Abstract

• Background and Aims Floral nectaries and nectar features were compared between six Argentinian Ipomoea species with differences in their pollinator guilds: I. alba, I. rubriflora, I. cairica, I. hieronymi var. hieronymi, I. indica, and I. purpurea.

• Methods Pollinators were recorded in natural populations. The morpho-anatomical study was carried out through scanning electron and light microscopy. Nectar sugars were identified via gas chromatography. Nectar production and the effect of its removal on total nectar sugar amount were determined by using sets of bagged flowers.

• Key Results Hymenopterans were visitors of most species, while hummingbirds visited I. rubriflora and sphingids I. alba. All the species had a vascularized discoidal nectary surrounding the ovary base with numerous open stomata with a species-specific distribution. All nectar samples contained amino acids and sugars. Most species had sucrose-dominant nectars. Flowers lasted a few hours. Mean nectar sugar concentration throughout the lifetime of the flower ranged from 34·28 to 39·42 %, except for I. cairica (49·25 %) and I. rubriflora (25·18 %). Ipomoea alba had the highest nectar volume secreted per flower (50·12 µL), while in the other taxa it ranged from 2·42 to 12·00 µL. Nectar secretion began as soon as the flowers opened and lasted for a few hours (in I. purpurea, I. rubriflora) or it was continuous during the lifetime of the flower (in the remaining species). There was an increase of total sugar production after removals in I. cairica, I. indica and I. purpurea, whereas in I. alba and I. rubriflora removals had no effect, and in I. hieronymi there was a decrease in total sugar production.

• Conclusions The chemical composition, production dynamics and removal effects of nectar could not be related to the pollinator guild of these species. Flower length was correlated with nectary size and total volume of nectar secreted, suggesting that structural constraints may play a major role in the determination of nectar traits of these species.

Key words: Nectary structure, nectar chemical composition, nectar production dynamics, nectar removal effects, pollinators, Ipomoea, Convolvulaceae, morning glory, Argentina

INTRODUCTION

Floral nectar is widely known as the key reward offered by animal-pollinated plants to their pollen vectors (Proctor et al., 1996). This exudate is secreted by nectaries, i.e. glandular tissues located on various floral parts whose features are significant in plant taxonomy and phylogeny (Fahn, 1979). Sugars dominate the total solutes in floral nectar: these are mainly sucrose, fructose and glucose in varying proportions according to the species (Baker and Baker, 1983a, b; Freeman et al., 1991; Stiles and Freeman, 1993). Other compounds, such as amino acids, phenols, lipids and antioxidants, are found as well, but mostly in trace quantities (Baker and Baker, 1975, 1983a). All these substances often impart a particular taste and odour that may be essential for maintaining certain pollinator groups (Southwick, 1990). In many cases it has been interpreted that pollinators determine nectar components and, thus, the nectar sugar ratios together with flower and inflorescence morphology may be good predictors of the pollinators (cf. Baker and Baker, 1990). For instance, hummingbird- and hawk-moth-pollinated flowers tend to produce sucrose-dominant nectar, whereas bee-pollinated flowers tend to produce nectars with a predominance of hexose (Baker and Baker, 1983a, b). In addition, experimental studies on sugar preferences of hummingbirds have demonstrated that they preferred sucrose solutions instead of equivalent monosaccharide ones (e.g. Martínez del Río, 1990; Stromberg and Johnsen, 1990). However, in other instances nectar composition may be a conservative character due to phylogenetic constraints (cf. Galetto et al., 1998).

Nectar is secreted with particular rhythms, throughout the lifespan of a flower, which allow the nectar production dynamics of a species to be determined. Knowledge of nectar production dynamics is fundamental to the understanding of the plant–animal relationship; aspects such as the plant's strategy of offering nectar, the activity patterns, frequency and diversity of pollinators of a plant species, the rates of nectar consumption by animals, among others, could not be understood without it. Nectar production may show diverse patterns according to the different guilds of pollinators that visit the flowers (e.g. Feinsinger, 1978; Cruden et al., 1983; Galetto and Bernardello, 1992), leading to the assumption that there are coevolutionary relationships between nectar traits and pollinator type (Baker and Baker, 1983a, b). For instance, hawk-moth-pollinated flowers produce abundant nectar with low concentration values and bee-pollinated flowers secrete compartively less nectar with higher concentrations, whereas hummingbird-pollinated flowers show intermediate values (e.g. Pyke and Waser, 1981; Opler, 1983; Baker and Baker, 1983a; Sutherland and Vickery, 1993).

At the same time, the effect of nectar removal by floral visitors may have a pronounced effect on the total amount secreted by a flower. Although in some species removal does not modify nectar production (e.g. Galetto and Bernardello, 1993, 1995; Galetto et al., 2000), in others the total amount of sugar in the nectar may be either increased (e.g. Pyke, 1991; Galetto and Bernardello, 1995; Castellanos et al., 2002) or decreased (e.g. Galetto and Bernardello, 1992; Bernardello et al., 1994; Galetto et al., 1997). Predictions for these patterns are not straightforward because they may be related to pollinators, environmental factors, plant resource allocation, or other factors.

Six sympatrically occurring Ipomoea species that have differences in the pollinator guilds, floral colours and breeding systems were chosen to examine their floral nectaries, nectar components and nectar production dynamics to evaluate if there are correlations among these features and to consider the results in the context of plant–pollinator interactions. Ipomoea (whose species are commonly known as ‘morning glory’) is a cosmopolitan climbing genus from warm and pantropical regions with approx. 650 species (Austin and Huáman, 1996) with large showy flowers that are easy to manipulate. Its members have trumpet-shaped flowers of different colours—mainly white, purple, blue, pink, red (Cronquist, 1981). These are visited by a diverse array of animals, including bees, hawk moths, beetles, butterflies, long-tongued flies, hummingbirds and bats (e.g. van der Pijl, 1954; Vogel, 1954; Schlising, 1970; Sobreira-Machado and Sazima, 1987; McDonald, 1991). These visitors look for the floral nectar secreted by a discoidal nectary surrounding the ovary base (Fahn, 1979; Cronquist, 1981). In addition, extrafloral nectar and nectaries are widespread in Ipomoea in petioles and/or in epals that are mostly visited by ants and serve as a herbivore defence mechanism (Elias, 1983; Keeler and Kaul, 1984).

In spite of the attractiveness of the flowers of this diverse genus and the importance of some species as crops or invas-ives (Austin and Huáman, 1996), studies on the floral nectar features of the genus are few. Only five taxa have been examined for their floral nectar composition (Keeler, 1977, 1980; Stucky and Beckmann, 1982; Freeman et al., 1985, 1991), and only six species have been incidentally examined for their nectar secretion (Real, 1981; Stucky and Beckmann, 1982; Stucky, 1984; Devall and Thien, 1989). The present work was undertaken to study and compare the floral nectaries and nectar features in six Argentinian Ipomoea species addressing the following questions: (1) What are the local flower animal visitors? (2) What is the floral nectary structure? (3) What is the chemical composition of the nectar? (4) What are the production dynamics of nectar throughout the lifetime of the flower? (5) What is the floral response to nectar removal? We expected to find differences in nectar sugar composition and production dynamics among the species as they are visited by different pollinator guilds (see above).

