Abstract

• Background and Aims Estimates of the amount of nuclear DNA of Arabidopsis thaliana, known to be among the lowest within angiosperms, vary considerably. This study aimed to determine genome size of a range of accessions from throughout the entire Eurasian range of the species.

• Methods Twenty accessions from all over Europe and one from Japan were examined using flow cytometry.

• Key Results Significant differences in mean C‐values were detected over a 1·1‐fold range. Mean haploid (1C) genome size was 0·215 pg (211 Mbp) for all analysed accessions. Two accessions were tetraploid.

• Conclusions A closer investigation of the DNA fractions involved in intraspecific genome size differences in this experimentally accessible species may provide information on the factors involved in stability and evolution of genome sizes.

Key words: Arabidopsis thaliana, genome size, flow cytometry, tetraploid, geographic correlation, C‐value, intraspecific variation

INTRODUCTION

Since Arabidopsis thaliana is believed to possess one of the smallest nuclear genomes among higher plants, the exact determination of the genome size has received much attention. Different techniques have been used to estimate the genome size, among them reassociation kinetics (Leutwiler et al., 1984), quantitative gel blot hybridization (Francis et al., 1990), Feulgen photometry (Bennett and Smith, 1991; Krisai and Greilhuber, 1997) and flow cytometry (Arumuganathan and Earle, 1991; Galbraith et al., 1991; Marie and Brown, 1993; Dolezel et al., 1998; Barow and Meister, 2002; Bennett et al., 2003).

Previous studies have estimated the haploid genome size (1C‐value) at between 0·051 pg (Francis et al., 1990, from Bennett et al., 2003) and 0·215 pg (Dolezel et al., 1998, laboratory 1). Sequencing studies found about 125 Mbp (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000), which corresponds to 0·128 pg. Determinations based on reassociation kinetics and quantitative gel blot hybridization tend to suggest smaller genome sizes (0·051–0·082 pg; Leutwiler et al., 1984; Francis et al., 1990) than Feulgen photometry or flow cytometry (0·085–0·215 pg; Galbraith et al., 1991; Dolezel et al., 1998). Furthermore, older studies tend to have estimated lower values than more recent ones.

With regard to the small 1C‐value, the role of endopolyploidy and its relation to cell size or life‐cycle has been investigated by several authors (e.g. Melaragno et al., 1993; Kondorosi et al., 2000; Beemster et al., 2002; Barow and Meister, 2003). It was found that A. thaliana has a high level of endopolyploidy in nearly all parts of the plant (cotyledon, root, lower leaf stalk, lower leaf, upper stem, upper leaf, flower stalk, sepal, petal; Galbraith et al., 1991; Barow and Meister, 2003).

Most of the investigations of genome size in A. thaliana have made use of the accession ‘Columbia’. There are indications that intraspecific variation exists between accessions, e.g. between ‘Columbia’ and the Cape Verde Islands ecotype ‘Cvi‐0’ (A. Meister, unpubl. res.).

In this study, flow cytometry was used to measure the genome size of 21 accessions from throughout the entire Eurasian range, including newly collected material from Middle Asia, and one accession from Japan. Since intraspecific genome size differences are subject to much critical discussion (e.g. Greilhuber, 1998), an attempt was made to check the results by measuring each accession ten times and repeating this procedure for accessions with especially large and small genome sizes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Twenty‐one accessions were included in this study, of which 18 were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre and three were collected in the wild (Table 1). Plants were grown at 24 °C (16 h day, 8 h night) and pots were not allowed to dry out. Leaves from three to five individuals per accession were used for the determinations. Ten determinations were made per accession. This reduces the assumed standard error ratio of 5 % by a factor of 1/√n, i.e. to 1·6 % for ten determinations and 1·1 % for 20 determinations. Three accessions found to have small (‘Kn‐0’, ‘Köl’) and large (‘Mas’) genome sizes in the first series of determinations were measured a second time with ten repeats.

Table 1.

