Abstract

Objective

The primary objective of this study was to determine if contingency management was associated with increased stimulant drug abstinence in community mental health outpatients with serious mental illness and stimulant dependence. Secondary objectives were to determine if contingency management was associated with reductions in use of other substances, psychiatric symptoms, HIV-risk behavior, and inpatient service utilization.

Method

A randomized controlled design compared outcomes of 176 outpatients with serious mental illness and stimulant dependence. Participants were randomized to three months of contingency management for stimulant abstinence plus treatment-as-usual or treatment-as-usual with reinforcement for study participation only. Urine drug tests, self-report, clinician-report, and service utilization outcomes were assessed during three-month treatment and three-month follow-up periods.

Results

While participants in the contingency management condition were less likely to complete the treatment period (n=38; 42%) than those assigned to the control condition (n=55; 65%), X2(1)=9.8, p=0.02; those assigned to the contingency management condition were 2.4 (CI=1.9-3.0) times more likely to submit a stimulant-negative urine test during treatment. Participants assigned to contingency management experienced significantly lower levels of alcohol use, injection drug use, psychiatric symptoms, and were five times less likely than those assigned to the control condition to be admitted for psychiatric hospitalization, X2(1)=5.4, p=0.02. Contingency management participants reported significantly fewer days of stimulant drug use, relative to controls during the three-month follow-up.

Conclusions

When added to treatment-as-usual, contingency management is associated with large reductions in stimulant, injection drug, and alcohol use. Reductions in psychiatric symptoms and hospitalizations were important secondary benefits.

Approximately 50% of adults with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia spectrum, bipolar, and recurrent major depressive disorders, suffer from a substance use disorder at some point during their lives (1). Relative to people with only one of these conditions, individuals with co-occurring disorders have more severe substance use and psychiatric symptoms (2), poorer treatment adherence (3), increased homelessness (4), higher rates of HIV infection (2), psychiatric hospitalization (5), emergency room use (6), and incarceration (7).

Despite the frequent co-occurrence of these disorders and associated detrimental outcomes, few individuals receive concurrent treatment for both conditions (8, 9). Integrated treatments delivered via individual (10, 11), group (12), case management (13), or multiple component (14) models have been associated with reductions in drug use. While these treatments have been associated with reduced psychiatric severity in some studies, other studies have not observed reductions in psychiatric severity (15). Further, few individuals receive such treatments in community mental health centers , where most adults with co-occurring disorders receive care (8), due to factors including the cost of these interventions, organizational barriers, and the need for extensive training and adherence to these models (16-18).

Interventions that are less costly and easier to implement (e.g., do not require clinical staff, extensive training, supervision and adherence ratings) are needed to improve outpatient treatment co-occurring disorders treatment. Contingency management is an evidence-based intervention where individuals are provided with reinforcers (e.g., vouchers, prizes) based on abstinence from drugs. Contingency management is associated with the largest reductions in drug and alcohol use compared to all other psychosocial treatments (19). Contingency management has also demonstrated improved treatment retention and/or attendance(20, 21) and long-term efficacy (22, 23) in non-seriously mentally ill populations. Initial evidence suggests similar improvements in treatment retention and abstinence for persons with serious mental illness (24, 25). Bellack and colleagues (14) observed reductions in drug use and hospitalizations, as well as increases in quality of life and financial management in adults with co-occurring disorders who received a six-month cognitive behavioral group-based treatment that included contingencies for drug abstinence. These data suggest that contingency management may be an effective treatment approach for adults with COD. However, no adequately powered, randomized controlled trial has been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of contingency management alone as an adjunct to treatment as usual for substance use disorders in seriosly mentally ill outpatients.

The primary aim of this study was to determine if the addition of contingency management for psycho-stimulant drug abstinence was successful in reducing stimulant drug use, as measured by urine drug tests and self-report, in persons with serious mental illness and stimulant use disorders receiving treatment in a community mental health center. Secondary aims were to determine if contingency management was associated with reductions in other drug and alcohol use, drug use severity, psychiatric severity, HIV-risk behavior, and community problems (e.g., psychiatric hospitalizations, incarcerations). Stimulant drugs were targeted because of the frequent abuse of these drugs by those with serious mental illness and the association between stimulant use and psychiatric symptom exacerbation (26).

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from a multisite community mental health and addiction treatment agency in Seattle, Washington and met Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) criteria for methamphetamine, amphetamine or cocaine dependence, and schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I or II, or recurrent major depressive disorder (Table 1). To be eligible participants had to have used stimulants during the last 30 days. Exclusion criteria were medical or psychiatric severity that would compromise safe participation, an organic brain disorder, or dementia.