The species studied included: I. alba (subgen. Quamoclit) with long, white, hawk-moth-pollinated flowers (McDonald, 1991), I. rubriflora (subgen. Quamoclit) with medium-sized, red, allegedly hummingbird-pollinated flowers (cf. Wilson, 1960; Austin, 1975) and I. cairica (subgen. Quamoclit) with violet-pink flowers, I. hieronymi var. hieronymi (subgen. Eriospermum) with pink flowers, I. indica (subgen. Ipomoea) with blue flowers and I. purpurea (subgen. Ipomoea) with pink, white, or purple flowers, all bee-pollinated (Real, 1981; Maimoni-Rodella et al., 1982; Maimoni-Rodella and Rodella, 1992; Pinheiro and Schlindwein, 1998; Galetto et al., 2002). Ipomoea rubriflora and I. hieronymi are endemic to Bolivia and Argentina (Chiarini and Ariza Espinar, 2004), whereas the other species are mainly pantropical (Austin and Huáman, 1996; Chiarini and Ariza Espinar, 2004). Regarding their breeding system, some species are self-compatible (SC), such as I. alba (Martin, 1970), I. purpurea (Chang and Rausher, 1999; Galetto et al., 2002), and I. rubriflora (L. Galetto, unpubl. res.), whereas others are self-incompatible (SI), such as I. hieronymi (L. Galetto, unpubl. res.), I. indica (Martin, 1970), and I. cairica (Maimoni-Rodella et al., 1982; Pinheiro and Schlindwein, 1998; Laporta and Suyama, 2002).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The source of the populations studied for each analysis is given in Table 1. In each population three to five individuals were sampled.

Table 1.

Species and study sites for Ipomoea populations from Argentina, Prov. Córdoba

| Species |

Population |

Flower colour |

Localities and dates of study |

Voucher |

Data taken |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. alba L. | 1 | White | Dept Capital, Barrio Cofico, January 13, 1996. | Bernardello & Galetto 890 | Nectar, pollinators |

| 2 | White | Dept. Capital, Barrio Cerro de las Rosas, December 12, 1987. | Galetto & Bernardello 10 | Nectar chemistry, nectary, pollinators | |

| 3 | White | Dept. Capital, Argüello, February 22, 1989. | Galetto & Bernardello 49 | Nectar chemistry, pollinators | |

| I. cairica (L.) Sweet | 1 | Violet-pink | Dept. Colón, Villa Allende, November 11, 1987. | Galetto & Bernardello 8 | Nectar chemistry, nectary, pollinators |

| 2 | Violet-pink | Dept. Colón, El Diquecito, November 21, 1987. | Galetto & Bernardello 3 | Nectar chemistry, pollinators | |

| 3 | Violet-pink | Dept. Colón, La Quebrada, October 26, 1989. | Galetto w.n. | Nectar chemistry, pollinators | |

| 4 | Violet-pink | Dept. Colón, Río Carnero, February 13, 1993. | Galetto w.n. | Nectar, pollinators | |

| 5 | Violet-pink | Dept. Colón, Río Ceballos, 20 Dec. 1991. | Galetto w.n. | Nectar chemistry | |

| I. hieronymi (O.K.) O'Donell var. hieronymi | 1 | Pink | Dept. Capital, Villa Warcalde, 30 Dec. 1988. | Galetto 38 | Nectar chemistry, nectary, pollinators |

| 2 | Pink | Dept. Santa María, Los Aromos, 29 Dec. 1996 | Galetto 717 | Nectar, pollinators | |

| I. indica (Burm. f.) Merr. | 1 | Blue | Dept San Justo, Miramar, 24 May 1995 | Galetto & Bernardello 322 | Nectar secretion, pollinators |

| 2 | Blue | Dept Capital, Villa Warcalde, 30 Dec. 1988 | Galetto & Bernardello 40 | Nectar chemistry, nectary, pollinators | |

| 3 | Blue | Dept Capital, Barrio Escobar, 19 Dec. 1987 | Galetto & Bernardello 11 | Nectar chemistry, pollinators | |

| 4 | Blue | Dept Capital, Cerro de Las Rosas, 21 Dec. 1988 | Galetto & Bernardello 35 | Nectar chemistry | |

| I. purpurea (L.) Roth | 1 | Purple | Dept Santa María, La Serranita, 7 Feb. 1997 | Galetto 671 | Nectar, pollinators |

| 2 | Pink | Dept Capital, Córdoba, 8 June 1997 | Galetto 725 | Nectar, pollinators | |

| 3 | Purple | Dept Capital, Córdoba, 8 June 1997 | Galetto 726 | Nectar, pollinators | |

| 4 | White | Dept Capital, Barrio Escobar, 5 Apr. 1988 | Galetto & Bernardello 12 | Nectar chemistry, nectary | |

| 5 | Purple | Dept Capital, Barrio Escobar, 7 Apr. 1988 | Galetto & Bernardello 13 | Nectar chemistry, pollinators | |

| I. rubriflora O'Donell | 1 | Red | Dept Punilla, Carlos Paz, 22 Mar. 1989 | Galetto 52 | Nectar chemistry, nectary |

| 2 | Red | Dept Santa María, La Serranita, 16 Mar. 1997 | Galetto 714 | Nectar secretion and chemistry | |

| 3 | Red | Dept Colón, Río Carnero,13 Feb. 1993 | Galetto w.n. | Nectar secretion and chemistry |

Vouchers are deposited at CORD (Museo Botanico de Córdoba).

w.n., Without number.

In each population studied, flower visitors were recorded on individual plants at the middle of the lifetime of the flower, for 15 min on three different days.

To analyse nectary structure, flowers were fixed in 70 % ethanol, dehydrated in an ethyl alcohol–xylol series, and embedded in Paraplast. Cross- and longitudinal sections were cut at 10 µm, mounted serially, stained with safranin– astral blue (Maacz and Vagas, 1961), and observed with a compound microscope at ×100–1000 magnifications. To detect stomata in the nectariferous tissue, glands were cleared with standard bleach for 1 min and stained with Lugol solution (I2/IK). Photomicrographs were taken with Kodak T-Max film, 100 ASA, with an Axiophot-photomicrographic system equipped with automatic exposure.

Flower length, excluding the pedicel, was measured (n = 10 flowers per species). Nectary tissue volume was calculated with the non-circular section toroids' formula: V = 2πsr, where s = nectary sectional area and r = nectary radius measured from the sections' centre of gravity (n = 4 flowers per species). This parameter was estimated with reference to the weight of the drawings of the nectary in longitudinal section (the two stained areas at the ovary base). The drawings were made on a homogeneous paper using a camera lucida fitted on a stereomicroscope.

Ovaries for observation under a scanning electron microscope (SEM) were dehydrated in an acetone series and dried using CO2 in a critical-point dryer (Balzers, Switzerland). Dried samples were mounted and then gold-coated to a thickness of 25 nm (Balzers). Photomicrographs were taken with a Jeol 35CF scanning electron Photomicroscope on AgfaPan APX 100.

In the field, nectar drops for each sample were placed in 1 mL vials and quickly frozen. Sugar concentration and nectar volume were measured in the field with an Atago pocket refractometer and graduated capillary glass tubes, respectively. Tests following Baker and Baker (1975) for amino acids, lipids, phenols, alkaloids and reducing acids were made on nectar spots on chromatography paper. The ‘histidine scale’ (Baker and Baker, 1975) was used to quantify amino acids. Sugars were identified via gas chromatography. Nectar was lyophilized and silylated according to Sweeley et al. (1963). The derivatives were then injected into a Konik KNK 3000-HRGS gas chromatograph equipped with a Spectra-Physics SP 4290 data integrator, a flame ionization detector and an OV 101 column (2 m long and 3 mm diameter, on 3 % Chromosorb G/AW-DMCS mesh 100–120). Nitrogen was the carrier gas and the following temperature programme was used: 208 °C/2 min, 1 °C/min until 215 °C, 8 °C/min until 280 °C for 5 min. Carbohydrate standards (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA) were prepared using the same method. Chromatographic sugar analyses were run at least twice for each sample. Sugar ratios, r = sucrose [S] : (fructose [F] + glucose [G]), and hexose ratios, h = G : F, were calculated as per Baker and Baker (1983b).