List of accessions of A. thaliana investigated in this study

| Accession | Location |

| Ag‐0* | Argentat, France |

| Alc‐0* | Alcalá de Henares/Madrid, Spain |

| Chi‐0* | Chisdra, Russia |

| Col* | Columbia, Poland |

| Es‐0* | Espoo, Finland |

| Kent* | Kent, UK |

| Kly‐1† | Kolyvan, Russia |

| Kn‐0* | Kaunas, Lithuania |

| Köl* | Köln, Germany |

| La‐0* | Landsberg/Warthe, Poland |

| Ll‐2* | Llagostera, Spain |

| Mas† | Masljacha, Russia |

| Oph* | Ophain, Belgium |

| Oy‐0* | Oystese, Norway |

| Sah‐0* | Sierra Alhambra, Spain |

| Sha* | Shakdara, Tajikistan |

| Sij‐2† | Sijak, Uzbekistan |

| Stoc* | Stockholm, Sweden |

| Tsu‐0* | Tsu, Japan |

| Wa‐1* | Warschau, Poland |

| Ws* | Wassilewskija/Dnepr, Russia |

* From Notthingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC).

† Collected in the wild.

Preparation and analysis

The protocol of Barow and Meister (2002) was followed in the preparation of the nuclear suspensions and the procedure for analysing the DNA contents. A FACStar PLUS flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San José, CA, USA) equipped with two argon lasers INNOVA 90–5 (Coherent, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used and the data were analysed with the program CellQuest (Becton Dickinson, San José, CA, USA). Nuclear DNA content was estimated by the fluorescence of the nuclei of samples stained with propidium iodide relative to the internal standard Raphanus sativus (2C = 1·38 pg; Dolezel et al., 1998). Usually 10 000 nuclei were measured.

Statistical analysis

Normal distribution and homogeneity of variances of the average genome size per accession were tested with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the Levene test, respectively. As the data had no homogeneity of variances, no variance analysis or parametric tests were used for further computations. Instead, the non‐parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used and calculated comparisons of means were conducted using the Dunn test, which can handle the unequal sample size of ten or 20 determinations per accession. Genome size differences among di‐ and tetraploids were computed with the Mann–Whitney U test.

Correlations between mean genome size, geographic coordinates and seed size parameters were estimated with the Spearman rank correlation. Calculations were made using the programs SPSS 10·0 and SigmaStat (Erkrath, Germany). Geographical coordinates were kindly provided by M. H. Hoffmann (University of Halle, Germany).

RESULTS

Ploidy levels

Of the 21 investigated accessions, 19 were diploid and two tetraploid. The tetraploid accessions ‘Stoc’ and ‘Wa‐1’ were excluded from the correlations of genome size, geographic coordinates and seed parameters so as to determine the effect of genome size independently from that of ploidy.

Differences within accessions

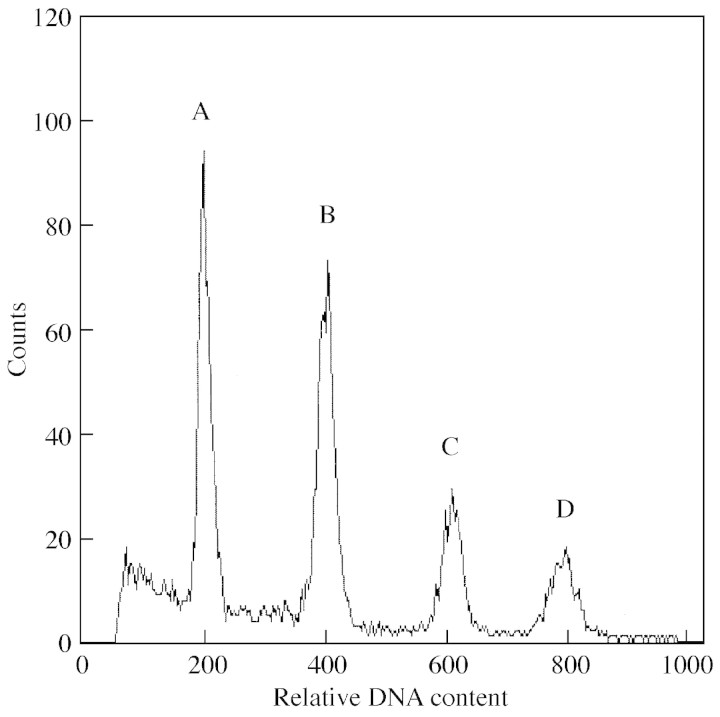

Replicate measurements within accessions were highly repeatable. The standard deviation of genome size in the diploid accessions ranged between 0·004 pg for the accession ‘Ws’ and 0·014 pg for the accession ‘Oy‐0’ (equivalent to 1·04 and 3·26 % of the genome sizes, respectively). The ten replicate measurements of ‘Kn‐0’, ‘Köl’ and ‘Mas’ also varied in this range. An example of a typical flow cytometry histogram is shown in Fig. 1, which also illustrates the high rate of endopolyploidy.

