Abstract

• Background Elevated levels of atmospheric [CO2] are likely to enhance photosynthesis and plant growth, which, in turn, should result in increased specific and whole-plant respiration rates. However, a large body of literature has shown that specific respiration rates of plant tissues are often reduced when plants are exposed to, or grown at, high [CO2] due to direct effects on enzymes and indirect effects derived from changes in the plant's chemical composition.

• Scope Although measurement artefacts may have affected some of the previously reported effects of CO2 on respiration rates, the direction and magnitude for the effects of elevated [CO2] on plant respiration may largely depend on the vertical scale (from enzymes to ecosystems) at which measurements are taken. In this review, the effects of elevated [CO2] from cells to ecosystems are presented within the context of the enzymatic and physiological controls of plant respiration, the role(s) of non-phosphorylating pathways, and possible effects associated with plant size.

• Conclusions Contrary to what was previously thought, specific respiration rates are generally not reduced when plants are grown at elevated [CO2]. However, whole ecosystem studies show that canopy respiration does not increase proportionally to increases in biomass in response to elevated [CO2], although a larger proportion of respiration takes place in the root system. Fundamental information is still lacking on how respiration and the processes supported by it are physiologically controlled, thereby preventing sound interpretations of what seem to be species-specific responses of respiration to elevated [CO2]. Therefore the role of plant respiration in augmenting the sink capacity of terrestrial ecosystems is still uncertain.

Key words: Respiration, elevated CO2, cellular processes, ecosystem respiration, oxidation

INTRODUCTION

Respiration is essential for growth and maintenance of all plant tissues, and plays an important role in the carbon balance of individual cells, whole-plants and ecosystems, as well as in the global carbon cycle. Through the processes of respiration, solar energy conserved during photosynthesis and stored as chemical energy in organic molecules is released in a regulated manner for the production of ATP, the universal currency of biological energy transformations, and reducing power (e.g. NADH and NADPH). A quantitatively important by-product of respiration is CO2 and, therefore, plant and ecosystem respiration play a major role in the global carbon cycle.

Terrestrial ecosystems exchange about 120 Gt of carbon per year with the atmosphere, through the processes of photosynthesis and respiration (Schlesinger, 1997). Roughly, half of the CO2 assimilated annually through photosynthesis is released back to the atmosphere by plant respiration (Gifford, 1994; Amthor, 1995). Because terrestrial biosphere-atmosphere fluxes of CO2 far outweigh anthropogenic inputs of CO2 to the atmosphere, a small change in terrestrial respiration could have a significant impact on the annual increment in atmospheric [CO2] (Amthor, 1997). A large body of literature has indicated that plant respiration is reduced in plants grown at high [CO2]. For example, it was estimated that the observed 15–20 % reduction in plant tissue respiration caused by doubling current atmospheric [CO2] (Amthor, 1997; Drake et al., 1997; Curtis and Wang, 1998), could increase the net sink capacity of global ecosystems by 3·4 Gt of carbon per year (Drake et al., 1999), and thus offset an equivalent amount of carbon from anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Therefore, not only are gross changes in respiration important for large-scale carbon balance issues, changes in specific rates of respiration can have significant impact on basic plant biology such as growth, biomass partitioning or nutrient uptake (Amthor, 1991; Wullschleger et al., 1994; Drake et al., 1999).

Scaling the effects of an increase in atmospheric [CO2] on plant respiration at the biochemical level to the whole ecosystem is difficult for at least two important reasons: (1) the fine and coarse control points of respiratory pathways in tissues and whole plants are not well known; and (2) it is unclear how respiration rates actively or passively adjust to the effects that elevated [CO2] may have both upstream (e.g. on substrate availability) and downstream (e.g. on energy demand) of the carbon oxidation pathways. In addition, accurate measurements of respiratory rates as CO2 evolution have been proven difficult with current techniques (Gonzalez-Meler and Siedow, 1999; Hamilton et al., 2001; Jahnke, 2001), presenting yet another limitation to scaling up process-based measurements of respiration rates to organism, ecosystem or global levels. In this document, we re-evaluate the theory on respiration responses to elevated [CO2] in view of recent studies that have provided new insights on the effects of a short- and long-term change in atmospheric [CO2] on plant respiration.

DIRECT AND INDIRECT EFFECTS OF [CO2] ON PLANT-SPECIFIC RESPIRATION RATES

Amthor (1991) described two different effects of [CO2] on plant respiration rates that can be distinguished experimentally: a direct effect, in which the rate of respiration of mitochondria or tissues could be rapidly and reversibly reduced following a rapid increase in [CO2] (Amthor et al., 1992; Amthor, 2000a), and an indirect effect in which high [CO2] changes the rate of respiration in plant tissues compared with the rate seen for those plants grown in normal ambient [CO2] when both are tested at a common background [CO2] (Azcón-Bieto et al., 1994). Most of the studies investigating the effects of a change in [CO2] on respiration rates have described magnitude (from non-significant to 60 %) and direction (either stimulation, inhibition or no effect) of these two effects, with little progress on their underlying mechanisms. Confounding measurement artefacts are an added complication for establishing the presence and magnitude of direct and indirect effects of [CO2] on respiration (Gonzalez-Meler and Siedow, 1999; Amthor, 2000a; Jahnke, 2001; Davey et al., 2004).

Direct effects

Previously, a rapid short-term doubling of current atmospheric CO2 levels was reported to inhibit respiration of mitochondria and plant tissues by 15–20 % (Amthor, 1997; Drake et al., 1997; Curtis and Wang, 1998). Although direct effects of [CO2] on respiratory enzymes have been reported, the magnitude of the direct inhibition of intact tissue respiration by elevated [CO2] has now been shown to be explained by measurement artefacts (i.e. Gonzalez-Meler and Siedow, 1999; Jahnke, 2001), diminishing the impact that such reductions in respiration rate may have on plant growth and the global carbon cycle.

Direct effects on enzymes

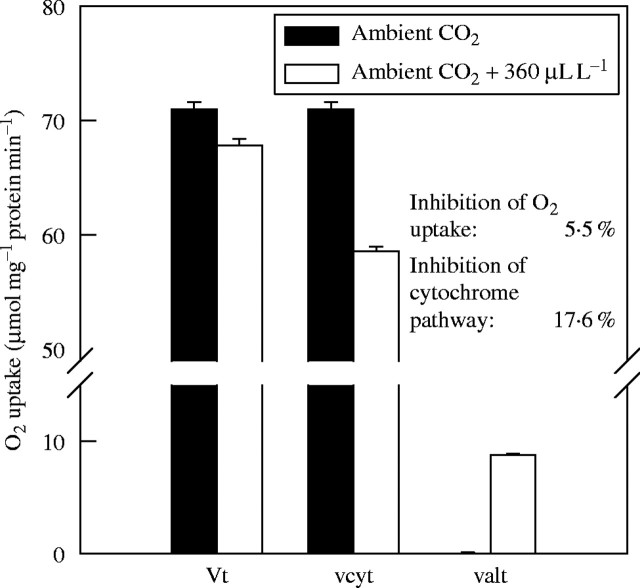

Doubling current levels in [CO2] (here we review the effects of only two- or three-fold increases in atmospheric CO2) have been shown to inhibit the oxygen uptake of isolated mitochondria and the activity of mitochondrial enzymes under some conditions (Reuveni et al., 1995; Gonzàlez-Meler et al., 1996a, b). Twice current atmospheric [CO2] reduces the activity of cytochrome c oxidase and succinate dehydrogenase in isolated mitochondria from cotyledon and roots of Glycine max (Gonzàlez-Meler et al., 1996b). Mitochondrial oxygen uptake may show either no response or up to 15 % inhibition by a rapid increase in [CO2], depending on the electron donor used in the assay (Gonzàlez-Meler et al., 1996b; see also Fig. 1), indicating that the response of mitochondrial enzymes to high [CO2] depends on the cell's metabolism (Gonzalez-Meler and Siedow, 1999; Affourtit et al., 2001).