Floral longevity was determined in ten bagged flowers by following the flowers' development until the corollas began to wilt. Randomly chosen flowers in the bud stage were bagged using paper bags to prevent pollinator visits and were tagged for identification. Nectar production was determined by using flower sets of seven to 20 flowers each according to flower availability. Flowers of a set were assigned from different individuals (one to four per each plant according to the availability of plants). The sampling schedule took into account the lifetime of the flower of each species, with either four or five flower sets (Table 4). Data were taken once for each set, allowing the nectar to accumulate until it was measured. Net nectar production rate (NPR) per hour was calculated as: mg of sugar produced between measurements/number of hours between them (mg h−1).

Table 4.

Nectar sugar concentration (% of sucrose, wt/wt), nectar volume (µL), and mg of sugar of six Argentinian Ipomoea species measured in flower sets subjected to different removal schedules throughout the lifetime of the flower

| (a) I. alba (each flower set n = 10) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of sampling (hours after flower opening) |

||||||||||||

| 2000 (1) |

2300 (4) |

0200 (7) |

0500 (10) |

0800 (13) |

Total amount of sugar per flower (mg) |

|||||||

| Set 1 | ||||||||||||

| Conc. | 35·14 ± 1·63 | 6·42 ± 2·76 | 19·00 ± 3·26 | 14·42 ± 1·81 | 13·50 ± 3·90 | 17·31 ± 5·65 | ||||||

| Volume | 10·28 ± 1·57 | 31·14 ± 16·0 | 9·85 ± 3·23 | 11·85 ± 13·7 | 13·50 ± 3·90 | |||||||

| mg sugar | 3·98 ± 0·58 | 9·22 ± 4·74 | 1·98 ± 0·67 | 1·81 ± 2·22 | 0·32 ± 0·29 | |||||||

| Set 2 | ||||||||||||

| Conc. | 36·14 ± 0·75 | 28·07 ± 1·30 | 21·21 ± 1·82 | 17·14 ± 2·26 | 21·06 ± 4·94 | |||||||

| Volume | 31·42 ± 0·69 | 17·42 ± 9·10 | 4·64 ± 1·18 | 8·71 ± 10·87 | ||||||||

| mg sugar | 13·06 ± 5·30 | 5·49 ± 2·79 | 1·09 ± 0·35 | 1·41 ± 1·86 | ||||||||

| Set 3 | ||||||||||||

| Conc. | 34·42 ± 1·94 | 27·85 ± 2·54 | 23·07 ± 2·49 | 22·15 ± 7·80 | ||||||||

| Volume | 46·28 ± 1·90 | 11·42 ± 13·9 | 3·14 ± 0·89 | |||||||||

| mg sugar | 17·88 ± 5·07 | 3·45 ± 3·96 | 0·81 ± 0·24 | |||||||||

| Set 4 | ||||||||||||

| Conc. | 34·14 ± 1·87 | 25·35 ± 2·71 | 17·69 ± 3·76 | |||||||||

| Volume | 43·71 ± 1·75 | 3·00 ± 0·57 | ||||||||||

| mg sugar | 16·84 ± 3·87 | 0·84 ± 0·19 | ||||||||||

| Set 5 (control) | ||||||||||||

| Conc. | 31·06 ± 2·02 | 19·41 ± 4·30 | ||||||||||

| Volume | 50·12 ± 2·02 | |||||||||||

| mg sugar | 19·41 ± 4·30 | |||||||||||

| (b) I. cairica (each flower set n = 7) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of sampling (hours after flower opening) |

||||||||||

| 0930 (2) |

1230 (5) |

1430 (7) |

1700 (9·5) |

Total amount of sugar per flower (mg) |

||||||

| Set 1 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 52·10 ± 5·64 | 46·70 ± 3·77 | 28·44 ± 2·60 | 29·33 ± 4·45 | 5·05 ± 0·49a | |||||

| Volume | 1·55 ± 0·43 | 4·70 ± 0·73 | 3·25 ± 1·71 | 0·90 ± 0·99 | ||||||

| mg sugar | 1·00 ± 0·32 | 2·63 ± 0·32 | 1·14 ± 0·39 | 0·29 ± 0·29 | ||||||

| Set 2 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 52·60 ± 5·56 | 35·00 ± 5·92 | 30·87 ± 4·01 | 5·46 ± 0·75a | ||||||

| Volume | 4·20 ± 0·78 | 5·40 ± 1·50 | 1·75 ± 1·11 | |||||||

| mg sugar | 2·72 ± 0·46 | 2·14 ± 0·29 | 0·61 ± 0·39 | |||||||

| Set 3 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 47·60 ± 5·75 | 36·80 ± 3·85 | 3·84 ± 0·65b | |||||||

| Volume | 5·10 ± 1·97 | 2·30 ± 0·92 | ||||||||

| mg sugar | 2·89 ± 1·04 | 0·96 ± 0·35 | ||||||||

| Set 4 (control) | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 44·70 ± 5·39 | 4·18 ± 1·09b | ||||||||

| Volume | 8·00 ± 5·39 | |||||||||

| mg sugar | 4·18 ± 1·09 | |||||||||

| (c) I. hieronymi var. hieronymi (each flower set n = 7) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of sampling (hours after flower opening) |

||||||||||

| 0800 (1) |

1030 (3·5) |

1300 (6) |

1530 (8·5) |

Total amount of sugar per flower (mg) |

||||||

| Set 1 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 34·42 ± 4·45 | 26·31 ± 6·15 | 29·21 ± 4·22 | 22·44 ± 3·59 | 3·13 ± 0·25a | |||||

| Volume | 1·35 ± 0·41 | 1·75 ± 0·74 | 2·81 ± 1·37 | 5·20 ± 1·52 | ||||||

| mg sugar | 0·55 ± 0·24 | 0·50 ± 0·43 | 0·89 ± 0·28 | 1·19 ± 0·37 | ||||||

| Set 2 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 38·14 ± 1·76 | 31·00 ± 4·42 | 28·72 ± 6·66 | 3·00 ± 0·41a | ||||||

| Volume | 2·28 ± 0·67 | 2·14 ± 1·09 | 4·07 ± 0·92 | |||||||

| mg sugar | 1·01 ± 0·30 | 0·69 ± 0·22 | 1·30 ± 0·45 | |||||||

| Set 3 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 37·66 ± 3·07 | 29·55 ± 4·82 | 2·53 ± 0·61a | |||||||

| Volume | 2·70 ± 0·75 | 4·00 ± 1·61 | ||||||||

| mg sugar | 1·19 ± 0·37 | 1·33 ± 0·40 | ||||||||

| Set 4 (control) | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 36·64 ± 4·04 | 5·01 ± 2·11b | ||||||||

| Volume | 12·00 ± 5·21 | |||||||||

| mg sugar | 5·01 ± 2·11 | |||||||||

| (d) I. indica (each flower set n = 10) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of sampling (hours after flower opening) |

||||||||||||

| 0800 (1) |

1100 (4) |

1400 (7) |

1700 (10) |

2000 (13) |

Total amount of sugar per flower (mg) |

|||||||

| Set 1 | ||||||||||||

| Conc. | 34·83 ± 2·22 | 34·83 ± 2·22 | 36·33 ± 1·86 | 31·5 ± 2·51 | 23·25 ± 4·03 | 5·47 ± 1·19a | ||||||

| Volume | 3·00 ± 0·63 | 4·33 ± 0·2 | 3·33 ± 1·03 | 2·41 ± 2·06 | 0·75 ± 0·75 | |||||||

| mg sugar | 1·21 ± 0·30 | 1·73 ± 0·34 | 1·44 ± 0·47 | 0·89 ± 0·79 | 0·20 ± 0·23 | |||||||

| Set 2 | ||||||||||||

| Conc. | 38·50 ± 1·51 | 8·16 ± 2·99 | 2·33 ± 2·42 | 8·50 ± 1·22 | 6·07 ± 0·74a | |||||||

