Abstract

A prominent perspective in the gang literature suggests that gang member involvement in drug selling does not necessarily increase violent behavior. In addition it is unclear from previous research whether neighborhood disadvantage strengthens that relationship. We address those issues by testing hypotheses regarding the confluence of neighborhood disadvantage, gang membership, drug selling, and violent behavior. A three-level hierarchical model is estimated from the first five waves of the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, matched with block-group characteristics from the 2000 U.S. Census. Results indicate that (1) gang members who sell drugs are significantly more violent than gang members that don’t sell drugs and drug sellers that don’t belong to gangs; (2) drug sellers that don’t belong to gangs and gang members who don’t sell drugs engage in comparable levels of violence; and (3) an increase in neighborhood disadvantaged intensifies the effect of gang membership on violence, especially among gang members that sell drugs.

Keywords: neighborhood disadvantage, social learning, gang membership, drug selling, violence, conditional effects, fixed-effects, hierarchical modeling

This paper addresses two hypotheses pertaining to the intersection of neighborhood disadvantage, gang membership, drug selling, and violence.1 The first examines whether acquiring the status of gang member coupled with drug selling alters within-individual trajectories of violence. Gang research clearly indicates that joining a gang is a crucial life course transition that facilitates or enhances participation in violence. That growing literature, however, does not isolate gang members who sell drugs from gang members that don’t. Therefore it is unclear whether the well known association between gang membership and violence is driven by the violence of gang members that sell drugs.

The analysis challenges conventional wisdom, which balks at the idea that gang members are more violent when they also occupy the status of drug seller. For instance, Fagan’s (1989) research indicates high variability among gangs in the extent to which they commit serious delinquency and are involved in drug trafficking. He concludes that “Serious crime and violence occur regardless of the prevalence of drug dealing within the gang” and that “involvement in use and sales of the most serious substances does not necessarily increase the frequency or severity of violent behavior” (p. 660). And in their authoritative review of the gangs, drugs, and violence connection, Howell and Decker (1999: p. 8) definitively state that “Youth gang members actively engage in drug use, drug trafficking, and violent crime,” but “gang member involvement in drug sales does not necessarily result in more frequent violent offenses.”

The second hypothesis examines whether the relations referenced in the first hypothesis increase in magnitude as neighborhood disadvantage increases. 2 Previous quantitative research examining the relationship between neighborhood context, gang membership, and delinquency contradicts this hypothesis (see below). Yet, the neighborhood effect hypothesis persists because of its centrality to structural theories of crime such as Akers’ (1998) social structure and social learning formulation, its consistency with some qualitative research on gangs and the nature of street drug trafficking, and because research that addresses this important topic remains rare.

We move beyond prior research with hierarchical analysis of the first five waves of the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY97). The NLSY97 is a representative sample of adolescents who were between twelve and sixteen years of age in 1997. Overcoming a weakness in prior research the national sampling strategy produced substantial variation in neighborhood context – an often overlooked but critical consideration when studying neighborhood effects. In addition, most gang research, whether quantitative or qualitative, relies on between-individual (i.e., cross-sectional) analysis. However, within-individual analyses with group mean centering are better suited to the questions we pose because they permit assessment of changes in violence that occur when one joins a gang and/or begins selling drugs, and because they offer a conservative safeguard against selection effects.

Reflecting the interstitial character of gang membership that is well documented in prior research, the gang members in our data typically enter a gang in one year and exit the next, although a small number remain across several waves. Interstitial participation in gangs is an essential feature of the data that permits analysis of within individual change as respondents enter and exit gang membership and move into and out of drug selling while residing in a wide variety of neighborhood contexts. The longitudinal design coupled with substantial neighborhood-level variation makes the NLSY97 a strong candidate to investigate these questions. In the sections that follow research, theory, and hypotheses are reviewed.

BACKGROUND

RESEARCH

Gang research indicates that gang members are more likely to be violent than non members. Thrasher (1927) was among the first to document that gangs are inherently conflict groups, that members fight to preserve what is theirs, and that much fighting is status oriented involving members of the same gang more so than competing gangs. Those findings have been replicated by qualitative research in different time periods and across several cities (Spergal 1964; Short and Strodtbeck 1965; Klein 1971; Hagedorn 1988; Decker and Van Winkle 1996). Quantitative data also support the conclusion that gang members engage in more violence than non-members (Battin et al. 1998; Esbensen and Huizinga 1993; Thornberry et al. 1993, 2003).

Previous research indicates that gang members spend a large portion of time hanging out with other gang members (Decker and Van Winkle 1996). It is in this context that members receive continuous social reinforcement of norms supporting gang and drug involvement. Gang activity and drug selling are embedded in and facilitated by a subculture comprised of individuals whose attitudes and beliefs are antithetical to mainstream, conventional society, and violence among gang members reflects in part adherence to behavioral norms that support violence as a means of conflict resolution (Anderson 1999). Status and respect are attained by demonstrating courage and by being ready and willing to employ violence when it is perceived to be necessary to protect oneself, peers, or the neighborhood from internal or external threats. Literature also indicates a heightened risk of violent victimization among drug sellers. Street-level drug selling is a cash business (without legal recourse) and this increases the likelihood that transactions will evolve into rip-offs and other violent altercations, what some have termed “systemic violence” (Goldstein 1985, 1989).3 Sellers therefore develop methods for reducing that risk including adopting a tough street image and using or threatening the use of retaliatory violence (Jacobs 2000; Jacobs and Wright 2006).

There is some quantitative research that suggests the neighborhood context in which gang membership and drug selling take place increases the frequency of violence. Fagan (1989: p. 662) articulates this potential well, noting that “one plausible explanation for variation in gang violence may lie in the relative social and economic isolation of their milieu … violence within gangs may reflect both the marginalization of gang members and the marginalization of the neighborhood itself.” Research indicates that drug sellers in highly distressed contexts perceive few legitimate alternatives, which in some cases increases commitment to selling (Bourgois 1995). Also consistent with our approach a handful of neighborhood-level studies have shown that the emergence of gangs is associated with neighborhood disadvantage and with heightened violence (Rosenfeld, Bray, and Eglen 1999; Tita and Ridgeway 2007). Yet those studies treat neighborhoods and the gangs in them – rather than gang members -- as units of analysis and therefore don’t address the nexus of gang membership, drug selling, and violence nor the cross-level prediction that the relationship is stronger as disadvantage becomes more severe.

The analysis that is closest to the one presented below examines the interaction of gang membership and neighborhood disadvantage on delinquency, violence, and drug selling although it does not make the distinction between gang members who do and don’t sell drugs (Hall et. al. 2005). They found that gang membership increases general delinquency and violence, but the balance of evidence indicated no support for an interaction effect. Other differences in methods distinguish that analysis from the research presented below. First, the disadvantage scale includes a variety of non-standard indicators which likely obscure its meaning and interpretation. For instance, racial and ethnic heterogeneity is included whereas in social disorganization research it is treated as a theoretically distinct construct. Second, four waves of data are analyzed independently rather than the more efficient and conservative strategy of pooling waves and estimating within-individual fixed effects (Johnston and DiNardo 1997). Finally, and perhaps most importantly for evaluating cross-level interactions, the data used in that analysis were collected in just one city (Rochester, NY) and thus there is far less variability in residential context than is the case with a data collection carried out on a national scale such as the NLSY97.