Fig. 1.

Effect of doubling the concentration of CO2 on the oxygen uptake of mitochondria isolated from 5-d-old soybean cotyledons in state 4 conditions (absence of ADP). Oxidation of NADH and pyruvate was measured in intact mitochondria that were incubated for 10 min with 0 (open bars) or 0·1 (solid bars) mm dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) at 25 °C. Experiments were done using the oxygen isotope technique as described in Ribas-Carbo et al. (1995) to detect the effects of CO2 on the total activity of mitochondrial respiration (Vt), the activity of the cytochrome pathway (vcyt) and the activity of the alternative pathway (valt). Results are average of four replicates and standard errors.

In scaling the direct effects of high [CO2] on respiratory enzymes to intact tissues two factors need to be considered: (1) cytochrome oxidase exerts up to 50 % of the total respiratory control (for definitions, see Kacser and Burns, 1979) at the level of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (reviewed by Gonzalez-Meler and Siedow, 1999); and (2) the competitive nature of the cytochrome and alternative pathways of mitochondrial respiration (Affourtit et al., 2001). The activity of the alternative pathway of respiration could increase upon doubling of the [CO2], masking a direct CO2 inhibition of the cytochrome pathway (Fig. 1). The oxygen isotope technique (Ribas-Carbo et al., 1995) allows for the distinction of direct effects of [CO2] on oxygen uptake activity by the cytochrome and the alternative oxidases. Figure 1 shows that mitochondrial electron transport activity is affected when CO2 (a mild inhibitor) restricts the normal electron flow through one of the pathways (Cyt pathway – vcyt). Under conditions of low alternative pathway activity (for details, see Ribas-Carbo et al., 1995), inhibition of the cytochrome pathway (18 %) by doubling the ambient [CO2] is compensated for by a similar increase in alternative pathway activity (valt), resulting in no significant reduction in overall oxygen uptake of the isolated mitochondria. These results show that enhanced activity of the alternative pathway upon an increase in [CO2] provides a mechanism by which the direct [CO2] inhibition of the cytochrome oxidase may not be seen in the total oxygen uptake under conditions of high adenylate control (low ADP). Gonzàlez-Meler and Siedow (1999) argued that direct effects of CO2 on respiration exceeding >10 % inhibition are likely due to factors other than inhibition of mitochondrial enzymes. Due to confounding measurement artefacts (Jahnke, 2001), rates of tissue respiration have been reported to decrease >10 % when the atmospheric [CO2] doubles.

Direct effects on intact tissues

Recent evidence indicates that, in studying direct effects of CO2 on respiratory CO2 efflux of intact tissues, investigators should first be concerned about measurement artefacts. Amthor (1997) and Gonzalez-Meler and Siedow (1999) showed that gas CO2 exchange measurement errors could augment and explain the magnitude of the direct effect. New studies made in this context have shown that respiration rates are little or not at all inhibited by a doubling of atmospheric [CO2] (Amthor, 2000a; Amthor et al., 2001; Bunce, 2001; Hamilton et al., 2001; Tjoelker et al., 2001; Bruhn et al., 2002; Davey et al., 2004). Indeed, Jahnke (2001) and Jahnke and Krewitt (2002) confirmed that measurement artefacts due to leakage in CO2-exchange systems could be as large as the previously reported direct inhibitory effects. They also found that leaks through the aerial spaces of homobaric leaves showed a significant apparent inhibition of CO2 efflux that was not due to an inhibition of respiration by elevated [CO2]. Therefore, considerations of the impact direct effects of [CO2] on plant respiration rates may have on the global carbon cycle were overstated (Gonzalez-Meler et al., 1996a; Drake et al., 1999). Corrections for instrument leaks can be applied in most cases (Bunce, 2001; Jahnke, 2001; Pons and Welschen, 2002). Applying some corrections for gas exchange leaks, Bunce (2001) reported a significant reduction in respiration after a rapid increase in [CO2]. Moreover, simultaneously switching the air isotopic composition from 12CO2 to pure 13CO2 when the [CO2] was changed, showed that the efflux of 12CO2 (which represents net respiratory CO2 evolution originating from respiratory substrates minus the CO2 being re-fixed by carboxylases, see below) was reduced in leaves of C3 plants, but not C4, when the [CO2] increased (Pinelli and Loreto, 2003). These recent results illustrate that not all reports of direct inhibition of respiration by elevated [CO2] have yet been reconciled with each other, but they do not show a clear proof that the direct effect, as defined by Amthor (1991) exits either.

An alternate explanation for the apparent reduction in respiration rates upon an increase in [CO2] (Bunce, 2001; Pinelli and Loreto, 2003) is an increase in dark CO2 fixation catalysed by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC), resulting in an apparent reduction of CO2 efflux (Amthor, 1997; Drake et al., 1999). However, in Rumex and Glycine leaves, Amthor et al. (2001) found an effect of elevated [CO2] on CO2 efflux in only a minority of experiments, with no effect of elevated [CO2] on the O2 uptake of the same leaves, indicating at most a small effect of elevated [CO2] on PEPC activity or respiration rates. Similar results were found for a variety of species, involving 600 measurements, in which [CO2] increases did not alter the CO2 and O2 leaf exchanges in the dark (Davey et al., 2004).

It seems that direct effects of [CO2] on mitochondrial enzymes may have no consequence on the specific respiratory rate of whole tissues. Because mitochondrial respiratory enzymes are generally ‘in excess’ to the levels required to support normal tissue respiratory activity under most growth conditions (Gonzalez-Meler and Siedow, 1999; Atkin and Tjoelker, 2003; Gonzalez-Meler and Taneva, 2004), a minor inhibition of enzymatic activity by [CO2] will not translate to the overall tissue respiration rate. A small increase in enzyme levels in plants exposed to elevated [CO2] could be enough to compensate for the direct effects of CO2 on mitochondrial enzyme activity, as it has been seen in leaves of some plants grown at high [CO2] (i.e. Griffin et al., 2001).

Another factor to consider is that increases in alternative pathway activity upon inhibition of cytochrome oxidase by a change in [CO2] will result in unaltered dark respiratory rates (as illustrated in Fig. 1). However, an increase in the non-phosphorylating activity of the alternative pathway reduces the efficiency with which energy from oxidized substrates supports growth and maintenance of plants (Gonzalez-Meler and Siedow, 1999; Gonzalez-Meler and Taneva, 2004). Some studies have reported that the growth of plants exposed to elevated [CO2] only during the night-time is altered (Bunce, 1995, 2001, 2002; Reuveni et al., 1997; Griffin et al., 1999). Such altered growth patterns have been attributed, in part, to effects of [CO2] on plant respiration, including increased activity of the non-phosphorylating alternative pathway. These CO2 effects are considered next.

Are there direct effects of CO2 on whole plants?