Table 1. Psychiatric and substance use disorder characteristics of the evaluative sample (N=176).

| Contingency Management (N=91) |

Non-Contingent Control (N=85) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| n | % | Mean | (SD) | n | % | Mean | (SD) | |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||||

| Female | 31 | 34% | 30 | 35% | ||||

| Caucasian | 46 | 50% | 49 | 57% | ||||

| African American | 31 | 34% | 22 | 26% | ||||

| Other | 14 | 15% | 14 | 16% | ||||

| Age | 43.01 | (9.27) | 42.45 | (9.97) | ||||

| Homeless or unstable housing | 59 | 56% | 56 | 66% | ||||

| Psychiatric Characteristics | ||||||||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 26 | 29% | 21 | 25% | ||||

| Bipolar disorder | 30 | 33% | 30 | 35% | ||||

| Schizoaffective-spectrum disorder | 35 | 39% | 34 | 40% | ||||

| Inpatient psychiatric care in the last year | 30 | 33% | 29 | 34% | ||||

| Substance Use Characteristics | ||||||||

| Current substance use disorders | ||||||||

| Cocaine dependence | 88 | 96% | 80 | 94% | ||||

| Amphetamine or methamphetamine dependence | 32 | 35% | 36 | 42% | ||||

| Non-stimulant drug abuse or dependence | 52 | 57% | 59 | 58% | ||||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 43 | 47% | 37 | 44% | ||||

| Days of substance use in the 30 days prior to study entry | ||||||||

| Cocaine | 6.00 | (7.28) | 6.53 | (7.65) | ||||

| Amphetamines | 0.65 | (1.84) | 0.80 | (2.86) | ||||

| Alcohol | 5.46 | (7.21) | 6.61 | (9.67) | ||||

| Cannabis | 3.55 | (7.95) | 2.99 | (7.37) | ||||

| Opioids | 1.72 | (5.45) | 0.89 | (3.04) | ||||

| Misc. drug | 0.30 | (1.66) | 0.95 | (4.33) | ||||

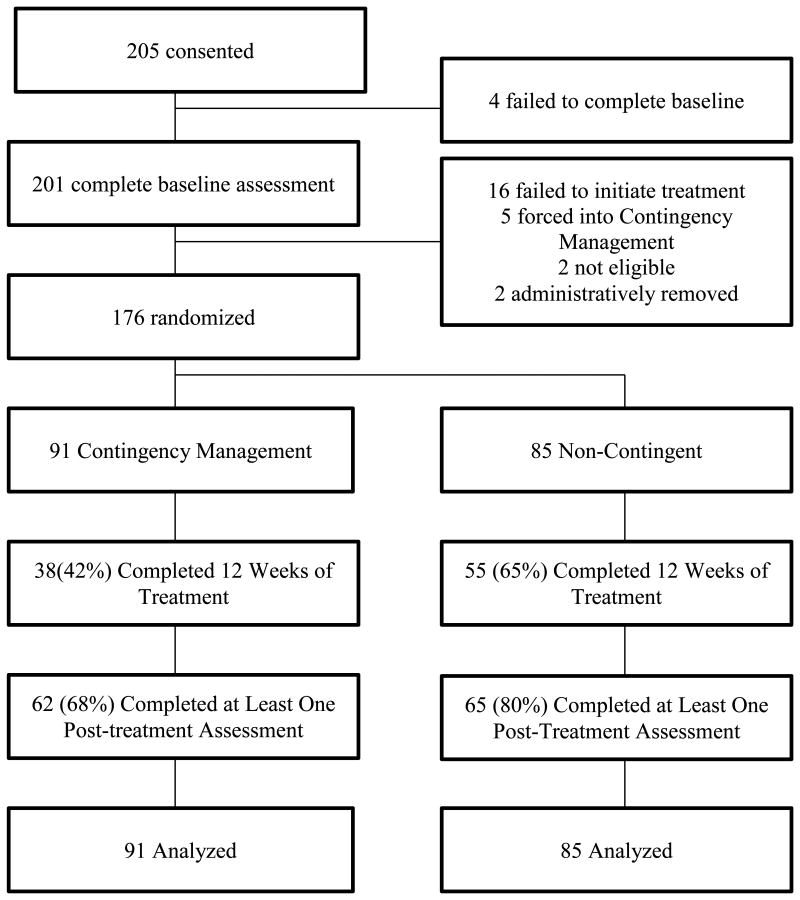

205 individuals provided written informed consent for study participation, 201 completed the initial study assessment, and 197 met criteria for inclusion (Figure 1). Consistent with previous studies that utilized a non-contingent reinforcement control condition (27) the first five participants were assigned to the contingency management condition. Of the 192 individuals available for randomization, 176 returned for their second study visit where they were informed of their group assignment and are considered the intent-to-treat sample. Study procedures were approved by the University of Washington's Human Subjects Division.

