Abstract

Background:

We studied the relationships among psychiatrist supply, practice patterns, and access to psychiatrists in Ontario Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs) with differing levels of psychiatrist supply.

Methods:

We analyzed practice patterns of full-time psychiatrists (n = 1379) and postdischarge care to patients who had been admitted to hospital for psychiatric care, according to LHIN psychiatrist supply in 2009. We measured the characteristics of psychiatrists' patient panels, including sociodemographic characteristics, outpatient panel size, number of new patients, inpatient and outpatient visits per psychiatrist, and percentages of psychiatrists seeing fewer than 40 and fewer than 100 unique patients. Among patients admitted to hospital with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression (n = 21,123), we measured rates of psychiatrist visits, readmissions, and visits to the emergency department within 30 and 180 days after discharge.

Results:

Psychiatrist supply varied from 7.2 per 100 000 residents in LHINs with below-average supply to 62.7 per 100 000 in the Toronto Central LHIN. Population-based outpatient and inpatient visit rates and psychiatric admission rates increased with LHIN psychiatrist supply. However, as the supply of psychiatrists increased, outpatient panel size for full-time psychiatrists decreased, with Toronto psychiatrists having 58% smaller outpatient panels and seeing 57% fewer new outpatients relative to LHINs with the lowest psychiatrist supply. Similar patterns were found for inpatient practice. Moreover, as supply increased, annual outpatient visit frequency increased: the average visit frequency was 7 visits per outpatient for Toronto psychiatrists and 3.9 visits per outpatient in low-supply LHINs. One-quarter of Toronto psychiatrists and 2% of psychiatrists in the lowest-supply LHINs saw their outpatients more than 16 times per year. Of full-time psychiatrists in Toronto, 10% saw fewer than 40 unique patients and 40% saw fewer than 100 unique patients annually; the corresponding proportions were 4% and 10%, respectively, in the lowest-supply LHINs. Overall, follow-up visits after psychiatric discharge were low, with slightly higher rates in LHINs with a high psychiatrist supply.

Interpretation:

Full-time psychiatrists who practised in Ontario LHINs with high psychiatrist supply saw fewer patients, but they saw those patients more frequently than was the case for psychiatrists in low-supply LHINs. Increasing the supply of psychiatrists while funding unlimited frequency and duration of psychotherapy care may not improve access for patients who need psychiatric services.

Primary care physicians have difficulty accessing psychiatrists in many jurisdictions.1–5 In a US survey of primary care physicians, 66% reported that they could not arrange for their patients with mental health problems to be seen by psychiatrists, a rate double that for other specialties.6 In Canada, 35% of family doctors rated access to psychiatrists as poor, compared with 4% for access to internal medicine specialists and 2% for access to pediatricians.7 These data were corroborated by a recent Vancouver study, in which only 6 of 230 psychiatrists were able to provide a timely consultation for a patient referred by a primary care physician,8 and a US study showing that psychiatrists were less likely than other specialists to accept patients with insurance coverage, including Medicare and Medicaid,9 compared to private pay.

Poor access to psychiatrists could lead to the conclusion that there are not enough psychiatrists to meet the needs of the population. On the basis of a systematic model, the Canadian Psychiatric Association recommended a supply of 15 psychiatrists per 100 000 residents,10 which would represent an increase over the 2011 supply of 13.9 psychiatrists per 100 000 in Canada11 or the 2009 supply of 13.5 per 100 000 in the United States.12 However, these national rates conceal large variations across regions. Typically, there are fewer psychiatrists per capita in rural settings.13 In Ontario, a rural psychiatrist shortage has persisted for nearly 2 decades.14,15 These regional variations in Ontario provide a unique opportunity to study the effect of psychiatrist supply on practice in an environment where universal access, including access to care provided by psychiatrists, is provided by a governmentfunded health insurance program.

The objective of this study was to measure the relationships among psychiatrist supply, practice patterns, and access to psychiatrists in Ontario regions with differing psychiatrist supply. We hypothesized that patients in regions with higher psychiatrist supply would have better access to care and more timely care after psychiatric discharge.

Methods

Overview.

The 2009 population of Ontario (13 072 716) was organized into 14 health regions or Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs). We measured psychiatrist supply and service utilization in these 14 LHINs. We examined the practice patterns of full-time psychiatrists and measured postdischarge care provided by psychiatrists to patients who were admitted to hospital for psychiatric care in 2009.

Data sources.

We calculated psychiatrist supply from the physician specialty and practice location variables in the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences Physician Database. Using unique, anonymized, encrypted identifiers, we linked patient records across multiple Ontario health administrative databases containing information on all publicly insured, medically necessary hospital and physician services. We used the following databases: the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) for physician billings for physician visits and consultations, which lists diagnosis codes and the location of each visit (and in which, for psychotherapy or psychiatric care visits, psychiatrists can bill for units of time spent with the patient, where 1 "unit" is 20–45 minutes, 2 units is 46–79 minutes, and 3 units is 80–115 minutes); the Discharge Abstract Database for non–mental health hospital admissions, which includes the most responsible diagnosis in relation to patient length of stay; the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System for all admissions to mental health–designated hospital beds, which includes the most responsible diagnosis; the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System for emergency department visits; and the Registered Persons Database for patient demographic information and deaths. Neighbourhood income was derived from Statistics Canada 2001 census estimates.

Regional characteristics.

