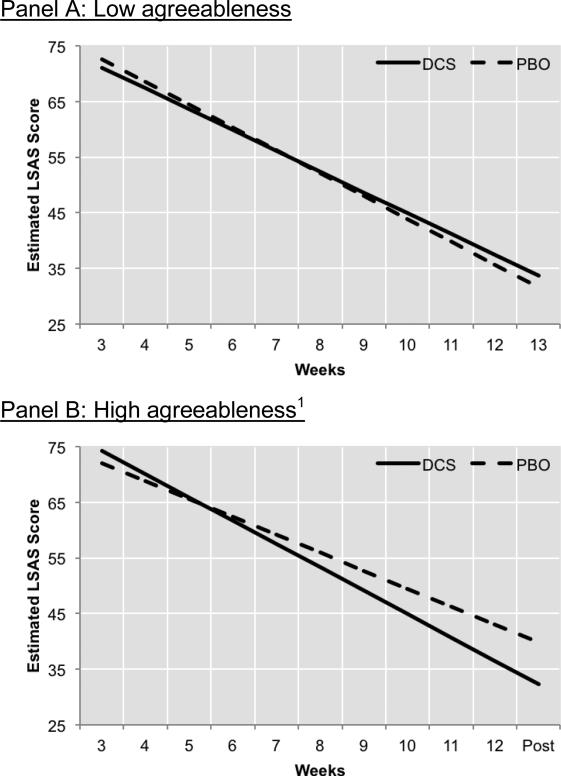

Figure 3. Prescriptive variable: Agreeableness.

There was no difference in treatment response between DCS- and placebo-augmented CBT among patients who scored low in agreeableness (panel A). However, there was a significant difference between these groups among patients who scored high on agreeableness (panel B). Note: High Agreeableness was operationalized as 1 SD above the mean, and Low Agreeableness was 1 SD below the mean.

In this final model, agreeableness remained a moderator of the effect of DCS on slope of improvement in LSAS over time (Agreeableness x Condition x Time interaction: b=.67 [SE=.30], t[153]=2.21, p=.029). Decomposing this three-way interaction showed that Treatment Condition only impacted the slope of improvement in LSAS over time among patients high in agreeableness (those who scored 1 SD above the Agreeableness mean; Condition x Time interaction: b=.97 [SE=.43], t[147]=2.27, p=.025; see Figure 3b), but not for patients who were low in agreeableness (those scoring 1 SD below the Agreeableness mean; Condition x Time interaction: b=−.37 [SE=.41], t[157]=−.90, p=.372; see Figure 3a). Among patients high in agreeableness, those receiving DCS-augmented CBT evidenced a 35% faster rate of improvement in LSAS scores during treatment relative to those receiving placebo-augmented CBT. The agreeableness moderator effect was not significant for posttreatment LSAS scores (see Table 2).2