THEORETICAL MODEL

Differential association and social learning processes are well-established predictors of adolescent delinquency and violent behavior at the micro level (Akers 1998; Matsueda 1982; 1988; Warr and Stafford 1991). Differential association (DA) theory focuses on the cognitive processes that give rise to criminal attitudes (Sutherland 1939). To understand why someone engages in violence, it is suggested, one must understand why that person views a situation as an occasion for violent behavior. Individuals learn attitudes, rationalizations, techniques, and motives that define the meaning of violence, definitions that are either favorable or unfavorable, in the context of interaction within intimate primary groups, such as in gang and drug subcultures.4 Definitions of violence to which an individual is exposed early in life (priority), from a person who is admired or looked up to (intensity), for longer durations, and with greater frequency have greater weight. Internalized violent attitudes, rationalizations, and motives eventually lend themselves to violent acts, particularly when the individual continues to be exposed to favorable, as opposed to unfavorable, definitions of violence (Akers, Krohn, Lanza-Kaduce, and Radosevich 1979).

Social learning theory draws from the psychological principle of operant conditioning and extends DA theory by providing a more complete explanation of the mechanisms by which individuals acquire behavior. Retaining a strong symbolic interaction component, social learning theory conceptualizes social interaction as an exchange of meanings and symbols. Beyond learning definitions favorable towards the use of violence, social learning theory suggests that violent behavior can be initiated through the process of imitation (Bandura 1986), or through the anticipation of future rewards (Rotter 1954). Moreover, the theory posits that violent behavior, once initiated, will be repeated over time insofar as it is rewarded, and/or it goes unpunished (Akers 1985; 1998; Burgess and Akers 1966).

Akers’ (1998) reformulation of SSSL theory extends the social learning model by positing that social structural characteristics pattern the distribution of crime through their effect on individual-level social learning processes. Social learning theory suggests that adolescent perceptions of their economic future are formed, in part, through an assumption that their future lifestyle will be very similar to their average neighbor. Thus, when adolescents perceive that adults in their community are being rewarded financially through participation in the mainstream economy, they are more likely to conclude that their future is positive and to model what they believe to be relevant or related behavior (Wilson 1996). Examples include devaluing and avoiding the use of violence by employing social skills and practicing anger management, avoiding negative peer influences, and immersing oneself in pro-social activity such as participating in extra-curricular activity in school.

The presence of social and economic disadvantage, which implies the relative absence of adults employed in high-wage sectors of the economy, may directly increase the likelihood of violence, in part by shaping the pattern of imitation and role modeling that local adolescents adopt. Adolescents in the most disadvantaged locales may also be more likely to observe that adults in the community are not economically secure and may infer that their future opportunities are quite limited. Some research suggests that adolescents who have no positive role models and who perceive that opportunities are constricted may be more likely to seek out status in peer groups (Fagan 1993; Klein 1995). Status, in such a scenario, may be attained by demonstrating courage and physical prowess by being ready and willing to fight, including adopting an oppositional and defiant attitude set (Cohen 1955). Considerable research suggests that adolescents who perceive opportunity to be constrained become profoundly alienated and are more likely to seek status and respect in street gangs and to become involved with drug selling to generate subsistence income (Anderson 1999; Bourgois 1995; Decker and VanWinkle 1996).

Beyond a direct effect on violence, neighborhood disadvantage is conceptualized as a moderator that reinforces commitment to and intensifies the violent consequences of gang membership and drug selling. Disadvantaged neighborhoods furnish adolescents with few economic opportunities and little hope for the future – a vacuum susceptible to being filled by gangs that supply status, protection, and social reinforcement of delinquent attitudes, and drug selling which holds the prospect of income. More so than gang members in less disadvantaged locales, members residing in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods may perceive heightened competition from rivals and be more susceptible to modeling, imitating, and internalizing values, attitudes, and expectations through processes outlined in differential association and social learning theory. Consistent with the SSSL model neighborhood disadvantage may increase the frequency of adolescent violence by intensifying the perceived social and financial rewards of gang membership and illicit drug selling.

HYPOTHESES

Consistent with our approach the confluence of neighborhood disadvantage, gang membership, and drug selling produce greater participation in violence. While selling drugs augments the impact of gang membership on violence, we anticipate that participation in gangs increases the frequency of violent behavior irrespective of drug selling. Yet it is because each status is somewhat distinct, involving interaction within anti-social networks that are at least partially unique, that leads us to anticipate a multiplicative effect of gang membership and drug selling on violence. The first hypothesis predicts that gang member involvement in drug sales contributes to escalating violence:

H1: Gang members that also sell drugs during the same time period they are in the gang are most violent relative to gang members that do not sell drugs, drug sellers that are not gang members, and non-gang, non-drug sellers.

The SSSL model posits that neighborhood disadvantage intensifies the impact of gang membership and drug selling on violence by enhancing reinforcement and transmission of meanings sympathetic to gang membership and drug selling. We derive from this postulation our second hypothesis:

H2: Neighborhood disadvantage intensifies (i.e., moderates) the influence of gang membership and drug sales, and the interaction between them, on violence.

DATA AND METHODS

SAMPLE

The data are drawn from the first five waves of the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY97). This is a household based, nationally representative sample of adolescents between the ages of 12 and 16 at the time of first interview and who have been interviewed yearly since 1997. In the first stage, 100 primary sampling units (PSU) contained in NORC’s 1990 national sampling frame were randomly selected proportionate to size. Segments of adjoining blocks with at least 75 housing units were selected from each PSU, and households were randomly selected from a list of housing units in each segment. Screening interviews in each household resulted in 7,327 eligible subjects, 6,748 of whom participated, yielding a 92.1% response rate. By the fifth round, 5,919 respondents completed interviews, yielding an 87.7% retention rate.5

Because our interest lies in estimating a cross-level interaction between neighborhood disadvantage, gang membership, and drug selling we further restrict the analysis to neighborhoods in which there are at least two respondents, reducing the sample to 5,567 adolescents nested within 1,049 neighborhoods with 27,835 time-varying observations pooled over 5 waves of data (5 * 5,567). Dropping observations that are not clustered with other cases improves the reliability of the estimated between neighborhood variance component. Hazard models reveal no significant differences between the subset of cases eliminated (352 respondents) and the sample utilized in the analysis. The average number of individuals per census block-group is 5.31, ranging from 2 to 33. Regression imputation with random error components was used to replace missing values on explanatory measures (Jinn and Sedransk 1989). To ensure that the reported results are not sensitive to imputation we replicated our models using listwise deletion of cases with missing values and also mean substitution. There are no substantive differences.

LEVEL-1 MEASURES (TIME-VARYING COVARIATES)

VIOLENCE OUTCOME

The number of violent acts committed in each wave is measured with an item that asks respondents if they have attacked someone with the intention of hurting them in the past year (or since the date of last interview) and, if yes, to indicate the frequency with which they did so. The violence outcome is a count of the number of violent attacks engaged in during each wave and ranges from 0 to 99 events. Table 1 indicates that between 6% (wave 5) and 11.5% (wave 1) of the subjects reported at least one attack in each wave (see Table 1). However, a larger percentage (26.8%) reported that they attacked someone in at least one of five waves. 6 Given extensive skew, we treat the outcome as a Poisson sampling distribution with constant exposure and over-dispersion. 7

Table 1.