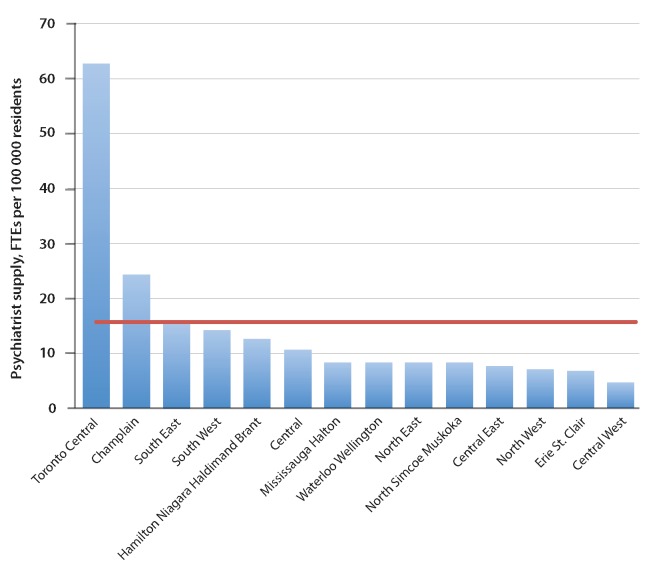

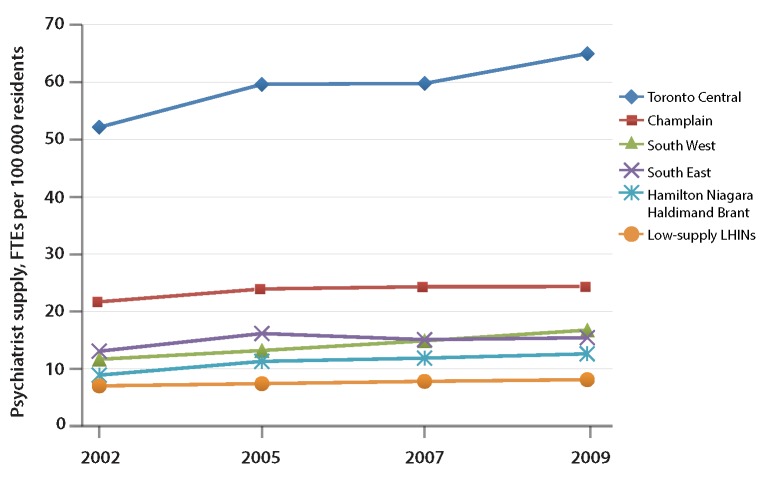

The LHINs for Toronto Central, Champlain (Ottawa area), South West (London area), South East (Kingston area), and Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant (referred to hereafter as Hamilton) each represent large urban centres with established academic psychiatry departments within medical schools. These 5 LHINs have the largest fulltime equivalent (FTE) psychiatrist supply (Fig. 1). We aggregated the 9 remaining LHINs into a "low-supply" group. Per capita FTE psychiatrist supply has been stable over the past 8 years across these regions, except for large absolute increases that have occurred in the Toronto Central LHIN (Fig. 2), so we analyzed patterns during 2009.

Figure 1.

Supply of psychiatrists in each Ontario Local Health Integration Network. FTEs = full-time equivalents. The red line indicates the mean per capita psychiatrist supply for the province.

Figure 2.

Trends in psychiatrist supply in Ontario from 2002 to 2009. FTEs = full-time equivalents, LHINs = Local Health Integration Networks.

As a crude proxy for service need, we computed regional rates of hospital admission for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) codes for hospital admissions captured in the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (schizophrenia, 295.x; bipolar disorder, 296.x except 296.2 and 296.3; major depression, 296.2 and 296.3) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes for psychiatric hospital admissions captured in the Discharge Abstract Database (schizophrenia, F20 and F25; bipolar affective disorder, F30 and F31; major depression, F32 and F33). These 3 diagnoses account for 80% of all psychiatric admissions in general hospital settings and 60% of all admissions in specialty hospital settings, the lower rate in the specialty hospital setting being due to the larger proportion of addiction-related admissions.16 Follow-up psychiatric visits within 30 days after discharge from hospital is a measure of access to care following psychiatric admissions and serves as a performance indicator in Ontario (Health Quality Ontario)17 and other jurisdictions.18

Characteristics of patient panels of full-time psychiatrists.

We defined full-time psychiatrists as those with a valid billing number whose income from annual billings (April 2009 to March 2010) was above the 30th percentile for all Ontario psychiatrists, to conform with the Health Canada definition of an FTE physician.19 For each full-time psychiatrist, we measured the size of the outpatient panel, the number of new outpatients, and the number of patient visits, both overall and by location (inpatient v. outpatient). New patients were defined as those with no visits to the same psychiatrist in the preceding 12 months. We created 3 categories for mean annual outpatient visit frequency: < 4 visits/ year, reflecting typical consultant practice; 4–16 visits/ year, reflecting typical continuing care or an episode of acute care with pharmacotherapy or evidence-based psychotherapy during 8–16 sessions; and > 16 visits/ year, reflecting long-term psychotherapy practice. For psychotherapy, we recorded the time spent per visit. A patient seen by more than one psychiatrist during the 12-month period was assigned to one psychiatrist's panel according to highest visit frequency.

For each outpatient, we recorded age, sex, income (based on neighbourhood-level income quintiles), visit frequency, and psychiatric and nonpsychiatric hospital admissions in the 2 years before the first visit date in 2009. Psychiatric hospital admissions, excluding admissions for delirium and dementia (DSM-IV codes 293, 780, 290, 294, and V-codes; ICD codes F00 to F09), were used as a proxy for severity of illness.

Outcomes after psychiatric hospital admissions.

In a separate population-based analysis, we examined follow-up care for adults who had been admitted to hospital with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression between 1 April 2009 and 31 March 2010. For each patient, we recorded the first admission within each diagnostic category. We measured follow-up visits with a psychiatrist, visits to the emergency department, and cause-specific readmissions within 30 and 180 days following discharge.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as counts, means, and percentages with standard deviations. We used weighted regression, with weighting by regional population, to test for trends in visit and admission rates and full-time psychiatrist practice characteristics according to regional supply. Unless specified, all analyses were significant at p < 0.001. We replicated our results for 1 April 2008 to 31 March 2009 to assess the consistency of our findings.

Ethics approval.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto.

Results

Regional psychiatrist supply, patients, and psychiatric disease burden.