In the past, in some studies, plants have been grown at [CO2] elevated only at night-time to assess the long-term consequences of the previously considered direct effects of CO2 on respiration rates. Although most of these studies have found that growth patterns were altered in plants exposed to high night-time [CO2], these effects cannot be attributed to direct effects of [CO2] on respiration for reasons explained above. Bunce (1995) observed that the biomass and leaf area ratio of Glycine max increased and that photosynthetic rates decreased in plants exposed to high night-time [CO2] relative to plants grown at normal ambient [CO2]. Similarly, Griffin et al. (1999) found that Glycine max exposed to high night-time [CO2] had lower leaf respiration rates and greater biomass than plants grown at ambient or elevated [CO2]. Reuveni et al. (1997) speculated that increases in the biomass of Lemna gibba grown at high night-time [CO2] relative to control plants, was due to a reduction in alternative pathway respiration (although the alternative pathway activity was not measured). Reduction in alternative pathway activity might more fully couple respiration rates with growth and maintenance, enhancing growth. In contrast, Ziska and Bunce (1999) showed that elevation of night-time [CO2] reduced biomass only in two of the four C4 species studied. In a later study, Bunce (2002) described that carbohydrate translocation was reduced within 2 d of exposing plants to elevated night-time [CO2] when compared with plants grown at ambient conditions day and night. These results suggest that elevated [CO2] may have other uncharacterized direct effects on plant physiology that can have the consequence of reducing energy demand for carbohydrate translocation, hence reducing the rate of leaf respiration. If so, these new types of effects cannot be catalogued as direct effects of [CO2] on respiration but as indirect effects, making more research in this area necessary.

In summary, even though rapid changes in [CO2] can inhibit the activity of some mitochondrial enzymes directly, previously reported direct effects of [CO2] on tissue respiration are likely to be due to measurement artefacts. Therefore, direct effects of [CO2] on specific respiration rates (although not necessarily on respiration physiology) should be dismissed as having a major impact on the amount of anthropogenic carbon that vegetation could retain. The role of the alternative pathway in direct respiratory responses to elevated [CO2], although unresolved, would have little impact, if any, on the general conclusion that direct effects of [CO2] on plant respiration are not to be considered in plant growth or carbon cycle models. Other effects of long-term elevation of night-time [CO2] can alter plant growth characteristics, and indirectly affect both respiration rates and the relative activity of the cytochrome and alternative pathways. Therefore these effects cannot be referred to as direct effects but rather as indirect effects of [CO2] on respiration rates.

Indirect effects

Indirect CO2 effects represent changes in tissue respiration in response to plant growth at elevated atmospheric [CO2] (Amthor, 1997), because of changes in tissue composition (Drake et al., 1997). Other indirect effects of [CO2] on plant respiration include changes in growth or response to environmental stress, as well as changes in the respiratory demand for energy relative to that of plants grown at ambient [CO2] (Bunce, 1994; Amthor, 2000b). Such indirect effects of plant growth at elevated [CO2] can be detected as a reduction in CO2 emission (or O2 consumption) from plant tissues when measured at ambient [CO2] (Gonzalez-Meler et al., 1996a).

Indirect effects on enzymes: is there acclimation of respiration to elevated [CO2]?

Acclimation of respiration to high [CO2] can be defined as the down- or up-regulation of the respiratory machinery (i.e. amount of respiratory enzymes, number of mitochondria) irrespective of changes in specific respiration rates when plants are grown at elevated [CO2] (Drake et al., 1999). A change in the leaf respiratory machinery of plants grown at high [CO2] can be expected because of (a) increases in carbohydrate content, (b) reduced photorespiratory activity and (c) reductions in leaf protein content (15 % on average), when compared with plants grown at current ambient [CO2] (Drake et al., 1997). These three processes can have different and sometimes opposite effects on levels of respiratory enzymes and specific rates of respiration.

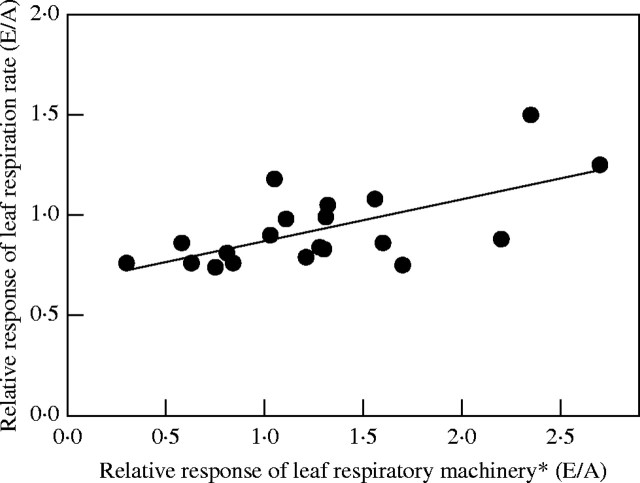

As atmospheric [CO2] rises, increased photosynthesis results in higher cellular carbohydrate concentrations (Drake et al., 1997; Curtis and Wang, 1998). Increased carbohydrates can stimulate the specific activity of respiration, due to the greater availability of respiratory substrates (Azcón-Bieto and Osmond, 1983) and higher energy demand for phloem loading of carbohydrates (Bouma et al., 1995; Körner et al., 1995; Amthor, 2000b). Additionally, increased tissue carbohydrate levels (as in the case of plants grown at high [CO2]) could result in an increase of transcript levels of cytochrome oxidase (Felitti and Gonzalez, 1998; Curi et al., 2003) and cytochrome pathway activity (Gonzalez-Meler et al., 2001). In contrast, a reduction in photorespiratory activity in plants grown at high [CO2] will reduce the need for the mitochondrial compartment, which may result in a reduction in mitochondrial proteins and functions (Amthor, 1997; Drake et al., l999; Bloom et al., 2002). Not surprisingly, the available studies show that levels and activity of respiratory machinery can either increase or decrease in leaves of plants grown at high [CO2] with no concomitant effects on respiration rates (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between the relative response of leaf respiration and the leaf respiratory machinery of plants grown at ambient and elevated [CO2]. Data extracted from Azcon-Bieto et al. (1994), George et al. (1996), Gonzalez-Meler et al. (1996a), Griffin et al. (2001, 2004), Hrubec et al. (1985), Tissue et al. (2002), Wang et al. (2004) and M. A. Gonzalez-Meler (unpubl. res.). *Respiratory machinery refers to changes in either number of mitochondria, or soluble or membrane enzyme activity in plant extracts from plants grown at either ambient or elevated [CO2] in field and laboratory experiments. Only studies that have provided both respiration rates and respiratory machinery from the same tissues or from different tissues from the same plants are considered. Rates of [CO2] evolution used are only those measured for plants grown under ambient or elevated [CO2] at ambient [CO2] conditions.

For instance, indirect effects of elevated [CO2] on respiration of leaves of Lindera benzoin and stems of Scirpus olneyi were correlated with a reduction in maximum activity of cytochrome oxidase (Azcon-Bieto et al., 1994). However, a reduction of respiratory enzyme activity was not seen in rapidly growing tissues exposed to elevated [CO2] (Perez-Trejo, 1981; Hrubeck et al., 1985). No acclimation to elevated [CO2] (i.e. reduction in cytochrome oxidase) has been observed in leaves of C4 plants (Azcon-Bieto et al., 1994) or roots of C3 plants (Gonzalez-Meler et al., 1996a). In contrast, the number of mitochondria is consistently shown to increase in response to plant growth at elevated [CO2] (Griffin et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2004). Overall changes associated with increases or decreases in the respiratory machinery in leaves of plants grown at elevated [CO2] (i.e. mitochondrial counts, cytochrome oxidase maximum activity) seem to be independent of responses of the respiration rates to elevated [CO2] (Fig. 2; r2 = 0·, n.s.). Therefore, changes in the mitochondrial machinery of plants grown in high [CO2] are associated with altered mitochondrial function and biogenesis and are not necessarily related to energy production. Anaplerotic functions of mitochondrial activity provide reductant and carbon skeletons for the production of primary and secondary metabolites used in growth and maintenance processes, as well as other processes such as nitrogen reduction and assimilation (Gonzalez-Meler et al., 1996a; Amthor, 1997; Bloom et al., 2002; Davey et al., 2004). Vanoosten et al., (1992) reported increases in fumarase and malic enzyme activities in leaves of Picea abies grown in high [CO2]. These increases contrasted with unchanged or decreased activity of PEPC or glycolitic enzymes. Increase in enzyme activity of the tricarboxylic acid cycle with no increase in respiration rates may support the export of carbon skeletons and reducing power (mainly as malate) from the mitochondria to the cytosol for biosynthesis. This uncoupling between an increase in mitochondrial numbers and no increase in respiratory activity of plants grown at high [CO2] (Fig. 2) is further illustrated by the study of Tissue et al. (2002) in which a more than two-fold increase in the leaf mitochondrial counts did not alter the maximum activity of cytochrome oxidase in the same tissues. With the exception of two studies (i.e. Azcon-Bieto et al., 1994; Tissue et al., 2002), there are no reports on the response of membrane-associated mitochondrial enzymes to elevated [CO2] in leaves or roots of plants. More research is needed in this area.

