Abstract

This research examined an integration of cognitive and interpersonal theories of depression by investigating the prospective contribution of depressive rumination to perceptions of social support, the generation of interpersonal stress, and depressive symptoms. It was hypothesized that depressive ruminators would generate stress in their relationships, and that social support discontent would account for this association. Further, depressive rumination and dependent interpersonal stress were examined as joint and unique predictors of depressive symptoms over time. Participants included 122 undergraduate students (M age = 19.78 years, SD = 3.54) who completed assessments of depressive rumination, perceptions of social support, life stress, and depressive symptoms across three waves, each spaced 9 months apart. Results revealed that social support discontent accounted for the prospective association between depressive rumination and dependent interpersonal stress, and that both depressive rumination and dependent interpersonal stress contributed to elevations in depressive symptoms over time. These findings highlight the complex interplay between cognitive and interpersonal processes that confer vulnerability to depression, and have implications for the development of integrated depression-focused intervention endeavors.

Keywords: Rumination, Social support, Interpersonal stress, Depression

Introduction

Research examining both cognitive (e.g., Abramson et al. 1989; Beck 1967; Nolen-Hoeksema 1991) and interpersonal stress generation (e.g., Coyne 1976; Hammen 1991, 1992, 2006; Joiner and Coyne 1999) theories of depression provides a wealth of evidence that individuals vulnerable to depression have a tendency to both ruminate over negative affective states, as well as to create conflict and disturbances in their interpersonal relationships. The goal of this research was to attempt to integrate these theories and examine how depressive ruminators generate interpersonal stress. Specifically, perceptions of social support were examined as a causal mechanism through which depressive rumination contributes to relationship disturbances. Further, the joint and unique contributions of depressive rumination and dependent interpersonal stress to depressive symptoms were examined over time.

Intra- and Interpersonal Consequences of Depressive Rumination

Depressive rumination, defined as the tendency to passively and repetitively focus on the experience of negative moods, as well as their causes and consequences, is a widely established risk factor for emotional and psychological maladjustment (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991; Spasojevic and Alloy 2001; Weinstock and Whisman 2007), and depressive episodes in particular (Just and Alloy 1997; Nolen-Hoeksema 2000; Spasojevic and Alloy 2001). For instance, findings from experimental studies indicate that rumination leads to more negative, biased interpretations of life events (Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema 1995), facilitates recall of negative autobiographical memories and events (Lyubomirsky et al. 1998), and reduces willingness to participate in pleasant activities (Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema 1993). Thus, by keeping attention focused on negative content, depressive ruminators appear to perpetuate the experience of negative affect and heighten vulnerability to intrapersonal impairment (for reviews see Alloy et al. 2006a, b; Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008; Spasojevic et al. 2003).

Despite the frequent documentation of associations between depressive rumination and intrapersonal functioning, less research has examined associations between depressive rumination and interpersonal functioning. The interpersonal stress generation theory of depression (Coyne 1976; Hammen 1991, 1992, 2006; Joiner and Coyne 1999) posits that characteristics of depressed and depression-prone individuals create stress in interpersonal relationships. Although the origination of this theory focused on the interpersonal dysfunction generated by depressed individuals, more contemporary theory (e.g., Hammen 2006) and a growing body of empirical research indicate that characteristics of depression-prone individuals (i.e., individuals with underlying cognitive, emotional, and/or interpersonal vulnerabilities to depression) also elicit relationship disturbances. Specifically, depressed and depression-prone individuals generate interpersonal stress via mechanisms including excessive reassurance-seeking (Potthoff et al. 1995; Prinstein et al. 2005), insecure attachment orientation (Bottonari et al. 2007; Hankin et al. 2005), personality and cognitive style characteristics (Daley et al. 2006, 1997; Safford et al. 2007; Shih 2006), maladaptive interpersonal stress responses (Flynn and Rudolph 2008), and ineffective interpersonal problem solving (Davila et al. 1995). Moreover, individuals who ruminate display a range of dysregulated behaviors (e.g., impulsivity, consuming alcohol to cope; Selby et al. 2008), which likely compromise interpersonal functioning and contribute to interpersonal impairment. Guided by these converging lines of research, the first goal of this study was to examine whether depressive rumination, an established characteristic of depressed and depression-prone individuals, generates prospective elevations in interpersonal stress.

Several mechanisms may explain how depressive rumination creates relationship disturbances. For instance, the concomitant stress associated with dwelling on negative affective states might distress depressive ruminators and predispose them to create interpersonal conflict. Similarly, depressive ruminators might behave in a hopeless, apathetic, or pessimistic fashion which might irritate other people and elicit interpersonal rejection. Alternatively, the chronic experience of negative cognitions and emotions might be so overwhelming that depressive ruminators withdraw from relationships and become interpersonally isolated. Overall, this detrimental self-perpetuating process of depressive rumination is likely to lead to a depletion of protective interpersonal factors that accompany supportive and nurturing relationships, and to generate a diverse array of interpersonal disturbances.

Theory (Joiner 2000) and preliminary concurrent research (Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema 1995; Weinstock and Whisman 2007) indicate that depressive rumination contributes to interpersonal impairment. In one study, depressive rumination hindered interpersonal problem-solving (Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema 1995). Specifically, dysphoric ruminators generated responses to hypothetical interpersonal problems that were objectively less effective at problem resolution, as well as fewer strategies that were deemed to be interpersonally adaptive (Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema 1995). Results from a second study revealed an association between depressive rumination and excessive reassurance-seeking, a widely established maladaptive interpersonal behavior, in a sample of undergraduate students (Weinstock and Whisman 2007). Building on these findings, the second goal of this study was to investigate how depressive rumination might contribute to self-generated interpersonal stress, and examined perceptions of social support as a mechanism accounting for this link.