The overall psychiatrist supply in Ontario in 2009 was 15.7 psychiatrists per 100 000 residents. Per capita psychiatrist FTE supply across LHINs ranged from 7.2 per 100 000 individuals in low-supply LHINs to 62.7 per 100 000 individuals in the Toronto Central LHIN (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Population-based psychiatrist supply, outpatient and inpatient visit rates, and psychiatric admission rates for calendar year 2009, by Ontario Local Health Integration Network (LHIN)

| Variable | LHIN | p value for test for trend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto Central | Champlain | South West | South East | Hamilton* | Low-supply LHINs | ||

| Population | 1 143 640 | 1 230 939 | 950 611 | 487 888 | 1 395 337 | 7 864 301 | |

| No. of psychiatrists | 717 | 291 | 135 | 71 | 162 | 568 | |

| No. of psychiatrists per 100 000 | 62.7 | 23.6 | 14.2 | 14.6 | 11.6 | 7.2 | 0.028 |

| No. of inpatient visits per 1000 | 117.1 | 63.9 | 35.1 | 36.3 | 37.9 | 31.5 | 0.029 |

| No. of outpatient visits per 1000 | 634.6 | 237.7 | 152.9 | 100.4 | 119.8 | 95.0 | 0.044 |

| No. of psychiatric admissions per 100 000 | |||||||

| Schizophrenia | 167.2 | 85.5 | 75.1 | 86.3 | 66.3 | 64.3 | 0.05 |

| Bipolar disorder | 62.8 | 47.3 | 66.0 | 50.8 | 59.1 | 48.9 | 0.24 |

| Major depression | 76.8 | 70.6 | 80.8 | 72.8 | 74.4 | 76.8 | 0.61 |

Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant.

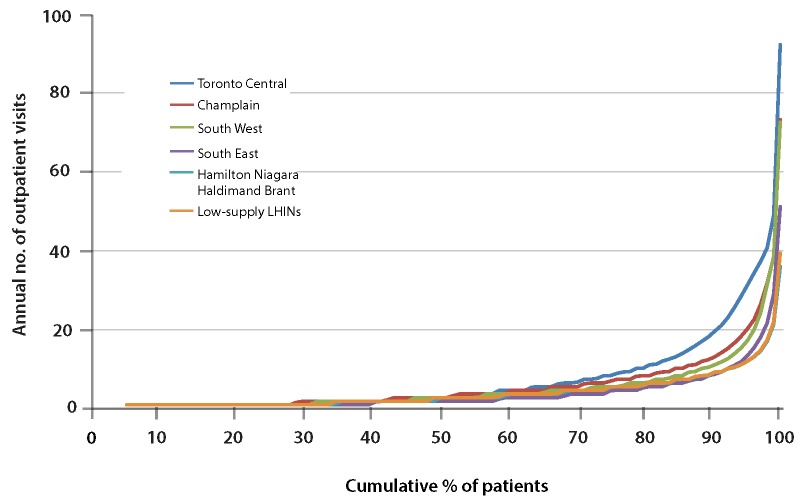

Population-based rates for inpatient and outpatient visits displayed a gradient associated with supply and were 4- to 7-fold higher in the Toronto Central LHIN than in low-supply LHINs (Table 1). The hospital admission rate for schizophrenia was 2.6-fold higher in Toronto than in low-supply LHINs, but there was little variation in admission rates for bipolar disorder and major depression (Table 1). A Lorenz curve displaying the cumulative distribution of annual number of outpatient visits as a function of the proportion of patients receiving those visits, among patients who received at least 1 outpatient visit (Figure 3), showed that in Toronto, 10% of patients had 20 or more outpatient visits per year, whereas less than 2% of patients in Hamilton and low-supply LHINs had this rate of outpatient visits.

Figure 3.

Lorenz curve showing cumulative distribution of annual number of outpatient visits as a function of the proportion of patients receiving those visits, for patients who received at least 1 outpatient visit, according to Ontario Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs).

Full-time psychiatrists: outpatient characteristics.

The characteristics of outpatient panels of full-time psychiatrists were similar across LHINs, except that patients in the Toronto Central LHIN were more likely to be in the highest income quintile and less likely to have prior psychiatric or nonpsychiatric hospital admissions relative to patients in low-supply LHINs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of outpatient panels of full-time psychiatrists, by Ontario Local Health Integration Network (LHIN)

| Characteristic | LHIN; no. (%) of patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto Central | Champlain | South West | South East | Hamilton | Low-supply LHINs | |

| No. of outpatients | 76 403 | 38 763 | 22 307 | 9 169 | 31 806 | 153 943 |

| Sex, female | 41 977 (54.9) | 22 136 (57.1) | 11 822 (53.0) | 46777 (51.0) | 17 660 (55.5) | 83 443 (54.2) |

| Age, yr | ||||||

| < 17 | 6 053 (7.9) | 1 944 (5.0) | 3 300 (14.8) | 745 (8.1) | 2 288 (7.2) | 16 932 (11.0) |

| 18–29 | 12 453 (16.3) | 5 814 (15.0) | 4 698 (21.1) | 1 629 (17.8) | 5 446 (17.1) | 23 473 (15.2) |

| 30–39 | 12 510 (16.4) | 5 801 (15.0) | 3 725 (16.7) | 1 462 (15.9) | 5 445 (17.1) | 23 248 (15.1) |

| 40–49 | 15 610 (20.4) | 8 034 (20.7) | 4 320 (19.4) | 2 010 (21.9) | 6 709 (21.1) | 32 853 (21.3) |

| 50–64 | 20 420 (26.7) | 10 506 (27.1) | 4 653 (20.9) | 2 520 (27.5) | 7 940 (25.0) | 40 200 (26.1) |

| > 64 | 9 357 (12.2) | 6 664 (17.2) | 1 611 (7.2) | 803 (8.8) | 3 978 (12.5) | 17 237 (11.2) |

| Income quintile | ||||||

| Missing | 643 (0.8) | 265 (0.7) | 174 (0.8) | 131 (1.4) | 248 (0.8) | 665 (0.4) |

| 1 (lowest) | 16 607 (21.7) | 8 102 (20.9) | 5 778 (25.9) | 2 552 (27.8) | 8 441 (26.5) | 35 912 (23.3) |

| 2 | 13 420 (17.6) | 8 092 (20.9) | 4 863 (21.8) | 1 856 (20.2) | 6 817 (21.4) | 31 019 (20.1) |

| 3 | 12 089 (15.8) | 7 068 (18.2) | 4 319 (19.4) | 1 706 (18.6) | 5 733 (18.0) | 29 517 (19.2) |

| 4 | 13 337 (17.5) | 7 867 (20.3) | 3 832 (17.2) | 1 510 (16.5) | 5 348 (16.8) | 29 797 (19.4) |

| 5 (highest) | 20 307 (26.6) | 7 369 (19.0) | 3 341 (15.0) | 1 414 (15.4) | 5 219 (16.4) | 27 033 (17.6) |