Percentage of sample engaging in violence, gang membership, and drug selling across the first five waves of NLSY97.

| NLSY ‘97 study wave | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | In at least one wave |

| Violence | ||||||

| 0 | 88.5 | 88.9 | 91.3 | 92.8 | 94.0 | 26.8 |

| 1 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 2.9 | |

| 2–3 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 1.9 | |

| 4–6 | 1.5 | 1.2 | .7 | .8 | .7 | |

| 7–15 | .9 | .8 | .5 | .6 | .2 | |

| 16+ | .4 | .6 | .4 | .3 | .3 | |

| Gang member | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 5.3 |

| Drug selling | 5.2 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 17.4 |

GANG MEMBERSHIP AND DRUG SELLING

The topic of gang membership is broached in the NLSY97 by asking subjects “Are there any gangs in your neighborhood or where you go to school? By gangs, we mean a group that hangs out together, wears gang colors or clothes, has set clear boundaries of its territory or turf, and protects its members and turf against other rival gangs through fighting or threats.” A few questions later each subject is asked “Have you been a member of a gang in the past year” (or since the date of the last interview after wave 1). The provision of a common definition to the entire sample immediately prior to ascertaining gang membership effectively increased the possibility that subjects residing in urban, suburban, and rural areas were working with a common conception of a gang. Gang membership is coded with a binary variable that distinguishes gang members from non-members (the referent), and reflects membership in a loosely affiliated turf gang although some gangs may have a greater orientation towards coordinated drug selling.

The definition of a street gang in the NLSY97 meshes well with the definition provided by Curry and Decker (2003) described above, and it uses the kind of filtering questions that Esbensen et al. (2001) conclude tap increasing levels of gang involvement. The NLSY97 measure does not reference core membership, but it does contain what many scholars would arguably claim are essential elements in the definition of a street gang: current membership (i.e., in the past year), relative permanence (i.e., hangs out together), organization/stability (i.e., wearing gang colors or clothes), and a delinquent focus (i.e., protection of turf by fighting or threats). With regard to the prevalence of gang membership, the NLSY97 measure compares favorably to the GREAT measure termed “organized delinquent.” Esbensen et al. (2001) found that about 5% of their sample fit that criterion. In the NLSY97 data we find that 5.3% of the sample was active as a gang member during at least one of the first five waves of data although the percentage of active gang members does not rise above 2.3% in any single wave (see Table 1).

Common wisdom suggests that over-sampling from high crime areas to maximize representation of gang members is desirable. However, an over-sample is not necessary to address the hypotheses advanced here. Optimal sample size is determined by power analysis, which takes into account the size of the effect in the population and the level of power desired. Required for the calculation is an estimate of the amount of variation in the outcome variable that is explained by the independent variable(s) of interest (i.e., the correlation squared). Given the scarcity of suitable population data we used the NLSY97 data to generate an estimate as an example. Gang membership, drug selling, and the interaction between them account for roughly five percent of the within-individual variation in self-reported violence. Assuming desired statistical power of .8 and a non-directional test at the .01 level, a sample size of approximately 227 subjects is required to observe a relationship between gang membership, drug selling, the interaction between them, and violence (see Jaccard and Becker 1990: p. 503). Our sample is comprised of 5,567 subjects, of which 295 (5.3%) were gang members in at least one of five waves. We conclude that the sample size of NLSY97 is sufficient to observe the hypothesized relationships.

Drug selling is assessed by an item that asks whether subjects sold drugs, including marijuana, cocaine, LSD, etc. in the past 12 months (or since the date of last interview). Over seventeen percent of the subjects sold drugs during at least one wave and roughly six percent did so in any single wave (see Table 1). Given our interest in the overlap between gangs and drugs, we construct dummy variable indicators that cross-classify responses to questions about gang membership and drug selling. Non-gang/non-selling respondents (reference group) are contrasted with drug sellers who are not in a gang, gang members that don’t sell drugs, and subjects who both belong to a gang and sell drugs.

LEVEL 1 CONTROL VARIABLES

Based on theory and data availability we include a set of control variables to partial out the effects of other suspected precursors and correlates of violence. Age is measured at each wave in months (from last interview) and averages about 17 years (207 months). Preliminary analysis suggests a non-linear relationship between age and violence and hence a squared term is included to capture it. The non-linear effect is consistent with what would be expected based on the age-crime curve (see Bilchik 1998), and is graphically depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Age-violence curve (NLSY’97).

Prior research suggests that residential mobility increases the risk for violence because it disrupts interpersonal networks and the social capital they provide (Ingersoll, Scamman, and Eckerling 1989). Accordingly a measure is incorporated that taps the total number of times each respondent has moved (range 0–9). On average respondents changed residence approximately two times.

Two dummy variables are included to adjust for residence in urban and suburban locales (Krivo and Peterson 1996), where the incidence of violence is expected to be greater relative to rural places (referent). On average 51% of the sample resided in suburban locales, 26% in urbanized areas, and 23% in rural locations. Deviations from the traditional, two-parent family have been shown in prior research to be consequential for children due to turmoil/disruption, depressed resources, and a less than ideal socialization environment (McLanahan and Sandefur 1994). Family structure is measured as a set of dummy variables that contrasts respondents residing with both biological parents (referent) with subjects that live in two-parent step-families, single-parent households, adoptive family settings, and in households without a parent figure. Roughly half the respondents resided with both biological parents (referent), whereas 24% lived in single parent households, 12.7% in two-parent stepfamilies, 11% in households without a parent figure, and 2% with adoptive parents.

We measure aspects of informal social control (Hirschi 1969) with binary variables that distinguish respondents who have dropped out of school, who are married, who are separated or divorced, and a covariate reflecting the number of weeks worked during the interview year. The measures of informal control show that on average 8% of youths did not complete high school (or a GED) and were not enrolled in school at the time of the interview. Most respondents were minimally involved in employment activity, on average working about 15 weeks in the previous year, and the vast majority remain unmarried (2% married). Finally, given extensive research showing drug use to be a significant predictor of adolescent violence (Farrington and Loeber 1999) we control for variation over time in each subject’s use of drugs (marijuana, cocaine, heroin) with a dummy variable that distinguishes users from non-users. A fair percentage of the sample (16%) report using drugs during at least one wave.

LEVEL-2 MEASURES (BETWEEN-PERSON)

Measurement of race is based on self-reported racial background and is represented by a binary variable that contrasts Black (15%), Hispanic (13%), Asian (2%), and others (6%) with White (64%) subjects (for a discussion of race differences see Bellair and McNulty 2005). Gender is included given well-documented (Farrington and Loeber 1999) higher rates of violence among males (female is the referent). The sample is approximately evenly split between males and females. Family income is included given evidence of an inverse relationship with violence and is measured in dollars (Bilchik 1998). The average family earns $51,510. Two covariates are included to control the influence of delinquent peers (Akers 1998), reflecting the percentage of each subject’s peers in their grade at school (or when they were in school) that are gang members and the percentage that use drugs. The response set for each item ranges from one to five with one indicating that almost none belong to a gang or use drugs and five indicating that almost all (over 90%) belong to a gang or use drugs. The mean for peer gang membership is 1.74 suggesting that on average less than 25% of subject’s peers are gang members and the mean for peer drug use is 2.21 suggesting that slightly more than 25% of peers use drugs.

LEVEL-3 MEASURES (BETWEEN-NEIGHBORHOOD)

Definition of the geographic size of a neighborhood is a debatable issue. Urban researchers often use census tracts as a proxy for neighborhood or local area. We opt instead for block-group, which is roughly one quarter the size of a tract, because census tracts become substantially larger further away from the inner city. Approximately two thirds of the subjects reside in suburban and rural contexts and thus a tract may not correspond with their conception of neighborhood. Within urban areas block-group may also be better than a tract because smaller areas are more socially homogeneous. We measure neighborhood conditions with block-group data from the 2000 U.S. Census, which are attached to individual records based on the latitude and longitude of the respondent’s home address during each interview year.