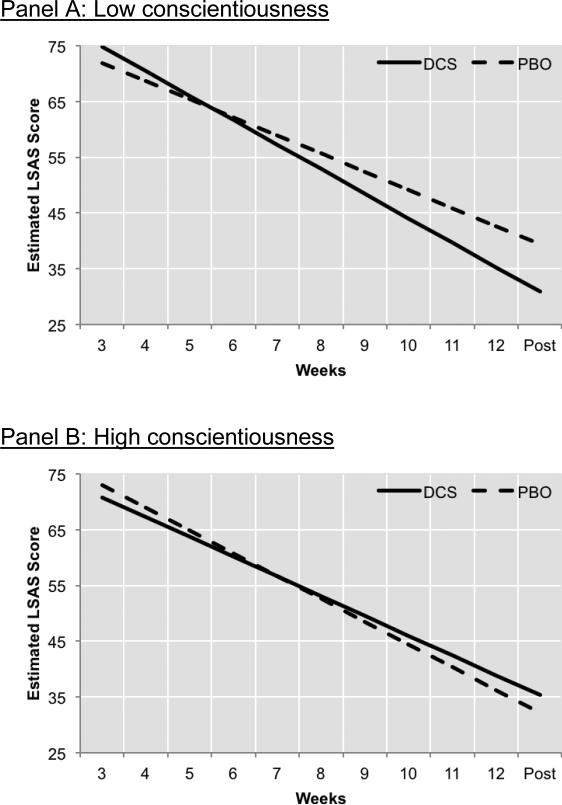

Conscientiousness also remained a significant prescriptive indicator as it interacted with treatment to predict the change in LSAS over time (Conscientiousness x Condition x Time interaction: b=−.84 [SE=.29], t[148]=−2.90, p=.004) as well as LSAS at posttreatment (b=−5.82 [SE=2.94], t[147]=−1.99, p=.049). Follow-up analyses indicated that the advantage of DCS- augmented CBT over placebo-augmented CBT was only evident among individuals low in conscientiousness (1 SD below the Conscientiousness mean; Condition x Time interaction: b=1.14 [SE=.42], t[150]=2.73, p=.007; Treatment Condition effect on posttreatment LSAS: b=8.50 [SE=4.22], t[148]=2.02, p=.046; see Figure 4a), but not for patients who were high in conscientiousness (1 SD above the Conscientiousness mean; Condition x Time interaction: b=−.54 [SE=.40], t[149]=−1.35, p=.178; Treatment Condition effect on posttreatment LSAS: b=−3.15 [SE=4.07], t[151]=-0.77, p=.44; see Figure 4b). Among patients low in conscientiousness, those receiving DCS-augmented CBT evidenced a 32% faster rate of improvement in LSAS scores during treatment as compared to those receiving placebo-augmented treatment.

Figure 4. Prescriptive variables: Conscientiousness.

There was a significant difference in treatment response between DCS- and placebo-augmented CBT among patients who scored low in conscientiousness (panel A). However, there was no significant difference between these groups among patients who scored high on conscientiousness (panel B). Note: High Conscientiousness was operationalized as 1 SD above the mean, and Low Conscientiousness was 1 SD below the mean.

The only other significant effect in the final model was a main effect for Neuroticism, b=2.39 (SE=.85), t(155)=2.81, p=.006, suggesting that patients who were higher in Neuroticism had higher LSAS scores at posttreatment and throughout treatment.

Given the extant work relating conscientiousness to treatment adherence (Axelsson et al., 2011; Hill & Roberts, 2011), we investigated whether the effects of conscientiousness may have been due to its relation with session attendance or homework compliance as measured by therapists. We found no relation between conscientiousness and number of treatment sessions attended or homework compliance (rs<.08, ps>.29).

Discussion

The present study aimed to identify baseline characteristics associated with differential response to DCS augmentation of CBT and response to CBT for SAD overall. Using a multivariate approach, African American ethnicity and cohabitation status emerged as positive prognostic variables of CBT outcome. In addition, initial severity was associated with a faster rate of symptom improvement, but remained related to higher symptom severity at posttreatment. Lastly, both agreeableness and conscientiousness emerged as prescriptive variables, such that the positive augmentation effects of DCS (over placebo) were only evident among persons high in agreeableness or low in conscientiousness, respectively.

The findings of the present study extend previous research in a number of meaningful ways. First, our results suggest that patients presenting with severe generalized SAD, as defined by the presence of high symptom severity, do not respond more poorly to CBT emphasizing exposure to feared cues coupled with cognitive restructuring (Hofmann, 2007; Hofmann & Otto, 2008) relative to patients with less severe SAD. Instead, our findings suggest that patients who present with high symptom severity actually improve faster and may simply need longer treatment to achieve equivalence with those presenting with low(er) initial severity (Smits, Minhajuddin, Thase, & Jarett, 2012). It is important to note here that our analyses indicate SAD symptom severity as a prognostic variable over Axis I comorbidity and depressive symptom severity. Also, our results do not indicate a role for DCS in speeding the rate of improvement for patients high in initial severity as has been hypothesized (Otto et al., 2010) and observed in a recent smaller-scale trial involving patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (de Kleine et al., 2012).