| Psychiatric admission in previous 2 yr* | ||||||

| Total | 4 239 (5.5) | 2 621 (6.8) | 1 618 (7.3) | 624 (6.8) | 2 534 (8.0) | 11 597 (7.5) |

| For schizophrenia | 1 142 (1.5) | 625 (1.6) | 227 (1.0) | 96 (1.0) | 421 (1.3) | 2 357 (1.5) |

| For bipolar disorder | 612 (0.8) | 405 (1.0) | 281 (1.3) | 87 (0.9) | 496 (1.6) | 2 043 (1.3) |

| For depression | 853 (1.1) | 488 (1.3) | 330 (1.5) | 103 (1.1) | 509 (1.6) | 2 555 (1.7) |

| Any hospital admission in previous 2 yr | 10 606 (13.9) | 5 986 (15.4) | 3 277 (14.7) | 1 256 (13.7) | 5 553 (17.5) | 23 445 (15.2) |

Excluding admissions for dementia and delirium.

Full-time psychiatrists: practice characteristics.

Between 45% and 68% of full-time psychiatrists had inpatient billings (Table 3). Higher-supply LHINs had a smaller percentage of psychiatrists with any inpatient billings and lower numbers of inpatient visits per psychiatrist than lower-supply LHINs. As psychiatrist supply increased, the size of full-time psychiatrists' outpatient panels decreased, with Toronto psychiatrists having 58% smaller outpatient panels and seeing 57% fewer new outpatients relative to LHINs with the lowest psychiatrist supply. However, Toronto psychiatrists, on average, saw their patients 30%–80% more frequently than the rest of the province: 21% of Toronto psychiatrists v. 50% of those in low-supply LHINs saw their patients fewer than 4 times per year, whereas 24% of Toronto psychiatrists v. 2% of those in low-supply LHINs saw their patients more than 16 times per year. Regional visit frequencies showed a gradient reflecting supply. There was a similar pattern for the duration of outpatient visits: 15% of Toronto psychiatrists v. 47% of those in low-supply LHINs had an average visit duration between 20 and 45 minutes, whereas 12% of Toronto psychiatrists and 7% of those in low-supply LHINs had an average visit duration greater than 79 minutes. A substantial proportion of full-time psychiatrists in the Toronto Central, Champlain, and South West LHINs had practices consisting of fewer than 40 outpatients or fewer than 100 outpatients (Toronto Central, 10% and 40%; Champlain, 7% and 28%; South West, 8% and 24%; low-supply LHINs, 4% and 10%, respectively).

Table 3.

Practice characteristics for full-time psychiatrists, by Ontario Local Health Integration Network (LHIN)

| Characteristic | LHIN; no. (%) of psychiatrists or mean value ± SD | p value for test for trend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto Central | Champlain | South West | South East | Hamilton | Low-supply LHINs | ||

| Total no. of psychiatrists, full-time + part-time | 717 | 291 | 135 | 71 | 162 | 568 | |

| No. (%) of full-time psychiatrists* | 523 (73) | 218 (75) | 83 (61) | 34 (48) | 102 (63) | 419 (74) | |

| No. (%) of full-time psychiatrists with inpatient billings† | 251 (48) | 112 (51) | 37 (45) | 19 (56) | 69 (68) | 274 (65) | 0.009 |

| No. of inpatients seen, mean ± SD | 49 ± 98 | 46 ± 83 | 75 ± 127 | 76 ± 142 | 92 ± 134 | 111 ± 133 | 0.08 |

| Annual no. of inpatient visits,‡ mean ± SD | 240 ± 517 | 351 ± 647 | 366 ± 643 | 493 ± 1040 | 501 ± 845 | 573 ± 772 | 0.006 |

| Outpatient panel, mean ± SD | |||||||

| Size of outpatient panel‡ | 181 ± 177 | 211 ± 188 | 311 ± 340 | 300 ± 335 | 360 ±286 | 431 ± 346 | 0.009 |

| New outpatients enrolled‡ | 105 ± 134 | 110 ± 125 | 174 ± 261 | 186 ± 256 | 206 ±158 | 244 ± 261 | 0.036 |

| Annual no. of outpatient visits‡ | 1275 ± 735 | 1245 ± 732 | 1618 ± 1588 | 1148 ± 679 | 1432 ±1263 | 1696 ± 1104 | 0.17 |

| No. of visits/outpatient per psychiatrist§ | 7.0 ± 92 | 5.9 ± 81 | 5.2 ± 111 | 3.8 ± 66 | 4.0 ± 45 | 3.9 ± 52 | 0.039 |

| Outpatient visit frequency, no. (%) of psychiatrists | |||||||

| < 4 visits/yr | 112 (21) | 62 (28) | 33 (40) | 18 (53) | 62 (61) | 210 (50) | 0.009 |

| 4–16 visits/yr | 283 (54) | 127 (58) | 35 (42) | 14 (41) | 37 (36) | 199 (47) | 0.16 |

| > 16 visits/yr | 128 (24) | 29 (13) | 15 (18) | ≤ 5|| | ≤ 5|| | 10 (2) | 0.005 |

| Mean outpatient visit duration, % of psychiatrists ¶ | |||||||

| 20–45 min | 15 | 24 | 35 | 30 | 58 | 47 | 0.004 |

| 46–79 min | 73 | 64 | 53 | 61 | 35 | 45 | 0.005 |

| >79 min | 12 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 0.002 |

| Outpatient panel size, no. (%) of psychiatrists** | |||||||

| < 40 | 50 (10) | 16 (7) | 7 (8) | ≤ 5|| | ≤ 5|| | 15 (4) | 0.010 |

| < 100 | 208 (40) | 60 (28) | 20 (24) | ≤ 5|| | 15 (15) | 42 (10) | 0.002 |

SD = standard deviation.

In this row, the proportion of full-time psychiatrists in each LHIN was calculated as the percentage of all psychiatrists in the LHIN.

In this row, the proportion of full-time psychiatrists with inpatient billings in each LHIN was calculated as the percentage of all full-time psychiatrists in the LHIN.

All rates are per psychiatrist, except time per visit, which is calculated per time-based outpatient visit.