Indirect effects of [CO2] on respiration of tissues and whole plants

It has been historically accepted that leaf respiration is reduced as a consequence of plant growth at elevated [CO2] (El Kohen et al., 1991; Isdo and Kimball, 1992; Wullschleger et al., 1992a; Amthor, 1997; Drake et al., 1997; Curtis and Wang, 1998; Norby et al., 1999). Poorter et al. (1992) showed that leaf respiration was reduced, on average, by 14 % when expressed on a leaf mass basis, but increased by 16 % on a leaf area basis. Curtis and Wang (1998) compiled respiratory data for woody plants, and observed that growth at elevated [CO2] resulted in an 18 % inhibition of leaf respiration (mass basis). In this section we will concentrate on the effects of elevated [CO2] on respiration of above-ground tissues. It is worth noting, however, that root respiration rates in the field are not altered by growth at elevated [CO2] during most of the plant's growing season (Johnson et al., 1994; Matamala and Schlesinger, 2000). Total ecosystem root respiration may increase if root mass and/or turnover increases (Hungate et al., 1997; Hamilton et al., 2002; George et al., 2003; Matamala et al., 2003).

Many previous reviews and meta-analyses (see above) have compared respiratory rates of plants grown and measured at the [CO2] at which plants were grown. Therefore, these respiration measurements are also susceptible by the gas exchange artefacts described by Jahnke and co-workers. Respiratory O2 uptake measured in closed systems is not susceptible to the measurement artefacts described above. The O2 uptake of green tissues of plants grown at high [CO2] could be increased, reduced or unaltered when compared with plants grown at ambient [CO2] (Table 1). Davey et al. (2004) also showed that the O2 uptake of leaves of plants grown at high [CO2] was slightly increased relative to control plants. Gas exchange leaks (Jahnke, 2001) should not be a factor in determining the rates of CO2 emission rates when rates are measured and compared at ambient [CO2] for plants grown at ambient and elevated [CO2]. A re-analysis of the literature focused on leaf respiratory responses (on a leaf mass basis) of plants grown at ambient and elevated [CO2] and measured at an ambient [CO2], suggests that specific leaf respiration rates will be unaltered or even increased in plants grown at elevated [CO2] (Table 2). Therefore, the generally accepted onclusion that respiration rates of plants grown at elevated [CO2] is reduced relative to plants grown at ambient [CO2] should be re-evaluated (Amthor, 2000a; Davey et al., 2004; Gonzalez-Meler and Taneva, 2004). However, there is significant variability in the leaf respiratory response to growth at elevated [CO2] when compared with plants grown at ambient conditions, ranging from 40 % inhibition (Azcon-Bieto et al., 1994) to 50 % stimulation (Williams et al., 1992). Considerations on the physiological basis by which the acclimation response of respiration to elevated [CO2] varies, is considered next.

Table 1.

Indirect effects of [CO2] on the dark O2 uptake rates (on a leaf area basis) at 25 °C of green tissues from Scirpus olneyi (C3), Spartina patens (C4), Distchilis spicata (C4), Lindera benzoin (C3), Cinna arundinacea (C3), Quercus geminata (C3), Quercus myrtifolia (C3) and Serenoa repens (C3) plants grown at either normal ambient (A) or normal ambient + 340 mL L−1 atmospheric CO2 (E), inside open-top chambers in the field

| Species |

Dark O2 uptakea |

Dry weight per unit areaa |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saltmarsh | ||||

| Scirpus olneyi | 0·79** | 1·00 | ||

| Spartina patens | 0·94 | 0·99 | ||

| Distchilis spicata | 1·22* | 1·00 | ||

| Woodland understorey | ||||

| Lindera benzoin | 0·77** | 0·96 | ||

| Cinna arundinacea | 1·13 | 1·05 | ||

| Scrub oak–saw palmetto | ||||

| Quercus geminata | 1·31* | 1·11* | ||

| Quercus myrtifolia | 0·82** | 1·24** | ||

| Serenoa repens | 0·96 | 1·02 | ||

E/A.Samples were collected at sunrise during the early summer of 1993.

Oxygen uptake was measured at ambient conditions in a liquid phase oxygen electrode as described in Azcon-Bieto et al. (1994).

Significant differences (Student's t-test) between respiratory rates of plants grown at ambient and elevated [CO2] at P < 0·1 (*) and P < 0·05 (**) are indicated.

Table 2.

Indirect effects of the elevation in atmospheric [CO2] on the dark CO2 efflux of leaves on a dry mass basis based on literature surveys

| Reference |

E/A |

No. of species |

Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amthor (1997) | 0·96 | 21 | 26 studies, crop and herbaceous and woody wild species |

| Davey et al. (2004) | 1·07 | 7 | 1 study, crop and herbaceous and woody wild species |

| Drake et al. (1997) | 0·95 | 17 | 15 studies, crop and herbaceous wild species |

Elevated-over-ambient (E/A) refers to the ratio of rate of leaf dark respiration of plants grown in elevated CO2 to the rate of plants grown in current ambient CO2, when measured at a common CO2 concentration. Under these conditions, effects of gas exchange leaks should not be affecting the comparison of rates of respiration from plants grown at ambient and elevated CO2.

In boreal species, reduction of respiration of plants grown at high [CO2] was related to changes in tissue N and carbohydrate concentration (Tjoelker et al., 1999). Tissue N concentration often decreases in plants grown at elevated [CO2] (Drake et al., 1997; Curtis and Wang, 1998). It is expected that respiration rate would be lower in tissues having lower [N], because the respiratory cost associated with protein turnover and maintenance is a large portion of dark respiration (Bouma et al., 1994). Hence, the metabolic cost (i.e. respiratory energy demand) for construction and maintenance of tissues with high protein concentration is greater than the cost for the maintenance of the same tissue with low [N] (assuming there are no changes in rates of protein turnover between plants grown at ambient and elevated [CO2]) (Amthor, 1989; Drake et al., 1999). This idea was confirmed for leaves of Quercus alba seedlings grown in open-top chambers in the field, where respiration was 21–56 % lower under elevated [CO2] than under ambient [CO2] (Wullschleger and Norby, 1992). The growth respiration component of these leaves was reduced by 31 % and the maintenance component by 45 %. These effects were attributed to the reduced cost of maintaining tissues having lower [N]. Similar results were obtained in leaves and stems of plants of other species (Wullschleger et al., 1992a, b, 1997; Amthor et al., 1994; Carey et al., 1996; Griffin et al., 1996b; Dvorak and Oplustilova, 1997; Will and Ceulemans, 1997), with some exceptions (e.g. Wullschleger et al., 1995).