| Volume | 5·66 ± 1·51 | 3·33 ± 0·81 | 3·75 ± 0·75 | 2·00 ± 1·09 | ||||||||

| mg sugar | 2·55 ± 0·35 | 1·48 ± 0·35 | 1·40 ± 0·40 | 0·64 ± 0·37 | ||||||||

| Set 3 | ||||||||||||

| Conc. | 39·83 ± 2·04 | 35·16 ± 2·13 | 3·66 ± 4·80 | 5·75 ± 0·79a | ||||||||

| Volume | 6·66 ± 0·81 | 3·66 ± 0·51 | 4·33 ± 3·14 | |||||||||

| mg sugar | 3·11 ± 0·44 | 1·50 ± 0·22 | 1·13 ± 0·79 | |||||||||

| Set 4 | ||||||||||||

| Conc. | 40·00 ± 1·41 | 33·50 ± 2·81 | 4·77 ± 0·85ab | |||||||||

| Volume | 8·00 ± 1·55 | 2·58 ± 0·49 | ||||||||||

| mg sugar | 3·76 ± 0·70 | 1·01 ± 0·22 | ||||||||||

| Set 5 (control) | ||||||||||||

| Conc. | 36·83 ± 1·72 | 3·98 ± 0·69b | ||||||||||

| Volume | 9·33 ± 1·63 | |||||||||||

| mg sugar | 3·98 ± 0·69 | |||||||||||

| (e) I. purpurea (each flower set n = 15) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of sampling (hours after flower opening) |

||||||||||

| 0830 (1) |

1130 (4) |

1430 (7) |

1730 (10) |

Total amount of sugar per flower (mg) |

||||||

| Set 1 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 38·00 ± 4·17 | 25·30 ± 5·50 | – | – | 1·50 ± 0·23a | |||||

| Volume | 2·40 ± 0·45 | 1·30 ± 0·80 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| mg sugar | 1·05 ± 0·15 | 0·45 ± 0·35 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Set 2 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 40·00 ± 1·70 | 23·20 ± 1·6 | – | 1·55 ± 0·62a | ||||||

| Volume | 3·10 ± 0·76 | 0·46 ± 0·32 | 0 | |||||||

| mg sugar | 1·35 ± 0·51 | 0·20 ± 0·21 | 0 | |||||||

| Set 3 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 41·50 ± 6·37 | – | 1·32 ± 0·28a | |||||||

| Volume | 2·85 ± 0·83 | 0 | ||||||||

| mg sugar | 1·32 ± 0·28 | 0 | ||||||||

| Set 4 (control) | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 38·20 ± 7·59 | 1·24 ± 0·12b | ||||||||

| Volume | 2·42 ± 0·82 | |||||||||

| mg sugar | 1·24 ± 0·12 | |||||||||

| (f) I. rubriflora (each flower set n = 20) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of sampling (hours after flower opening) |

||||||||||

| 0830 (1·5) |

1130 (4·5) |

1330 (6·5) |

1530 (8·5) |

Total amount of sugar per flower (mg) |

||||||

| Set 1 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 25·15 ± 2·20 | 19·72 ± 5·51 | – | – | 0·80 ± 0·39 | |||||

| Volume | 2·43 ± 0·88 | 0·64 ± 0·02 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| mg sugar | 0·67 ± 0·27 | 0·13 ± 0·16 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Set 2 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 24·98 ± 2·42 | – | – | 0·90 ± 0·33 | ||||||

| Volume | 3·16 ± 0·99 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| mg sugar | 0·90 ± 0·33 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Set 3 | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 25·17 ± 2·50 | – | 0·88 ± 0·33 | |||||||

| Volume | 3·11 ± 1·12 | 0 | ||||||||

| mg sugar | 0·88 ± 0·33 | 0 | ||||||||

| Set 4 (control) | ||||||||||

| Conc. | 25·42 ± 2·17 | 1·03 ± 0·49 | ||||||||

| Volume | 3·73 ± 1·73 | |||||||||

| mg sugar | 1·03 ± 0·49 | |||||||||

Data on the diagonal (first measurements of each set underlined) correspond to the nectar production dynamics of each species.

The total amount of sugar per flower was calculated for each set using set 4 or 5 as control, according to the species. When statistically significant differences were found, lower-case letters as superscript indicate a posteriori test results.

To evaluate the effect of removal on total sugar amount, nectar was removed and measured from the same flower repeatedly during the entire active secretion period. Nectar was extracted with capillary glass tubes without removing the flowers from the plant, taking extreme care to avoid damage to the nectaries. Sets of seven to 20 flowers were subjected to a different number of removals according to the secretion period of the species. Flowers of a set were assigned from different individuals (one to four per each plant according to the availability of plants). According to the flower lifetime of the species, four or five flower sets were assigned (see Table 4); for the first measurement, nectar was allowed to gather for approx. 1 h because it was not secreted in buds, and an interval of approx. 3 h was left to allow nectar to accumulate between measurements. The general scheme was to allow nectar to accumulate for a determined period (approx. 3, 6, 9, 12 h, according to the set; see Table 4) and then to remove it a number of times: set 1 = five to four nectar removals; set 2 = four to three removals; set 3 = three to two removals; set 4 of the species that have five sets = two removals; set 4 and set 5 (control sets, Table 4) = nectar was allowed to accumulate during the entire flower lifetime and only one measurement was performed. The total amount of sugar per flower was calculated as the product of nectar volume and sugar concentration per unit volume, e.g. mg per µL after Bolten et al. (1979).

Statistical tests were performed using methods described in Sokal and Rohlf (1995) with the SPSS statistical program package (SPSS release 10.0, 1999). All distributions were tested for randomness of nominal data (Runs test), homogeneity of variances (Levene test), and departures from normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnov for goodness-of-fit test). The effects of nectar removal on the total amount of sugar produced by each set of flowers were compared with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and with the Bonferroni's post hoc test for multiple comparisons among pairs of means, to evaluate the consequences of pollinator visits to each species. Regression analyses were done using species means to estimate if flower traits are explained by the increase of flower size. The relationship between pollination guilds and nectar traits was assessed by qualitative comparisons because of the low number of hummingbird and hawk-moth species.

RESULTS

Floral visitors

Hymenopterans were regular visitors of I. cairica, I. hieronymi, I. indica and I. purpurea (Table 2). The introduced European bee (Apis mellifera) was occasionally observed on the study species, but most visits corresponded to native bees from the families Apidae (Bombus opifex, B. morio), Megachilidae (Megachile sp.), Anthophoridae (Centris sp., Thygater sp.) and Halictidae (Anglochloropsis sp.) (Table 2). In the populations of I. cairica and I. purpurea studied, both Bombus species were more frequent visitors than the other bees. On the other hand, hummingbirds [Trochilidae, both sexes of Chlorostilbon aureoventris and females of Sappho sparganura] were the most frequent visitors of I. rubriflora and sphingids (Sphingidae: Manduca sp. and Agrius cingulata] of I. alba (Table 2).

Table 2.