The number of visits per patient per psychiatrist was calculated as a weighted mean.

To protect privacy, exact values are not given if value was 5 or below.

The visit duration was calculated as a weighted mean among all psychiatrists.

Psychiatrists with inpatient visits accounting for 50% or more of total annual visits were excluded from this calculation.

Outpatient characteristics by visit frequency.

In the Toronto Central, Champlain, and South West LHINs, 8.3%, 3.5% and 4.8%, respectively, of patients were seen more than 16 times per year, compared with 0.3% of patients in low-supply LHINs (Table 4). In all LHINs, patients seen frequently were more likely to have higher incomes and less likely to have a prior psychiatric admission.

Table 4.

Characteristics of patient panels for full-time psychiatrists, by mean outpatient visit frequency, according to Ontario Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs)

| Outpatient visit frequency; no. (%) of outpatients* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | < 4/yr | 4–16/yr | > 16/yr |

| Toronto Central LHIN (n = 76 403) | |||

| No. of outpatients (% of total) | 29 363 (38.4) | 40 734 (53.3) | 6 306 (8.3) |

| Sex, female | 15 351 (52.3) | 22 627 (55.6) | 3 999 (63.4) |

| Income quintile | |||

| Missing | 277 (0.9) | 332 (0.8) | 34 (0.5) |

| 1 (lowest) | 6 907 (23.5) | 8 879 (21.8) | 821 (13.0) |

| 2 | 5 760 (19.6) | 6 874 (16.9) | 786 (12.5) |

| 3 | 4 969 (16.9) | 6 301 (16.5) | 819 (13.0) |

| 4 | 5 170 (17.6) | 7 099 (17.4) | 1 068 (16.9) |

| 5 (highest) | 6 280 (21.4) | 11 249 (27.6) | 2 778 (44.1) |

| Psychiatric admission in previous 2 yr † | 1 680 (5.7) | 2 479 (6.1) | 80 (1.3) |

| Any hospital admission in previous 2 yr | 4 893 (16.7) | 5 391 (13.2) | 322 (5.1) |

| Champlain LHIN (n = 38 763) | |||

| No. of outpatients (% of total) | 14 722 (38.0) | 22 685 (58.5) | 1 356 (3.5) |

| Sex, female | 8 522 (57.9) | 12 796 (56.4) | 818 (60.4) |

| Income quintile | |||

| Missing | 67 (0.5) | 196 (0.9) | ≤ 5‡ NA |

| 1 (lowest) | 3 260 (22.1) | 4 673 (20.6) | 169 (12.5) |

| 2 | 3 113 (21.1) | 4 741 (20.9) | 238 (17.6) |

| 3 | 2 621 (17.8) | 4 203 (18.5) | 244 (18.0) |

| 4 | 3 057 (20.8) | 4 513 (19.9) | 297 (21.9) |

| 5 | 2 604 (17.7) | 4 359 (19.2) | 406 (29.9) |

| Psychiatric admission in previous 2 yr † | 1 163 (7.9) | 1 445 (6.4) | 13 (1.0) |

| Any hospital admission in previous 2 yr | 3 008 (20.4) | 2 917 (12.9) | 61 (4.5) |

| South West LHIN (n = 22 307) | |||

| No. of outpatients (% of total) | 13 886 (62.2) | 7 349 (32.9) | 1 072 (4.8) |

| Sex, female | 7 131 (51.4) | 4 091 (55.7) | 600 (56.0) |

| Income quintile | |||

| Missing | 111 (0.8) | 53 (0.7) | 10 (0.9) |

| 1 (lowest) | 3 633 (26.2) | 1 840 (25.0) | 305 (28.5) |

| 2 | 3 137 (22.6) | 1 506 (20.5) | 220 (20.5) |

| 3 | 2 705 (19.5) | 1 423 (19.4) | 191 (17.8) |

| 4 | 2 262 (16.3) | 1 398 (19.0) | 172 (16.0) |

| 5 (highest) | 2 038 (14.7) | 1 129 (15.4) | 174 (16.2) |

| Psychiatric admission in previous 2 yr † | 1 077 (7.8) | 524 (7.1) | 17 (1.6) |

| Any hospital admission in previous 2 yr | 2 256 (16.2) | 937 (12.8) | 84 (7.8) |

| South East LHIN (n = 9169) | |||

| No. of outpatients (% of total) | 6 318 (68.9) | 2 717 (29.6) | 134 (1.5) |

| Sex, female | 2 941 (46.5) | 1 636 (60.2) | 100 (74.6) |

| Income quintile | |||

| Missing | 120 (1.9) | 10 (0.4) | ≤ 5‡ NA |

| 1 (lowest) | 1 817 (28.8) | 703 (25.9) | 32 (23.9) |

| 2 | 1 318 (20.9) | 515 (19.0) | 23 (17.2) |

| 3 | 1 150 (18.2) | 538 (19.8) | 18 (13.4) |

| 4 | 1 027 (16.3) | 461 (17.0) | 22 (16.4) |

| 5 (highest) | 886 (14.0) | 490 (18.0) | 38 (28.4) |

| Psychiatric admission in previous 2 yr † | 463 (7.3) | 156 (5.7) | ≤ 5‡ NA |

| Any hospital admission in previous 2 yr | 873 (13.8) | 370 (13.6) | 13 (9.7) |

| Hamilton LHIN (n = 31 806) | |||

| No. of outpatients (% of total) | 20 036 (63.0) | 11 527 (36.2) | 243 (0.8) |

| Sex, female | 10 875 (54.3) | 6 665 (57.8) | 120 (49.4) |

| Income quintile | |||

| Missing | 116 (0.6) | 132 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| 1 (lowest) | 5 172 (25.8) | 3 245 (28.2) | 24 (9.9) |

| 2 | 4 382 (21.9) | 2 395 (20.8) | 40 (16.5) |

| 3 | 3 611 (18.0) | 2 082 (18.1) | 40 (16.5) |

| 4 | 3 433 (17.1) | 1 861 (16.1) | 54 (22.2) |

| 5 (highest) | 3 322 (16.6) | 1 812 (15.7) | 85 (35.0) |

| Psychiatric admission in previous 2 yr † | 1 595 (8.0) | 934 (8.1) | ≤ 5‡ NA |

| Any hospital admission in previous 2 yr | 3 501 (17.5) | 2 040 (17.7) | 12 (4.9) |

