Abstract

Inverted urothelial papilloma (IUP) is an uncommon neoplasm of the urinary bladder with distinct morphological features. Studies regarding the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in the etiology of IUP have provided conflicting evidence of HPV infection. Additionally, little is known regarding the molecular alterations present in IUP or other urothelial neoplasms which might demonstrate inverted growth pattern like low-grade or high-grade urothelial carcinoma. Here, we evaluated for the presence of common driving somatic mutations and HPV within a cohort of inverted urothelial papillomas, (n=7) non-invasive low-grade papillary urothelial carcinomas with inverted growth pattern (n=5,) and non-invasive high-grade papillary urothelial carcinomas with inverted growth pattern (n=8). HPV was not detected in any case of inverted urothelial papilloma or inverted urothelial carcinoma by either ISH or by PCR. Next generation sequencing identified recurrent mutations in HRAS (Q61R) in 3 of 5 inverted urothelial papillomas, described for the first time in this neoplasm. Additional mutations of Ras pathway members were detected including HRAS, KRAS, and BRAF. The presence of Ras pathway member mutations at a relatively high rate suggests this pathway may contribute to pathogenesis of inverted urothelial neoplasms. Additionally, we did not find any evidence supporting a role for HPV in the etiology of inverted urothelial papilloma.

Keywords: HRAS, Human papilloma virus, Inverted urothelial papillomas, Next generation sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Inverted urothelial papilloma (IUP) is an uncommon urothelial neoplasm (<1% of all urothelial tumors) with a generally accepted benign clinical course and a distinctive histomorphology. Periodic reports have linked rare cases of IUP with recurrence (1.37%), as well as synchronous (1.43%) and/or metachronous (1.15%) urothelial carcinomas (UCA) (Reviewed in [1]) leading to ambiguity with regards to the biologic potential of IUP; however, several recent studies have not shown an increased risk of UCA [2, 3].

A limited number of IUP studies using single gene based assays have identified mutations in FGFR3, in 9.8% to 45% of cases [4, 5]. However, IUP rarely show other features associated with UCA such as p53 overexpression, high Ki-67 expression, and chromosomal abnormalities highlighted by UroVysion FISH [3, 6]. To date, analysis of the breadth and depth of alterations in IUP across multiple oncogenes and tumor suppressors has not been reported.

The unclear pathogenesis of IUP led to investigation of a causal role for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, with varying results. While two studies showed high rates of HPV infection in IUP by PCR [7, 8] along with concordant overexpression of p16 [8], two additional studies show HPV infection to be absent or rare in IUP [9, 10].

Hence, we sought to investigate a cohort of IUP, along with both noninvasive low-grade and high-grade papillary UCA with inverted growth pattern utilizing a highly multiplexed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) approach (AmpliSeq) to amplify the coding regions surrounding recurrently mutated genomic hot spots in the 50 most frequently mutated oncogenes and tumor suppressors in human cancer. This was followed by barcoding of the individual samples and next generation sequencing using the IonTorrent Personal Genome Machine. In parallel, we examined the same cohort with regards to their HPV status using a multi-pronged approach including immunohistochemistry for p16, in-situ hybridization and a separate PCR for detection of high risk HPV since the Ampliseq panel does not amplifiy exogenous virus.

METHODS

Tissue samples

20 cases of inverted urothelial tumors (diagnosed between 1992 and 2012) were selected from the archives of the University of Michigan following approval from the Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for these samples was obtained prior to acquisition. Slide review (A.S.M. and R.M.) using the International Consultation on Bladder cancer 2012 update of the 2004 WHO diagnostic criteria [11, 12] confirmed the diagnosis of IUP in seven cases; inverted papillary urothelial carcinoma, low grade, noninvasive (INV-LG) in five cases; and inverted papillary urothelial carcinoma, high grade, noninvasive (INV-HG) in eight cases. No IUP cases had a history of synchronous or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Available clinicopathologic data was obtained from medical records.

p16 Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for p16 was performed using the Ventana Benchmark System (Ventana Medical Systems; Tucson, Arizona) on 4µm thick formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections from all cases of IUP and INV-LG, and four of eight cases of INV-HG (four cases of INV-HG did not contain sufficient tissue for analysis). Standardized staining using pre-diluted mouse monoclonal p16INK4a antibody (E6H4), (Ventana Medical Systems; Tucson, Arizona) was followed by secondary dectection using horseradish peroxidase congjugated, polyclonal goat anti-mouse antibody. Target protein expression was developed using Ultraview DAB polymer (Ventana Medical Systems; Tucson, Arizona), with hematoxylin as counterstain. Appropriate positive and negative controls were included. p16 positivity was defined as strong nuclear immunoreactivity.

Human papillomavirus in-situ hybridization

Chromogenic in-situ hybridization to detect HPV DNA was performed using the high-risk HPV family 16 probe cocktail from Ventana Medical Systems (including HPV genotypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 66) on six of seven cases of IUP, all cases of INV-LG, and four of eight cases of INV-HG. One case of IUP and four INV-HG did not have sufficient tissue present for evaluation. HPV DNA signals were visualized following hybridization on 4µm thick FFPE sections using ISH I View Blue Plus detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems; Tucson, Arizona), with hematoxylinas counterstain. HPV positivity was defined as strong, dark blue dot-like staining. Cervical tissue with HPV related squamous carcinoma was used as a positive control.