Figure 1. Study consort diagram.

Design and Procedure

This study employed a three-month quasi-yoked randomized controlled trial of contingency management with a three-month post-treatment follow-up period. Participants were randomized to contingency management (contingent) plus treatment-as-usual (n=91) or treatment-as-usual plus rewards for study participation only (non-contingent rewards; n=85). Randomization was conducted using the urn-randomization procedure (28) balancing groups on gender, substance use severity, mood vs. psychotic disorder, and psychiatric hospitalization in the last year.

Measures

Participants completed a structured psychiatric interview and study outcome measures. During the treatment phase, participants provided alcohol breath samples (Alco-Sensor-III, Intoximeters, Inc., St. Louis, MO) and urine samples for drugs. Drugs were assessed using onsite immunoassays of amphetamine, methamphetamine, cocaine, marijuana, and opiate use (Integrated E-Z Split Key® Cup, Innovacon, Inc, San Diego, CA.). Participants provided breath and urine samples three times per week (Monday/Wednesday/Friday) and received prize draws as stipulated by their test results and experimental condition. Participants provided breath and urine samples once per month during the follow-up period. At weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 participants completed other study outcome measures assessing days of substance use and substance use severity (Addiction Severity Index-lite), psychiatric symptom severity (Brief Symptom Inventory; Positive and Negative Symptom Scale), and HIV-Risk Behavior (HIV-Risk Behavior Scale). Participants were reimbursed for completing these interviews.

Community outcomes were gathered from administrative sources for the three months prior to randomization, the three-month intervention period, and the three-month follow-up. Data included counts of outpatient mental health and chemical dependency visits, inpatient substance use and psychiatric treatment admissions and days, detoxification admissions, emergency room utilization, and incarcerations.

Treatment-as-Usual

Treatment-as-usual consisted of mental health, chemical dependency, housing, and vocational services. Most clients saw their case manager once per week, had access to psychiatric medication management, and could participate in various group treatments. Forty-six percent (n=42) and 54% (n=46) of individuals in the contingent and non-contingent groups, respectively, received intensive outpatient group and/or individual substance abuse treatment during the study.

Treatment Conditions

Contingent Group

Participants assigned to the contingent group received the variable magnitude of reinforcement procedure (reinforcement procedure) each time they tested negative for amphetamine, methamphetamine, and cocaine. This procedure is well researched (29) and involves making “draws” from a bowl of tokens representing different magnitudes of reinforcement. Fifty percent read “good job” (no tangible reinforcer). The other 50% were associated with a tangible prize (41.8% read “small” $1.00 value, 8% read “large” $20.00 value, and 0.2% read “jumbo” $80.00 value). Participants began by earning one opportunity to engage in the reinforcement procedure for each urine sample that demonstrated abstinence. One additional opportunity to engage in the reinforcement procedure was earned for each week of continuous stimulant abstinence. Missing or drug-positive samples resulted in no delivery of reinforcement at that visit and a reset to one in the number of opportunities to engage in the reinforcement procedure when the next negative sample was submitted. Following a reset, participants could return to the point in the escalation at which the reset occurred by providing three consecutive stimulant-negative samples. Participants were provided with one additional opportunity to engage in the reinforcement procedure during each visit if they submitted samples that demonstrated alcohol, opioids, and marijuana abstinence.

Non-Contingent Control Group

Consistent with previous studies, participants in the non-contingent control group were quasi-yoked to participants in the contingent group (27) in order to equate the number of prize draws received between conditions, while isolating the contingent nature of reinforcement for drug abstinence. To determine the number of prize draws received by individuals assigned to the non-contingent group in the first week of the study, the first five individuals recruited to the study were ‘forced’ into the contingent condition. These individuals were treated for one week and their average number of prize draws was used to set the number of prize draws received by non-contingent participants during their initial week of participation. For the remainder of the study the number of prize draws of the non-contingent condition was equal (yoked) to the average number of draws earned by the contingent group during the prior week. The five individuals ‘forced’ into the contingent group were not included in the intent-to-treat sample.

Reinforcers and Earnings

Reinforcers were consistent with recovery and included shampoo, toothpaste, gift cards, microwaves, and electronics. The total average value of prizes earned for the non-contingent and contingent groups were, $201.48 (SD=$343.32) and $150.30 (SD=$130.94), respectively (not statistically different).