| Low-supply LHINs (n = 153 943) | |||

| No. of outpatients (% of total) | 92 895 (60.3) | 60 524 (39.3) | 524 (0.3) |

| Sex, female | 47 847 (51.5) | 35 271 (58.3) | 325 (62.0) |

| Income quintile | |||

| Missing | 478 (0.5) | 187 (0.3) | 0 (0) |

| 1 (lowest) | 22 412 (24.1) | 13 447 (22.2) | 53 (10.1) |

| 2 | 19 031 (20.5) | 11 934 (19.7) | 54 (10.3) |

| 3 | 17 947 (19.3) | 11 486 (19.0) | 84 (16.0) |

| 4 | 17 574 (18.9) | 12 093 (20.0) | 130 (24.8) |

| 5 (highest) | 15 453 (16.6) | 11 377 (18.8) | 203 (38.7) |

| Psychiatric admission in previous 2 yr † | 7 215 (7.8) | 4 377 (7.2) | ≤ 5‡ NA |

| Any hospital admission in previous 2 yr | 14 916 (16.1) | 8 493 (14.0) | 36 (6.9) |

NA = not applicable.

For each LHIN, the percentages across the first row (no. [%] of outpatients) are calculated from the total number of outpatients for that LHIN. For subsequent rows in each LHIN, the percentages in each column are calculated from the number of outpatients in that column (i.e., visit category).

Excluding admissions for dementia and delirium.

To protect privacy, exact values are not given if value was 5 or below.

Follow-up after discharge from psychiatric admission.

Among patients admitted to hospital for a psychiatric condition, 21.0%–67.2% were seen by a psychiatrist within 30 days after discharge (Table 5). The likelihood of a follow-up visit with a psychiatrist within 30 and 180 days after discharge was higher in the Toronto Central and Champlain LHINs than in the other LHINs. The proportion of discharged patients with emergency department visits within 30 or 180 days was similar across LHINs, but the proportion readmitted for the same diagnosis within 30 or 180 days was higher in the Toronto Central LHIN than in other LHINs. In a secondary analysis including visits not only to psychiatrists but also to primary care physicians and general internal medicine specialists, postadmission follow-up visit rates were more similar. Thirty-day follow-up rates by any physician for schizophrenia ranged from 74% (Champlain) to 69% (low-supply LHINs); for bipolar disorder, from 84% (Toronto Central) to 65% (South West); and for depression, from 84% (Toronto Central) to 70% (South West). These findings suggest that nonpsychiatrists are more involved in postadmission care in LHINs with lower psychiatrist supply.

Table 5.

Access to care and outcomes following discharge after psychiatric hospital admission, by Ontario Local Health Integration Network (LHIN)

| LHIN; no. (%) of patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Toronto Central | Champlain | South West | South East | Hamilton | Low-supply LHINs |

| Schizophrenia | ||||||

| No. of patients | 1291 | 727 | 523 | 295 | 669 | 3649 |

| Psychiatrist visit after discharge | ||||||

| Within 30 days | 722 (55.9) | 446 (61.3) | 150 (28.7) | 62 (21.0) | 293 (43.8) | 1663 (45.6) |

| Within 180 days | 1038 (80.4) | 618 (85.0) | 242 (46.3) | 131 (44.4) | 496 (74.1) | 2531 (69.4) |

| Emergency department visit after discharge | ||||||

| Within 30 days | 337 (26.1) | 141 (19.4) | 88 (16.8) | 68 (23.1) | 103 (15.4) | 735 (20.1) |

| Within 180 days | 671 (52.0) | 341 (46.9) | 244 (46.7) | 150 (50.8) | 303 (45.3) | 1719 (47.1) |

| Psychiatric readmission after initial discharge | ||||||

| Within 30 days | 219 (17.0) | 92 (12.7) | 61 (11.7) | 46 (15.6) | 61 (9.1) | 504 (13.8) |

| Within 180 days | 504 (39.0) | 235 (32.3) | 179 (34.2) | 107 (36.3) | 203 (30.3) | 1220 (33.4) |

| Bipolar disorder | ||||||

| No. of patients | 549 | 468 | 505 | 199 | 672 | 3125 |

| Psychiatrist visit after discharge | ||||||

| Within 30 days | 369 (67.2) | 284 (60.7) | 186 (36.8) | 88 (44.2) | 374 (55.7) | 1544 (49.4) |

| Within 180 days | 476 (86.7) | 389 (83.1) | 306 (60.6) | 127 (63.8) | 549 (81.7) | 2723 (87.1) |

| Emergency department visit after discharge | ||||||

| Within 30 days | 135 (24.6) | 99 (21.2) | 110 (21.8) | 53 (26.6) | 154 (22.9) | 702 (22.5) |

| Within 180 days | 269 (49.0) | 229 (48.9) | 262 (51.9) | 101 (50.8) | 327 (48.7) | 1575 (50.4) |

| Psychiatric readmission after initial discharge | ||||||

| Within 30 days | 100 (18.2) | 57 (12.2) | 67 (13.3) | 32 (16.1) | 69 (10.3) | 364 (11.6) |

| Within 180 days | 195 (35.5) | 122 (26.1) | 157 (31.1) | 56 (28.1) | 193 (28.7) | 825 (26.4) |

| Depression | ||||||

| No. of patients | 735 | 703 | 662 | 304 | 885 | 5162 |

| Psychiatrist visit after discharge | ||||||

| Within 30 days | 447 (60.8) | 402 (57.2) | 252 (38.1) | 94 (30.9) | 470 (53.1) | 2281 (44.2) |

| Within 180 days | 584 (79.5) | 529 (75.2) | 408 (61.6) | 162 (53.3) | 669 (75.6) | 3463 (67.1) |

| Emergency department visit after discharge | ||||||

| Within 30 days | 138 (18.8) | 132 (18.8) | 121 (18.3) | 54 (17.8) | 169 (19.1) | 1071 (20.7) |

| Within 180 days | 320 (43.5) | 311 (44.2) | 322 (48.6) | 130 (42.8) | 429 (48.5) | 2540 (49.2) |

| Psychiatric readmission after initial discharge | ||||||

| Within 30 days | 77 (10.5) | 61 (8.7) | 55 (8.3) | 29 (9.5) | 68 (7.7) | 428 (8.3) |

| Within 180 days | 185 (25.2) | 137 (19.5) | 133 (20.1) | 58 (19.1) | 192 (21.7) | 1042 (20.2) |

Sensitivity analysis.