Human papillomavirus analysis and typing

HPV detection and typing was performed via PCR of genomic DNA, followed by direct sequencing. Ten µm-thick FFPE sections (8–10 per sample) from all cases of IUP and INV-LG, and four of eight cases of INV-HG were deparaffinized, followed by DNA extraction using a digestion buffer containing 2 mg/ml proteinase K. Four INV-HG did not have sufficient tissue to be used for evaluation. GP5+/GP6+ and My09/My11 consensus primers were used for HPV DNA detection [13]. HPV-negative samples were confirmed by a second PCR assay and DNA quality was verified using HPRT1 and β-globin sequences. PCR products were purified with the GENECLEAN III Kit (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and directly Sanger sequenced. DNA sequences were compared with GenBank sequences using the BLAST Program at the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Targeted Next Generation Sequencing

Ten µm FFPE sections (8–10 per sample) with high estimated tumor content (50–80% tumor nuclei) were cut from five of seven cases of IUP, all five cases of INV-LG, and five of eight cases of INV-HG. Two IUP and three INV-HG did not have sufficient tumor content for analysis. DNA and RNA was isolated using the QiagenAllprep FFPE DNA/RNA kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (except for extending xylene incubation to five minutes and centrifugation during deparaffinization to five minutes) and quantified using the Qubit 2.0fluorometer (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA). Barcoded libraries were generated from 10ng of DNA per sample using the Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot v2 Panel (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA) and the Ion Ampliseq library kit 2.0 (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions with barcode incorporation. A complete list of the targeted genes and mutations can be found at http://tools.invitrogen.com/downloads/cms_106003.csv. Templates were prepared using the Ion PGM Template OT2 Kit v2 (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing of multiplexed templates was performed using the IonTorrent Personal Genome Machine (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA) on Ion 316 chips using the Ion PGM 200 Sequencing Kit v2 (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Analysis was performed in Torrent Suite 3.6, with alignment by TMAP (version 3.6.39) using default parameters, and variant calling by Torrent Variant Caller plugin (version 3.6.63335) using default low-stringency somatic variant settings. Variants were annotated using wAnnovar [14]. Called variants were filtered to prioritize likely candidate somatic drivers by removing synonymous variants, those with frequencies >0.01 in ESP6500 or 1000 genomes, those with flow corrected read depths (FDP) less than 20, flow variant allele containing reads (FAO) less than 5 or variant allele fractions (FAO/FDP) less than 0.05. Prioritized variants were compared to known somatic variants reported in TCGA sequencing data contained in the Oncomine Powertools Next Generation Sequencing database.

Copy number analysis

To identify copy number variations (CNV), normalized, GC content corrected read counts per amplicon were divided by those from a composite “normal” sample (generated from multiple individual and pooled normal FFPE samples), yielding a copy number ratio for each amplicon. Gene-level copy number estimates were determined by taking the coverage-weighted mean of the per-probe ratios, with expected error determined by the probe-to-probe variance; genes with |Z|>2 with respect to both the normal pool and the internal error were considered as gained or lost. A detailed manuscript describing this technique has been submitted (C.S.G.).

Sanger sequencing to validate called somatic variants

Ten ng of DNA were used as template in PCR amplifications with Invitrogen Platinum PCR Supermix (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Primers were designed using Primer-BLAST software (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) to produce products between 100 and 200 bp in Iength using the hg19, February 2009 human genome assembly. A universal primer (M13 sequencing primer; 5’-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT-3’) was added onto the 5’ of each forward primer. PCR products were Sanger sequenced and were analyzed using SeqMan Pro software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI).

RESULTS

Clinical and histologic features of inverted urothelial neoplasms

The mean age of patients was 69.3 years (range 49–90) with an overall M:F ratio of 3:1; all of the IUP patients were male. The anatomic distribution was skewed towards the urinary bladder (16 of 20 overall cases); notably, two cases of IUP were in the prostatic urethra and one IUP was from the renal pelvis. No IUP patient had recurrence or concurrent/subsequent UCA. Table 1 summarizes the three diagnostic categories studied, including IUP, INV-LG, and INV-HG. Two of five INV-LG had recurrences, with none demonstrating stage progression or death from disease. Five of eight INV-HG recurred, four with stage progression, and two died from disease.