Perceptions of Social Support

Strong social support networks are a commonly accepted protective factor for emotional, cognitive, and behavioral adjustment (for reviews, see Pennebaker 1989, 1993). Individual differences in depressive rumination may contribute to the nature and amount of social support that is sought, as well as perceptions of social support, broadly speaking (e.g., perceived need for social support, satisfaction with social support). Specifically, the tendency to experience and dwell on negative cognitions and moods might cause individuals to perceive themselves as needing more social support in order to manage their intrapersonal distress. Indeed, two studies reveal significant associations between rumination and perceptions of insufficient social support resources (Abela et al. 2004; Adams et al. 2007). Similarly, depressive ruminators report seeking more, but receiving less, social support over time (Nolen-Hoeksema and Davis 1999). In turn, the experience of seeking more but receiving less social support likely predisposes individuals to become dissatisfied with their social support networks. Furthermore, if the social support that is received does not alleviate the distress invoked by depressive rumination, perceived satisfaction with social support might diminish. However, an increased need of social support may not lead to overall discontent when individuals are satisfied with the support that is provided by others, and it may be the joint and detrimental combination of perceiving an insufficient amount and inadequate quality of social support that predisposes depressive ruminators to become discontented with their social support resources.

In turn, social support resources discontent might lead depressive ruminators to create relationship disturbances. Specifically, depressive ruminators might generate interpersonal tension or conflict by persisting in social support seeking for longer periods of time than those sanctioned by social norms. Depressive ruminators might also behave in inappropriate ways to obtain additional social support and, consequently, burden members of their social support network. As an alternative, depressive ruminators might provide feedback that the social support offered to them is deficient or unsatisfactory and, in turn, estrange their interpersonal environments. Ultimately, each of these maladaptive interpersonal behaviors is likely to compromise social support resources and create stressful relationship disturbances. Thus, social support discontent was examined as a mediator of the association between depressive rumination and interpersonal stress generation.

Interpersonal Stress Generation and Depressive Symptoms

The final goal of this study was to examine whether self-generated interpersonal stress contributes to the development of depressive symptoms over time. Beyond the concomitant disruption of social support, individuals who generate interpersonal stress also forgo provisions fostered through nurturing relationships, such as the mastery of emotional and behavioral self-regulation and the attainment of security and external validation (Rudolph 2002). Jointly, the loss of interpersonal support and the creation of interpersonal stress may lead individuals to feel socially incompetent, to doubt their self-worth, and to acquire a diminished sense of self-efficacy. As a consequence, individuals with pervasive relationship disruptions likely experience heightened levels of negative affect, feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness, and other symptoms of depression. Consistent with this notion, research demonstrates that the experience of family, peer, and romantic stress predicts the development of depressive symptoms (for a review, see Rudolph et al. 2007). Further, some research indicates that interpersonal stress generation accounts for associations between characteristics of depression-prone individuals and elevations in depressive symptoms (Hankin et al. 2005; Shih 2006). Accordingly, this research aimed to both replicate the finding that the generation of interpersonal stress prospectively predicts depressive symptoms, and to explore whether the generation of interpersonal stress accounted for the prospective association between depressive rumination and depressive symptoms.

Overview of the Current Study

This study is the first to examine interpersonal consequences of depressive rumination in a sample of initially non-depressed individuals who were followed prospectively for approximately 18 months. We hypothesized that depressive rumination would contribute to the generation of interpersonal stress, and that social support discontent would account for this association. We further hypothesized that self-generated interpersonal stress would prospectively contribute to depressive symptoms, and examined whether dependent interpersonal stress accounted for the association between depressive rumination and depressive symptoms. Finally, we investigated whether this process model was specific to the experience of stressful dependent interpersonal, and not dependent achievement or independent, life events.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were a subset of those selected for inclusion at the Temple University (TU) site of the Temple-Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression (CVD) Project (Alloy and Abramson 1999). The selection process and the characteristics and representativeness of CVD Project participants have been described in detail in previous publications (e.g., Alloy and Abramson 1999; Alloy et al. 2000, 2006a, b). Consequently, only a brief summary of the procedures and the sample characteristics will be provided.

Participants were selected by first screening a large sample of college freshmen with the Cognitive Style Questionnaire (CSQ; Alloy et al. 2000; Haeffel et al. 2008) and the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS; Weisman and Beck 1978) to determine cognitive vulnerability to depression. High risk status was assigned to individuals scoring in the highest (most negative) quartile on both the CSQ negative events composite and the DAS, and low risk status was assigned to individuals scoring in the lowest (most positive) quartile on both the CSQ negative event composite and the DAS.1 In the second phase of the screening process, a modified Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime (Endicott and Spitzer 1978) diagnostic interview was administered to a randomly selected subsample of the high and low risk individuals. A final eligible sample was identified based on several exclusionary criteria (i.e., diagnosis of a current or past affective or Axis I psychiatric disorder, or serious medical illness).

The CVD Project participants who completed the Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ; Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991) at the initial assessment at TU (only TU participants completed the RSQ) were included in the current study. Of the 122 participants (M age = 19.78 - years, SD = 3.54), 75 were female and 47 were male; 64 were high risk status and 58 were low risk status. The sample was diverse in terms of ethnicity (63% White, 27% African-American, 10% other). The subsample of participants included in the present study was comparable to the complete sample in terms of gender, age, ethnicity, cognitive risk status, and initial depressive symptoms. High and low risk participants in this subsample did not differ from one another on any demographic characteristics.

Procedure

Participants completed assessments at three primary waves (W1, W2, and W3) spaced approximately 9 months apart. First, participants completed a measure of depressive rumination at W1. Next, perceptions of social support were assessed at three evenly spaced 3-month intervals between W1 and W2 in order to obtain an index of W1–2 perceptions of social support. Finally, life stress was assessed at W1 and W2, and depressive symptoms were assessed at W1 and W3. To minimize attrition, assessments were conducted by phone and mail when participants were unable to attend laboratory sessions. Participants were compensated monetarily.