Second, the results of the present study provide much needed information on how ethnic minorities fare with CBT relative to their non-Hispanic White counterparts (Horrell, 2008). Indeed, research in this area is sparse, particularly as it relates to SAD, and initial results of studies of CBT for other disorders have provided mixed results (Horrell, 2008). For example, Markowitz and colleagues (Markowitz, Spielman, Sullivan, & Fishman, 2000) found African American ethnicity predicted poorer response to CBT for depression in HIV positive men, while Miranda and colleagues (Miranda et al., 2003) noted no differences among African American, Latina and White women regarding the effects of CBT on depressive symptoms. In contrast, our findings indicate that African Americans respond better to CBT for SAD than patients who are not African American. In fact, it was notable that average posttreatment score for African Americans was in the remission range. Accordingly, our findings may lessen concerns about whether empirically supported treatments, such as CBT for SAD, are effective for diverse populations (Hall, 2001). Given the novelty of this result in relation to existing findings, it seems premature to speculate on the underlying causes of this finding. However, if our results are replicated, understanding why African Americans may respond better to CBT for SAD than their non-African American counterparts should be a focus of future work.

Third, controlling for other demographic, clinical severity, and personality variables, cohabitation status was a significant predictor of CBT outcome in our analysis, with cohabitating participants evidencing greater symptom improvement and lower posttreatment severity. It has been suggested that persons who cohabitate may do particularly well with CBT because, compared to those who do not cohabitate, they tend to have a greater social network and because they have more opportunities to practice with their partners or friends the tools they have learned (Fournier et al., 2009). This may be particularly relevant to CBT for SAD, which stresses repeated exposure to social interaction and performance situation outside the session (Heimberg & Becker, 2002; Hofmann & Otto, 2008). Alternatively, relative to individuals who are single, those who cohabitate may receive greater social support, which may confer additional therapeutic effects.

Fourth, our analyses identified agreeableness and conscientiousness as (independent) moderators of the efficacy of DCS for augmenting CBT of SAD. Only individuals low in conscientiousness or high in agreeableness, respectively, achieved greater benefit from DCS as compared to placebo augmentation. To our knowledge, this is the first indication of a potential matching strategy (i.e., personality traits) for DCS augmentation of CBT, since no moderators emerged in a recent meta-analysis of small-scale efficacy trials of DCS (Bontempo et al., 2012). In contrast to our hypothesis, follow-up analyses provided no evidence suggesting that individuals low in conscientiousness received less treatment or utilized treatment less well on the measures available (e.g., session attendance, homework compliance). Nonetheless, there is evidence, albeit mixed, of potential different central nervous system characteristics between those low and high in conscientiousness, which may suggest there may be a specifically biological explanation for the observed effects. Specifically, Hiio and colleagues (Hiio et al., 2011) reported that low conscientiousness is a characteristic of carriers of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met genotype Met-allele and several studies have shown that the BDNFMet allele has been associated with an impairment in extinction learning in both mice (Soliman et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2009) and humans (Soliman et al., 2010), likely because of reduced ventromedial prefrontal activity and increased amygdala activity during extinction. Importantly, Yu and colleagues documented that this extinction learning deficit exhibited by BDNFmet mice can be reversed by the administration of DCS (Yu et al., 2009).

We are not aware of any research that may provide a possible biological explanation for the moderator effects of agreeableness. However, previous research has associated high agreeableness with suboptimal responding to exposure-based interventions (Harcourt et al., 1998), thus potentially pointing to high agreeableness as a marker for extinction learning deficits. Therefore, our findings may be consistent with the hypothesis that DCS augmentation is only indicated for patients who are in some way compromised with respect to learning with extinction-based therapy. Together, these observations call for studies examining the relation among fear extinction-relevant biological processes/factors (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphisms) and behavioral factors, conscientiousness, agreeableness (or personality traits more broadly) and the efficacy of DCS augmentation of CBT.