Data Analysis

Using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables (including outcomes) groups were not statistically different in terms of baseline demographic, clinical, or outcome variables. Analyses were conducted on the intent-to-treat sample. Generalized estimation equations were used for the analyses conducted on outcomes that were measured over time in conjunction with the robust maximum likelihood estimation procedure to protect against a Type-I error (30). Analyses utilized bi-directional tests despite our hypotheses being uni-directional to further protect against a Type-I error. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are presented for binary outcomes. Unstandardized regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals are presented for continuous outcomes. This method of analysis has been used in previous contingency management trials and is an effective and efficient method of analyzing outcomes across time nested within participants (20, 29). Generalized estimation equations were used to evaluate the significance of changes in outcomes over time by treatment condition.

Multiple imputation procedures were used to handle missing data in primary and secondary outcome analyses. This approach has significant advantages over single imputation or listwise deletion (31) or other techniques (32, 33) in conjunction generalized estimation equation analyses and has frequently been used in psychiatric studies with similar levels of missing data (34, 35). Multiple imputations requires the assumption of ‘missing at random.’ This method of is a more conservative approach compared to the default listwise deletion used in generalized estimation equations analyses which assumes ‘missing completely at random.’ Preliminary analyses identified 12 variables that predicted missingness due to treatment dropout. We used these variables during the imputation phase to help ensure that our ‘missing at random’ assumption was tenable. While there is no test for whether missing data are truly ‘missing at random’ versus ‘missing not at random,’ our inclusive strategy for auxiliary variables (i.e., variables used during the imputation, but not the analysis phase) during the imputation phase made for a tenable assumption that data were ‘missing at random.’ Multiple imputation procedures use a regression-based approach to fill in the missing values to produce multiple datasets. In order to maximize the efficiency of our standard errors, 50 datasets were analyzed for each analysis. Parameters and standard errors were combined using Rubin's rules (31). Analyses were performed using Stata-11.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). We performed extensive sensitivity analyses in order to assess the relative stability of the effect of treatment on the primary outcome (psycho-stimulant abstinence) across different missing data handling techniques. In addition to the multiple imputation analysis, we performed analyses that used listwise deletion and last observation carried forward on both the intent-to-treat sample and the treatment completers only. In addition, we performed latent growth curve modeling that utilized maximum likelihood using Diggle-Kenward Selection and Wu-Carroll Selection modeling. While we attempted to fit a basic Pattern Mixture Model (32,33), convergence proved difficult and we were not able to obtain parameter estimates.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are described in Table 1 (no statistically significant group differences were observed).

Participants were considered treatment-dropouts if they were absent from nine consecutive study appointments (i.e., 3 weeks) during the study treatment phase. Significantly fewer contingent condition participants were retained throughout treatment (n=38; 42%), relative to non-contingent participants (n=55; 65%), X2(1)=9.8, p<0.05. Contingent participants were retained for fewer weeks (Mean=7.25; SD=4.25) than those who received non-contingent reinforcement (Mean=9.33; SD=3.98). Dropout typically occurred during the first four weeks (Contingent n=34, 64%; Non-contingent n=19, 63%,).