Neighborhood disadvantage is calculated in two steps. First we average the percentage of the population living below the poverty line, the percentage unemployed, and the percentage of households headed by a female across five waves for each subject. Next, we compute z-scores for each of the three averages and sum them, yielding the neighborhood disadvantage scale. There is substantial variation in the neighborhood disadvantage to which youth are exposed. The components of our normalized scale – rates of poverty, unemployment, and female-headed households – range from 0 to nearly 100% across neighborhoods. We explored adding additional variables to the scale such as percent on public assistance and percent black as some researchers have. Those variables do not improve the predictive utility of the scale. Moreover, we question the theoretical wisdom of adding extra economic variables into a disadvantage scale because, in so doing, the scale becomes weighted towards poverty which defeats the purpose of including unemployment and family structure. Adding percent black to the scale is likewise problematic because race is included in the model at the individual level, which makes the interpretation of percent black at the neighborhood level less clear. Finally, it is also the case that there has been substantial growth in the number of black middle class neighborhoods across the U.S. over the past fifty years (Patillo 2005) and that undermines the logic of including percent black in a disadvantage scale. We therefore opted for parsimony and theoretical clarity in using the three item scale.

Table 2 presents the distribution (in person-years) of gang membership and drug selling across the levels of the disadvantage index at which we evaluate effects, and the mean frequency of violence in each cell. Of the 27,835 person-year observations, in total 17,305 are between the index mean and 2 SD units below the mean, 9,465 lie between the mean and 2 SD’s above, and 1,065 observations have index values beyond 2 SD units above. The data comprise 437 person-year observations for gang members, about sixty-two percent of which are non-sellers, and 1,492 observations for non-gang respondents who sell drugs. This breakdown is consistent with prior research, indicating that drug selling is not dominated by gang members but that a sizeable proportion of gang members sell drugs (Esbensen and Huizinga 1993; Fagan 1989). The pattern of violence depicted, although descriptive, is consistent with our hypotheses. Gang members who sell drugs are more violent than gang members who don’t and non-gang drug sellers. In general, violence also increases across levels of neighborhood disadvantage.

Table 2.

Mean Frequency of Violent Attacks and Case Counts by Gang membership, Drug Selling and Levels of Neighborhood Disadvantage, Waves 1–5 NLSY97.

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean – 2 SD Units Below Mean | Mean – 2 SD Units Above Mean | GT 2 SD Units Above Mean | |

| Anti-Social Context | |||

| Not in gang, don’t sell drugs | .17 (16,086)0 | .29 (8,822) | .20 (998) |

| Not in gang, sell drugs | 1.41 (1,010) | 2.53 (447) | 2.09 (35) |

| In gang, don’t sell drugs | 3.40 (119) | 2.28 (130) | 8.92 (24) |

| In gang, sell drugs | 5.26 (90) | 12.11 (66) | 10.63 (8) |

| Total N of Cases | 17,305 | 9,465 | 1,065 |

Notes: Unadjusted coefficients. N of cases in parentheses.

METHOD

The level-1 structural model assumes the form:

| (4) |

where ηijk is the log violence event rate per unit of time i for person j in neighborhood k; π0jk is the intercept for person j in neighborhood k; αpijk are time-varying covariates that predict violence and πpjk are the corresponding level-1 coefficients indicating the association between predictors and the outcome for person j in neighborhood k; and eijk is a level-1 random effect that represents prediction error. The predictors are group mean centered to ensure that estimates of the associations between the level-1 covariates and violence are rigorous and conservative (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002:183). The procedure is a conservative safeguard against selection effects because the covariates are modeled as a deviation from their mean level across the five waves thereby netting out unmeasured, stable traits.

At level-2 random variation in the level-1 intercept is modeled with a set of person level characteristics, which can be expressed as follows:

| (5) |

where β00j is the intercept for the person-level effect π0jk in neighborhood k ; Xpij are person-level characteristics (e.g., race) used as predictors; β0pj are the corresponding regression coefficients; and Γ0ij is a level-2 random effect that represents the deviation of person jk’s level-1 coefficient (π0jk) from its predicted value based on the person-level model. Variables included at level 2 are conceptualized as controls and thus don’t bear directly on our hypotheses.

An analogous modeling process is replicated at the neighborhood level (level-3), where the intercepts or coefficients at level-1 or level-2 can be predicted by neighborhood characteristics. The general level-3 structural model can be expressed with the formula:

| (6) |

where γpq0 is the intercept in the neighborhood model for βpqk ; Wsk is our measure of neighborhood disadvantage used as a predictor of neighborhood effects; γpqs represents the extent of association between disadvantage (Wsk) and violence at level-3 (βpqk). Our interest at this stage centers on cross-level interaction effects between dummy variables reflecting gang member involvement in drug selling at level 1 and neighborhood disadvantage at level 3.

The models include two random effects: 1) a random intercept at level-2, which captures variability in the frequency of violence between persons; and 2) a random intercept at level-3, which captures between-neighborhood variation in mean violence event rates. Results of unit-specific models with robust standard errors are presented. We considered a variety of alternative specifications of the violence outcome, including treating the original and a logged frequency scale as a normal outcome. Despite substantial skew, the findings are substantively equivalent to those based on the Poisson sampling distribution. We also carefully examined our models for signs of multicollinearity by examining item inter-correlations (see Appendix 1), variance inflation factors (VIFs), and whether standard errors increase across equations. None of the VIFs came close to exceeding the critical value of 4.0 (Fisher and Mason 1981:108) and the other tests also indicate that multicollinearity is not at play in the analysis.

Appendix 1.

Correlation Matrix (variable names listed at bottom).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| 2 | 0.3109 | 1.0000 | |||||

| 3 | −0.0544 | −0.0048 | 1.0000 | ||||

| 4 | 0.0412 | 0.0796 | 0.3910 | 1.0000 | |||

| 5 | 0.0246 | 0.0531 | 0.1519 | 0.7101 | 1.0000 | ||

| 6 | 0.0326 | 0.0260 | 0.0113 | 0.0691 | 0.0312 | 1.0000 | |

| 7 | −0.0270 | −0.0314 | −0.0197 | −0.0725 | −0.0332 | −0.6022 | 1.0000 |

| 8 | 0.0334 | 0.0286 | −0.0525 | 0.0378 | −0.0004 | −0.0034 | 0.0099 |

| 9 | 0.0585 | 0.0515 | −0.0550 | 0.0470 | 0.0044 | 0.0965 | −0.0508 |

| 10 | 0.0144 | 0.0102 | −0.0359 | 0.0026 | −0.0071 | 0.0056 | −0.0007 |

| 11 | 0.0071 | 0.0271 | 0.3279 | 0.3580 | 0.1851 | 0.0692 | −0.0731 |

| 12 | 0.0772 | 0.0990 | 0.1562 | 0.2613 | 0.1631 | 0.0521 | −0.0425 |

| 13 | −0.0424 | −0.0225 | 0.5554 | 0.1810 | 0.0597 | −0.0210 | 0.0188 |

| 14 | −0.0127 | −0.0072 | 0.1786 | 0.1635 | 0.0852 | 0.0038 | −0.0137 |

| 15 | 0.1879 | 0.1449 | 0.1326 | 0.1121 | 0.0568 | 0.0185 | 0.0127 |

| 16 | 0.0367 | 0.0328 | −0.0022 | 0.0549 | 0.0232 | 0.3048 | −0.2802 |

| 17 | 0.1961 | 0.1331 | 0.0424 | 0.0611 | 0.0354 | 0.0089 | 0.0102 |

| 18 | 0.1422 | 0.0973 | −0.0231 | 0.0198 | 0.0065 | 0.0159 | −0.0170 |

| 19 | 0.2252 | 0.0982 | −0.0205 | 0.0192 | 0.0114 | 0.0111 | −0.0088 |

| 20 | −0.0025 | 0.0189 | 0.0014 | 0.0129 | 0.0073 | 0.0634 | −0.0645 |

| 21 | 0.0525 | 0.0098 | −0.0190 | −0.0062 | −0.0033 | 0.0368 | −0.0237 |

| 22 | 0.0391 | 0.0189 | 0.0004 | 0.0033 | 0.0045 | 0.0383 | −0.0212 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| 9 | −0.2154 | 1.0000 | |||||