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathologic features and HPV status of inverted urothelial neoplasms.

| Case # | Diagnosis | Sex | Age | Site | Recurrence | p16 IHC | HPV ISH | HPV PCRa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IUP | M | 70 | Renal Pelvis | No | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 2 | IUP | M | 55 | Bladder | No | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 3 | IUP | M | 74 | Bladder | No | Patchy | No tissueb | Negative |

| 4 | IUP | M | 64 | Prostatic urethra | Unknown | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 5 | IUP | M | 49 | Prostatic urethra | No | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 6 | IUP | M | 65 | Bladder | No | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 7 | IUP | M | 50 | Bladder | No | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 8 | INV-LG | M | 49 | Bladder | No | Focal | Negative | Negative |

| 9 | INV-LG | F | 90 | Bladder | Yes | Patchy | Negative | Negative |

| 10 | INV-LG | F | 68 | Bladder | Yes | Patchy | Negative | Negative |

| 11 | INV-LG | M | 64 | Bladder | No | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 12 | INV-LG | F | 67 | Bladder | No | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 13 | INV-HG | F | 68 | Bladder | Yes | Patchy | Negative | Negative |

| 14 | INV-HG | M | 81 | Bladder | Yes | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 15 | INV-HG | F | 70 | Renal Pelvis | No | Positive | Negative | Negative |

| 16 | INV-HG | M | 85 | Bladder | Yes | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 17c | INV-HG | M | 74 | Bladder | No | |||

| 18c | INV-HG | M | 81 | Bladder | Yes | |||

| 19c | INV-HG | M | 77 | Bladder | No | |||

| 20c | INV-HG | M | 84 | Bladder | Yes |

Abbreviations: IUP=Inverted urothelial papilloma; INV-LG= inverted papillary urothelial carcinoma, low grade, noninvasive; and INV-HG= inverted papillary urothelial carcinoma, high grade, noninvasive.

HeLa cells and cervical cancer samples (C-09T, and C-11T) were used as positive controls for HPV infection.

Case #3; No tissue remained from this scant sample for adequate in-situ hybridization analysis.

Cases #17–20; These cases of INV-HG were used for targeted next generation sequencing studies only and were not tested for HPV DNA or p16 expression.