The analyses using data from 1 April 2008 to 31 March 2009 yielded results similar to those obtained for 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2010.

Interpretation

In LHINs with higher supply, psychiatrists saw fewer inpatients and outpatients, and they enrolled fewer new outpatients per year, but they saw their patients more

frequently and for longer visits. Patients who were seen more frequently were wealthier and less likely to have had a prior psychiatric hospital admission, consistent with previous observations of inequities in psychiatrist access in Ontario20,21 and with socioeconomic gradients in access to primary care in Ontario.22 The majority of psychiatrists in all LHINs saw patients, on average, up to 16 times per year, a visit frequency that is consistent with providing consultations, pharmacotherapy, or evidence-based psychotherapy. However, in the highsupply LHINs of Toronto Central, Champlain, and South West, 7%–10% of full-time psychiatrists saw fewer than 40 unique patients per year, compared with less than 4% in the rest of the province. Similarly, 24%–40% of full-time psychiatrists in these high-supply LHINs saw fewer than 100 unique patients per year, compared to less than 15% in the rest of the province. This pattern of a small number of patients seen frequently is consistent with the provision of long-term psychotherapy. Although there was a higher likelihood of being seen by a psychiatrist following psychiatric hospital admission in the Toronto Central and Champlain LHINs, the differences were not large, considering the vastly higher supply of psychiatrists in these LHINs.

Overall, we found a high level of variability in practice patterns across Ontario LHINs associated with a differing supply of psychiatrists. Our data do not provide a direct causal explanation for these findings. In Ontario, psychiatrists are the only mental health professionals whose services are eligible for reimbursement by the publicly funded health insurance program. Ontario psychiatrists are generally reimbursed for patient care on a fee-for-service basis. The Ontario fee schedule, similar to that of other Canadian provinces, provides payments for consultations, which are onetime assessments with the purpose of providing diagnostic and management suggestions to the referring physician. However, psychiatrists can also use timebased fee codes to provide ongoing care at rates similar to consultation billings. These time-based fee codes permit psychiatrists to provide ongoing mental health care, including psychotherapy, without a limit on the duration of visits or their frequency, regardless of the acuity or complexity of the patients being seen. Thus, a proportion of psychiatrists may elect to provide care to a small number of patients whose care is relatively easy to manage and who reliably show up for their appointments, since this is easier than providing consultations or acute care to seriously ill, unstable patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or severe depression.

In the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, the role of a psychiatrist has been modified to prevent this pattern of practice and to improve access to psychiatrists for patients with severe mental illness. In these countries, reimbursement for psychiatric consultations is higher than for psychotherapy, and most psychiatrists in managed care and publicly funded health care settings have stopped providing long-term psychotherapy to a small number of patients. Instead, they have a consultant-based clinical role similar to that of other specialists. In the United Kingdom, psychiatrists have the role of consultants mandated to manage the most complex psychiatric cases, ideally within a multidisciplinary team23,24; the services of psychologists and other mental health workers are covered by public insurance, and these professionals provide evidence-based psychotherapy at a lower hourly rate than the psychiatrists' consultation rate. In 2006, psychologists, occupational therapists, and social workers were incorporated into the Australia fee schedule to provide psychotherapy and focused psychological strategies, but they are paid at lower rates than psychiatrist consultation reimbursement.25 Creating a differential between the relatively high reimbursement for consultations and the relatively low reimbursement for psychotherapy has led to reductions in visit frequency, which suggests that financial incentives were effective in changing psychiatrists' practice patterns.26 In the United States, health maintenance organizations have created mental health "carve-outs," in which psychologists and other allied mental health professionals provide psychotherapy at lower rates, whereas within US Medicaid and Medicare, psychiatrists are paid an hourly fee that is more than twice as high for pharmacotherapy and psychiatric consultations as for psychotherapy.27

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate psychiatrists' practice patterns in regions of differing supply in a universal health care setting. It was a population-based study, evaluating the provision of psychiatric services to more than 13 million residents representing more than one-third of the Canadian population. The study had several limitations. First, we identified full-time psychiatrists on the basis of their billings. Although about 94% of Ontario physicians have a fee-for-service practice,28 a small proportion of psychiatrists receive a salary. These salaried physicians are asked to "shadow bill" for their services, but because their earnings are not tied to the shadow billing, their clinical activity may be underreported. As a result, some of these salaried full-time psychiatrists may have been excluded from our analysis. This possibility is unlikely to have biased the study results, since the patient panels of these salaried psychiatrists should be similar to the panels of those who were included. The South East LHIN is a relatively small LHIN that had proportionally more physicians who were not captured in the OHIP database; however, the characteristics of their patient panels followed the general gradients with supply. Also, most salaried psychiatrists work within Assertive Community Treatment multidisciplinary teams, which are designed to provide treatment to individuals with severe and persistent mental illness. Because there are few such psychiatrists and they do not practise in specific regions, they could not account for the variations observed in this study. Second, we ascertained clinical severity solely on the basis of prior psychiatric hospital admissions; however, this measure was sufficiently sensitive to detect significant variations across visit frequency categories. Third, the 5 individual LHINs used for our analyses were chosen because they each had a large supply of psychiatrists and because they were large urban centres with medical schools where psychiatry residents train. Thus, the presence of a medical school and its residents cannot explain the differences in practice gradients between high-supply and low-supply LHINs. Fourth, we did not differentiate between generalist and subspecialist psychiatrists. Both schizophrenia specialists and general psychiatrists are able to provide consultations or care following a hospital admission for schizophrenia. Although there are likely more subspecialist psychiatrists in urban settings, this cannot explain our findings: there is no reason that full-time subspecialists would have dramatically smaller panels of patients whom they saw more frequently than did generalists; in fact, we would expect the opposite, since subspecialists would be less likely to provide psychotherapy.

Conclusion.