Measures

Depressive Rumination

The Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ; Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991) was used to assess how participants tend to respond to depressive moods. The Ruminative Responses subscale consists of 22 items assessing responses to depressed moods that are self-focused (e.g., “Isolate myself and think about the reasons I feel sad”), symptom focused (e.g., “Think about how sad I feel”), or focused on possible causes and consequences of the depressive mood (e.g., “Think ‘I won’t be able to do my job/work because I feel so badly’”). Items were rated on a 4-point scale (Almost Never, Sometimes, Often, or Almost Always); responses were summed such that higher scores reflect a greater tendency to depressively ruminate. Previous research has established that the Ruminative Responses subscale of the RSQ has good internal consistency (α = .89; Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991), five-month retest reliability (r = .80; Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1994), and validity for prospectively predicting depression (e.g., Just and Alloy 1997; Nolen-Hoeksema 2000; Spasojevic and Alloy 2001). In the present sample, internal consistency of the depressive rumination subscale was strong (α = .92).

Social Support Perceptions

The Social Support Inventory (SSI; Brown et al. 1988, 1987; Multon and Brown 1987) was used to measure (1) the amount of needed social support and (2) satisfaction with received social support. The measure consists of 39 items tapping a wide range of social support, specifically: (a) acceptance and belonging needs (i.e., information that one is loved, valued, and respected); (b) expressive needs (i.e., encouragement to express thoughts and emotions); (c) guidance needs (i.e., assistance in problem solving and decision making); and (d) utilitarian needs (i.e., provision of goods and services to deal with life circumstances). Sample items include “Assurance that you are loved and cared about,” “Help and assistance in setting realistic goals for yourself,” and “Knowledge that others are comfortable and willing to talk about anything with you.” Participants rate on a scale from 1 (None/Not Satisfied) to 7 (Very Much/Very Satisfied) the extent to which they needed and were satisfied with each perception. Ratings were averaged across the 3 assessments in the 9-month interval between W1 and W2 to compute “needed” and “satisfaction” subscales; higher scores reflect higher perceptions of needed social support and satisfaction with social support.

The SSI has demonstrated strong internal consistency, as well as both concurrent and construct validity (Brown et al. 1988; Multon and Brown 1987). The alpha coefficients for the SSI subscales in the present sample were excellent at the first administration of the measure (needed α = .98; satisfaction α = .99). In addition, the individual subscales of the measure demonstrated respectable average levels of retest reliability (needed r = .77; satisfaction r = .60). To examine our specific study hypotheses, a composite score representing social support discontent was computed. Specifically, satisfaction with social support was subtracted from needed social support such that higher scores reflect greater discontentment with social support.

Life Stress

The Life Events Scale (LES; Alloy and Clements 1992; Needles and Abramson 1990; Safford et al. 2007) is a life event inventory that includes a diverse and comprehensive array of 102 interpersonal and achievement life events. Events included both major and minor events; in order for minor events to meet definitional criteria they had to have been recurrent. Sample interpersonal events include “Close friend moved away,” “Frequent fights or disagreements with one or more family members,” and “Cheated on by romantic partner.”2 Sample achievement events include “Failed an exam or major project in an important course,” “Were not accepted into a major or college of choice,” and “Laid off or fired from job.” After completing the LES, participants were interviewed by a trained research assistant who was blind to scores on other study variables on the Stress Interview (SI). The SI provided for the precise definition of events in an attempt to minimize bias due to subjective report. Specifically, the SI included standardized probes and specific criteria for event definition, and events that did not meet criteria were disqualified by the interviewer.

LES events were a priori categorized by the project investigators as interpersonal or achievement in nature. In addition, events were rated by independent raters (two clinical psychologists and one advanced clinical doctoral student) with regard to how much influence the participant was likely to have had over the occurrence of the event (i.e., dependence ratings). All events were rated on a scale from 0 (Completely Independent) to 3 (Completely Dependent). A final dependence rating was obtained by calculating the mean score across the three raters; inter-rater reliability was excellent (α = .95). Events with a mean dependence score of 2 and above were classified as dependent events. Events were then classified into the following four categories: dependent interpersonal, independent interpersonal, dependent achievement, and independent achievement. The number of events falling into each category was summed such that higher scores reflect the experience of a greater number of events falling within each domain.

The LES demonstrates strong inter-rater reliability (r = .89; Alloy and Abramson 1999). Additionally, the SI has demonstrated validity in terms of its ability to comprehensively capture life events over time (Safford et al. 2007). For instance, findings from a pilot study indicated a 100% recall of the events participants had experienced over the course of a month, and the events were correctly dated with 92% accuracy (Alloy and Abramson 1999).

Depressive Symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al. 1979) is a widely used index of depressive symptoms. The BDI contains 21 items that participants rate on a scale from 0 (no endorsement of the symptom) to 3 (complete endorsement of the symptom). Ratings are summed across items to compute a total score; higher scores reflect higher levels of depressive symptoms. The validity and reliability of the BDI have been established (e.g., Beck et al. 1988). Strong internal consistency was found in the present sample (αs = .91).

Results

Overview of Analytic Approach

First, zero-order correlations were computed to examine the general pattern of associations among key study variables. Next, a series of path analyses was conducted with structural equation modeling to examine study hypotheses over time. The error terms among the W1 exogenous variables were allowed to correlate freely. All analyses predicting life stress and depressive symptoms adjusted for W1 life stress and W1 depressive symptoms, respectively, in order to investigate residual changes in these variables over time.