The growth component of respiration (Amthor, 2000b) could also be reduced in plants grown at elevated [CO2] as a result of altered tissue chemistry (Griffin et al., 1993). Based on the chemical composition of tissues, Poorter et al. (1997) found that elevated [CO2] could reduce growth construction costs by 10–20 %. Griffin et al. (1993, 1996a) also observed reductions in construction costs of Pinus taeda seedlings grown at elevated [CO2]. Hamilton et al. (2001) reported that elevated [CO2] slightly reduced construction costs of leaves of mature trees (including P. taeda) at the top of the canopy, but not at the bottom of the canopy. Such a small reduction can be explained by reductions in tissue [N], as observed in leaves exposed to high [CO2] at the top of the canopy. Changes in construction costs did not result in a decrease in the leaf respiration rates of P. taeda trees exposed to elevated [CO2] (Hamilton et al., 2001).

The lack of long-term effects of increased [CO2] on specific plant respiration rates could also be due to a lower involvement of the alternative pathway (Gonzalez-Meler and Siedow, 1999; Griffin et al., 1999). Respiration through the alternative pathway bypasses two of the three sites of proton translocation; so the free energy released is lost as heat, and is unavailable for the synthesis of ATP. Respiration associated with this pathway will not support growth and maintenance processes of tissues as efficiently as respiration through the cytochrome path. On the other hand, the activity of the alternative pathway of respiration could decrease upon doubling [CO2], masking increases in the activity of the cytochrome pathway and making respiration more efficient, as it was the case in understorey trees grown under elevated [CO2] (Gonzalez-Meler and Taneva, 2004).

Despite earlier reports, the responses of plant respiration to growth under high [CO2] are variable and perhaps species specific, although the overall trend may be a moderate increase in respiration rates of leaves of plants grown under elevated [CO2] relative to the ambient ones (Tables 1 and 2). Ultimately, altered specific respiration rates of tissues will depend on the net balance between the demand for ATP from maintenance (including phloem loading and unloading) and growth processes and on carbon allocation patterns between sinks and source tissues. The fact that the mitochondrial machinery has been shown to increase in leaves of plants grown at elevated [CO2] suggests, however, a larger participation of mitochondria in functions other than oxidative phosphorylation. Finally, indirect effects of [CO2] on tissue respiration rates can be augmented or offset by changes in plant size and/or changes in carbon allocation between plant parts.

INTEGRATED EFFECTS OF ELEVATED [CO2] ON PLANT RESPIRATION AT THE ECOSYSTEM LEVEL

Terrestrial ecosystems exchange about 120 Gt of carbon per year with the atmosphere, through the processes of photosynthesis (leading to gross primary production, GPP) and ecosystem respiration (Re) (Schlesinger, 1997). The difference between GPP and Re determines net ecosystem productivity (NEP), the net amount of carbon retained or released by a given ecosystem. Currently, the net exchange of C between the terrestrial biosphere and the atmosphere is estimated to result in a global terrestrial sink of about 2 Gt of carbon per year (Gifford, 1994; Schimel, 1995; Steffen et al., 1998). Unfortunately, the effects of [CO2] on plant and heterotrophic respiration at the ecosystem level are not well understood, despite their potential to control ecosystem carbon budgets (Ryan, 1991; Giardina and Ryan, 2000; Valentini et al., 2000).

Annually, terrestrial plant respiration releases 40–60 % of the total carbon fixed during photosynthesis (Gifford, 1994; Amthor, 1995) representing about half of the annual input of CO2 to the atmosphere from terrestrial ecosystems (Schlesinger, 1997). Therefore the magnitude of terrestrial plant respiration and its responses to [CO2] are important factors governing the intrinsic capacity of ecosystems to store carbon. Plant respiration responses to high [CO2] may stem from several mechanisms (in absence of direct effects on respiration rates): (a) indirect effects; (b) changes in total plant biomass; and (c) changes in plant carbon allocation. If it is confirmed that the response of overall terrestrial plant respiration to an increase in atmospheric [CO2] is small (Tables 1 and 2), then changes in global plant respiration should be proportional to changes in biomass. However, experimental evidence suggests otherwise, or that the response of plant respiration at the ecosystem level to elevated [CO2] may be more a function of carbon allocation patterns rather than just of increases in plant size (Drake et al., 1996; Hamilton et al., 2002).

Attempts to scale [CO2] effects on mitochondrial or tissue respiration to the ecosystem level are problematic because, unlike photosynthesis, little is known about applicable scaling methods for plant respiration (Gifford, 2003). Current attempts to build respiratory carbon budgets at the canopy level require knowledge of maintenance and growth respiration (see above), as well as tissue respiratory responses to light, temperature and [CO2] (Amthor, 2000b; Gifford, 2003; Turnbull et al., 2003) or have been based on theoretical respiration-to-photosynthesis ratios (i.e. Norby et al., 2002). The respiration-to-photosynthesis ratio was not affected by elevated [CO2] in soybean plants (Ziska and Bunce, 1998) but was reduced in pine forests stands (Hamilton et al., 2002) when compared with ambient controls. The limited available data on the effects of elevating the [CO2] on intact field ecosystems on plant and total ecosystem respiration are summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Contribution of CO2-induced reduction in ecosystem respiration (Re) to total net ecosystem productivity in a C3-dominated salt-marsh ecosystem exposed to elevated [CO2] since 1988

% CO2 stimulation.

Relative change in CO2 stimulation was calculated form the annual canopy flux at elevated plots over that of the ambient ones (n = 5) on a ground area basis.

Modified from Drake et al. (1996) and M. A. Gonzalez-Meler (unpubl. res.).

Table 4.

The effect of elevated [CO2] on ecosystem-level plant gas exchange of forested ecosystems

| [CO2] increase (μL L−1) |

GPPa |

Raa |

NPPa |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | 1·18 | 0·94 | 1·27 | Hamilton et al. (2002) |

| 200 | 1·15 | 1·09 | 1·24 | Schaefer et al. (2003) |

| 150 | 1·21 | 1·21 | 1·21 | Norby et al. (2002) |

| 400 | 1·36 | 1·41 | 1·24 | R. J. Trueman (unpubl. res.) |

E/A.

The ratios of elevated (E) over ambient (A) rates of gross primary productivity (GPP), stand-level plant respiration (Ra) and net primary productivity (NPP) were extracted from Hamilton et al. (2002), Norby et al. (2002), Schaefer et al. (2003) and R. J. Trueman and M. A. Gonzalez-Meler (unpubl. res.).

The contribution of CO2-induced changes in ecosystem respiration to annual NEP of an intact salt marsh exposed to elevated [CO2] in open-top chambers is shown in Table 3. In this ecosystem, elevation of atmospheric CO2 by 350 μL L−1 over ambient levels consistently reduced night-time ecosystem respiration in C3 and C4 community stands (Drake et al., 1996). Net ecosystem productivity increased in stands exposed to elevated [CO2] because the decrease in respiration was accompanied by increases in GPP. The reduction in annual respiration in this ecosystem represented from one-fifth to one-third of the difference in NEP between ambient and elevated open-top chambers (Table 3). Ecosystem-level plant respiration in forest stands, however, may not be reduced by elevated [CO2] as in the case of the salt marsh (Table 4).

In forests exposed to elevated [CO2] using free air CO2 enrichment (FACE), GPP was stimulated by 15–36 % (Table 4) over ambient stands, resulting in consistent increases in net primary productivity (NPP). Increases in GPP and NPP seemed to be accompanied by variable responses on whole-plant respiration, which could be increased by as much as 20 % (Table 4). For instance, Hamilton et al. (2002) found that elevated [CO2] increased forest NPP by 27 % without any increase in total plant ecosystem respiration. This result can be explained by a possible decrease in specific respiration rates at high [CO2] accompanied by larger biomass of plants grown at elevated [CO2]. In a Popolus deltoides plantation at Biosphere 2 centre, elevated [CO2] increased stand-level plant respiration by 40 % when compared with ambient (Table 4). The total increase in stand-level plant respiration was larger than the CO2 stimulation of NPP, suggesting that, in this case, specific respiration rates and plant size both contributed to the increase in plant respiration of trees grown in high [CO2] (R. J. Trueman and M. A. Gonzalez-Meler, unpubl. res.).