Our study confirms, for psychiatric care in Ontario, a strong relationship between supply and utilization but a mismatch between supply and population need. Our results raise fundamental questions about psychiatrists' scope of practice and how these physicians should be incentivized to meet the population's mental health needs. The typical response to poor access to physicians is to conclude that more physicians are needed. If the patterns seen in this study persist, increasing psychiatrist supply will have little impact on patients' access to essential services. Our findings suggest that addressing the fee schedule and the lack of criteria constraining the frequency of, duration of, and indications for psychotherapy may be required to increase access to psychiatrists. They also suggest that how psychiatrists are financially reimbursed and, consequently, how and where they practice, are more important factors than head counts when evaluating whether more psychiatrists are needed to improve access to care.

Footnotes

None declared.

Funding for this study was provided by an Emerging Team Grant (ETG92248) in Applied Health Services and Policy Research from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Dr. Kurdyak is supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Contributor Information

Paul Kurdyak, Paul Kurdyak, MD, PhD, is Director of Health Systems Research in the Social and Epidemiological Research Program at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Lead of the Mental Health and Addictions Research Program at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario..

Thérèse A Stukel, Thérèse A. Stukel, PhD, is a Senior Scientist at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto, Ontario; Professor at the Institute for Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario; and an Adjunct Professor at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Giesel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire..

David Goldbloom, David Goldbloom, MD, is the Senior Medical Advisor at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and a Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario. He is also Chair of the Mental Health Commission of Canada..

Alexander Kopp, Alexander Kopp, MSc, is the Lead Analyst in the Primary Care and Population Health Program at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto, Ontario..

Brandon M Zagorski, Brandon M. Zagorski, MSc, is an Analyst at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto, Ontario..

Benoit H Mulsant, Benoit H. Mulsant, MD, MS, is Physician-in-Chief at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and is Professor and Vice-Chair in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario..

References

- 1.Freeman Cook A, Hoas H. Hide and seek: the elusive rural psychiatrist. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31(6):419–422. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.31.6.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudson N. Geographic variation in alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health services utilization: what is the role of physician practice patterns? Find Brief. 2007;10(7):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, Yu BN, Stein MB. Mental health service use in a nationally representative Canadian survey. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(12):753–761. doi: 10.1177/070674370505001204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilk JE, West JC, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Regier DA. Access to psychiatrists in the public sector and in managed health plans. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(4):408–410. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.4.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham PJ. Beyond parity: primary care physicians' perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):w490–w501. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Physician Survey: 2010 national results by FP/GP or other specialist, sex, age, and all physicians. Mississauga (ON): National Physician Survey; 2010. Section D: Patient access to care. Available from: www.nationalphysiciansurvey.ca/nps/2010_Survey/Results/physician1-e.asp (accessed 2011 Aug 25). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldner EM, Jones W, Fang ML. Access to and waiting time for psychiatrist services in a Canadian urban area: a study in real time. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(8):474–480. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176–181. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sargeant JK, Adey T, McGregor F, Pearce P, Quinn D, Milev R, et al. Psychiatric human resources planning in Canada [position paper, Canadian Psychiatric Association] Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(9):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Supply, distribution and migration of Canadian physicians, 2011. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The 2012 statistical abstract. The national data book: Health and nutrition. Washington (DC): United States Census Bureau; 2012. Table 164: Physicians by sex and specialty: 1980 to 2009. Available from: www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/health_nutrition.html (accessed 2012 Feb 28). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eveland AP, Dever GE, Schafer E, Sprinkel C, Davis S, Rumpf M. Analysis of health service areas: another piece of the psychiatric workforce puzzle. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(7):956–960. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.7.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufmann IM. Rural psychiatric services. A collaborative model. Can Fam Physician. 1993;39:1957–1961. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nugent K. Shortage of psychiatrists plaguing northern Ontario. CMAJ. 1992;147(6):847–847. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Exploring hospital mental health service use in Ontario, 2007-2008. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2009. 18 pp. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/OMHRS_aib_en.pdf (accessed 2014 May 30). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quality monitor: 2012 report on Ontario's health system. Toronto (ON): Health Quality Ontario; 2012. pp. 72–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Druss BG, Miller CL, Pincus HA, Shih S. The volume-quality relationship of mental health care: does practice make perfect? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2282–2286. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Full-time equivalent (FTE) physicians report, fee-for-service physicians in Canada, 2004-2005. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2006. 66 pp. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productSeries.htm?pc=PCC37 (accessed 2014 May 30). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steele LS, Glazier RH, Agha M, Moineddin R. The gatekeeper system and disparities in use of psychiatric care by neighbourhood education level: results of a nine-year cohort study in Toronto. Healthc Policy. 2009;4(4):e133–e150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steele LS, Glazier RH, Lin E. Inequity in mental health care under Canadian universal health coverage. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):317–324. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olah ME, Gaisano G, Hwang SW. The effect of socioeconomic status on access to primary care: an audit study. CMAJ. 2013;185(6):E263–E269. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hope R. New ways of working in mental health for everyone. London (UK): National Institute for Mental Health England; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Role of the consultant psychiatrist. Leadership and excellence in mental health services. Occas Pap OP74. London (UK): Royal Society of Psychiatrists; 2010. Available from www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/op74.pdf (accessed 2011 Jun 13). [Google Scholar]

- 25.National action plan on mental health 2006–2011. Canberra (Australia): Council of Australian Governments; 2006. 41 pp. Available from: www.coag.gov.au/sites/default/files/NAP%20on%20Mental%20Health%20-%20Fourth%20Progress%20Report.pdf (accessed 2014 May 30). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doessel DP, Scheurer RW, Chant DC, Whiteford H. Financial incentives and psychiatric services in Australia: an empirical analysis of three policy changes. Health Econ Policy Law. 2007;2(Pt 1):7–22. doi: 10.1017/S1744133106006244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barlas S. Unfavorable changes to medicare loom for psychiatrists. Psychiatr Times. 2012. Jan 04, Available from: www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/unfavorable-changes-medicare-pay-loompsychiatrists (accessed 2014 Jun 8). Registration required to access content.

- 28.Wang L, Jason XN, Upshur REG. Determining use of preventive health care in Ontario: comparison of 3 maneuvers in administrative and survey data. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(2):178–179. e5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]