Correlational Analyses

Table 1 displays the descriptive information and intercorrelations among the variables. W1 depressive rumination was significantly positively associated with W1–2 social support discontent, W2 dependent interpersonal stress, W2 dependent achievement stress, and W3 depressive symptoms. W1–2 social support discontent was significantly positively associated with W2 dependent interpersonal stress, and W3 depressive symptoms. W2 dependent interpersonal stress was significantly positively associated with W3 depressive symptoms, and W2 dependent achievement stress was significantly positively associated with both W2 independent achievement stress and W3 depressive symptoms. W2 independent achievement stress was significantly positively associated with W3 depressive symptoms; W2 independent interpersonal stress was not associated with any study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive information and intercorrelations among the variables

| Measure | Range | M | (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. W1 depressive rumination | 0–49.00 | 14.02 | 10.20 | – | ||||||

| 2. W1–2 social support discontent | −234 to 143.33 | −98.79 | 89.85 | .40** | – | |||||

| 3. W2 dependent interpersonal stress | 0–5.00 | 1.15 | 1.20 | .18* | .29** | – | ||||

| 4. W2 independent interpersonal stress | 0–2.00 | .46 | .63 | .08 | −.04 | .01 | – | |||

| 5. W2 dependent achievement stress | 0–10.00 | 1.10 | 1.66 | .25** | .16 | .11 | −.01 | – | ||

| 6. W2 independent achievement stress | 0–7.00 | .93 | 1.28 | .11 | .01 | .14 | .07 | .49** | – | |

| 7. W3 depressive symptoms | 0–34.67 | 5.60 | 13.75 | .37** | .19* | .38** | .12 | .24* | .21* | – |

P < .05.

P < .01

Role of Dependent Interpersonal Stress

Examination of Mediation by Social Support Discontent

Based on the observed positive and significant associations among W1 depressive rumination, W1–2 social support discontent, and W2 dependent interpersonal stress, path analyses were conducted to examine whether W1–2 social support discontent mediated the association between W1 depressive rumination and W2 dependent interpersonal stress, controlling for W1 dependent interpersonal stress. Following the guidelines recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986), three criteria must be met to establish mediation: (1) the independent variable must predict the mediator, (2) the mediator must predict the dependent variable after including the independent variable in the model, and (3) the association between the independent variable and the dependent variable should be reduced to nonsignificance after including the mediator in the model.

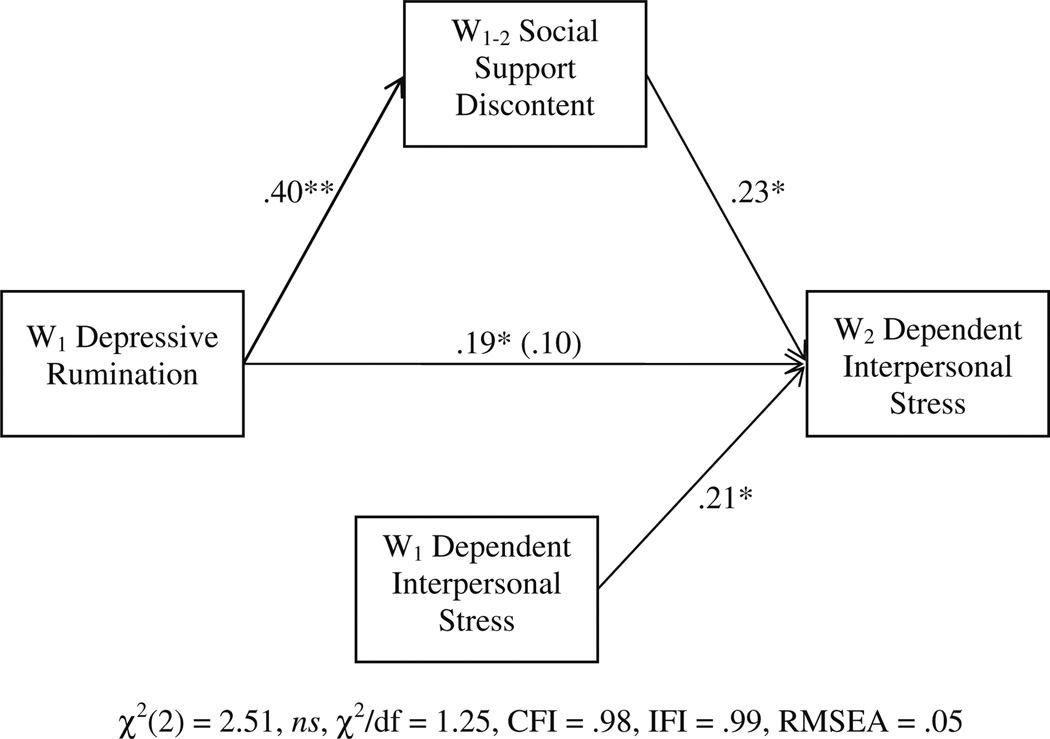

To test mediation, a model was created that included the path from W1 depressive rumination to W2 dependent interpersonal stress, the path from W1 depressive rumination to W1–2 social support discontent, the path from W1–2 social support discontent to W2 dependent interpersonal stress, and the stability path from W1 to W2 dependent interpersonal stress (see Fig. 1). As anticipated, W1 depressive rumination significantly predicted W1–2 social support discontent, and W1–2 social support discontent significantly predicted the residual change in dependent interpersonal stress (i.e., W2 adjusting for W1). In addition, the total effect of W1 depressive rumination on W2 dependent interpersonal stress reduced to nonsignificance when W1–2 social support discontent was included in the model. Consistent with mediation, the model including the direct effect between W1 depressive rumination and W2 dependent interpersonal stress did not provide a significantly better fit than the model without the direct effect, Δχ2(1) = .91, ns, and the indirect effect of W1 depressive rumination on W2 dependent interpersonal stress was significant (IE = .09, Z = 2.54, P = .01; Sobel 1982, 1986). Finally, the effect proportion (indirect effect/total effect; Shrout and Bolger 2002) indicated that 47% of the total effect of W1 depressive rumination on W2 dependent interpersonal stress was accounted for by W1–2 social support discontent. Overall, these findings indicate that W1–2 social support discontent mediated the association between W1 depressive rumination and W2 dependent interpersonal stress, controlling for W1 dependent interpersonal stress.

Fig. 1.