Some studies suggest that increases in ecosystem-level plant respiration in ecosystems exposed to elevated [CO2] mainly occur in below-ground plant tissues (Hungate et al., 1997; Lin et al., 2001; Hamilton et al., 2002), which in turn may stimulate soil respiration rates (Zak et al., 2000; Pendall et al., 2003). This requires a substantial proportion of the additional C assimilated by plants growing at elevated [CO2] to be allocated to roots for growth and turnover (Johnson et al., 1994; Hungate et al., 1997; King et al., 2001; Matamala et al., 2003). Greater plant C allocation below ground can theoretically increase the contribution of root respiration to total soil respiration because of greater root biomass relative to ambient [CO2]. However, Hamilton et al. (2002) reported increases in total root respiration in a forest exposed to elevated [CO2], where root mass, turnover (Matamala et al., 2003) or respiration rates (Matamala and Schlesinger, 2000; George et al., 2003) were not affected by the CO2 treatment. The apparent disparity may be due to the different methodologies employed in these studies and in the contribution of rhizosphere activity to soil CO2 efflux, emphasizing the need for more coordinated research in building ecosystem carbon budgets using multiple approaches, especially below ground.

In conclusion and contrary to what was previously thought, specific respiration rates are generally not reduced when plants are grown at elevated [CO2]. This is because direct effects of [CO2] on respiratory enzymes are inconsequential to specific respiration rates of tissues. A re-analysis of the literature comparing respiration of leaves of plants grown at ambient [CO2] with leaves of plants grown at elevated [CO2] when rates are measured at the same [CO2], indicate that leaf respiration on average will not be greatly changed by increasing atmospheric [CO2]. Increases in growth rates appear to be compensated for by changes in tissue chemistry that affect growth and maintenance respiration. If specific rates of respiration are not affected by growth at elevated [CO2], respiration from the terrestrial vegetation in a high-CO2 world should be proportional to changes in plant biomass. However, whole ecosystem studies show that canopy respiration does not increase proportionally to increases in biomass when natural ecosystems are exposed to elevated atmospheric [CO2]. Field studies also suggest that a larger proportion of plant respiration takes place in the root system under elevated [CO2] conditions. Fundamental information is still lacking on how respiration and the processes supported by it are physiologically controlled, thereby preventing sound interpretations of what seem to be species-specific responses of respiration to elevated [CO2]. Therefore the role of plant respiration in augmenting the sink capacity of terrestrial ecosystems is still uncertain.

Acknowledgments

This review is part of a lecture given at the International Congress of Plant Mitochondria held in Perth in July 2002, partly sponsored by Annals of Botany. M.A.G.-M. specially thanks Jeff Amthor for his work in this area, his thoughts, discussions and specific comments in parts of this manuscript. Authors also wish to thank Joaquim Azcon-Bieto, Bert Drake, Evan DeLucia, Steve Long, Miquel Ribas-Carbo and Jim Siedow for their discussion on the effects of elevated [CO2] on respiration of organelles, plants and ecosystems over the years. We acknowledge financial support by US Department of Agriculture (M.A.G.-M.), UIC fellowship (L.T.), and Sigma Xi and provost awards to L.T. and R.J.T.

LITERATURE CITED

- Affourtit C, Krab K, Moore AL. 2001. Control of plant mitochondrial respiration. Biochimica Biophysica Acta – Bioenergetics 1504: 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor JS. 1989.Respiration and crop productivity. New York: Springer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Amthor JS. 1991. Respiration in a future, higher CO2 world. Plant, Cell and Environment 14: 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Amthor JS. 1995. Terrestrial higher-plant response to increasing atmospheric [CO2] in relation to the global carbon cycle. Global Change Biology 1: 243–274. [Google Scholar]

- Amthor JS. 1997. Plant respiratory responses to elevated CO2 partial pressure. In: Allen LH, Kirkham MB, Olszyk DM, Whitman CE, eds. Advances in carbon dioxide effects research. American Society of Agronomy Special Publication (proceedings of 1993 ASA Symposium, Cincinnati, OH), Madison, WI: ASA, CSSA and SSSA, 35–77. [Google Scholar]

- Amthor JS. 2000. Direct effect of elevated CO2 on nocturnal in situ leaf respiration in nine temperate deciduous trees species is small. Tree Physiology 20: 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor JS. 2000. The McCree–de Wit–Penning de Vries–Thornley respiration paradigms: 30 years later. Annals of Botany 86: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Amthor JS, Koch G, Boom AJ. 1992. CO2 inhibits respiration in leaves of Rumex crispus L. Plant Physiology 98: 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor JS, Koch GW, Willms JR, Layzell DB. 2001. Leaf O2 uptake in the dark is independent of coincident CO2 partial pressure. Journal Experimental Botany 52: 2235–2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor JS, Mitchell RJ, Runion GB, Rogers HH, Prior SA, Wood CW 1994. Energy content, construction cost and phytomass accumulation of Glycine max (L.) Merr. and Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench grown in elevated CO2 in the field. New Phytologist 128: 443–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin OK, Tjoelker MG. 2003. Thermal acclimation and the dynamic response of plant respiration to temperature. Trends in Plant Science 8: 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcón-Bieto J, Osmond CB. 1983. Relationship between photosynthesis and respiration. The effect of carbohydrate status on the rate of CO2 production by respiration in darkened and illuminated wheat leaves. Plant Physiology 71: 574–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcón-Bieto J, Gonzàlez-Meler MA, Doherty W, Drake BG. 1994. Acclimation of respiratory O2 uptake in green tissues of field grown native species after long-term exposure to elevated atmospheric CO2 Plant Physiology 106: 1163–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom AJ, Smart DR, Nguyen DT, Searles PS. 2002. Nitrogen assimilation and growth of wheat under elevated carbon dioxide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 99: 1730–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouma TJ, De Viser R, Janseen JHJA, De Kick MJ, Van Leeuwen PH, Lambers H. 1994. Respiratory energy requirements and rate of protein turnover in vivo determined by the use of an inhibitor of protein synthesis and a probe to assess its effect. Physiologia Plantarum 92: 585–594. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma TJ, De Viser R, Van Leeuwen PH, De Kick MJ, Lambers H. 1995. The respiratory energy requirements involved in nocturnal carbohydrate export from starch-storing mature source leaves and their contribution to leaf dark respiration. Journal of Experimental Botany 46: 1185–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn D, Mikkelsen TN, Atkin OK. 2002. Does the direct effect of atmospheric CO2 concentration on leaf respiration vary with temperature? Responses in two species of Plantago that differ in relative growth rate. Physiologia Plantarum 114: 57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunce JA. 1994. Responses of respiration to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. Physiologia Plantarum 90: 427–430. [Google Scholar]

- Bunce JA. 1995. Effects of elevated carbon dioxide concentration in the dark on the growth of soybean seedlings. Annals of Botany 75: 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- Bunce JA. 2001. Effects of prolonged darkness on the sensitivity of leaf respiration to carbon dioxide concentration in C3 and C4 species. Annals of Botany 87: 463–468. [Google Scholar]