Although this research has produced a number of potentially useful findings, and has done so while controlling for a wide range of possible third variables, a number of limitations deserve mention. First, following Fournier and colleagues (2009) and Amir and colleagues (2011), we adopted an exploratory approach to identifying prognostic and prescriptive variables. Here, we were limited by examining only individual characteristics that had been assessed at baseline in a study involving adults with generalized SAD who were randomly assigned to receive 12 sessions of group CBT either with 50mg of DCS or placebo during sessions 3-7. Accordingly, our findings may not generalize to CBT protocols of a different duration or individual modality, DCS augmentation of a different dose or frequency, or a non-generalized SAD sample. Moreover, given we only had data available on a limited set of individual characteristics, there are plausible third-variable explanations (e.g., genetic factors) that may be relevant. Second, as is typical in efficacy trials, we employed a number of exclusion criteria and therefore may have inadvertently restricted the generalizability of the findings to a medication-free SAD sample without severe psychiatric or physical health comorbidity. Thus, it is possible that the predictive value of clinical characteristics would have been different in this study had we included patients who were taking psychotropic medications and/or presented with more severe comorbid psychopathology. Third, because the comparator condition was placebo-augmented CBT, we cannot determine whether the prognostic factors observed in the present study are specific to CBT for SAD that is combined with placebo or whether these also generalize to CBT without placebo augmentation. Fourth, because we already conducted a large number of tests, we did not examine interactions among predictor variables. As such, we cannot rule out the possibility that the prognostic or prescriptive effects observed in the present study vary as a function of other predictor variables. Examining such more nuanced relations is an important direction for future research (Fournier et al., 2009). Lastly, because we limited the analyses to symptom changes during the course of treatment, the identified prognostic and prescriptive variables may be specific to short-term effects and may not generalize to long-term effects.

Despite these limitations, this study is the first to provide information on patient characteristics that are associated with response to DCS-augmented CBT for SAD. Clinically, these data, if replicated, can offer guidance as practitioners make decisions about treatment strategies with this patient population. With respect to theory and future research, the observed relations in the present study may be useful for enhancing the understanding of the mechanisms of CBT for anxiety disorders and thereby ultimately aid in the development of more potent, personalized, interventions for these disabling conditions.

Acknowledgments

This report was supported by grants R01MH075889 (to Mark Pollack, M.D.) and R01MH078308 (to Stefan Hofmann, Ph.D.) from the National Institute of Mental Health. We appreciate the support of the NIMH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Dr. Smits receives royalties from various book publishers for work unrelated to this study. Dr. Hofmann has served as a consultant for Merck and Schering-Plough and receives book royalties from various book publishers for work unrelated to this study. Dr. Costa receives royalties from the NEO-FFI. Dr. Simon reported unrelated financial affiliations for past 36 months as: research support from American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Forest Laboratories, National Institute of Health and Department of Defense. She also receives honoraria for speaking for the MGH Psychiatry Academy and spousal equity in Elan, Dandreon, G Zero, Gatekeeper. Dr. Otto serves as consultant for MicroTransponder, Inc. and receives royalties from various book publishers for work unrelated to this study. Dr. Pollack's disclosures over the last 12 months include: Advisory Boards and Consultation: Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Medavante, Merck; Research Grants: NIH Equity: Doyen, Medavante, Mensante Corporation, Mindsite, Targia Pharmaceutical Royalty/patent: SIGH-A, SAFER interviews. Dr. Rosenfield, Ms. DeBoer, Dr. O'Cleirigh, Dr. Meuret and Dr. Marques report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Per suggestion of a reviewer, we tested whether the results varied as a function of site. We did not observe any significant moderator effects of site.

If one more fully controls initial severity (by also controlling for baseline social anxiety severity as indexed by the Social Phobia Anxiety Inventory; Turner et al., 1989), patients who received DCS also evidence significantly lower posttreatment LSAS scores than those in placebo, b=8.87, t(142)=2.14, p=.034, among patients who score high on agreeableness.