| 10 | −0.0531 | −0.0786 | 1.0000 | ||||

| 11 | −0.1338 | −0.1979 | −0.0488 | 1.0000 | |||

| 12 | 0.0011 | 0.0434 | 0.0095 | 0.1909 | 1.0000 | ||

| 13 | −0.0148 | −0.0672 | −0.0402 | 0.2131 | 0.0404 | 1.0000 | |

| 14 | −0.0445 | −0.0540 | −0.0172 | 0.3051 | 0.1177 | 0.1045 | 1.0000 |

| 15 | 0.0217 | 0.0473 | −0.0024 | 0.0566 | 0.0844 | 0.0972 | −0.0252 |

| 16 | −0.0256 | 0.1424 | 0.0201 | 0.0735 | 0.0855 | −0.0774 | 0.0014 |

| 17 | 0.0166 | 0.0320 | 0.0046 | 0.0228 | 0.0476 | 0.0537 | −0.0154 |

| 18 | 0.0097 | 0.0340 | 0.0084 | 0.0029 | 0.0426 | −0.0259 | −0.0035 |

| 19 | 0.0099 | 0.0125 | 0.0213 | 0.0205 | 0.0413 | −0.0246 | −0.0106 |

| 20 | −0.0061 | 0.0073 | −0.0104 | 0.0276 | 0.0314 | −0.0212 | 0.0042 |

| 21 | 0.0089 | 0.0150 | 0.0025 | −0.0026 | 0.0080 | −0.0176 | −0.0008 |

| 22 | 0.0008 | 0.0105 | 0.0026 | −0.0039 | 0.0037 | −0.0060 | −0.0004 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| 16 | −0.0201 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| 17 | 0.3950 | −0.0278 | 1.0000 | |||||

| 18 | 0.0564 | 0.0397 | −0.0237 | 1.0000 | ||||

| 19 | 0.1370 | 0.0031 | −0.0184 | −0.0078 | 1.0000 | |||

| 20 | −0.0730 | 0.1997 | −0.1322 | 0.0031 | 0.0024 | 1.0000 | ||

| 21 | −0.0014 | 0.1496 | −0.0062 | 0.2632 | −0.0020 | 0.0008 | 1.0000 | |

| 22 | 0.0066 | 0.0749 | −0.0008 | −0.0003 | 0.0416 | 0.0001 | −0.0001 | 1.0000 |

1 Violent Attacks

2 Prior attack

3 Age in months

4 # of residential moves

5 Squared # of residential moves

6 Urban

7 Suburb

8 Two parent, step

9 One parent

10 Adopted

11 Not living with a parent figure

12 Not in school, no diploma/GED

13 # of weeks worked

14 Married

15 Used drugs

16 Disadvantage Index

17 Not in gang, sell drugs

18 In gang, don’t sell drugs

19 In gang, sell drugs

20 Disadvantage * Not in gang, sell drugs

21 Disadvantage * In gang, don’t sell drugs

22 Disadvantage * In gang, sell drugs

We also examined the issue of causal order between gang membership, drug selling, and violence prior to deciding which analysis to present. All of the level 1 variables are derived from identically worded questions asked across rounds one through five. This approach is consistent with previous research that shows violence increases during the period that subjects are current gang members (Thornberry et. al. 2003) relative to before or after gang membership. Unfortunately this strategy can not definitively establish causal order because the data don’t contain the date of gang membership or the dates when violence occurred. Thus, it is known that the violent acts reported occurred during the same year that the subject was a gang member or was selling drugs but it is not possible to determine whether all of the violence engaged in by current gang members occurred subsequent to joining a gang within that year or subsequent to the onset of drug selling.

Several methods were used to ensure that the findings are rigorous given this issue. First, an independent variable reflecting attacks committed in the previous wave was included with no substantive changes to the pattern of findings. Given that our models assess how changing statuses influence changing violence involvement, including prior attacks serves to control for ceiling effects (i.e., regression towards the mean) because subjects who have previously reported prior attacks are likely to reduce violence involvement in subsequent rounds while those who have never reported an attack are most likely to continue their non-involvement. Lagging the gang member and drug selling indicators (such as measuring them one year prior to the violence outcome) is a potential empirical solution that also does not alter our substantive conclusions, but theoretically it is less defensible because violence is highest while subjects are active gang members relative to one year later after the subject has probably left the gang. Recall that most gang members enter a gang for a short period of time and most typically soon depart. Finally, we estimated a first order auto-regressive correction of the level-1 residuals to account for correlated error generated by the potential omission of a common set of predictors from the violence equation across each wave. This alternative modeling again produced no substantive changes to the findings presented below.

THREE-LEVEL HIERARCHICAL MODEL

Table 3 presents Poisson regressions of the frequency of adolescent violent behavior. The upper panel displays the unit-specific fixed effects and the lower panel displays random effects. Model 1 is the unconditional growth model of the frequency of violence across the five waves. The estimated mean (within neighborhood) log event rate of violence is −2.392 (p < .01), indicative of the overall low frequency of violence. The age (in months) squared coefficient is significant indicating that the growth trajectory is non-linear. This reflects the age-crime curve of increasing involvement in violence during early adolescence, a peak during mid-adolescence, followed by declining involvement in late adolescence (see Figure 1). The variance components for the level-2 and level-3 intercepts are statistically significant, indicating significant between-person and between-neighborhood variability in violence event rates. As is commonly the case the bulk of variance (64.9%) in violence involvement is between persons, although 5.4% is between-neighborhoods and 29.7% represents temporal variation at level-1.

Table 3.