- Bunce JA. 2002. Carbon dioxide concentration at night affects translocation from soybean leaves. Annals of Botany 90: 399–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey EV, DeLucia EH, Ball JT. 1996. Stem maintenance and construction respiration in Pinus ponderosa grown in different concentrations of atmospheric CO2 Tree Physiology 16: 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curi GC, Welchen E, Chan RL, Gonzalez DH. 2003. Nuclear and mitochondrial genes encoding cytochrome c oxidase subunits respond differently to the same metabolic factors. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 41: 689–693. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis PS, Wang X. 1998. A meta-analysis of elevated CO2 effects on woody plant mass, form, and physiology. Oecologia 113: 299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey PA, Hunt S, Hymus GJ, DeLucia EH, Drake BG, Karnosky DF, Long SP. 2004. Respiratory oxygen uptake is not decreased by an instantaneous elevation of [CO2], but is increased with long-term growth in the field at elevated [CO2]. Plant Physiology 134: 520–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake BG, Azcón-Bieto J, Berry JA, Bunce J, Dijkstra P, Farrar J, Koch GW, Gifford R, Gonzàlez-Meler MA, Lambers H, et al. 1999. Does elevated CO2 inhibit plant mitochondrial respiration in green plants? Plant, Cell and Environment 22: 649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Drake BG, Gonzalez-Meler MA, Long SP. 1997. More efficient plants: a consequence of rising atmospheric CO2? Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 48: 609–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake BG, Meuhe M, Peresta G, Gonzàlez-Meler MA, Matamala R. 1996. Acclimation of photosynthesis, respiration and ecosystem carbon flux of a wetland on Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration. Plant and Soil 187: 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak V, Oplustilova M. 1997. Respiration of woody tissues of Norway spruce in elevated CO2 concentrations. In: Mohren GMJ, Kramer K, Sabate S, eds. Impacts of global change on tree physiology and forest ecosystems. Dordrecht: Klurer Academic Publishers, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- El Kohen A, Pontailler Y, Mousseau M. 1991. Effect d'un doublement du CO2 atmosphérique sur la respiration à l'obscurité des parties aeriennes de jeunes chataigniers (Castanea sativa Mill.). Compte rendue de l'Academie des sciences, serie III 312: 477–481. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti SA, Gonzalez DH. 1998. Carbohydrates modulate the expression of the sunflower cytochrome c gene at the mRNA level. Planta 206: 410–415. [Google Scholar]

- George V, Gerant D, Dizengremel P. 1996. Photosynthesis, Rubisco activity and mitochondrial malate oxidation in pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.) seedlings grown under present and elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Annales des Sciences Forestieres 53: 469–474. [Google Scholar]

- George K, Norby RJ, Hamilton JG, DeLucia EH. 2003. Fine-root respiration in a loblolly pine and sweetgum forest growing in elevated CO2 New Phytologist 160: 511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardina CP, Ryan MG. 2000. Evidence that decomposition rates of organic carbon in mineral soil do not vary with temperature. Nature 404: 858–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford RM. 1994. The global carbon cycle: a view point on the missing sink. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 21: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford RM. 2003. Plant respiration in productivity models: conceptualization, representation and issues for global terrestrial carbon-cycle research. Functional Plant Biology 30: 171–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzàlez-Meler MA, Siedow JN. 1999. Inhibition of respiratory enzymes by elevated CO2: does it matter at the intact tissue and whole plant levels? Tree Physiology 19: 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzàlez-Meler MA, Taneva L. 2004. Integrated effects of atmospheric CO2 concentration on plant and ecosystem respiration. In: Lambers H, Ribas-Carbo M, eds. Plant respiration. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzàlez-Meler MA, Drake BG, Azcón-Bieto J. 1996. Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide and plant respiration. In: Breymeyer AI, Hall DO, Melillo JM, Ågren GI, eds. Global change: effects on coniferous forests and grasslands. SCOPE, Vol. 56. UK: John Wiley & Sons, 161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzàlez-Meler MA, Giles L, RB Thomas, Siedow JN. 2001. Metabolic regulation of leaf respiration and alternative pathway activity in response to phosphate supply. Plant, Cell and Environment 24: 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzàlez-Meler MA, Ribas-Carbo M, Siedow JN, Drake BG. 1996. Direct inhibition of plant mitochondrial respiration by elevated CO2 Plant Physiology 112: 1349–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KL, Anderson OR, Gastrich MD, Lewis JD, Lin G, Schuster W, Seemann JR, Tissue DT, Turnbull M, Whitehead D. 2001. Plant growth in elevated CO2 alters mitochondrial number and chloroplast fine structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA 98: 2473–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KL, Anderson OR, Tissue DT, Turnbull MH, Whitehead D. 2004. Variations in dark respiration and mitochondrial numbers within needles of Pinus radiata grown in ambient or elevated CO2 partial pressure. Tree Physiology 24: 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KL, Ball JT, Strain BR. 1996. Direct and indirect effects of elevated CO2 on whole-shoot respiration in ponderosa pine seedlings. Tree Physiology 16: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KL, Sims DA, Seemann JR. 1999. Altered night-time CO2 concentration affects growth, physiology and biochemistry of soybean. Plant, Cell and Environment 22: 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KL, Thomas RB, Strain BR. 1993. Effects of nitrogen supply and elevated carbon dioxide on construction cost in leaves of Pinus taeda (L.) seedlings. Oecologia 95: 575–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KL, Winner WE, Strain BR. 1996. Construction cost of loblolly and ponderosa pine leaves grown with varying carbon and nitrogen availability. Plant, Cell and Environment 19: 729–738. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JG, DeLucia EH, George K, Naidu S, Finzi AC, Schlesinger WH. 2002. Forest carbon balance under CO2 Oecologia 131: 250–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JG, Thomas RB, Delucia EH. 2001. Direct and indirect effects of elevated CO2 on leaf respiration in a forest ecosystem. Plant, Cell and Environment 24: 975–982. [Google Scholar]

- Hrubec TC, Robinson JM, Donaldson RP. 1985. Effects of CO2 enrichment and carbohydrate content on the dark respiration of soybeans. Plant Physiology 79: 684–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hungate BA, Holland EA, Jackson RB, Chapin III FS, Mooney HA, Field CB. 1997. The fate of carbon in grasslands under carbon dioxide enrichment. Nature 388: 576–579. [Google Scholar]

- Isdo SB, Kimball BA. 1992. Effects of atmospheric CO2 enrichment on photosynthesis, respiration and growth of sour orange trees. Plant Physiology 99: 341–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke S. 2001. Atmospheric CO2 concentration does not directly affect leaf respiration in bean or poplar. Plant, Cell and Environment 24: 1139–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke S, Krewitt M. 2002. Atmospheric CO2 concentration may directly affect leaf respiration measurement in tobacco, but not respiration itself. Plant, Cell and Environment 25: 641–651. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Geisinger D, Walker R, Newman J, Vose JM, Elliott KJ, Ball T. 1994. Soil pCO2, soil respiration, and root activity in CO2-fumigated and nitrogen-fertilized ponderosa pine. Plant and Soil 165: 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kacser H, Burns JA. 1979. Molecular democracy: who shares control? Biochemical Society Transactions 7: 1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JS, Pregitzer KS, Zak DR, Sober J, Isebrands JG, Dickson RE, Hendrey GR, Karnosky DF. 2001. Fine-root biomass and fluxes of soil carbon in young stands of paper birch and trembling aspen as affected by elevated atmospheric CO2 and tropospheric O3 Oecologia 128: 237–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körner CH, Pelaez-Riedl S, Van Bel AJE. 1995. CO2 responsiveness of plants: a possible link to phloem loading. Plant, Cell and Environment 18: 595–600. [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Rygiewicz PT, Ehleringer JR, Johnson MG, Tingey DT. 2001. Time-dependent responses of soil CO2 efflux components to elevated atmospheric [CO2] and temperature in experimental forest mesocosms. Plant and Soil 229: 259–270. [Google Scholar]