Path model of the associations among W1 depressive rumination, W1–2 social support discontent, and W2 dependent interpersonal stress, adjusting for W1 dependent interpersonal stress. Coefficients without parentheses indicate total effects; the coefficient in parentheses indicates the direct effect. * P < .05. ** P < .01

Examination of Mediation by Dependent Interpersonal Stress

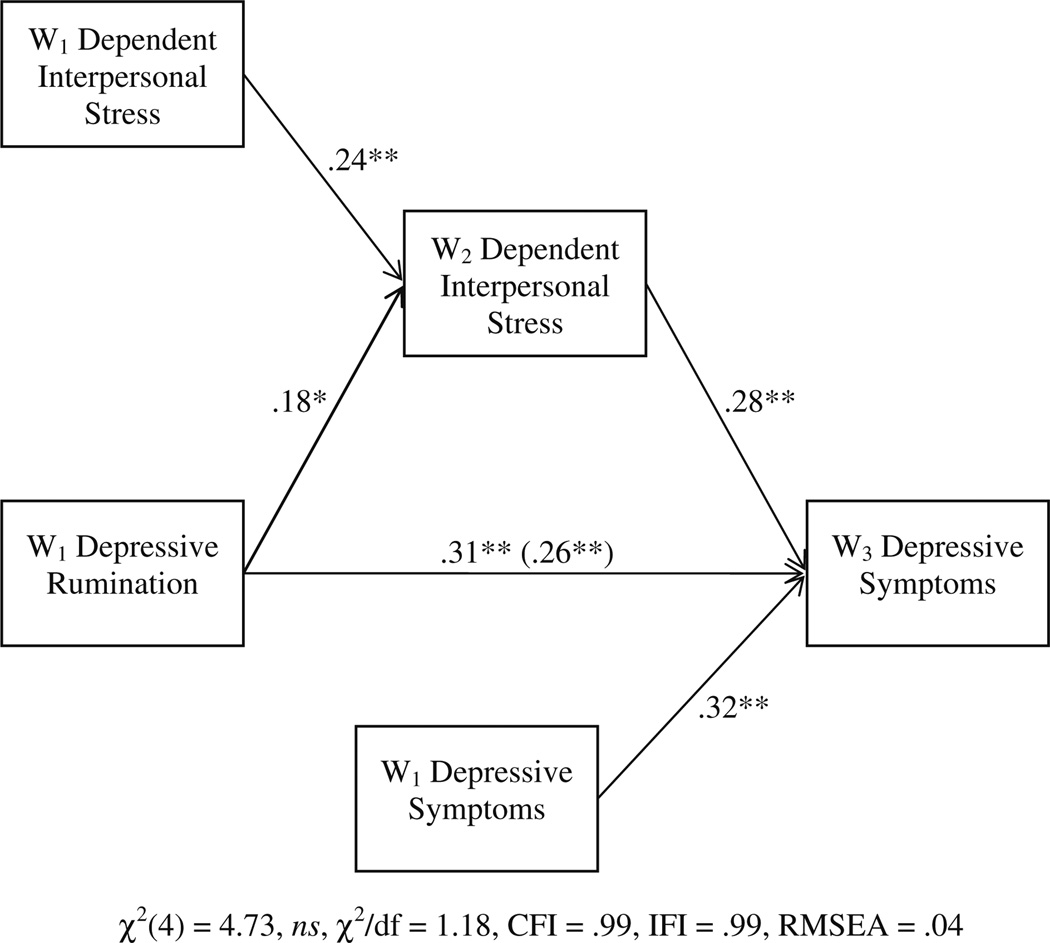

Based on the observed positive and significant associations among W1 depressive rumination, W2 dependent interpersonal stress, and W3 depressive symptoms, path analyses were conducted to examine whether W2 dependent interpersonal stress mediated the association between W1 depressive rumination and W3 depressive symptoms, controlling for W1 dependent interpersonal stress and W1 depressive symptoms. A model was created that included the path from W1 depressive rumination to W3 depressive symptoms, the path from W1 depressive rumination to W2 dependent interpersonal stress, and the path from W2 dependent interpersonal stress to W3 depressive symptoms; the stability paths from W1 to W2 dependent interpersonal stress and from W1 to W3 depressive symptoms were also included in the model (see Fig. 2). As anticipated, W1 depressive rumination significantly predicted W2 dependent interpersonal stress, and W2 dependent interpersonal stress significantly predicted W3 depressive symptoms. However, although the total effect of W1 depressive rumination on W3 depressive symptoms was reduced when W2 dependent interpersonal stress was included in the model, the path remained significant. Also inconsistent with mediation, the model including the direct effect between W1 depressive rumination and W3 depressive symptoms provided a significantly better fit than the model without the direct effect, Δχ2(1) = 7.34, P <.01, and the indirect effect of W1 depressive rumination on W2 dependent interpersonal stress was not significant (IE = .05, Z = 1.65, ns; Sobel 1982, 1986). Finally, the effect proportion (indirect effect/total effect; Shrout and Bolger 2002) indicated that only 17% of the total effect of W1 depressive rumination on W3 depressive symptoms was accounted for by W2 dependent interpersonal stress. Overall, these findings indicate that W2 dependent interpersonal stress did not mediate the association between W1 depressive rumination and W3 depressive symptoms, controlling for W1 dependent interpersonal stress and W1 depressive symptoms. However, both W1 depressive rumination and W2 dependent interpersonal stress made significant unique independent contributions to W3 depressive symptoms.

Fig. 2.