References

- Amir N, Taylor CT, Donohue MC. Predictors of response to an attention modification program in generalized social phobia. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(4):533–541. doi: 10.1037/a0023808. doi: 10.1037/a0023808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KC, Insel TR. The promise of extinction research for the prevention and treatment of anxiety disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):319–321. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.022. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson M, Brink E, Lundgren J, Lotvall J. The influence of personality traits on reported adherence to medication in individuals with chronic disease: an epidemiological study in West Sweden. PLOS One. 2011;6(3):e18241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Heimberg RG, Schneier FR, Fresco DM, Chen H, Turk CL, Liebowitz MR. A placebo-controlled trial of phenelzine, cognitive behavioral group therapy, and their combination for social anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):286–295. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.11. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo A, Panza K, Bloch MH. D-Cycloserine augmentation of behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2012;73(4):533–537. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody TJ, Rush AJ, Bernstein I, Warden D, Brannan S, Burnham D, Trivedi MH. The Montgomery Asberg and the Hamilton ratings of depression: a comparison of measures. European Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16(8):601–611. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.04.008. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Tran GQ, Glass CR. Predictors of response to cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1997;11(3):221–240. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00008-x. doi: Doi 10.1016/S0887-6185(97)00008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Ehlers A, McManus F, Hackmann A, Fennell M, Campbell H, Louis B. Cognitive therapy versus fluoxetine in generalized social phobia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(6):1058–1067. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1058. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collimore KC, Rector NA. Symptom and Cognitive Predictors of Treatment Response in CBT for Social Anxiety Disorder. International Journal of Cognitve Therapy. 2012;5(2):157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Foa EB, Huppert JD, Keefe FJ, Franklin ME, Compton JS, Gadde KM. Fluoxetine, comprehensive cognitive behavioral therapy, and placebo in generalized social phobia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(10):1005–1013. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1005. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Ressler K, Rothbaum BO, Richardson R. Effects of D-cycloserine on extinction: translation from preclinical to clinical work. Journal of the Society of Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.084. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kleine RA, Hendriks GJ, Kusters WJ, Broekman TG, van Minnen A. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of D-cycloserine to enhance exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;71(11):962–968. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.033. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin BA, Heimberg RG, Juster H, Mindlin M. Comorbid anxiety and mood disorders among persons with social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40(1):19–35. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders, Clinician Version. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; Arlington, VA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, Gallop R. Prediction of response to medication and cognitive therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(4):775–787. doi: 10.1037/a0015401. doi: 10.1037/a0015401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastella AJ, Richardson R, Lovibond PF, Rapee RM, Gaston JE, Mitchell P, Dadds MR. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of D-cycloserine on enhancement of exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. In: Klein D, Gorman J, Fyer A, Liebowitz M, editors. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry. Karger Publishing; Basel, Switzerland: 1987. pp. 141–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN. Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities: Empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(3):502–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt L, Kirkby K, Daniels B, Montgomery I. The differential effect of personality on computer-based treatment of agoraphobia. Comprensive Psychiatry. 1998;39(5):303–307. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Becker RE. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia: Basic mechanisms and clinical strategies. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, Holt CS, Welkowitz LA, Klein DF. Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12-week outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(12):1133–1141. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiio K, Merenakk L, Nordquist N, Parik J, Oreland L, Veidebaum T, Harro J. Effects of serotonin transporter promoter and BDNF Val66Met genotype on personality traits in a population representative sample of adolescents. Psychiatric Genetics. 2011;21(5):261–264. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32834371e8. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32834371e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL, Roberts BW. The role of adherence in the relationship between conscientiousness and perceived health. Health Psychology. 