Flower visitors of Argentinian Ipomoea species

| Species |

Hymenopterans |

Hummingbirds |

Sphingids |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. alba | – | – | Sphingidae: Manduca sp. ***, Agrius cingulata*** |

| I. cairica | Apidae: Bombus opifex***, B. morio***, Apis mellifera* | – | – |

| Megachilidae: Megachile sp.** | |||

| Anthophoridae: Centris sp.**, Thygater sp.** | |||

| Halictidae: Anglochloropsis sp.** | |||

| I. hieronymi | Apidae: Bombus opifex*, B. morio* | – | – |

| Megachilidae: Megachile sp.** | |||

| Anthophoridae: Centris sp.*, Melitoma sp.***, Thygater sp.*** | |||

| Halictidae: Anglochloropsis sp.** | |||

| I. indica | Apidae: Bombus opifex*, B. morio***, Apis mellifera* | – | – |

| Anthophoridae: Thygater sp.*** | |||

| Halictidae: Halictus sp.** | |||

| I. purpurea | Apidae: Bombus opifex***, B. morio***, B. bellicosus *, Apis mellifera* | – | – |

| Megachilidae: Megachile sp.** | |||

| Anthophoridae: Thygater sp.**, Ptilothrix sp.* | |||

| Halictidae: Halictus sp.* | |||

| I. rubriflora | Apidae: Bombus opifex* | Trochilidae: Chlorostilbon | – |

| Vespidae: Polystes canadensis* | aureoventiris***, Sappho sparganura*** |

Frequency: *, rare, **, common, ***, very common, –, not recorded.

Floral nectaries

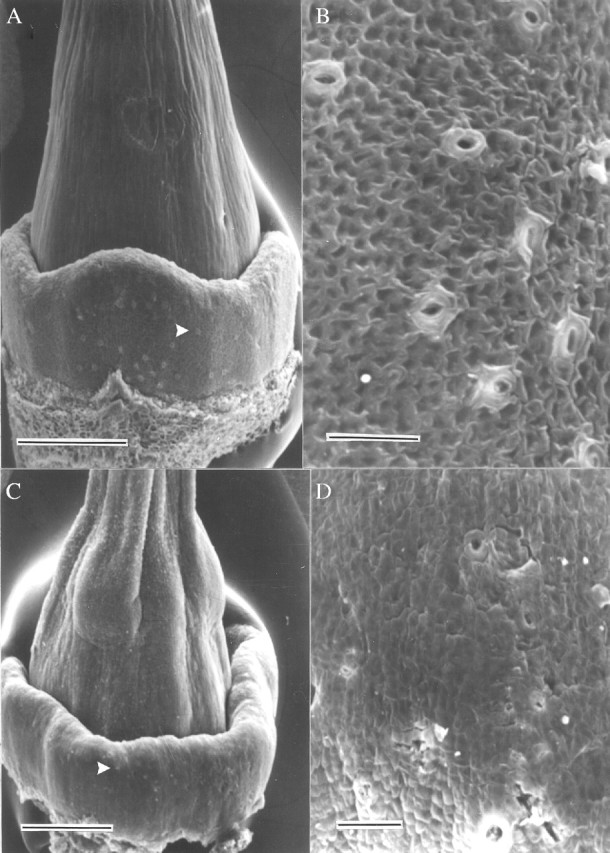

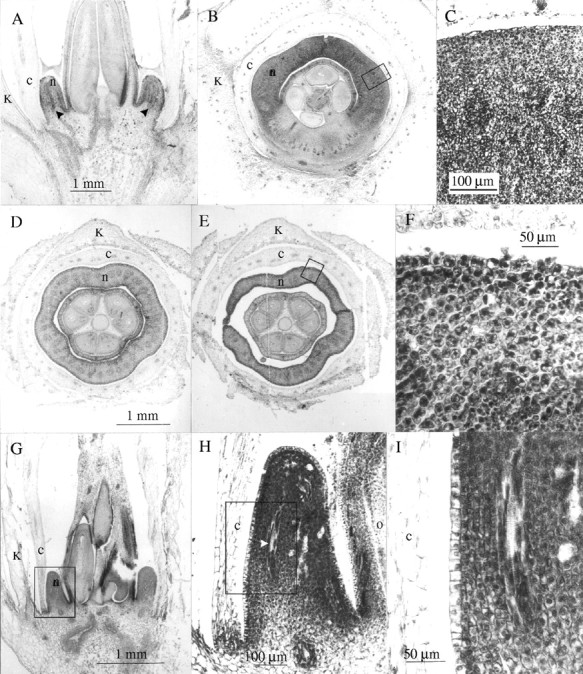

All the species studied had a conspicuous floral (also called nuptial), discoidal nectary surrounding the ovary base (Figs 1A and C; 2A, B, D, E and G). The secretory tissue was composed of intensely stained cells, each with a big nucleus and many small vacuoles (Fig. 2C, F and I), and was supplied by vascular bundles with both xylem and phloem branches (Fig. 2A and H–I). The epithelial cells possessed a cuticle, fewer cellular contents, and generally a big vacuole (Fig. 2I). Numerous, always open, stomata were found on the epidermis of the nectaries (Fig. 1B and D); nectar exudation possibly occurs through them. Their distribution varied according to the species: homogeneously distributed over all the nectary surface (I. indica and I. rubriflora, Fig. 1A and B), in two areas of the nectary: the apex and in the base (I. alba), or exclusively in the apical region (I. cairica, I. hieronymi and I. purpurea; Fig. 1C and D).

Fig. 1.

Nectary SEM photomicrographs: (A and B) Ipomoea rubriflora, (C and D) I. purpurea. (A and C) View of ovary with the nectary surrounding its base; arrow head points to one stoma. (B and D) Detail of the nectary epidermis showing several stomata. Scale bars: A and C = 500 µm; B and D = 50 µm.

Fig. 2.

Optical microscope photomicrographs showing nectary structure: (A–C) Ipomoea hieronymi; (D–F) I. indica; (G–I) I. rubriflora. (A) Flower partial longitudinal section; (B) flower cross-section; (C) detail of the nectariferous tissue indicated in B; (D–E) flower cross-sections at lower and upper levels of the nectary; (F) detail of the nectariferous tissue outlined in E; (G) flower partial longitudinal section; (H) detail of nectary outlined in G; (I) detail of the nectariferous tissue indicated in H. Abbreviations: k, calyx, c, corolla, n, nectary, o, ovary. Arrow heads indicate vascular bundles. A and B at the same scale; D and E at the same scale.

Floral longevity

Flowers lasted less than half a day: from 8–9 h in I. hieronymi, approx. 10 h in I. cairica, I. purpurea and I. rubriflora to approx. 12 h in I. alba and I. indica. With the exception of I. alba, whose flowers opened at twilight and faded at sunset or exceptionally at midday, the remaining species had diurnal anthesis, lasting from early morning to the afternoon.

Nectar chemical composition

Alkaloids, phenols, antioxidants and lipids were never detected. On the other hand, all samples had amino acids and sugars in variable concentrations (Table 3). Amino acids were found in concentrations from 2 to 7 on the histidine scale (Table 3). The three most common sugars were always detected and the proportions found for the different samples of each taxon were, in general, homogeneous with the exception of I. cairica that showed a great intraspecific variability (Table 3). Most species had sucrose-dominant nectars; only I. cairica presented hexose dominant or hexose-rich samples (Table 3). Hexose ratios indicated that most species had more glucose than fructose (Table 3).

Table 3.