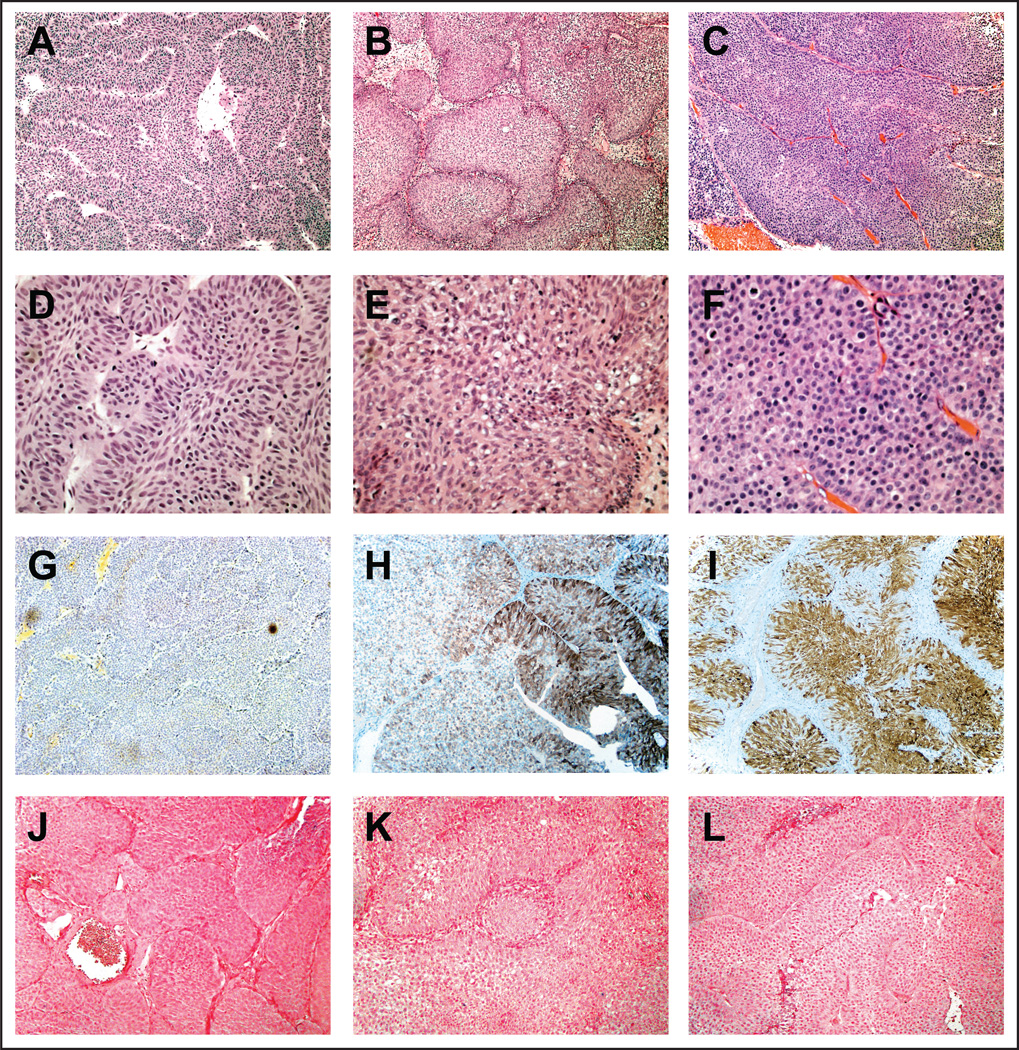

IUP are notable for their well circumscribed, inverted growth pattern composed of extensively invaginating anastomosic cords of uniform width composed of benign urothelial cells that are covered by a smooth, cytologically normal urothelial surface [11]. The cords themselves are distinguished by streaming nature of the central, urothelial cells and the palisaded basal cell located at the periphery. Focal, minor cytologicatypia may be observed by mitotic figures are rare or absent. (Figure 1A and D). INV-LG is characterized by inverted nests and clusters of neoplastic cells with an overall orderly appearance with variations in archetictural as well as cytologic features. Pleomorphism is mild with subtle variation in nuclear size and shape (Figure 1B and E). INV-LG is distinguished from IUP by the presence of expansion of the endophytic urothelial nests and more pronouncedatypia [11]. INV-HG retains the endophytic growth pattern of IUP and INV-LG, but is notable for a predominant pattern of disorder with marked disturbances in polarity, significant nuclear pleomorphism, and frequent mitotic activity above the basal layer (Figure 1C and F).

Figure 1. Inverted urothelial neoplasms do not contain HPV DNA.

(A) Low power (100×) hematoxylin and eosin stained section of an inverted papilloma demonstrating the characteristic thin, interanastomosing cords of benign cells with an inverted growth pattern. (D) High power (400×) hematoxylin and eosin stained section of the same inverted papilloma shows lack of cytologicatypia and prominent peripheral palisading. (G) Immunohistochemical staining for p16 and (J) in-situ hybridization for HPV are negative in inverted papilloma. (B and E) Low and high power (100× and 400×, respectively) views of hematoxylin and eosin stained sections of a low grade urothelial carcinoma with inverted growth pattern, demonstrating large nests of urothelium lacking high-grade cytologic features with architectural variation. (H) Patchy p16 expression by immunostaining and (K) negative HPV detection in the same low grade urothelial carcinoma with inverted growth pattern. (C and F) Low and high power (100× and 400×, respectively) views of hematoxylin and eosin stained sections of a high grade urothelial carcinoma with inverted growth pattern, demonstrating total lack of cellular polarity with marked cytologicatypia and numerous mitotic figures. (I) Positive p16 expression by immunostaining and (L) negative HPV in-situ hybridization results in the same high grade urothelial carcinoma with inverted growth pattern.

p16 expression and HPV detection by ISH

p16 immunohistochemistry is summarized in Table 1 with no IUP showing p16 positivity (representative image in Figure 1G). For INV-LG, patchy p16 expression was noted in three of five cases with variable intensity (Figure 1H). p16 was diffusely positive in two of four INV-HG cases (Figure 1I). Chromogenic ISH was performed to detect 11 high risk HPV strains, with no HPV DNA detected in any sample (Figure 1J, K, and L).

HPV detection and typing by PCR

To detect HPV at a level below the sensitivity of p16 immunohistochemistry or HPV ISH, we used PCR amplification of genomic DNA with two distinct consensus primer sets (GP5/GP6 and My09/My11) followed by direct Sanger sequencing of the PCR products. No HPV DNA was detected in any specimen (Table 1). HeLa cells and cells derived cervical cancer specimens (C-09T and C-11T) were used as positive controls for HPV infection and were positive using both primer sets (Data not shown).

Targeted next generation sequencing of inverted lesions

Five of seven IUP, all five INV-LG, and four of eight INV-HG with adequate DNA content underwent targeted next generation sequencing (NGS) using the Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot v.2 panel to assess the 50 most frequently mutated cancer genes. The mean number of mapped reads was 100,167.2 (range = 48,238 – 184,546). The mean percentage of reads on target was 93.35% (standard error of the mean (SEM) = 0.38%) and the mean uniformity of base coverage was 95.37% (SEM = 0.54%). The mean depth of base coverage for all samples was 401.5× (range = 201.2 – 766.5). Base level coverage statistics are summarized in Figure 2C.