Fig. 1. Flow cytometry histogram of leaf nuclei from the accession ‘Mas’. Peak A corresponds to 2C, peak B to the 4C‐value and peak D to the 8C‐value of A. thaliana. Peak C corresponds to the internal standard, R. sativus.

Differences between diploid accessions

There was a 1·1‐fold difference in genome size between the accessions, with ‘Col’ being the smallest and ‘Kly‐1’ being the largest accession. The mean diploid genome size was 2C = 0·431 pg. A general overview of genome sizes in all the accessions investigated is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean (± standard deviation), minimum and maximum genome sizes of 21 accessions of A. thaliana

| Accession | No. of determinations | Mean (pg) | Minimum (pg) | Maximum (pg) | Significance* |

| Col | 10 | 0·412 ± 0·007 | 0·403 | 0·424 | a |

| Köl | 20 | 0·415 ± 0·012 | 0·390 | 0·437 | a, b |

| Kn‐0 | 20 | 0·421 ± 0·006 | 0·403 | 0·429 | a, b, c, |

| La‐0 | 10 | 0·425 ± 0007 | 0·417 | 0·435 | a, b, c, d |

| Es‐0 | 10 | 0·426 ± 0·009 | 0·411 | 0·439 | a, b, c, d, e |

| Sij‐2 | 10 | 0·429 ± 0·005 | 0·419 | 0·438 | a, b, c, d, e |

| Kent | 10 | 0·429 ± 0·011 | 0·412 | 0·444 | a, b, c, d, e |

| Ll‐2 | 10 | 0·429 ± 0·006 | 0·421 | 0·439 | a, b, c, d, e |

| Tsu | 10 | 0·430 ± 0·007 | 0·421 | 0·443 | a, b, c, d, e |

| Ag‐0 | 10 | 0·432 ± 0·008 | 0·411 | 0·444 | a, b, c, d, e, f |

| Oy‐0 | 10 | 0·436 ± 0·014 | 0·419 | 0·462 | a, b, c, d, e, f |

| Oph | 10 | 0·434 ± 0·010 | 0·419 | 0·445 | a, b, c, d, e, f |

| Chi‐0 | 10 | 0·434 ± 0·008 | 0·416 | 0·446 | b, c, d, e, f |

| Ws | 10 | 0·435 ± 0·004 | 0·427 | 0·441 | c, d, e, f |

| Sha | 10 | 0·439 ± 0·007 | 0·430 | 0·450 | d, e, f |

| Alc‐0 | 10 | 0·440 ± 0·008 | 0·427 | 0·449 | d, e, f |

| Sah‐0 | 10 | 0·441 ± 0·009 | 0·427 | 0·456 | d, e, f |

| Kly‐1 | 10 | 0·450 ± 0·014 | 0·432 | 0·472 | e, f |

| Mas | 20 | 0·448 ± 0·007 | 0·431 | 0·458 | f |

| Stoc | 10 | 0·889 ± 0·031 | 0·856 | 0·942 | |

| Wa‐1 | 10 | 0·892 ± 0·045 | 0·848 | 0·983 |

Differences were calculated for the 19 diploid accessions using the Dunn test.

* Accessions with different letters have significantly different means (P < 0·05).

Genome sizes of the 19 diploid accessions were normally distributed (P = 0·956) but homogeneity of variances was rejected (P = 0·016). Therefore the non‐parametric Kruskal–Wallis test with pairwise comparisons of mean genome size using the Dunn test was used (Table 2). Since this test uses ranks instead of absolute values, differences between accessions are less pronounced than in a parametric test. Despite this weakness of the non‐parametric test, significant differences (P < 0·05) were found between all measurements of the five largest diploids (‘Kly‐1’, ‘Mas’, ‘Sah‐0’, ‘Alc‐0’, ‘Sha’) and the three accessions with the smallest genome sizes (‘Col’, ‘Köl’, ‘Kn‐0’) (Table 2). Accessions with mean genome size differences smaller than that between ‘Chi‐0’ and ‘Col’ are not significantly different from each other. The percentage difference of mean genome size between ‘Chi‐0’ and ‘Col’ is 5·35 %. Thus, significant differences between accessions are larger than the standard deviation within accessions.