Chemical composition of nectar in Ipomoea species

| Sugars (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species |

Population no. |

Sucrose |

Fructose |

Glucose |

r |

hr |

hs |

|

| I. alba | 1 | 87·19 ± 4·84 | 8·78 ± 3·21 | 4·01 ± 2·53 | 6·81 | 0·45 | 5 | |

| 2 | 63·14 ± 2·01 | 20·43 ± 1·84 | 16·42 ± 2·41 | 1·71 | 0·80 | 5 | ||

| 3 | 82·21 ± 3·88 | 13·80 ± 4·24 | 3·98 ± 0·97 | 4·62 | 0·28 | 4 | ||

| Mean | 77·51 ± 12·7 | 14·33 ± 5·84 | 8·13 ± 7·17 | 3·45 | 0·56 | |||

| I. cairica | 2 | 0·52 ± 0·37 | 34·54 ± 2·06 | 64·93 ± 2·42 | 0·005 | 1·87 | 5 | |

| 5 | 35·62 ± 3·34 | 18·81 ± 1·72 | 45·52 ± 2·09 | 0·55 | 2·41 | 6 | ||

| 3 | 0·37 ± 0·30 | 36·52 ± 3·69 | 63·10 ± 3·99 | 0·003 | 1·72 | 2 | ||

| 1 | 0·34 ± 0·23 | 32·33 ± 1·68 | 67·32 ± 2·87 | 0·003 | 2·08 | 5 | ||

| 4 | 15·43 ± 2·12 | 36·86 ± 1·38 | 47·68 ± 0·75 | 0·18 | 1·29 | 4 | ||

| Mean | 10·45 ± 15·5 | 31·81 ± 7·49 | 57·71 ± 10·3 | 0·12 | 1·81 | |||

| I. indica | 4 | 55·74 ± 4·05 | 18·41 ± 3·92 | 25·84 ± 2·13 | 1·25 | 1·40 | 6 | |

| 3 | 50·74 ± 6·71 | 21·12 ± 1·81 | 28·12 ± 4·90 | 1·03 | 1·33 | 7 | ||

| 2 | 54·31 ± 1·89 | 18·81 ± 2·13 | 26·87 ± 1·37 | 1·18 | 1·42 | 7 | ||

| Mean | 53·60 ± 2·58 | 19·45 ± 1·46 | 26·94 ± 1·14 | 1·15 | 1·39 | |||

| I. hieronymi | 2 | 60·39 ± 10·97 | 15·58 ± 6·22 | 24·01 ± 5·25 | 1·52 | 1·54 | 2 | |

| 1 | 65·04 ± 5·76 | 11·03 ± 2·49 | 23·91 ± 3·27 | 1·86 | 2·17 | 2 | ||

| Mean | 62·72 ± 3·28 | 13·31 ± 3·21 | 23·96 ± 0·07 | 1·68 | 1·80 | |||

| I. rubriflora | 2 | 66·08 ± 4·98 | 22·13 ± 5·00 | 11·78 ± 2·52 | 1·94 | 0·53 | 6 | |

| 1 | 64·86 ± 4·57 | 19·17 ± 3·88 | 15·96 ± 2·61 | 1·84 | 0·83 | 6 | ||

| 3 | 62·61 ± 8·93 | 13·95 ± 8·74 | 23·42 ± 4·33 | 1·67 | 1·67 | 5 | ||

| Mean | 64·52 ± 1·76 | 18·42 ± 4·14 | 17·05 ± 5·89 | 1·82 | 0·93 | |||

| I. purpurea | 4 | 68·71 ± 5·07 | 7·48 ± 2·55 | 23·79 ± 2·50 | 2·19 | 3·18 | 3 | |

| 2 | 65·74 ± 7·52 | 14·01 ± 1·67 | 20·24 ± 3·84 | 1·91 | 1·44 | 3 | ||

| 3 | 69·63 ± 6·62 | 8·96 ± 4·00 | 21·41 ± 2·93 | 2·29 | 2·38 | 5 | ||

| 1 | 78·68 ± 2·00 | 10·27 ± 0·85 | 11·04 ± 1·14 | 3·69 | 1·07 | 5 | ||

| 5 | 60·08 ± 5·51 | 15·88 ± 3·37 | 24·03 ± 4·07 | 1·50 | 1·51 | 4 | ||

| Mean | 68·57 ± 6·77 | 11·32 ± 3·52 | 20·10 ± 5·31 | 2·18 | 1·78 | |||

Values are means ± s.d.

r, Sugar ratio; hr, hexose ratio; hs, histidine scale.

Population nos corresponds to those in Table 1 and the number of individuals sampled for each one was four.

Nectar production dynamics

Nectar traits varied among the different species examined, but was quite constant for each one. Most species had a mean nectar sugar concentration thoughout the flower lifetime ranging from 34·28 to 39·42 % (I. alba: x̅ = 34·28 % ± 1·68, I. hieronymi: x̅ = 36·71 % ± 1·65, I. indica: x̅ = 37·99 % ± 2·18, I. purpurea: x̅ = 39·42 % ± 1·42). Extreme values were recorded for I. cairica with the most concentrated nectar (x̅ = 49·25 % ± 3·27), whereas I. rubriflora had the most dilute (x̅ = 25·18 % ± 0·16). Total nectar volume of unvisited flowers ranged from 50·12 µL in I. alba to 2·42 µL in I. purpurea.

In none of the species did the buds secrete nectar. Nectar secretion began as soon as the flowers opened and lasted for a few hours, as in I. purpurea and I. rubriflora, or was continuous during the whole flower lifetime in the remaining species (Table 4, underlined data on the diagonal). Ipomoea hieronymi stood out because there was a notable increase of sugar after midday (Table 4). It should be noted that nectar resorption was never detected for the species studied and that I. alba had a cessation period in the second half of the flower lifetime (Table 4). Some differences became evident when comparing the nectar production rate (NPR) between the Ipomoea species: the hawk-moth-pollinated I. alba showed the highest rate (approx. 2·5 mg h−1) during the active secretion period, whereas the hummingbird-pollinated I. rubriflora the lowest rate (approx. 0·15 mg h−1). All the bee-pollinated species (I. cairica, I. hieronymi, I. indica and I. purpurea) had a similar NPR (approx. 0·4 mg h−1).

Nectar removal effects

Independently of the effect of removing nectar on total sugar production, I. purpurea and I. rubriflora ceased to secrete nectar after a few hours, whereas the remaining species continued until the end of the flower lifetime (Table 4). After nectar removal, species showed different responses in terms of total nectar sugar produced (Table 4). In I. hieronymi, the total amount of nectar produced by flower sets subjected to removals was lower than control sets (F3,44 = 12·53, P = 0·001; Table 4), i.e. there was an inhibition of nectar sugar production. On the other hand, there was an increase in nectar sugar production in I. cairica, I. indica and I. purpurea after removals (F3,39 = 13·52, P = 0·001; F4,29 = 5·57, P = 0·002 and F3,79 = 2·77,P = 0·05, F3,39 = 4·32, P = 0·01, respectively; Table 4), whereas in I. alba and I. rubriflora removals had no effect on total nectar sugar production (F4,35 = 1·04, P = 0·40, and F3,79 = 1·42, P = 0·28, respectively; Table 4).

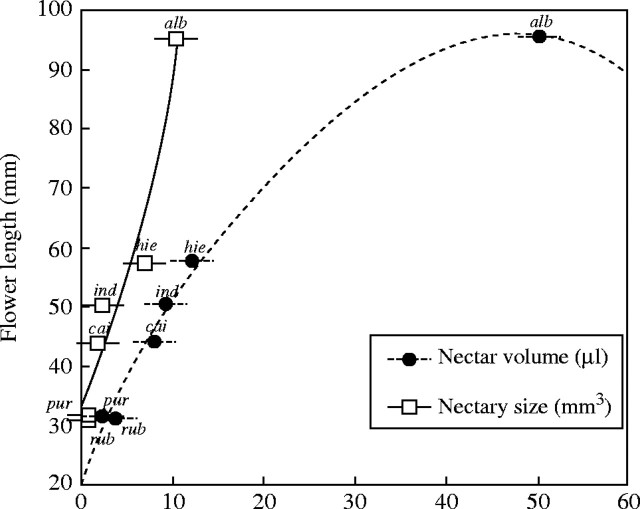

Regressions between flower traits and total nectar volume

Ipomoea alba with longer flower tubes correspondingly had the highest mean total nectar volume per flower and nectary volume (Fig. 3). In the remaining taxa, total volume ranged from x̅ = 2·7 µL in I. purpurea to x̅ = 12·0 µL in I. hieronymi, whereas nectary size ranged from x̅ = 0·6 mm3 ± 0·3 in I. rubriflora to x̅ = 6·9 mm3 ± 1·1 in I. hieronymi (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Quadratic regressions between flower length and nectar volume and nectary size in six Argentinian species of Ipomoea. Plotted values represent the arithmetic mean of each species (abbreviated species' names are shown).