Poisson regression of violent attacks on gang membership, drug selling, and neighborhood disadvantage a

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.392*** | −3.055*** | −3.038*** | −3.059*** |

| Neighborhood Disadvantage (level-3 between-neighborhood) | .063*** | .052*** | ||

| Level-2 Between-Person Control Variables | ||||

| Black b | .442*** | .284** | .288** | |

| Hispanic | .144 | .061 | .069 | |

| Asian | −.345 | −.337 | -.346 | |

| Other | −.006 | −.025 | −.026 | |

| Male c | .827*** | .804*** | .804*** | |

| Peer-Gang | .243*** | .233*** | .235*** | |

| Peer-Drug | .179*** | .175*** | .176*** | |

| Family Income j | −.002** | −.002** | −.002** | |

| Level-1 Time Varying Control Variables | ||||

| Age in months | .092*** | .059*** | .033 | .026 |

| Age in months squared | −.0002*** | −.0002*** | −.0001** | −.0001* |

| # of residential moves | .054 | .023 | .023 | |

| Urban d | .432 | .404 | .384 | |

| Suburb | −.034 | −.101 | −.073 | |

| Two parent, stepe | .348 | .303 | .344 | |

| One parent | .552** | .517** | .557** | |

| Adopted | .210 | −.203 | −.197 | |

| Not living with a family figure | .201 | .240 | .289 | |

| Not in school, no diploma f | .112 | .089 | .078 | |

| # of weeks worked | .003 | .0001 | .0001 | |

| Married g | −.044 | .013 | −.010 | |

| Seperated/divorced | .777* | .878** | .844** | |

| Use drugs h | 1.235*** | .703*** | .712*** | |

| Level-1 Time Varying x Level-3 Between-Neighborhood | ||||

| Not in gang, sell drugs i | 1.220*** | 1.120*** | ||

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | .014 | |||

| In gang, don’t sell drugs | 1.158*** | .845** | ||

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | .249*** | |||

| In gang, sell drugs | 2.031*** | 1.881*** | ||

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | .196* | |||

| Random Effect | Variance Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level-1, etij | 1.190 | 1.153 | 1.095 | 1.062 |

| Level–2, Intercept, Γ0ij | 2.595*** | 2.427*** | 2.373*** | 2.407*** |

| Level–3, Intercept, μ00 | .216*** | .263*** | .243*** | .245*** |

Notes:

(p < .10);

(p < .05);

(p < .01).

Unit specific, robust standard errors.

White is the referent.

female is referent.

rural is referent

both biological parents is referent.

in school or have diploma is referent.

not married is referent.

did not use drugs is referent.

not in gang, don’t sell drugs is referent

family income multiplied by 1,000 to reduce places to the right of the decimal.

We turn now to a baseline equation in Model 2 that includes level 1 and 2 control variables, the effects of which are consistent with expectations. The effect of being Male is by far the largest of the person-level predictors. African American subjects are at a significantly higher risk of violence, as are subjects residing in households with diminished income and whose peers are more gang and drug involved. Family structure indictors reveal that youth who reside in single-parent households engage in violence at a higher rate than youth living in households with both biological parents, as do subjects who are separated or divorced. Finally, use of drugs substantially raises the likelihood of violent attacks.

Models 3 and 4 test the hypotheses that gang membership and drug selling jointly increase the frequency of violence (H1), and that an increase in neighborhood disadvantage intensifies the influence of gang membership and drug selling, and the intersection between them, on violence (H2). Most strikingly and supportive of H1, gang membership and selling drugs interact to substantially increase violent attacks. Being a gang member who sells drugs raises the frequency of violent attacks by 2.031 relative to person-years when not in a gang and not selling drugs. Drug-selling gang members are nearly twice as violent as non-selling gang members and non-gang drug sellers, and those differences are statistically significant. A rise in attacks is also evident among gang members not involved in drug selling and among non-gang drug sellers, but these groups exhibit roughly equivalent (i.e., not statistically different) levels of violence (1.158 vs. 1.220). The neighborhood disadvantage index also evidences the expected positive effect on violent attacks.

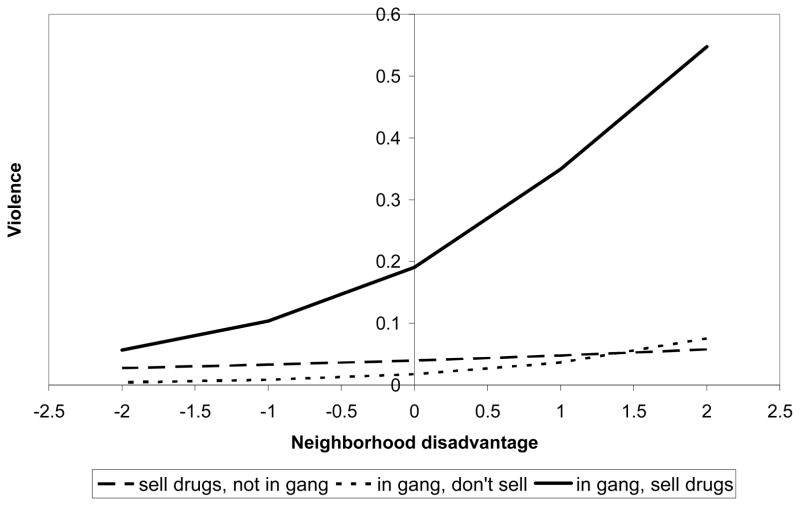

Model 4 incorporates cross-level interactions representing the intersection of neighborhood disadvantage, gang membership, and drug selling, providing a test of H2 derived from SSSL theory. Specifically, we assess whether an increase in disadvantage intensifies the effect of gang membership and drug sales on the frequency of violent attacks. Consistent with H2, the interaction is significant and pronounced for gang members, reflecting heightened violence for those residing in the most disadvantaged environments. The coefficients for the product terms indicate that the rise in violent attacks associated with gang membership (whether selling drugs or not) is greater in neighborhoods with higher levels of structural disadvantage.

Figure 2 summarizes the effect of gang membership and drug selling at levels of neighborhood disadvantage ranging from 2 standard deviations above and below the mean. At the mean level of disadvantage, the effects correspond to those displayed in Table 3, Model 4 although they have been exponentiated to reflect actual counts. The figure clearly implicates the role of gang member participation in drug selling in promoting violent behavior, particularly in the more disadvantaged locales. Also evident is the roughly equivalent violence involvement of non-selling gang members and non-gang drug sellers across levels of disadvantage. Figure 2 drives home the main point of this paper that gang members who sell drugs are most violent and that their violence increases in disadvantaged locales.

Figure 2.

Simple slope of gang membership and drug selling on violence by neighborhood disadvantage.

DISCUSSION

Prior gang research suggests that gang member involvement in drug selling does not necessarily lead to increased violence, and that the relationship between gang membership, drug selling, and violence is unrelated to the neighborhoods in which subjects reside. This paper revisits those issues and tests two hypotheses regarding the intersection of neighborhood disadvantage, gang membership, drug selling, and violence: (H1) that gang members who sell drugs are most violent; and (H2) that increasing neighborhood disadvantage intensifies the influence of gang membership and drug selling on the frequency of violence.

Our conceptual model is informed by Akers’ (1998) SSSL theory, which has its roots in neighborhood structure and argues that violent behavior in disadvantaged neighborhoods is an effect in part of exposure to anti-social learning in gang and drug subcultures. The analysis expands upon Akers’ formulation by explicating the mutually conditioning influences on violence of neighborhood disadvantage, gang membership, and drug selling. We draw on five waves of data from the NLSY97 and estimate a three-level hierarchical model. Consistent with H1 we find drug selling to be a major facilitator of violence. Gang members who report selling drugs engage in violence at a significantly higher rate than non-selling gang members and non-gang drug sellers. Supportive of H2 gang members who sell drugs are by far most violent when they reside in highly disadvantaged locales. These findings support the SSSL model and our conceptualization that gang membership and drug selling fill the vacuity of economic opportunity and isolation from mainstream society within disadvantaged neighborhood environments.