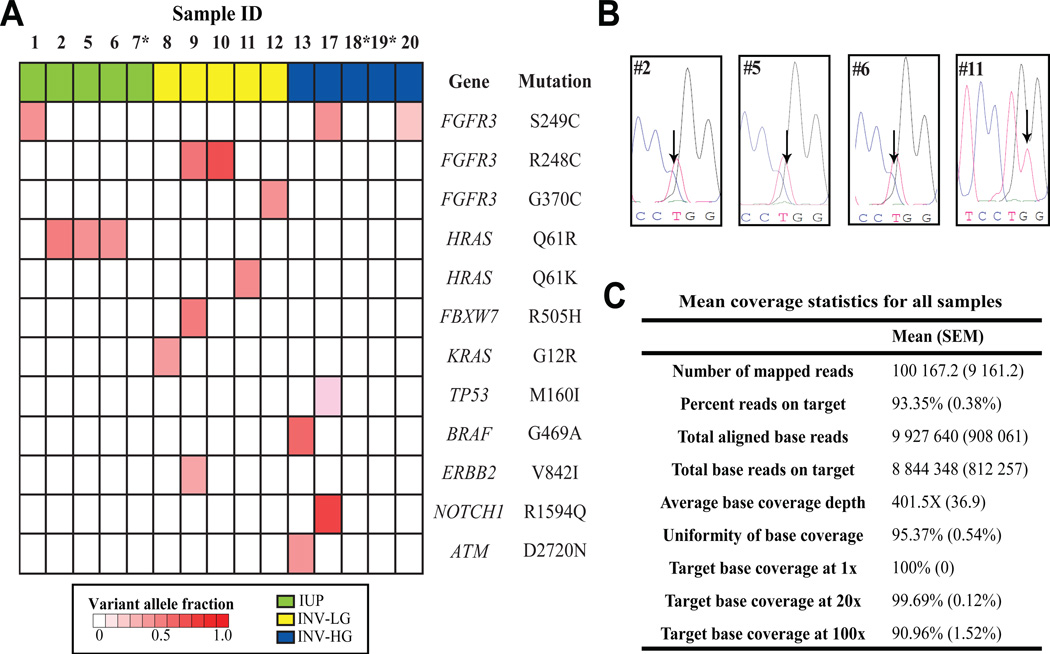

Figure 2. Summary of point mutations detected at genomic hotspots using next generation sequencing.

(A) DNA was extracted from FFPE specimens and next generation sequencing (NGS) was performed as described in the methods using the Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v.2. Called variants were filtered to prioritize likely candidate somatic drivers by removing the following variants: synonymous variants, those with frequencies greater than 0.01 in ESP6500 or 1000 genomes, those with flow corrected read depths (FDP) less than 20, flow corrected variant allele containing reads (FAO) less than 5, or variant allele fractions (FAO/FDP) less than 0.05. Green, inverted urothelial papilloma; yellow, Low grade urothelial carcinoma with inverted features; blue, high grade urothelial carcinoma with inverted features. *Samples 7, 18, and 19 contained no prioritized variants. (B) Chromatograms from confirmatory Sanger sequencing of each sample with HRAS Q61 mutations. Arrows indicate the presence of the Cytosine trace (in blue) at Chr11:533874 (reference base T, as indicated) for sample #2, 5, and 6 leading to the Q61R mutation and the presence of the Thymine trace (in red) at Chr11:533874 (reference base G, as indicated) for sample #11 leading to the Q61K mutation. (C) Summarized target base coverage data for all samples that underwent targeted NGS. Data were generated using the Coverage Analysis plugin (version 3.6.63324) on the Torrent Suite (version 3.6) software platform. SEM, Standard error of the mean

Analysis of called variants was performed after sequencing to prioritize for likely driving, somatic mutations as described in the Methods, with prioritized point mutations are summarized in Figure 2A. Three of the five IUP demonstrated identical HRAS T to C transitions leading to a Q61R amino acid substitution. One IUP contained a point mutation in FGFR3 at a location (S249C) described previously in IUP [4, 5] and in papillary UCA [15].

Additional mutations in Ras pathway members were found, including a KRAS G12R mutation in an INV-LG and a BRAF G469A mutation in an INV-HG. One additional HRAS Q61 mutation was found in an INV-LG (Q61K). Interestingly, the diagnostic report for this sample (Sample #11) noted this tumor had an unusual morphology, with focal areas of “thin cords of cells with central spindling and basilar palisading” resembling IUP; although other admixed areas were definitively INV-LG.

Other variants included FGFR3 mutations (including S249C, G370C, and R248C) in three INV-LG, and two INV-HG. One INV-LG with FGFR3 R248C carried mutations in FBXW7 and ERBB2, while one INV-HG with FGFR3 S249C also harbored mutations in NOTCH1 (R1594Q) and TP53 (M160I). While recurrent mutations in FBXW7, ERBB2, and NOTCH1 have been described in the recent bladder TCGA cohort, the specific point mutations at FBXW7 R505, ERBB2 V842, and NOTCH1 R1594 have not been previously noted in urothelial cancers [16]. Detailed information describing all prioritized variants is provided in Supplemental Table 1. Representative calls were validated via Sanger sequencing (representative traces shown in Figure 2B), confirming NGS accuracy in eight of eight samples. Three samples, including one IUP and two INV-HG, contained no prioritized mutations following NGS.