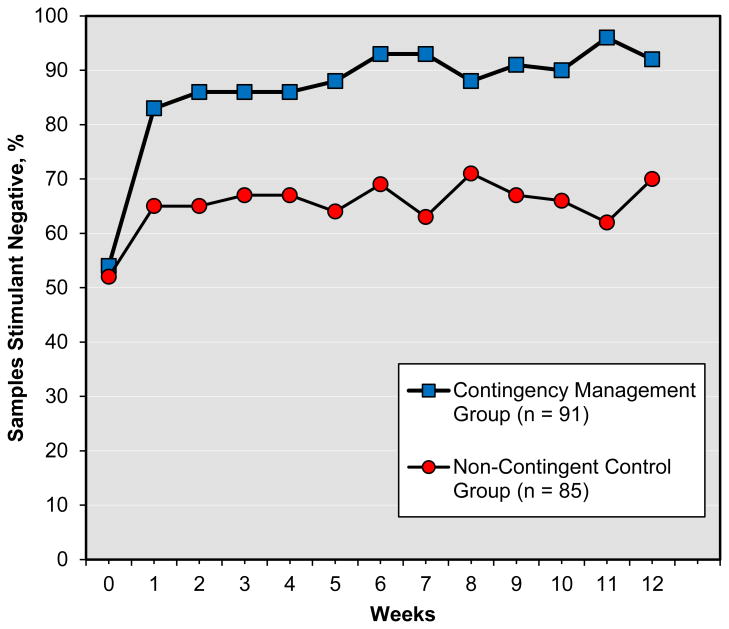

Analyses conducted on the intent-to-treat sample revealed that participants in the contingent condition were 2.4 (CI=1.9-3.0, p<0.05) times more likely to submit a stimulant-negative urine sample during the treatment period (3 urine tests submitted per week, for 12 weeks) relative to controls. The proportion of stimulant-abstinent participants (assessed by urine tests) by group across each of the 12 weeks of treatment are displayed in Figure 1. Results of all sensitivity analyses conducted on the intent-to-treat and treatment completer samples observed a similar statistically significant group effect on stimulant abstinence. During follow-up, contingent participants were more likely to submit a stimulant-negative urine test (n=42, 46%), relative to non-contingent participants (n=30, 35%), OR=1.4 (CI=1.0-1.9), p<0.05 using multiple imputation procedures. However, a significant group difference at follow-up was inconsistently observed in sensitivity analyses.

Participants assigned to the contingent condition reported significantly fewer days of self-reported stimulant use during treatment, β=2.70 (CI=0.91-4.31), p<0.05, and follow-up, β=2.16 (CI=0.18-3.24), p<0.05, relative to non-continent participants. Table 2 summarizes descriptive statistics for outcomes that demonstrated statistically significant group differences. Contingent participants reported fewer days of alcohol use, relative to those in the non-contingent group, during treatment, β=2.44 (CI=0.60-4.29), p<0.05, but not follow-up. All other measures of other drug use and Addiction Severity Index-lite composite scores were not different across groups.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for primary and secondary outcomes during in-treatment and post-treatment follow-up time periods (N=176)*.

| In treatment | Follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Contingency Management (n=91) |

Non-Contingent Control (n=85) |

Contingency Management (n=52)# |

Non-Contingent Control (n=55)# |

|||||

|

| ||||||||

| Outcome Variable | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) |

| Days of stimulant use | 0.91 | (2.40) | 4.67 | (7.69) | 1.83 | (4.94) | 3.65 | (7.15) |

| Days of alcohol use | 1.84 | (4.77) | 4.32 | (8.43) | 3.60 | (7.92) | 4.21 | (7.86) |

| Brief Symptom Inventory Score | 1.04 | (0.79) | 1.24 | (0.71) | 1.17 | (0.85) | 1.25 | (0.79) |

| Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale Excitement Factor Score | 10.60 | (2.58) | 11.69 | (3.42) | 11.17 | (3.18) | 11.57 | (3.01) |

| n | % | n | % | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Injection drug use | 34 | 37% | 56 | 66% | 23 | (44) | 31 | (56) |

|

| ||||||||

| Outcomes Assessed Across Entire 6 Months Post- Randomization | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Contingency Management (n=91) |

Non-Contingent Control (n=85) |

|||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Psychiatric hospitalization, No % Sum days of psychiatric hospitalization | n=2 | 2% | n=9 | 10% | ||||

| 14 | 152 | |||||||

Note: Bold text indicates statistically significant group differences, p<0.05.

Note: While the use of multiple imputation techniques allowed for us to include the entire sample (N=176) in our inferential statistical tests of treatment outcomes, in this Table the original raw data (without imputation) were used to generate descriptive statistics.

Note: During the follow-up period 43% (n=39) and 36% (n=30) participants in the contingency management and non-contingent control condition, respectively did not provide data that could be descriptively analyzed.

No group differences were observed in HIV-risk associated sexual behavior. Approximately 24% (Contingent=23%, n=21; Non-contingent=25%, n=21) of the sample reported injecting illicit drugs in the month prior to study entry. Participants assigned to the contingent group were 3.3 times (CI=1.8-5.9, p<0.05) less likely to report engaging in injection drug use, relative to non-contingent participants, during treatment. Groups were not different during follow-up.

Contingent participants reported lower levels of psychiatric symptoms on the Brief Symptom Inventory, relative to those in the non-contingent condition during treatment, β=0.25 (CI=0.08-0.43), p<0.05. Participants assigned to the contingent condition also had lower Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ratings on the excitement subscale, β=0.86 (CI =0.11-1.60), p<0.05, relative to non-contingent participants during treatment. Groups were not different on these measures during the follow-up period. One individual from each group was admitted for a psychiatric hospitalization during the three-months prior to randomization (length of stay: Contingent=24 days, Non-contingent=6 days). During the six months following randomization, 2% (n=2) of participants in the contingent condition were admitted for inpatient psychiatric care, while 10% (n=9) of participants in the non-contingent condition were admitted, X2(1)=5.4, p=0.02. Groups were also different in terms of the total number of days hospitalized (Contingent=14 days, Non-contingent=152). Groups did not differ on other community outcomes.