Path model of the associations among W1 depressive rumination, W2 dependent interpersonal stress, and W3 depressive symptoms, adjusting for W1 dependent interpersonal stress and W1 depressive symptoms. Coefficients without parentheses indicate total effects; the coefficient in parentheses indicates the direct effect. * P < .05. ** P < .01

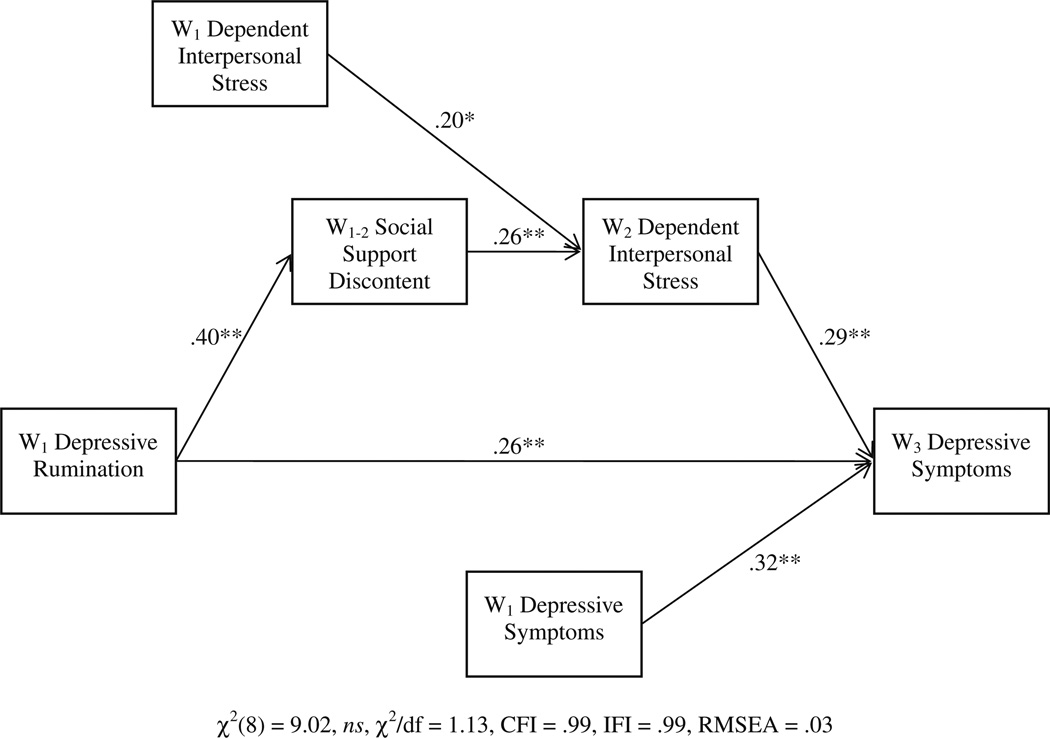

Examination of the Comprehensive Model

Based on the obtained significant results, a final path analysis was conducted to examine the fit of the comprehensive model. Specifically, a model was created that included the path from W1 depressive rumination to W3 depressive symptoms, the path from W1 depressive rumination to W1–2 social support discontent, the path from W1–2 social support discontent to W2 dependent interpersonal stress, and the path from W2 dependent interpersonal stress to W3 depressive symptoms; the stability paths from W1 to W2 dependent interpersonal stress and from W1 to W3 depressive symptoms were also included in the model (see Fig. 3). Results revealed that this model provided an excellent fit to the data, and all of the paths included in the model remained significant.

Fig. 3.

Comprehensive path model of the associations among W1 depressive rumination, W1–2 social support discontent, W2 dependent interpersonal stress, and W3 depressive symptoms, adjusting for W1 dependent interpersonal stress and W1 depressive symptoms. * P < .05. ** P < .01

Role of Dependent Achievement Stress

First, the pattern of correlations revealed that W1 depressive rumination was associated with W2 dependent achievement stress. However, W1–2 social support discontent was not associated with W2 dependent achievement stress, thereby precluding examination of social support discontent as a mediator of the association between W1 depressive rumination and W2 dependent achievement stress. Second, the pattern of correlations revealed that W2 dependent achievement stress was significantly positively associated with W1 depressive rumination and W3 depressive symptoms. Thus, to examine whether W2 dependent achievement stress accounted for the association between W1 depressive rumination and W3 depressive symptoms, a model was created that included the path from W1 depressive rumination to W3 depressive symptoms, the path from W1 depressive rumination to W2 dependent achievement stress, and the path from W2 dependent achievement stress to W3 depressive symptoms; the stability paths from W1 to W2 dependent achievement stress and from W1 to W3 depressive symptoms were also included. Although W1 depressive rumination significantly predicted W2 dependent achievement stress, W2 dependent achievement stress did not predict subsequent depressive symptoms (β = −.02, ns), and examination of mediation was consequently discontinued.

Discussion

This study examined an integration of cognitive and interpersonal theories of depression by investigating whether and how depressive ruminators create disturbances in their interpersonal relationships; both depressive rumination and subsequent dependent interpersonal stress were then tested as joint and unique prospective predictors of depressive symptoms. Consistent with hypotheses, depressive rumination predicted elevations in dependent interpersonal stress over time, and social support discontent accounted for this association. Further, both depressive rumination and self-generated interpersonal stress predicted the development of depressive symptoms, although dependent interpersonal stress did not account for the association between depressive rumination and depressive symptoms over time. These findings reveal an integrative process model through which depressive rumination indirectly created relationship disturbances; the intrapersonal experience of depressive rumination and the interpersonal experience of self-generated stress then made independent contributions to the development of depressive symptoms.

This study was novel in its examination of depressive rumination as a predictor of perceptions of social support and interpersonal stress generation. As anticipated, depressive rumination predicted heightened perceptions of social support discontent (i.e., increased levels of needed social support and decreased levels of satisfaction with social support). The tendency to repetitively, yet passively, dwell on negative moods, as well as their causes and consequences, by its very nature evokes and maintains psychological and emotional distress. Chronic and pervasive distress, in turn, might lead individuals to perceive themselves as needing a greater amount of advice or assistance from others in order to alleviate their troubles because they cannot themselves relieve their internal disturbances. If, however, an increased amount of social support is not available (e.g., there is an insufficient number of people to consult, existing relationships are not suitably intimate for the disclosure of such private information), depressive ruminators might become dissatisfied with their network of social support. Alternatively, if an increased amount of social support is available but does not successfully interrupt the cycle of emotional distress and negative self-perceptions evoked by the ruminative process, depressive ruminators might also experience a diminution in satisfaction with social support. Consistent with these ideas, rumination is associated with perceptions of inadequate social support resources (Abela et al. 2004; Adams et al. 2007).