Significant positive regressions were found indicating an increase among three parameters: the longer the flower, the more voluminous the nectary and the higher the nectar volume secreted (R2 = 0·92, P = 0·02, R2 = 0·99, P < 0·0001, respectively; Fig. 3). The number of stomata was not significantly correlated with nectary size and nectar volume (R2 = 0·25, P = 0·65; R2 = 0·45, P = 0·44, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The morphology and location of the nectaries found in the Ipomoea species studied follow the general pattern known for other representatives of the genus (e.g. Fahn, 1979; Stucky and Beckmann, 1982; Pinheiro and Schlindwein, 1998) and seems to be a conservative character for the family (Cronquist, 1981).

Studing nectar may help to determine taxonomic affinities of the species concerned and on the adaptation to the pollinators that visit the taxa. The six Ipomoea species analysed included a wide range of floral colours and visitors, a common feature for the whole genus (e.g. van der Pijl, 1954; Vogel, 1954; Schlising, 1970; Sobreira-Machado and Sazima, 1987; McDonald, 1991). Accordingly, differences in nectar features are to be expected, as found here. However, the differences found could not be related to the pollinator guild of the plants; only the hawk-moth-pollinated I. alba is typical for having higher nectar volume, as previously reported (e.g. Cruden et al., 1983; Opler, 1983). Thus, generalizations for nectar traits and pollinator relationships are precluded in these Ipomoea species.

Nectar secretion can be evaluated with regard to volume or milligrams of sugar, or both. Some authors have studied the effect of nectar removal only considering volume data and found that plants modify secretion as a function of the removals (e.g. Zimmerman and Pyke, 1986). Volume data are not enough to characterize flower costs of nectar secretion (nectar sugar production is more costly to the plant compared with water). Thus, if the sugar production is not known it is impossible to evaluate both the costs of secretion and the energetic reward value for the pollinators.

Concerning the nectar sugar composition, only I. cairica had hexose-predominant nectar, a composition preferred by short-tongued bees (Baker and Baker, 1983a). Regardless of the pollinator, almost all species had a sucrose-dominant nectar. This is an unusual result for bee-pollinated species, which commonly have hexose predominant nectars (Baker and Baker, 1983a; Galetto and Bernardello, 2003). Hummingbird-pollinated flowers tend to have sucrose-dominant nectar (e.g. Baker and Baker, 1983a; Freeman et al., 1985; Stiles and Freeman, 1993), which is confirmed for I. rubriflora among the climbers studied. Thus, no generalization regarding sugar composition and pollinator preference can be shown.

Several authors have found that taxonomically related plants showed a similar trend in their nectar sugar composition because they share common ancestors, rather than because they share the same floral visitors (e.g. Elisens and Freeman, 1988; van Wyk, 1993; Galetto et al. 1998; Perret et al., 2001; Torres and Galetto, 2002). In Ipomoea, two extreme trends related to nectar sugar composition were observed, hexose or sucrose predominant, but they cannot be related to the pollinators or to phylogenetic constraints; however, considering the high number of species in the genus and the scarcity of taxa studied, more data are needed to understand the significance of these results.

Differences were also found among the Ipomoea species studied here in terms of nectar production dynamics. Most of them secreted nectar continuously during the whole lifetime of the flower, whereas I. purpurea and I. rubriflora (the species that has the smallest quantity of nectar per flower) secreted most of it during the first hour of the flower lifetime. Previous data on a few other Ipomoea species, although scant, agree on the whole with the findings reported here (Real, 1981; Stucky and Beckmann, 1982; Devall and Thien, 1989). In particular, I. batatas (Real, 1981) showed similar production dynamics to I. hieronymi studied here. In contrast, in I. pandurata (Stucky and Beckmann, 1982) nectar began to be secreted in the bud and had a comparatively large total volume for a bee-pollinated plant (cf. Opler, 1983). Nevertheless, nectar production dynamics and removal effects, together with sugar composition, could not be clearly related either to the pollinator guild or the breeding system of the species involved. The SI species are all bee-pollinated (I. hieronymi, I. indica, I. cairica) and showed a similar total nectar production, but had differences in their nectar composition (I. hieronymi and I. indica are sucrose-dominant, whereas I. cairica is hexose-dominant). The SC species (I. alba, I. purpurea, I. rubriflora) showed no variation in nectar composition (sucrose-dominant nectars), but significant differences in their nectar production pattern.

In contrast, flower length was associated with both nectary size and total amount of nectar produced. Recent studies suggest that flower morphology is evolutionarily more labile and that corolla traits can frequently change (e.g. Cubas et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 1999) in comparison to changes in the nectar features (e.g. van Wyk, 1993; Galetto et al., 1998; Perret et al., 2001; Torres and Galetto, 2002). The association found here between flower size and total nectar volume secreted in Ipomoea suggests that structural constraints may play a major role in conserving nectar traits, at least in volume.

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous reviewers for useful comments on the manuscript, CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas), ‘Secretaría de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba’, CONICOR (Consejo Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de la Provincia de Córdoba), ‘Agencia Córdoba Ciencia’, and ‘Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica’ for funding, and Cristina Ciarlante for help with the figures. The authors are members of CONICET.

LITERATURE CITED

- Austin DF. 1975. Convolvulaceae. Flora of Panama. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 62: 157–224. [Google Scholar]

- Austin DF, Huáman Z. 1996. A synopsis of Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) in the Americas. Taxon 45: 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Baker HG, Baker I. 1975. Studies of nectar-constitution and pollinator-plant coevolution. In: Gilbert LE, Raven PH, eds. Coevolution of animals and plants. New York: Columbia University Press, 126–152. [Google Scholar]

- Baker HG, Baker I. 1983. A brief historical review of the chemistry of floral nectar. In: Bentley B, Elias TS, eds. The biology of nectaries. New York: Columbia University Press, 126–152. [Google Scholar]

- Baker HG, Baker I. 1983. Floral nectar sugar constituents in relation to pollinator type. In: Jones CE, Little RJ, eds. Handbook of experimental pollination biology. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Baker HG, Baker I. 1990. The predictive value of nectar chemistry to the recognition of pollinator types. Israel Journal of Botany 39: 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardello L, Galetto L, Rodríguez IG. 1994. Reproductive biology, variability of nectar features, and pollination of Combretum fruticosum (Combretaceae) in Argentina. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 114: 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Bolten AB, Feinsinger P, Baker HG, Baker I. 1979. On the calculation of sugar concentration in flower nectar. Oecologia (Berlin) 41: 301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos MC, Wilson P, Thomson JD. 2002. Dynamic nectar replenishment in flowers of Penstemon (Scrophulariaceae). American Journal of Botany 89: 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Rauscher MD. 1999. The role of inbreeding depression in maintaining the mixed mating system of the common morning glory, Ipomoea purpurea Evolution 53: 1366–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini FE, Ariza Espinar L. 2004.Convolvulaceae. Flora Fanerogámica Argentina. Córdoba: Conicet, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cronquist A. 1981.An integrated system of classification of flowering plants. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cruden RW, Hermann SM, Peterson S. 1983. Patterns of nectar production and plant-pollinator coevolution. In Bentley B, Elias TS, eds. The biology of nectaries. New York: Columbia University Press, 80–125. [Google Scholar]

- Cubas P, Vincent C, Coen E. 1999. An epigenetic mutation responsible for natural variation in floral symmetry. Nature 401: 157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devall MS, Thien LB. 1989. Factors influencing the reproductive success of Ipomoea pes-caprae (Convulvulaceae) around the gulf of Mexico. American Journal of Botany 76: 1821–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Elias TS. 1983. Extrafloral nectaries: their structure and distribution. In: Bentley B, Elias TS, eds. The biology of nectaries. New York: Columbia Universtiy Press, 174–203. [Google Scholar]