Patient Perspective

The patient was a 55 years-old woman diagnosed with bipolar disorder. She wanted to stop using cocaine but that her family, whom used regularly, placed a great deal of pressure on her to continue using. The patient responded well to the contingency management intervention, and maintained abstinence from all drugs for six months. She reported that “the prizes gave me a reason to stay sober and something to look forward to besides using.” She also reported that her family stopped using cocaine in her presence because “they wanted me to keep bringing prizes home.”

Discussion

This is the first large randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of a contingency management intervention for drugs of abuse as an adjunct to treatment-as-usual in a typical outpatient setting. Those who received the contingency management intervention were 2.4 times more likely to submit a stimulant-negative urine sample during treatment, relative to those in the control condition. Contingency management also had a positive impact on substance use and psychiatric outcomes that were not the primary focus of the intervention. Relative to those assigned to the control condition, individuals who received contingency management experienced reductions in alcohol use, HIV-risk behavior (injection drug use), psychiatric symptoms, and inpatient care. Consistent with previous research in stimulant-abusing adults (36) without serious mental illness, contingency management was associated with reduced injection drug/HIV-risk in our sample. Reductions in injection drug use are of particular public health relevance given the relatively high comorbidity of stimulant and injection drug use (approximately 25%) observed in this sample.

Group differences in psychiatric symptoms were corroborated by differences in inpatient psychiatric utilization. In comparison to those in the control condition, those randomized to receive contingency management were 5 times less likely to be admitted for a psychiatric hospitalization during the post-randomization time period. Changes in substance use, psychiatric symptoms, and inpatient psychiatric care observed in the current study were equivalent to previous studies of more comprehensive and costly co-occurring disorder psychosocial interventions that are currently the gold standard for evidence-based treatment (10-13), suggesting that contingency management in combination with treatment-as-usual may be a viable alternative to these treatments.

Data suggest that an effect of contingency management on stimulant abstinence persisted after treatment was discontinued. While results of multiple imputation analyses suggested higher levels of stimulant abstinence in the contingent group, relative to the non-contingent group during the follow-up period, results of sensitivity analyses yielded inconsistent results (only the multiple imputations technique showing a statistically significant group difference). Lower levels of self-reported stimulant use were observed during the follow-up period by participants in the contingent group relative to controls. While these differences in self-reported stimulant use is consistent with previous studies in non-seriously mentally ill populations that observed treatment effects up to one year after completion (22), this result should be interpreted with caution given the high level of missing data during follow-up.

Group differences in primary and secondary outcomes were observed despite the fact that the contingency management dropout rate was somewhat higher (59%) than has been previously observed in stimulant-abusing populations (approximately 50%) (20). The higher rate of treatment dropout in this study likely reflects the psychiatric comorbidity in this sample, and that 66% of our sample was homeless. While groups did not differ in terms psychiatric severity or homelessness, it is possible that lower functioning individuals were more likely to consistently attend study sessions when provided with reinforcement for attendance, but not when the additional contingency of abstinence was added. Others have found that treatment completion is improved after exposing patients to an initial period of non-contingent reinforcement (37). This and other approaches (e.g., providing higher value rewards, such as housing (38), or adding contingency management to evidence-based treatments for mental illness) might improve treatment retention in this population.

This is the second study in a co-occurring disordered population to find that contingency management can be delivered at a low cost. The cost of urine testing and reinforcers was $256 per participant for the entire treatment group ($864 for individuals with ≥8 weeks abstinence). In this sample, individuals assigned to the contingent condition experienced 138 fewer days of psychiatric hospitalization, relative to those in the control condition. Though few subjects in either group were hospitalized (Contingent n=2; Non-contingent n=9) and differences in hospitalization rates might be due in part to chance, evidence from this study suggests that savings related to reductions in psychiatric hospitalization could offset the costs of contingency management.

Despite empirical support, potential cost savings, and characteristics that suggest that contingency management could be disseminated into clinical practice, it has not been fully utilized in clinical practice. The primary barriers to dissemination appear to be financial, rather than clinical or theoretical objections by clinicians (39). While the cost of delivering contingency management increases when individuals respond to the treatment (they receive more prizes), this increase is modest compared to savings in inpatient care demonstrated in this and other studies (14). While a number of innovative strategies have been explored to provide funding for contingency management reinforcers (e.g., use of donated funds/prizes, opportunities to work) (37), it is likely that contingency management will continue to be underutilized until payers provide funding for the costs of delivering this treatment. An example of this type of reform recently occurred within the Veteran's Administration where contingency management has been approved as a treatment of illicit drug use in veterans receiving intensive outpatient treatment (40).