- Matamala R, Schlesinger WH. 2000. Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 on fine-root production and activity in an intact temperate forest ecosystem. Global Change Biology 6: 967–979. [Google Scholar]

- Matamala R, Gonzalez-Meler MA, Jastrow JD, Norby RJ, Schlesinger WH. 2003. Impacts of fine root turnover on forest NPP and soil C sequestration potential. Science 302: 1385–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norby RJ, Hanson PJ, O'Neill EG, Tschaplinski TJ, Weltzin JF, Hansen RA, Cheng WX, Wullschleger SD, Gunderson CA, Edwards NT, et al. 2002. Net primary productivity of a CO2-enriched deciduous forest and the implications for carbon storage. Ecological Applications 12: 1261–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Norby RJ, Wullschleger SD, Gunderson CA, Johnson DW, Ceulemans R. 1999. Tree responses to rising CO2 in field experiments: implications for the future forest. Plant, Cell and Environment 22: 683–714. [Google Scholar]

- Pendall E, Del Grosso S, King JY, LeCain DR, Milchunas DG, Morgan JA, Mosier AR, Ojima DS, Parton WA, Tans PP, et al. 2003. Elevated atmospheric CO2 effects and soil water feedbacks on soil respiration components in a Colorado grassland. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 17: 1046. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Trejo MS. 1981. Mobilization of respiratory metabolism in potato tubers by carbon dioxide. Plant Physiology 67: 514–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinelli P, Loreto F. 2003. (CO2)-C-12 emission from different metabolic pathways measured in illuminated and darkened C-3 and C-4 leaves at low, atmospheric and elevated CO2 concentration. Journal of Experimental Botany 54: 1761–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons TL, Welschen RAM. 2002. Overestimation of respiration rates in commercially available clamp-on leaf chambers. Complications with measurement of net photosynthesis. Plant, Cell and Environment 25: 1367. [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Gifford RM, Kriedemann PE, Wong SC. 1992. A quantitative analysis of dark respiration and carbon content as factors in the growth response of plants to elevated CO2 Australian Journal of Botany 40: 501–513. [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, VanBerkel Y, Baxter R, DenHertog J, Dijkstra P, Gifford RM, Griffin KL, Roumet C, Roy J, Wong SC. 1997. The effect of elevated CO2 on the chemical composition and construction costs of leaves of 27 C-3 species. Plant, Cell and Environment 20: 472–482. [Google Scholar]

- Reuveni J, Gale J, Mayer AM. 1995. High ambient carbon dioxide does not affect respiration by suppressing the alternative cyanide-resistant respiration. Annals of Botany 76: 291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Reuveni J, Gale J, Zeroni M. 1997. Differentiating day from night effects of high ambient [CO2] on the gas exchange and growth of Xanthium strumarium L. exposed to salinity stress. Annals of Botany 80: 539–546.11541793 [Google Scholar]

- Ribas-Carbo M, Berry JA, Yakir D, Giles L, Robinson SA, Lennon AM, Siedow JN. 1995. Electron partitioning between the cytochrome and alternative pathways in plant mitochondria. Plant Physiology 109: 829–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan MG. 1991. Effects of climate change on plant respiration. Ecological Applications 1: 157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, KVR, Oren R, Ellsworth DS, Lai C, Herricks JD, Finzi AC, Richter DD, Katul GG. 2003. Exposure to an enriched CO2 atmosphere alters carbon assimilation and allocation in a pine forest ecosystem. Global Change Biology 9: 1378–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Schimel DS. 1995. Terrestrial ecosystems and the carbon cycle. Global Change Biology 1: 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger WH. 1997.Biogeochemistry: an analysis of global change, 2nd edn. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen W, Noble I, Canadell J, Apps M, Schulze ED, Jarvis PG, Baldocchi D, Ciais P, Cramer W, Ehleringer J, et al. 1998. The terrestrial carbon cycle: implications for the Kyoto protocol. Science 280: 1393–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Tissue DT, Lewis JD, Wullschleger SD, Amthor JS, Griffin KL, Anderson R. 2002. Leaf respiration at different canopy positions in sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) grown in ambient and elevated concentrations of carbon dioxide in the field. Tree Physiology 22: 1157–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjoelker MG, Oleksyn J, Lee TD, Reich PB. 2001. Direct inhibition of leaf dark respiration by elevated CO2 is minor in 12 grassland species. New Phytologist 150: 419–424. [Google Scholar]

- Tjoelker MG, Reich PB, Oleksyn J. 1999. Changes in leaf nitrogen and carbohydrates underlie temperature and CO2 acclimation of dark respiration in five boreal species. Plant, Cell and Environment 22: 767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull MH, Whitehead D, Tissue DT, Schuster WSF, Brown KJ, Griffin KL. 2003. Scaling foliar respiration in two contrasting forest canopies. Functional Ecology 17: 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Valentini R, Matteucci G, Dolman AJ, Schulze ED, Rebmann C, Moors EJ, Granier A, Gross P, Jensen NO, Pilegaard K, et al. 2000. Respiration as the main determinant of carbon balance in European forests. Nature 404: 861–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanoosten JJ, Afif D, Dizengremel P. 1992. Long-term effects of a CO2 enriched atmosphere on enzymes of the primary carbon metabolism of spruce trees. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 30: 541–547. [Google Scholar]

- Wang XZ, Anderson OR, Griffin KL. 2004. Chloroplast numbers, mitochondrion numbers and carbon assimilation physiology of Nicotiana sylvestris as affected by CO2 concentration. Environmental and Experimental Botany 51: 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Will RE, Ceulemans R. 1997. Effects of elevated CO2 concentrations on photosynthesis, respiration and carbohydrate status of coppice Populus hybrids. Physiologia Plantarum 100: 933–939. [Google Scholar]

- Williams ML, Jones DG, Baxter R, Farrar JF. 1992. The effect of enhanced concentrations of atmospheric CO2 on leaf respiration. In: Lambers H, van der Plas LHW, eds. Molecular, biochemical and physiological aspects of plant respiration. The Hague: SPB Academic Publishing, 547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger SD, Norby RJ. 1992. Respiratory cost of leaf growth and maintenance in white oak saplings exposed to atmospheric CO2 enrichment. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 22: 1717–1721. [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger SD, Norby RJ, Gunderson CA. 1992. Growth and maintenance respiration in leaves of Liriodendron tulipifera L. exposed to long-term carbon dioxide enrichment in the field. New Phytologist 121: 515–523. [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger SD, Norby RJ, Hanson PJ. 1995. Growth and maintenance respiration in stems of Quercus alba after four years of CO2 enrichment. Physiologia Plantarum 93: 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger SD, Norby RJ, Hendrix DL 1992. Carbon exchange rates, chlorophyll content, and carbohydrate status of two forest tree species exposed to carbon dioxide enrichment. Tree Physiology 10: 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger SD, Norby RJ, Love JC, Runck C. 1997. Energetic costs of tissue construction in yellow-poplar and white oak trees exposed to long-term CO2 enrichment. Annals of Botany 80: 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger SD, Ziska LH, Bunce JA. 1994. Respiratory response of higher plants to atmospheric CO2 enrichment. Physiologia Plantarum 90: 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zak DR, Pregitzer KS, King JS, Holmes WE. 2000. Elevated atmospheric CO2, fine roots and the response of soil microorganisms: a review and hypothesis. New Phytologist 147: 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ziska LH, Bunce JA. 1998. The influence of increasing growth temperature and CO2 concentration on the ratio of respiration to photosynthesis in soybean seedlings. Global Change Biology 4: 637–643. [Google Scholar]

- Ziska, LH, Bunce JA. 1999. Effects of elevated carbon dioxide concentration at night on the growth and gas exchange of selected C4 species. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 26: 71–77. [Google Scholar]