Correlation with coordinates and seed parameters

The non‐parametric Spearman test was used to test for correlation of genome size and latitude/longitude. Spearman’s rho resulted in a significant positive correlation between genome size and longitude (ρ = 0·185, P = 0·006, n = 220). This suggests a larger mean genome size of the Eastern accessions compared with the Western accessions within the Eurasian distribution range.

A negative correlation was observed between genome size and latitude for the 19 diploids (ρ = –0·138, P = 0·040, n = 220). Thus, the genome size decreases slightly but significantly with increasing latitude (diploid accessions have a larger genome in the south than in the north).

Seed width and length were measured for 10–50 seeds per accession. Seed length varied between 0·359–0·717 mm with a mean of 0·537 mm, and seed width varied between 0·250–0·543 mm with a mean of 0·334 mm. Spearman’s rho revealed a small but significant negative correlation between genome size and seed width (ρ = –0·095, P = 0·012, n = 700) and genome size and seed length (ρ = –0·099, P < 0·001, n = 700).

Spearman rank correlations between genome size and precipitation or temperature in the vegetative period from October to June revealed no significant correlations (data not shown).

Tetraploid accessions

The two tetraploid accessions ‘Stoc’ and ‘Wa‐1’ had means of 0·889 pg and 0·892 pg, with standard deviations of 0·031 and 0·045 (equivalent to 3·44–5·08 % of the genome size), respectively (Table 2). The 1C DNA amounts of 0·445 pg and 0·446 pg are comparable to those of the 2C‐values of the diploid accessions with large genome sizes.

Rather surprisingly, the length and width of the tetraploid seeds ranged around the upper level of the diploid seeds rather than being noticeably larger, but a Mann–Whitney U test detected significant differences (P < 0·001) between diploid and tetraploid seeds. Seed length varied between 0·542 and 0·696 mm in ‘Wa‐1’ and 0·630 and 0·880 mm in ‘Stoc’, with mean seed lengths of 0·620 mm and 0·708 mm, respectively. Seed width ranged between 0·315 and 0·413 mm in ‘Wa‐1’ and 0·326 and 0·500 mm in ‘Stoc’, with mean seed widths of 0·376 mm and 0·408 mm, respectively. Thus, single seeds from the diploid accessions ‘Oph’ (0·511 mm) and ‘Sij‐2’ (0·543 mm) had larger seed widths than the tetraploid seeds from ‘Wa‐1’ and ‘Stoc’.

DISCUSSION

The 1C‐values given here, estimated using R. sativus (2C = 1·38 pg) as an internal standard, agree with some previously published values (e.g. Galbraith et al., 1991; Dolezel et al., 1998), but are higher than other estimated values [e.g. Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000) or Bennett et al. (2003)]. Differences between these studies might be due to the use of different types of flow cytometers (lamp/laser) (Dolezel et al., 1998), different size standards (Dolezel et al., 1998; Barow and Meister, 2002) or, in the case of sequencing, to a conservative, low estimate of the contribution of centromer regions of the chromosomes of A. thaliana (Bennett et al., 2003).

Bennett et al. (2003) compared the incompletely sequenced A. thaliana genome against the completely sequenced Caenorhabditis elegans genome (1C ≈ 0·1 pg) and determined A. thaliana as 1C ≈ 0·16 pg. Vilhar et al. (2001), using image cytometry with Pisum sativum as the standard (2C = 8·84 pg), estimated similar C‐values for A. thaliana (2C = 0·32 and 0·33 pg). The value used for R. sativus (Dolezel et al., 1998) was derived by a cascade down from Allium cepa (2C = 33·5 pg), in which different laboratories used different flow cytometers and had divergent estimates for A. thaliana.

Nevertheless, since reference was always made to the same internal standard, R. sativus with 1·38 pg (Dolezel et al., 1998, laboratory 1, which was also used for these measurements), the intraspecific variation differences found in this study for accessions of A. thaliana are true.