The generalizability of study results may be limited because recruitment for this study occurred at one large treatment agency. Methodologically, the lower treatment completion rate in the contingent condition, relative to the non-contingent condition, resulted in group differences in rates of missing data. However, we utilized robust statistical methods (i.e., multiple imputation), that have been frequently used in psychiatric research where comparable levels of missing data were observed (34, 35), to account for missing data (see the Data Analysis section) and conducted multiple sensitivity analyses to corroborate the findings of our multiple imputation approach. Despite these consistent results, it is important to note that all imputation strategies bias study results, with some (e.g., single imputation) introducing more bias than others.

Despite study limitations, results provide evidence that contingency management is an effective technique for reducing drug and alcohol use, HIV-risk behavior, psychiatric symptoms, and rates of inpatient hospitalization in seriously mentally ill adults. If financial and other barriers to dissemination can be overcome, contingency management might be an effective adjunctive treatment for this population. Future research investigating the efficacy of contingency management in this population should focus on identifying strategies to improve treatment retention and how contingency management might be optimally combined with other evidence-based psychiatric interventions to further improve outcomes.

Figure 2. Percent of participants with stimulant-negative urine samples across the baseline (week 0) and 12-week treatment periods.

Note: Those assigned to the contingency management group were 2.4 (CI=1.9-3.0, p<0.05) more likely to submit a stimulant-negative urine test, relative to those in the non-contingent control group during the 12-week treatment period. While the use of multiple imputation techniques allowed for us to include the entire sample (N=176) in our inferential statistical tests of treatment outcomes, the original raw data (without imputation) are displayed in this Figure.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the leadership and staff at Community Psychiatric Clinic, Including Shirley Havenga, Kelli Nomura, Susan Peacy, Liz Quakenbush, Amanda Wager, Kurt Davis, and many others for their support of this project.

Author Note: Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, R01 DA022476-01 (Primary Investigator: R.K. Ries)

Footnotes

Previously presented at The 22nd Annual Meeting and Symposium of The American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry (AAAP), December 8-11, 2011 in Scottsdale, AZ.

Disclosures: Dr. Ries has been on the speaker bureaus of Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen, Astra-Zeneca, and Suboxone in the past five years. Drs. Roll and McPherson have received research funding in the past twelve months from Bristol-Myers Squibb. All other authors have no disclosures to report.