Copy number alterations derived from next generation sequencing

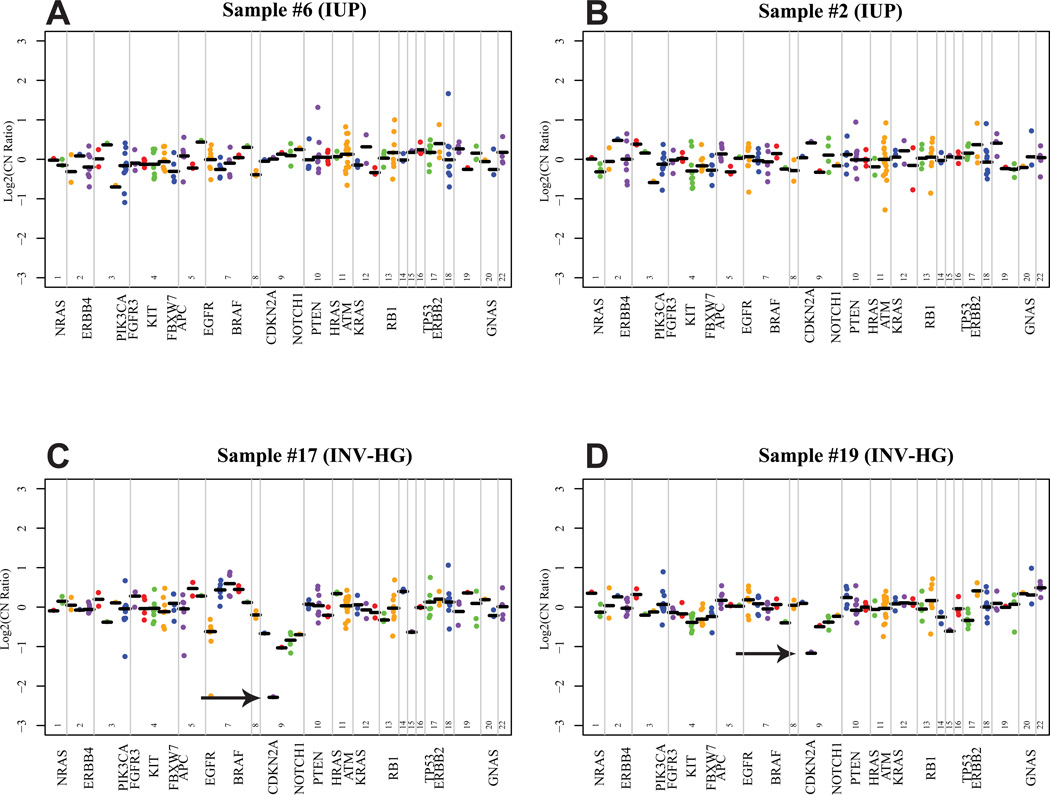

Copy number variations (CNV) via oncogene amplification or deletion of tumor suppressors can contribute to neoplasia. To determine whether CNV were present at in our NGS panel, we compared the coverage depth for individual amplicons from tumor samples to those from a composite of multiple pooled normal FFPE samples (see methods for detailed description). No significant high level CNV were found in any of the five IUP tested (Representative copy number plots shown in Figure 3A and B). The cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN2A at 9p21 is frequently deleted in UCA [17, 18] and we detected loss at CDKN2A in two INV-HG samples (Z scores= 3.413 for sample #17 and 2.384 for sample #19) (Figure 3C and D). Interestingly, one INV-HG sample with CDKN2A loss (sample number 19) contained no point variants in our panel (Figure 2).

Figure 3. Representative copy number plots derived from Ion Torrent Reads.

For each sequenced inverted urothelial neoplasm, GC content corrected, normalized read counts per amplicon were divided by those from pooled normal tissue, yielding a copy number ratio for each amplicon. Log2 copy number ratios per amplicon are plotted (with each individual amplicon represented by a single dot, and each invidual gene indicated by different colors), with gene-level copy number estimates (black bars) determined by taking the weighted mean of the per-probe copy number ratios, with expected error determined by the probe-to-probe variance. The locations of selected genes are annotated on the X-axis. For (A) and (B), Representative copy number plots from two IUP are shown with no copy number variants detected. (C) and (D) show representative plots from two INV-HG lesions with focal copy number losses at CDKN2A, with Z scores of 3.413 and 2.384, respectively (black arrows).

DISCUSSION

Since the description of IUP in 1963 [19], many have investigated the pathogenesis of this rare neoplasm. We sought to identify molecular alterations present within IUP by using NGS to investigate frequently mutated cancer “hotspots”, and here we describe for the first time the presence of recurrent HRAS Q61R substitutions in IUP. Additionally, one INV-LG also contained a HRAS Q61 mutation. HRAS acts as one of the master regulators of cell proliferation and HRAS mutations have been described in a number of studies of UCA with a frequency around 10% [16, 20, 21]. No significant correlation exists between Ras mutation status and tumor grade, stage, recurrence, progression, or survival [22].

HRAS mutations are reported to be mutually exclusive from mutations in the growth factor receptor FGFR3 [22]. FGFR3-Ras signaling is critical for early urothelial neoplasia and HRAS has been shown in mouse models to promote urothelial hyperplasia [15]. One IUP tested harbored aFGFR3 S249C mutation as previously described [4, 5]. Importantly, no IUP had mutations at other genomic hot spots nor were CNVs were detected any IUP, supporting the concept that IUP are neoplasms with a limited array of genetic aberrations. However, the fact that four of five IUP contain mutations frequently seen in UCA indicates that IUP might share some pathogenetic events with malignant disease. Nonetheless, progression and recurrence rates for IUP have been demonstrated to be very low (<2% for both) [23–25], indicating that mutations in HRAS and/or FGFR3 alone are insufficient to cause UCA. The differences between IUP and UCA with regards to their expression of Ki-67 and p53 and UroVysion FISH support this concept [6, 26].