The findings clearly contradict prior research suggesting that gang member involvement in drug sales does not necessarily increase the frequency of violent behavior (e.g., Fagan 1989; Klein et al. 1991; Howell and Decker 1999). One explanation for the divergent results is the national scope of the NLSY97 data collection, which creates substantial variance in gang members and in neighborhood context. Prior research on gang by neighborhood interaction effects is limited to data collected in a single urban area and thus is less likely to uncover interaction or neighborhood effects despite strong measurement of individual level processes. The findings are consistent with research that indicates disadvantaged neighborhoods provide few legitimate economic opportunities and which suggests that gang members who sell drugs have fewer alternatives by which to earn income. This reinforces members’ commitment to gang membership, drug sales, and to the retaliatory violence that is often necessary to protect what they perceive to be theirs, and is consistent with Fagan’s (1989) suggestion that variation in gang violence reflects both the marginalization of gang members and of the neighborhoods in which they reside. When gang members sell drugs they are most violent and even more so when they reside in disadvantaged contexts. The findings suggest that the strong relationship between gang membership and violence revealed in prior research is confounded by the heightened frequency of violence among gang members that sell drugs versus gang members that don’t, and by the neighborhood contexts in which they reside.

The analysis, although consistent with hypotheses, should be treated with some caution given limitations inherent to large national data sets. There are several issues that can not be adjudicated here. For instance, the definition of a gang is a central and contested issue in the gang literature about which there is much discussion and limited consensus. Thrasher (1927) identified several defining features that distinguish gangs including a spontaneous origin, solidarity, tradition, and defense of geographical turf. Absent from Thrasher’s (1927) definition is involvement in delinquency or violence, a glaring limitation to some because otherwise that definition does not conceptually exclude adolescent groups such as some fraternities that are really not gangs (Bursik and Grasmick 1993). Klein (1971) made a strong case for the inclusion of that criterion and his work, although still debated, has had an enduring influence on gang research. Some researchers, such as Curry and Decker (2003: p. 3–6), blend the insights of Thrasher (1926) and Klein (1971) and define a gang as a group that is relatively permanent, that has symbols such as colors, that uses non-verbal communication such as graffiti, that claims turf, and that commits crime. Although disagreements have not been resolved Curry and Decker’s (2003) definition of a gang is assumed to provide a reasonable working definition.

The topic of street gang conceptualization and measurement in social surveys is directly addressed by Esbensen et al. (2001). At issue is whether the criteria used to define gang membership influences estimates of the size of the gang problem and whether survey gang measures exhibit criterion validity. They found that the prevalence of gang membership progressively declined when respondents were presented with increasingly restrictive definitions of gang membership: were you ever in a gang (17%), are you currently in a gang (9%), are you currently in a delinquent gang (8%), are you currently in an organized delinquent gang (5%), and are you currently a core gang member (2%). The findings suggest that accurate measurement of gang member status is dependent on restrictive questions that filter out individuals whose self-nominated gang membership may be questionable. Regarding the use of survey methods to measure gang membership they conclude (p. 124) that “the self-nomination technique is a particularly robust measure of gang membership capable of distinguishing gang from non-gang youth.” The NLSY97 measurement of gang membership, while conforming to the important criteria set out in the literature reviewed above, potentially under-counts individuals who don’t perceive their gang in the same terms but whose behavior otherwise fits our conception of a gang member. We have no reason to believe that the definition of a gang used in the NLSY97 is confounding the analysis. Future research will be necessary to uncover how gang structure (i.e., loosely affiliated versus more formal) impacts the nature of drug selling and violence among members. Yet, NLSY97 provides a baseline to address the basic questions we pose and thus moves the literature a step towards understanding this complex issue.

The intersection of disadvantage, gang membership, drug selling, and violence raises related issues over the nature of drug sales by gang members and the nature of gang member violence. Some gang scholars view the nature and structure of street gangs as approximating a formal-rational organization. In this view street gangs possess an organizational structure consisting of a hierarchy of individuals serving specified roles, a normative structure emphasizing allegiance to the goals of the gang as a unit rather than to a particular clique or set within, and a method of enforcing norms. Prior research indicates that some street gangs sell drugs in a manner approximating a formal-rational style (Sanchez-Jankowski 1991; Skolnick 1990; Venkatesh 1997).

However, that research is somewhat overshadowed by a larger volume of studies indicating that most drug-selling by individual gang members is not controlled or coordinated by gang leaders. Numerous scholars maintain that the territorial, status orientation and loosely confederated, informal structure of most street gangs undermines coordinated drug sales and corporate behavior among members. Fagan (1989), for instance, gathered self-report data from 151 gang members in three cities and reached that conclusion. He found that gang members in general were not much more likely to sell drugs than non-members, and that drug selling in “party” gangs lacked the type of structure posited by the formal-rational model (also see Fagan 1992).

Klein et al. (1991) drew from arrest records and compared gang member involvement in crack sales to that of non-members. Contradicting the image of gangs as corporate actors, results suggested that differences in the nature of crack sales by gang members versus non-members were relatively small and varied little by race. Acknowledging that gang members often sell drugs, they concluded that gang membership and drug selling are distinct issues because most drug sales are not coordinated by street gangs. Rather, gang members who sell drugs do so based on their own initiative (also see Hagadorn 1988; Decker and Van Winkle 1994). The NLSY97 provided respondents with a clear definition of a loosely affiliated turf gang prior to inquiring about membership, but did not inquire about the purpose or organization of the gang or the location of members in the gang’s hierarchy (i.e., hardcore member versus peripheral member).

The NLSY97 focuses on gang members, not gangs. As a result NLSY97 data can not address whether street gangs control or dominate drug markets or whether gang members in the data belong to a loosely confederated gang or to a gang that fits the NLSY97 definition but which also exhibit some organization towards drug selling. Yet, the theoretical approach adopted predicts that gang members who sell drugs will be more violent than those who don’t regardless of whether their gang is organized to sell drugs or is loosely integrated and primarily concerned with status, protection, and maintenance of turf. We presuppose that gang members who sell drugs in the context of a more organized drug gang are likely to be constrained from violence relative to turf gang members who sell because of pressure from within the gang to avoid unwanted attention from the police, but that members who sell drugs in either type of gang are more similar in violence to each other than to gang members that don’t sell drugs or to non-gang drug sellers. To the extent that gang members who sell drugs in the NLSY97 are more likely to belong to drug gangs with some level of formal organization, the mean difference in violence between gang members who sell drugs and those that don’t is most likely under-estimated. Relating to drug sales another issue is that NLSY97 does not distinguish which drugs are being sold even though there are good reasons to believe that crack sales produce more systemic violence than marijuana sales. Obviously, much more research is necessary before those issues can be unraveled.

In addition, the measurement of violence in NLSY97 does not distinguish whether the violence reported is instrumental and thus carried out to improve economic or social standing or is expressive such as to vent anger and frustration. We presuppose that violence committed by gang members arises out of a mixture of expressive and instrumental motivations. The SSSL theoretic model that informs this research asserts that gang members who sell drugs are more likely to engage in a diffuse pattern of violence. The assumption of diffuse violence suggests that both instrumental and expressive violence will increase when an individual’s status changes to gang member and drug seller with no a-priori expectation about which form is more likely although in general we assume that both types of violence will increase.

Finally, and more generally, the findings provide a boost for neighborhood approaches. It is well known that the influence of neighborhood processes on the average individual’s self-reported behavior revealed in many prior studies is significant, but small in magnitude relative to individual-level predictors (Liska 1990). As a result many scholars have questioned the importance of neighborhood relative to individual approaches. That neighborhood disadvantage intensifies the effect on violence of variables such as gang membership and drug selling, variables that are among the strongest predictors of violence in the literature, suggests the importance of Akers’ SSSL model but also neighborhood approaches to crime more generally. Clearly, additional multi-level research is needed to illuminate the mechanisms that account for the association between community disadvantage and violence outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by grant #5 R03 DA15717-02 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIH). We also thank the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Center for Human Resources Research (CHRR) at The Ohio State University for their assistance with data. The views contained here reflect those of the authors.