Either way, the discontent associated with the joint experience of needing more and feeling less satisfied with social support might generate an array of relationship disturbances. For instance, social support discontent might predispose depressive ruminators to seek social support in an inappropriate or unconventional fashion (e.g., excessive reassurance seeking; Weinstock and Whisman 2007) and thereby create conflict or tension in their relationships. In addition, social support discontent might contribute to expressions of pessimism or gloom during interpersonal interactions (for associations between negative cognitive style and perceptions of social support, see Adams et al. 2007), which is likely to be distasteful or irritating to others. On the other hand, social support discontent might serve as yet another concern on which to dwell; the resulting increase in negative cognition and affect might overwhelm depressive ruminators and cause them to withdraw or disengage from interpersonal interactions. Overall, a variety of viable mechanisms might explain links between depressive rumination, social support discontent, and the generation of relationship disturbances. One goal of future research will be to explore potential moderators and mediators of the associations between rumination, perceptions of social support and interpersonal functioning.

Role of Life Stress

A guiding premise of this research was that depressive rumination and subsequent depressive symptoms would specifically be associated with dependent interpersonal, and not dependent achievement or independent life events. Although this hypothesis generally held, one interesting and unanticipated finding emerged. Specifically, depressive rumination also made a prospective contribution to self-generated achievement stress, suggesting that the tendency to dwell on negative moods not only disturbs interpersonal functioning, but also disrupts performance in academic and employment contexts. It is plausible the negative self-focus associated with depressive rumination distracts individuals while in class or at work, such that they are unable to devote their attention to achievement-related activities. In turn, although W2 dependent achievement stress and W3 depressive symptoms were significantly positively correlated, W2 dependent achievement stress did not predict elevations in depressive symptoms over time. This finding is consistent with one previous study in which dependent interpersonal, but not dependent noninterpersonal, life stress prospectively predicted depressive symptoms in girls (Rudolph et al. 2009). The experience of dependent interpersonal stress may influence self-perceptions more robustly than dependent achievement stress, such that relationship disturbances create more negative self-appraisals than self-generated achievement stressors and, consequently, are a more robust predictor of depressive symptoms.

In addition, this study design provided the opportunity to examine a specific component of the interpersonal stress generation theory of depression, specifically, that self-generated interpersonal stress results as a consequence of both depressive symptoms and underlying cognitive, emotional, and/or interpersonal attributes of depression-prone individuals.

While the leading goal of this research was to examine depressive rumination as one characteristic of depression-prone individuals that contributes to dependent interpersonal stress, baseline levels of depressive symptoms were also assessed. Although not depicted in the models to preserve clarity of presentation, W1 depressive symptoms also significantly predicted elevations in dependent interpersonal stress over time beyond the contribution of depressive rumination (β = .19, P <.05). Thus, support was garnered for both components of the stress generation theory in that depressive symptoms and characteristics of depression-prone individuals made unique prospective contributions to increases in dependent interpersonal stress.

The final key finding of this research was that both depressive ruminative response style and the generation of interpersonal stress made independent contributions to subsequent depressive symptoms, but dependent interpersonal stress did not account for the association between depressive rumination and depressive symptoms over time. These results cohere with both cognitive and interpersonal stress generation models of depression, and are important in terms of refining our understanding of the integration of these two models. That is, the obtained pattern of results indicates that cognitive vulnerability (i.e., depressive rumination) directly contributed to the development of depressive symptoms; in tandem, cognitive vulnerability contributed to interpersonal vulnerability (i.e., relationship disturbances), and the ensuing self-generated interpersonal stress made a direct independent contribution to depressive symptoms beyond that of cognitive vulnerability. Thus, it will be fruitful for future research to simultaneously examine associations between cognitive vulnerability and interpersonal stress generation as they jointly contribute to depressive symptoms. It is important to note that rumination was only assessed at the first wave of this study, which precluded the examination of the interplay between rumination and interpersonal stress generation over time. An important goal for future research will be to explore reciprocal and transactional influences among cognitive and interpersonal attributes that contribute to the onset, maintenance, and recurrence of depressive symptoms across development.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This investigation has several strengths. These include the inclusion of a large sample of nondepressed individuals, standardized life event interviews with objective definitional criteria, life event interviewers blind to scores on all other measures, a prospective longitudinal design, and conservative statistical tests of study hypotheses by adjusting for prior levels of dependent variables in comprehensive structural equation models.

However, it is important to consider the limitations of this research as well. In terms of sample characteristics, this study consisted of undergraduate students, which although ethnically and socioeconomically diverse, may not be representative of community samples. Moreover, as the overall levels of depressive symptoms in this sample were not in the clinical range, the present findings reflect variation in subclinical depressive symptoms. Accordingly, replication of the obtained models in both community and clinical populations represent important avenues for future research. Finally, depressive rumination, social support perceptions, and depressive symptoms were assessed via self-report. Although the self-report measures chosen for this study are reliable and valid assessments of these constructs, future tests of prospective associations among depressive rumination, social support perceptions, life stress, and depressive symptoms may benefit from the use of task-based measures of depressive rumination, and interview-based measures of perceived social support and depressive symptoms.

Clinical Implications

The results of this research have important implications in terms of refining and integrating depression-focused treatment modalities. That is, instead of targeting cognitive and interpersonal risk factors independently, efforts should be directed toward educating depressed individuals about the manner in which maladaptive cognitions have a detrimental influence on both intra- and interpersonal functioning. Evidence from this study specifically suggests that depression-focused treatment endeavors might benefit from a combined emphasis on (a) the identification and disruption of the intrapersonal cognitive cycle of depressive rumination, (b) the promotion of adaptive social support seeking skills, and (c) psychoeducation regarding the connection between depressogenic behaviors and relationship disturbances, in addition to the ensuing contribution of interpersonal dysfunction to the maintenance and recurrence of depressive symptoms.