For INV-LG and INV-HG, we found frequent FGFR3 variants (50% of cases), including known activating mutations at S249C, R248C, and G370C. Recently published genomic data on UCA published by the TCGA notes that FGFR3 mutations are enhanced in lower grade, non-invasive lesions and are strongly associated with papillary morphology [16]. The relatively high number of FGFR3 mutations in INV-HG cases seen here may be related to the fact that although they were high grade, they were non-invasive. We also noted Ras pathway mutations (HRAS, KRAS, and BRAF) in 30% of our inverted UCA, which is a higher prevalence than seen in TCGA data. The relatively high number of Ras pathway mutants in the inverted family of lesions studied here raises the possibility that disruptions of this pathway could contribute to the development of an endophytic growth pattern. Additionally, we found mutations in FBXW7, ERBB2, and NOTCH1 at amino acid locations found in other cancers but not described for UCA (R505, V842, and R1594, respectively) in recent large scale genomic analyses [16, 20, 21] and therefore the significance of these mutations as possible drivers is unclear.

Despite the difference in frequency Ras family mutations in our inverted cohort and published genome studies of UCA, it is important to note that the AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot v.2 panel used for NGS here targets the most frequently mutated genes in all cancers, and it does not provide coverage over some genomic locations known to be important for UCA. For instance, the TCGA noted that 76% of UCA have mutations in chromatin regulatory genes [16] and the Cancer Hotspot panel does not cover frequently mutated genes such as MLL2, MLL3, ARID1A, and SMARCA2. Additionally, telomere shortening is associated with inverted UCA but IUPs have normal telomere length [27]. Further, endophytic upper tract UCA frequently demonstrate microsatellite instability [28]. hTERT, TERC, and microsatellite repair genes are not included in our NGS panel, and therefore larger-scale studies of these loci in inverted neoplasms are needed in order to be able to directly compare them to exophytic UCAs.

Although our NGS panel was not designed to detect CNVs (given the limited number of amplicons in some genes), we utilized a novel method for estimating copy number status from PCR based targeted NGS data. We were able to describe CNVs, including CDKN2A loss two INV-HG lesions. Loss of chromosome 9p21 is well described in high grade UCA [17, 18, 29] and is assessed in the Urovision FISH assay. The ability to determine CNV from targeted sequencing data adds further versatility to this approach for evaluating tumors and can provide additional data about tumor biology that can be missed by deriving only substitution and indel calls from NGS data, as was seen in Sample 19 which harbored a CDKN2A deletion but no prioritized variant calls.

The possibility that IUP could be due to high risk HPV infection has been explored with conflicting results [7–10]. Here, we show that in seven cases of confirmed IUP that HPV DNA was undetectable by ISH as well as by PCR (Table 1 and Figure 1). These findings are compatible with those of Gould [10] and Alexander [9], who found no evidence of HPV infection in a combined 45 cases of IUP. Evidence has emerged showing that HPV infection is not a driving event in the carcinogenesis of UCA [30–33], except in rare circumstances like basaloid squamous cell carcinomas arising in neurogenic bladders [34] or upper tract tumors arising in kidney transplant recipients [35]. Likewise, our investigation of the HPV status of inverted UCA, both high grade and low grade, shows no presence of HPV DNA either by ISH or PCR (Table 1 and Figure 1).