- Elisens W, Freeman CE. 1988. Floral nectar sugar composition and pollinator type among new genera in tribe Antirrhineae (Scrophulariaceae). American Journal of Botany 75: 971–978. [Google Scholar]

- Fahn A. 1979.Secretory tissues in plants. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feinsinger P. 1978. Ecological interactions between plants and hummingbirds in a successional tropical community. Ecological Monographs 6: 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman CE, Worthington RD, Corral RD. 1985. Some floral nectar-sugar compositions from Durango and Sinaloa, Mexico. Biotropica 17: 309–313. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman CE, Worthington RD, Jackson MS. 1991. Floral nectar sugar compositions of some South and Southeast Asian species. Biotropica 23: 568–574. [Google Scholar]

- Galetto L, Bernardello G. 1995. Characteristics of nectar secretion by Lycium cestroides, L. ciliatum (Solanaceae) and their hybrid. Plant Species Biology 11: 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Galetto L, Bernardello G. 2003. Nectar sugar composition in angiosperms from Chaco and Patagonia (Argentina): an animal visitor's matter? Plant Systematics and Evolution 238: 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Galetto L, Bernardello L. 1992. Nectar secretion pattern and removal effects in six Argentinean Pitcairnioideae (Bromeliaceae). Botanica Acta 105: 292–299. [Google Scholar]

- Galetto L, Bernardello L. 1993. Nectar secretion pattern and removal effects in three Solanaceae. Canadian Journal of Botany 71: 1394–1398. [Google Scholar]

- Galetto L, Bernardello G, Isele IC, Vesprini J, Speroni G, Berduc A. 2000. Reproductive biology of Erythrina crista-galli (Fabaceae). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 87: 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Galetto L, Bernardello G, Rivera G. 1997. Nectar, nectaries, flower visitors, and breeding system in some Argentinean Orchidaceae. Journal of Plant Research 110: 393–403. [Google Scholar]

- Galetto L, Bernardello G, Sosa CA. 1998. The relationship between floral nectar composition and visitors in Lycium (Solanaceae) from Argentina and Chile: what does it reflect?. Flora 193: 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Galetto L, Fioni A, Calviño A. 2002. Exito reproductivo y calidad de los frutos en poblaciones del extremo sur de la distribución de Ipomoea purpurea (Convulvulaceae). Darwiniana 40: 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison CJ, Möller M, Cronk QCB. 1999. Evolution and development of floral diversity in Streptocarpus and Saintpaulia Annals of Botany 84: 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Keeler KH. 1977. The extrafloral nectaries of Ipomoea carnea (Convolvulaceae). American Journal of Botany 64: 1182–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Keeler KH. 1980. The extrafloral nectaries of Ipomoea leptophylla (Convolvulaceae). American Journal of Botany 67: 216–222. [Google Scholar]

- Keeler KH, Kaul RB. 1984. Distribution of defense nectaries in Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae). American Journal of Botany 71: 1364–1372. [Google Scholar]

- Laporta C, Suyama A. 2002. Contribución a la biología de la polinización de Ipomoea cairica (Convolvulaceae). Arnaldoa 9: 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Maacz CJ, Vagas E. 1961. A new method of cellulose and lignified cell walls. Mikroscopie 16: 40–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimoni-Rodella RCS, Rodella RA. 1992. Biologia floral de Ipomoea acuminata Roem. et Schult. (Convolvulaceae). Revista Brasileira de Botânica 15: 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Maimoni-Rodella RCS, Rodella RA, Amaral A, Yanagizawa Y. 1982. Polinizaçao em Ipomoea cairica (L.) Sweet. (Convolvulaceae). Naturalia 7: 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. 1991. Origin and diversity of Mexican Convolvulaceae. Anales del Instituto de Biología de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Botánica 62: 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Martin FW. 1970. Self- and interspecific incompatibility in the Convolvulaceae. Botanical Gazette 131: 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez del Río C. 1990. Sugar preferences in hummingbirds: the influence of subtle chemical differences on food choice. Condor 92: 1022–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Opler P. 1983. Nectar production in a tropical ecosystem. In: Bentley B, Elias TS, eds. The biology of nectaries. New York: Columbia University Press, 30–79. [Google Scholar]

- Perret M, Chautems A, Spichiger R, Peixoto M, SavolainenV. 2001. Nectar sugar composition in relation to pollination syndromes in Sinningieae (Gesneriaceae). Annals of Botany 87: 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pijl L. 1954.Xylocopa and flowers in the tropics. II. Observations on Thunbergia, Ipomoea, Costus, Centrosema and Canavalia Proceedings of the Royal Academy of Sciences 57: 541–551. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro M, Schlindwein C. 1998. A câmara nectarífera de Ipomoea cairica (Convolvulaceae) e abelhas de glossa longa como polinizadores eficientes. Iheringia, Botânica 51: 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor M, Yeo P, Lack A. 1996.The natural history of pollination. Portland, OH: Timber Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pyke GH. 1991. What does it cost a plant to produce floral nectar? Nature 350: 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Pyke GH, Waser NM. 1981. The production of dilute nectars by hummingbird and honeyeater flowers. Biotropica 13: 260–270. [Google Scholar]

- Real L. 1981. Nectar availability and bee-foraging on Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae). Biotropica 13 (Reproductive Botany): 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Schlising RA. 1970. Sequence and timing of bee foraging in flowers of Ipomoea and Aniseia (Convolvulaceae). Ecology 51: 1061–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Sobreira-Machado IS, Sazima M. 1987. Estudo comparativo da biologia floral em duas espécies invasoras: Ipomoea hederifolia and I. quamoclit (Convolvulaceae). Revista Brasileira de Biologia 47: 425–436. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. 1995.Biometry. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Southwick EE. 1990. Floral nectar. American Bee Journal 130: 517–519. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS. 1999.Application guide. Chicago: SPSS Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles FG, Freeman CE. 1993. Patterns in floral nectar characteristics of some bird-visited plant species from Costa Rica. Biotropica 25: 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg MR, Johnsen PB. 1990. Hummingbird sweetness preferences: taste or viscosity? Condor 92: 606–612. [Google Scholar]

- Stucky JM. 1984. Forager attraction by sympatric Ipomoea heredacea and I. purpurea (Convolvulaceae) and corresponding forager behavior and energetics. American Journal of Botany 71: 1237–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Stucky JM, Beckman RL. 1982. pollination biology, self-compatibility, and sterility in Ipomoea pandurata (L.) G. F. W. Meyer (Convolvulaceae). American Journal of Botany 69: 1022–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland SD, Vickery RK. 1993. On the relative importance of floral color, shape and nectar rewards in attracting pollinators to Mimulus Great Basin Naturalist 53: 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeley EC, Bentley R, Makita M, Wells WW. 1963. Gas liquid chromatography of trimethylsilyl derivatives of sugars and related substances. Journal of the American Chemical Society 85: 2497–2507. [Google Scholar]

- Torres C, Galetto L. 2002. Are nectar sugar composition and corolla tube length related to the diversity of insects that visit Asteraceae flowers? Plant Biology 4: 360–366. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel S. 1954.Blütenbiologische Typen als Elemente der Sippengliederung. Jena: Fischer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KA. 1960. The genera of Convolvulaceae in the Southeastern United States. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 41: 298–317. [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk BE. 1993. Nectar sugar composition in southern African Papilionoideae (Fabaceae). Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 21: 271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Pyke GH. 1986. Reproduction in Polemonium: patterns and implication of floral nectar production and standing crops. American Journal of Botany 73: 1405–1415. [Google Scholar]