Footnotes

To investigate whether cognitive risk status influenced any patterns of effects, supplemental path analyses were conducted that controlled for cognitive risk status. Including cognitive risk status did not alter the significance of the paths between any of the key study variables, and significantly decreased the strength of the model fit indices. Accordingly, the reported results do not adjust for cognitive risk status.

Interpersonal events reflecting perceptions of social support were removed from analyses due to content overlap with social support discontent (i.e., “Had no one to confide in,” “Had fewer friends than would like or rarely sought out by others for activities,” “Rarely received affection, respect, or interest from friends,” “Live alone and see other people less often than would like”).

Contributor Information

Megan Flynn, Department of Psychology, Temple University, 1701 North 13th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA, megan.flynn@temple.edu.

Jelena Kecmanovic, Argosy University, Washington, DC, USA.

Lauren B. Alloy, Department of Psychology, Temple University, 1701 North 13th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA

References

- Abela JRZ, Vanderbilt E, Rochon A. A test of the integration of the response styles and social support theories of depression in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23:653–674. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Adams P, Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Factorial categorization of depression-related constructs in early adolescents. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 2007;21:123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY. The temple-wisconsin cognitive vulnerability to depression (CVD) project: Conceptual background, design, and methods. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 1999;13:227–262. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, Rose DT, Robinson MS, et al. The temple-wisconsin cognitive vulnerability to depression project: Lifetime history of Axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:403–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Nereen AM. Cognitive vulnerability to unipolar and bipolar mood disorders. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006a;25:726–754. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME, Panzarella C, Rose DT. Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006b;115:145–156. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Clements CM. Illusion of control: Invulnerability to negative affect and depressive symptoms after laboratory and natural stressors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:234–245. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bottonari KA, Roberts JE, Kelly MAR, Kashdan TB, Ciesla JA. A prospective investigation of the impact of attachment style on stress generation among clinically depressed individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Alpert D, Lent RW, Hunt G, Brady T. Perceived social support among college students: Factor structure of the Social Support Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1988;35:472–478. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Brady T, Lent RW, Wolfert J, Hall S. Perceived social support among college students: Three studies of the psychometric characteristics and counseling uses of the social support inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34:337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:186–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley SE, Hammen C, Burge D, Davila J, Paley B, Lindberg N, et al. Predictors of the generation of episodic stress: A longitudinal study of late adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:251–259. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley SE, Rizzo CJ, Gunderson BH. The longitudinal relation between personality disorder symptoms and depression in adolescence: The mediating role of interpersonal stress. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2006;20:352–368. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Hammen C, Burge D, Paley B, Daley SE. Poor interpersonal problem solving as a mechanism of stress generation in depression among adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:592–600. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL. A diagnostic interview: The schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn M, Rudolph KD. Stress generation and adolescent depression: Predictive contribution of maladaptive responses to interpersonal stress; Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; Chicago, IL. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel G, Gibb BE, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hankin BL, et al. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression: Development and validation of the cognitive style questionnaire. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:824–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Depression runs in families: The social context of risk and resilience in children of depressed mothers. New York, NY: Springer; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Cognitive, life stress, and interpersonal approaches to a developmental psychopathology model of depression. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:1065–1082. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Kassel JD, Abela JRZ. Adult attachment dimensions and specificity of emotional distress symptoms: Prospective investigations of cognitive risk and interpersonal stress generation as mediating mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:136–151. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. Depression’s vicious scree: Self-propagating and erosive processes in depression chronicity. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2000;7:203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Coyne JC. The interactional nature of depression. Washington, DC: APA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Just N, Alloy LB. The response styles theory of depression: Tests and an extension of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:221–229. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Caldwell ND, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of ruminative and distracting responses to depressed mood on retrieval of autobiographical memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:166–177. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Self-perpetuating properties of dysphoric rumination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:339–349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:176–190. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multon KD, Brown SD. A preliminary manual for the social support inventory (SSI) Chicago: Loyola University of Chicago, Department of Counseling and Educational Psychology; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Needles DJ, Abramson LY. Positive life events, attributional style, and hopefulness: Testing a model of recovery from depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:156–165. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Davis CG. “Thanks for sharing that”: Ruminators and their social support networks. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:801–814. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:115–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Parker LE, Larson J. Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;61:92–104. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Opening up: The healing power of confiding in others. New York, NY: Morrow; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31:539–548. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff JG, Holahan CJ, Joiner TE. Reassurance seeking, stress generation, and depressive symptoms: An integrative model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:664–670. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Borelli JL, Cheah CSL, Simon VA, Aikins JW. Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:676–688. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD. Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M, Abaied JL. A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Child and adolescent depression: Causes, treatment, and prevention. New York, NY: Guilford; 2007. pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M, Abaied JL, Groot AK, Thompson RJ. Why is past depression the best predictor of future depression? Stress generation as a mechanism of depression continuity in girls. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:473–485. doi: 10.1080/15374410902976296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safford SM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Crossfield AG. Negative cognitive style as a predictor of negative life events in depression-prone individuals: A test of the stress-generation hypothesis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;99:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. Understanding the relationship between emotional and behavioral dysregulation: Emotional cascades. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:593–611. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH. Sex differences in stress generation: An examination of sociotropy/autonomy, stress, and depressive symptoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:434–446. doi: 10.1177/0146167205282739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology 1982. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: Tuma N, editor. Sociological methodology 1986. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1986. pp. 159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Spasojevic J, Alloy LB. Rumination as a common mechanism relating depressive risk factors to depression. Emotion. 2001;1:25–37. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasojevic J, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, MacCoon DG, Robinson MS. Reactive rumination: Outcomes, mechanisms, and developmental antecedents. In: Papageorgiou C, Wells A, editors. Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment. New York, NY: Wiley; 2003. pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock LM, Whisman MA. Rumination and excessive reassurance-seeking in depression: A cognitive-interpersonal integration. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2007;31:333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Weisman A, Beck AT. Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale: A preliminary investigation. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Educational Research Association; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 1978. [Google Scholar]