In summary, we describe for the first time frequent HRAS mutations in IUP in addition to previously described FGFR3 mutations, with relatively frequent numbers of Ras pathway mutations in malignant inverted neoplasms. Despite the small number of IUP analyzed, these findings are the first evidence of HRAS mutations in this tumor and provide a clue to the pathogensis of this unique entity. Additionally, we found no evidence of involvement by HPV for the etiology of IUP or inverted UCA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This study was primarily supported by the University of Michigan Projects in Anatomic Pathology Fund (A.S.M and R.M.). This study was also supported by the A. Alfred Taubman Medical Institute (A.M.C.), the American Cancer Society (A.M.C.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (A.M.C.), and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (R.M. and A.M.C.) and National Human Genome Research Institute Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium grant 1UM1HG006508 (R.M and A.M.C.)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: There are no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Picozzi S, Casellato S, Bozzini G, et al. Inverted papilloma of the bladder: a review and an analysis of the recent literature of 365 patients. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(8):1584–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho H, Chen YD, Tan PH, Wang M, Lau WK, Cheng C. Inverted papilloma of urinary bladder: is long-term cystoscopic surveillance needed? A single center's experience. Urology. 2006;68(2):333–336. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung MT, Eble JN, Wang M, Tan PH, Lopez-Beltran A, Cheng L. Inverted papilloma of the urinary bladder: a molecular genetic appraisal. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(10):1289–1294. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eiber M, van Oers JM, Zwarthoff EC, et al. Low frequency of molecular changes and tumor recurrence in inverted papillomas of the urinary tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(6):938–946. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000249448.13466.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lott S, Wang M, Zhang S, et al. FGFR3 and TP53 mutation analysis in inverted urothelial papilloma: incidence and etiological considerations. Mod Pathol. 2009;22(5):627–632. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones TD, Zhang S, Lopez-Beltran A, et al. Urothelial carcinoma with an inverted growth pattern can be distinguished from inverted papilloma by fluorescence in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and morphologic analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(12):1861–1867. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318060cb9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan KW, Wong KY, Srivastava G. Prevalence of six types of human papillomavirus in inverted papilloma and papillary transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: an evaluation by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50(12):1018–1021. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.12.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shigehara K, Sasagawa T, Doorbar J, et al. Etiological role of human papillomavirus infection for inverted papilloma of the bladder. J Med Virol. 2011;83(2):277–285. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander RE, Davidson DD, Lopez-Beltran A, et al. Human papillomavirus is not an etiologic agent of urothelial inverted papillomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(8):1223–1228. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182863fc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gould VE, Schmitt M, Vinokurova S, et al. Human papillomavirus and p16 expression in inverted papillomas of the urinary bladder. Cancer Lett. 2010;292(2):171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eble JN World Health Organization., International Agency for Research on Cancer. Lyon, Oxford: IARC Press ;Oxford University Press (distributor); 2004. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amin MB, McKenney JK, Paner GP, et al. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Bladder Cancer 2012: Pathology. Eur Urol. 2013;63(1):16–35. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhai Y, Bommer GT, Feng Y, Wiese AB, Fearon ER, Cho KR. Loss of estrogen receptor 1 enhances cervical cancer invasion. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(2):884–895. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang X, Wang K. wANNOVAR: annotating genetic variants for personal genomes via the web. J Med Genet. 2012;49(7):433–436. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng L, Davison DD, Adams J, et al. Biomarkers in bladder cancer: translational and clinical implications. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2014;89(1):73–111. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature. 2014;507(7492):315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orlow I, Lacombe L, Hannon GJ, et al. Deletion of the p16 and p15 genes in human bladder tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(20):1524–1529. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.20.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson MP, Elder PA, Shaw ME, Devlin J, Knowles MA. p16 (CDKN2) is a major deletion target at 9p21 in bladder cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4(9):1569–1577. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.9.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potts IF, Hirst E. Inverted Papilloma of the Bladder. J Urol. 1963;90:175–179. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)64384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balbas-Martinez C, Sagrera A, Carrillo-de-Santa-Pau E, et al. Recurrent inactivation of STAG2 in bladder cancer is not associated with aneuploidy. Nature genetics. 2013;45(12):1464–1469. doi: 10.1038/ng.2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo G, Sun X, Chen C, et al. Whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing of bladder cancer identifies frequent alterations in genes involved in sister chromatid cohesion and segregation. Nature genetics. 2013;45(12):1459–1463. doi: 10.1038/ng.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouerhani S, Elgaaied AB. The mutational spectrum of HRAS, KRAS, NRAS and FGFR3 genes in bladder cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2011;10(6):259–266. doi: 10.3233/CBM-2012-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown AL, Cohen RJ. Inverted papilloma of the urinary tract. BJU international. 2011;107(Suppl 3):24–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montironi R, Cheng L, Lopez-Beltran A, et al. Inverted (endophytic) noninvasive lesions and neoplasms of the urothelium: the Cinderella group has yet to be fully exploited. Eur Urol. 2011;59(2):225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sung MT, Maclennan GT, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Cheng L. Natural history of urothelial inverted papilloma. Cancer. 2006;107(11):2622–2627. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheville JC, Wu K, Sebo TJ, et al. Inverted urothelial papilloma: is ploidy, MIB-1 proliferative activity, or p53 protein accumulation predictive of urothelial carcinoma? Cancer. 2000;88(3):632–636. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<632::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williamson SR, Zhang S, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Wang M, Cheng L. Telomere shortening distinguishes inverted urothelial neoplasms. Histopathology. 2013;62(4):595–601. doi: 10.1111/his.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartmann A, Dietmaier W, Hofstadter F, Burgart LJ, Cheville JC, Blaszyk H. Urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: inverted growth pattern is predictive of microsatellite instability. Hum Pathol. 2003;34(3):222–227. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orlow I, LaRue H, Osman I, et al. Deletions of the INK4A gene in superficial bladder tumors. Association with recurrence. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65105-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexander RE, Hu Y, Kum JB, et al. p16 expression is not associated with human papillomavirus in urinary bladder squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(11):1526–1533. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polesel J, Gheit T, Talamini R, et al. Urinary human polyomavirus and papillomavirus infection and bladder cancer risk. British journal of cancer. 2012;106(1):222–226. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westenend PJ, Stoop JA, Hendriks JG. Human papillomaviruses 6/11, 16/18 and 31/33/51 are not associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. BJU Int. 2001;88(3):198–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yavuzer D, Karadayi N, Salepci T, Baloglu H, Bilici A, Sakirahmet D. Role of human papillomavirus in the development of urothelial carcinoma. Medical oncology. 2011;28(3):919–923. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blochin EB, Park KJ, Tickoo SK, Reuter VE, Al-Ahmadie H. Urothelial carcinoma with prominent squamous differentiation in the setting of neurogenic bladder: role of human papillomavirus infection. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2012;25(11):1534–1542. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Husain E, Prowse DM, Ktori E, et al. Human papillomavirus is detected in transitional cell carcinoma arising in renal transplant recipients. Pathology. 2009;41(3):245–247. doi: 10.1080/00313020902756303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.