Literature cited

- 1.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LJ, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264:2511–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.RachBeisel J, Scott J, Dixon L. Co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: a review of recent research. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(11):1427–34. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett ME, Bellack AS, Gearon JS. Treating substance abuse in schizophrenia. An initial report. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;20(2):163–75. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galanter M, Dermatis H, Egelko S, De Leon G. Homelessness and mental illness in a professional- and peer-led cocaine treatment clinic. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(4):533–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, Cavanaugh JL, Jr, Davis JM, Lewis DA. Predicting the “revolving door” phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(6):856–61. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartels SJ, T GB, Drake RE, Clark RE, Bush PW, Noordsy DL. Substance Abuse in Schizophrenia: Service Utilization and Costs. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1993;181(4):227–32. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abram KM, Teplin LA. Co-occurring disorders among mentally ill jail detainees. Implications for public policy. Am Psychol. 1991;46(10):1036–45. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.10.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watkins KE, Burnam AB, Kung F, Paddock S. A national survey of care for persons with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(8):1062–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.8.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein JF, Hourani LL, Heller DC. Predictors of treatment receipt among adults with a drug use disorder. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(4):841–69. doi: 10.1081/ada-200037550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrowclough C, Haddock G, Wykes T, Beardmore R, Conrod P, Craig T, Davies L, Dunn G, Eisner E, Lewis S, Moring J, Steel C, Tarrier N. Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy for people with psychosis and comorbid substance misuse: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2010;341:6325. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6325. - [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker A, Bucci S, Lewin TJ, Kay-Lambkin F, Constable PM, Carr VJ. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for substance use disorders in people with psychotic disorders: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;188:439–448. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.5.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Jaffee WB, Bender RE, Graff FS, Gallop RJ, Fitzmaurice GM. A “community-friendly” version of integrated group therapy for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;104(3):212–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Clark RE, Teague GB, Xie H, Miles K, Ackerson TH. Assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: a clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(2):201–15. doi: 10.1037/h0080330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellack AS, Bennett ME, Gearon JS, Brown CH, Yang Y. A randomized clinical trial of a new behavioral treatment for drug abuse in people with severe and persistent mental illness. Archives of general psychiatry. 2006;63(4):426–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drake RE, O'Neal EL, Wallach MA. A systematic review of psychosocial research on psychosocial interventions for people with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(1):123–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McFarland BH, Gabriel RM. Datapoints: Service availability for persons with co-occurring conditions. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC) 2004;55(9):978. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakefield PA, Randall GE, Richards DA. Identifying barriers to mental health system improvements: An examination of community participation in Assertive Community Treatment programs. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunette MF, Asher D, Whitley R, Lutz WJ, Wieder BL, Jones AM, McHugo GJ. Implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment: a qualitative analysis of facilitators and barriers. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(9):989–95. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MWCIN. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. Pmid. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petry NM, Peirce JM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Roll JM, Cohen A, Obert J, Killeen T, Saladin ME, Cowell M, Kirby KC, Sterling R, Royer-Malvestuto C, Hamilton J, Booth RE, Macdonald M, Liebert M, Rader L, Burns R, DiMaria J, Copersino M, Stabile PQ, Kolodner K, Li R. Effect of prize-based incentives on outcomes in stimulant abusers in outpatient psychosocial treatment programs: a national drug abuse treatment clinical trials network study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1148–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sigmon SC, Stitzer ML. Use of a low-cost incentive intervention to improve counseling attendance among methadone-maintained patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29(4):253–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rawson RA, McCann MJ, Flammino F, Shoptaw S, Miotto K, Reiber C, Ling W. A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches for stimulant-dependent individuals. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2006;101(2):267–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rawson RA, Huber A, McCann M, Shoptaw S, Farabee D, Reiber C, Ling W. A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches during methadone maintenance treatment for cocaine dependence. Archives of general psychiatry. 2002;59(9):817. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.817. - [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roll JM, Chermack ST, Chudzynski JE. Investigating the use of contingency management in the treatment of cocaine abuse among individuals with schizophrenia: a feasibility study. Psychiatry Res. 2004;125(1):61–4. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ries RK, Dyck DG, Short R, Srebnik D, Fisher A, Comtois KA. Outcomes of managing disability benefits among patients with substance dependence and severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(4):445–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lichlyter B, Purdon S, Tibbo P. Predictors of psychosis severity in individuals with primary stimulant addictions. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:137–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosten T, Oliveto A, Feingold A, Poling J, Sevarino K, McCance-Katz E, Stine S, Gonzalez G, Gonsai K. Desipramine and contingency management for cocaine and opiate dependence in buprenorphine maintained patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(3):315–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 1994;12:70–5. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peirce JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Kellogg S, Satterfield F, Schwartz M, Krasnansky J, Pencer E, Silva-Vazquez L, Kirby KC, Royer-Malvestuto C, Roll JM, Cohen A, Copersino ML, Kolodner K, Li R. Effects of lower-cost incentives on stimulant abstinence in methadone maintenance treatment: a National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):201–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(4):1049–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(2):147–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Enders CK. Missing not at random models for latent growth curve analyses. Psychological methods. 2011;16(1):1–16. doi: 10.1037/a0022640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muthen B, Asparouhov T, Hunter AM, Leuchter AF. Growth modeling with nonignorable dropout: alternative analyses of the STAR*D antidepressant trial. Psychological methods. 2011;16(1):17–33. doi: 10.1037/a0022634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein MD, Solomon DA, Herman DS, Anthony JL, Ramsey SE, Anderson BJ, Miller IW. Pharmacotherapy plus psychotherapy for treatment of depression in active injection drug users. Archives of general psychiatry. 2004;61(2):152–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lapham SC, Stout R, Laxton G, Skipper BJ. Persistence of Addictive Disorders in a First-Offender Driving While Impaired Population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barry D, Weinstock J, Petry NM. Ethnic differences in HIV risk behaviors among methadone-maintained women receiving contingency management for cocaine use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98(1-2):144–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donlin WD, Knealing TW, Needham M, Wong CJ, Silverman K. Attendance rates in a workplace predict subsequent outcome of employment-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in methadone patients. J Appl Behav Anal. 2008;41(4):499–516. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milby JB, Schumacher JE, Wallace D, Freedman MJ, Vuchinich RE. To house or not to house: the effects of providing housing to homeless substance abusers in treatment. American journal of public health. 2005;95(7):1259–65. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.039743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirby KC, Benishek LA, Dugosh KL, Kerwin ME. Substance abuse treatment providers' beliefs and objections regarding contingency management: implications for dissemination. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2006;85(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Administration VH . VHA Programs for Veterans with Substance Use Disorders (SUD) Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2011. [Google Scholar]