Footnotes

Throughout the manuscript we frequently refer to the relationship between “neighborhood disadvantage,” “gang membership,” “drug selling,” and “violence.” When those terms are used we are actually referring to the relationship between current gang membership and/or current drug selling and the current frequency of violence. We avoid using the word “current” in the text because its continued use throughout the manuscript is repetitious.

When we refer to the effect of neighborhood disadvantage in the text we are referring to the socioeconomic conditions in proximity to the residential address, but not necessarily the socio-economic conditions where drugs are being sold.

Goldstein (1985) defines systemic violence as “traditionally aggressive patterns of interaction within the system of drug distribution and use.”

Subculture is defined herein as a network of individuals involved in drug selling or who are gang members. Sometimes drug and gang subcultures are partially overlapping such as when gang members sell drugs.

NLSY97 over-sampled African American and Hispanic respondents. We elected against using the over-sample because the analytic focus of the paper does not specifically address race/ethnicity. The so called “cross-sectional” sample, which we analyze here, is also preferred because it is self-weighted -- the U.S. population 12–16 is sampled with probability of selection proportionate to size. The results are substantively identical when the over-sample is included in our analysis.

The violence measure available to us does not distinguish whom attacks are directed towards or why they were carried out. For some research purposes, such as determining the precise proportion of violence that is gang-related or instrumental, this could be an important limitation. However, the issue is not particularly relevant in this analysis because, as discussed in the section on key issues above, the SSSL model predicts increased violence upon the confluence of gang membership, drug selling, and neighborhood disadvantage and is agnostic about whom it is directed towards or why.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Contributor Information

Paul E. Bellair, The Ohio State University

Thomas L. McNulty, The University of Georgia

References

- Akers Ronald L. Deviant Behavior: A Social Learning Approach. 3. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Akers Ronald L. Social Learning and Social Structure: A General Theory of Crime and Deviance. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Akers Ronald L, Krohn Marvin D, Lanza-Kaduce Lonn, Radovich Marcia. Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory. American Sociological Review. 1979;44:636–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Elijah. Code Of The Street. New York: W.W. Morton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura Albert. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Battin Sara R, Hill Karl G, Abbott Robert D, Catalano Richard C, Hawkins David J. The contribution of gang membership to delinquency beyond delinquent friends. Criminology. 1998;36:93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bellair Paul E, McNulty Thomas L. Beyond the Bell Curve: Community Disadvantage and the Explanation of Black-White Differences in Adolescent Violence. Criminology. 2005;43:1135–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Bilchik Shay. Serious and violent juvenile offenders. Washington D.C: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois Phillippe. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El-Barrio. UK: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess Robert L, Akers Ronald L. A differential association-reinforcement theory of criminal behavior. Social Problems. 1966;14:128–147. [Google Scholar]

- Curry G David, Decker Scott H. Confronting Gangs: Crime and Community. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Decker Scott H, Van Winkle Barrik. Slinging dope: The role of gangs and gang members in drug sales. Justice Quarterly. 1994;11:583–604. [Google Scholar]

- Decker Scott H, Van Winkle Barrik. Life in the Gang: Family, Friends, and Violence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Esbenson Finn-Aage, Huizinga David. Gangs, drugs, and delinquency in a survey of urban youth. Criminology. 1993;31:565–587. [Google Scholar]

- Esbenson Finn-Aage, Winfree LT, Jr, He N, Taylor TJ. Youth gangs and definitional issues: when is a gang a gang, and why does it matter? Crime and Delinquency. 2001;(47):105–130. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan Jeffrey. The social organization of drug use and drug dealing among urban gangs. Criminology. 1989;27:633–669. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan Jeffrey. Drug selling and licit income in distressed neighborhoods: The economic lives of street-level drug users and dealers. In: Harrell A, Peterson’s G, editors. Drugs, Crime, and Social Isolation. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington David P, Loeber Rolf. Transatlantic replicability of risk factors in the development of delinquency. In: Cohen P, Slomkowski C, Robbins LN, editors. Historical and Geographical Influences on Psychopathology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 299–329. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein Paul J. The drugs/violence nexus: A tripartite conceptual framework. Journal of Drug Issues. 1985;14:493–506. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson Michael R, Hirschi Travis. A General Theory of Crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hagadorn John M. People and Folks: Gangs, Crime, and the Underclass in a Rust Belt City. Chicago: Lakeview press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Gina P, Thornberry Terence P, Lizotte Alan J. The gang facilitation effect and neighborhood risk: Do gangs have a stronger influence on delinquency in disadvantaged areas? In: Short James F, Hughes Lorine A., editors. Studying Youth Gangs. Oxford, UK: AltaMira Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi Travis. Causes of Delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Howell James C, Decker Scott H. The youth gangs, drugs, and violence connection. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll Gary M, Scamman James P, Eckerling Wayne D. Geographic Mobility and Student Achievement in an Urban Setting. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 1989;11:143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard James, Becker Michael A. Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Pacific Grove, CA: Wadsworth; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs Bruce A. Robbing Drug Dealers: Violence Beyond the Law. NY: Aline de Gruyter; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs Bruce A, Wright Richard. Street Justice: Retaliation in the Criminal World. NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston Jack, DiNardo John. Econometric Methods. 4. NY: McGraw-Hill; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Klein Malcolm W. Street Gangs and Street Workers. Englewood, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Klein Malcolm W, Maxson Cheryl L, Cunningham Lea C. Crack, street gangs, and violence. Criminology. 1991;29:623–650. [Google Scholar]

- Klein Malcolm W. The American Street Gang: Its Nature, Prevalence, and Control. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Krivo Lauren, Peterson Ruth. Extremely Disadvantaged Neighborhoods and Urban Crime. Social Forces. 1996;75:619–648. [Google Scholar]

- Liska Allen E. The Significance of Aggregate Dependent Variables and Contextual Independent Variables for Linking Macro and Micro Theories. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1990;53:292–301. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan Sara, Sandefur Gary. Growing Up With A Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pattillo Mary. Black middle-class neighborhoods. Annual Review of Sociology. 2005;31:305–29. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush Steven, Bryk Anthony S. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld Richard Bray, Timothy M, Egley Arlin. Facilitating Violence: A Comparison of Gang-Motivated, Gang-Affiliated, and Nongang Youth Homicides. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1999;4:495–516. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter Julian. Social Learning and Clinical Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Jankowski Martin. Islands in the Street: Gangs and American Urban Society. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Short James F, Jr, Strodtbeck Fred L. Group Process and Gang Delinquency. Chicago: University of Chicago press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Skolnick Jerome. The social structure of street drug dealing. American Journal of Police. 1990;9:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Spergal Irving A. Racketville, Slumtown, and Haulburg. Chicago: University of Chicago press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland Edwin. Criminology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry Terrance, Krohn Marvin D, Lizotte Alan J, Chard-Wierschem Deborah. The role of gangs in facilitating delinquent behavior. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1993;30:55–87. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry Terrance P, Krohn Marvin D, Lizotte Alan J, Smith Carolyn A, Tobin Kimberly. Gangs and Delinquency in Developmental Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tita George, Ridgeway Greg. The Impact of Gang Formation on Local Patterns of Crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2007;44:208–237. [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher Frederick. The Gang. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson William J. The Truly Disadvantaged. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson William J. When Work Disappears. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]