Measuring accessions from all across the Eurasian range of the species, the Dunn test revealed significant differences. Intraspecific variations of genome size below the species level are supposed to be rare (see review by Greilhuber, 1998). Reported differences can be explained by chromosome polymorphisms and spontaneous aberrations, but also by technical shortcomings (Galbraith et al., 1991; Greilhuber, 1998). Possible measuring errors in the investigations reported here are limited by using the same flow cytometer and at least ten repetitions, which decreases the estimated error from 5 % per measure to 1·6 % (n = 10) or 1·1 % (n = 20) per accession mean. Taking into account the genetic diversity of the accessions found by Schmuths et al. (2004) and the magnitude of the variation in spontaneous aberrations or chromosome polymorphisms found in various angiosperm species (reviewed by Greilhuber, 1998), intraspecific variations in genome size can be expected.

The genome size of the tetraploids ranged between 0·445 and 0·446 pg, which is comparable to twice that of the diploid accessions with large genome size. Polyploid angiosperms can reduce or increase their genome sizes relative to the ancestral diploids (reviewed by Bennetzen, 2002; see also Soltis and Soltis, 1995; Wendel, 2000). Since it is not known the precise diploid ancestor(s) of the tetraploid accessions in A. thaliana, it is impossible to know if the relatively high tetraploid genome size deviates from the sum of the parental values. Generally, cell and organ size in plants is correlated with DNA content (e.g. Strasburger et al., 1991). The significant size differences between seeds from di‐ and tetraploid accessions is therefore expected, while the significance of the negative relationship between mean genome size of the diploids and seed length and width might be an artefact of the high number of samples (n = 700) and the very small Spearman’s rho (less than –0·1). This is also suggested by relatively few accessions with the 10 % larger genome sizes as compared with the large variation of the seed parameters. In addition, the variation of the seed parameters does not correlate with small or large genome sizes.

Genome sizes of the accessions investigated increased slightly but significantly from north to south and from west to east. Previous studies have found positive correlations between the duration of the vegetative period and genome sizes in various angiosperms (Bennett, 1987; Reeves et al., 1998; Turpeinen et al., 1999). This seems to agree with the data given here. However, since A. thaliana can also germinate in autumn as well as in spring, which prolongs the vegetative period, the correlation disagrees with these results. Most accessions are summer annuals; winter annuals are only found in northern Europe (Laibach, 1951). The geographical separation between winter and summer annuals is a quantitative trend rather than a strict replacement, since even in Siberia there are summer annuals among a majority of winter annuals (pers. obs.). Thus, the question remains unanswered as to whether the correlation of genome size and duration of vegetative period found in other angiosperms is characteristic for A. thaliana or is due to sampling artefacts.

Recent molecular studies of the Arabidopsis genome are related to the published ‘Columbia’ sequence and comparisons with parts of the Ler genome (http://www.ncgr.org/cgi‐bin/cereon/cereon_login.pl). Accessions with a significantly larger genome size than the widely used accession ‘Columbia’ have been found. The increased genome size of some accessions may be due to a larger centromeric region (Bennett et al., 2003) but may also involve coding regions. A closer investigation of the sequences involved in the intraspecific genome size differences of A. thaliana could potentially influence the interpretation of comparative studies of naturally occurring variation, including QTL analysis (Alonso‐Blanco and Koornneef, 2000; Mitchell‐Olds, 2001; Schmid et al., 2003).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank C. Koch for her technical assistance. Special thanks go to N. Ermakov and M. H. Hoffmann, who helped collect A. thaliana in Siberia. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to K.B. and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie to A.M.

Received: 11 August 2003;; Returned for revision: 16 October 2003; Accepted: 30 October 2003, Published electronically: 14 January 2004

References

- Alonso‐BlancoC, Koornneef M.2000. Naturally occurring variation in Arabidopsis: an underexploited resource for plant genetics. Trends in Plant Science 5: 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. 2000. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana Nature 408: 796–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ArumuganathanK, Earle ED.1991. Nuclear DNA content of some important plant species. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 9: 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- BarowM, Meister A.2002. Lack of correlation between AT frequency and genome size in higher plants and the effect of non‐randomness of base sequences on dye binding. Cytometry 47: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BarowM, Meister A.2003. Endopolyploidy in seed plants is differently correlated to systematics, organ, life strategy and genome size. Plant, Cell and Environment 26: 571–584. [Google Scholar]