2011;30(6):797–804. doi: 10.1037/a0023860. doi: 10.1037/a0023860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2007;36:195–209. doi: 10.1080/16506070701421313. doi: 10.1080/16506070701421313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Meuret AE, Smits JA, Simon NM, Pollack MH, Eisenmenger K, Otto MW. Augmentation of exposure therapy with D-cycloserine for social anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(3):298–304. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.298. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Otto MW. Cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder: Evidence-based and disorder-specific treatment techniques. Routledge; London: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Pollack MH, Otto MW. Augmentation treatment of psychotherapy for anxiety disorders with D-cycloserine. CNS Drug Reviews. 2006;12(3-4):208–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00208.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):621–632. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Smits JA, Asnaani A, Gutner CA, Otto MW. Cognitive enhancers for anxiety disorders. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2011;99(2):275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.11.020. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Smits JA, Rosenfield D, Simon NM, Otto MW, Meuret AE, Pollack MH. D-cycloserine as augmentation strategy of cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12070974. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrell SCV. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy with adult ethnic minority clients: A review. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice. 2008;39(2):160–168. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.160. [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Kosfelder J, Schulte D. The impact of comorbidity of depression on the course of anxiety treatments. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29(5):569–591. doi: Doi 10.1007/S10608-005-3340-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledley DR, Huppert JD, Foa EB, Davidson JR, Keefe FJ, Potts NL. Impact of depressive symptoms on the treatment of generalized social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;22(4):161–167. doi: 10.1002/da.20121. doi: 10.1002/da.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. In: Klein D, Gorman J, Fyer A, Liebowitz M, editors. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry. Karger Publishing; Basel, Switzerland: 1987. pp. 141–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR, Schneier F, Campeas R, Hollander E, Hatterer J, Fyer A, Klein DF. Phenelzine vs atenolol in social phobia. A placebo-controlled comparison. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49(4):290–300. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.49.4.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz JC, Spielman LA, Sullivan M, Fishman B. An exploratory study of ethnicity and psychotherapy outcome among HIV-positive patients with depressive symptoms. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research. 2000;9(4):226–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Nathan P, Rapee RM, Campbell BN. Cognitive behavioural group therapy for social phobia: evidence of transportability to community clinics. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012;50(4):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.01.009. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, Krupnick J, Siddique J, Revicki DA, Belin T. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women - A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(1):57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 5):34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Tolin DF, Simon NM, Pearlson GD, Basden S, Meunier SA, Pollack MH. Efficacy of d-cycloserine for enhancing response to cognitive-behavior therapy for panic disorder. Journal of the Society of Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.036. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier FR, Heckelman LR, Garfinkel R, Campeas R, Fallon BA, Gitow A, Liebowitz MR. Functional impairment in social phobia. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1994;55(8):322–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier FR, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Liebowitz MR, Weissman MM. Social phobia. Comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sample. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49(4):282–288. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820040034004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JAJ, Minhajuddin A, Thase ME, Jarrett RJ. Outcomes of acute phase cognitive therapy in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics. 2012;81:153–160. doi: 10.1159/000334909. doi:10.1159/000334909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliman F, Glatt CE, Bath KG, Levita L, Jones RM, Pattwell SS, Casey BJ. A genetic variant BDNF polymorphism alters extinction learning in both mouse and human. Science. 2010;327(5967):863–866. doi: 10.1126/science.1181886. doi: 10.1126/science.1181886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SM, Beidel DC, Wolff PL, Spaulding S, Jacob RG. Clinical features affecting treatment outcome in social phobia. Behaviour Researtch and Therapy. 1996;34(10):795–804. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Wang Y, Pattwell S, Jing D, Liu T, Zhang Y, Chen ZY. Variant BDNF Val66Met polymorphism affects extinction of conditioned aversive memory. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(13):4056–4064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5539-08.2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5539-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinbarg RE, Uliaszek AA, Adler JM. The role of personality in psychotherapy for anxiety and depression. Journal of Personality. 2008;76(6):1649–1687. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00534.x. doi: Doi 10.1111/J.1467-6494.2008.00534.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]