- BeemsterGTS, De Vusser K, De Tavernier E, De Bock K, Inzé D.2002. Variation in growth rate between Arabidopsis ecotypes is correlated with cell division and A‐type cyclin‐dependent kinase activity. Plant Physiology 129: 854–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BennettMD.1987. Variation in genomic form in plants and its ecological implications. New Phytologist 106: 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- BennettMD, Smith JB.1991. Nuclear DNA amounts in angiosperms. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B – Biological Sciences 334: 309–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BennettMD, Leitch IJ, Price HJ, Johnston JS.2003. Comparisons with Caenorhabditis (∼100 Mb) and Drosophila (∼175 Mb) using flow cytometry show genome size in arabidopsis to be ∼157 Mb and thus ∼25 % larger than the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative estimate of ∼125 Mb. Annals of Botany 91: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BennetzenJL.2002. Mechanisms and rates of genome expansion and contraction in flowering plants. Genetica 115: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DolezelJ, Greilhuber J, Lucretti S, Meister A, Lysak MA, Nardi L, Obermayer R.1998. Plant genome size estimation by flow cytometry: inter‐laboratory comparison. Annals of Botany 82 (Suppl. A): 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- FrancisDM, Hulbert SH, Michelmore RW.1990.Genome size and complexity of the obligate fungal pathogen, Bremia lactucae Experimental Mycology 14: 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- GalbraithDW, Harkins KR, Knapp S.1991. Systemic endopolyploidy in Arabidopsis thaliana Plant Physiology 96: 985–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GreilhuberJ.1998. Intraspecific variation in genome size: a critical reassessment. Annals of Botany 82 (Suppl. A): 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- KondorosiE, Roudier F, Gendreau E.2000. Plant cell‐size control: growing by ploidy? Current Opinion in Plant Biology 3: 488–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KrisaiR, Greilhuber J.1997.Cochlearia pyrenaica DC. das Löffelkraut, in Oberösterreich (mit Anmerkungen zur Karyologie und zur Genomgrösse). Beiträge zur Naturkunde Oberösterreichs 5: 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- LaibachF.1951. Über sommer‐ und winteranuelle Rassen von Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Ein Beitrag zur Ätiologie der Blütenbildung. Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen 28: 173–210. [Google Scholar]

- LeutwilerLS, Hough‐Evans BR, Meyerowitz EM.1984. The DNA of Arabidopsis thaliana Molecular and General Genetics 194: 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- MarieD, Brown SC.1993. A cytometric exercise in plant DNA histograms, with 2C‐values for 70 species. Biology of Cell 78: 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MelaragnoJE, Mehrotra B, Coleman AW.1993. Relationship between endoploidy and cell size in epidermal tissue of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 5: 1661–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell‐OldsT.2001.Arabidopsis thaliana and its wild relatives: a model system for ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology 16: 693–700. [Google Scholar]

- ReevesG, Francis D, Davies MS, Rogers HJ, Hodkinson TR.1998. Genome size is negatively correlated with altitude in natural populations of Dactylis polygama Annals of Botany 82 (Suppl. A): 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 23.SPSS. 1999. SPSS for Windows. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc. [Google Scholar]

- SchmidKJ, Rosleff Sörensen T, Stracke R, Törjék O, Altman T, Mitchell‐Olds T, Weisshaar B.2003. Large‐scale identification and analysis of genome‐wide single‐nucleotide‐polymorphisms for mapping in Arabidopsis thaliana Genome Research 13: 1250–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SchmuthsH, Hoffman MH, Bachmann K.2004. Geographic distribution and recombination of genomic fragments on the short arm of chromosome 2 of Arabidopsis thaliana Plant Biology (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SoltisDE, Soltis PS.1995. The dynamic nature of polyploid genomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 92: 8089–8091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StrasburgerE, Noll F, Schenk H, Schimper AFW.1991.Lehrbuch der Botanik für Hochschulen. 33. Auflage. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer. [Google Scholar]

- TurpeinenT, Kulmala J, Nevo E.1999. Genome size variation in Hordeum spontaneum populations. Genome 42: 1049–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VilharB, Greilhuber J, Koce JD, Temsch EM, Dermastia M.2001. Plant genome size measurement with DNA image cytometry. Annals of Botany 87: 719–728. [Google Scholar]

- WendelJF.2000.Genome evolution in polyploids. Plant Molecular Biology 42: 225–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]